Abstract

This study investigates the effects of tourism storytelling on the tourism destination brand value, lovemarks and relationship strength. The survey data was collected from 259 respondents who had experienced tourism storytelling in South Korea. Among the determinants of tourism storytelling, uniqueness, interestingness and educability have significant effect on tourism destination brand value. Sensibility, descriptiveness and interestingness have significant effect on the lovemarks formation. Both brand value and lovemarks are found to affect relationship strength. The study further found that the rational factor has more influence on the brand value whereas the emotional factor has more influence on the lovemarks. The study made a theoretical contribution by examining whether tourism storytelling affects lovemarks and could boost relationship strength. The managerial implication of this study is that DMO should make efforts to form a lovemarks for tourism destinations.

1. Introduction

A destination marketing organization (DMO) is an organization which is a strategic leader in destination development to drive and coordinate all the elements such as marketing, attractions, amenities, access and pricing that make up a destination [1,2]. DMOs are generally tied to local government infrastructure, often with supporting funds being generated by tourism taxes. Tourism taxes constitute an important financial resource for local governments and tourism authorities to both ensure tourism sustainability as well as enhance the quality of tourist experiences [3]. DMO success factors include supplier relations, effective management, strategic planning, organizational focus and drive, as well as proper funding and quality personnel. To succeed in the destination promotion, factors such as location and accessibility, attractive product and service offerings, quality visitor experiences and community support are essential [4].

In Korea, the Korea Tourism Organization (KTO) started a pilot project to foster a regional tourism promotion organization (DMO) and selected 17 local governments, including 5 tourism base cities and 12 basic municipalities selected for the DMO project in 2018. The selected entitities are to lead in regional tourism promotion. The country is in the infant stage of nurturing organizations that can lead in tourism promotion [5].

One of the marketing tools for DMOs is storytelling. Storytelling is a promising means of forming a destination brand [6] and is used as a marketing tool to advertise tourist attractions, create tourist-brand relationships, and maximize travel experiences [6,7,8]. Storytelling is increasingly attracting attention in the field of tourist destination development and strategic planning [9,10]. It is often used commercially because humans are familiar with stories, and storytelling helps define human nature [11,12]. Historically, stories, including myths, legends, and folktales, have passed on wisdom, knowledge and culture between humans for thousands of years [13,14]. Storytelling about tourism destinations can be used as a strategic marketing tool to attract tourists to tourism destinations [13]. Furthermore, it enhances persuasion in appealing tourist attractions by delivering stories related to tourist destinations and attractions. Tourism storytelling has a wide range of meanings, which contains not only verbal narrative genre but also nonverbal means as the new way of communication in modern society, such as movies and TV shows [15].

Brand value is defined as the extra monetary value that consumers are willing to pay to purchase a particular brand by comparing alternative brands with similar functions [16]. A great storytelling related to tourism destination increases the brand value of the tourism destination [17] and has a significant effect on brand names [7,18]. It can convey the value of tourist attractions to tourists as well as give them emotional value [19].

Storytelling related to tourism destination affects not only the brand value of a tourism destination but also the formation of lovemarks [20]. Roberts [21] defines lovemarks as love and respect for the brand and argues that lovemarks is the next step in branding. Lovemarks can form and strengthen the emotional bond between brands and consumers. Tourism brands should make more effort to form emotional connections with tourists [22,23,24]. Moreover, brand value and lovemarks can effectively strengthen the relationships between the tourism destinations and tourists [22,25,26,27].

In the previous studies related to tourism storytelling, researchers investigated the relationship between tourism storytelling and tourism destination development [9], tourism marketing [13], destination brand [28] or behavioral intentions [29,30,31]. Nevertheless, in order to revitalize local tourism in destination marketing organization, it is important to increase the brand value by promoting the unique storytelling of the region and to increase relationship strength by forming an emotional response like lovemarks. However, only a small amount of research has been done in relation to that subject [32,33,34]. Chen et al. [32] examined the relationships among night tourism experience, lovemarks, brand satisfaction and brand loyalty. They studied the effect of tourism experience on the emotional part, lovemarks, but overlooked the effect on the rational part, brand value. In the study of Lee and Seo [33], the relationship between lovemarks, brand identification, brand equity, and behavioral intentions of tourist destinations was verified, but this study did not discuss how to form lovemarks. Seo and Lee [34] studied the relationship among attractions, experience, lovemarks and attachment, but they did not verify the role of storytelling.

This study’s purpose is to examine the effects of tourism storytelling on brand value, lovemarks and relationship strength. Additionally, the study investigates which factor between brand value and lovemarks bears greater influence on the formation of relationship strength to tourism destination.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Storytelling

In the era of storytelling, without a story, tour destinations or services cannot appeal to consumers because humans are ‘homonarran’ [35]. Human history is told in myths, fairy tales and legends consisting of words, images and stories [14]. All great religions and cultures have expressed their central doctrines through one or more stories [36]. Storytelling is a compound word of ‘story + telling’, meaning all narrative genres with stories [6]. It includes not only narratives in languages such as folk tales, tales, legends and fairy tales, but also non-verbal narratives such as movies, TV shows, music videos, cartoons, games and advertisements [15].

