Digital Financial Inclusion to Corporation Value: The Mediating Effect of Ambidextrous Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Assumptions

2.1. Development of DFI and Corporation Value

2.2. Ambidextrous Innovation and Corporation Value

2.3. DFI and Ambidextrous Innovation

2.4. The Mediating Role of Ambidextrous Innovation

2.5. The Moderating Effect of Financial Flexibility

2.6. The Moderating Role of CSR

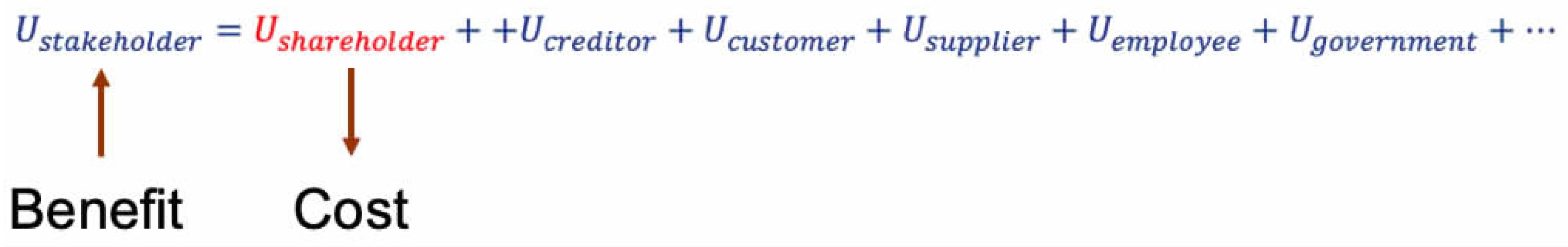

2.7. The Regulatory Role of Product Market Competition

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Model Setting and Variable Definition

3.3. Descriptive Analyses

4. Empirical Test and Results Analysis

4.1. Test of the Impact of DFI on Corporation Value

4.2. Test in the Mediating Role of Ambidextrous Innovation

4.3. Test of the Regulatory Role in Financial Flexibility and CSR

4.4. Test of the Regulatory Role of Product Market Competition

4.5. Robustness Test

4.5.1. Replacement of Key Variables

4.5.2. Endogeneity

5. Conclusions and Discussion

- (1)

- DFI has a significant positive impact on corporation value and ambidextrous innovation. Present researchers believe that DFI can promote corporate innovation, but have not explored the differences in the impact of DFI on different innovation methods. It has been found that DFI plays a significant role in promoting exploitative innovation, but there is a time lag in the role of exploratory innovation, and its promoting effect on exploratory innovation is weaker than that on exploitative innovation.

- (2)

- By examining the mediation effect test, we find that ambidextrous innovation partially mediates the relationship between DFI and corporation value; that is, DFI promotes the development of corporation value by affecting the ambidextrous innovation.

- (3)

- Inside of the enterprise, financial flexibility positively moderates the relationship between DFI and exploitative innovation. In the external environment of the corporation, CSR negatively moderates the relationship between digital inclusive finance and corporate value in the short term. However, in the long term, it does contribute to the growth of corporate value. This indicates that corporations need to strengthen financial flexibility internally, and improve CSR externally, in order to leverage DFI to create and deliver corporation value.

- (4)

