Impact of Organizational Culture on Academics’ Readiness and Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes in Kuwaiti Universities during COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Importance of eLearning for Higher Education Institution Sustainability

2.2. Organizational Culture

2.3. Individual Readiness for Change

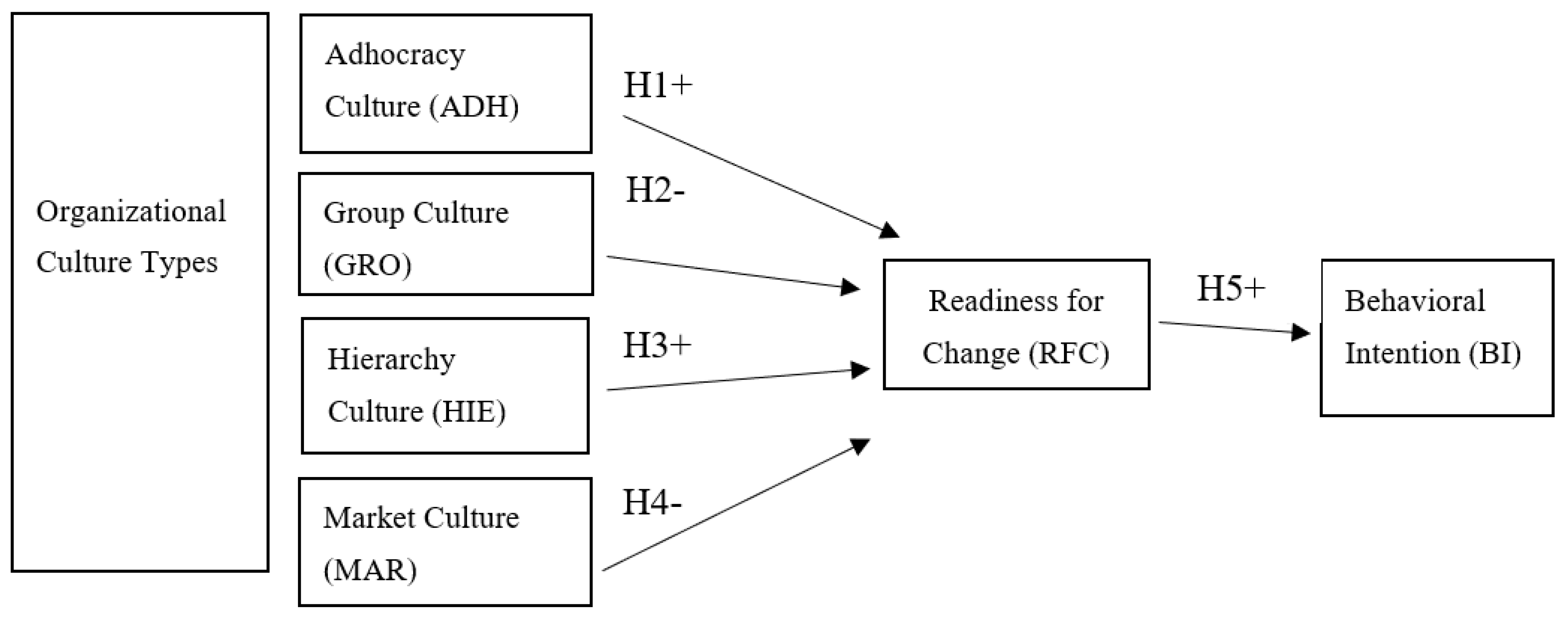

2.4. Organizational Culture Types and Readiness for Change

2.4.1. Adhocracy Culture

2.4.2. Group Culture

2.4.3. Hierarchy Culture

2.4.4. Market Culture

2.4.5. Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes

2.4.6. The Impact of Readiness on Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Analysis and Results

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Multiple Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Theoretical Contribution

