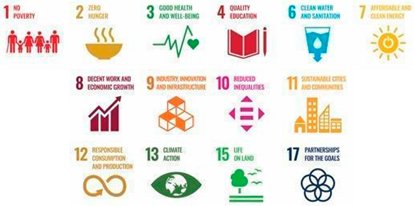

Declaration of the Sustainable Development Goals of Mining Companies and the Effect of Their Activities in Selected Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. SDGs and Reporting Standards (GRI, SASB)

- Inside-out and outside-in double materiality, aiming to provide reliable and relevant data presenting an integrated view of the company (financial and non-financial data);

- The improvement in the quality of the reported information and its better alignment with investor expectations;

- Definition of reporting requirements towards the realistic implementation of processes and measuring and improving ESG and decarbonization performance (act not talk);

- ESG reporting needs and taxonomy disclosures;

- ESG risks and opportunities arising from the sector of activity;

- Redirection of the financial capital to support low-carbon investments, projects, businesses, and areas of the economy;

- Integration of the financial reporting, climate risks and opportunities, and promotion of transparency;

- The possibility to compare companies’ ESG disclosures and actions, across sectors, within a country or market, etc., moving away from the current freedom to choose standards;

- Changes in terminology: the current trend is to report sustainable development (ESG) information rather than non-financial data; the terms purpose-oriented, mission-driven company, regenerative company, net-positive, climate-resilient company, and stakeholder-oriented appear instead of a socially responsible company (CSR);

- Scope S (human rights policy, human rights due to diligence procedures, diversity among supervisory board, equal pay index, job rotation, freedom of association, and collective bargaining);

- Scope E (greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, climate risks and opportunities);

- Scope G (board structure, code of ethics, anti-corruption policy, whistleblowing mechanism).

- Areas that may be relevant to the mining sector are:

- Scope S (occupational health and safety);

- Scope E (intensity of greenhouse gas emissions, emissions management, water consumption and management, impact on biodiversity, waste management).