- The more intense PMC is, the stronger the ability of enterprises to promote exploitative innovation through DFI becomes. However, product market competition does not have a significant impact on DFI with regard to exploratory innovation, because exploratory innovation will lead to more serious information asymmetry compared with exploitative innovation, which requires higher financing constraints and adjustment costs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gabor, D.; Brooks, S. The digital revolution in financial inclusion: International development in the fintech era. New Political Econ. 2017, 22, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. Digital Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Growth of Small and Micro Enterprises—Evidence Based on China’s New Third Board Market Listed Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, K.; Xu, H. Has digital financial inclusion narrowed the urban-rural income gap: The role of entrepreneurship in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, G. Digital Financial Inclusion and Farmers’ Vulnerability to Poverty: Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhao, C. Poverty reduction in rural China: Does the digital finance matter? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pana, E.; Vitzthum, S.; Willis, D. The impact of internet-based services on credit unions: A propensity score matching approach. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2015, 44, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2018, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtiani, J.; Lemieux, C. Do fintech lenders penetrate areas that are underserved by traditional banks ? J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 100, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-H.; Tian, X.; Xu, Y. Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence. J. Financial Econ. 2014, 112, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.P.; Arvin, M.B.; Hall, J.H.; Nair, M. Innovation, financial development and economic growth in Eurozone countries. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2016, 23, 1141–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kumara, E.K.; Sivakumar, V. Invesitigation of finance industry on risk awareness model and digital economic growth. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, H. Proposals for a Digital Industrial Policy for Europe. Telecommun. Policy 2019, 43, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demertzis, M.; Merler, S.; Wolff, G.B. Capital Markets Union and the fintech opportunity. J. Financ. Regul. 2018, 4, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, A.; PLoSser, M.; Schnabl, P.; Vickery, J. The Role of Technology in Mortgage Lending. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1854–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Peria, M.S.M. Reaching out: Access to and use of banking services across countries. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 85, 234–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, I.; Pería MS, M. How Bank Competition Affects Firms’ Access to Finance. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2015, 29, 413–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Li, H.; Li, S. Corporate social responsibility and stock price crash risk. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomber, P.; Kauffman, R.J.; Parker, C.; Weber, B.W. On the fintech revolution: Interpreting the forces of innovation, disruption, and transformation in financial services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 220–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallee, B.; Zeng, Y. Marketplace lending: A new banking paradigm? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1939–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, I.J.; van Ewijk, S.E. Can pure play internet banking survive the credit crisis? J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, R.N.; Kagan, A. Community banks and internet commerce. J. Internet Commer. 2004, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xin, Y.; Luo, Z.; Han, M. The Impact of Stable Customer Relationships on Enterprises’ Technological Innovation Based on the Mediating Effect of the Competitive Advantage of Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R. Understanding competence-based management: Identifying and managing five modes of competence. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.V. Performance, Slack, and Risk Taking in Organizational Decision Making. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisbe, J.; Malagueño, R. Using strategic performance measurement systems for strategy formulation: Does it work in dynamic environments? Manag. Account. Res. 2012, 23, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.; Burg, V.; Gombović, A.; Puri, M. On the rise of fintechs: Credit scoring using digital footprints. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 2845–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, M.T.; Garfinkel, J.A. Financial Flexibility and the Cost of External Finance for U.S. Bank Holding Companies. J. Money Credit. Bank. 2004, 36, 827–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, A.; Triantis, A. The Value of Financial Flexibility. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 2263–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, M.S.; Schmid, T.; Urban, D. The value of financial flexibility and corporate financial policy. J. Corp. Finan. 2014, 29, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, C.J.; Pierce, J.R. New Evidence on Measuring Financial Constraints: Moving Beyond the KZ Index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Li, O.Z.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. Digital finance, technology innovation, and marine ecological efficiency. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 108, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, M.J.; Tushman, M.L. Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G. Exploratory Learning, Innovative Capacity and Managerial Oversight. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Jones, R.J., III. Entrepreneurial Exploration and Exploitation in Family Business: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 29, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Masron, T.A. Impact of Digital Finance on Energy Efficiency in the Context of Green Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippmann, E.; Scott, P.S.; Mangematin, V. Stimulating knowledge search routines and architecture competences: The role of organizational context and middle management. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, P.; Maicas, J.P.; Vargas, P. Exploration, exploitation and innovation performance: Disentangling the evolution of industry. Ind. Innov. 2019, 26, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errays, N.A. Exploring how social capital facilitates innovation: A theoretical study through the role of personal network dynamics and organizational culture. Rev. Des Etudes Multidiscip. En Sci. Econ. Et Soc. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and Future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Lin, C.; Ma, H. Top management team diversity, ambidextrous innovation and the mediating effect of top team decision-making processes. Ind. Innov. 2016, 23, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraies, S.; Abidine, S.Z. Do leadership styles promote ambidextrous innovation? Case of knowledge-intensive firms. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 836–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Ma, L.; Feng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Z. Impact of Technology Habitual Domain on Ambidextrous Innovation: Case Study of a Chinese High-Tech Enterprise. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccieri, D.; Javalgi, R.G.; Cavusgil, E. International new venture performance: Role of international entrepreneurial culture, ambidextrous innovation, and dynamic marketing capabilities. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 01639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combe, I.A.; Rudd, J.M.; Leeflang, P.S.; Greenley, G.E. Antecedents of strategic flexibility: Management cognition, firm resources and strategic options. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1320–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F.; Miller, M.H. The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance, and the Theory of Investment: Reply. Am. Econ. Rev. 1959, 49, 655–669. [Google Scholar]

