Abstract

Servant leadership is a style that is considered to be ethical, positive, and desirable due to its compatibility with an array of situations. Moreover, work engagement is a key factor that can have positive short- and long-term outcomes for organizations. This research focuses on the role of servant leaders and their effects on employees’ work engagement in an academic setting. Furthermore, the role of trust as a mediator is analyzed to shed light upon its effect after the pandemic of COVID-19. As the academic sector has faced an abrupt shift to online formats, this study emphasizes on the role of leaders in fostering wellbeing for academic staff. This research emphasizes trust and work engagement as important elements for achieving positive employee outcomes within the context of sustainable psychology as a scientific domain. Through a specified approach, a sample of 138 people was collected from various faculty members and analyzed by SmartPLS. Results suggest a strong role played by servant leaders in improving the work engagement of their staff. Similarly, the mediating role of trust in a leader is statistically significant, implying its vitality for improving work engagement in an academic setting. These results can be beneficial for researchers (leadership and organizational psychology) and practitioners in the education sector.

1. Introduction

Leadership is a source for organizations to maintain their competitive advantages [1,2], and its importance cannot be neglected, as leaders’ influence goes beyond their roles [3]. This steers firms towards taking actions that emphasize leadership practices, which are imperative for enhancing organizational outcomes [4]. Leaders can impact their followers’ behavior by establishing positive environments, in which individuals’ wellbeing and quality of life are focused upon. With the occurrence of the COVID-19 global pandemic, many organizations had to shift their work to digital platforms. This is especially vivid in the context of academia, which is the focus of this study. Various changes in this sector (e.g., shift from traditional classes to online), similar to other industries with high levels of demand and workload, had an explicit impact on employees’ wellbeing. As this research investigates the effects of leadership on employee outcomes, work engagement during online classes and/or meetings is specifically focused upon. Work engagement has been linked to a number of employee outcomes, such as commitment, turnover intentions, wellbeing, extra-role behavior, and performance [2,5,6,7,8,9]. In this study, it is conceptualized that enhancing the work environment (i.e., academic setting) through trust-building can yield an overarching improvement of the psychological state of individuals in the workplace. This falls within the concept of sustainable psychology (i.e., long lasting effects). In other words, through adequate leadership styles, a long-term positive effect can be achieved in the behavior of academic staff as trust strengthens, and the overall wellbeing of employees are emphasized by the leader.

This research focuses on servant leadership, in which progress, wellbeing, and the values of followers are emphasized [10,11,12]. Servant leaders distinguish themselves from traditional leaders by focusing on serving others first. This establishes a notion of trust for employees, as servant leaders tend to followers individually and create personal bonds that go beyond the norms and boundaries of work [3]. It has been noted that servant leadership is a driver and nexus for positive work outcomes due to its characteristics. An effective leader is able to influence his/her followers not merely through work conditions, but also through inspiration, connection, empowerment, and trust. This has been reported by a number of studies conducted using various methods, which show a consensus among scholars, e.g., [2,12,13,14].

Servant leadership is considered as an ethical form of leader behavior with abilities that are suitable and adequate for times of crisis and chaos [3]. The current research builds on the recent findings in regards to servant leadership literature and aims to contribute to its understanding. In a recent study conducted by [2], it was noted that the context of leadership and work engagement require further research. In particular, servant leadership was only mentioned in their research, and an examination of positive leadership behaviors is recommended. The leader-and-follower relationship has outcomes that affect the work–life balance and overall quality of life of individuals [15]. This becomes more significant for employees, and vital during times of crisis. Therefore, this research focuses on servant leaders, who put the interest of their employees before their own, which can yield in positive work outcomes (i.e., work engagement) through an emphasis on building trust [3,12,16,17]. Accordingly, this study aims to contribute to the extant literature and, thus, it aims to yield in beneficial results for scholars and organizations alike. Organizational psychology, leadership, and organizational behavior after COVID-19 are among the subjects addressed by this research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Servant Leadership and Work Engagement