3. Results Reporting on SD Goals in Industry Entities

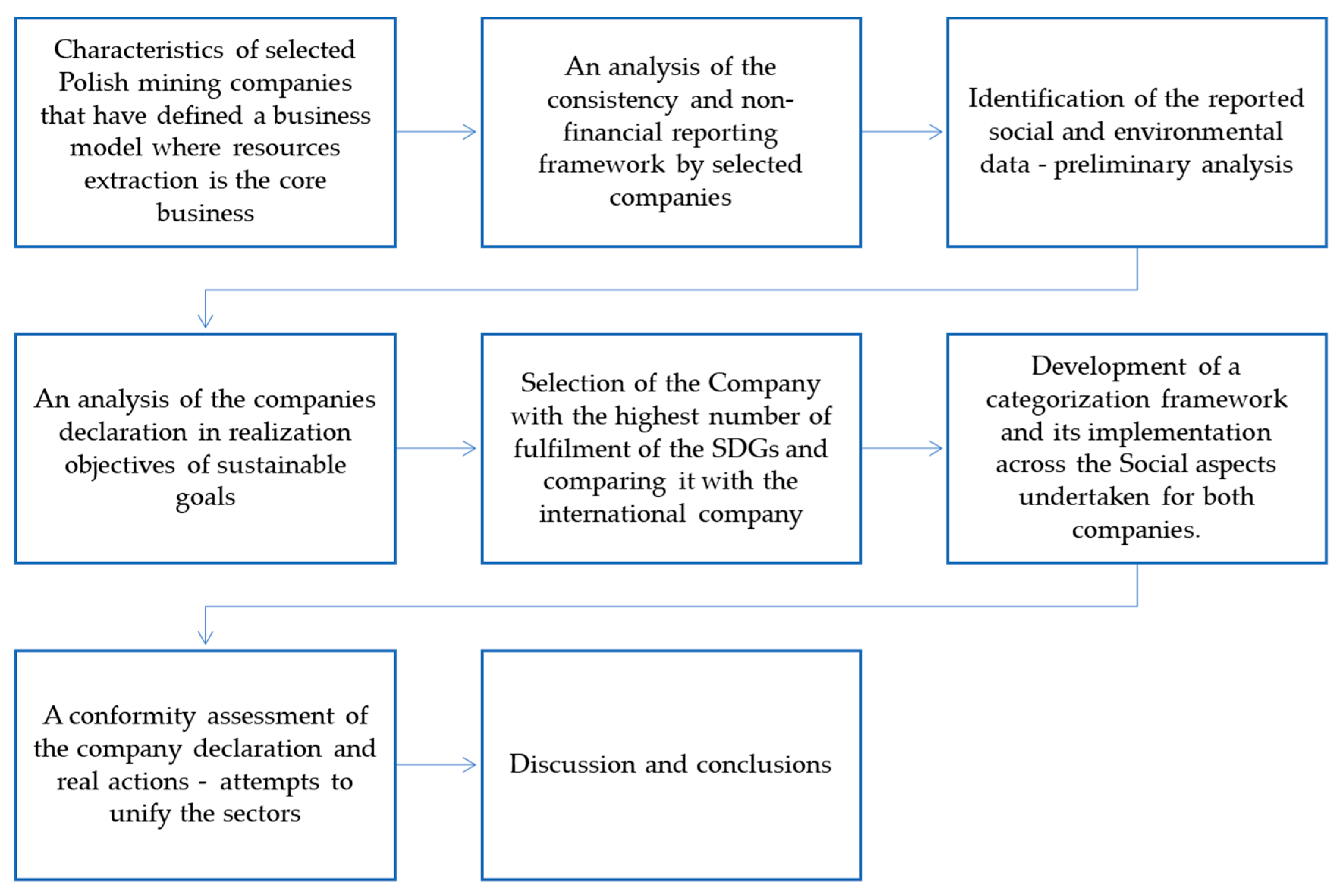

4. Research Methodology

5. Data

6. Results

7. Summary and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Detailed Description of the Categorization Framework

| Companies | JSW/KGHM/LW Bogdanka (2017–2020) | |

|---|---|---|

| Aspects | Category | |

| S * | Diversity | Including women and different age groups in the overall workforce, particularly emphasizing the number and role of women on management and boards of directors. |

| Human Rights | The analyzed companies emphasize the deep conviction that every person has an inalienable dignity, which gives him a number of rights. At the same time, all entities declare not to accept any form of differentiation or discrimination between persons, and consequently to provide equal opportunities to all employees and persons associated with the entities regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political opinion, social origin, wealth or other differences. The actions undertaken in the direction of human rights are confirmed by the codes of conduct and ethics created by the entity (KGHM, JSW) as well as training courses for employees, including management staff in the area of human rights (JSW, KGHM, LW Bogdanka). | |

| Initiatives for employees and local communities | Social assistance to employees, their families, and the local community, funding health promotion programs and providing grants to medical institutions. The entities also implement social initiatives through scholarships for talented youth. | |

| Anti-corruption initiatives | Creating anti-corruption systems, such as the Compliance System, which includes the Anti-Corruption Policy (JSW), Anti-corruption Programs (KGHM) or training on anti-corruption policies and procedures (LW Bogdanka). | |

| Consideration of social issues at the stage of liquidation (related to stage, consequences, company license) | Analyzing the consideration of social issues at the stage of liquidation (related to stage, consequences, company license) in the period 2017–2020, such action was declared (in the analyzed reports) only by LW Bogdanka. This primarily involved social security, raising the funds from the Fair Transition Fund for the region, and working with regional authorities and organizations to find new jobs after the mine closure. | |

| E ** | Environmental management system | During the four years of their operations, the entities implemented and used the ISO 14001:2015 environmental management system |

| Energy Use Reporting Manufacturing from RES | Reporting of energy consumption in MWh or GWh. However, energy production from RES has been declared and reported by KGHM and LW Bogdanka (since 2018). | |

| Water consumption reporting (water and sewage | The entities include in their reports the use of water for consumption and technological and production purposes. Additionally, they report the amount of wastewater produced. | |

| Records of CO2, SOx, NOx emissions and other | Records of gas emissions are kept, but their recording over the analyzed four years was not consistent. The amount and type of emitted gases changed in individual years. It should be noted that JSW has included gas emissions in its reports from 2018. | |

| Waste managements | Records of generated waste, both municipal and those resulting from technological processes, e.g., waste rock. | |

| Investments of RES | In 2018, LW Bogdanka started investing in RES by producing components for renewable energy installations and recycling photovoltaic waste. Over the analyzed years, KGHM has also increased the production of energy from its own sources (including RES), mainly by investing in photovoltaics. JSW declares to invest only in solar farms. | |

| Biodiversity | Actions to protect local biodiversity and rehabilitate the areas that have undergone transformation. In addition, all mining companies run the so-called environmental monitoring. | |

