Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Rural Tourism in the Sustainable Socio-Economic Revitalization of Rural Areas

2.1. Theoretical and Conceptual Background

2.2. An Overview of the Evolution of Rural Tourism in Romania

2.3. Rural Tourism and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development in Romania

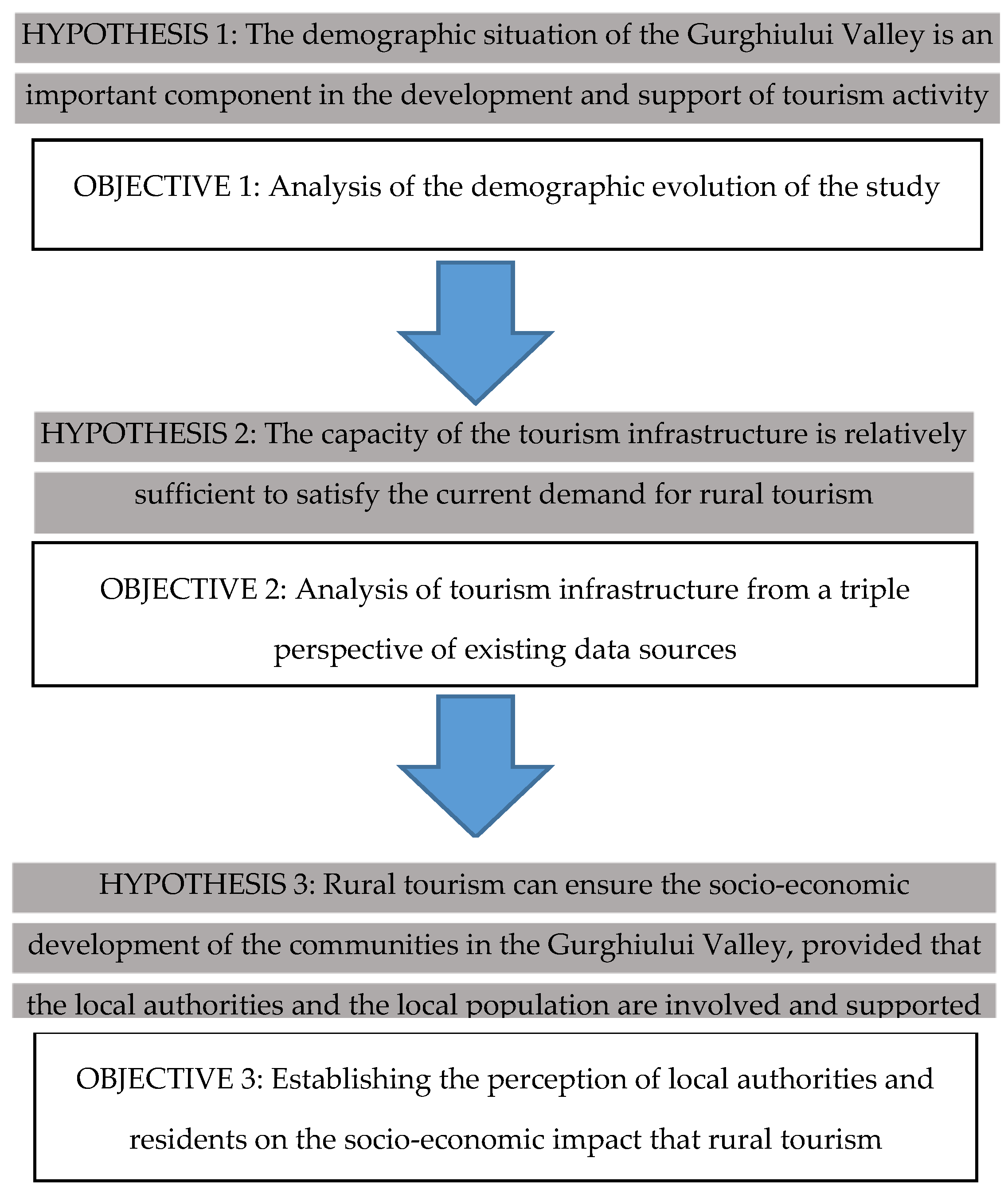

3. Materials and Methods

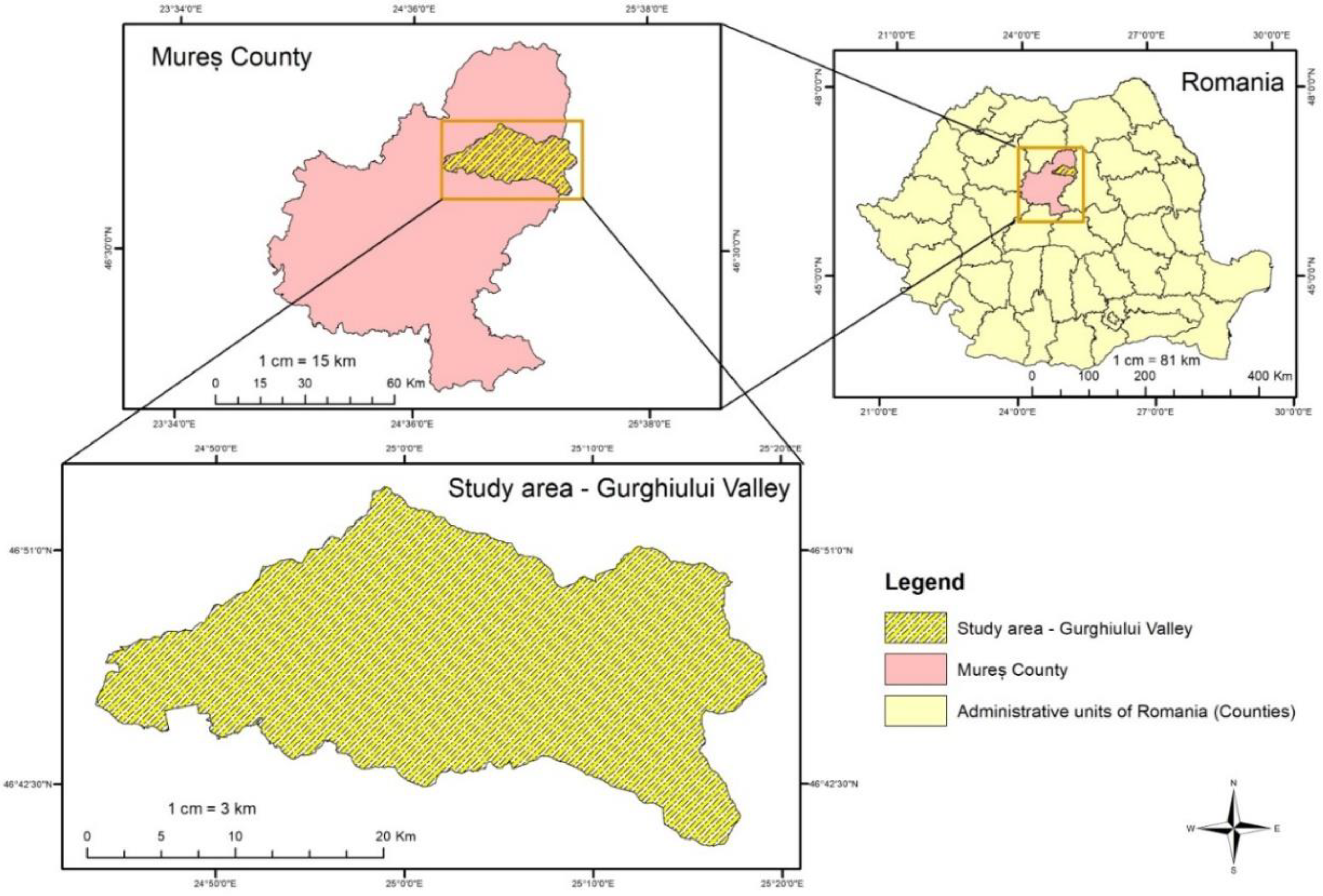

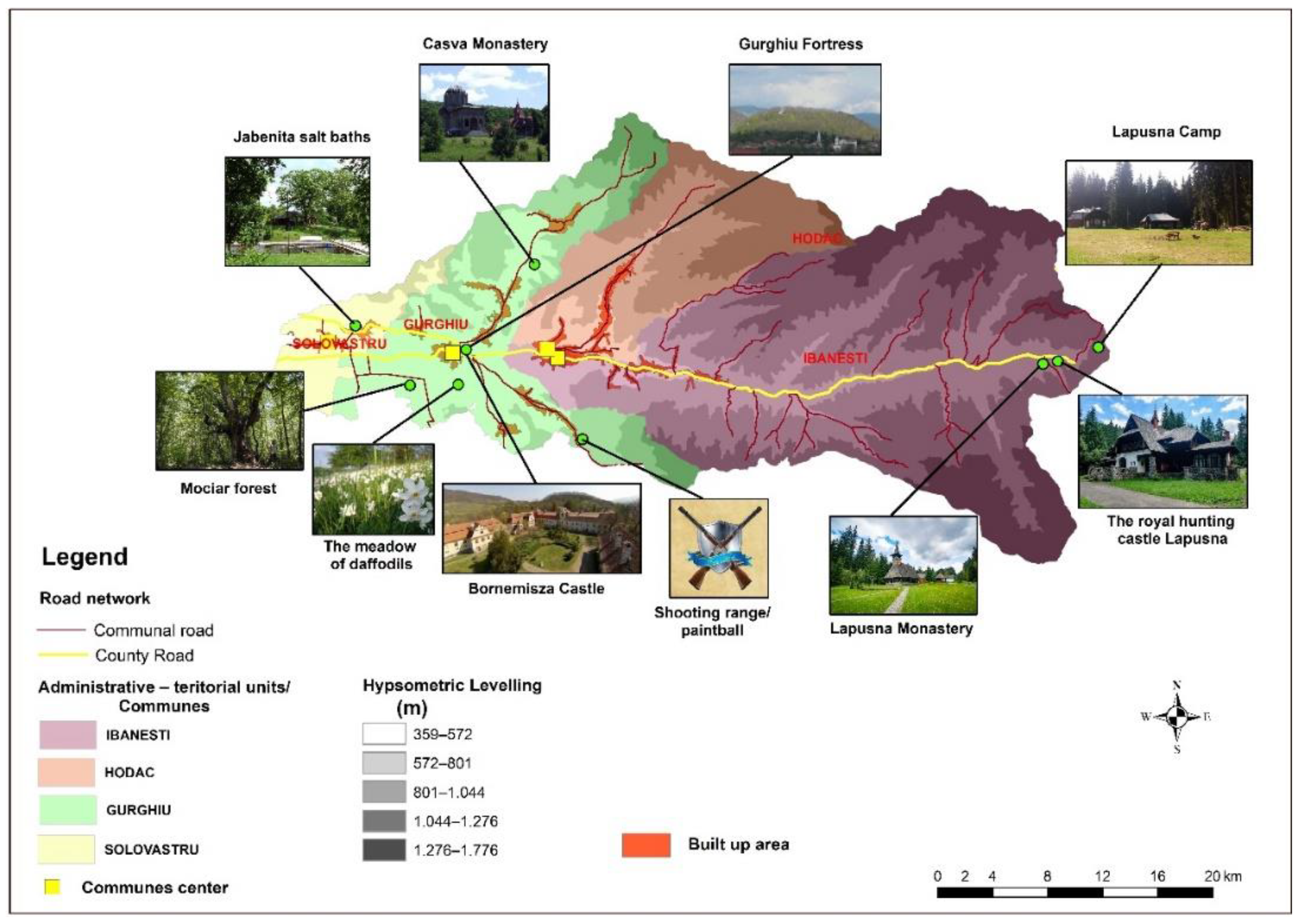

3.1. Study Area: The Main Geographical Features—Favorable Premises for Outlining Attractive Tourist Offerings and the Development of Rural Tourism