In the tourism sector, storytelling is the process of creating shared value (new story) while interacting through the entire process of discovering, experiencing and sharing stories [37]. Storytelling satisfies tourists’ desire for a specific value and deeply impresses the destination [38]. Tourism storytelling recognizes humans as interacting beings and is defined as a semantic system created by tourist destinations and tourists, focusing on the stories surrounding tourist attractions. It is believed that stakeholders such as tourists, tour guides and local residents are creating a common emotional relationship for tourists’ experiences and memories [39]. Storytelling works in conjunction with the activities carried out by tourists. It can be organized into stories related to tourist destinations and shared with tourists via social media, travel records and tour guide’s explanation or commentary [40]. The message centered on the story in tourism is easy to communicate with tourists and is sufficient to stimulate symbolic and empirical elements. Therefore, the role of storytelling is important when introducing tourist destinations and services at many tourist destinations [37].

Choi [15] insisted that storytelling is composed of five factors such as understandability, interestingness, educability, uniqueness and sensibility. Yang [41] argues that storytelling has five factors like interestingness, educability, sensibility, descriptiveness and uniqueness. Interestingness is a concept that includes various stories, mysterious charm, and interest [42]. Bae et al. [43] said that story interestingness is divided into cognitive interest and emotional interest. Educability includes understanding of a tourist destination, fulfillment of knowledge needs, and social and cultural connotation [42]. Sensibility is a concept related to evoking emotions, memories and romance, and pleasurable experiences [42]. Descriptiveness refers to the extent to which the intended idea is structurally organized in storytelling [30]. Uniqueness is related to understanding native culture and indigenous knowledge [42].

As a result of previous studies [41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], it was found that among the components of storytelling, tourism destination storytelling components that can be applied to tourist destinations are interestingness [41,43,47], educability [41,43,49,50], sensibility [41,43,50], descriptiveness [41,43,50] and uniqueness [42,50]. Therefore, they were composed of factors of storytelling in this research.

2.2. Brand Value in Tourism Destination

Brands connect consumers with products, and many customers become aware of the brand as they continue to find its efficiency [51]. They also express their preferred characteristics through continuous relationships with brands [41]. In the tourism industry, the name of the tourist destination usually serves as the brand. For example, the name of the attraction reflects the consumer’s preference, the overall level of destination and its popularity [16]. Storytelling can be a promising means of forming a destination brand [6]. Storytelling is also recognized as having the purpose and strategic method of realizing the resources of a tourist destination as a strategic concept and can make tourists interested in the region, change perspectives, and induce interest in value change [44]. Moscardo [44] views storytelling as an important aspect of changing the perspective of tourists and inducing them to be interested in particular tourist attractions. Moreover, storytelling satisfies the tourist’s imaginary value by allowing them to experience stories at tourist attractions.

Researchers also contend that storytelling increases brand value, brand liking and satisfaction [7]. This is because storytelling is a view of the environment of the destination and an educational activity that accumulates experience and information. Moreover, it induces interest by interpreting the meaning of the delivered information [6]. Through direct experience, the contents of the story are related to tourist attractions in various ways. Rather than the facts of the tourist destination, the overall content and approach of storytelling build up educational, informational and understanding of the destination. On the other hand, storytelling minimizes the negative impact of resource use by enhancing the understanding of the value of resources and informing visitors in advance [7]. Most importantly, storytelling focuses on securing the reliability of tourist attractions, such as describing and clarifying historical facts about tourist attractions. Harris [18] in their study proved that storytelling has a positive effect on the brand’s name and memory and that there is a significant difference in brand name and memory depending on the large and small number of storytelling. Moscardo [44] stated that the storytelling includes novelty, collision and theme of the destination. It also persuades interests and educational motivation to increase tourism satisfaction.

2.3. Lovemarks in Tourism Industry

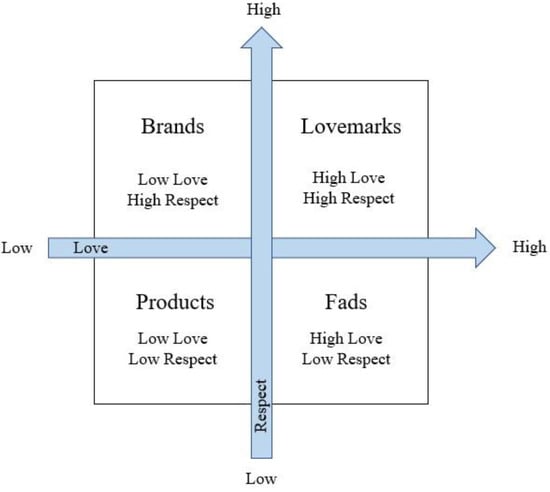

As the intensity of the consumer’s feeling and experience about the brand increases, the consumer and the brand become closely intertwined and powerful [52]. Emotional exchanges between consumers and brands trigger positive or negative consumer reactions of which positive consumer reactions soon lead to strong immersion in brands. A positive experience of a product can positively affect the brand loyalty of consumers as well as the emotion and enthusiasm for the product [53]. Lovemarks is a concept suggested by Roberts [21], CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi, emphasizing the importance of brand sensibility based on experience (see Figure 1). Roberts [21] compared lovemarks with brands, stating that if brands value mass media information, progress and product quality, lovemarks values emotional attachments such as experience, story, sensibility, mystery and passion. Most importantly, the emotional bond with the brand, once formed, has a characteristic that does not easily change [22]. Lovemarks strengthens the emotional bond between consumers and brands and is a strong and exclusive relationship that enables intimacy and emotional connection as well as consumer awareness [23,24].