| Circular Economy/ECO | JSW focused mainly on projects related to the possibility of using hydrogen extracted from coke oven gas for the development of clean technologies (Hydrogen Project) and the use of methane, which is a by-product of the mine’s operations—for the production of carbon nanotubes (Carbon nanostructures—CNT). The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the idea of using salt (sodium chloride) from mine waters to produce ZODOX, which is bactericidal, virucidal, and fungicidal. In the CE/ECO projects, LW Bogdanka focused on the use of underground water for technological purposes, as well as powering the fire protection and air-conditioning installations on the surface. In addition, the company regenerates roof supports, which, instead of being scrapped, may become a full-value element and be reused. LW Bogdanka S.A., together with representatives of the world of business and science from various countries, joined in 2020 a research project consisting in developing new ways of mining waste management (MINRESCUE—From Mining Waste to Valuable Resource: New Concepts for Circular Economy). One of the symptoms of the circular economy in KGHM is the production of road aggregates from copper slag, which is a by-product of the production process in steel mills. Annually, it is about 650–700 thousand tons of mastic slag and about 450 thousand tons of granulated slag, whose recipients are the largest companies specializing in road construction. | |

| Considerations of environmental issues on the liquidation stage | In 2017–2020, both JSW, KGHM, and LW Bogdanka published information indicating that environmental problems were considered at the stage of liquidation of the enterprise or the phasing out of individual exploitation fields. Nevertheless, entities do not provide (do not define) individual problems and ways of solving them. Each of the analyzed mining entities has emphasized the importance of removing and compensating mining damages (e.g., reclamation) at every stage of its operations. | |

Appendix B. Detailed Description of the First, Third and Fifth Sustainable Development Goals

| The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | Company | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGHM Polska Miedź S.A. | ||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| The KGHM Foundation has been conducting charity activities associated with various social issues since 2003. Among other things, social assistance includes helping families and individuals in difficult situations and ensuring equal opportunities. The Foundation provides financial and material donations both to institutions for the implementation of projects and to individuals in the field of health care as well as aid to victims of natural disasters and catastrophes. | |||

| The fulfillment of 1 SDGs: employment of local residents; development strategy for municipalities in which the Company operates, numerous social agreements raising the standard of living of the Zagłębie Miedziowe region inhabitants; elimination of poverty and hunger; aid to victims of calamities and natural disasters, aid to repatriants. | ||||

| Realization The available list of donations transferred by the Foundation to its charges in 2017 indicate that: financial support was granted to, among others, people dealing with difficult situations in their lives and victims of natural disaster. Through the help of KGHM Polska Miedź S.A., in 2017 five families from Kazakhstan “found their home in Poland”. The Company offered the repatriates employment, assistance in finding accommodation, learning the Polish language, daily support in adapting to Polish conditions, and the working environment in the KGHM Group. | Realization In 2018, the KGHM Polska Miedź Foundation granted support in the form of cash donations, inter alia, for the purchase of equipment for the Nursing Home in order to improve the quality and standard of living of its residents; co-finance for the program “Providing meals to those deprived of food”; organization of recreation for children from poor families at risk of social exclusion. | Realization Funds granted in 2019 by the Foundation were transferred, among others, to subsidize activities to support lonely people and families in need; to provide meals, food, hygiene products to poor people and those in difficult life situations from the city of Lubin and its surroundings; to subsidize financial aid and Christmas packages to people in need. | Realization Over 34 thousand employees, most of whom come from the Copper Belt area. In 2020, the KGHM Polska Miedź Foundation granted support in the form of cash and material donations. The donations included, among others, activities related to charitable assistance for civilians in refugee camps on the island of Lesbos; financial aid to organizations for the homeless or meals’ provision to people in difficult living conditions. | |

| Over the years, the Company has had one constant objective to support the health and safety of both employees, their families, and residents across the region. The Company achieves this through the operation of the Copper Health Center, health-oriented programmes, as well as donations made to medical centers and individuals as part of the KGHM Polska Miedź Foundation. Individuals receive financial support from the KGHM Polska Miedź Foundation for health care, mainly for the purchase of hearing aids and wheelchairs, medications, surgical treatment, including treatment abroad, and stationary rehabilitation. | |||

| The fulfillment of 3 SDGs: support for health and safety; health promotion; co-financing of pro-health prevention programs; counteracting the exclusion of disabled persons; co-financing of rehabilitation holidays and surgical treatments; purchase of hearing aids and wheelchairs; rescue and civil protection; | ||||