Considering this leadership style was developed decades ago (1970s), it has been reported that servant leadership requires further research and examination [12,18]. Servant leaders, by essence, aim to benefit and improve others, going beyond their followers, and reaching society at large [10]. This definition has been the main source of the theoretical development of servant leadership. It is important to note that chaos theory can adequately explain servant leadership and its effectiveness. Decentralization, differentiation of tasks, collaboration, flexibility and adaptability of structures and processes, participation, and autonomy are among the key aspects that have been mentioned as linkages between the two concepts [19]. Accordingly, characteristics of servant leaders can be explained through chaos theory [3], which appropriately contextualizes this style of leadership in this study, which regards effective leaders during crisis and chaotic times (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic). Servant leaders can trigger employees’ work engagement to maintain a climate of work that benefits the overall wellbeing of academic staff, while enhancing the work environment. Notably, this is regarded as a concept within sustainable psychology in a manner that can positively impact employee outcomes over the long term. In this study, sustainable psychology is contextualized as a domain of organizational psychology that addresses the lasting impacts, influences, and results of employees’ behavior in the education sector. As the aim is to understand the role of leaders on positive employee outcomes (i.e., work engagement), it can be argued that engaging employees in the academic sector can have a positive influence on the environment of the workplace, which is beneficial for the organization, the students, and the academic staff. The current study focuses on the academic staff, as the employees in this section play important roles in the society. as they provide and/or enable learning for the future generations.

Characteristics of servant leaders enable them to create personal and meaningful bonds with their followers; namely, altruistic calling, wisdom, persuasive mapping, emotional leadership, and organizational stewardship [20]. Accordingly, they have the ability to reshape strategies and systems to enhance progress [3,21]. Furthermore, a servant leader creates an atmosphere of growth for their followers, which is highly relevant and vital in the context of this study, as the academic industry requires development in a constant manner [22]. Provision of tailored assistance in times of need, learning practices, and taking responsibility are among the roles that servant leaders carry out. The flexibility and nurturing capabilities of servant leaders are derived from their characteristics and approach, as noted earlier. These elements significantly impact the work environment and employees’ emotional and behavioral outcomes, which affects their overall wellbeing and quality of life [5,23,24]. The altruism of servant leaders enables them to maintain their focus on the values of their followers as a priority. This leads to a variety of positive outcomes, such as work engagement, trust, commitment, loyalty, extra-role behavior, job satisfaction, performance, service quality, and more [4,11,12,25].

Social Learning Theory [26] states that the learning process among humans occurs through observation and imitation. In other words, employees view their leader as a role-model and thus, positive behavioral patterns can be set by servant leaders to affect organizational culture and climate [18]. Similarly, Social Identity Theory [27], explains the manner by which employees can adopt the values of their firms through a sense of identification encouraged by their leader and/or peers. This ensures competitive advantages for the organization, as such, employees tend to exhibit higher performance and work engagement, and exhibit decreased turnover intentions [2,28,29]. Furthermore, this research entails Social Information Processing Theory [30], which includes a social behavior “cue” for employees by interacting with leader’s behavior (i.e., servant). This provides a vision for individuals to comprehend the desired organizational behavior. Building on the premise of the aforementioned theories, the current research shapes its direction by examining academic staff regarding the impacts of leadership (i.e., servant) on their behavior within the organization (i.e., work engagement). As servant leaders’ characteristics are embedded to trigger work engagement and build trust, it is expected that the positive approach of such leaders can enhance the work outcome of academic staff. Thus, this research assumes servant leaders’ means of conduct to be in accord with the noted theories and dimensions.

Work engagement is categorized into three distinct elements; namely vigor, which refers to high energy alongside resilience in mentality; dedication, which is explained as inspiration, pride, enthusiasm, and a feeling of uniqueness; and absorption, which is defined by willingness and happiness in conducting ones’ work [31,32,33]. In this sense, work engagement consists of physical, cognitive, and emotional components that translate into being involved (physically), vigil (cognitively), and engaged (emotionally) during working hours. This is crucial for academic staff (i.e., teachers), as their work engagement significantly affects the students’ learning and educational outcomes. Factors such as stress, anxiety, and loneliness can greatly impact teachers’ work engagement, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and during online classes [34]. This research focuses on the academic staff and their work engagement under the leadership of a servant leader, as it is imperative that academic staff are engaged with their work, as that influences the environment in which students are learning. Thus, the importance of tending to academic staff regarding their needs and wellbeing is vivid in the context of academia, as it encompasses future generations and societal outcomes [34]. Building on Self-Determination Theory [35], servant leaders are able to encourage work engagement, as they go beyond work-centered matters and address competence, connection, and autonomy in a genuine manner. Similarly, Social Exchange Theory evokes reciprocation, which is caused by the positive and influential behaviors of servant leaders. This can further provide an atmosphere that encourages work engagement by interaction, communication, bonding and concern for individuals’ wellbeing [6,7,36,37]. In this research, work engagement is considered as a positive outcome that has long-term effects for individuals. This, in turn, can yield in desirable outcomes for the organization.

