Abstract

Corporate ethics is an important part of corporate sustainable development. Sustainability is not only about the environment but also about the well-being of employees, including job satisfaction (JS), the Psychological contract (PC), etc. Among them, to organize relationships with other stakeholders, the unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB) of employees not only damages the corporate image and reputation but even threatens the sustainable development of the enterprise. In this context, the influencing factors that induce UPB should be analyzed and considered. Based on social exchange theory and social cognitive theory, this research explores how idiosyncratic deals (I-deals) affect employees’ intention to perform UPB through the PC and JS from the viewpoint of employee-organization relationships, and the moderating role of environmental turbulence in it. The research sample was drawn from 377 employees working in China, manufacturing companies. The questionnaire was distributed at two time points. In the first questionnaire, the employees who participated in the survey answered information such as idiosyncratic deals, the PC, JS and environmental turbulence (ET). After 1 month, employees responded to UPB messages. The research hypotheses were tested analytically using SPSS 23.0 and Amos 23.0. The survey showed that I-deals had a beneficial impact on UPB. The psychological contract and JS also mediated the influence on I-deals on UPB. The positive relationship between I-deals and UPB through the chain mediated effect of PC and JS. Moreover, ET positively moderates the relationship between I-deals and UPB, the higher the ET, the stronger the relationship between I-deals and UPB. Conversely, the lower.

1. Introduction

With rapid economic growth, people experience positive changes brought about by the business society to their lives but also the negative news of corporate moral deficiency events that can damage the external reputation of the organization (e.g., Uber, Japan steel, Volkswagen and Melamine). However, some are still hidden inside the organization [1]. The problem of corporate ethics has become a common phenomenon and threatens the sustainable development of enterprises, so corporate moral crisis has attracted much attention. Unethical behavior is generally described as any behavior that is “illegally or morally unacceptable in the wider society” [2], and it can happen to anyone in the organization, from the managed to the manager.

Some scholars believe that employees violate social values, moral standards and laws not for self-seeking or revenge but for the organization’s and its members’ interests; such altruistic unethical behavior is called unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB) [3,4]. However, the exposure of unethical behavior will not only deteriorate the partnership between the company and other stakeholders but also harm the business’s external reputation. As a result, employees who behave unethically have been a long-standing subject of research in management and organizations. Moreover, the existing literature has found that both positive reciprocity and organizational identity promote UPB [5]. Therefore, the academic community has begun to reflect on the reasons why employees engage in unethical activities that are usually viewed as positive management measures, employee attitudes or behaviors [6].

Alternatively, as the core of an enterprise’s core competitiveness, employees are the soul and key resources of the enterprise’s foothold and development. With the advancement of globalization, the increasingly open labor market liberalization, employees’ employment ability for the negotiations among employees and organizational relationships, dramatic changes have taken place in organization in the role of employee career management by the controller into supporters; this presents significant challenges for organizations to retain professional employees. Therefore, idiosyncratic deals (I-deals) that adapt to the needs of employee and organization employment negotiation emerge at the right moment and become a new topic in the field of employee and organization relationship research [7]. In this context, this paper studies the I-deals for suspected organizations on the influence of unethical behavior; however, the existing research mainly from the individual character, moral case characteristics and the point of view of leadership behavior, to employees’ organizational wrongdoing to explain the connection between the two studies, is still lacking from the viewpoint of the relationship between the employee and the organization as well as the potential impact. To address these issues, we examine the mediatory functions of the Psychological contract (PC) and job satisfaction (JS) to explain the complex relationship between I-deals and pro-organizational unethical behavior.