6. Empirical Implications

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alismaiel, O.A. Using Structural Equation Modeling to Assess Online Learning Systems’ Educational Sustainability for University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P.A. COVID-19 and emergency eLearning: Consequences of the securitization of higher education for post-pandemic pedagogy. Contemp. Secur. Policy 2020, 41, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, K.; Singh, G.; O’Donoghue, J. Implementing eLearning Programmes for Higher Education: A Review of the Literature. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2004, 3, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Edelhauser, E.; Lupu-Dima, L. Is Romania Prepared for eLearning during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-H. Sustainable Education through E-Learning: The Case Study of iLearn2.0. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalat, M.M.; Hamed, M.S.; Bolbol, S.A. The experiences, challenges, and acceptance of e-learning as a tool for teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic among university medical staff. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Ahmed, A. COVID-19: University Students in the UAE Exempted from Academic Warnings and Dismissals. Retrieved 27 April 2020. Available online: https://gulfnews.com/uae/covid-19-university-students-in-the-uae-exempted-from-academic-warnings-and-dismissals-1.71090887 (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Alhouti, I. Education during the pandemic: The case of Kuwait. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2020, 5, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, K. Middle East-Mobile Infrastructure and Mobile Broadband. Retrieved 13 May 2020. Available online: https://www.budde.com.au/Research/Middle-EastMobile-Infrastructure-and-Mobile-Broadband?r=51 (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Almuraqab, N. Shall Universities at the UAE Continue Distance Learning after the COVID-19 Pandemic? Revealing Students’ Perspective. 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7366799/ (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Palier, B.; Azoulay, R.; Louër, L. Kuwait’s Welfare System: Description, Assessment and Proposals for Reforms; [Research Report] 18; Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AlAjmi, M. The impact of digital leadership on teachers’ technology integration during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kuwait. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 112, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, A. Professional learning communities for educators’ capacity building during COVID-19: Kuwait educators’ successes and challenges. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- AlTaweel, D.; Al-Haqan, A.; Bajis, D.; Al-Bader, J.; Al-Taweel, M.; Al-Awadhi, A.; Al-Awadhi, F. Multidisciplinary academic perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffar, M.; Al-Karaghouli, W.; Ghoneim, A. An empirical investigation of the influence of organizational culture on individual readiness for change in Syrian manufacturing organizations. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2014, 27, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.H.; Abedelrahim, S. Organizational culture assessment using the competing values framework (CVF) in public universities in Saudi Arabia: A case study of Tabuk university. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.D.; Chong, S.C.; Ismail, H. Organisational culture: An exploratory study comparing faculties perspectives within public and private universities in Malaysia. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2011, 25, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.I.; Hill, M.M. Organisational cultures in public and private Portuguese universities: A case study. High. Educ. 2008, 55, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartell, M. Internationalization of Universities: A University Culture-Based Framework. High. Educ. 2003, 45, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.K.; Dinh, H.; Nguyen, H.; Le, D.-N.; Nguyen, D.-K.; Tran, A.C.; Nguyen-Hoang, V.; Nguyen Thi Thu, H.; Hung, D.; Tieu, S.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: An Online Survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.A.; Balmer, M.; Charlton, W.; Ewert, R.; Neumann, A.; Rakow, C.; Schlenther, T.; Nagel, K. Predicting the effects of COVID-19 related interventions in urban settings by combining activity-based modelling, agent-based simulation, and mobile phone data. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, A.; Abbasi, A.S.; Muneer, S.; Qadri, M.M. Organizational Culture and Performance of Higher Educational Institutions: The Mediating Role of Individual Readiness for Change. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfoodh, H.; AlAtawi, H. Sustaining Higher Education through eLearning in Post COVID-19. In Proceedings of the 2020 Sixth International Conference on e-Learning (econf), Sakheer, Bahrain, 6–7 December 2020; pp. 361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kizilcec, R.; Reich, J.; Yeomans, M.; Tingley, D. Scaling up behavioral science interventions in online education. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14900–14905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, C.A.; Paschia, L.; Nicolau, N.L.G.; Stanescu, S.G.; Stancescu, V.M.N.; Coman, M.D.; Uzlau, M.C. Sustainability Analysis of the E-Learning Education System during Pandemic Period—COVID-19in Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smircich, L. Concepts of Culture and Organizational Analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Othman, I. Relationship between Organizational Resources and Organizational Performance: A Conceptualize Mediation Study. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, T. A study of the correlation between service innovation, organizational culture, and organizational performance in the biochemistry industry. Eurasia J. Biosci. 2020, 14, 5507–5514. [Google Scholar]