3.2. Research Methodology

4. Results and discussion

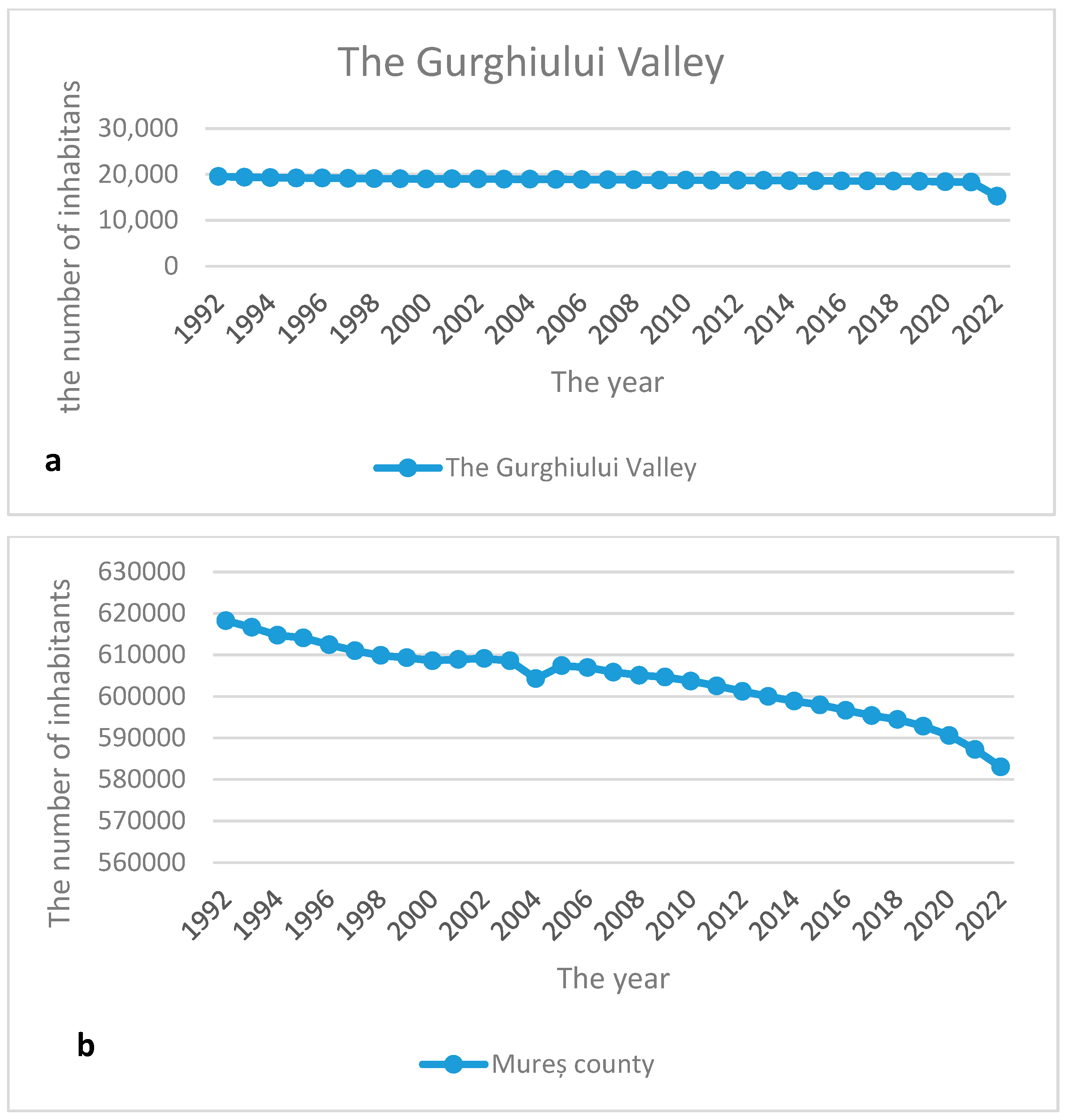

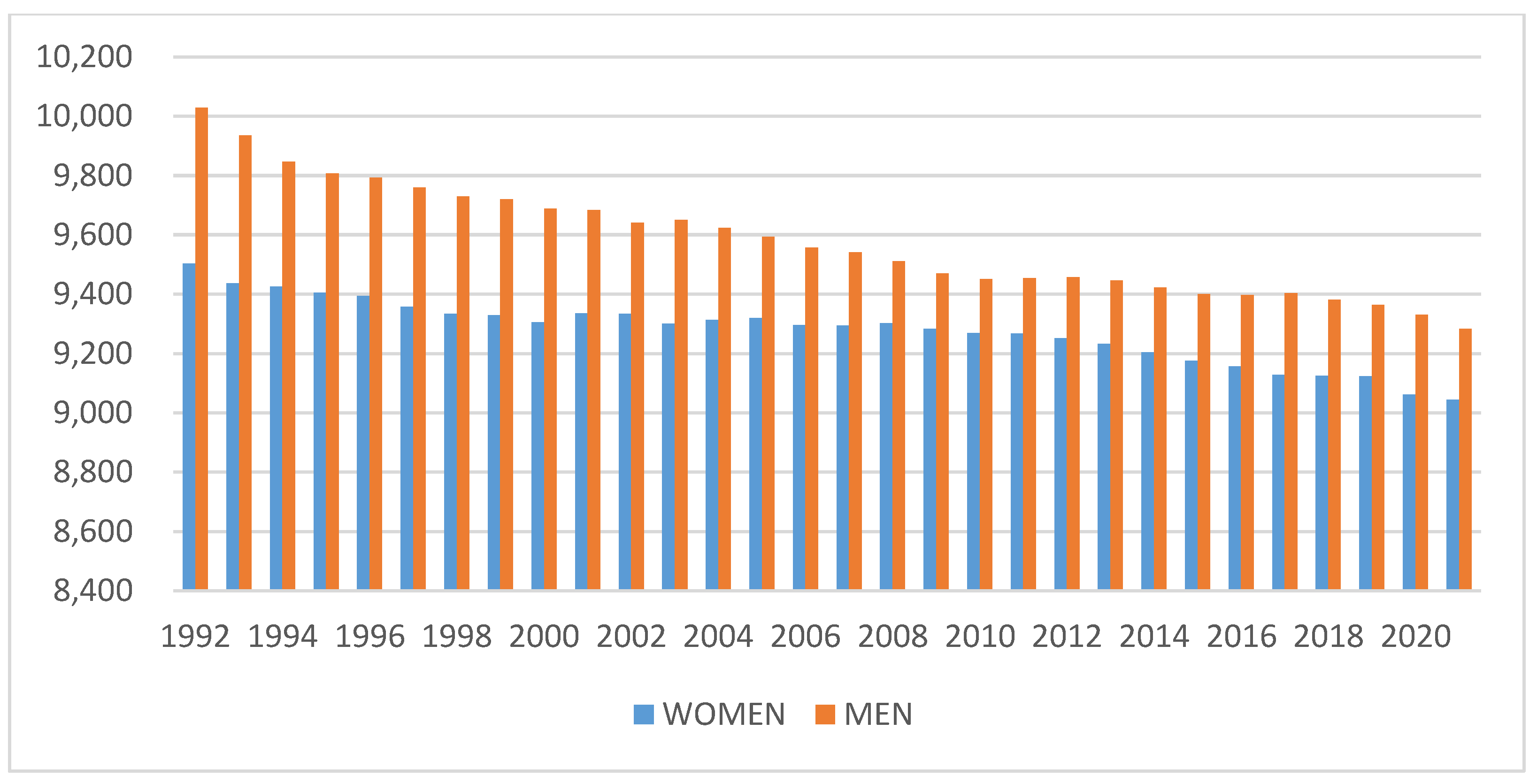

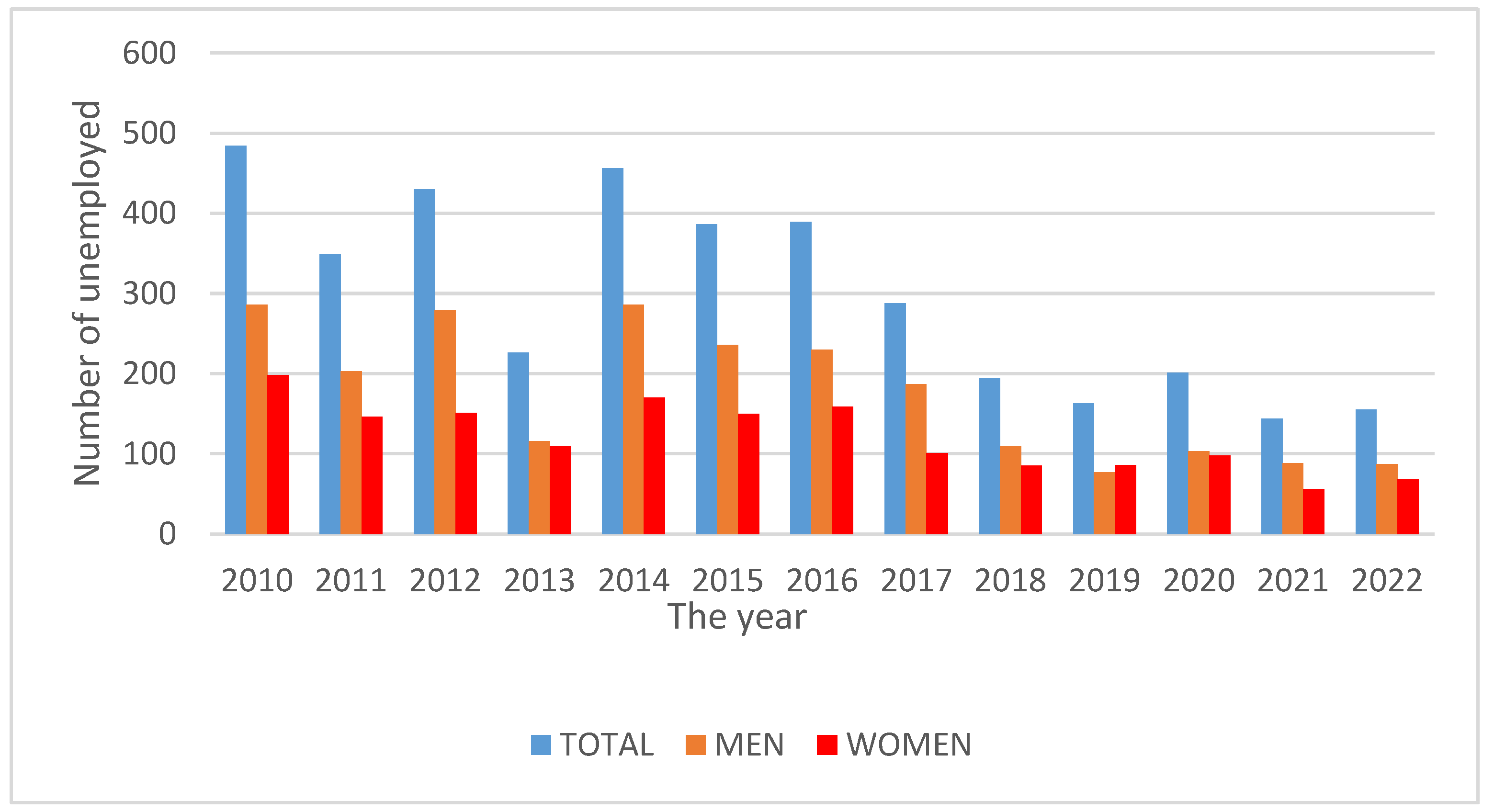

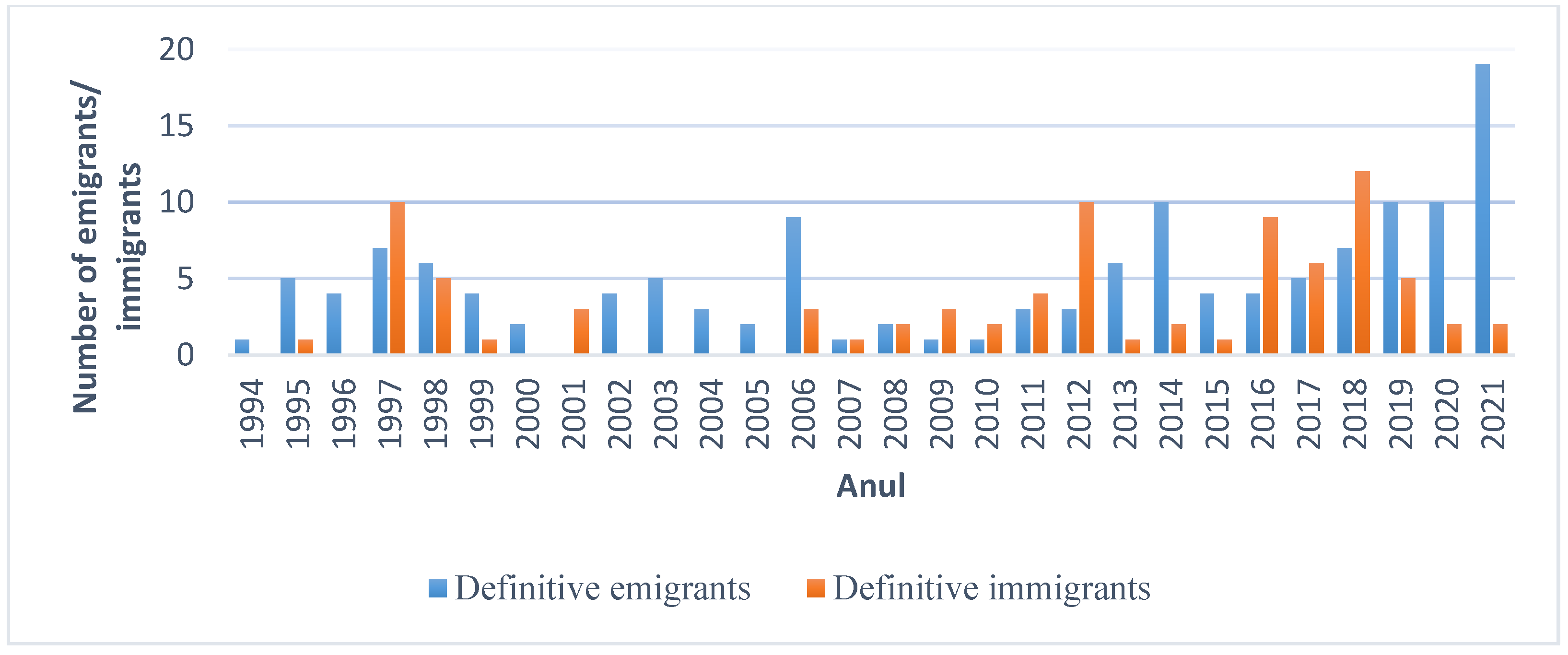

4.1. Aspects Related to the Economic and Social Development of the “Valley of the Kings”—The Gurghiului Valley

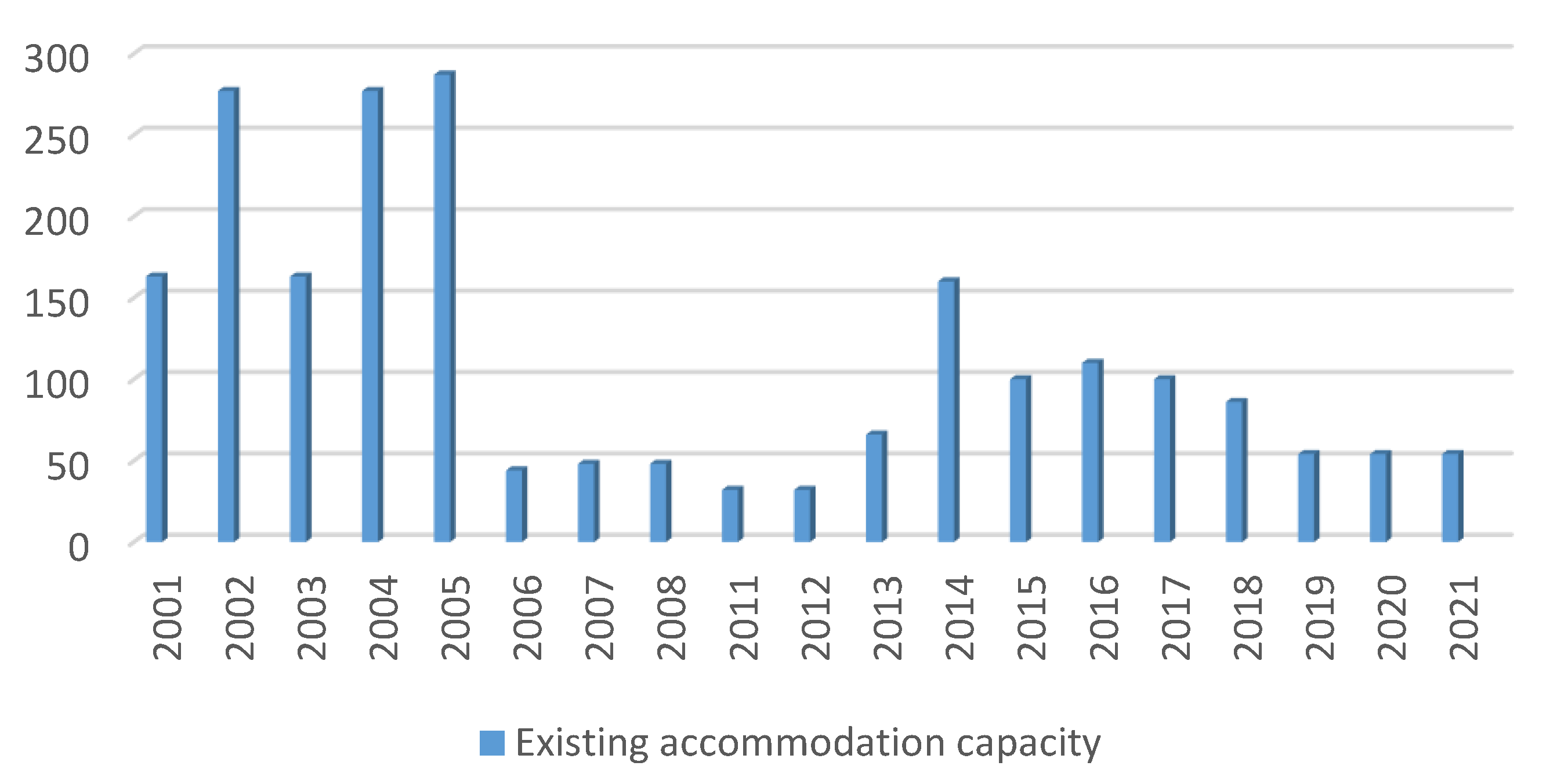

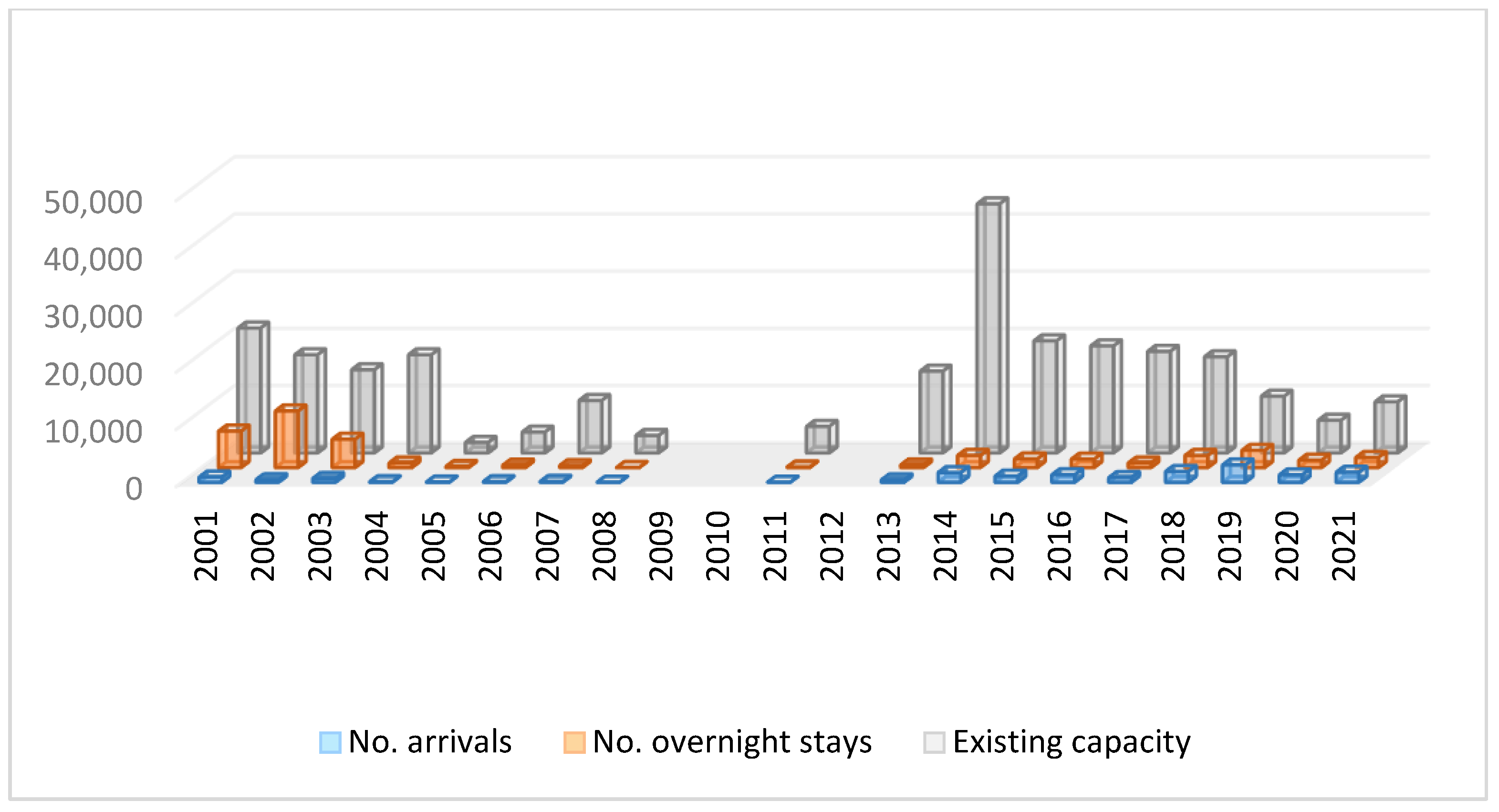

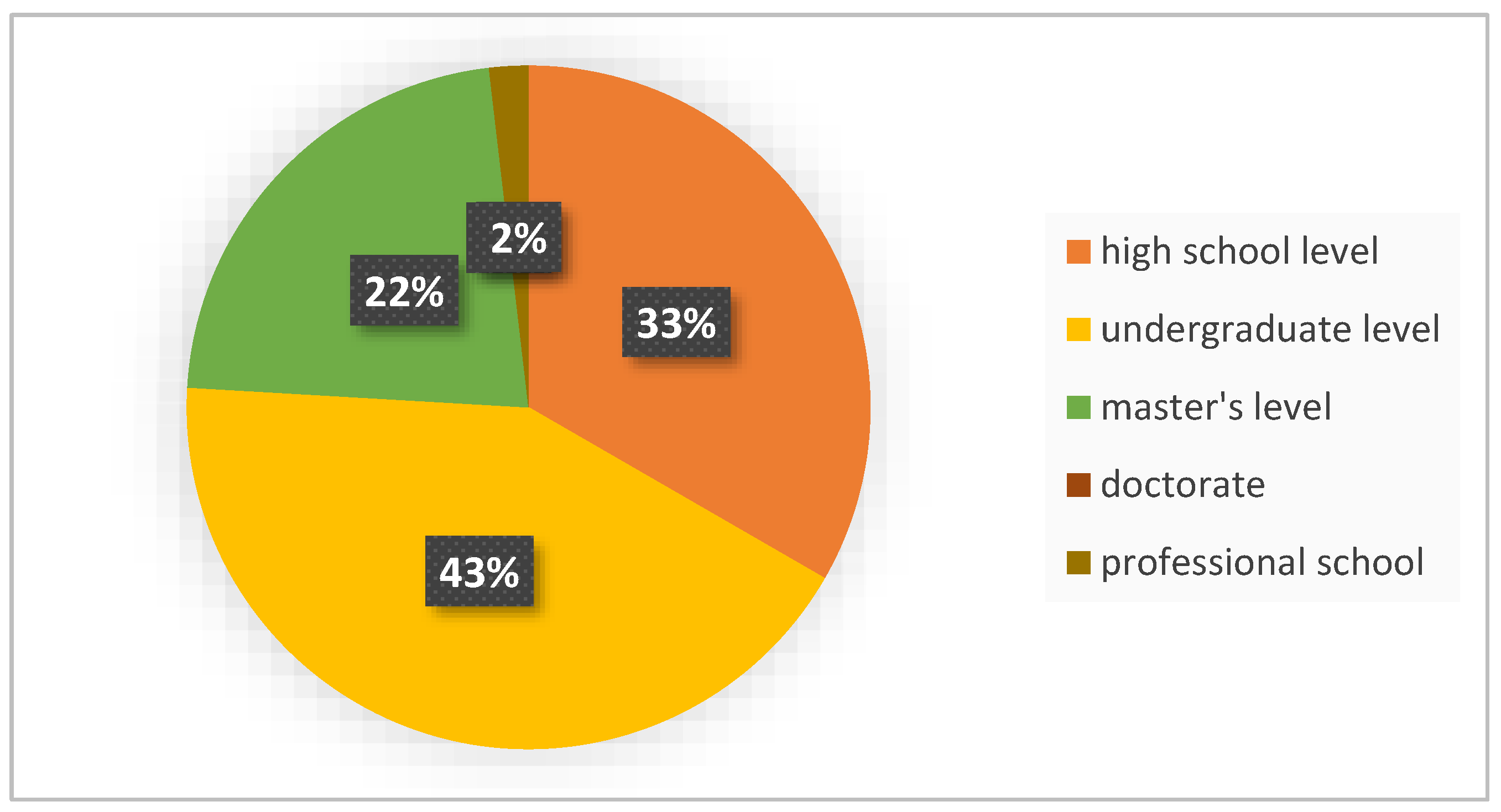

4.2. Aspects Related to Tourist Activity in the “Valley of the Kings”—The Gurghiului Valley

- The existence or non-existence of a strategy for the development of rural tourism within each analyzed commune;

- The degree of openness of local authorities to tourism activity;

- The degree of knowledge of the local leaders regarding the existing tourism potential in the perimeter of their ATUs;

- The method of promotion existing until now regarding the promotion of the commune on a tourist level;

- The types and forms of tourism considered to be triggering or supporting elements of rural tourism.

- The existence of tourism development strategies at the town hall level (three of the four ATUs currently have such a strategy, each with a different direction: the restoration and conservation of anthropogenic tourist objectives—Ibănești commune; the diversification of tourist offerings and/or the design of an original, unique tourist product— Hodac commune; the development of tourist infrastructure such as accommodation, catering, transport and leisure—Gurghiu commune).

- Local leaders consider rural tourism to be an economic component that could contribute, to an extent of approximately 70%, to the economic development of the local community, especially in the entire area subject to research (the Gurghiului Valley).

- The low degree of openness of local authorities regarding the establishment of a tourism service within their municipalities.

- The lack of a clear vision from the local leaders on the categories of tourist resources, especially on those that could trigger and support the practice of rural tourism.

- The modest knowledge of local authorities about the types and forms of tourism that can be practiced and, implicitly, that can support the development of the tourism phenomenon.

- The local respondents place rural tourism among the economic activities that can substantially contribute to the economic and social development of the local community.