Figure 1.

The classification of lovemarks (Roberts [21]; Chen et al. [32]).

Prior research on lovemarks was mainly conducted based on the definition and concept of lovemarks suggested by Roberts [21]. Cho [54] analyzed the review contents of lovemarks in social media sites and conducted a study on the conceptual establishment of lovemarks dimension through individual interviews. Bradley et al. [55] exposed the logo to experimenters for 32 brands and evaluated and measured them using language differences. Pawle and Cooper [23] extracted an online panel group and measured and compared lovemarks awareness for brands. The study found that intimacy and novelty had the greatest influence on love and respect.

As competition between tourism destinations intensifies, lovemarks as well as brand value of tourism destinations have become important. Lovemarks is love and respect for a particular brand. In the tourism industry, lovemarks means love and respect for a tourism destination, restaurant or coffee shop brand [27]. In the field of tourism, Chen et al. [32] studied the relationships among night tourism experience, lovemarks, brand satisfaction, and brand loyalty. They indicate that ‘Cultural Heritage Night’ tourists’ entertainment and educational experiences have a significant impact on their lovemarks. Song et al. [27] examined the relationships between a brand-name coffee shop’s image, satisfaction, trust, lovemarks, and brand loyalty. Brand love and respect were found to significantly moderate the relationship between trust and brand loyalty. It means that the lovemarks theory is useful for exploring the development of brand loyalty generation.

2.4. Relationship Strength in Tourism Industry

Relationship strength refers to the level of customer commitment to employees and implies the degree, size and importance of customer trust in services [56]. Relationship strength reflects how strongly customers feel about their service relationship with their employees, implying that strong relationships are more likely to persist [52]. According to Donaldson and O’Toole (2000) [57], relationship strength is defined by the interaction process between employees and customers. In particular, this formed relationship creates enduring value because it cannot be easily regenerated. On the other hand, Hausman [58] asserted that relationship strength is defined as a summary constituent concept that includes commitment, trust and relationalism. If this focuses more on relational attitudes, a bond between the parties is established and can overcome internal and external challenges to the relationship. Similarly, Hewet et al. [59] and Bove and Johnson [60] viewed relationship strength as a factor consisting of trust and immersion.

When tourists have positive emotions from their experiences, they are likely to form connection, that is, a relationship [61]. Lee [62] studied the effect of brand congruity on tourism destination on lovemarks and relationship continuity intention. As the result of the study, lovemarks was found to affect relationship continuity intention. And Kim [63] conducted research focusing on the mediating effect of lovemarks on tourism storytelling and tourist relationship strength. Storytellers have been shown to influence lovemarks formation and ultimately enhance relationship strength.

3. Methodology

3.1. Hypothesis Formation

H1.

Tourism storytelling has a significant influence on brand value.

H2.

Tourism storytelling has a significant influence on lovemarks.

H3.

Brand value has a significant influence on lovemarks.

H4.

Brand value has a significant influence on relationship strength.

H5.

Lovemarks has a significant influence on relationship strength.

Moin et al. [7] insisted that storytelling increases brand value, brand liking and satisfaction. Kim [18] argues that storytelling can convey the value of a product to consumers and gives emotional value beyond rational values such as function and price of the product. Lee [64] compared and evaluated the brand value of tourist destinations by assuming that the tourist destination is a tourist brand and selected ten regions designated as special tourist zones and 20 overseas tourist destinations. The determinants of tourist brand value examined were defined as tourist attraction awareness, destination preference, destination value for vision, destination uniqueness, destination population and price premium. Aaker [65] cited four factors that determine the value of a brand: (i) awareness of the brand, (ii) loyalty, (iii) consumer-recognized quality of products, and (iv) association associated with the brand. Kim [42] argued that the components of tourism storytelling, such as ease of understanding, emotion, education, attractiveness and interest, all have significant influence on the brand value perception of tourist destinations. Based on the above literature, this study hypothesizes as follows:

H1.

Tourism storytelling has a significant influence on brand value.

According to Roberts [21], to form a lovemarks, which can be called tourists’ attachment to tourist attractions, new and interesting storytelling must exist, and only continuous innovation can interest tourists and make them feel intimate. In addition, through storytelling, tourists communicate with each other, feel bonds or empathy, and as a result, intimacy is formed, making it easier to form a lovemarks. Yang et al. [45] investigated whether the lovemarks of tourist attractions can vary depending on the storytelling elements. They argued that emotional sensitivity, education, uniqueness, socio-culturalism, descriptiveness and interest are measured as six important factors in this process. In particular, they agreed that the descriptive story claimed by Brewer and Liechtemstein [66] helps induce a strong image. The authors further stated that if storytelling for emotional experiences is provided, tourists will be connected to emotions, and the tourist destination will form a strong lovemarks. Looking at the existing literature, it can be suggested that tourism storytelling attributes have a positive effect on the lovemarks of tourist attractions. Accordingly, the following hypothesis was established based on previous studies:

H2.

Tourism storytelling has a significant influence on lovemarks.