Servant leaders can obtain positive organizational outcomes beyond mere functionality and/or performance, and improve the wellbeing of employees, particularly through work engagement [12,15]. Work engagement has been reported as a direct and significant outcome of servant leadership, as a relational-oriented leadership among positive leader behaviors [2]. In this sense, work engagement is comprised of three aspects; namely vigor, dedication, and absorption. These components describe behavioral, emotional and cognitive dimensions of work engagement that can be nurtured and fulfilled by leaders through going beyond solely work-related matters, thereby building trust-centered relationships with their followers [7,32,38]. Considering the characteristics of servant leaders, this research argues that specifically regarding working conditions during COVID-19 for academic staff, servant leaders can positively impact work engagement by focusing on enhancing the wellbeing of individuals through various initiatives to increase their work engagement and establish a positive work setting. Hence, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Servant leadership has a direct effect on work engagement of academic staff during online education in the time of pandemic.

2.2. Mediating Role of Trust

Following what was noted above, it is also important to highlight the fact that servant leaders are able to build trust as a result of their characteristics and behavior within the organization. Employees’ skills, knowledge, and inputs are acknowledged and sought after by servant leaders, which creates an environment where trust can be fostered [3]. As servant leaders follow ethical means of conduct and tend to the personal lives of their followers, they can initiate a mutual trust [16]. This can lead to work engagement being positively influenced, which is vital for the wellbeing of academic staff, as their work–life balance and work conditions have severely been affected by the pandemic. According to recent findings in the extant literature of leadership and work engagement, trust is an influential element that links a leader to their followers. The result is a manifestation of desirable personal and professional outcomes for employees [2,7,34,39]. A servant leader plays a mentor role to positively impact personal aspects of individuals’ lives.

In addition to what was mentioned above, a servant leader is able to establish learning processes for employees. This can include organizational, group, or personal development practices. This is due to the fact that servant leadership is employee-centered. Servant leaders establish friendship, collaboration, shared values, accountability, learning, integrity, and altruism, which nurture trust as a psychological factor [3]. As a positive form of leadership (e.g., transformational, ethical, and authentic), trust is emphasized as a core concept for an effective leader. Servant leaders enable trust-building through their approach and strategies in relation to their followers. This, in turn, leads to an environment of trust, in which employees can exhibit and engage in positive behaviors and be motivated to show engagement with their work [2,40,41,42]. Additionally, role modeling, encouraging self-determination, and positive social interactions can provide positive yields in work engagement, as noted in the previous section, and is embedded in the theories that are used for current arguments [43,44,45].

As trust is a complex matter by nature, a mixture of perceptions towards the leader, as well as the organization and its environment, are incorporated [46]. Embedded within the premise of Social Exchange Theory [47], servant leaders possess the tools to foster trust in a “high quality” level. The essence of servant leadership addresses provision of service to followers, which is a pillar for establishing trust [12,48]. While performance can be increased through trust, other elements that can be beneficial for both employees’ wellbeing and organizations’ objectives are also influenced. Individuals can show more work engagement as the element of trust is established. As a consequence, this can positively impact wellbeing and work–life balance [2,5,49,50]. This research emphasizes the importance of wellbeing-oriented initiatives that servant leaders can deploy via Human Resource Management (HRM) departments [51]. By increasing trust among the leaders, the staff, and the organization, psychological aspects can be positively affected (e.g., Based on what was mentioned, this research assumes a mediating effect posed on servant leadership–work engagement linkage by element of trust in the leader. Hence, the following hypothesis has emerged:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Trust in leaders can mediate the relationship between servant leadership and his/her academic staffs’ work engagement during COVID-19 online education.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Criteria and Approach

The current research undertakes a quantitative approach, in which a questionnaire survey is designed from valid and reliable measurements in the extant literature. To address the hypotheses of this study and obtain its aims, several university managers (located in Turkey) and faculty deans were contacted. This led to understanding whether servant leadership was present in the organization. In this sense, conversations with managers and online meetings with a select few staff implied whether the school/faculty qualified for the specifics of this research. From six different universities, three were not qualified, while one school was qualified, which, as pilot test data were selected from it, data were omitted from final analyses. The remaining two universities were used in the data collection procedure. To ensure the appropriateness of representatives of the academic staff population, only teachers, tutors, researchers, and professors were addressed. It is considered that based on the context of academic staff in university, the aforementioned groups are appropriate representatives of the population (i.e., academic staff including deans, managers, clerks, assistants). As the current research is limited in terms of scope (see limitations), criteria specific to the study were followed, as explained in the following section. Upon completion of this stage, the relevant authorities were informed regarding data collection and the necessary permissions were granted. The sensitive information of the organizations and participants (through emails and other negotiations) have been strictly changed and codified for data confidentiality. These considerations also address common method bias and are implemented to minimize it [52].