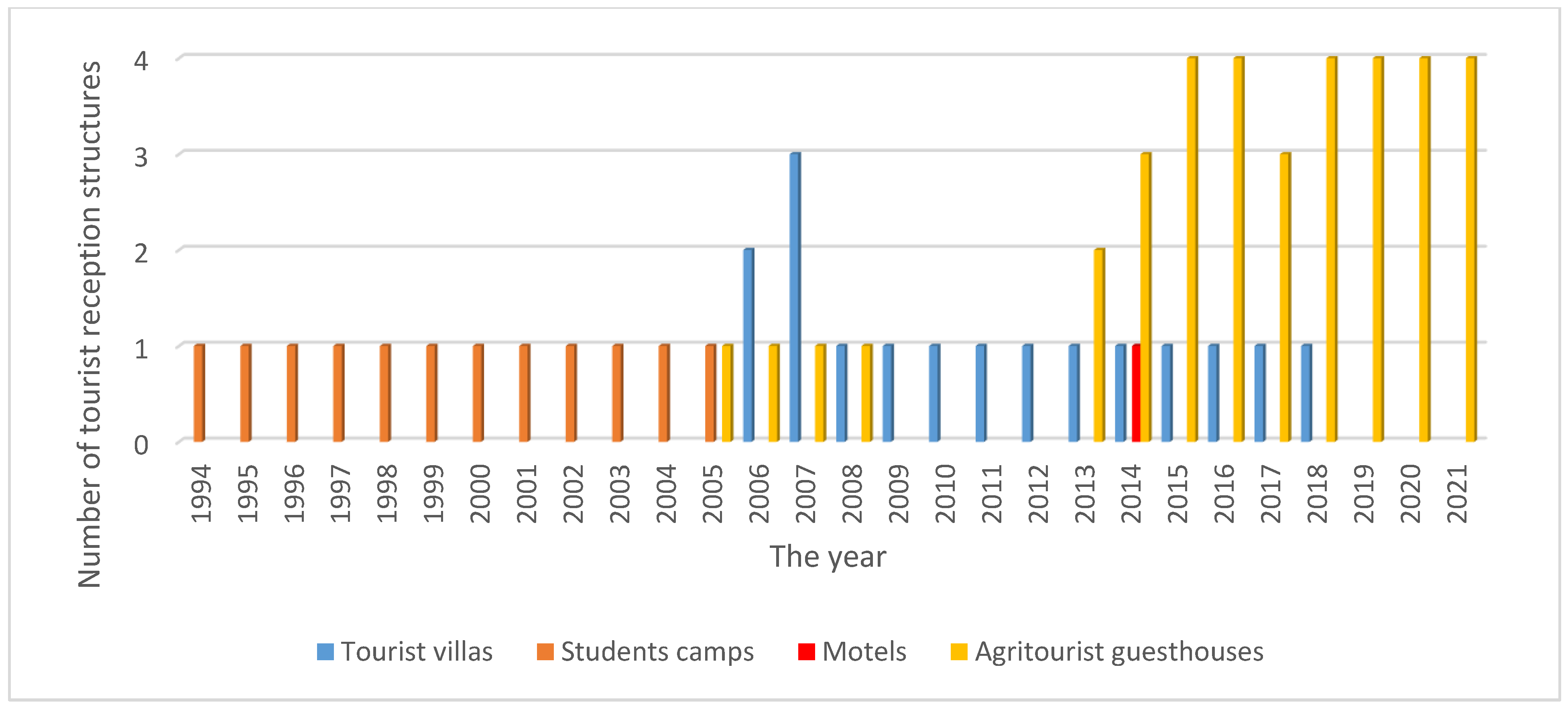

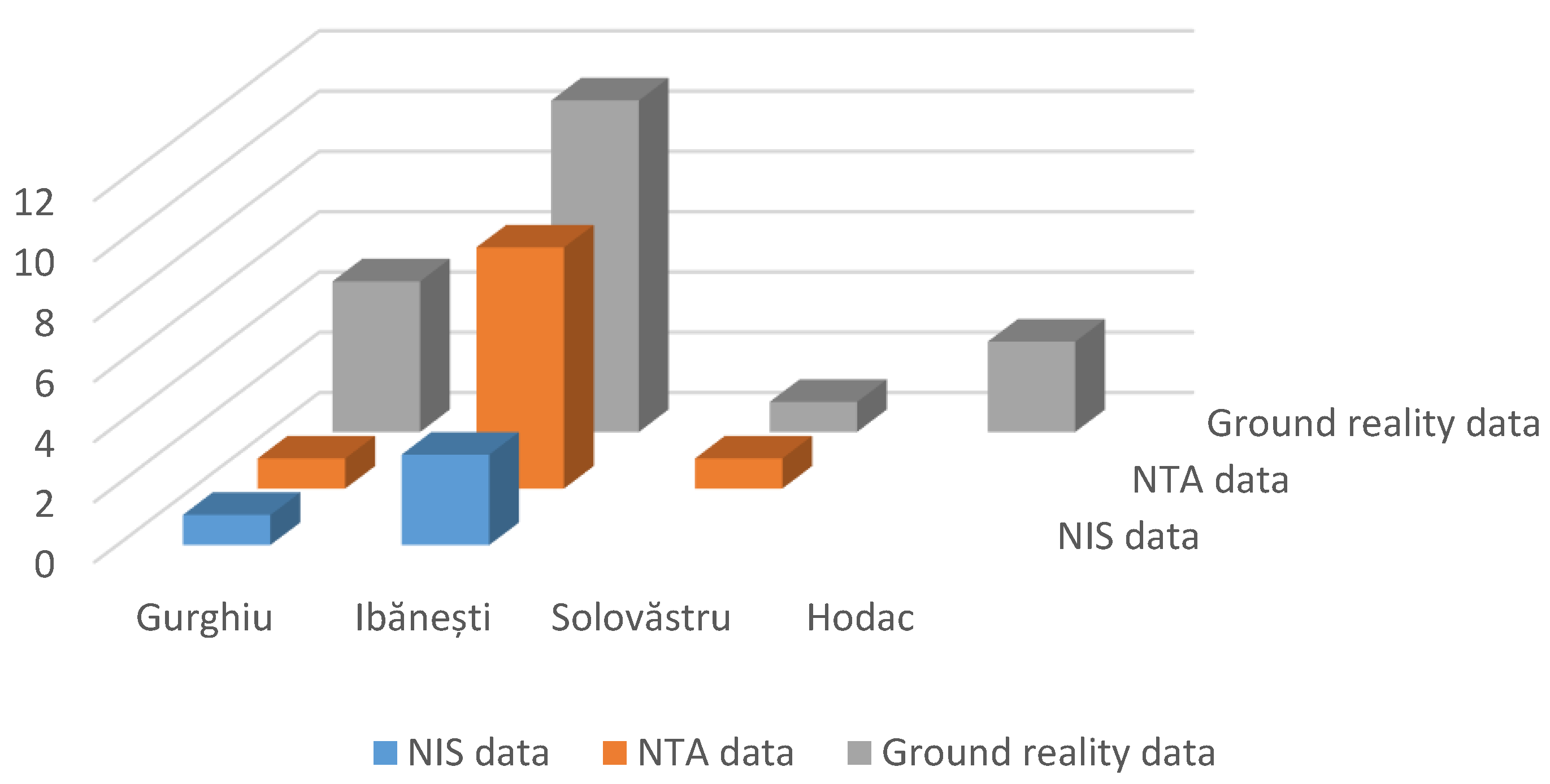

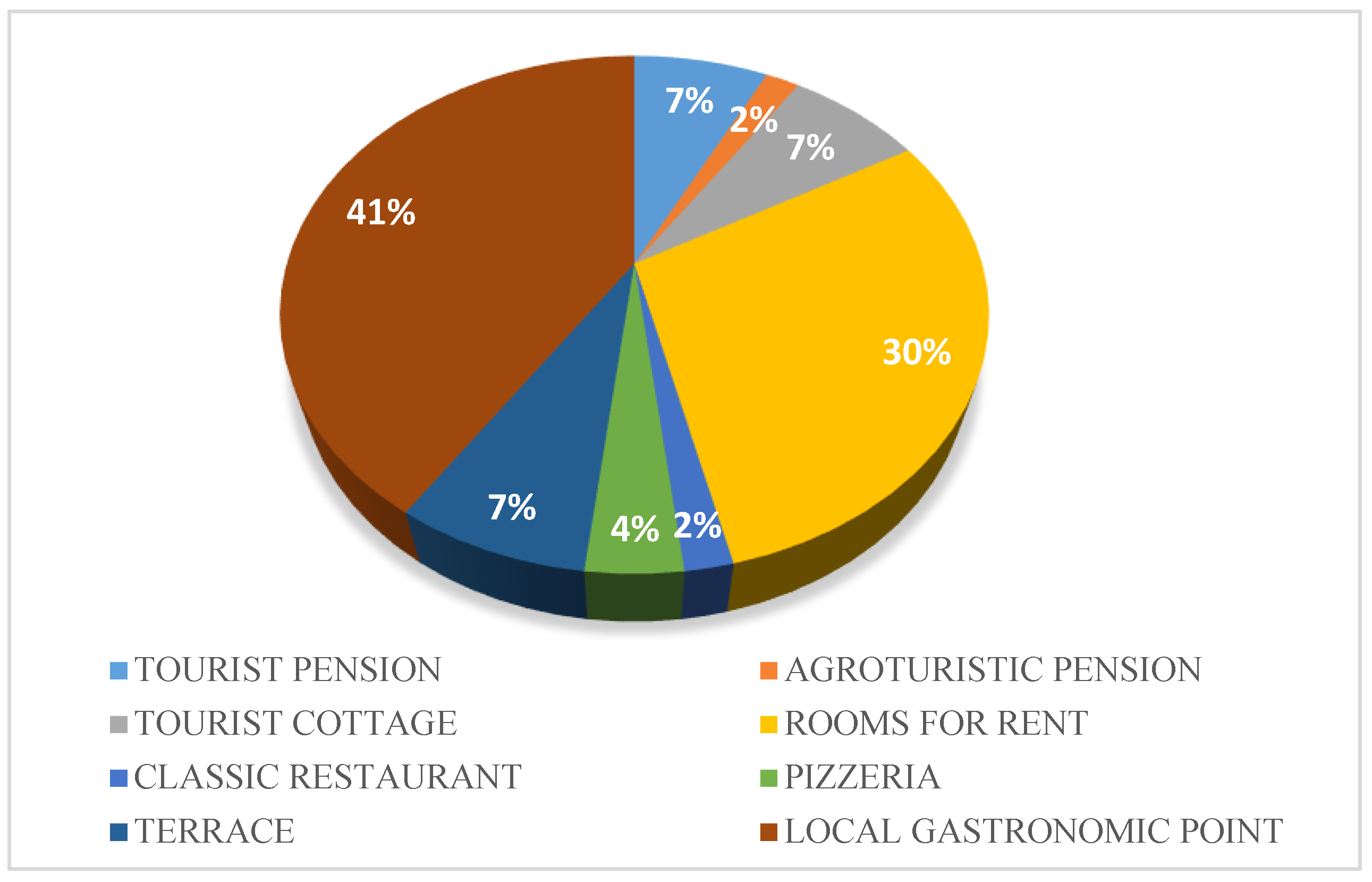

- There exist some tourist reception structures with the functions of accommodation and public catering in the administrations of the surveyed locals; the most numerous are from the category of local gastronomic locations and rooms for rent, but, as can be seen on the graph below, they also occur in other categories of tourist reception structures (with accommodation or catering functions) (Figure 15).

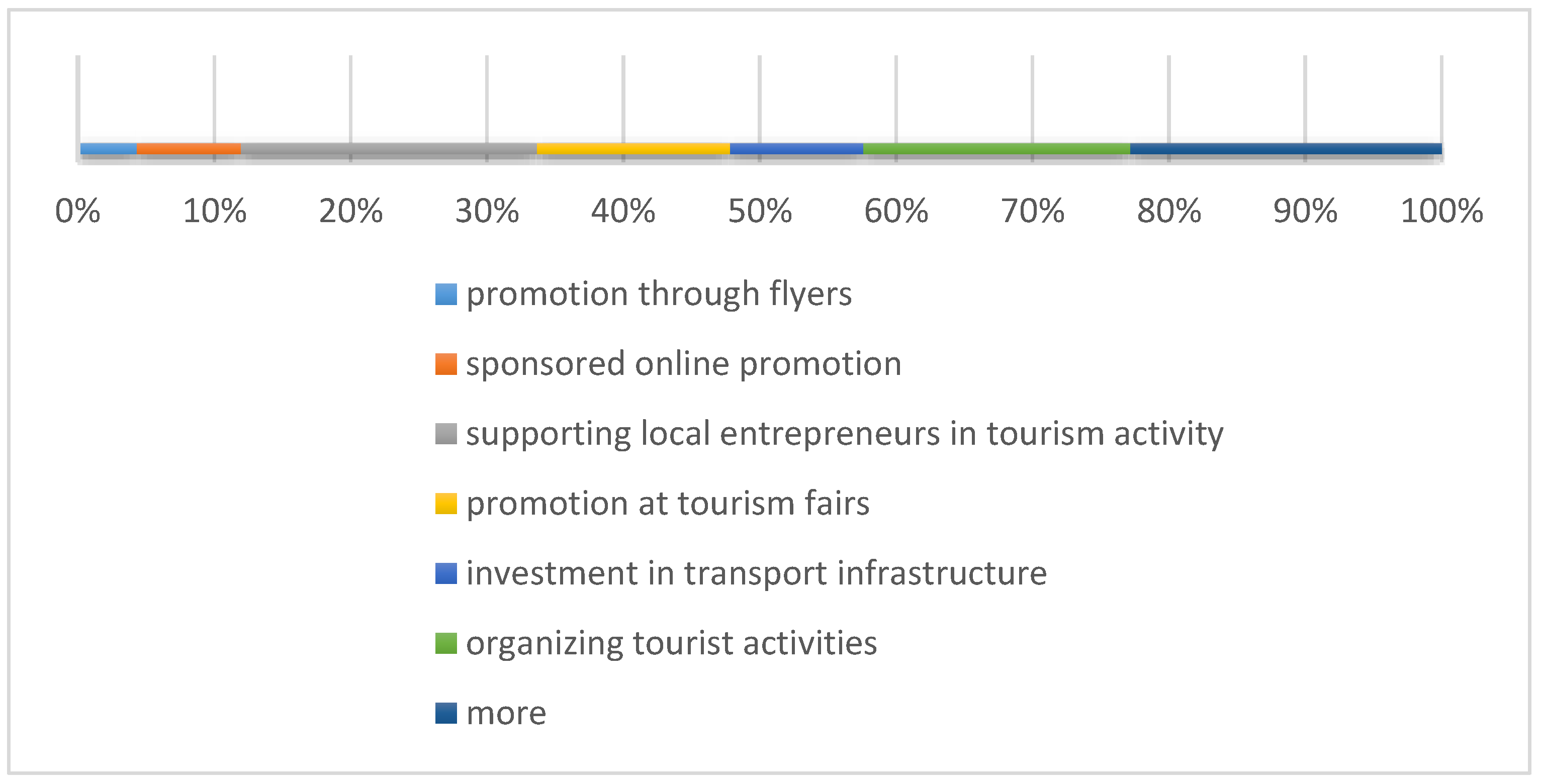

- There is a positive image of the locals in terms of the degree of involvement and the methods of tourism promotion used by the local authorities; the most common method of promoting tourism, formulated by locals and supported by local authorities, include support for local entrepreneurs and the organization of tourism activities; however, as can be seen in Figure 16, local authorities have (to a lower extent, in the opinion of respondents) also used other methods of promotion, which shows their desire to promote the area from a tourism point of view.

