Abstract

(1) Background: Social capital linking, bridging, and bonding have become fascinating options for sustainable development in rural Malaysia. (2) Objective: The aims of this research were (i) to evaluate how leadership styles affect the social capital in rural Malaysia, and (ii) to examine the moderating role of motivation in enhancing these relationships. (3) Methods: The researchers utilized a quantitative approach to analyze data collected through a self-administered survey involving 190 members of the Village Development and Security Committee (JKKK) in Malaysia. The concept of “leadership quality” was measured based on transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership, while “motivations” cover its extrinsic and intrinsic components. The data were analyzed using a structural equation modeling (SEM) technique. (4) Results: The findings reveal that transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership types are essential to increase social capital in rural Malaysia. It may therefore be suggested that community leadership and its effective styles should be nurtured within the rural community to address more complex problems regarding social capital development. On top of that, extrinsic and intrinsic motivations also appeared to be significant moderating factors in determining social capital development in rural Malaysia. (5) Conclusions: Based on the results, community leaders with different leadership styles may offer better social benefits to the rural community by using various incentives to engage rural residents in facilitating social activities. (6) Policy recommendations: This study suggests further implications for academics and policy makers focused on social capital for sustainable rural development in Malaysia.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, Malaysia and other developing Southeast Asian nations have experienced high economic and social development growth, which has aided the local populations in coping with sudden economic shocks such as the recent COVID-19 crisis. Policy makers in the region face a challenge in managing adverse risks such as the global pandemic while simultaneously preserving past hard-won poverty reductions. Future economic development strategies may be required to safeguard people’s well-being, especially in rural regions where inequality of opportunities is still prevalent. According to Binswanger [1], social capital (SC) is a type of assets-based development that is implicated in the neo-endogenous and bottom-up approaches that have become popular methods for promoting the development of underdeveloped rural regions in recent years.

SC is currently a crucial resource for achieving sustainable development in developing nations. Nasihuddin [2] found that SC is a prerequisite for the conditions required for sustained community development, since it links and improves access to resources outside the community. A similar study also demonstrated that SC could potentially improve rural household sustainable livelihood assets in Jiangxi Province, China [3]. Meanwhile, according to Putnam [4], SC has been proven as a potential source of regional economic growth and development. Proper attention to the impacts of SC is expected to yield more favorable results in the effort to transform the lives of rural communities. As previously defined by Ajayi and Otuya [5], rural development is a social process that enables humans to progress and be more capable of coping with and exerting some influence over changing local conditions and environment.

Current observations in the field indicate a definite need for SC to foster rural development. Given that SC (or at least the appropriate kind of SC) may be less abundant in rural areas, people living there face more difficulties in engaging in innovative and fruitful local development activities. This difficulty is purported by the lack of direly needed competent local community leadership that channels rural residents’ efforts toward meaningful development [6]. To coordinate community activities, promote SC, and improve community sustainability, rural communities must have strong leadership. Almaki [7] suggested that the rural communities’ leadership is a driving force that utilizes assistance provided by the government to develop local resources for the benefit of the rural population. Leaders are the main force behind development programs—they give their community a better sense of each program’s direction. Additionally, leaders also help in creating networks with outsiders. This element is crucial in ensuring that the communities may quickly benefit from external support that complements their lack of skills and expertise [8]. Consequently, local leaders such as chiefs and village heads should realize the importance of SC in developing the areas under their jurisdiction. Aspects of community leadership strongly influence the formation of SC in a community and contribute to the overall rural development process.

In the rural development context, the improvement of SC also depends on the residents’ motivation to participate in rural community activities. Within the field of behavioral sciences, the concept of motivation is used to explain why people choose to participate in communal activities [9,10]. Conceptually, motivation is the catalyst that prompts someone to perform or behave in a specific manner [10]. Due to its impact on individual behavior’s direction and intensity, motivation plays a crucial role in the development of SC and various decision-making processes [11]. According to previous studies [12], extrinsic motivation can change into intrinsic motivation in certain supportive circumstances. Residents must be motivated if they are to participate, according to Rasoolimanesh and Jaafar [13], who note that motivation steers individuals toward their objectives and result in favorable circumstances for them. A prior study also highlighted the moderating effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on rural practices [14].

Against this backdrop, the goal of the current study is to fill a gap in the literature on the connection between motivation, community leadership, and SC development in rural communities. Our research focuses on rural Malaysia, where residents generally seldom participate in initiatives for rural development activities organized by numerous organizations [15]. It has been established that this is a widespread phenomenon that includes urbanites and is not exclusive to the rural population. Past research has attempted to explain why this is the case but to no conclusive end. Meanwhile, it has been asserted that solid community leadership is crucial for guiding communities toward proper developmental paths. The literature also implies that the success of rural communities as a whole is tied to leadership and how people feel about their communities [16]. Although motivation is increasingly being included in researchers’ attempts to understand human behavior [17], our understanding of their sources and consequences remains lacking. To date, several qualitative studies assessed the challenges of local leaders in rural community development in the Malaysian context [18,19]. Remarkably, the literature has largely ignored the connection between community leadership, SC cultivation, and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the context of rural area development in rural Malaysia. Therefore, the study’s primary objective was to investigate the connection between SC and community leadership and then to look at how intrinsic and extrinsic motivation moderate this association.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Capital in a Rural Community

SC is a “social structure” that expresses how individuals within a society may pool their talents and work together for shared objectives in groups and organizations that strive toward progress [20]. Various studies have examined the function of SC in differing contexts on rural development, such as the pooling of social rules for managing the commons [21], the allocation of local resources for a regional development strategy based on both individual and social values [22], the promotion of bottom-up approaches based on the locality’s knowledge [23], and the production of public goods [24]. Rural communities are generally expected to have abundant SC [25]. According to academics, SC supports rural actors’ ability to limit the detrimental effects of rural abandonment, unemployment, and social marginalization [26]. Additionally, SC may support new types of regional administration and proper environmental management [27].