| Realization Transfer of foundation funds, among others, for specialized and modern medical equipment purchase, rehabilitation equipment; subsidies for the purchase of medicines and medical visits; subsidies for the construction of infrastructure for the disabled. | Realization In 2018, the financial support included, among others, financing preventive examinations for residents; blood donation projects and subsidies for rehabilitation holidays. Hearing aids for 26 people, wheelchairs, insulin pumps, prosthetic limbs, were also purchased; rehabilitation was provided to disabled people and medical expenses were covered for 35 people. Under the “Health Promotion and Environmental Risk Prevention Program,” five projects were funded for preventive health tours for 259 children. | Realization In 2019, the funds provided by the KGHM Polska Miedź Foundation supported the construction of a rehabilitation and education center; they contributed to preventing the exclusion of people with disabilities and allowed the purchase of specialist medical and rehabilitation equipment. Under the “Health Promotion and Environmental Risk Prevention Program”, nine projects were funded for preventive health tours for 616 children. | Realization In 2020, financial support from the KGHM Polska Miedź Foundation was provided for such expenses as the purchase of hearing aids and wheelchairs, medicines; surgical treatment, including treatment abroad; and inpatient rehabilitation. In addition, due to the epidemiological situation related to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, in-kind donations of COVID-19 countermeasures were made to 134 institutions. Under the “Program for Health Promotion and Counteracting Environmental Risks” a project concerning preventive-health tours for 49 children was funded. | |

| A Code of Ethics operates in the entire KGHM Group, specifying a set of principles binding on all employees, entities belonging to the KGHM Group and cooperating entities. The Code relates to preventing the abuse of employee rights, including discrimination and mobbing. | |||

| The fulfillment of five SDGs: the principles of equal opportunities among employees; employee diversity; ensuring a work environment free from discrimination and harassment; compliance with human rights standards with respect to working time or minimum wage; diversity management (also applies to members of the Supervisory Board and Management Board of KGHM Polska Miedź S.A., management and supervisory staff consists of people of different gender, age and experience). | ||||

| Realization The existing structure of gender diversity in the workforce. The total number of employees in 2017 was 18,198, of which 1307 were women and 17,046 were men. Additionally, 1 304 women and 17,039 men had full-time contracts. By duration of employment, there were 1221 women and 15,499 men on permanent contracts. | Realization The existing structure of gender diversity in the workforce. There are no data about the total number of women employed. | Realization The existing structure of gender diversity in the workforce. There are no data about the total number of women employed. | Realization The existing structure of gender diversity in the workforce. There are no data about the total number of women employed. | |

| Barrick Gold | ||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| The fulfillment of one SDGs: contributing to the development of local communities by local purchasing and local employment, increasing participation among local people’s employees, sharing the benefits of business operations with local communities, increasing access to health-related services, education and water | |||

| In 2017, Barrick employed over 10,000 employees, including: 60% local workers, 27% Canadian workers (national) 9% regional employees, 3% other nationalities. A total of 44% of 2017 revenue—USD 1,118,500,000 was spent on taxes and royalties, which helped governments to finance community programs and support society. A total of USD 23,410,000 allocated to local community investment. A total of USD 351,300,000 allocated to local purchases. | A total of 7.48 billion was donated to employees, governments, suppliers, and local communities by the legacy companies. A total of 1.07 billion allocated in the form of taxes and other payments to governments in the countries where they operate. A total of 37,158,000 USD allocated to local community development. A total of 7806 employees from local communities. | A total of USD 1,322,390,000 donated in the form of taxes and other payments to governments in the countries where they operate. A total of USD 25,538,000 donated to the development of the local communities (education, food, health, water, and local economic development). | A total of USD 26.5 mln was spent on the development of local communities. A total of USD 1.9 mln in produce bought from local producers. A total of 4.5 billion spent with host country suppliers. Economic Stymulus Programs—I-80 Fund in Nevada related to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was created to support small and medium-sized enterprises that will need exceptionally large support during and after the pandemic. A total of 11,691 employees from local communities. | |

| No data | The fulfillment of three SDGs: taking care of the well-being of employees, their families, and local communities | ||

| More than USD 1.2 mln allocated to community health programs. Malaria incidence rates in the AME (Africa and Middle East) region fell from 24.6% to 20.4% among employees. This is all thanks to independent anti-malaria campaigns. | A total of USD 690,000 donated to anti-malaria initiatives. A total of 570,000 condoms were bought for workers and local people in Sub-Saharan areas where Barrick has mine sites. Barrick Clinics offered over 16,000 free VCTs (Voluntary Counseling and Testing). A total of 100% of employees under the health and safety programs. | More than USD 30 mln in COVID-19 support provided to the host countries and communities Barrick provided 11,833 HIV tests and counseling. A total of 5906 consultations for local communities conducted in mining clinics in Africa and the Middle East. A 6.3% reduction in malaria cases among workers compared to 2019. 100% employees under the occupational health and safety programs | ||