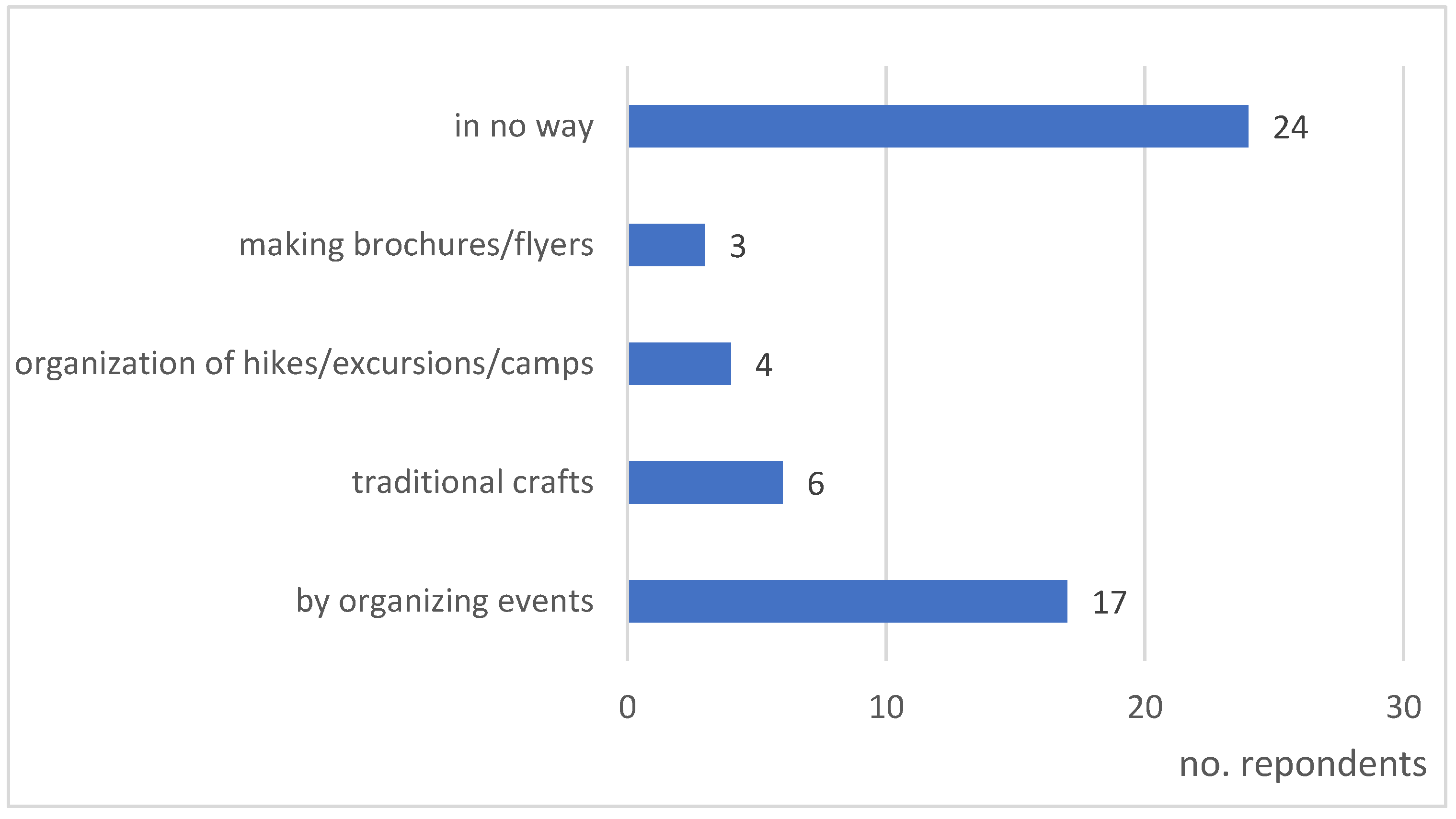

- There is insufficient involvement of local residents regarding the promotion and support of rural tourism in the area; most of the respondents have no involvement in this regard, which shows a lack of attention from the residents regarding the importance of tourism in the development of the community (Figure 17).

- There is a lack of knowledge in respondents regarding the existing tourism resources and the tourism potential of the area, given that no respondent mentioned ethnographic resources and events (important tourism resources in the research area).

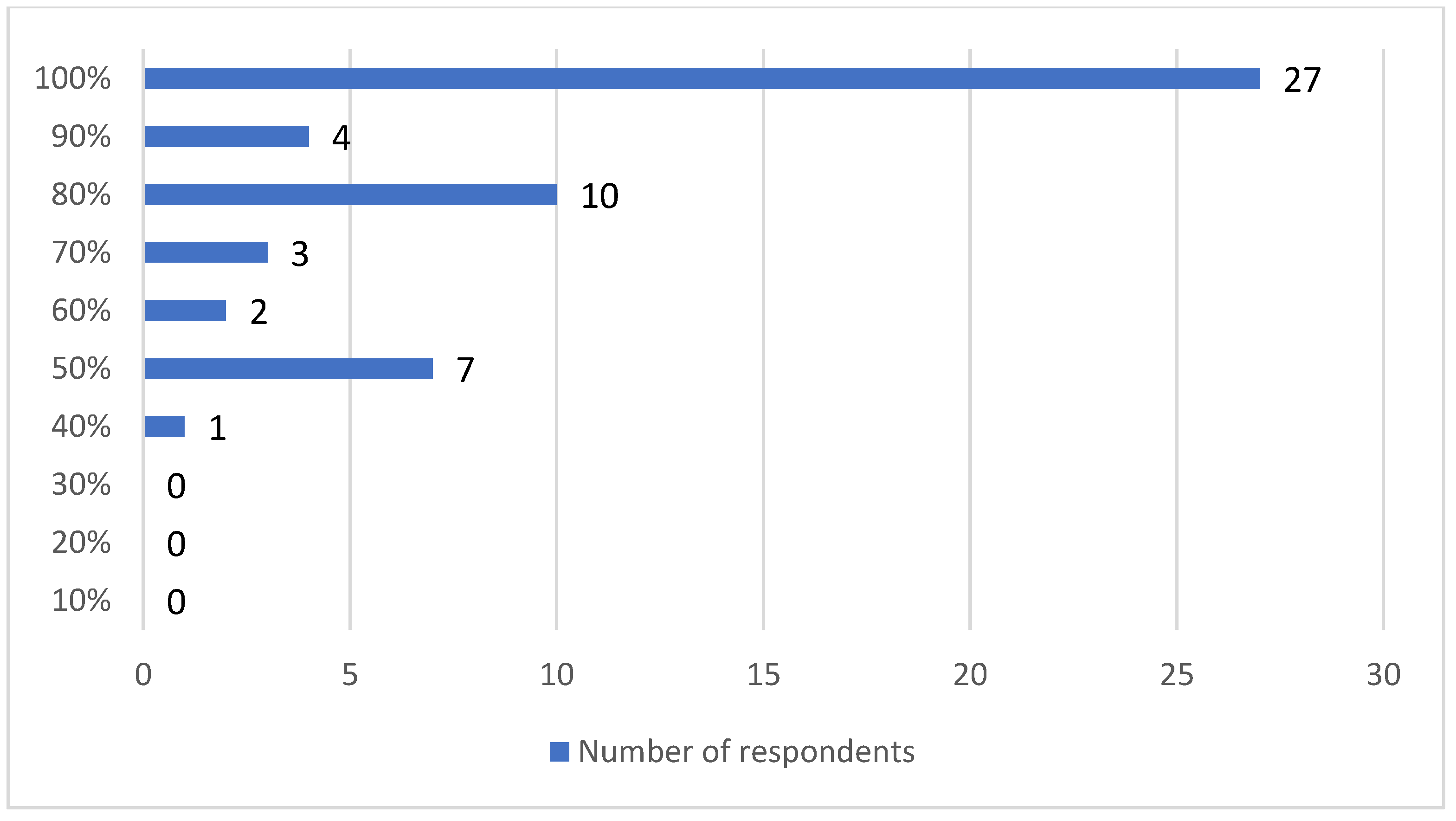

- Most respondents (over 80%) are convinced that rural tourism would help the development of the local community they belong to (Figure 18).

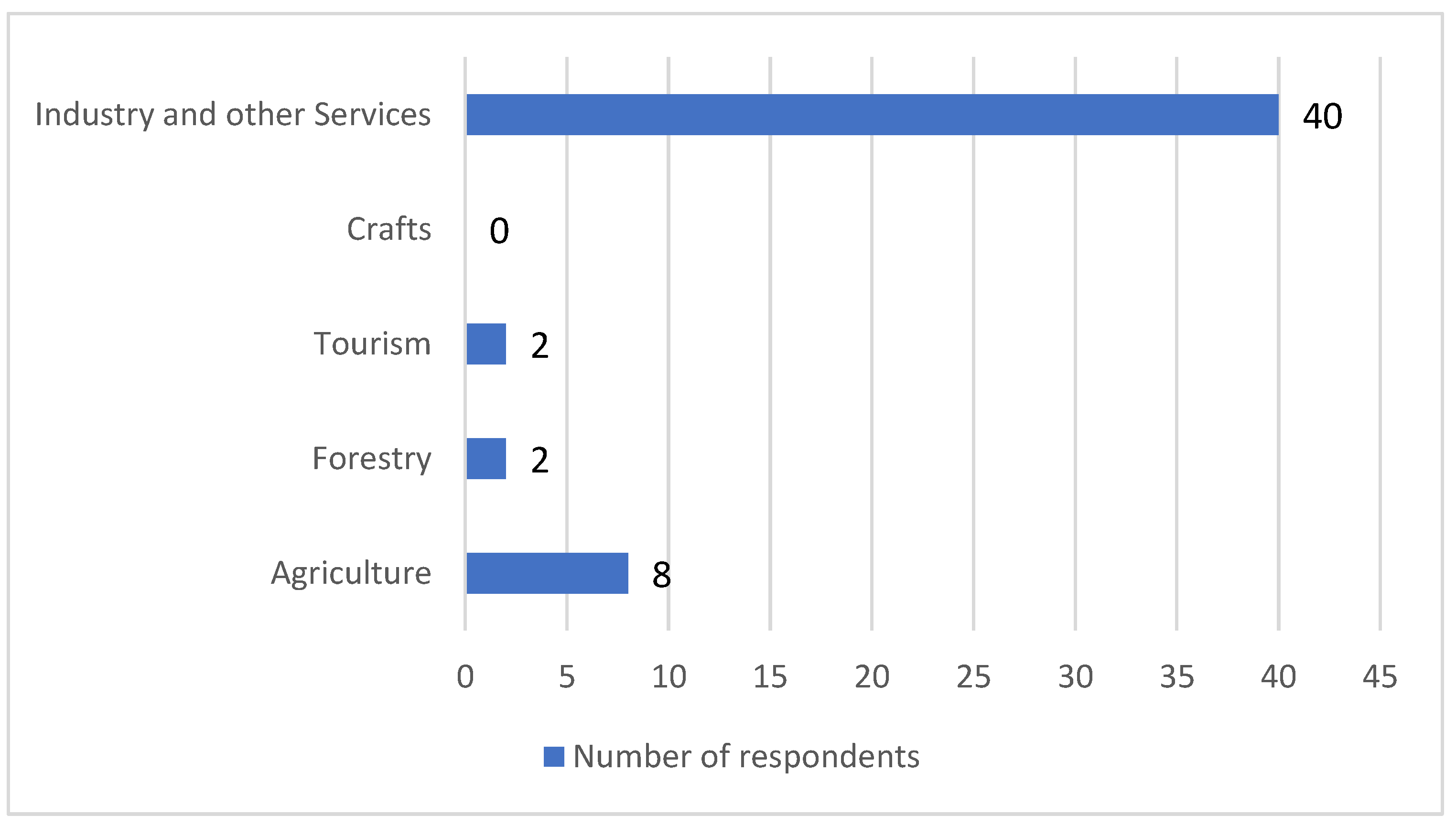

- Agriculture is no longer the main source of income, with the economy returning to industry and other services; this shows that the resident population has exceeded the status of farmers and there is a desire to orient toward other areas, including tourism, even if it does not currently occupy a leading place (Figure 19).