3.2. Sampling Procedure

The data for the current research were gathered through online surveys shared with the academic employees of two universities approved by the research criteria. Notably, several faculties were selected as the result of the abovementioned conversations. Respondents were asked about their daily routines, which is proximal separation, recommended by Jordan and Troth (2020). The data were collected after the pandemic was controlled, and lockdowns and other strict restrictions were lifted in Turkey (data were collected during October–November 2021). In addition, loneliness, stress, and anxiety have been mentioned in these conversations to account for their effect and inform participants of the purpose of this research to understand how trust and work engagement were influenced by their leaders’ approach (i.e., servant leadership) [34]. The pilot study showed understandability, validity, and appropriateness of items, with a total of 15 participants from a third university, which were not included in the final analysis.

Following [53], G*power software was used for sample size calculation, with statistical power of 80% and α 0.05 (using priori power analysis) that shows a sample size between 113 and 214 is sufficient for satisfactory statistical analysis [54]. Thus, total of 170 questionnaires were distributed among academic staff (teachers, and administrative staff), which, with 143 responses, remains an acceptable response rate (85%). As the scope and aim of this research is to examine the work engagement of employees in the academic sector, both teachers and administrative staff were considered as representatives of the population of ‘academic staff in university’. With two incomplete and three loaded responses (one answer for all items), 138 surveys were selected for the final analyses. The respondents’ profile showed 58% male and 42% female, where the majority of participants had over 3 years of work experience (88). In addition, the participants’ age range varied from 30 as the minimum and 59 as the maximum. The majority of respondents were between 30 to 40 years old (117). Furthermore, 75 participants were reported as married, while 63 were single. Each participant worked between 40–50 h a week. This was dependent on the amount of students for which they were responsible, OR during exam/registration period.

3.3. Measurements

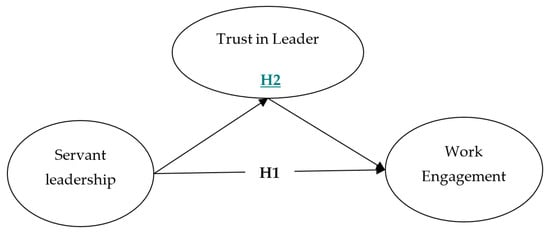

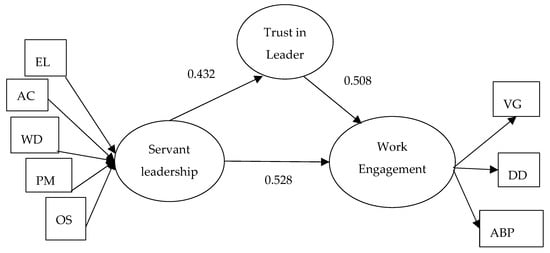

To measure servant leadership, a short version of the Servant Leadership Survey (SLS) was used as a commonly used scale among scholars, as developed by Barbuto and Wheeler (2006) [20]. Items were selected based on their relevance to theoretical framework of this research; a sample item is “manager learns from different views of others”. In addition, Organizational Trust Inventory was used to derive the questions addressing trust in the leader [55]. A sample item is “supervisor tries to gain the trust of all members”. For measuring the work engagement of employees, this research follows the work of Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova, (2006) and deploys a short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, which is a commonly used scale for analyzing the work engagement of employees. All three dimensions of work engagement; vigor (behavioral), dedication (emotional), and absorption (cognitive) [32]; with a sample item of “I am enthusiastic about my work” are included in this study; which is illustrated in Figure 1 as the proposed research model. All measurements were designed in a 5-item Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree. Servant leadership and work engagement dimensions were weighted based on the repeated indicator approach to exhibit reflective-formative latent variable [56]. This is presented in Figure 2. The survey consisted of four sections, namely demographics, servant leadership questions, work engagement items, and trust in leader indicators.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model.

Figure 2.

Path Coefficient Analysis of The Model.