| No data | The fulfillment of three SDGs: playing an important role to redress inequality—particularly in the mining industry through recruitment and development policies which are designed to ensure that employees have opportunities for growth and can become the best of the best—regardless of gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation or religious belief. | ||

| A total of 1885 employed women. All female employees have equal earnings opportunities as male employees In Peru, workshops and programs were organized near the Pierina mine to strengthen leadership skills for over 100 local women. Any form of discrimination is prohibited under the Code of Business Conduct and Ethics, and the Human Right Policy. Of the 9 people on the Barrick board, 1 is female. Barrick Gold has a zero tolerance for harassment. | Over 3600 private security personnel and 1200 public security personnel were trained in security and human rights. A total of 10 women in the Dominican Republic were elected as Gender Ambassadors. A total of 15% of all Senior Management are women. A total of 10% of all employees are women. | A total of 10% of all employees are women. Greenfield Talent Program (The program provides high potential college graduates with up to three years’ work experience with technical experience across the mine)—27% of participants in this program were women. Organizing a career workshop for 37 Nevada-based women led by Barrick’s HR department They have set a goal by 2022 for women to account for 30% of the board. | ||

References

- Bose, S. Evolution of ESG Reporting Frameworks. In Values at Work; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups Text with EEA Relevance. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/95/oj (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting, COM/2021/189 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0189 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- GPW. 2021. Available online: https://www.gpw.pl/pub/GPW/ESG/Wytyczne_do_raportowania_ESG.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Stanek-Kowalczyk, A. Raportowanie Niefinansowe/Raportowanie Zrównoważonego Rozwoju w świetle Standardów Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu Oraz Zmieniających Się Regulacji UE, Webinar Presentation, Aktualne Trendy W rozwoju Standardów Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/wydarzenia-csr (accessed on 12 May 2022). (In Polish)

- Rok, B. Odpowiedzialny Biznes w XXI Wieku. Trendy Regulacyjne a Trendy Rynkowe, Webinar Presentation, Aktualne Trendy w Rozwoju Standardów Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Available online: https://psw.kwidzyn.edu.pl/images/news/20.05.2022/Webinarium_GR_ds_SOU_12_05_2022.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2022). (In Polish).