SC is often described as a measure of social interaction, cohesion, and networking [28]. Higher levels of SC may improve the accessibility and reliability of knowledge and information, which will positively affect community participation and cohesiveness [29]. Additionally, SC impacts economic well-being through the creation of trust—which lowers transaction costs and increases economic activity—and through maintaining good market order via reward and punishment processes [30]. In addition, SC may be broken down into two types: bridging SC (which refers to relationships between members of various groups) and bonding SC (which relates to ties inside groups) [31]. Higher levels of bridging SC may increase community cohesiveness, which is what must happen in all communities to enable various groups of people to get along well together. A combination of bridging and bonding SC offers the best environment for rural community development [32]. Everyone wants to reach their full potential, feel a sense of belonging, and participate in their community [33]. Therefore, bridging SC would be imperative in strengthening the links between diverse groups, effectively supporting the interests of the community as a whole instead of the needs and demands of any specific segments within the community [34].

On the other hand, the best way to bring about more inclusive changes and outcomes in rural communities is through encouraging the formation of linking SC in addition to bonding and binding SC. This is because linking SC promotes communication, cooperation, and trusting relationships among locals who interact across explicit, formal, or institutionalized power gradients. For instance, farmers with stronger bridging and linking SC are likely to have a greater absorptive ability to learn and assimilate information about new (cutting-edge) practices and technologies from sources outside of the farm, according to Micheels and Nolan [35].

2.2. Community Leadership and Social Capital

Community leaders serve as a driving force for rural community development, a role that has become imperative in achieving successful and sustainable rural growth. Community leadership differs from the traditional definition of leadership, which is “about ‘leaders’ asking, persuading, and influencing ‘followers’” [36]. Typically, community leadership is less hierarchical [37], often based on volunteer action [8], involves the creation of SC [38], acts as a symbol for change [39], and necessitates many grassroots innovations. Furthermore, community leaders are frequently unofficial, unelected figures [40]. Community leadership is not a well-defined term [39] but rather is defined by the boundaries of the community in which it exists.

Moreover, community leadership can consist of one individual or a group. Chan [41] found that effective community leadership enhances community relationships and SC and increases the likelihood of community actions. Strong leadership builds SC, and concurrently, efforts to develop SC breed new leaders.

2.3. Malaysian Rural Society and Its Social Capital

Rural community development is crucial for the welfare of residents in Malaysia, as the country’s rural regions generally still have poor infrastructure, low population densities, and limited access to public services [42]. Agriculture is a significant source of revenue and employment creation for rural communities in many regions of the country. The second rural development plan, created in 1962, emphasized the importance of rural people actively participating in government programs within the context of overall national development. The Village Development and Security Committee (JKKK) was established as the primary mechanism for people’s involvement in the conception, execution, and management of development initiatives targeted to them [18]. The JKKK controls the entire village’s development and serves as a conduit for communication between the different social institutions in the villages.

The capacities of the leadership within the JKKK, especially regarding village administration, mobilizing community resources, organizing programs and activities, developing networking with agencies, and maintaining the wellness of the village community, are key success factors for sustainable rural development. The Malaysian federal government also recognizes the significance of good and effective leadership at the community level as a tool for igniting villagers’ enthusiasm and participation in local community development programs. Furthermore, effective leadership is also needed to raise the villagers’ awareness of the various economic opportunities to be reaped, such as those present in small-scale industries, tourism, and agriculture, and to facilitate collaborations on social initiatives [43]. The most crucial thing here is to motivate the rural population to participate in government initiatives aimed at improving rural regions. The government recognizes the necessity to educate the village inhabitants on how to use the various facilities provided to them. Therefore, strengthening the JKKK improves the district officer’s capacity to indirectly inspire local initiatives within the broader community development endeavor [44].

The JKKK—which focuses on rural planning and development and seeks to lessen regional differences in the quality of life for rural residents—tends to emphasize income equality as the pertinent indicator of economic well-being. This has resulted in the committee ignoring several problems such as the lack of accessibility and social inclusion that often result in rural folks missing out on opportunities for economic development [45]. Therefore, it is appropriate to pay more attention and resources to foster SC development. Investment in the nourishment of SC at the community and household levels may further improve the standard of living for locals. Community leadership and motivating elements are crucial to prevent rural residents from falling behind their urban counterparts.

Consequently, the success of JKKKs’ leadership is crucial for the growth of SC among local communities [46]. However, much current research concentrated on JKKK qualities for local community leadership and empowerment [47,48,49]. There is still a need for researchers to investigate what factors drive JKKK members’ motivation to improve their SC—which may include better community leadership and other factors.

2.4. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

This study used social exchange theory (SET) to determine which factors can enhance SC in rural communities. The SET is a relationship maintenance theory that seeks to comprehend the exchange of resources between individuals and groups throughout interactions [50]. Davlembayeva [51] noted that SET has served as the groundwork for explaining how rural people’s attitudes toward the impacts of SC development are formed. In the rural context, Ali and Yousuf [52] attempted to explain rural people’s attitudes toward the effects of SC using SET as a framework. The SET proposes that rural people who perceive personal benefits from SC development are inclined to express positive attitudes towards it, effectively supporting rural community development. Consequently, SC and social networking in rural communities allow for resource sharing and provide better access to services that connect people to families, groups, organizations, and communities both within and outside the area.