Firstly, PC refers to “employees perceive each other’s responsibilities in the employment contract” [8]. When employees and organizations perceive cognitive differences in the PC, they will prompt each other to sign personalized contracts. However, employees maybe conduct unethical behaviors in order to achieve high performance goals matching personalized contracts [7]. Secondly, JS of employees is impacted in varying degrees by various I-deal kinds [9]. Employees receive more benefits from the organization the higher the JS. Therefore, on the one hand, the organization is more eager to obtain the employee’s return when it satisfied the needs of the employees [10,11], and, on the other hand, employees may be more focused on how to repay the benefits the organization brings to them than on their own ethical behavior [4]. Career progress, personal growth and psychological safety are often the basis of a PC, which causes high commitment of some employees to the organization. On this basis, employees who obtain I-deals are likely to have a higher sense of satisfaction and then take some immoral actions in return for the organization. Therefore, I-deals also indirectly generate UPB through the PC-JS pathway. In addition, whether the organization can dynamically change and adapt to the environment is essential to the long-term growth of the organization. If the employees with idiosyncratic deals cannot adapt to the speed of environmental changes, the organization may cancel the I-deals, and, in this case, the employees are likely to carry out immoral behaviors. Therefore, to comprehend the mechanisms underlying the effects of I-deals on UPB better, this study further examined the regulating function of environmental turbulence (ET).

This paper explores four issues with the use of social exchange theory and social cognitive theory. The first is the relationship between I-deals and UPB. Secondly, the mediating role of PC and JS in the relationship is discussed. Thirdly, in this study investigation, the chain mediating effect of PC and JS on the relationship between I-deals and UPB is explored. Finally, the moderating influence on ET on the relationship between I-deals and pro-organizational unethical behavior is tested.

2. Review of the Literature and Formulation of Hypotheses

2.1. Idiosyncratic Deals (I-Deals) and Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior (UPB)

I-deals are voluntary, non-standard, individualized agreements negotiations between specific employees and employers for mutual gain to all parties [12]. As an employee incentive agreement, it helps organizations retain valuable employees by developing personalized work mechanisms that meet employee needs and preferences [13]. Although special working conditions are specially formulated for employees, at the same time, the organization will also put forward high-performance goals for employees that match the personalized work mechanism [14,15]. Once they fail to accomplish the high-performance goals set by the organization, they will not only face negative self-evaluation but also lose the support of the leadership and possibly even their jobs.

Social cognitive theory also points out that when people achieve their goals, in addition to external material rewards, they will also generate internal self-motivation, such as positive self-evaluation and self-satisfaction, and when the goal cannot be achieved, there will be a corresponding psychological burden [16]. Therefore, in order to avoid the psychological burden and negative consequences of not being able to meet the requirements, or to maintain the employment relationship with the organization, employees will adopt some unconventional ways to achieve the high performance brought by I-deals’ requirements. There is a high likelihood of triggering unethical behavior, but helpful work efficiency, because this kind of behavior or method not only helps employees to obtain a positive self-evaluation by reducing their psychological burden but also obtains opportunities for self-growth in the organization and is even more conducive to the long-term development of their own careers.

Based on social exchange theory [17,18], the reciprocal social exchange mechanism is believed to play a crucial role in motivating employees to participate in UPB [3,4,19,20,21]. UPB refers to unethical behavior that is deliberately performed by employees and violates the social moral code but is beneficial to the organization [4]. UPB includes illegal or violating social norms and values [2,4]. Although UPB is a pro-organizational behavior that is not formally required in the job description, employees perform these behaviors specifically to help the organization. A study found [22] that when faced with unattainable work goals, employees often resort to unethical means rather than just doing their best. Therefore, when employees fail to achieve high-performance goals that match the I-deals, employees will face losing the support of the organization and its leaders, or even cancel the I-deals. However, in order to gain the support of the organization and its leaders, employees may improve high performance by engaging in unethical behavior in order to achieve mutual benefits between the organization and employees. Based on the above analysis, we developed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

I-deals have a positive effect on UPB.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Contract

The psychological contract is seen as a clause, on the one hand, the conditions offered by employers to employees and their acceptance, reducing employee dissatisfaction and employment security through optimal wages, which in turn affect job performance [23,24]. On the other hand, the PC is considered by employees to undertake special obligations, but it can lead to a high degree of work commitment and loyalty while obtaining job security, which affects innovation and high-performance goals [25]. At the same time, the PC is an expression of the mutual obligations of the employee and the organization and is based on the belief that the relationship of mutual trust and loyalty between them is based on a relational PC of long-term employment [8]. As a result, employees are likely not only to care about specific and short-term economic goals in the setting of personal work goals, but they also will pay more attention to long-term development goals and have a stronger awareness of personal development orientation under the influence of organizational goals. On the other side, employees have an accurate perception of what the organization needs to undertake [26], while the organization also holds a sense of identification with the employee in a long-term employment relationship [27,28,29]. Therefore, they are more aware of the benefits of unethical behavior; they are freed from the shackles of morality in order to maintain good relations with the organization [30,31] and consider UPB as an effective way and means [18].