4. Results

Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modeling (PLS–SEM) is used to analyze the collected data. The measurement model met the satisfactory thresholds with regards to outer loadings (more than 0.710) [57], internal consistency values of Cronbach’s alpha and Rho A, as well as composite reliability (CR) and convergent validity (CV) show acceptable levels [58,59] (above 0.7); Average Variance Extracted (AVE) calculated values are all within the satisfactory level, further stating convergent validity [54]; and heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) presents a discriminant validity that is below the threshold of 0.85 [60]. The model assessment is shown in Table 1, while HTMT is reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Measurement Model Assessment.

Table 2.

Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) values.

The VIF values are all below the threshold of 3 [57], which states that there is no issue of multicollinearity. The significance of weights and their relevance are shown in Table 1, and exhibit acceptable thresholds [61,62].

Table 3 shows the hypotheses testing conducted on the data. As can be observed, both hypotheses of the current research have been supported, direct effect (H1) (β = 0.318, t = 4.312), and indirect effect (β = 0.132, t = 2.778). The control variables (i.e., demographics) and path coefficients showed statistical significance, which are shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Hypothesis Testing.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This research examined the effects of servant leadership on academic staffs’ work engagement. The results show a significant relationship that cannot be neglected. In this sense, each dimension of servant leadership (altruistic calling, wisdom, persuasive mapping, emotional intelligence, and organizational stewardship) was found to be positively linked to dimensions of work engagement (vigor, dedication, and absorption). The current results imply that, in times of crisis, where staff are forced to change their working habits (from traditional classes to online education), servant leaders can positively influence the wellbeing of their followers through adequate use of their characteristics. These findings are in consensus with the extant literature and contribute to the development of servant leadership through self-determination theory, social learning, and social identity theory [2,12,37,39].

The current results contribute to the literature of organizational behavior, as it provides empirical evidence from the Middle East and, particularly, Turkey, which is relatively less examined when compared to its European, American, and Southeast Asian counterparts [63,64]. This expands the current understanding by highlighting servant leadership and the importance of trust on work engagement in an academic setting. While a consensus can be seen with prior studies, e.g., [2,3,5,7,65], the current research suggests that through an adequate leadership style (i.e., servant), academics can be encouraged to be more engaged with their jobs, which is highly important in developing societies, as the educational environment for future generations is enhanced. As a form of social development [66], the education sector requires a leadership approach in which employees (e.g., teachers, administrators) are provided with care and emphasis on their wellbeing [67,68]. Arguably, servant leaders are able to recognize and meet the needs of their staff through their characteristics and servant approach, which, in turn, directs their followers to show positive behaviors. This also contributes to the understanding of social learning theory, social identity theory, and social information processing theory [26,29,30]. As a result, this enables employees to exhibit positive work behavior and, particularly, work engagement.

Pertaining to the aims of the research, organizational psychology and sustainable psychology as scientific domains are taken into consideration. In this respect, the current research argues that implementing an appropriate and adequate leadership style at universities can result in positive outcomes, such as trust and engagement. Lastly, servant leadership as a positive approach is found to be highly influential in establishing trust, and thus, in improving work engagement among teachers and administrative staff at the university level. In this respect, the role of servant leaders helps create an environment where individuals can trust in the decisions and behavior of their supervisor due to their positive, trustworthy, engaging, caring, and serving characteristics. Lasting effects can be achieved through an environment of trust, where the leader serves the employees. Social development in society can be affected as an ultimate outcome of highly engaged teachers and administrators in the academic sector [66,69,70]. This is due to the impact that teachers and administrative staff have on the learning environment of students, which implies that engaged teachers are more likely to use innovative methods in their teaching, thereby leading to social development through learning and education [71,72]. Therefore, having engaged employees in the academic sector can eventually enhance the academic setting not only for staff, but for learners as well.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