Based on the above theory [53], this study stipulates that empowering leadership positively affects SC in the rural community. Furthermore, according to the SET, when the economic, environmental, and sociocultural benefits are positive, local leaders encourage SC development. It is worth noting that these impacts comprise mainly extrinsic outcomes for the SC. However, the SET also takes into account intrinsic rewards. Ritzer and Stepnisky [54] note in their analysis of Blau’s [53] study that “rewards that are exchanged can be either intrinsic (for instance, love, affection, respect) or extrinsic (e.g., money, physical labor)”. Acknowledging the SET and its related literature, this study utilizes six sets of independent and explanatory variables. The independent variables consist of transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and laissez-faire leadership. On the other hand, the explanatory variables consist of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations that explain the impact of leadership on SC.

Transformational leadership influences both individuals and social systems [55]. Previous studies have demonstrated a positive connection between transformational leadership and SC. For instance, Abu-Rumman [56] discovered a substantial correlation between the sense of SC among German medical directors and the transformational leadership style of executive management. Transformative leadership enhances person–organization fit (P-O fit), which in turn aids the emergence of organizational SC, according to a previous study that employed social identity theory [57]. Transformational leaders, according to Sommer [58], serve as admired, trusted, and respected role models who encourage idealized behavior in accordance with high ethical and moral standards. Additionally, transformational leaders foster justice perceptions of the leader and the community by demonstrating individualized consideration for team members, which nurtures horizontal relationships of trust among rural community members. This study, therefore, proposed the following hypothesis:

H1.

Transformational leadership is related to SC in rural Malaysia.

Transactional leadership is a style of leadership that is primarily appealing to followers’ self-interests to motivate and guide them. According to Hassan and Davenport [59], community leaders can work to build up SC in their interactions with their neighborhood, which they can then contribute as a resource to a partnership. They also accumulate collaborative SC in their interactions with these partnerships, which serves as a resource in retaining their community leadership role. It is difficult to maintain and accumulate SC stocks in both of these partnerships simultaneously. A transactional leader motivates community members primarily through contingent reward exchanges [60]. Although only a few studies have been conducted on the benefits of transformative leadership on SC, leaders oversee and influence a critical portion of these resources [61,62]. Therefore, a second hypothesis was proposed:

H2.

Transactional leadership is related to SC in rural Malaysia.

According to Wong and Giessner [63], laissez-faire leadership is described as a type of leadership that allows followers to set rules and make decisions [64]. To date, the mainstream notion of laissez-faire leadership has been passive. Despite the fact that most empirical findings of this particular leadership suggest a negative association with subordinates’ attitudes and performance [65], some studies suggest that laissez-faire leadership may have a positive impact on subordinates’ innovation propensity, since it may facilitate an environment in which innovation can occur [66]. Autonomy-supportive leaders foster a sense of self-determination among team members in laissez-faire leadership [67]. Barker and Cheney [68] revealed that a community with high autonomy produces self-control situations. Self-managed teams need to control and regulate themselves by making their own rules. This condition strengthens team culture and adds to team cohesiveness by forming highly close, homogeneous, and intimate human ties. Team members may form a relatively dense network. Consequently, team autonomy and the density of a network inside teams can both be beneficial. According to a prior study by Sommer [58], autonomous workers may be more likely to have extensive social networks in addition to a variety of links, thus creating a hybrid of bridging and bonding ties that support autonomous instrumental activity. On the other hand, Sommer [58] highlighted the role of SC and laissez-faire leadership in a rural fishing community. Building on this legacy of past research, the current study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3.

Laissez-faire leadership related to SC in rural Malaysia.

To improve SC development, it is crucial to comprehend the nested interactions between internal and external motivators that lead to involvement in local community activities. These motivations include targets existing within the individual or group that incite human behavior and actions to be involved in community activities [12]. The encouragement of local people to participate in certain community-based activities can also come from intrinsic motivations beyond economic incentives. In explaining these aspects of motivation, previous studies have identified its two mutually exclusive dimensions: intrinsic and extrinsic motivations [12].

An individual’s innate drive to express self-identification is referred to as intrinsic motivation [14]. Zhang [69] claimed that SC already present in the community and intrinsic motivation are both connected. Encouragement from others boosts one’s intrinsic drive and motivates them to devote more time and effort to assisting others, since SC acts as the glue that holds people who are working on a particular project together. The importance and effects of transactional, transformational, and laissez-faire leadership styles on the intrinsic motivation of banking industry employees were also discovered [70]. According to SET, when leaders adopt a variety of leadership styles, they encourage and focus on every individual member, which in turn motivates them to see their importance and creative potential. Members thus encounter a higher level of intrinsic motivation [71], which results in a higher level of SC. Intrinsic motivation was also found to be a moderator in rural practices [14]. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H4.

Intrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between the predictors and SC in rural communities.

H4-1.

Intrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and SC in rural communities.

H4-2.

Intrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between transactional leadership and SC in rural communities.

H4-3.

Intrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between laissez-faire leadership and SC in rural communities.

Extrinsic motivation is defined as a driving behavior in response to environmental incentives or disincentives [72]. Due to its impact on SC, extrinsic motivation is a significant external driving element during the decision-making process. Extrinsic incentive affects an individual’s decision to engage in an activity in a rural community [73]. Members “must be motivated if they are to participate”, according to Rasoolimanesh and Jaafar [13]. Extrinsic motivation, such as social rewards, persuades members toward goals and favorable conditions, thus encouraging them to participate in decision-making processes. Miles and Morrison [74] demonstrated that external motivation also has a significant relationship with three leadership styles (i.e., transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire). No studies have examined the role of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation as a moderator of the association between community leadership and SC in the rural community, despite a growing number of studies highlighting the moderating role of motivation in predicting knowledge sharing and work engagement. Acknowledging this apparent gap in the body of knowledge, the following hypotheses were put forth:

H5.

Extrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between the predictors and SC in rural communities.

H5-1.

Extrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and SC in rural communities.

H5-2.

Extrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between transactional leader-ship and SC in rural communities.

H5-3.

Extrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between laissez-faire leadership and SC in rural communities.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measurements

Harter’s [75] assessment was utilized to measure extrinsic motivation (three items) and intrinsic motivation (four items). In addition, this study used six items to measure bonding SC, 11 items to measure bonding SC, and 12 items to assess linking SC from the World Bank’s “Integrated Questionnaire for Social Capital Measurement” (SQ-IQ) [76]. Moreover, the German 36-item Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire was adopted to measure three leadership styles: transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire [77]. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The measuring items were developed specifically for the context of this study. Two professional researchers investigated the items’ content validity. Two independent translators who are native speakers of Malay translated the questionnaire using the forward translation approach [78]. A university lecturer with over 25 years of expertise in teaching English who has written books in both Malay and English was one of the translators. The other translator was a former JKKK member, who had spent 18 years teaching students in both Malay and English in schools. The study team merged the two translators’ translated surveys into a single translated questionnaire. When two distinct words were selected during the compilation process, both translators were consulted via a group chat, and a discussion took place until an agreement was achieved on which word to retain. Members of the JKKK were also the subjects of the pilot research. The steps taken above resulted in some modifications to the wording and structure of the questionnaire.

3.2. Data Collection

A total of 190 respondents were chosen for the study to achieve its objectives. A multistage random sampling method was used to select the respondents. The study covers a population of 69,810 JKKK members. A G-Power analysis was used to establish the right sample size for the necessary analyses. The respondents were chosen from a group of JKKK members in 24 select communities in Peninsular Malaysia that cover the following states: Terengganu (representing the east coast zone), Perak (representing the middle zone), Kedah (representing the northern zone), and Johor (representing the southern zone).

Data were gathered between November and December 2021. Using a stratified random sampling approach, 250 questionnaires were distributed throughout the above four Malaysian states. Based on the experience of past studies on rural areas [79], a field team technique was adopted using surveys recruited from within the research setting by ten local individuals who are familiar with the local community and its culture, while not requiring highly experienced interviewers. After eliminating incomplete questionnaires, a final sample of 190 people was selected from that group, registering a valid response rate of 79.89%. The demographics of the respondents were outlined using descriptive statistics.

The research model created for this study was validated by the researchers using PLS-SEM algorithms [80]. The authors ran the PLS algorithms using a bootstrapping method set to 5000 subsamples using Smart-PLS 3.0, the data analysis program [81]. Due to its capacity to accommodate the intricate study model and the limited sample size (n = 190), the PLS method was chosen over other regression models as the analytic method for this investigation [82]. The fundamental PLS method proposed by Lohmöller [83] was implemented in SmartPLS software. It comprises three stages: (1) iterative estimate of latent constructs scores is a four-step iterative technique that was performed until convergence (or the maximum number of iterations) was obtained; (2) estimation of outer weights/loading and path coefficients; (3) estimation of location parameters.

Using the moderation interaction technique, the moderating influence of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation in the community leadership–SC link was investigated. The mean impact of confidence intervals with non-zero values was significant at 0.05. The normed fit index was employed to indicate the incremental measure of model fit, and the standardized root mean square residual was utilized to evaluate the differences between the actual and anticipated correlations.

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

Gender, ethnicity, marital status, age, educational level, work sector, and monthly income were all part of the demographic profile of the sample population. The majority of the respondents were male (72.9%), Malay (92.9%), and married (90.0%). The respondents’ ages ranged from 24 to 70 years of age. Education-wise, the highest qualification obtained by most respondents was Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM) (the Malaysian Certificate of Education is a nationwide test taken by all Malaysian fifth-form secondary school students; it is the equivalent of the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) in England) (47.1%), and 14.7% graduated from institutes of higher education. Respondents are from various work-related backgrounds ranging from self-employed (47.6%), government servants (22.9%), government and private retirees (12.4%), to private employees (10.0%). Most respondents are from the lower income bracket, earning below 2500 MYR (528 USD) (58.2%).

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for the study’s variables are displayed in Table 1. The results of this investigation demonstrated that all constructs have positive correlations with one another, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.540 to 0.680.

Table 1.

Constructs’ descriptive analysis.

4.3. Measurement Model

Results from the PLS-SEM algorithm indicate that the CFA model accurately matches the data (SRMR = 0.059; NFI = 0.946) [81]. To assess the measuring model, various tools including construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminate validity were used [84]. As a rule of thumb, the composite reliability (CR) for each construct should be more than 0.70 [85]. The CR of each construct ranged from 0.940 to 0.966 when factor loadings less than 0.7 were excluded from further analysis, demonstrating their reliability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measurement model assessment.

The measurement’s convergent validity was examined by analyzing the average variance extracted (AVE) [86]. The results demonstrate that all constructions are valid as the AVE for each is larger than 0.5 (Table 2). The heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) and the Fornell and Larcker [87] criteria were employed to assess discriminant validity. The Fornell and Larcker criteria findings suggest that all HTMT values are significantly below 0.85. Furthermore, the results of the HTMT reveal that the square root of the AVE for each construct is larger than the correlation between constructs. The results illustrate that discriminant validity for the model is confirmed (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 4.