Moreover, I-deals not only affect the performance and evaluation of the PC over time [32,33] but also are inflection points affecting changes in the PC. When accepting challenging tasks, employees with I-deals with special values can generate new obligations in the organization or provide greater contributions through individuals [34,35]. Meanwhile, some scholars pointed out [36] that the core of the PC is the obligation to give back to both parties. The PC between employees and the organization not only affects the cognition of each other but also leads to the generation of I-deals due to the difference between these cognitions and the original cognition. In addition, when the organization promises a future to employees with I-deals, there is a stronger negative correlation between the degree of PC destruction and organizational commitment [37]. It can be seen that I-deals, like formal legal contracts, will be used to define the employment relationship between the employee and the organization, and thus affect the PC of both parties. Furthermore, the organization provides benefits to employees and their families [38], which will lead to employees wanting to give back to the organization. Under the care and support of the organization, it is easy for employees to mistake UPB approved by the organization. It is hypothesized, based on these arguments, that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Psychological contracts mediate the relationship between I-deals and UPB.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction refers to the psychological state of employees who have positive or negative views and attitudes about the organization or other related fields [39,40]. Studies show that flexible I-deals for working hours can not only generate more intrinsic motivation for employees and promote career development but also enhance JS [41]. At the same time, due to the achievement of I-deals, especially the achievement of I-deals in advance, the dependence between employees and the organization is enhanced, which is obviously helpful to improve employees’ job autonomy and JS. On the basis of social exchange theory [18], reciprocity means that both parties have obligations and expectations of privacy [42]. The more benefits employees receive from the organization, the higher the JS. Therefore, on the one hand, the organization is more eager to obtain rewards from employees when it meets their needs [10,11], and, on the other hand, employees may be more focused on how to repay the benefits brought to them by the organization than whether their own behavior conforms to the ethical standards [4]. It is, therefore, hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between I-deals and UPB.

2.4. The Chain Mediating Role of Psychological Contract and Job Satisfaction

According to social exchange theory, the employment relationship and PC are essentially a kind of social exchange; that is, while individuals contribute to the organization, they also expect the organization to give corresponding rewards [43]. Studies show that if an organization is able to fulfill the organizational responsibility in the PC, employees’ work motivation, JS and job performance will be improved [44,45]; at the same time, the JS with the social exchange will follow the principle of reciprocity, that “when one party benefits from the other, responsibility also accompanies it” [46]. Social exchange theory also implies a win-win exchange relationship between the organization and individual [47]; career advancement, personal growth and psychological safety are often the foundations of a PC that elicits some employees’ high commitment to the organization, and employees who receive I-deals are likely to have a higher sense of satisfaction on this basis, and then take some unethical behaviors for the purpose of rewarding the organization. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The psychological contract and job satisfaction play a chain mediating role in the relationship between I-deals and UPB.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence

Environmental turbulence refers to the speed of environmental change and the degree of uncertainty it faces [48], and is perceived by the organization but cannot accurately assess the impact of the external environment or future changes [49]. ET is divided into variability and predictability, and is a combination of changes in the market environment. To be accurate, variability represents the novelty and speed of changes in the environment, and predictability refers to the accuracy and decision-making ability of a business or organizations when dealing with changes in information [50]. Social cognitive theory believes that individual behavior is influenced by the interaction of individual and environmental factors, and can predict individual behavior through individual factors’ perception of the environment [51,52], I-deals need to take into account the interests of both the organization and employees, and I-deals with developmental characteristics are conducive to the long-term career development of employees [53]; when ET is higher, in order to fulfill the intention of career development and the high performance goals stipulated in the I-deals, employees may implement unethical behaviors, thinking that this is for the survival and development of their own organizations. Therefore, ET affects the relationship between I-deals and UPB.