- Heilpern, J.; Nadler, D. Implementing Total Quality Management: A Process of Cultural Change Organizational Architecture; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Adil, M.S. Impact of Leader’s Change-Promoting Behavior on Readiness for Change: A Mediating Role of Organizational Culture. J. Manag. Sci. 2014, 1, 112–149. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsen, A.; Nilsen, E.; Smedsrud, S.; Kamaric, D. Sustainable development through commitment to organizational change: The implications of organizational culture and individual readiness for change. J. Workplace Learn. 2021, 33, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, C.; Åström, S.; Kauffeldta, A.; Helldinc, L.; Carlströmd, E. Culture as a predictor of resistance to change: A study of competing values in a psychiatric nursing context. Health Policy 2013, 114, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E. Beyond Rational Management: Mastering the Paradoxes and Competing Demands of High Performance; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Haffar, M.; Al-hyari, K.A.; Djebarni, R.; Al-shamali, A.; Abdul Aziz, M.; Al-shamali, S. The myth of a direct relationship between organizational culture and TQM: Propositions and challenges for research. TQM J. 2021, 34, 1395–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Schulte, M. A configural approach to the study of organizational culture and climate. In The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture; Schneider, B., Barbera, K.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 532–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R.; Spreitzer, G.M. Organizational culture and organizational development: A competing values approach. Res. Organ. Chang. Dev. 1991, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, F.; Isakovic, A. Examining the impact of organizational culture on trust and career satisfaction in the UAE public sector: A competing values perspective. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 1036–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, G.; Scrima, F.; Parry, E. The effect of organizational culture on deviant behaviors in the workplace. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2482–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, S.; Mustafa, M. Applying competing values framework to Jordanian hotels. Antolia 2021, 33, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrio, A. An Organizational Culture Assessment Using the Competing Values Framework: A Profile of Ohio State University Extension. J. Ext. 2003, 41, 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Armenakis, A.; Harris, S.; Mossholder, K. Creating Readiness for Organizational Change. Hum. Relat. 1993, 46, 681–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Griffiths, A. The impact of organizational culture and reshaping capabilities on change implementation success: The mediating role of readiness for change. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Chatterjee, D. Impact of culture on organizational readiness to change: Context of bank M&A. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 28, 1503–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.J.; Cooke, R.A.; Lopez, Y. Firm culture and performance: Intensity’s effects and limits. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.; Adams, D.; Russell, J.; Gaby, S. Perceptions of Organizational Readiness for Change: Factors Related to Employees’ Reactions to the Implementation of Team-Based Selling. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.T.; Armenakis, A.A.; Field, H.S.; Harris, S.G. Readiness for organizational change: The systematic development of a scale. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2007, 43, 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M. Employees’ attitudes toward organizational change: A literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalits, A.H.; Kismono, G. Organizational culture types and individual readiness for change: Evidence from Indonesia. Diponegoro Int. J. Bus. 2019, 2, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzwa, D.; Mierzwa, D. Organisational culture of higher education institutions in the process of implementing changes–case study. J. Decis. Syst. 2020, 29, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumijati, A. 6th International Conference on Community Development (ICCD 2019). Published by Atlantis Press. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 2019. Volume 349. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/article/125919114.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Pomyalova, V.O.; Volkova, N.V.; Kalinina, O.V. Effect of the University organizational culture perception on students’ commitment: The role of organizational identification. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 940, 012099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Wu, N. A Review of study on the competing values framework. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Zhu, X.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qin, C. The development and adoption of online learning in pre-and post-COVID-19: Combination of technological system evolution theory and unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassafi, M.O. E-learning intention material using TAM: A case study. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 61, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F.; Mohd Rasdi, R.; Rami, A.; Razali, F.; Ahrari, S. Factors Determining Academics’ Behavioral Intention and Usage Behavior Towards Online Teaching Technologies During COVID-19: An Extension of the UTAUT. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P.; Khan, A.; Tabash, M.I.; Anagreh, S. Teachers’ intention to continue the use of online teaching tools post COVID-19. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8, 2002130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendrati, H.A.; Mangundjaya, W. Individual Readiness for Change and Affective Commitment to Change: The Mediation Effect of Technology Readiness on Public Sector. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwahk, K.Y.; Lee, J.N. The role of readiness for change in ERP implementation: Theoretical bases and empirical validation. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhanisa Radian, N.; Mangundjaya, W.L. Individual Readiness for Change as Mediator between Transformational Leadership and Commitment Affective to Change. J. Manaj. Aset Infrastruktur Fasilitas 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somadi, N.; Salendu, A. Mediating Role of Employee Readiness to Change in the Relationship of Change Leadership with Employees’ Affective Commitment to Change. Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst. J. 2022, 5, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mangundjaya, W.; Gandakusuma, I. The Role of Leadership & Readiness for Change to Commitment to Change. 2013. Available online: http://www.rebe.rau.ro/RePEc/rau/journl/WI13S/REBE-WI13S-A18.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult GT, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partialleast Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Güngör, S.; Şahin, H. Organizational Culture Types that Academicians Associate with Their Institutions. Int. J. High. Educ. 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