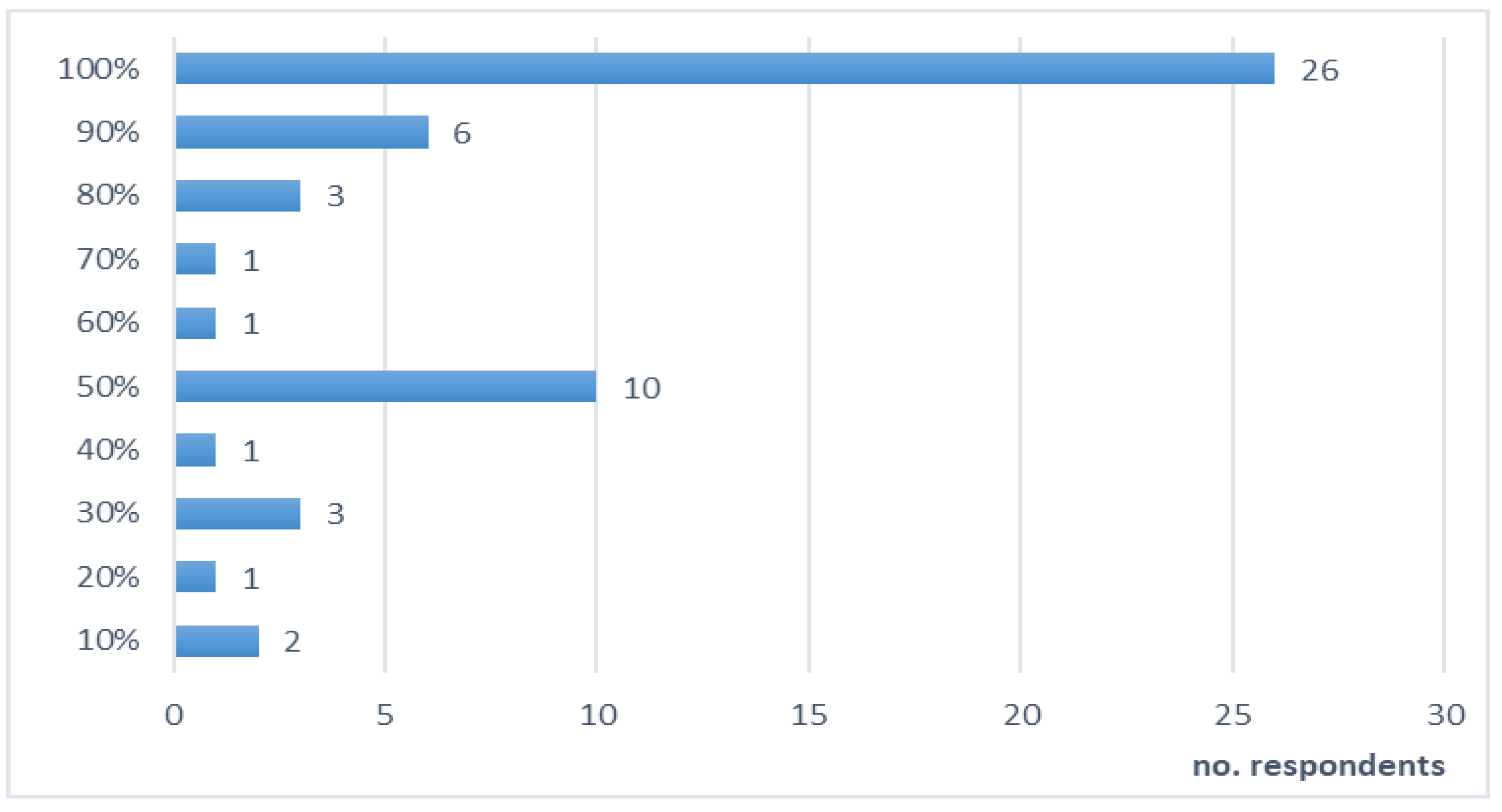

- There exists a high degree of openness (48.1% of respondents) in terms of respondents’ intention to start their own activity in the field of rural tourism (Figure 20).

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Revealing the attractive value of the identified tourist resources that form the current touristic offerings, which can be obtained via an qualitative and quantitative quantification of the resources that compose the natural and anthropic tourism potential of the studied area; therefore, it is necessary to identify all existing tourist resources that have the capacity to support the practice of rural tourism in the mentioned area and to assess their attractive value. This can be achieved using a complex index (Gołembski’s index), based on multivariate comparative analysis, assessing the natural and human-made features and the degree of development of each locality from studied area [104,105]. This would facilitate the value hierarchy of the inventory resources and establish the priorities of the process of tourism development in terms of objectives and tourist locations in the Gurghiului Valley, a process that will be able to complement the current touristic offerings. In this respect, we will focus on qualitative and quantitative investigation of the potentiality of the whole studied area by dividing it into several touristic areas, based on its physiographic setting and Land Use–Land Cover (LULC) features, using satellite image data [106,107]. Additionally, it is important to reveal how to use the spatial distribution of tourism resources and the influencing factors in order to promote the sustainable development of rural tourism and sustain rural revitalization of the local communities from Gurghiului Valley.

- (2)

- Understanding if the effects of choice attributes on rural tourism are important in order to find a way to offer services and products that can appeal to customers via exploration of tourists’ preferences and examination of the individual determinants of these preferences [108].

- (3)

- Evaluating how site attributes affect the choice of a host area or location from the studied area in different tourism markets [109].

- (4)

- The use of discrete choice experiments for measuring and predicting individuals’ preferences and choices of alternatives, and whether these preferences could provide quantitative measures of the relative importance of the attributes of tourism destinations, products, or services, in order to find out tourists’ willingness to pay for various services [110,111].

- (5)

- Exploring tourists’ preferences for various destinations, taking into account the effects of the modernization of the transport network (the increase in accessibility and safety and the decrease in the time needed to access different tourist attractions in the studied area) and if this can contribute to the planning, marketing, management and sustainable development of different types of tourism that can be practiced in the studied area [112].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. 2017 Annual Raport; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419807 (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Winter, P.L.; Selin, S.; Cerveny, L.; Bricker, K. Outdoor recreation, nature-based tourism, and sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Pan, H.; Zheng, S. Tourism development, environment and policies: Differences between domestic and international tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.; Mitra, S.A. Methodology for Assessing Tourism Potential: Case Study Murshidabad District, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2012, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kachniewska, M.A. Tourism development as a determinant of quality of life in rural areas. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes. 2015, 7, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrichi, I. Turism Durabil—o Noua Perspectiva; Pro Universitaria: Bucuresti, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Equipe, M.I.T. Tourismes 1: Lieux Communs; Belin: Paris, France, 2008; 320p. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Geneva, UN-Dokument A/42/427. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B.; Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.L.J. Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25 year bibliometric analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J.; Ricart Casadevall, S. Sustainable Development: Meaning, History, Principles, Pillars, and Implications for Human Action: Literature Review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R. An environmentally based planning model for regional tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: http://www.un"documents.net/our"common"future.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2013).

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Towards innovation in sustainable tourism research? J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, A.-B.; Elazigue, B.D. Opportunities and challanges in tourism development role of local government in Philppines. Papers Presented to 3rd Annual Conference Academi Network Development Studies Asia (ANDA). Skills Development Network Dynamism Asian Development Countries. Under Global Symposium Hall, Nagoya University Japan. 2011, pp. 1–46. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9545190/Opportunities_and_Challenges_in_Tourism_Development_Roles_of_Local_Government_Units_in_the_Philippines (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Moscardo, G. Interpretation and sustainable tourism: Functions, examples and principles. J. Tour. Stud. 1998, 9, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khartishvili, L.; Muhar, A.; Dax, T.; Khelashvili, I. Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataya, A. The Impact of Rural Tourism on the Development of Regional Communities. J. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2021, 2021, 652453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, J. Territorial Planing and Regional Development; Clujeană University Press Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Saghin, D.; Lăzărescu, L.-M.; Diacon, L.D.; Grosu, M. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism: A Decisive Variable in Stimulating Entrepreneurial Intentions and Activities in Tourism in the Mountainous Rural Area of the North-East Region of Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândea, M.; Stăncioiu, F.A.; Mazilu, M.; Marinescu, R.C. The competitiveness of the tourist destination on the future tourism market. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2009, 6, 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Ștefan, D.; Vasile, V.; Popa, A.-M.; Cristea, A.; Bunduchi, E.; Sigmirean, C.; Ștefan, A.-B.; Comes, C.-A.; Ciucan-Rusu, L. Trademark potential increase and entrepreneurship rural development: A case study of Southern Transylvania, Romania. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Mahoney, E.; Butler, L. Understanding the Nature and Extent of Farm and Ranch Diversification in North America. Rural Sociol. 2008, 73, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisiewicz, R. Conditions for Development of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism in the Border Area of the European Union: The Example of the Tri-Border Area of Poland–Belarus–Ukraine. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonescu, D.; Antonescu, R.-M. Dezvoltarea Durabila a Agro-Turismului in Uniunea European si in Romania; MPRA Paper; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2013; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Benedek, J.; Dezsi, Ş. Analiza Socio-Teritorială a Turismului Rural din România din Perspectiva Dezvoltării Regionale şi Locale; Clujeană University Press Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Gao, X.; Wu, R.; Wang, Y.; Choi, B.-R. How Does Sustainable Rural Tourism Cause Rural Community Development? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otiman, P.I. Romania’s current agrarian structure–a great (and unsolved) social and economic problem of the country. Rom. J. Sociol. 2012, 23, 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Florencio, B.; Santos-Roldán, L.; Berbel-Pineda, J.M.; Castillo-Canalejo, A.M. Sustainable Tourism as a Driving Force of the Tourism Industry in a Post-COVID-19 Scenario. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 158, 991–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing Traditional Villages through Rural Tourism: A Case Study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscarelli, R. Slow tourism infrastructure to enhance the value of cultural heritage in inner areas. Cap. Cult. 2019, 19, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, C.; Coros, M.M.; Balint, C. Romanian Rural Tourism: A Survey of Accommodation Facilities. Stud. UBB Negot. 2017, 62, 71–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A.A.M.; Strat, V.A.; Grosu, R.M.; Zgură, I.D.; Anagnoste, S. The Regional Development of the Romanian Rural Tourism Sector. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. 1997. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/rural-tourism (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Ogarlaci, M. Rural Tourism Sustainable Development in Hungary and Romania. Quaestus Multidiscip. Res. J. 2014. Available online: https://www.quaestus.ro/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/ogarlaci4.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Nistoreanu, P.; Ţigu, G.; Popescu, D.; Pădurean, M.; Talpeş, A.; Ţală, M.; Condulescu, C. Ecoturism şi Turism Rural; ASE Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nistoreanu, P. Aprecieri asupra fenomenului touristic rural (Appreciations on the rural touristic phenomenon). J. Tour. Stud. Res. Tour. 2007, 3, 16–23. Available online: http://revistadeturism.ro/rdt/article/view/229 (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Praptiwi, R.A.; Maharja, C.; Fortnam, M.; Chaigneau, T.; Evans, L.; Garniati, L.; Sugardjito, J. Tourism-Based Alternative Livelihoods for Small Island Communities Transitioning towards a Blue Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Sun, B. Influential mechanism of farmers’ sense of relative deprivation in the sustainable development of rural tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C. Future trends in tourism research—Looking back to look forward: The future of ‘Tourism Management Perspectives’. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puška, A.; Šadić, S.; Maksimović, A.; Stojanović, I. Decision support model in the determination of rural touristic destination attractiveness in the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, B.A.; Morrison, A. Tourism Entrepreneurship Research. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2011, 8, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, H. Le Tourisme Rural Dans Les 12 états Membres de la CEE; Direction Générale des Transports; TER: Bruxelles, Belgique, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dezsi, S.; Rusu, R.; Ilies, M.; Ilies, G.; Badarau, S.; Rosian, G. The Role of Rural Tourism in the Social and Economic Revitalisation of Lapus Land (Maramures County, Romania). In Proceedings of the 14th SGEM Geoconference on Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; Limited Liability Company STEF92 Technologies: Sofia, Bulgaria; pp. 783–790. [Google Scholar]