In addition, whether the organization can dynamically change and adapt to the environment is the key to the sustainable development of the organization [54]. In the face of ET and change, organizations not only need to re-identify and learn new knowledge, but also need to adjust and adapt within a certain period of time. If employees with I-deals cannot adapt to the speed of environmental change or achieve matching goals, there will be corresponding negative effects. For example, the effect of promoting organizational performance may be diminished or even the organization may cancel I-deals, in which case employees are more likely to act unethically. In line with this reasoning, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Environmental turbulence positively moderates the relationship between I-deals and UPB. That is, when environment turbulence is high, the positive impact of I-deals on UPB will be stronger than when it is low.

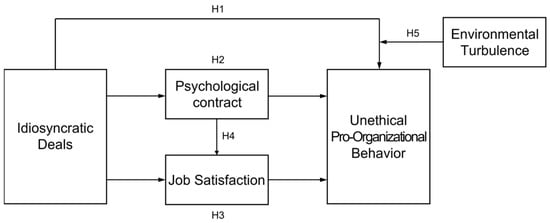

Based on the above study, the research model was set as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

In order to test the proposed hypothesis, managers of 15 manufacturing firms were contacted to send a questionnaire to some of their employees. Firms included five automotive firms, five furniture firms and five food firms. Data were gathered using common method bias and a self-administered online survey; the questionnaire was distributed at two points in time, a one-month interval in the process of collecting data. In the first questionnaire, participating employees answered information on the independent variable idiosyncratic trading, the mediating variables PC and JS and the moderating variable ET. One month later, employees answered information questions on the dependent variable UPB. A total of 500 questionnaires were administered; 123 invalid questionnaires were excluded due to inconsistent or missing responses, and 377 valid questionnaires were returned. The respondents’ gender was almost evenly distributed. In total, 51.9% of the respondents were male; 48% were female; 83.7% were under 40 years; 53.8% were bachelor; and 53.2% of those who worked for the firm for more than five years. The demographics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The questionnaire utilized a Likert five-point scale, with all questions rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), except for gender (1 = male, 2 = female), age (1 = under 25 years, 2 = 26–30 years, 3 = 31–40 years, 4 = 41–50 years, 5 = above 51 years), formal degrees (1 = high school and below, 2 = college, 3 = bachelor, 4 = master and above) and work years (1 = under 3 years, 2 = 3–5, 3 = 6–8, 4 = 9–11, 5 = 12 and above).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 377).

3.2. Measures

Rousseau and Kim’s 4-item unidimensional I-deals scale [55] was used to evaluate whether employees have opportunities for training, job skills development, work activities and career development that differ from their colleagues. One of the items on this scale is “I have different work activities than my colleagues”. Dabos and Rousseau’s 7-item PC scale [56] was used to measuring employees’ accountability to the organization. A sample item from the scale is “only perform specific research activities for which I am compensated”. Yelin Shin and others’ 4-item JS scale [57] was used to evaluate satisfaction with the work environment and the job itself. One of the items on the scale is “I am satisfied with the working environment at my company”. Umphress and others’ 6-item UPB scale [4] was used, e.g., “If it helped my organization, I would distortion of facts to make the organization look good”, “If it would benefited my organization, I would withhold negative information about my company or its products from customers and clients”. Miller and others’ 5-item ET scale [58] was used, e.g., “The extent to which the technological development of the company’s product or service has changed”. Given that demographic characteristics such as age, work years and other individual difference variables have an impact on UPB and may influence our hypotheses [3], gender, age, formal degrees and work years of employees were introduced as control variables in our analytical model for this study.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 presents the mean, standard deviations, and correlations for a variety of I-deals, PC, JS, ET and UPB. The correlational findings indicate that the I-deals variable was positively correlated with the PC (r = 0.461, p < 0.001), JS (r = 0.445, p < 0.001) and UPB (r = 0.449, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the PC was positively correlated with JS (r = 0.564, p < 0.001). Besides, ET was also positively correlated with UPB (r = 0.184, p < 0.001). Hence, H1, H2 and H3 were preliminarily supported.

Table 2.

Correlation analysis value of main variable.

