1. Introduction

The topic of the people–place relationship has received considerable attention from both researchers and practitioners in place marketing. Individuals would develop a mental picture of a place, such as a tourism destination or a residential area, through interactions with it over time. The majority of previous studies have typically focused on the concept of destination image, which refers to the sum of beliefs, ideas and impression tourists hold of a tourism destination [

1]. It is consistently found that destination image influences tourists’ destination choice and experiences [

2]. Residents, as one of the most important stakeholders of a city, would also form a mental image of the city, which induces a range of positive outcomes, such as support for tourism development [

3]. While considerable attention has been paid in the past to research issues related to tourists’ destination image, literature on issues of residents’ place image has emerged very slowly [

4].

For tourists, a city is merely a destination for a short stay of several days [

5]. In many cases, tourist revisits are not guaranteed even if they are satisfied with the city [

6]. For residents, the city is more than a destination for holiday. It is also a place where they live, shop, work, socialize, and relax. Compared to tourists, the tourist city has more complex and special meanings for its residents. Therefore, residents’ place image is considered as a complex and multifaceted construct [

4]. Ramkissoon and Nunkoo [

7] found that place image is composed of four dimensions of social attributes, transport attributes, government service attributes, and shopping. Stylidis et al.’s [

4] study shows that place image has four dimensions: physical appearance, community services, social environment, and entertainment opportunities. However, the applicability of these findings to other cities needs to be further examined [

4,

7].

China has undergone rapid urbanization since the reform and opening-up of the Chinese economy in 1978. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in 2019, 60.60% of the China’s population lived in cities [

8]. On the one hand, urbanization has given a strong boost to city tourism, which has become one of the fast-growing travel segments in China [

9]. On the other hand, city tourism has significantly accelerated the pace of urbanization. City residents in China share the advantages brought by urban construction and tourism development and their quality of life has improved significantly.