HTMT criterion.

4.4. Structural Model

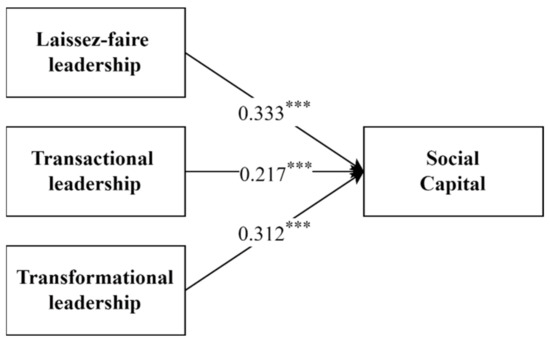

The structural model used in this study was tested using the path coefficient (β), t-values, and coefficient of determination (R2) [81]. In addition, the predictive relevance (Q2) and effect sizes (f2) are also reported. The exogenous variables—transformational leadership (β = 0.352, p = 0.00), transactional leadership (β = 0.227, p = 0.00), and laissez-faire leadership (β = 0.313, p = 0.001)—jointly explain 60% of the variation in SC, as per the reported R2 (0.60). Hence, H1–H3 are validated (Table 5 and Figure 1). In this study, all Q2 values are more than zero, with Q2 = 0.429 of SC [81]. These results suggest that the model is capable of making accurate predictions.

Table 5.

Hypotheses testing.

Figure 1.

Diagram for the structural model of the study. *** p < 0.001.

4.5. Moderation Effect of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivations

Table 6 outlines the results of the moderation analysis, based on H4 and H5, that extrinsic and intrinsic motivations moderate the relationship between laissez-faire leadership and SC (β = 0.066, t = 2.268; β = 0.043, t = 3.704), and H4-3, as well as H5-3, are supported. Extrinsic motivation positively moderates the relationship between transactional leadership and SC (β = 0.043, t = 3.704), effectively supporting H5-2. The findings further demonstrate that the link between transformative leadership and SC is significantly and positively moderated by intrinsic motivation (β = 0.053, t = 1.816). From here, it may be concluded that H4-1 is supported.

Table 6.

Structural model assessment (moderation effects).

4.6. Reverse Causality Test

The influence of SC on leadership is judged to be greater than that of leadership on SC in the composition of the fundamental causal relationship. This study investigated the risks of reverse causality, specifically whether SC had any negative effects on the leader-ship variable. We applied the two-stage Heckman test. In the first stage, we investigated the leadership and SC regression coefficients and R2. In the second stage, we conducted the two-stage Heckman test. Leadership was first grouped by the median, and those who exceeded the median were assigned 1; otherwise, 0. A Probit model was also applied to compute the regression coefficients of SC on leadership. SC has a significant and positive effect on leadership (p < 0.05), indicating the possibility of reverse causality. Therefore, using STATA 17.0, the inverse Mills ratio was calculated and incorporated into the regression model alongside SC. In comparison to the first stage, the regression coefficients of SC in the Stata results did not change significantly. Therefore, despite the risk of reverse causality in the research model, the results obtained through the use of the SmartPLS remained robust.

5. Discussion

This is the first known study that investigates the moderation roles of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation in the association of community leadership and SC in rural Malaysia. This study extends existing knowledge by providing a framework to assess leadership styles—transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire—and community SC. From this perspective, the findings draw some significant conclusions and offer advice to local leaders to assist them to continue to develop appropriate leadership behaviors. Although intrinsic motivation is gaining more attention as an approach to explain human behavior, research on how different motives for acting affect SC development in rural communities remains lacking.

More specifically, the primary study objectives were achieved through a survey of members of the JKKK in rural Malaysia. The findings of this study demonstrate that transformational and transactional leadership styles were associated with SC (H1 and H2 were accepted). The results were consistent with the previous studies [74,88,89], which found that SC increased by enhancing the leaders’ transactional and transformational leadership styles. This study points to potential liability for rural individuals associated with leaders who are transformational and transactional. The transformational leadership process is a vital catalyst for creating and maintaining a community infrastructure that increases the quality of life, lowers crime rates, and maintains a bond among the community among rural communities. In essence, such a leadership style helps make a community a good place to live in. Increased transformational leadership processes could then engage others within the JKKK community and the larger community in an ongoing effort to increase SC. Increased transformational leadership processes could then engage others within the community and the larger community in an ongoing effort to increase SC.

Moreover, transactional “top-down” skills are vital to building SC for rural development. Effective transactional leadership can be the platform from which transformational leadership (which facilitates improved community capacity) can be developed. The transactional leadership style might be better for motivating rural individuals by giving them appropriate rewards and clear directions for building SC in the rural community. The findings of this study can facilitate policy-making bodies to develop a comprehensive view of transformational and transactional leadership styles and SC in the rural context. As a result, local governments have looked to local leaders and their leadership and programs to bring the community together, building a sense of social connectedness in the rural community.

Furthermore, this study’s results show a positive and significant association between laissez-faire leadership style and SC. Therefore, H3 is supported. These results align with previous studies such as the one conducted by Springer [90] in the context of Poland’s rural areas. According to Chaudhry and Javed [91], a possible explanation of this finding is that laissez-faire leadership may create learning opportunities for followers and rural community members. In addition, Gandolfi and Stone [92] state that leadership style becomes more effective when the community is highly motivated. Thus, the study established that the laissez-faire leadership style motivates rural people in directing their energy toward dealing with problems in the community using their own decisions. Although the laissez-faire leadership style is occasionally regarded as an ineffective style, it can be effective when employees are professional, highly skilled, experienced, motivated, and capable of working independently. This type of leadership style may facilitate visionary members, with freedom to work free from interference. Therefore, the JKKK community are at the same time motivated with a high sense of responsibility. Rural individuals’ leadership should be evaluated and JKKK leaders should become aware of what is needed to attain positive results from rural individuals in order to build SC in the rural community.