4.2. Formatting of Mathematical Components

To evaluate the scale’s validity and dependability, we utilized confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 23.0 and principal component analysis (PCA) using SPSS 23.0. Reliability was tested primarily through composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (α). Table 3 showed that the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient and CR for the main variables I-deals, PC, JS, UPB and ET were in the range of 0.822–0.906, which is above the recommended value of 0.70, and therefore have good reliability.

Table 3.

Calculation model validation.

Validity tests are carried out in two aspects: convergence validity and discrimination validity. The primary goal of the convergent validity test is to determine whether the theoretical framework and actual measurement data are compatible, as evidenced by the factorial cross-loadings to evaluate each loading’s statistical significance and the magnitude of the average variance extracted (AVE) values, with larger AVE values indicating higher reliability and convergence of the items’ reliability. Cross-loadings between the measured data and latent variables in this study were all greater than 0.60 (see Table 3), and the AVEs were all greater than 0.55, all of which met the requirements for convergent validity, demonstrating once more the scale’s high validity used in this research.

At last, Harman’s single factor test was employed to examine common method bias [59]. The most important of the five factors accounted for only 34.9% of the variance, indicating that none of the overall variance emerged as a common factor. Therefore, our results were unaffected by common method bias.

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

In order to verify our hypothesis, we employed SPSS 23.0. Table 4 displays the outcomes. The Models 1, 3 and 6 contain the control variables of gender, age, degrees and work years. Models 2, 4 and 7 introduce effects of I-deals, and Models 5, 8, 9 and 10 introduce the mediating influence on PC and JS. Finally, Table 5 checks the potential modifying effects of ET.

Table 4.

Findings from the mediation analysis.

Table 5.

The moderating effect on environmental turbulence.

As show in Table 4, I-deals were closely associated with UPB (M7, β = 0.457, p < 0.001). Thus, H1 was supported. To test the mediating role of the PC, we used the criteria proposed by Baron and Kenny [60]. The PC was closely associated with employees’ UPB (M8, β = 0.400, p < 0.001). After entering the PC, the influence of I-deals on employees’ UPB grew weaker; however, the impact was still felt (M8, β = 0.268, p < 0.001). This implied that the PC serves as a partial mediator in the relationship between I-deals and UPB. To demonstrate this result further, we performed an indirect effect test using the method of Preacher and Hayes [61]. The outcomes are displayed in Table 6; the mediating role of the PC was significant (indirect effect = 0.130, SE = 0.028, 95% CI [0.077, 0.186]). Therefore, H2 was confirmed.

Table 6.

Mediated model: direct, indirect and overall effects.

In addition, I-deals were also positively related to JS (M9, β = 0.430, p < 0.001). After entering JS, the influence of I-deals on employees’ UPB decreased, but the effect was still important (M9, β = 0.263, p < 0.001). Consistently, the results in Table 6 further demonstrate that the indirect effect of I-deals on UPB through JS was also significant (indirect effect = 0.086, SE = 0.019, 95% CI [0.367, 0.547]). Therefore, H3 was confirmed.

Finally, it can be determined from Table 6 that the serial mediating effect of I-deals on UPB through the PC and JS pathway was also significant (indirect effect = 0.059, SE = 0.014, 95% CI [0.034, 0.089]). Therefore, H4 was also confirmed.

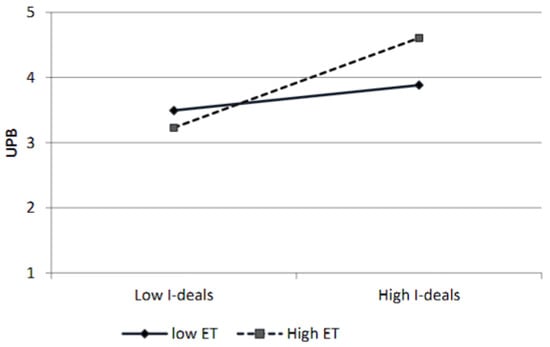

H5 predicts that ET will moderate the relationship between I-deals and UPB such that, as ET rises, the favorable relationship will be strengthened. As shown in Table 5, we first entered the control variables (gender, age, degrees, work years), followed by the variable of I-deals, and the ET moderator variable at Model 3, and I-deals–ET interaction was entered in Model 4. The findings revealed that the interaction between I-deals and ET was a positive connection with UPB (M4, β = 0.247, p < 0.001), thus confirming H5. To investigate the interaction’s nature, in accordance with ET, we plotted the slope of I-deals on UPB (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, the higher the ET, the stronger the relationship between I-deals and UPB.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the regulatory influence on ET on the relationship between I-deals and UPB.