- Eckel, C.; Neary, J.P. Multi-Product Firms and Flexible Manufacturing in the Global Economy. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2010, 77, 188–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wong, P.K. Exploration vs. Exploitation: An Empirical Test of the Ambidexterity Hypothesis. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Shin, Y.J. Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. The role of R&D and input trade in productivity growth: Innovation and technology spillovers. J. Technol. Transf. 2020, 45, 908–928. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, A.J.; Welker, M. Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital. Account. Organ. Soc. 2001, 26, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, H.; DeAngelo, L.E. Capital Structure, Payout Policy, and Financial Flexibility. 2007. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=916093 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Graham, J.R.; Harvey, C.R. The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. J. Financ. Econ. 2001, 60, 187–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, T. The dangers of social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1958, 36, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.; Walker, M.; Zeng, C. Do Chinese state subsidies affect voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosure? J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A. Corporate social responsibility and corporate cash holdings. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 37, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.A.; Romi, A.M.; Sánchez, D.; Sanchez, J.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility on investment efficiency and innovation. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2019, 46, 494–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance: The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility during the Financial Crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wartick, S.L.; Cochran, P.L. The Evolution of the Corporate Social Performance Model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Liang, B. Competition and Heterogeneous Innovation Qualities: Evidence from a Natural Experiment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderton, R.M.; Lupidio, B.D.; Jarmulska, B. The impact of product market regulation on productivity through firm churning: Evidence from European countries. Econ. Model. 2020, 91, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cao, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Knowledge Power on Enterprise Breakthrough Innovation: From the Perspective of Boundary-Spanning Dual Search. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Leker, J. Exploration and exploitation in product and process innovation in the chemical industry. R&D Manag. 2013, 43, 196–212. [Google Scholar]

- Popadić, M.; Černe, M. Exploratory and exploitative innovation: The moderating role of partner geographic diversity. Econ. Res. -Ekon. Istraživanja 2016, 29, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConaughy, D.L.; Walker, M.C.; Henderson, G.V., Jr.; Mishra, C.S. Founding family controlled firms: Efficiency and value. Rev. Financ. Econ. 1998, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Kim, S.; Cho, M.-K. The Effect of R&D and the Control–Ownership Wedge on Firm Value: Evidence from Korean Chaebol Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2986. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Ma, F.; Deng, W.; Pi, Y. Digital inclusive finance and rural household subsistence consumption in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tang, X. The impact of digital inclusive finance on sustainable economic growth in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wang, F. How does inclusive finance affect carbon intensity? Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 75, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Long, H.; Ouyang, J. Digital Financial Inclusion, Spatial Spillover, and Household Consumption: Evidence from China. Complex 2022, 2022, 8240806:1–8240806:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chi, G.-D.; Han, L. Board Human Capital and Enterprise Growth: A Perspective of Ambidextrous Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, B.; Ye, J.; Feng, Y.; Cai, Z. Explicit and tacit synergies between alliance firms and radical innovation: The moderating roles of interfirm technological diversity and environmental technological dynamism. R&D Manag. 2020, 50, 432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Peress, J. Product Market Competition, Insider Trading, and Stock Market Efficiency. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, J.R.; Loon, Y.C. Product market power and stock market liquidity. J. Financ. Mark. 2011, 14, 376–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Business model innovation, legitimacy and performance: Social enterprises in China. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2693–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B.J. Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chun, D. The Influencing Mechanism of Internal Control Effectiveness on Technological Innovation: CSR as a Mediator. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourné, S.P.; Rosenbusch, N.; Heyden, M.L.; Jansen, J.J. Structural and contextual approaches to ambidexterity: A meta-analysis of organizational and environmental contingencies. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryak, O.; Lockett, A.; Hayton, J.; Nicolaou, N.; Mole, K. Disentangling the antecedents of ambidexterity: Exploration and exploitation. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governanc; Zimmerli, W.C., Holzinger, M., Richter, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Manchiraju, H.; Rajgopal, S. Does corporate social responsibility (CSR) create shareholder value? Evidence from the Indian Companies Act 2013. J. Account. Res. 2017, 55, 1257–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J. Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Duan, K. Substantive innovation or strategic innovation? Research on multiplayer stochastic evolutionary game model and simulation. Complexity 2020, 2020, 9640412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, J. Research on a Compound Dual Innovation Capability Model of Intelligent Manufacturing Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Acronyms | Calculation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate value | TobinsQ | TobinsQ = (Equity Market Value + Net debt market value)/Total assets at period end | McConaughy et al. (1998) [68]; Kang et al. (2019) [69]; |