In light of what was mentioned, there are both theoretical and practical implications that can be drawn based on the obtained results of the research and the aforementioned contextual literatures. In terms of theoretical contributions, it can be stated that servant leaders are capable of genuinely addressing competence, connection, and autonomy, which enables positive feelings in employees to be more engaged with their jobs [35]. Similarly, through social learning theory, these leaders are able to act as role models for their staff, which promotes learning and positive behaviors within the organization, as well as considering ethics. Academic staff can imitate their leaders’ behavior, further contributing to the overall organizational culture, and aiding the leaders to achieve sustainable psychological outcomes [18,26]. This is also linked to the premise of social identity theory, in which staff can be encouraged through a sense of identification that is supported by their leader and/or peers (social learning) [27,29,30]. Hence, the current results provide a better understanding on the interconnectedness of these theories, and their adequacy within the context of leadership in the academic sector after the global COVID-19 pandemic. Servant leaders are able tap into the sense of identification, autonomy, and competence of their followers, which, combined with the element of trust, has led to higher work engagement levels. The current findings show that trust in a leader is a mediating factor for the servant leadership–work engagement linkage. Servant leadership has shown to be influential for a number of psychological elements, including trust, for a positive outcome. This has been supported by the extant literature [3,11]. Through path goal theory [73], it is implied that servant leaders guide their followers based on their needs. Servant leaders are constantly providing support to their followers, which further develops trust and allows staff to engage in positive behaviors. In the academic sector, which requires high levels of performance and is demanding, such leaders can play a major role in delivering adequate information and the support that is imperative for positively influencing the behavior of their staff.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study aims to contribute to leadership in the academic sector through a number of practical implications that can be beneficial for decision-makers in this sector. This, particularly, can be more vivid for the Middle East region, and Turkey, specifically. The importance of a ‘serving’ leader, who focuses on building trust with employees and implementing tactics that increase their work engagement cannot be neglected in the academic sector. Servant leaders are able to foster trust and engage in positive interactions, an overall approach that provides a workplace for staff where they are encouraged to exhibit positive organizational behaviors (i.e., work engagement). Notably, this implies that through adequate leadership styles, the psychological wellbeing of academic staff can be improved, as they can trust their leaders to enable professional and personal development while considering their needs and interests. The ultimate understanding from the current results can be the role of servant leaders in creating a soothing workplace for academic staff in the post-pandemic era and in a high-performing industry (i.e., education). It is essential that decision-makers in universities implement strategies that attract, recruit, and/or develop leaders, who can appropriately and positively impact employees’ psychology to achieve long-term goals.

Linked to the occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic, servant leaders can be highly effective in managing the emotions and organizational behavior of their staff, as they provide personal care, which is vital for employees, to better cope with the outcomes of the pandemic (i.e., stress, anxiety, work-life conflict, and loneliness) [34,74]. The current findings support the aforementioned statement. The academic sector is highly competitive, which makes the organizations high performing [5,15]. Therefore, the role of servant leaders in creating work–life balance and enhancing the overall wellbeing of academic staff is emphasized. The current findings imply that schools or universities can greatly benefit from deploying servant leadership in their organizations. Accordingly, servant leaders can greatly enhance work conditions as well as creating bonds with their followers. During times of change and uncertainty, servant leaders have shown to be vital for academic staffs’ work engagement, with the emphasis on their wellbeing, stress and anxiety, and motivation, while providing assistance and training, and fostering trust as a psychological element [3,34].

Following what was noted, the current research addresses sustainable psychology as a scientific domain that inherently encompasses wellbeing.

The current results show the importance and influence of adequate approaches (i.e., servant leadership) and factors to be considered (i.e., emphasis on trust-building, and increasing work engagement). This positively impacts the wellbeing of individuals in an academic setting. HRM departments of universities can deploy initiatives that increase work engagement by reducing stress and anxiety, thereby providing a positive and honest environment, providing support, better connecting with leaders, and enhancing the wellbeing of academic staff [7,51,75,76], and considering negative factors, such as loneliness [40], work–life balance and autonomy [74], and loneliness during remote working hours [34], with the goal of generating sustainable and positive employee outcomes. Consequently, universities will benefit from this, as resilience [41], flexibility, and ethical conduct become the core strategies of their leaders. It is also important to mention the relatively weak mediation effect that was noted in the current results. This can be due to the other factors that are influential in this context but are not included in the current model (e.g., organizational support, leader-member exchange, team-member exchange, personal characteristics, and social or cultural elements). These aspects can be addressed by scholars aiming to develop a current understanding of the domains of sustainable psychology, leadership, and organizational behavior.