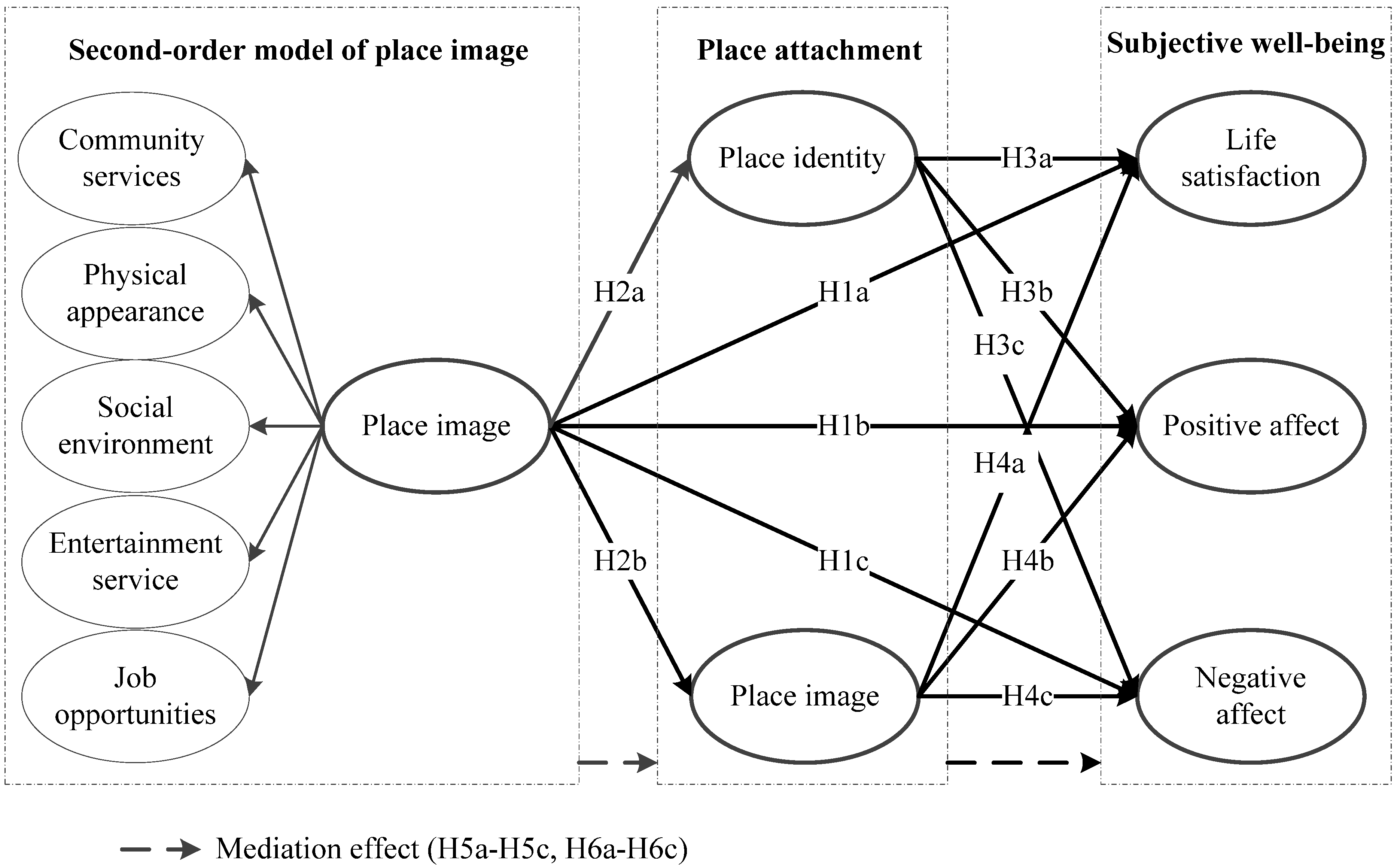

Studying residents’ image of a city provides critical insights for city marketing and development, and for improvement of residents’ subjective well-being [

4]. On the one hand, place image induces a series of positive city-level outcomes, as Stylidis et al. [

3] observed that residents who have positive place image are likely to support tourism development. On the other hand, place image will also lead to several positive outcomes for residents, which has not yet been examined. If the city provides residents with good living, shopping, working, and recreational environments through the improvement of the quality of public services, creation of more jobs, and construction of diversified recreational facilities, residents will have a higher satisfaction with the city in these aspects. According to the bottom-up theory of satisfaction [

10] and affective-cognitive consistency theory [

11], residents with higher levels of satisfaction with specific city attributes will have higher levels of life satisfaction, more positive affect, and less negative affect. In addition, residents develop place attachment to the city because its attributes fulfill their functional and emotional goals. Place attachment, in turn, satisfies residents’ basic needs in terms of belonging, self-esteem, meaning, and sense of control [

12], and thus promotes their subjective well-being. To sum up, this study aims to investigate the effect of place image on residents’ subjective well-being, as well as the mediation effect of place attachment on this relationship.

It is of great significance to examine the impact of residents’ place image on their subjective well-being. At the individual-level, well-being is the purpose for which people engage in all activities, and individuals with higher levels of subjective well-being have better physical and mental health, work efficiency, and social relationships [

13]. How to improve residents’ subjective well-being is a key challenge facing governments at all levels. This study finds a new perspective for improving residents’ subjective well-being, i.e., shaping residents’ positive perception of city attributes. At the city-level, competitions among cities have become increasingly intense as a result of globalization and rapid change of environment [

14]. Cities have to compete with each other for tourists, immigrants, entrepreneurs, and investors. Building a quality living environment that is ideal for living, working, and travelling to improve residents’ place image and subjective well-being becomes a powerful weapon to gain competitive advantage over its competitors. At the societal-level, residents’ well-being is the foundation of a sound society, and a guarantee of its development and prosperity [

15]. The findings of this study provide an effective basis for formulating social policies and monitoring social development in order to build a harmonious society.

6. Conclusions and Discussions

6.1. Conclusions

This study took Guangzhou as an example to examine the relationships among residents’ place image, place attachment, and subjective well-being. Several important conclusions are drawn from this study. Place image describes residents’ perceptions of their city in different attributes [

3]. Previous studies developed different dimensions of place image [

7]. Many cities in China have undergone a significant development and transformation because of market reform and urbanization in the past three decades. Residents’ place image might be different from that of other countries. This study found that job opportunity was also a dimension of residents’ place image, thus suggesting that residents consider economic growth and job availability as important factors influencing their satisfaction with a city.

Place image is found to positively influence residents’ subjective well-being, implying that residents who have positive perceptions of city attributes are likely to have higher levels of life satisfaction, more frequent positive affect and infrequent negative affect. This finding is in accordance with the bottom-up theory of subjective well-being [

10]. A positive place image reflects residents’ higher satisfaction with the city attributes, and therefore contributes their life satisfaction. This finding is also consistent with affective-cognitive consistency theory [

11]. Place image reflects residents’ cognitive evaluation of their living city in community services, physical appearance, social environment, entertainment opportunities, and job opportunities, residents would align their affective states with their cognitions.

Place image has a positive effect on place attachment, which is consistent with previous research that community ties, sense of security, natural, and architectural or urban features are important predictors of place attachment [

44]. Place attachment involves residents’ functional and emotional bonds with their city. Functional attachment stems from the fulfillment of residents’ functional needs by living conditions and personal development environment provided by their living city, such as community services, recreational facilities, and job opportunities [

42]. Emotional attachment derives from residents’ identification and belonging to their city. When residents have higher levels of satisfaction with the city in different attributes, they are more likely to perceive of themselves as a part of the city and use the city to define themselves, and accordingly form a stronger identification with the city [

57].