Additionally, the interaction moderation analysis findings revealed that intrinsic motivation moderates the link between transformational and laissez-faire leadership styles and SC. The results further demonstrate that extrinsic motivation moderates the link between laissez-faire leadership and SC (H4-1, H4-3, H5-2, and H5-3). The results confirmed that the laissez-faire and transformational leadership styles can be adopted in situations where the JKKK community has a high level of passion and intrinsic motivation for their work to resolve collective problems more easily in the rural community. These results support the findings of previous studies [14], indicating that highly motivated community leaders expedite and facilitate the development of SC in the rural community.

Policy makers need to provide leadership training programs for JKKK leaders. In particular, drawing on our findings, laissez-faire and transformational leadership positively relate to intrinsic motivation. However, managers still lack systematic leadership training. They manage their followers according to their personal experiences. Human resource departments should provide these leadership training programs for JKKK leaders. Finally, leaders should provide an autonomous support climate to their followers, thus increasing their followers’ intrinsic motivation to build SC with their JKKK leaders in the rural community.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between leadership styles and SC among JKKK members in rural Malaysia. The results contribute towards the creation of SC in rural areas by providing additional empirical support for the capacity of all three leadership styles—transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire—in building SC in rural communities. The results also indicate that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation moderates the relationship between SC and transformational and laissez-faire leadership styles. The conclusions drawn from this work will be useful for local leaders who wish to increase the effectiveness of the actions they take in their local communities. Public institutions should help and motivate local leaders extrinsically and intrinsically to produce and adopt SC efficiently as an instrument for development. This would strengthen competitiveness, since society is the only actor capable of generating SC, especially rural areas in developing nations, where the social dimension of overall economic development cannot be ignored.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