- Deloitte. 2022. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- SASB. Available online: https://www.sasb.org/company-use/sasb-reporters/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- GRI. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Tóth, Á.; Suta, A.; Szauter, F. Interrelation between the climate-related sustainability and the financial reporting disclosures of the European automotive industry. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. The Evolution of ESG and Disclosures. Social Issues Now Take Centre Stage Roopa Davé, Partner, Sustainability and Impact Services, KPMG in Canada. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/ca/pdf/2020/11/the-evolution-of-esg-and-disclosures-roopa-dave.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Deloitte. The 2030 Decarbonization Challenge The Path to the Future of Energy. 2021. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/deloitte/global/Documents/Energy-and-Resources/gx-eri-decarbonization-report.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Deloitte. Tracking the 2021 Mining Industry Trends|Deloitte Insights. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/mining-and-metals/tracking-the-trends.html (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Zharfpeykan, R. Representative account or greenwashing. Voluntary sustainability reports in Australia’s mining/metals and financial services industries. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2209–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, S.J. Framing fracking: Scale-shifting and greenwashing risk in the oil and gas industry. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1311–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Seele, P.; Rademacher, L. Grey zone in—Greenwash out. A review of greenwashing research and implications for the voluntary-mandatory transition of CSR. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimonenko, T.; Bilan, Y.; Horák, J.; Starchenko, L.; Gajda, W. Green Brand of Companies and Greenwashing under Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, W.; Ferreira, P.; Araújo, M. Challenges and pathways for Brazilian mining sustainability. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, R.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Ali, S.M.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Karuppiah, K. Assessment of key socio-economic and environmental challenges in the mining industry: Implications for resource policies in emerging economies. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashan, A.J.; Lay, J.; Wiewiora, A.; Bradley, L. The innovation process in mining: Integrating insights from innovation and change management. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, M.R.; Dzombak, D.A. A review of sustainable mining and resource management: Transitioning from the life cycle of the mine to the life cycle of the mineral. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrobelli, C.; Marin, A.; Olivari, J. Innovation in mining value chains: New evidence from Latin America. Resour. Policy 2018, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Innovation and technology for sustainable mining activity: A worldwide research assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, N.B.R.; da Silva, E.A.; Neto, J.M.M. Sustainable development goals in mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J. Mining companies and communities: Collaborative approaches to reduce social risk and advance sustainable development. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Alves, M.-C.; Silva, R.; Oliveira, C. Mapping the Literature on Social Responsibility and Stakeholders’ Pressures in the Mining Industry. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Mendes, L. Mapping of the literature on social responsibility in the mining industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hąbek, P.; Biały, W.; Livenskaya, G. Stakeholder engagement in corporate social responsibility reporting. The case of mining companies. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2019, 24, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Famiyeh, S.; Opoku, R.A.; Kwarteng, A.; Asante-Darko, D. Driving forces of sustainability in the mining industry: Evidence from a developing country. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenda 2030, 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Endl, A.; Tost, M.; Hitch, M.; Moser, P.; Feiel, S. Europe’s mining innovation trends and their contribution to the sustainable development goals: Blind spots and strong points. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Yim, D.; Khuntia, J. Online Sustainability Reporting and Firm Performance: Lessons Learned from Text Mining. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivic, A.; Saviolidis, N.M.; Johannsdottir, L. Drivers of sustainability practices and contributions to sustainable development evident in sustainability reports of European mining companies. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Urbieta, L.; Boiral, O. Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: From cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RMF and CConSI, 2020 Responsible Mining Foundation and Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment 2020. ‘Mining and the SDGs: A 2020 status update’. Available online: https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/d8-9h2r-rj13/download (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Forestier, O.; Kim, R.E. Cherry-pickingthe Sustainable Development Goals: Goal prioritization by national governments and implications for global governance. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.; Sanchez, L.E. Assessing the Evolution of Sustainability Reporting in the Mining Sector. Environ. Manag. 2019, 43, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saka, C.; Oshika, T. Disclosure effects, carbon emissions and corporate value. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A. The role of sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs) in implementing sustainable strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pactwa, K. Scope of Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals by the Mining Sector in Poland; Mining and Geology Wrocław University of Science and Technology: Wrocław, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bogusz, K.; Sulich, A. The Sustainable Development Strategies in Mining Industry. Educ. Excell. Innov. Manag. Vis. 2020, 6893–6911. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333949551_The_Sustainable_Development_Strategies_in_the_Mining_Industry (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Pactwa, K.; Woźniak, J.; Strempski, A. Sustainable mining–Challenge of Polish mines. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janikowska, O.; Kulczycka, J. Impact of minerals policy on sustainable development of mining sector–a comparative assessment of selected EU countries. Miner. Econ. 2021, 34, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamjahdi, A.; Bouloiz, H.; Gallab, M. Overall performance indicators for sustainability assessment and management in mining industry. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Optimization and Applications, (ICOA), Wolfenbüttel, Germany, 19–20 May 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Izzo, M.F.; Ciaburri, M.; Tiscini, R. The Challenge of Sustainable Development Goal Reporting: The First Evidence from Italian Listed Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pactwa, K.; Woźniak, J. Environmental reporting policy of the mining industry leaders in Poland. Resour. Policy 2017, 53, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, J. The Role and Implementation of the Concept of Social Responsibility in the Functioning of Mining and Energy Industry; Wrocław University of Science and Technology: Wrocław, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pactwa, K. Achieving United Nations sustainable development goals by the mining sector—A Polish example. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. Miner. Resour. Manag. 2021, 37, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JSW. 2022. Available online: https://www.jsw.pl/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- KGHM. 2022. Available online: https://www.kghm.com/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- LW Bogdanka. 2022. Available online: https://www.lw.com.pl/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Barrick Gold. 2022. Available online: https://www.barrick.com (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- PARP. 2021. Available online: https://www.parp.gov.pl/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Woźniak, J. Corporate vs. Corporate foundation as a support tool in the area of social responsibility strategy–Polish mining case. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal of Laws of 1992, No. 21, Item 86 (Art. 17 of the Act of February 15, 1992 on Corporate Income Tax). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19920210086 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Journal of Laws of 2016, Item 40 (Act of April 6, 1984 on Foundations). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19840210097 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Journal of Laws of 2003, No. 96, item 873 (Act of April 24, 2003 on Public Benefit and Volunteer Work). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20030960873 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Statute of the KGHM Foundation. Available online: http://fundacjakghm.pl/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Pactwa, K. Is There a Place for Women in the Polish Mines?—Selected Issues in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, L. Bordering on Equality: Women Miners in North America. Gendering the Field Towards Sustainable Livelihoods for Mining Communities. In Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph; Lahiri-Dutt, K., Ed.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2011; Volume 6, pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter, J. Experiences of Indigenous Women in the Australian Mining Industry. Gendering the Field towards Sustainable Livelihoods for Mining Communities. In Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph; Lahiri-Dutt, K., Ed.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2011; Volume 6, pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kansake, B.A.; Sakyi-Addo, G.B.; Dumakor-Dupey, N.K. Creating a gender-inclusive mining industry: Uncovering the challenges of female mining stakeholders. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.C.; Zorigt, D. Managing occupational health and safety in the mining industry. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 16, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, E.J.; Goggins, K.A.; Pegoraro, A.L.; Dorman, S.C.; Pakalnis, V.; Eger, T.R. Safety Culture: A Retrospective Analysis of Occupational Health and Safety Mining Reports. Safe Health Work 2020, 12, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimpa, N.; Nunkoo, R. How mining companies promote gender equality through sustainable development? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1647590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Ali, M.; French, E. Effectiveness of gender equality initiatives in project-based organizations in Australia. Aust. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perks, R.; Schulz, K. Gender in oil, gas and mining: An overview of the global state-of-play. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company | Form of Operation (Capital Group/ Parent Company) | Range of Activity (Global/ Domestic/Local) | Type of Raw Material | Other Operations | Communication Channels (pdf, www Report) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSW | Capital group | Mining in Poland Global sale | Hard coking coal, coke | Treatment of coking coal, coke, and coal derivatives | www.jsw.pl (accessed on 30 May 2022) Social media (LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube) |