5. Discussion

Based on social exchange theory and social cognitive theory, this paper discusses the influence of I-deals on employees’ UPB. The results of this study confirm that I-deals had a significant effect on building the PC and increasing JS and contribute to the occurrence of UPB. The PC and JS mediated the relationship between I-deals and UPB. ET positively moderated the relationship between I-deals and employees’ UPB.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution and Practical Implication

The following are theoretical developments and influences of this study.

First, this study successfully links I-deals with UPB, revealing that employees with I-deals generate unethical behaviors in order to maintain corporate image and improve corporate interests. Previous scholarly research focused more on the positive aspects of the impact of social exchange, such as the role of I-deals in promoting job performance, organizational citizenship behavior and employees’ innovation behavior [62,63,64], and disregard the negative effects of social exchange. This study found that employees with I-deals would perform unethical behavior in order to achieve matching high-performance goals, which may be beneficial to the enterprise in the short term but will eventually cause serious damage to the enterprise’s market reputation and development prospects [22]. This has an enlightening effect on the theoretical research of perfecting the I-deals and the management practice of the targeted intervention of employees’ UPB. It is hoped that the academic circle will further consider and explore the moral impact of favorable attitudes and behaviors to enterprises, provide more abundant and powerful theoretical results and promote enterprises to prevent unethical behaviors more effectively.

Second, as a result of the literature review, most of the preceding studies on employees’ UPB were conducted in terms of individual characteristics [4,65] or relationships [21,66]; however, not much attention has been paid to the ways in which strategic human resource management practices influence employees’ UPB. Strategic human resource management is the most direct and intimate source of contact between companies and their employees, so UPB by employees often occurs in specific management practices at the corporate level. Solutions implemented by organizations and managers can inhibit employees’ unethical behavior but at the same time can induce employees’ UPB. Therefore, this study discusses how unusual and critical transaction systems can induce unethical behavior for the benefit of the organization by providing more benefits to employees. In addition, it responded to the previously studied method of preventing UPB by employees and further studied the factors that induce UPB by employees.

Then, this study explains the intrinsic mechanism of I-deals and employees’ UPB based on the social exchange theory from the perspective of the reciprocity principle, proposing the mediating variables of I-deals affecting employees’ UPB: PC and JS. It was also found that employees who entered into I-deals committed beneficial but UPB in order to establish and maintain the PC in return for the organization. The “employee-centered” idiosyncratic work system that is designed not only facilitates the achievement of organizational goals but also helps employees to achieve their own development goals and to realize the common good and strengthens the PC between employees and the organization. At the same time, the more benefits employees receive from the organization, the higher their JS; employees may be more focused on how to repay the benefits of the organization than whether their behavior is ethical. With reference to previous research by scholars, the mediating mechanism of UPB has been explained using social exchange theory [4,67], and no research has tested the mediating role of the PC and JS in this process as well as the chain mediating role. So, this research contributes by selecting two variables that have not received much attention in the past but have the potential to build long-term mutually beneficial relationships with companies, namely the PC and JS, uncover the mechanism of I-deals’ influence on employee’s UPB and retest the explanation of social exchange theory for UPB.

Lastly, this study investigates ET as a moderating variable, affecting the happening of unethical pro-organization behaviors. Based on social exchange theory, UPB may occur due to individual or environmental factors. Thus, this study incorporated ET as a research framework for the impact of I-deals on employees’ UPB and considered the combination of personal and environmental factors that affect the occurrence of employees’ unethical behavior. The findings of this study can be helpful to obtain a more detailed picture of the factors influencing pro-organizational behavior; it also provides theoretical suggestions for corporate management of such behaviors. Therefore, companies should strengthen the importance of ethical goals in the face of competition and at the same time strengthen the ethical management system within the company to encourage ethical leadership behavior [68], strengthen employees’ moral awareness and call on employees to use ethical practices to achieve high-performance goals that match their I-deals to achieve the sustainable development of the companies.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