| Factor | Cronbach’s Alpha | Rho_A | C.R. | A.V.E. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADH | 0.877 | 0.921 | 0.913 | 0.723 |

| GRO | 0.924 | 0.946 | 0.939 | 0.721 |

| HIE | 0.805 | 0.820 | 0.884 | 0.717 |

| MAR | 0.821 | 0.832 | 0.893 | 0.737 |

| ERFC | 0.870 | 0.876 | 0.907 | 0.661 |

| BI | 0.888 | 0.902 | 0.931 | 0.818 |

| Basis | Categories | F | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 99 | 45.4 |

| Female | 119 | 54.6 | |

| Age | 21–30 | 20 | 9.2 |

| 31–40 | 91 | 41.7 | |

| 41–50 | 81 | 37.2 | |

| 51 and above | 26 | 11.9 | |

| Education | Bachelor’s | 43 | 19.7 |

| Master’s | 64 | 29.4 | |

| Doctorate | 111 | 50.9 | |

| Employment | Private University | 119 | 54.6 |

| Public University | 99 | 45.4 | |

| Academic rank | Instructor | 79 | 36.2 |

| Adjunct | 23 | 10.6 | |

| Assistant Professor | 73 | 33.5 | |

| Associate professor | 21 | 9.6 | |

| Professor | 22 | 10.1 | |

| Experience | 1–5 years | 68 | 31.2 |

| 6–10 years | 35 | 16.1 | |

| 11–15 years | 50 | 22.9 | |

| 16–20 years | 40 | 18.3 | |

| 21 years and above | 25 | 11.5 |

| Org. Culture | GRO | ADH | MAR | HIE | ERFC | BI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRO | — | |||||

| ADH | 0.764 *** | — | ||||

| MAR | 0.637 *** | 0.689 *** | — | |||

| HIE | 0.606 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.424 *** | — | ||

| ERFC | 0.234 *** | 0.209 ** | 0.341 *** | 0.328 *** | — | |

| BI | 0.28 *** | 0.208 ** | 0.441 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.74 *** | — |