Consumers’ perceived value could affect consumer brand perception of emotional relationships. Chaudhuri and Holbrook [67] defined perceived value as practical value and hedonic value and examined the relationship between perceived brand value and brand attachment formation. The study found that perceived value has a positive effect on brand attachment formation. In the study of tourist attractions by Yang [41], it was demonstrated that the brand value perception of tourist attractions had a positive effect on the perception of lovemarks. It was also revealed that the brand value perception of tourist destinations plays a salient role in providing intimacy and trust among the components of the lovemarks. Finally, it is observed that there can be a positive causal relationship between brand value perception and tourist lovemarks. Hence, the following hypothesis was established between the perceived value of tourist attractions and the perception of lovemarks:

H3.

Brand value has a significant influence on lovemarks.

Some studies have found that storytelling of tourist destinations has a positive effect on tourists’ evaluation of tourist destinations [7]. Additionally, immersion due to friendly feelings toward tourist attractions also has a positive effect on future behavioral immersion. Behavioral commitment can be understood as a visitor’s future will to maintain and further strengthen the relationship while making sacrifices to a certain extent [63]. Customer cocreated brand value generates tie strength and network cohesion [68]. Pawle and Cooper [23] explained the interaction between rational process and emotion and proposed the ways to form a brand relationship. Importantly, effective storytelling affects lovemarks, an emotional valuation of tourists, and it is believed that lovemarks will further strengthen the relationship between tourists to tourist destinations. Therefore, the following hypotheses are suggested:

H4.

Brand value has a significant influence on relationship strength.

H5.

Lovemarks has a significant influence on relationship strength.

3.2. Data Collection

A self-administered online survey was conducted by Google survey from 1 November to 6 November 2019, with 290 Korean tourists aged over 20 who have experienced tourism storytelling. Thirty-one respondents did not fully answer the questions; hence a total of 259 responses were used for the actual final analysis. The survey asked the respondents to fill out the questions by recalling the experience of listening to tourism storytelling at a tourist destination. At the beginning of the questionnaire, the definition and examples of tourism storytelling were suggested to improve the respondents’ understanding.

3.3. Measurement Scales

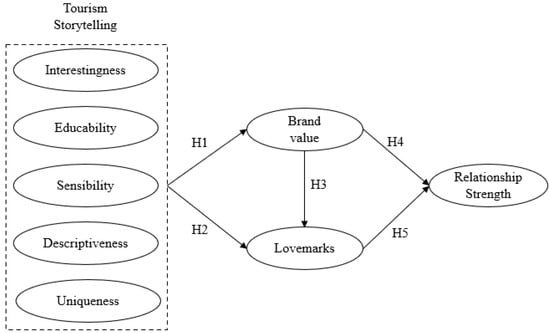

The survey consisted of five parts. Part 1 asked questions about tourism storytelling, using five factors and 20 items adapted from Kim [42] and Yang [40]. Part 2 asked questions about brand value with five items from Yang [40]. Brand value refers to the value of the brand, which increases as consumers change their thoughts on the destination [44]. Part 3 asked questions about lovemarks with five items from Roberts [21], and Pawle and Cooper [23]. Part 4 asked questions about relationship strength with three items from Kim [42]. Relationship strength corresponds to dependence on people as they trust them and gradually strengthen their trust [56]. Part 5 presented questions designed to get demographic information, including gender, age, educational background, income level and residence area. The study’s constructs and their related items are presented in Appendix A, Table A1. Each questionnaire was scored using a Likert 5-point scale of 1 for ‘not at all’ to 5 for ‘very much’. The theoretical framework of this study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The study used SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 22.0 to analyze the data. The researchers applied a two-step approach to the analysis. The first step was to confirm the relationship between measured variables with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In the second step, a structural equation model was used to verify the causal relationship between hypothesized structures, and the proposed model was tested.

For the analysis, frequency analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, reliability analysis, and correlation analysis were performed and structural equation model verification procedures.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profiles

The demographic characteristics of the sample were observed as follows: gender was 53.3% (n = 138) for men and 46.7% (n = 121) for women. The age of respondents is as follows: 39.8% (n = 103) for 20–29 years old, 14.7% (n = 38) for 30–39 years old, 19.3% (n = 50) for 40–49 years old, and 26.3% (n = 68) for 50 years or older. As for occupations, 26.6% (n = 69) are college students, 19.7% (n = 51) are full time employees, 9.3% (n = 24) are sales employees, 6.9% (n = 18) are professionals, 6.6% (n = 17) are production employees, 24.7% (n = 64) are self-employed, 3.5% (n = 9) are homemakers, and 2.7% (n = 7) are unemployed.

4.2. Measurement Model

The reliability and validity of the resulting measurement scales were assessed as follows: First, the reliability of the constructs was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (see Table 1). The reliability coefficients for the constructs ranged from 0.695 to 0.914, which is considered satisfactory [69]. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS 22.0 software and used to evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement items. The measurement model fits well with the data, as provided by the fit statistics for the model χ2 (432) = 516.449; p < 0.005, GFI = 0.896, AGFI = 0.865, NFI = 0.917, RFI = 0.898, TLI = 0.942, CFI = 0.945, RMSEA = 0.028, RMR = 0.027. Across the measurement models, the factor and item loadings all exceeded 0.5, with all t-values greater than 2.58, demonstrating the convergent validity among our measures. All the measures provided high reliability, with composite reliabilities ranging from 0.840 to 0.937 (see Table 1). The researchers further investigated the qualification for discriminant validity among variables, as suggested by Fornell and Larcker [70]. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were all larger than the squared correlation between the construct and any others (see Table 2). Therefore, overall, the constructs showed good measurement properties.