| Digital finance inclusive | DFI | The Peking University Digital Financial Inclusion Index of China (PKU-DFIIC) | Yang and Zhang (2020) [2]; Yang et al. (2022) [70]; Sun and Tang (2022) [71]; Lee and Wang (2022) [72]; Li et al. (2022) [73] |

| Exploitative innovation | Incremental | Capitalized expenditure on R&D investments/Operating revenue | Kang et al. (2019) [69]; Liu and Han (2019) [74] |

| Exploratory innovation | Radical | Expensed expenditure on R&D investments/Operating revenue | |

| Financial flexibility | FF | Financial Flexibility = (Corporate cash holding ratio-Industry average cash holding ratio) +Max (Industry average gearing ratio-Corporate gearing ratio, 0) | DeAngelo, H., and DeAngelo, L.E. (2007) [53] |

| Corporate social responsibility | CSR | Hexun Social Responsibility Report Professional Review | Wang et al. (2021) [75] |

| Product market competition | PMC | Product market competition = (Total profit + total tax + total interest)/Average total assets | Peress J. (2010) [76]; Kale and Loon (2010) [77]; Wang and Zhou (2020) [78] |

| Enterprise size | Size | Ln (Assets at end of period + 1) | Chen et al. (2021) [22] |

| Enterprise age | Age | Year of statistics–Year of Establishment | Li et al. (2016) [41] |

| Enterprise growth | Gro | (Total operating income for the period–Total operating income for the previous period)/Total operating income for the previous period | Cheung (2016) [57] |

| Leverage | Lev | Total liabilities/Total Assets | Dhaliwal et al. (2011) [31] |

| Cash ratio | CR | Cash and cash equivalents/Current liabilities | Yang and Zhang (2020) [2] |

| Size of board of directors | Bod | Number of Board of Directors | Chen et al. (2021) [22] |

| Industry | Industry | Industry dummy variable | |

| Year | Year | Year dummy variable |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TobinsQ | 1.412 | 1.535 | 0.811 | 6.542 |

| DFI | 291.062 | 80.672 | 75.870 | 431.928 |

| Incremental | 0.124 | 1.485 | 0.000 | 4.865 |

| Radical | 0.076 | 1.504 | 0.015 | 1.000 |

| FF | 0.124 | 0.215 | −0.279 | 0.982 |

| CSR | 20.675 | 10.767 | −18.450 | 85.240 |

| PMC | 0.158 | 0.179 | −2.910 | 4.730 |

| Size | 21.400 | 0.838 | 19.290 | 25.777 |

| Age | 15.484 | 4.886 | 3.000 | 25.000 |

| Gro | 0.505 | 0.365 | −0.683 | 1.294 |

| Lev | 0.315 | 0.183 | 0.011 | 1.687 |

| CR | 1.589 | 3.641 | 0.001 | 2.931 |

| Bod | 7.944 | 1.432 | 4.000 | 15.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | TobinsQ | Incremental (1 Period Lagged) | Radical (1 Period Lagged) | VIF | Radical (2 Period Lagged) | ||

| DFI | 0.005 ** | 0.614 * | 0.242 | 1.260 | 0.360 *** | ||

| (0.002) | (0.338) | (0.235) | (0.134) | ||||

| Incremental | 2.997 ** | ||||||

| (1.382) | |||||||

| Radical | |||||||

| (1.429) | |||||||

| −0.250 *** | −0.173 ** | −0.968 *** | 28.658 *** | −9.271 ** | 1.160 | −5.174 | |

| (0.072) | (0.072) | (0.091) | (9.334) | (3.639) | (4.531) | ||

| Age | −0.111 | 0.021 | −0.064 *** | −23.919 ** | −9.715 ** | 1.390 | −8.871 ** |

| (0.072) | (0.016) | (0.021) | (10.041) | (4.014) | (4.499) | ||

| Gro | 0.094 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.251 *** | 4.532 | −0.002 | 1.050 | −0.648 |