6. Limitations and Future Research

The current research was limited in a number of elements. Firstly, this study was conducted in a cross-sectional manner. Future studies can conduct longitudinal data collection [77] to address the changes in time regarding academic staff and their organizational behavior under the presence of servant leaders. Furthermore, the proposed model was controlled regarding other factors (i.e., demographics). Differences among academic staff based on their age, gender, marital status, and other characteristics can be examined by scholars interested in the psychological aspects of academics or other high-performing sectors (e.g., IT). Similarly, the effect and influence of other factors can be included in future studies to provide a better understanding regarding the underlying and relevant effects (e.g., organizational support, work–life balance, coping strategies, emotional contagion, and cultural intelligence). Therefore, future studies can focus on developing the theoretical model proposed in this study by including relevant factors that encompass psychology, behavior, and/or leadership in the academic sector. Regarding the representativeness of the sample, the current research surveyed teachers and administrative staff at two universities. This limits the representativeness degree of the data in a considerable manner. An expansion of the data sample size and the inclusion of deans, assistants, and managers could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the subject at hand. This could yield benefits for strategic development and planning in the academic sector in the country, and subsequently, in the region. Additionally, the current research is limited in terms of theory. In this sense, the effects of leaders on work engagement during and/or after COVID-19 can be assessed through other theories, such as Job Demands–Resources and path goal theory. This can help with comprehending the various aspects of academic jobs and the impacts on the psychological wellbeing within the sustainable psychology domain. The current research used short versions of the SLS and Work Engagement scales. Future studies can include more items to increase the validity and reliability of the measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.E.Z.M.R. and P.F.; methodology, P.F.; software, F.E.Z.M.R.; validation, P.F. and F.E.Z.M.R.; formal analysis, F.E.Z.M.R.; investigation, F.E.Z.M.R.; resources, F.E.Z.M.R.; data curation, P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, F.E.Z.M.R.; writing—review and editing, P.F.; visualization, F.E.Z.M.R.; supervision, P.F.; project administration, P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1999, 13, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuypere, A.; Schaufeli, W. Leadership and work engagement: Exploring explanatory mechanisms. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 34, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanesh, P.; Zargar, P. Trust in Leader as a Psychological Factor on Employee and Organizational Outcome; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Raja, U.; Matsyborska, G. Servant Leadership and Work Engagement: The Contingency Effects of Leader-Follower Social Capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2014, 25, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, O.; Atkinson, R.; Noury, L.; Ruotsalainen, R. Work-life balance policies in high performance organisations: A comparative interview study with millennials in Dutch consultancies. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 35, 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, W.; Rasool, S.F.; Asghar, A.; Chin, T. The Linkage between Ethical Leadership, Well-Being, Work Engagement, and Innovative Work Behavior: The Empirical Evidence from the Higher Education Sector of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Samma, M. Sustainable Work Performance: The Roles of Workplace Violence and Occupational Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.; Cooper, C. Well-Being: Productivity and Happiness at Work; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W. A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K. The Servant as Leader; Center for Applied Studies: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Zargar, P.; Sousan, A.; Farmanesh, P. Does trust in leader mediate the servant leadership style—Job satisfaction relationship? Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 2253–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhof, J.G.; Güldenberg, S. Servant Leadership: A systematic literature review—Toward a model of antecedents and outcomes. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 32–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Barbour, J.P. Relationships of individual and organizational support with engagement: Examining various types of causality in a three-wave study. Work Stress 2014, 28, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, L. How can personal development lead to increased engagement? The roles of meaningfulness and perceived line manager relations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 51, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayya, S.S.; Martis, M.; Ashok, L.; Monteiro, A.D.; Mayya, S. Work-Life Balance and Gender Differences: A Study of College and University Teachers from Karnataka. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211054479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.S.; Heine, G.; Mahembe, B. Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, W.I., Jr.; Murfield, M.L.U.; Baucus, M.S. Leader emergence: The development of a theoretical framework. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2014, 35, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J.D. Servant Leadership and Serving Culture: Influence on Individual and Unit Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, M.J. Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World, 3rd ed.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barbuto, J.E.; Wheeler, D.W. Servant Leadership Questionnaire; PsycTESTS Dataset; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennaker, M. Servantleadership: A model aligned with chaos theory. Int. J. Servant-Leadersh. 2006, 2, 427–453. [Google Scholar]