Table 1.

Reliability and confirmatory factor analysis results for attributes.

Table 2.

Construct means, standard deviations and correlations.

4.3. Structural Model Testing

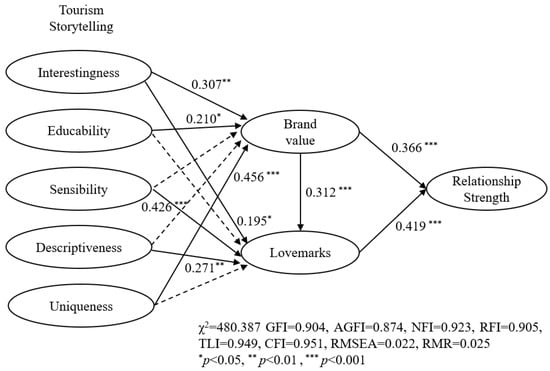

The paper uses a structural equation model method to examine the hypothesized relationships. The fit indices of the research model are generally acceptable (Table 3). Therefore, the research model χ2 (429) = 480.387; p < 0.05, GFI = 0.904, AGFI = 0.874, NFI = 0.923, RFI = 0.905, TLI = 0.949, CFI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.022, RMR = 0.025 is deemed to fit well with the collected data. Figure 3 and Table 3 present a summary of the tested hypotheses.

Table 3.

Summary of the research model.

Figure 3.

The results of the structural model.

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

The results of the analysis of Hypothesis 1 show that being interesting (H1_1, β = 0.307, CR = 3.201, p < 0.01), educability (H1_2, β = 0.210, CR = 1.966, p < 0.05), and uniqueness (H1_5, = 0.456, CR = 0.451) all have a significant impact on brand value. The analysis of influence of tourism storytelling on brand value indicates that uniqueness (β = 0.456), being interesting (β = 0.307) and educability (β = 0.210) have a statistically significant and positive impact on brand value. On the other hand, sensibility and descriptiveness are not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is partially accepted. The test results of Hypothesis 2 are as follows: Being interesting (H2_1, β = 0.195, CR = 2.164, p < 0.05), sensibility (H1_3, β = 0.426, CR = 4.457, p < 0.001), descriptiveness (H1_4, β = 0.271, CR = 3.148, p < 0.01) all showed positive and significant impact on lovemarks. The test of the influence of tourism storytelling on lovemarks was in the order of sensibility (β = 0.426), descriptiveness (β = 0.271), being interesting (β = 0.195), which all have a significant impact on lovemarks. Nonetheless, whereas uniqueness (H2_5, β = −0.174, CR = −2.037, p = 0.05) is statistically significant, the direction of the coefficient of correlations is reversed, thus rejected. Educability is not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is partially accepted.

In the next analysis, Hypothesis 3 was examined. The effect of brand value on lovemarks (H3, β = 0.312, CR = 3.920, p = 0.001) is positive and statistically significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is accepted. For Hypothesis 4, the effect of brand value on relationship strength (H4, β = 0.312, CR = 3.920, p = 0.001) is positive and significant, implying that brand value has a positive impact on relationship strength. Thus, Hypothesis 4 is also accepted. Lastly, Hypothesis 5 was tested, and the result shows that the effect of lovemarks on relationship strength (H5, β = 0.419, CR = 5.222, p = 0.001) is statistically significant. The influence on relationship strength was in the order of lovemarks (β = 0.419) and brand value (β = 0.366), both of which entered the model with statistically significant coefficients. Hence, Hypothesis 5 is accepted.

5. Discussion

Tourism destination marketing is a key component in the management of destinations [71], and storytelling appears to be an important aspect. If excellent storytelling is developed to attract tourists, tourism destination marketing strategy can be carried out efficiently and strategically at a lower cost [6]. The objective of this study was to determine whether tourists perceive brand value of tourist destinations through storytelling experiences and to clarify the structural causal relationship between tourists and tourist destinations through quantitative research.

The key finding of this study can be summarized as follows. Following the analysis of the structural relationship between tourism storytelling, brand value, lovemarks and relationship strength, brand value was affected in the order of uniqueness, interestingness and educability. Among the five determinants of tourism storytelling, sensibility, descriptiveness and interestingness were found to influence lovemarks formation. In addition, sensibility was found to have the greatest influence on the formation of lovemarks. In the study of Yang [41], it was found that brand value perception was influenced in the order of sensitivity, education, description, and interestingness among tourism storytelling. Among the factors that make up storytelling, the fact that interestingness and education affect brand value is similar to our research result. This means that these two elements are important in storytelling. As shown that the awareness of the brand value of tourist attractions has the positive (+) effect on lovemarks of tourist attractions, the part of tourism storytelling can be utilized as the differentiation strategy of destination marketing was empirically verified. This result is consistent with the results of this study. In another study [63], it was found that the factors of storytelling affect the formation of lovemarks and that lovemarks affect the relationship strength, which was consistent with the results of this study.

In economics, value is the utility derived from the price paid by the customer to enjoy a product or service. There must be appropriate benefit for the price, including time to search for information about the tourism destination and cost of visiting the tourism destination. Only then will the tourist determine whether the brand value of tourism destination was appropriate for the cost incurred. The determination of brand value is related to rational judgment. If storytelling contents have uniqueness that cannot be found anywhere else, are interesting and have educational meaning, tourists may find it worth visiting the tourist destination. On the other hand, lovemarks refers to the emotional element of affection and respect for the tourist destination. As such, if there is an element that stimulates sensibility in storytelling, a lovemarks is formed. When a tourist destination is wrapped up with an attractive story, its value and affection increase without having to invest excessively. Furthermore, as a tourist destination stimulates emotions of tourists, it will be possible to increase the intensity of the relationship effectively.