| (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.057) | (2.916) | (0.058) | (1.382) | ||

| Bod | −0.036 | −0.054 * | −0.044 | 6.988 * | −4.373 ** | 1.120 | −4.166 ** |

| (0.033) | (0.032) | (0.040) | (4.246) | (1.700) | (1.927) | ||

| CR | −0.064 *** | −0.067 *** | −0.062 *** | 4.392 *** | 0.348 | 1.320 | 0.613 |

| (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (1.196) | (0.398) | (0.414) | ||

| Lev | −0.798 *** | −0.447 | −0.222 | 11.053 | 4.113 | 1.180 | 20.125 |

| (0.289) | (0.284) | (0.351) | (36.756) | (14.928) | (17.711) | ||

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Constant | 9.007 *** | 6.755 *** | 25.387 *** | −426.167 ** | 213.778 *** | 232.461 *** | |

| (1.453) | (1.364) | (1.718) | (185.069) | (73.476) | (85.584) | ||

| (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | TobinsQ | |

| Incremental/Radical | 0.001 ** | 0.000 ** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| DFI | 0.016 *** | 0.013 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| L.Size | −0.741 *** | −0.733 *** |

| (0.086) | (0.085) | |

| L.Age | 0.448 *** | −0.400 *** |

| (0.089) | (0.089) | |

| L.Gro | 0.083 *** | 0.053 ** |

| (0.027) | (0.026) | |

| L.Lev | −0.030 | −0.021 |

| (0.038) | (0.037) | |

| L.CR | 0.482 | 0.590 * |

| (0.336) | (0.333) | |

| Industry | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 16.676 *** | 21.147 *** |

| (1.699) | (1.673) | |

| Sobel | α1, β1,1 and γ1,1 are significantly | Z = 2.779 > 0.97 |

| (8) | (9) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | TobinsQ | TobinsQ (1 Period Lagged) | |

| DFI | 0.001 * | 0.003 *** | 0.002 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| CSR | −0.029 *** | 0.026 *** | |

| (0.010) | (0.004) | ||

| CSR×DFI | −0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| FF | 3.899 *** | ||

| (0.607) | |||

| FF×DFI | 0.015 *** | ||

| (0.002) | |||

| Size | −0.528 *** | −0.673 *** | −0.746 *** |

| (0.047) | (0.046) | (0.051) | |

| Age | −0.029 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.016 * |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Gro | 0.065 ** | 0.067 ** | 0.044 |

| (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.031) | |

| Bod | −0.053 ** | −0.063 *** | −0.079 *** |

| (0.025) | (0.024) | (0.026) | |

| CR | −1.918 *** | −1.426 *** | −1.008 *** |

| (0.288) | (0.232) | (0.257) | |

| Lev | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.040 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 16.405 *** | 19.184 *** | 20.075 *** |

| (0.966) | (0.959) | (1.047) | |

| (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Incremental | Radical | Incremental | Radical |

| DFI | 1.595 *** | 0.249 ** | 1.577 *** | 0.189 * |

| (0.273) | (0.113) | (0.273) | (0.115) | |

| PMC | 148.134 *** | −51.802 | 125.303 *** | 96.628 *** |

| (27.865) | (48.969) | (28.556) | (32.965) | |

| PMC×DFI | 46.278 *** | 0.328 *** | ||

| (8.981) | (0.101) | |||

| Size | −40.328 *** | −11.040 *** | −52.984 *** | −10.180 *** |

| (8.863) | (3.598) | (8.450) | (3.605) | |

| Age | −51.599 *** | 9.504 *** | −20.044 *** | 9.060 *** |

| (8.452) | (3.503) | (5.686) | (3.503) | |

| Gro | 5.050 * | 0.478 | 3.410 | 0.134 |

| (2.854) | (1.167) | (3.907) | (0.902) | |

| Bod | 3.078 | 3.164 ** | −25.567 | 3.154 * |

| (3.910) | (1.611) | (34.854) | (1.609) | |

| CR | −36.452 | 14.081 | −0.537 | 6.776 |

| (34.800) | (14.163) | (1.014) | (14.322) | |

| Lev | −0.042 | −0.026 | 1.577 *** | −0.108 |

| (1.010) | (0.420) | (0.273) | (0.420) | |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −434.489 ** | 256.031 *** | −536.664 *** | 0.122 |