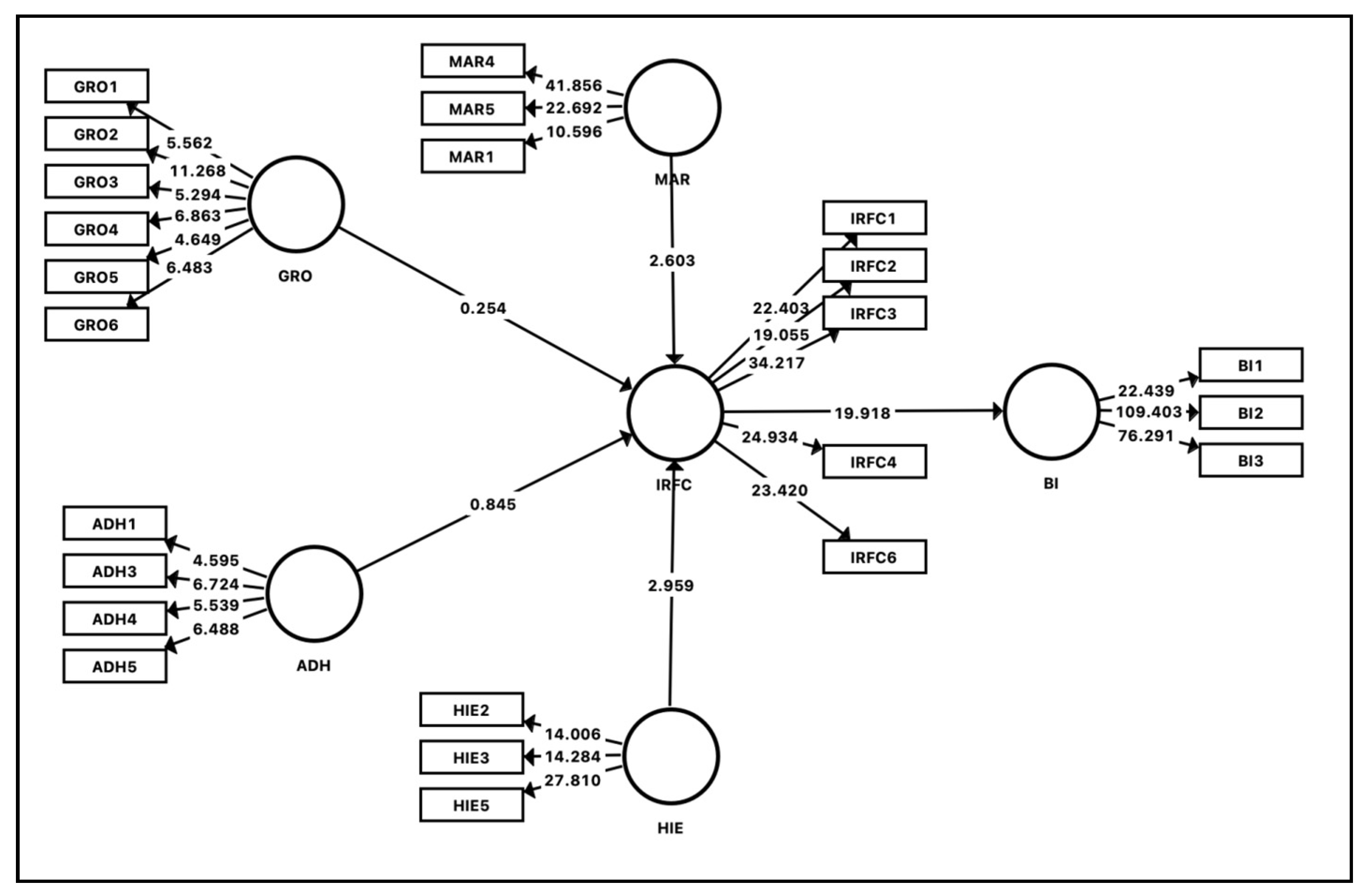

| Hypothesis | Path | β | Standard Deviation | t-Value | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Relationship | H1 | ADH → ERFC | −0.138 | 0.164 | 0.845 | 0.399 | Not Supported |

| H2 | GRO → ERFC | −0.034 | 0.136 | 0.254 | 0.8 | Not Supported | |

| H3 | HIE → ERFC | 0.292 | 0.099 | 2.959 | 0.003 | Supported | |

| H4 | MAR → ERFC | 0.329 | 0.126 | 2.603 | 0.01 | Supported | |

| H6 | ERFC → BI | 0.751 | 0.038 | 19.918 | 0 | Supported | |

| Indirect Relationship | H5.1 | ADH → ERFC → BI | −0.104 | 0.125 | 0.83 | 0.407 | Not Supported |

| H5.2 | GRO → ERFC → BI | −0.026 | 0.102 | 0.254 | 0.799 | Not Supported | |

| H5.3 | HIE → ERFC → BI | 0.219 | 0.073 | 2.992 | 0.003 | Supported | |

| H5.4 | MAR → ERFC → BI | 0.247 | 0.101 | 2.452 | 0.015 | Supported | |

| Private Universities (n = 119) | Public Universities (n = 99) | Total (n = 218) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRO | 0.0241 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.0) | |

| Range | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | |

| ADH | 0.0071 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) | |

| Range | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | |

| MAR | <0.0011 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.0) | |

| Range | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | |

| HIE | 0.1771 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.0) | |

| Range | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | |

| ERFC | 0.0481 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.9 (0.8) | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.8 (0.9) | |

| Range | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | |

| BI | 0.0781 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (0.8) | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.9 (0.9) | |

| Range | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Shamali, S.; Al-Shamali, A.; Alsaber, A.; Al-Kandari, A.; AlMutairi, S.; Alaya, A. Impact of Organizational Culture on Academics’ Readiness and Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes in Kuwaiti Universities during COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315824

Al-Shamali S, Al-Shamali A, Alsaber A, Al-Kandari A, AlMutairi S, Alaya A. Impact of Organizational Culture on Academics’ Readiness and Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes in Kuwaiti Universities during COVID-19. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315824

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Shamali, Sarah, Ahmed Al-Shamali, Ahmad Alsaber, Anwaar Al-Kandari, Shihanah AlMutairi, and Amer Alaya. 2022. "Impact of Organizational Culture on Academics’ Readiness and Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes in Kuwaiti Universities during COVID-19" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315824

APA StyleAl-Shamali, S., Al-Shamali, A., Alsaber, A., Al-Kandari, A., AlMutairi, S., & Alaya, A. (2022). Impact of Organizational Culture on Academics’ Readiness and Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes in Kuwaiti Universities during COVID-19. Sustainability, 14(23), 15824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315824