- Trukhachev, A. Methodology for Evaluating the Rural Tourism Potentials: A Tool to Ensure Sustainable Development of Rural Settlements. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3052–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agritourism. Available online: https://agritourism.eurac.edu/ (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Analiza Diagnostic Privind Dezvoltarea Turismului Rural și Agroturismul în Regiunea de Dezvoltare Nord, Ministerul Agriculturii, Dezvoltării Regionale și Mediului, Agenția de Dezvoltare Regională Nord. Available online: http://www.adrnord.md/public/files/ANALIZA-DIAGNOSTIC-turism-Finale1774.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Christou, P.; Farmaki, A.; Evangelou, G. Nurturing nostalgia?: A response from rural tourism stakeholders. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, E.; Vijulie, I.; Manea, G.; Tărlă, L.; Dezsi, S. Changes in the Romanian Carpathian tourism after the communism collapse and the domestic tourists’ satisfaction. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2014, 54, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sonnino, R. For a ‘Piece of Bread’? Interpreting Sustainable Development through Agritourism in Southern Tuscany. Sociol. Rural. 2004, 44, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, S.; Huang, Y. Rural Tourism Development in China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Dean, D.; Chen, B.T.; Kusdibyo, L. Tourist Experience with Agritourism Attractions: What Leads to Loyalty? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, T. Agri-Tourism: An Innovative Supplementary Income-Generating Activity in Rural India. Int. J. Soc. Econ. Res. 2013, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Tzeng, G.-H.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, P.-Y. Improving metro–airport connection service for tourism development: Using hybrid MCDM models. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieș, G. Turismul Rural din România, Modele ale Specificităţii Regionale: Suport Pentru Strategiile de Valorificare Turistică a Satelor Tradiţionale; Clujeană University Press Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Soare, I.; Costachie, S. Ecoturism si Turism Rural, 2nd ed.; Europlus Publishing House: Galati, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coroş, M.M.; Negruşa, A.L. Analiza evoluţiei şi a performanţelor ofertei turistice din România şi din Transilvania. Amfiteatru Econ. 2014, 16, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B. Sustainable Rural Tourism Strategies: A Tool for Development and Conservation. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijijayanti, T.; Agustina, Y.; Winarno, A.; Istanti, L.N.; Dharma, B.A. Rural Tourism: A Local Economic Development. Australas. Account. Bus. Finance J. 2020, 14, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăvan, V. Turism Rural, Agroturism, Turism Durabil, Ecoturism; Economică Publishing House: Bucureşti, România, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Rural Tourism and Sustainability: A Special Issue, Review and Update for the Opening Years of the Twenty-First Century. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Morris, M.H.; Schindehutte, M. Understanding the dynamics of entrepreneurship through framework approaches. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 1–13. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43553075 (accessed on 7 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Okumus, F.; Wu, K.; Köseoglu, M.A. The entrepreneurship research in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Lekovi´c, M.; Joukes, V. A Bibliometric Analysis of Crossref Agritourism Literature Indexed in Web of Science. Hotel Tour. Manag. 2019, 7, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniyar, S.; Awasthi, M.K.; Kapoor, S.; Mishra, A.K. Agritourism: Structured Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Charter for Rural Areas. Available online: http://www.assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewHTML.asp?FileID=7441 (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Buda, D. Agroturismul și rolul autorităților publice în acest sector. Rev. Transilv. De Ştiinţe Adm. 2021, 1, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ceric, D. Overestimating the role of tourism in rural areas on the example of selected regions in Poland and Croatia. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2016, 43, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizler, J. Opportunities for the sustainable development of rural areas in Serbia. Probl. Ekorozw. 2013, 8, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Demonja, D. The overview and analysis of the state of rural tourism in Croatia. Sociol. Prost. 2014, 52, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibănescu, B.C.; Stoleriu, O.M.; Munteanu, A.; Iațu, C. The Impact of Tourism on Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorobantu, M.R.; Nistoreanu, P. Rural Tourism and Ecotourism—The Main Priorities in Sustainable Development Orientations of Rural Local Communities in Romania. Econ. Transdiscipl. Cognit. 2012, 15, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Nistoreanu, P. The ecotourism-element of the sustainable development of the local rural communities in Romania. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2005, 7, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, S. The tourist potential of rural areas in Poland. East. Eur. Countrys. 2011, 17, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhill, S.; Buhalis, D. Introduction: Challenges for tourism in peripheral areas. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F.; Gannon, A. Rural tourism as a factor in rural community economic development for economies in transition. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.D.; Hall, D.R. Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Case Studies; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D. Rural tourism development in Southeastern Europe: Transition and the search for sustainability. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 165–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanescu, B. Consequences of peripheral features on tourists’ motivation. The case of rural destinations in Moldavia, Romania. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2015, 4, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Lisiak, M.; Borowiak, K.; Munko, E. The concept of sustainable tourism development in rural areas—A case study of Zbąszyń Commune. J. Water Land Dev. 2017, 32, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladek, C.; Bodmer, U.; Heissenhuber, A. Vorstellungen potenzieller deutscher Touristen von Urlaubszielen in Ländlichen gebieten Rumäniens und Bulgariens. Tour. J. 2002, 6, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Melichová, K.; Majstríková, L. Is rural tourism a perspective driver of development of rural municipalities?—The case of Slovak Republic. Acta Reg. Environ. 2017, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbalová, M.; Takác, I.; Valach, M.; Tvrdonová, J. Leader-ex-post evaluation of the delivery mechanism/Leader–ex-post hodnotenie implementacného mechanizmu. EU Agrar. Law. 2015, 4, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchta, S. Vývojové trendy vidieckych a mestských oblastí Slovenska. Ekon. Pol’nohospodárstva 2012, 12, 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- Strategia Națională Pentru Dezvoltarea Durabilă a României 2030. Paideia: Bucureşti. 2018. Available online: https://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Strategia-nationala-pentru-dezvoltarea-durabila-a-Romaniei-2030_002.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Stoleriu, O.M.; Ibanescu, B.C. Romania’s country image in tourism tv commercials. In Proceedings of the SGEM 2015 Conference proceedings, Albena, Bulgaria, 18–24 June 2015; pp. 867–874. [Google Scholar]

- Stoleriu, O.M.; Ibănescu, B. Dracula tourism in Romania: From national to local tourism strategies. In Proceedings of the SGEM 2014 Conference on Political Sciences, Law, Finance, Economics and Tourism, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; STEF92 Technology. pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Tudora, D.; Eva, M. A geographical methodology for assessing nodality of a road network. Case study on the Western Moldavia. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2014, 54, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudora, D. Processing territorial data series in calculating the Moldavian rural development index. Geogr. Timisiensis. 2010, 19, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P.; Havadi-Nagy, K.X.; Marosi, Z. Tourism as a driving force in rural development: Comparative case study of Romanian and Austrian villages. Tourism. Int. Interdiscipl. J. 2016, 64, 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Danzberger, J.B. La caza: Un elemento esencial en el desarrollo rural. Mediterr. Econ. 2009, 15, 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rengifo-Gallego, J.I. Un segmento del turismo internacional en auge: El turismo de caza. Cuad. Tur. 2008, 22, 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Heffelfinger, J.R.; Geist, V.; Wishart, W. The role of hunting in North American wildlife conservation. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 70, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghel, M. Valea Gurghiului-Mureș Valea Regilor, O variantă de monografie a Văii Gurghiului. Petru Maior Publishing House: Reghin, Romania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Von Spiess, A.R. Gurghiu—Domeniul Regal de Vânătoare în trecut și astăzi, 2nd ed.; Honterus Publishing House: Sibiu, Romania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Egresi, I.; Kara, F. Motives of tourists attending small-scale events: The case of three local festivals and events in Istanbul, Turkey. Geoj. Tour. Geosites. 2014, 2, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, A.; Hurley, P.D.; Ilies, D.C.; Baias, S. Tourist animation—a chance adding value to traditional heritage: Case study’s in the Land of Maramures (Romania), Revista de Etnografie și Folclor. J. Ethnol. Folk. 2017, 1–2, 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, L.I.U.; Fuying, X. Research on the Driving Force of the Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism in the New Rural Construction. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2010, 38, 2102–2104. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Jamaluddin, M.R.; Zulkifly, M.I. Local community attitude and support towards tourism development in Tioman Island, Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, G.; Sharifzaden, A. Rural residents’ perception toward tourism development: A study from Iran. Int. J. Tourism Res. 2014, 16, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics/(NIS—Institutul National de Statistică/INS. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-tabl (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- National Authority for Tourism (NAT). Authorized Lodgings Database. Available online: http://turism.gov.ro/web/autorizare-turism/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Golembski, G. (Ed.) Regionalne Aspekty Rozwoju Turystyki [Regional Aspects of Tourism Development], 1st ed.; PWN: WarszawaPoznan, Poland, 1999; pp. 1–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A.; Malec, M. Evaluating Local Attractiveness for Tourism and Recreation—A Case Study of the Communes in Brzeski County, Poland. Land 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Mondal, B.K.; Bhadra, T.; Abdelrahman, K.; Mishra, P.K.; Tiwari, A.; Das, R. Geospatial Analysis of Geo-Ecotourism Site Suitability Using AHP and GIS for Sustainable and Resilient Tourism Planning in West Bengal, India. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.K.; Acharya, A.; Nandan, T. Assessing the Geo-Ecotourism Potentiality of West Bengal with Special Reference to its Coastal Region Using Geospatial Technology; Hassan, M.I., Sen Roy, S., Chatterjee, U., Chakraborty, S., Singh, U., Eds.; Social Morphology, Human Welfare, and Sustainability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Alarcón, S. Rural tourism preferences in Spain: Best-worst choices. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 89, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I.; Del Chiappa, G.; Perdue, R.R. International convention tourism: A choice modelling experiment of host city competition. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A. A review of research into discrete choice experiments in tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on Discrete Choice Experiments in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, R.; Franch, M.; Menapace, L.; Cerroni, S. Are tourists willing to pay for decarbonizing tourism? Two applications of indirect questioning in discrete choice experiments. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 65, 1240–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qian, J.; Chen, T.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y. Influence of the High-speed rail on the spatial pattern of regional tourism—Taken Beijing–Shanghai High-speed rail of China as example. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 890–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Pan, B.; Law, R. Machine Learning in Internet Search Query Selection for Tourism Forecasting. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Lou, Y.; Kadoch, M.; Cheriet, M. A Human-Guided Machine Learning Approach for 5G Smart Tourism IoT. Electronics 2020, 9, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crăciun, A.M.; Dezsi, Ș.; Pop, F.; Cecilia, P. Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania). Sustainability 2022, 14, 16295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316295

Crăciun AM, Dezsi Ș, Pop F, Cecilia P. Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania). Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):16295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316295

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrăciun, Andreea M., Ștefan Dezsi, Florin Pop, and Pintea Cecilia. 2022. "Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania)" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 16295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316295

APA StyleCrăciun, A. M., Dezsi, Ș., Pop, F., & Cecilia, P. (2022). Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania). Sustainability, 14(23), 16295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316295