We acknowledge the limitations of the study in that data were collected fully depending on a quantitative approach. An additional study could capture many qualitative aspects of leadership, extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, and SC in rural Malaysia. In addition, our research has proven that a longitudinal study is a useful way to monitor the relationship between leadership styles and SC formation in rural communities in the long run. We suggest that more longitudinal studies can be undertaken in the future to describe the dynamic development of this association in rural communities. Although leadership styles are deemed useful in SC, the stock of bonding, bridging, and linking SC in rural areas are not considered separately. We have demonstrated how secondary data may be utilized to map different SC typologies and give a general sense of SC across areas, which may benefit stakeholders. Due to inadequate recruiting, a strong desire to maintain anonymity, or both, far fewer women participated in the study than men. This represents a methodological limitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.M.R. and Z.Z.; methodology, Z.Z.; software, F.A.; validation, A.A.M.R., I.A.I., and Z.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; investigation, A.A.M.R.; resources, A.A.M.R. and H.A.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.M.R.; writing—review and editing, A.A.M.R. and Z.Z.; visualization, F.A. and H.A.; supervision, A.A.M.R.; project administration, I.A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UPM, with the grant number: GP-IPM/2020/969500.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akter, A.; Ahmad, N. Empowering Rural Women’s Involvement in Income Generating Activities Through BRAC Microfinance Institution in Sylhet District, Bangladesh. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasihuddin, A.A.; Pamuji, K.; Rosyadi, S.; Ahmad, A.A. The Role of Social Capital in Promoting Sustainable Rural Development Area in Banyumas Regency. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 448, 012067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Zhu, S.; Xiao, H.; Kang, X.; Xie, F. Does Social Capital Benefit the Improvement of Rural Households’ Sustainable Livelihood Ability? Based on the Survey Data of Jiangxi Province, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. Social Capital: Measurement and Consequences. Can. J. Policy Res. 2001, 2, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, R.; Otuya, N. Women’s Participation in Self-Help Community Development Projects in Ndokwa Agricultural Zone of Delta State, Nigeria. Community Dev. J. 2006, 41, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samah, A.A.; Aref, F. People’s Participation in Community Development: A Case Study in a Planned Village Settlement in Malaysia. World Rural Obs. 2009, 1, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Almaki, S.H.; Silong, A.D.; Idris, K.; Wahat, N.W.A. Understanding of the Meaning of Leadership from the Perspective of Muslim Women Academic Leaders. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2016, 6, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, M. The Role of Community Leadership in the Development of Grassroots Innovations. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 22, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayat, K. Exploring Factors Influencing Individual Participation in Community-Based Tourism: The Case of Kampung Relau Homestay Program, Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 7, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meimand, S.E.; Khalifah, Z.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Mardani, A.; Najafipour, A.A.; Ahmad, U.N.U. Residents’ Attitude toward Tourism Development: A Sociocultural Perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Md Noor, S.; Mohamad, D.; Jalali, A.; Hashim, J.B. Motivational Factors Impacting Rural Community Participation in Community-Based Tourism Enterprise in Lenggong Valley, Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective: Definitions, Theory, Practices, and Future Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M. Sustainable Tourism Development and Residents’ Perceptions in World Heritage Site Destinations. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-T.; Chang, C.-C.; Peng, L.-P.; Liang, C. The Moderating Effect of Intrinsic Motivation on Rural Practice: A Case Study from Taiwan. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2018, 55, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uster, A.; Vashdi, D.; Beeri, I. Enhancing Local Service Effectiveness through Purpose-Oriented Networks: The Role of Network Leadership and Structure. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2022, 52, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, D.; Manard, C. Instructional Leadership Challenges and Practices of Novice Principals in Rural Schools. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2018, 34, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Tiraieyari, N.; Krauss, S.E. Predicting Youth Participation in Urban Agriculture in Malaysia: Insights from the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Functional Approach to Volunteer Motivation. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, A.M.; Aziz, F.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ibrahim, A. Assessing the Challenges of Local Leaders in Rural Community Development: A Qualitative Study in Malaysia. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abukhalifeh, A.N.; Wondirad, A. Contributions of Community-Based Tourism to the Socio-Economic Well-Being of Local Communities: The Case of Pulau Redang Island, Malaysia. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringani, J.; Fitjar, R.D.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Social Capital and Economic Growth in the Regions of Europe. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2021, 53, 1412–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöck, C.; Nunn, P.D. Adaptation to Climate Change in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Literature Review of Academic Research. J. Environ. Dev. 2019, 28, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Knickel, K.; María Díaz-Puente, J.; Afonso, A. The Role of Social Capital in Agricultural and Rural Development: Lessons Learnt from Case Studies in Seven Countries. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.-T.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Chang, K.-C.; Hu, S.-M. How Social Capital Affects Support Intention: The Mediating Role of Place Identity. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebvises, P. Social Capital, Citizen Participation in Public Administration, and Public Sector Performance in Thailand. World Dev. 2018, 109, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Fink, M. Rural Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Social Capital within and across Institutional Levels. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man-Soo, J.; Joonkyung, H.; Donghun, J. Determinants of Social Capital in Korea. Seoul J. Econ. 2022, 35, 188–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani, E.; Micheletti, S. Social Capital and Rural Development Research in Chile. A Qualitative Review and Quantitative Analysis Based on Academic Articles. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, F.; Andrieu, E. Bowling Together by Bowling Alone: Social Capital and Covid-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrari, S.; Krauss, S.E.; Ariffin, Z.; Meng, L.K. A Network-Based Approach for Emerging Rural Social Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Fielke, S.; Bayne, K.; Klerkx, L.; Nettle, R. Navigating Shades of Social Capital and Trust to Leverage Opportunities for Rural Innovation. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.; Domina, T.; Petts, A.; Renzulli, L.; Boylan, R. “We’re in This Together”: Bridging and Bonding Social Capital in Elementary School PTOs. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 57, 2210–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malherbe, W.; Sauer, W.; Aswani, S. Social Capital Reduces Vulnerability in Rural Coastal Communities of Solomon Islands. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 191, 105186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Duffy, M. The Role of Festivals in Strengthening Social Capital in Rural Communities. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouet, H.; Freier, C.; Senghaas, M. Which Capital Do You Mobilise? How Bureaucratic Encounters Shape Jobseekers’ Social and Cultural Capital in France and Germany. Crit. Soc. Policy 2022, 42, 695–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheels, E.T.; Nolan, J.F. Examining the Effects of Absorptive Capacity and Social Capital on the Adoption of Agricultural Innovations: A Canadian Prairie Case Study. Agric. Syst. 2016, 145, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Beck, J.; Wu, C.; Carroll, J.M. Beyond Leaders and Followers: Understanding Participation Dynamics in Event-Based Social Networks. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1892–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyx, J.; Leonard, R.J. Complex Systems Leadership in Emergent Community Projects. Community Dev. J. 2011, 46, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, G.D.; Beaulieu, L.J. Community Leadership. In American Rural Communities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, H. Interpreting ‘Community Leadership’in English Local Government. Policy Politics 2007, 35, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénit-Gbaffou, C.; Katsaura, O. Community Leadership and the Construction of Political Legitimacy: Unpacking B Ourdieu’s ‘Political Capital’in Post-Apartheid Johannesburg. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1807–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.W.; Roy, R.; Lai, C.H.; Tan, M.L. Social Capital as a Vital Resource in Flood Disaster Recovery in Malaysia. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2018, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Economic Surveys: Malaysia. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=OECD+Economic+Surveys%3A+Malaysia+2019&oq=OECD+Economic+Surveys%3A+Malaysia+2019&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i60&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Washida, H. The Origins and (Failed) Adaptation of a Dominant Party: The UMNO in Malaysia. Asian J. Comp. Politics 2019, 4, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simin, M.H.A.; Abdullah, R.; Ibrahim, A. Influence of Local Leadership in Poverty Eradication among the Orang Asli Communities in the State of Terengganu, Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 342. [Google Scholar]