This research has the following limitations and needs to be supplemented through further study. First of all, this research collected data from different perspectives but still has a problem that causal conclusions cannot be drawn. In the cause of improving this, it is necessary to provide an experimental method for later causality verification. Secondly, the PC and JS, and the study has limitations. In order to have a more systematic and comprehensive understanding of the UPB induced by employees with I-deals in terms of social cognitive variables, the relationship between the two can be further explored in the future by using the regulatory focus theory as the basis for variables such as moral disengagement or moral identity. Furthermore, this research explored the relationship between I-deals and UPB based on social cognitive theory, and future research could further explore the effect of various I-deal kinds on employees’ UPB. Finally, this study thinks that the phenomenon of I-deals that will bring about UPB should be common in business society; data were only collected from the China context. In the future, it is necessary to collect and verify data from each country, and research on unethical behavior and UPB will be conducted by presenting variables such as culture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and X.L.; methodology, Y.H.; software, Y.H.; validation, Y.H. and X.L.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, Y.H., S.N. and J.K.; data curation, Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.; visualization, J.K. and Y.H.; supervision, S.N.; project administration, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wonkwang University (protocol code: WKIRB-202211-SB-108; date of approval: 11 November 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kelebek, E.E.; Alniacik, E. Effects of Leader-Member Exchange, Organizational Identification and Leadership Communication on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: A Study on Bank Employees in Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B. When Employees Do Bad Things for Good Reasons: Examining Unethical Pro-Organizational Behaviors. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B.; Mitchell, M.S. Unethical behavior in the name of the company: The moderating effect of organizational identifification and positive reciprocity beliefs on unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.C.; Sheldon, O.J. Relaxing moral reasoning to win: How organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liang, J. High performance expectation and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Social cognitive perspective. Acta Psychol. 2017, 49, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiq, J.; Duanj, Y.; Fant, W. A New Perspective of Researching the Relationship Between Employee and Organization: Idiosyncratic Deals. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 1601. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M. Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1989, 2, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.C.; Slater, D.J.; King, T.; King, A. Measuring Idiosyncratic Work Arrangements: Development and Validation of the Exposti-deals Scale. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2008, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Batchelor, J.H.; Seers, A.; O’Boyle, E.H., Jr.; Pollack, J.M.; Gower, K. What does team-member exchange bring to the party? A meta-analytic review of team and leader social exchange. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 35, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.S.; Sin, H.P.; Conlon, D.E. What about the leader in leader-member exchange? The impact of resource exchanges and substitutability on the leader. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Ho, V.T.; Greenberg, J. I-Deals: Idiosyncratic Terms in Employment Relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M. Idiosyncratic deals: Flexibility versus fairness? Organ. Dyn. 2001, 29, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Las Heras, M.; Rofcanin, Y.; Matthijs Bal, P.; Stollberger, J. How do flexibility i-deals relate to work performance? Exploring the roles of family performance and organizational context. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1280–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luksyte, A.; Spitzmueller, C. When are overqualified employees creative? It depends on contextual factors. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Justice in Social Exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, W.; Merritt, S.M. Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior and Positive Leader–Employee Relationships. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 168, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effelsberg, D.; Solga, M. Transformational leaders’ in-group versus out-group orientation: Testing the link between leaders’ organizational identification, their willingness to engage in unethical pro-organizational behavior, and follower-perceived transformational leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effelsberg, D.; Solga, M.; Gurt, J. Transformational leadership and follower’s unethical behavior for the benefit of the company: A two-study investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, M.E.; Ordóñez, L.; Douma, B. Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Understanding organizational behavior. Homewood, Illinois: The Dorsey Press. Soc. Force. 1960, 40, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.S.; Tekleab, A.G. Taking stock of psychological contract research: Assessing progress, addressing troublesome issues, and setting research priorities. Employ. Relatsh. Exam. Psychol. Context. Perspect. 2004, 253, 283. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292265017_Taking_stock_of_psychological_contract_research_Assessing_progress_addressing_troublesome_issues_and_setting_research_priorities (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Lee, K.Y.; Kim, S. The effects of commitment-based human resource management on organizational citizenship behaviors. The mediating role of the psychological contract. World J. Manag. 