Place attachment has a positive and significant effect on life satisfaction and positive affect, implying that place identity and place dependence can satisfy residents’ basic psychological needs in belongings, self-esteem, meaning, and sense of control, and thus induces high levels of subjective well-being [

63]. It was found that place identity and place dependence have a negative impact on residents’ negative affect, however these effects are nonsignificant. An explanation is that negative affect is more influenced by negative life events [

79]. Goldstein and Strube [

80] found that success feedback increases positive affect but does not influence negative affect, while failure feedback increased negative affect, but does not influence positive affect. Place attachment is a kind of positive attitude; it is reasonable that it has a positive effect on positive affect but does not have a significant effect on negative affect.

Place attachment mediates the positive impacts of place image on life satisfaction and positive affect. This finding uncovers the underlying mechanism of how place image influences residents’ subjective well-being, which can be explained by the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions [

67]. Favorable living and working environments provide material prerequisites for residents’ quality of life. City serves as a medium for residents to express themselves, and therefore promotes their subjective well-being. Place attachment, which derives from residents’ positive perceptions of city attributes, broadens residents’ thought-action repertoire and builds their personal resources, and therefore leads to their subjective well-being.

6.2. Managerial Implications

City managers can benefit from this study. City managers should attach great importance to the resident’s place image. City managers, for a long time, have narrowly focused on destination image, i.e., how the city is perceived by tourists as a destination. Destination image is undoubtedly important in the field of place marketing, as tourists bring large amount of revenues to the city. However, residents’ place image also needs to be valued. For tourists, the city is just a destination for holiday, while for residents, the city is a place where they live, work, and relax. Therefore, the city has more meanings to residents than to tourist, and residents have a stronger relationship with the city than tourists. Previous studies have consistently confirmed the positive effect of tourists’ destination image [

2], and by analogy, it is predicted that place image can induce a range of positive individual- and city-level outcomes. There is a need for city managers to leverage place image to improve city’s competitive advantage. As our study suggests, place image is composed of community services, physical appearance, social environment, entertainment opportunities, and job opportunities, in order to shape residents’ positive place image, city managers are advised to improve these city attributes, for example, constructing more recreational and shopping facilities, creating more diversified work opportunities, improving the quality of public services, and beautifying the city environment to build a high-quality living environment for residents.

Apart from the construction of the city’s physical and social environments, city managers should strengthen publicity for place image to residents. Residents’ psychological and behavioral responses to the city are based on their perception of what city attributes are, not on the city attributes themselves. It is from this perspective that city managers to actively communicate different city attributes to residents via various channels, such as broadcast media, print media, social media, and outdoor advertising. For example, city managers can communicate the city’s achievements and development plan to its residents to shape their positive place image through which their subjective well-being would be improved.

Since place attachment mediates the positive impact of place image on subjective well-being, city managers can promote residents’ subjective well-being through strengthening their place attachment. On the one hand, city managers can improve the capability of their city in fulfilling residents’ functional goals to improve place dependence. On the other hand, city managers can strengthen the unique features or brand personality of their city to improve place identity. In addition, city managers can also use other strategies, such as improving residents’ familiarity with the city and enhancing their sense of control over the city, to increase residents’ place attachment.

Residents’ role in city branding should be stressed. Residents are one of the most important stakeholders of a city in its development. Previous studies have narrowly considered residents as an element of destination image, for example, whether residents are friendly to tourists, ignoring the fact that residents also hold mental pictures of their city. Residents with a high level of subjective well-being are brand champions who actively spread good words about the city. Therefore, city managers are advised to use residents as an important media to communicate the city brand to its targets, such as tourists, investors, and immigrant.

6.3. Limitations

This research has the following limitations. First, this study only takes Guangzhou as a research site to collect data, since cities differ in their scales, cultures, and economic growth rates, the findings of this study might not be generalized to other cities. Therefore, future researchers can further validate findings of this study using data collected from other cities. Additionally, future studies are encouraged to collect a larger sample to validate the findings of this study. Second, residents’ place image is a complicated concept, whereas this study treated it as a cognitive construct, i.e., perception of different city attributes. Future studies could further examine whether emotional and behavioral dimensions can also be included in the concept. Third, compared to destination image, empirical research on place image is scarce, and more studies are needed to investigate its outcomes, such as place citizenship behavior. Finally, residents’ subjective well-being may be influenced by other factors, such as income, and future studies may include these factors in the model as control variables to further examine the effect of place image on residents’ subjective well-being.

_Chen.png)