| KGHM | Capital group | Global | Copper/Noble metals/Rhenium/Molybdenum/Nickel/Palladium | Metallurgy and Refining, Processing | kghm.com (accessed on 30 May 2022)/ Social media (accessed on 30 May 2022) (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter) |

| LW Bogdanka | Capital group | Domestic, located in eastern and west-eastern Poland | Hard coal | Energetics Repair of machines and instruments | www.lw.com.pl (accessed on 30 May 2022)/ Communication channel (.pdf, www report, Facebook) |

| Year | Disclosing Non-Financial Information | Type of Report | ISO 2600 or Other Guidelines | Tools Used for Reporting Social Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSW | ||||

| 2017 | Pdf report available on jsw.pl (accessed on 30 May 2022) | Sustainable | Yes | GRI Standards |

| 2018 | ||||

| 2019 | ||||

| 2020 | ||||

| KGHM | ||||

| 2017 | Pdf report available at kghm.com (accessed on 30 May 2022) | Integrated | Yes | GRI Standards |

| 2018 | Sustainable | |||

| 2019 | Integrated | |||

| 2020 | Integrated | |||

| LW Bogdanka | ||||

| 2017 | Pdf report available at ri.lw.com.pl (accessed on 30 May 2022) | Integrated | Yes | GRI standards |

| 2018 | Integrated | |||

| 2019 | Management and integrated report | |||

| 2020 | Integrated | |||

| Companies | JSW | KGHM | LW Bogdanka | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect | Category | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| S * | Diversity (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| Human Rights (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Initiatives for employees (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Initiatives for the local community (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Anti-corruption initiatives | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Consideration of social issues at the stage of liquidation (related to stage, consequences, company license) (Y/N) | N | N | Y | ||||||||||

| E ** | Environmental management system (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| Energy Use Reporting (Y/N) Manufacturing from RES (Y/N) | Y, N | Y, Y | Y, N | Y, Y | |||||||||

| Water consumption reporting (water and sewage) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Records of CO2, SOx, NOx emissions and other | No data | CO2, HFCs, CO, CH4, SOx, NOx | CO2, SOx, NOx | CO2 | CO2 SO2 | CO2, SO2, NO2 | CO2, C2OH12, CO, SO2, NxOy | ||||||

| Waste managements (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Investments of RES (Y/N) | No data | Y | Y | No data | Y | ||||||||

| Biodiversity (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| CE/ECO (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Considerations of environmental issues on the liquidation stage (Y/N) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Company |  |