6. Conclusions

There are theoretical contributions developed from the current study. First, the results are theoretically meaningful in that this study investigated whether various determinants of tourism storytelling improve the brand value of the tourist destination and definitively revealed which among those factors can form a strong lovemarks for tourist destinations. Second, lovemarks can be used to build and strengthen emotional ties between consumers and brands [23]. Additionally, lovemarks towards a tourist destination can be achieved through major attributes such as novelty, familiarity, attractiveness, sensibility, attachment and trust of tourist attractions [63]. Consequently, this study made an academic contribution in deriving a tourism marketing strategy by empirically examining through structural equation modeling whether tourism storytelling affects lovemarks and could ultimately boost relationship strength.

The study equally bears vital managerial implications. First, DMO (Destination Marketing Organization) is developing tourism marketing communication in various countries to enhance the brand value of tourism destinations. The basis of these efforts is that many previous studies have consistently shown that there is positive impact of tourism marketing communications on tourism destinations. However, this study has shown that not only the brand value but also lovemarks affects relationship strength. Consequently, efforts should be made to form lovemarks. Second, uniqueness, interestingness and educability are found to be the main factors that improve the brand value of tourist destinations. Tourists can perceive brand value of a tourist destination differently according to the storytelling. Therefore, it is believed that brand value will improve if the unique story composition of each local tourist destination is well planned to stimulate interest as well as to include educational content. The object in the storytelling must be developed using various tangible and intangible resources that can attract unique impressions of a tourist destination especially for tourists. These include monuments, statues, myths, legends, old sayings, historical occurrences, celebrity trails and even imaginary objects. Third, visitors form lovemarks for tourist attractions through stories that stimulate sensibility. This suggests that the expertise of the tourism storyteller is very important. This also emphasizes that training storytellers at specialized institutions is needed and that various story compositions related to tourist attractions need to be planned. In addition, tourism destinations can be revitalized by actively utilizing digital storytelling, which has become a recent trend. Finally, the results of the current study show that a lovemarks of the tourist destination reinforces the relationship strength and the brand association of a tourist destination. This implies that if the relationship strength increases, the frequency of visits would be higher than that of other regions, and strong attachments can be formed. This underscores the value and usefulness of tourist destination storytelling. Therefore, the local government is required to implement lovemarks formation for tourist destinations in order to form strong and distinctive emotional consensus through tourist destination storytelling suitable for the region.

Despite the instructive findings, the study has limitations that can be addressed by future research. First, training of tourism storytellers is not being conducted through professional institutions. As a result, the lack of expertise related to tourist attractions can lead to confusion among tourists. In future research, it is necessary to provide a strategy to the expertise of such tourism storytelling. If a clear strategy is implemented, it is expected that the ripple effect will be great in developing the tourism industry. Second, in measuring relationship strength, the degree of attachment that tourists feel towards tourist attractions was expressed, yet the researchers faced a limitation to clearly grasp the measurement. In the marketing aspect, relationship strength is widely used to describe the extent to which consumers who purchase products or services perceive a specific brand, but there is a limit to measuring the degree of intimacy tourists feel about a specific tourist destination. Future studies can therefore develop and generalize a sophisticated measure of relationship strength. Third, in-depth research on digital storytelling should add value in the research field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.; methodology, M.J.; software, J.C.; validation, J.C. and M.J.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, M.J.; resources, M.J.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, J.K.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, J.K.; project administration, M.J.; funding acquisition, M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The paper was supported by the research grant of the University of Suwon in 2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Study’s constructs and their related items.

Table A1.

Study’s constructs and their related items.

| Construct | No | Question Instrument | Original Sentence | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interestingness | INT1 | It was interesting to hear about the tourist attraction. | It was interesting to hear about the tourist attraction. | Yang [41] Kim [42] Tilden [47] Kim [49] |

| INT2 | I wanted to go there after hearing the story of the tourist attraction. | I wanted to visit after hearing about the tourist destination. | ||

| INT3 | The story of this tourist attraction was exciting and touching. | The story of this tourist attraction was exciting and touching. | ||

| INT4 | I enjoyed listening to or watching stories about tourist attractions. | I enjoyed listening to or watching the story | ||

| Educability | EDU1 | The story of this tourist attraction is educational. | The tourist destination story was educational. | Yang [41] Kim [42] Kim [49] Ahn [50] |

| EDU2 | Through the story of tourist attractions, I was able to improve my understanding of the area I visited. | I was able to improve my understanding of the area I visited. | ||

| EDU3 | I was able to satisfy my intellectual needs through the story of tourist attractions. | Intellectual needs could be satisfied. | ||

| EDU4 | I got information about the tourist attraction through the story. | You can get tourist information. | ||

| Sensibility | SENS1 | Stories about tourist attractions gave dreams and abundant imagination. | The story gave dreams and rich imagination. | Yang [41] Kim [42] Ahn [50] |

| SENS2 | The story around the tourist destination has provoked curiosity. | The story aroused curiosity. | ||