- Aboramadan, M.; Dahleez, K.; Hamad, M.H. Servant leadership and academics outcomes in higher education: The role of job satisfaction. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 29, 562–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, B.T. The Best Leadership Model for Organizational Change Management: Transformational Verses Servant Leadership. 2009. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1418796 (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Greenleaf, R.K. The Power of Servant-Leadership: Essays; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Liden, R.C. Antecedents of team potency and team effectiveness: An examination of goal and process clarity and servant leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2nd ed.; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasco-Saul, M.; Kim, W.; Kim, T. Leadership and Employee Engagement: Proposing research agendas through a review of literature. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, W.; Qiu, C.; Yim, H.K.; Wan, J. The impact of CEO servant leadership on firm performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 945–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and Measuring Work Engagement: Bringing Clarity to the Concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- El Telyani, A.; Farmanesh, P.; Zargar, P. The Impact of COVID-19 Instigated Changes on Loneliness of Teachers and Motivation–Engagement of Students: A Psychological Analysis of Education Sector. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.S.; Cheshire, C.; Rice, E.R.W.; Nakagawa, S. Social Exchange Theory. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.-C.; Tian, Q.; Liu, J. Servant leadership, social exchange relationships, and follower’s helping behavior: Positive reciprocity belief matters. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. Engaging leadership in the job demands-resources model. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Karatepe, O.M. Does servant leadership better explain work engagement, career satisfaction and adaptive performance than authentic leadership? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2075–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Song, M.; Yoon, H. The Effects of Workplace Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Moderating Roles of Leader-Member Exchange and Coworker Exchange. Sustainability 2021, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.; Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M. Examining the Predictors of Resilience and Work Engagement during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M. Do Organizational Health Climates and Leader Health Mindsets Enhance Employees’ Work Engagement and Job Crafting Amid the Pandemic? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic Leadership: Development and Validation of a Theory-Based Measure†. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Oke, A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, V.; Rangnekar, S. Servant leadership, employer brand perception, trust in leaders and turnover intentions: A sequential mediation model. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2016, 10, 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.C.; Mak, W.-M. The impact of servant leadership and subordinates’ organizational tenure on trust in leader and attitudes. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Liu, F.; Wu, X. Servant Versus Authentic Leadership. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 58, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Xu, L. Servant Leadership, Trust, and the Organizational Commitment of Public Sector Employees in China. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Samma, M.; Anjum, A.; Munir, M.; Khan, T.M. Relationship between modern human resource man-agement practices and organizational innovation: Empirical Investigation from banking sector of China. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, R.C.; Marlowe, H.A., Jr. Development and Psychometric Properties of the Organizational Trust Inventory. Evaluation Rev. 1997, 21, 614–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika 1971, 36, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using smartPLS 3.0.; Pearson: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Cheah, J.-H.; Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M. How to Specify, Estimate, and Validate Higher-Order Constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Gul, R.; Tufail, M. Does Servant Leadership Stimulate Work Engagement? The Moderating Role of Trust in the Leader. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, S.; Mostafa, A.M.S.; Pereira, V.; Wang, X.; Del Giudice, M. Servant leadership, CSR perceptions, moral meaningfulness and organizational identification-evidence from the Middle East. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafeshat, R.; Tanova, C. Servant leadership style and high-performance work system practices: Pathway to a sus-tainable Jordanian airline industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, V.N.; Wirtz, J.; Kunz, W.H.; Paluch, S.; Gruber, T.; Martins, A.; Patterson, P.G. Service robots, customers and service employees: What can we learn from the academic literature and where are the gaps? J. Serv. Theory Pr. 2020, 30, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, R.A.; Atan, T. The influence of ethical leadership on academic employees’ organizational citizenship be-havior and turnover intention: Mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Manag. Decis. 2018, 57, 583–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torlak, N.G.; Kuzey, C. Leadership, job satisfaction and performance links in private education institutes of Pakistan. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S. The Relationship between Psychological Capital and Stress, Anxiety, Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Job In-volvement. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2018, 75, 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, G.; Chen, X.; Cheung, H.Y.; Peng, K. Teachers’ growth mindset and work engagement in the Chinese educa-tional context: Well-being and perseverance of effort as mediators. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; Fernandes, F.A.P. Innovations in Teaching and Learning: Exploring the Perceptions of the Education Sector on the 4th Industrial Revolution (4IR). J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klofsten, M.; Fayolle, A.; Guerrero, M.; Mian, S.; Urbano, D.; Wright, M. The entrepreneurial university as driver for economic growth and social change-Key strategic challenges. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 141, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Mitchell, T.R. Path-Goal Theory of Leadership; Washington University Seattle Department of Psychology: Seattle, WA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Khawand, S.; Zargar, P. Job autonomy and work-life conflict: A conceptual analysis of teachers’ wellbeing during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Wang, Z.; Rasool, S.F.; Zaman, Q.U.; Raza, H. Impact of critical success factors and supportive leadership on sustainable success of renewable energy projects: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Rasool, S.F.; Ma, D. The relationship between workplace violence and innovative work be-havior: The mediating roles of employee wellbeing. Healthcare 2020, 8, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Q.; Nawab, S.; Hamstra, M.R.W. Does Authentic Leadership Predict Employee Work Engagement and In-Role Performance? Considering the role of learning goal orientation. J. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 15, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).