|---|---|

| JSW |  |

| KGHM |  |

| LW Bogdanka |  |

| Company | Range of Activity | Number of Employees (2020) | Type of Raw Material | Copper Production in 2020 (kt) | Silver Production in 2020 (t) | Gold and Other Precious Metals (TPM) Production in 2020 (t) | Sustainability Reporting | Tools Used for Reporting Social Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGHM Capital Group (KGHM Polska Miedź S.A.) | global (domestic) | 34,116 (18,440) | copper ore, silver, lead, gold, electrolytic copper | 709.2 (392.7) | 1350.5 (1218.2) | 6.04 (3.01) | since 2011 | GRI Standards |

| Barrick Gold | global | 22,600 | gold, silver, copper | 207.3 | No data | 148.75 | since 2008 | GRI Standards and SASB Standards |

| Year | Financing Area | KGHM Polska Miedź S.A. | Barrick Gold | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financing Amount (USD) * | Total Annual Revenue (USD) * | The Share of Expenses in Financing Individual Areas in Relation to the Revenue (%) | Financing Amount (USD) * | Total Annual Revenue (USD) * | The Share of Expenses in Financing Individual Areas in Relation to the Revenue (%) | ||

| 2017 | Health and safety | 140,863.82 | 0.04 | 1,420,000.00 | 0.02 | ||

| Science and education | 518,196.45 | 0.01 | 6,330,000.00 | 0.08 | |||

| Sport, recreation, culture and tradition | 7,392,919.21 | 0.20 | 2,160,000.00 | 0.03 | |||

| Total | 9,319,755.49 | 3,621,202,020.32 | 0.26 | 9,910,000.00 | 8,374,000,000.00 | 0.12 | |

| 2018 | Health and safety | 1,291,540.36 | 0.04 | 1,338,000.00 | 0.02 | ||

| Science and education | 98,239.16 | 0.03 | 8,887,000.00 | 0.12 | |||

| Sport, recreation, culture and tradition | 9,063,903.97 | 0.25 | 7,454,000.00 | 0.10 | |||

| Total | 11,336,683.48 | 3,560,863,719.05 | 0.32 | 17,679,000.00 | 7,243,000,000.00 | 0.24 | |

| 2019 | Health and safety | 1,340,853.36 | 0.03 | 1,400,000.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Science and education | 955,544.81 | 0.02 | 6,100,000.00 | 0.06 | |||

| Sport, recreation, culture and tradition | 9,798,112.61 | 0.25 | 8,300,000.00 | 0.09 | |||

| Total | 12,094,510.79 | 3,996,113,038.27 | 0.30 | 15,800,000.00 | 9,717,000,000.00 | 0.16 | |

| 2020 | Health and safety | 2,613,624.19 | 0.06 | 2,900,000.00 | 0.02 | ||

| Science and education | 1,125,032.97 | 0.03 | 6,800,000.00 | 0.05 | |||

| Sport, recreation, culture and tradition | 10,280,618.03 | 0.24 | 500,000.00 | 0.004 | |||

| Total | 1,401,275.19 | 4,367,408,277.87 | 0.32 | 10,200,000.00 | 12,595,000,000.00 | 0.08 | |

| Year | KGHM Polska Miedź S.A. | Barrick Gold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation of Women on Board of Directors and Executive Committee (%) | Employment of Women (%) | Participation of Women on Board of Directors and Executive Committee (%) | Employment of Women (Workforce) (%) | |

| 2017 | 7.14 | 7.18 | 20.83 | No data |

| 2018 | 13.33 | No data | 12.00 | 9.65 |

| 2019 | 13.33 | No data | 13.04 | 10.00 |

| 2020 | 21.43 | No data | 15.38 * | 10.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Woźniak, J.; Pactwa, K.; Szczęśniewicz, M.; Ciapka, D. Declaration of the Sustainable Development Goals of Mining Companies and the Effect of Their Activities in Selected Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416422

Woźniak J, Pactwa K, Szczęśniewicz M, Ciapka D. Declaration of the Sustainable Development Goals of Mining Companies and the Effect of Their Activities in Selected Areas. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416422

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoźniak, Justyna, Katarzyna Pactwa, Mateusz Szczęśniewicz, and Dominika Ciapka. 2022. "Declaration of the Sustainable Development Goals of Mining Companies and the Effect of Their Activities in Selected Areas" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416422

APA StyleWoźniak, J., Pactwa, K., Szczęśniewicz, M., & Ciapka, D. (2022). Declaration of the Sustainable Development Goals of Mining Companies and the Effect of Their Activities in Selected Areas. Sustainability, 14(24), 16422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416422