| SENS3 | The story of the tourist attraction aroused emotion. | The story evoked emotions. | ||

| SENS4 | The story of the tourist attraction has memories and romance. | The story has memories and romance. | ||

| Descriptiveness | DES1 | The story of the tourist attraction was easy to understand. | The stories related to the tourist spots were easy to understand. | Yang [41] Kim [42] Kim [49] |

| DES2 | The story of the tourist attraction was described in detail. | The story of the tourist destination was described in detail. | ||

| DES3 | The story of the tourist destination was expressed realistically. | The story of the tourist destination was realistically expressed. | ||

| DES4 | The story of the tourist attraction was explained clearly and accurately. | The story was explained clearly and accurately. | ||

| Uniqueness | UNI1 | There is a story about a famous local figure in this tourist attraction. | Related to local people. | Yang [41] Moscardo [44] Kim [49] |

| UNI2 | There are legends, fairy tales and oral stories about this tourist attraction. | Local legends, fairy tales, and oral stories. | ||

| UNI3 | There is a story related to the history of this tourist attraction. | Stories related to the history of tourist destinations. | ||

| UNI4 | The story has a unique taste of tourist attraction. | The unique taste of tourist destinations. | ||

| Brand value | BV1 | Tourist attractions with storytelling are popular with many people. | This tourist destination is popular with people. | Yang [41] |

| BV2 | I prefer tourist attractions with storytelling. | I prefer this tourist destination. | ||

| BV3 | The tourist attractions with storytelling are very unique. | This tourist destination is very unique. | ||

| BV4 | It is worth visiting tourist attractions with storytelling. | Worth a visit to this tourist spot. | ||

| BV5 | I want to visit tourist attractions with storytelling even if it costs money. | I want to visit this tourist destination even if it costs money. | ||

| Lovemarks | LM1 | I could feel a novelty in this tourist spot. | I could feel the novelty. | Yang [41] |

| LM2 | This tourist attraction is rich in attractions. | Rich in attractions. | ||

| LM3 | I trust this tourist spot. | Trust this tourist destination. | ||

| LM4 | This tourist destination has a good image. | It has a good image. | ||

| LM5 | This tourist destination is known as an excellent tourist destination. | Known as an excellent tourist destination. | ||

| Relationship strength | RS1 | I feel affection for tourist attractions with storytelling. | I feel the affection for the tourist destination through storytelling. | Kim [63] |

| RS2 | I feel close to tourist attractions with storytelling. | I felt close to tourist destinations with storytelling. | ||

| RS3 | I feel psychologically close to tourist attractions with storytelling. | I felt psychological closeness to tourist destinations with storytelling. |

References

- UNWTO. A Practical Guide to Tourism Destination Management; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Molinillo, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Buhalis, D. DMO online platforms: Image and intention to visit. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G.; Alrawadieh, Z.; Dincer, M.Z.; Istanbullu Dincer, F.; Ioannides, D. Willingness to pay for tourist tax in destinations: Empirical evidence from Istanbul. Economies 2017, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornhorst, T.; Ritchie, J.B.; Sheehan, L. Determinants of tourism success for DMOs & destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders' perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 572–589. [Google Scholar]