- Daskalopoulou, I. Civic Participation and Soft Social Capital: Evidence from Greece. Eur. Political Sci. 2018, 17, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binti Ahmad, A.; Bin Silong, A.D.; Abbasiyannejad, M. Competencies of Effective Village Leadership in Malaysia. Stud 2015, 4, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Charoenwiriyakul, C. Local Community Leadership and Empowerment for Rural Community Strengths. In Proceedings of the 32nd IASTEM International Conference, Moscow, Russia, 8 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Setokoe, T.J.; Ramukumba, T.; Ferreira, I.W. Community Participation in the Development of Rural Areas: A Leaders’ Perspective of Tourism. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Zhang, J.; Tian, F. Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Tale of Two Ancient Chinese Villages. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, S.; Qun, W.; Hui, L.; Shafi, A. Influence of Social Exchange Relationships on Affective Commitment and Innovative Behavior: Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davlembayeva, D.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E. Sharing Economy: Studying the Social and Psychological Factors and the Outcomes of Social Exchange. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 158, 120143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Yousuf, S. Social Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention: Empirical Evidence from Rural Community of Pakistan. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzer, G.; Stepnisky, J. Classical Sociological Theory; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi, A.; Vosta, L.N.; Ebrahimi, A.; Jalilvand, M.R. The Contributions of Social Entrepreneurship and Transformational Leadership to Performance: Insights from Rural Tourism in Iran. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rumman, A. Transformational Leadership and Human Capital within the Disruptive Business Environment of Academia. World J. Educ. Technol. Curr. Issues 2021, 13, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, U.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Syed, F.; Naseer, S. Interplay between PO Fit, Transformational Leadership and Organizational Social Capital. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, E. Social Capital as a Resource for Migrant Entrepreneurship; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, R.; Davenport, M. Application of Exploratory Factor Analysis to Address the challenge of Measuring Social Capital in a Rural Communal Setting in South Africa. Agrekon 2020, 59, 218–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, S.K.; Arkorful, H.; Martins, A. Democratic Leadership and Organizational Performance: The Moderating Effect of Contingent Reward. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 44, 1042–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A.R.M.; Genovese, A.; Brint, A.; Kumar, N. Improving Reverse Supply Chain Performance: The Role of Supply Chain Leadership and Governance Mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Khan, R.N.; Masih, S.; Ali, W. Influence of Transactional Leadership and Trust in Leader on Employee Well-Being and Mediating Role of Organizational Climate. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Aff. 2021, 6, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.I.; Giessner, S.R. The Thin Line between Empowering and Laissez-Faire Leadership: An Expectancy-Match Perspective. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 757–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, L.; Sunderman, H.; Hastings, M.; McElravy, L.J.; Lusk, M. Leadership Transfer in Rural Communities: A Mixed Methods Investigation. Community Dev. 2021, 52, 382–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, T.; Gulseren, D.B.; Kelloway, E.K. The Benefits of Transformational Leadership and Transformational Leadership Training on Health and Safety Outcomes. In Increasing Occupational Health and Safety in Workplaces; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, Z.; Khan, I. Leadership Theories and Styles: A Literature Review. Leadership 2016, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, I. Positive Effects of Laissez-Faire Leadership: Conceptual Exploration. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 1246–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.R.; Cheney, G. The Concept and the Practices of Discipline in Contemporary Organizational Life. Commun. Monogr. 1994, 61, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, X. Social Capital, Motivations, and Knowledge Sharing Intention in Health Q&A Communities. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1536–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareen, M.; Razzaq, K.; Mujtaba, B.G. Impact of Transactional, Transformational and Laissez-Faire Leadership Styles on Motivation: A Quantitative Study of Banking Employees in Pakistan. Public Organ. Rev. 2015, 15, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, M.; Lei, Z.; Song, X.; Sarker, M.N.I. The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Employee Creativity: Moderating Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2020, 25, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, X.; Velez, M.A.; Moros, L.; Rodriguez, L. Beyond Proximate and Distal Causes of Land-Use Change: Linking Individual Motivations to Deforestation in Rural Contexts. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y. What Makes Better Village Development in Traditional Agricultural Areas of China? Evidence from Long-Term Observation of Typical Villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.P.; Morrison, M. An Effectual Leadership Perspective for Developing Rural Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. A Model of Mastery Motivation in Children: Individual Differences and Developmental Change. In Aspects of the Development of Competence: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology; Collins, W.A., Ed.; Psychology Press: Minneapolis, MI, USA, 1981; Volume 14, pp. 215–256. [Google Scholar]

- Grootaert, C.; Narayan, D.; Jones, V.N.; Woolcock, M. Integrated Questionnaire for the Measurement of Social Capital; The World Bank Social Capital Thematic Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Felfe, J. Validierung Einer Deutschen Version Des “Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire “(MLQ Form 5 × Short) Von. Z. Arb.-Organ. AO 2006, 50, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, Adaptation and Validation of Instruments or Scales for Use in Cross-Cultural Health Care Research: A Clear and User-Friendly Guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwambale, F.M.; Moyer, C.A.; Komakech, I.; Fred-Wabwire-Mangen; Lori, J.R. The Ten Beads Method: A Novel Way to Collect Quantitative Data in Rural Uganda. J. Public Health Res. 2013, 2, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.-K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, G.C.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Roldán, J.L. Prediction-Oriented Modeling in Business Research by Means of PLS Path Modeling: Introduction to a JBR Special Section. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4545–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, J.-B. Predictive vs. Structural Modeling: Pls vs. Ml. In Latent Variable Path Modeling with Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; pp. 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Quo Vadis? Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Nazem, F.; Gheytasi, S. Validation Scale for Measuring the Leadership Style (Transformational and Transactional Leadership Style) In Education Ministry. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2014, 8, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Suhendra, R. Role of Transactional Leadership in Influencing Motivation, Employee Engagement, and Intention to Stay. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Entrepreneurship, Surabaya, Indonesia, 22 October 2020; KnE Social Sciences: Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia, 2021; pp. 194–210. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, A.; Bernaciak, A.; Walkowiak, K. Diagnoza Stylu Przewodzenia Wielkopolskich Burmistrzów–z Wykorzystaniem Kwestionariusza MLQ [Diagnosis of the Leadership Style of the Mayors of Greater Poland-with the Use of the MLQ Questionnaire](Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire). Eduk. Ekon. Menedżerów 2018, 47, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, A.Q.; Javed, H. Impact of Transactional and Laissez Faire Leadership Style on Motivation. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, F.; Stone, S. Leadership, Leadership Styles, and Servant Leadership. J. Manag. Res. 2018, 18, 261–269. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).