2010, 2, 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.B.; Hom, P.W.; Tetrick, L.E.; Shore, L.M.; Jia, L.; Li, C.; Song, L.J. The norm of reciprocity: Scale development and validation in the Chinese context. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, A.; Vandenberghe, C.; Camerman, J. The role of justice and social exchange relationships in workplace deviance: Test of a mediated model. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 1687–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lin, X.; Hu, W. How followers’ unethical behavior is triggered by leader-member exchange: The mediating effect of job satisfaction. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2013, 41, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, I.M.; Schreurs, B.; Mohammed, S.J. How and when LMX quality relates to counterproductive performance: A mediated moderation model. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. J. Polit. Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, J.R. Lying and Deception: A Behavioral Model. In Negotiating in Organizations; Bazerman, M.H., Lewicki, R.J., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, S.; Rousseau, D.M. Psychological contracts and idiosyncratic deals: Mapping conceptual boundaries, common ground, and future research paths. In Riding the New Tides: Navigating the Future through Effective People Management; Bhatt, P., Jaiswal, B., Majumdar, B., Verma, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: New Delhi, India, 2017; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tomprou, M.; Rousseau, D.M.; Hansen, S.D. The psychological contracts of post-violation survivors: A post-violation model. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; De Cooman, R.; Mol, S.T. Dynamics of psychological contracts with work engagement and turnover intention: The influence of organizational tenure. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, R.; Roe, R.E. Towards a dynamic model of the psychological contract. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2007, 37, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Is the Psychological Contract Worth Taking Seriously? J. Organ. Behav. 1998, 19, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Breaches of Past Promises, Current Job Alternatives, and Promises of Future Idiosyn-cratic Deals: Three-way Interaction Effects on Organizational Commitment. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1463–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, D.M.; Rodwell, J.J. Lack of symmetry in employees’ perceptions of the psychological contract. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K.; Nie, Y.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, Y.Z. The relationship between self-control, job satisfaction and life satisfaction in Chinese employees: A preliminary study. Work 2016, 55, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M. Introductory comments: Antecedents of emotional experiences at work. Motiv. Emot. 2002, 26, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, S.; Rousseau, D.M.; Weigl, M.; Müller, M.; Glaser, J. Rede signing work through idiosyncratic deals. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 23, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Bommer, W.H.; Liden, R.C.; Brouer, R.L.; Ferris, G.R. A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1715–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.; Neil, C. Exchange relationships: Examining psychological contracts and perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katou, A.A.; Budhwar, P.S. The Link Between HR Practices, Psychological Contract Fulfillment, and Organizational Performance: The Case of the Greek Service Sector. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, C.; Schalk, R. Implications of differences in psychological contracts for Human Resources Management. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, H.P. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Kong, H. Research on the impact of idiosyncratic deals on Chinese employee job satisfaction and affective commitment. Soft Sci. 2016, 30, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F.J. Three types of perceived uncertainty about the environment: State, effect, and response uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I. Strategic Management; Macmillan: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 3, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. I-Deals, Idiosyncratic Deals Employees Bargain for Themselves; ME Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, A. Strategy and Structure; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Kim, T.G. When Workers Bargain for Themselves: Idiosyncratic Deals and the Nature of the Employment Relationship. In Proceedings of the British Academy of Management Conference, Belfast, UK, 12–14 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dabos, G.E.; Rousseau, D.M. Mutuality and reciprocity in the psychological contracts of employees and employers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Choi, J.O.; Hyun, S.S. The Effect of Psychological Anxiety Caused by COVID-19 on Job Self-Esteem and Job Satisfaction of Airline Flight Attendants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two models of strategic momentum. Strateg. Manag. J. 1982, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.I.; Hu, J. Detecting common method bias: Performance of the Harman’s single-factor test. ACM SIGMIS Database Database Adv. Inf. Syst. 2019, 50, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Zhou, J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Schwarz, G.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Newman, A.; Yu, J.; Xu, L. The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Linear or curvilinear effects? J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 641–653. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Z. Research on the Relationship Between High-Commitment Work Systems and Employees’ Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: The Moderating Role of Balanced Reciprocity Beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 776904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).