- Hotels & Restaurant. 2021. Available online: http://hotelrestaurant.co.kr/mobile/article.html?no=9491 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Pachucki, C.; Grohs, R.; Scholl-Grissemann, U. No story without a storyteller: The impact of the storyteller as a narrative element in online destination marketing. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1703–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, S.M.A.; Hosany, S.; O'Brien, J. Storytelling in destination brands’ promotional videos. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stienmetz, J.; Kim, J.J.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Managing the structure of tourism experiences: Foundations for tourism design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, S.; Parra, C.; de Roo, G. Framing strategic storytelling in the context of transition management to stimulate tourism destination development. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Liu, C.-C. The effects of empathy and persuasion of storytelling via tourism micro-movies on travel willingness. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckins, J. Teaching Through the Art of Storytelling; Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- James, C.H.; Minnis, W.C. Organizational storytelling: It makes sense. Bus. Horiz. 2004, 47, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassano, C.; Barile, S.; Piciocchi, P.; Spohrer, J.C.; Iandolo, F.; Fisk, R. Storytelling about places: Tourism marketing in the digital age. Cities 2019, 87, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Xiang, Y.; Hutchinson, J. Local cuisines and destination marketing: Cases of three cities in Shandong, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.S. A study on effect of tourism storytelling of tourism destination brand value and tourist behavioral intentions. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.H.; You, E.S.; Lee, T.J.; Li, X. The influence of historical nostalgia on a heritage destination’s brand authenticity, brand attachment, and brand equity. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganassali, S.; Matysiewicz, J. Echoing the golden legends: Storytelling archetypes and their impact on brand perceived value. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 437–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A.B. Getting Carried Away: Understanding Memory and Consumer Processing of Perceived Storytelling in Advertisements. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.Y. A Study on the Effect of Wine Storytelling on Brand Recognition and Purchase Behavior. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.H.; Chen, C.-H.S.; Lee, T.J. Interaction between the individual cultural values and the cognitive and social processes of global restaurant brand equity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 64, 102847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K. The Lovemarks Effect: Winning in the Consumer Revolution; Power House Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, S.; Roth, M.S.; Madden, T.J.; Hudson, R. The effects of social media on emotions, brand relationship quality, and word of mouth: An empirical study of music festival attendees. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawle, J.; Cooper, P. Measuring emotion: Lovemarks, the future beyond brands. J. Advert. Res. 2006, 46, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Back, K.J. Influence of brand relationship on customer attitude toward integrated resort brands: A cognitive, affective, and conative perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Dey, B.L.; Yalkin, C.; Sivarajah, U.; Punjaisri, K.; Huang, Y.A.; Yen, D.A. Millennial Chinese consumers' perceived destination brand value. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, S.; Rita, P. Brand strategies in social media in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Ryu, K.; Hussain, K. Influence of experiences on memories, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: A study of creative tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Song, M.K.; Shim, C. Storytelling by medical tourism agents and its effect on trust and behavioral intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.Y.S.; Busser, J.; Baloglu, S. A model of memorable tourism experience: The effects on satisfaction, affective commitment, and storytelling. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, Q. Examining structural relationships among night tourism experience, lovemarks, brand satisfaction, and brand loyalty on “cultural heritage night” in South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Seo, G.D. A study on relationship among Lovemarks, Brand Identification, Brand Equity & Behavior Intention. J. Digit. Converg. 2017, 15, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, G.D.; Lee, J.E. A study on the structural relationship between resource attraction, entertainment experience, lovemark and attachment in tourist destination. J. Digit. Converg. 2022, 20, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, J.D. Homo Narrans; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, K.; Leicht, T.; Marongiu, L. Storytelling in the context of destination marketing: An analysis of conceptualizations and impact measurement. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howison, S.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Sun, Z. Storytelling in tourism: Chinese visitors and Māori hosts in New Zealand. Anatolia 2017, 28, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G. Market-Driven Thinking: Achieving Contextual Intelligence; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN-13 978-0750679015. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Tourism Organization. Why Is It Tourism Storytelling? Korea Tourism Organization Press: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Wall, G. Social media, space and leisure in small cities. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.I. A Study on the Effects of Tourist’s Storytelling Experience on the Awareness of the Brand Value and Lovemarks for Tourism Destination-Focusing on The Control Effects of Mindfulness. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J. Study on the Effect of Attributes of Tourism Storytelling for the Perception of Destination Attractiveness, Brand Equity and Brand Value. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School, Dong-A University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, B.C.; Jang, S.; Kim, Y.; Park, S. A Preliminary Survey on Story Interestingness: Focusing on Cognitive and Emotional Interest. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. Mindful visitors: Heritage and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 376–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.I.; In, O.N.; Lee, T.H. Tourists expectation of destination lovemark from tourism storytelling. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2010, 34, 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, G.W. Interpreting the Environment; John Willy & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tilden, F. Interpreting Our Heritage; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; Yanning, Z.; Huimin, G.; Song, L. Tourism, a classic novel, and television: The case of cao xueqin’s dream of the red mansions and grand view gardens, Beijing. Beijing J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J. A Study on the Effect of Storytelling Attributes of Cultural Tourism Resources for Tourists Satisfaction. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Tourism, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Y.J. The Relationships of Cultural Attraction Attributes, Interpretation, and Tourist Satisfaction. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Business Administration, Dong-A University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, G.; Pachal, Z.M. Examining the effect of brand equity dimensions on domestic tourists’ length of stay in Sareyn: The mediating role of brand equity. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kandampully, J. The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer-brand relationships. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2012, 21, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.; Crane, F.G. Building the service brand by creating and managing an emotional brand experience. J. Brand Manag. 2007, 14, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E. Development of a Brand Image Scale and the Impact of Lovemarks on Brand Equity. Doctoral Dissertation, Unpublished Thesis Graduate School of the Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, S.D.; Maxian, W.; Laubacher, T.C.; Baker, M. In search of Lovemarks: The semantic structure of brands. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Advertising, Eugene, OR, USA, 2007; pp. 42–49. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/fdeb40b603275dbbe93b677135d1bfc6/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=40231 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Bove, L.L.; Johnson, L.W. A customer-service worker relationship model. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000, 11, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, B.; O’toole, T. Classifying relationship structures: Relationship strength in industrial markets. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2000, 15, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, A. Variations in relationship strength and its impact on performance and satisfaction in business relationships. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2001, 16, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, K.; Money, R.B.; Sharma, S. National culture and industrial buyer-seller relationships in the United States and Latin America. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L.; Johnson, L.W. Customer relationships with service personnel: Do we measure closeness, quality or strength? J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. The relationship between positive psychology and tourist behavior studies. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. Effect relationship among brand congruity, lovemarks, and relationship continuity intention in tourism destination. Inter. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 30, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.I.; Lee, J.H.; Won, C.S.; Park, D.H.; Oh, C.H. A study on tourism storytelling and strength of relationship of visitor's in Busan: The mediating role of lovemark. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2011, 35, 279–297. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.H. Evaluation of brand equity of tourism destinations in Korea. J. Tour. Sci. 2001, 25, 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. The value of brand equity. J. Bus. Strategy 1992, 13, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, W.; Lichtenstein, E. Stories are to entertain: A structural-affect theory of stories. J. Pragmat. 1982, 6, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand effect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Clark, M.K.; Hammedi, W.; Arvola, R. Cocreated brand value: Theoretical model and propositions. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation model with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, K. Tourism destination marketing–A tool for destination management? A case study from Nelson/Tasman Region, New Zealand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 10, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).