| (176.928) | (71.987) | (178.713) | (0.434) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ROE | ROE | ROE | D | R | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE (1 Period Lagged |

| D | 0.210 ** | 0.002 ** | ||||||||

| (0.032) | (0.001) | |||||||||

| R | 0.002 ** | |||||||||

| 0.102 *** | (0.001) | |||||||||

| DFI | 0.000 * | (0.001) | 0.014 ** | 0.024 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.001 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 ** | |

| (0.000) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |||

| CSR | −0.017 *** | 0.015 *** | ||||||||

| (0.003) | (0.001) | |||||||||

| CSR×DFI | 0.000 *** | 0.000 * | ||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||||

| FF | 0.105 *** | |||||||||

| (0.009) | ||||||||||

| FF×DFI | 0.002 *** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | ||||||||||

| Size | 0.078 *** | −0.004 | −0.298 *** | 0.094 | 0.009 | −0.305 *** | −0.305 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.046 *** | 0.036 * |

| (0.013) | (0.005) | (0.029) | (0.517) | (0.492) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.020) | |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.028 | −0.016 *** | −0.021 | 0.056 | −0.016 *** | −0.016 *** | −0.000 | −0.000 | 0.001 |

| (0.002) | (0.020) | (0.005) | (0.086) | (0.082) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Gro | 0.026 *** | 0.051 *** | −0.002 | −0.083 | −0.271 | 0.032 ** | 0.032 ** | 0.025 *** | 0.020 ** | −0.003 |

| (0.007) | (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.279) | (0.309) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.012) | |

| Bod | 0.004 | 0.016 ** | −0.020 | 0.136 | 0.093 | −0.017 | −0.017 | −0.000 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.015) | (0.270) | (0.257) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.010) | |

| CR | 0.012 *** | 1.378 *** | 0.004 | 0.064 | −0.001 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.010 *** | −0.010 *** | 0.001 |

| (0.003) | (0.155) | (0.007) | (0.116) | (0.111) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Lev | −1.077 *** | −0.003 *** | −1.384 *** | 0.644 | −4.383 * | −1.374 *** | −1.383 *** | −0.841 *** | −0.770 *** | 0.076 |

| (0.064) | (0.001) | (0.141) | (2.509) | (2.385) | (0.141) | (0.141) | (0.066) | (0.066) | (0.099) | |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −1.240 *** | 6.820 *** | 8.652 *** | 5.011 | 2.123 | 8.205 *** | 8.209 *** | −0.748 *** | −0.294 | 0.719 |

| (0.270) | (0.652) | (0.605) | (10.514) | (10.003) | (0.634) | (0.634) | (0.269) | (0.292) | (0.445) | |

| Phase I Returns | Phase II Returns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DFI | DFI | ROE | ROE |

| distance | −0.018 *** | −0.019 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| DFI | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| Age | 3.811 *** | −0.305 *** | ||

| (0.543) | (0.029) | |||

| Gro | 0.166 * | −0.016 *** | ||

| (0.091) | (0.005) | |||

| Bod | −0.348 | 0.032 ** | ||

| (0.291) | (0.016) | |||

| Size | −1.531 *** | −0.017 | ||

| (0.279) | (0.015) | |||

| CR | 0.259 ** | 0.004 | ||

| (0.120) | (0.007) | |||

| Lev | −7.121 *** | −1.383 *** | ||

| (2.634) | (0.141) | |||

| Constant | 3.049 *** | 2.354 *** | 0.953 *** | 8.214 *** |

| (0.097) | (0.285) | (0.218) | (0.634) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Shi, S.; Wu, J. Digital Financial Inclusion to Corporation Value: The Mediating Effect of Ambidextrous Innovation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416621

Yang Y, Shi S, Wu J. Digital Financial Inclusion to Corporation Value: The Mediating Effect of Ambidextrous Innovation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416621

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yi, Shuhe Shi, and Jingjing Wu. 2022. "Digital Financial Inclusion to Corporation Value: The Mediating Effect of Ambidextrous Innovation" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416621

APA StyleYang, Y., Shi, S., & Wu, J. (2022). Digital Financial Inclusion to Corporation Value: The Mediating Effect of Ambidextrous Innovation. Sustainability, 14(24), 16621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416621