Abstract

Although public private partnerships (PPPs) have been in existence for decades as a procurement tool for infrastructure projects, a dearth of studies on ex-post evaluation of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects (PPPIPs) exists globally. Additionally, the contribution of scholars to the inclusion of social dimensions in ex-post evaluations is not fully known. Due to the existing gap, this study aimed at identifying and mapping the literature on the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs and reviewed its contribution to the assessment of social impacts through the inclusion of social dimensions. The Arkesy and O’Malley five-stage framework was used to conduct a scoping review grounded in 27 articles focusing on the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs. The selection of articles for review used the PRISMA framework and data were analysed through content analysis. The key findings revealed that mutual relationships existed among the theoretical foundation of the review, the themes, and identified social dimensions. Additionally, diversity was seen in the needs and interests of stakeholders, and finally, the low research output in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs was observed. A huge research potential has been revealed with specific focus on the social dimension of the triple bottom line concept of sustainable development to achieve PPPIPs’ social sustainability.

1. Introduction

Public private partnerships (PPPs) are a procurement tool that have been adopted globally to mitigate funding deficits for development budgets in both developed and developing countries. They have been in existence for decades [1], however, regardless of their use for decades, there is a dearth of studies on the ex-post evaluation of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects (PPPIPs) globally [2], and the contribution of scholars to the inclusion of social dimensions in ex-post evaluation is not fully known.

Social dimensions in infrastructure projects fall along the triple bottom line (TBL) concept of sustainable project development [3], which contends that sustainability can only be attained through an interconnected operation of all the constituent factors, summing up the concepts of economic, environmental, and social. Furthermore, the concept stresses the criticality of not only the economic aspect as it is the focus of most sustainability discourses, but also the social aspect due to the expectation that projects must impact society in a positive way. Although such is the case, the social dimension has not been given much attention in both the literature and practice, as a result, this has negatively affected the attainment of social sustainability in projects [4]. The inclusion of social dimensions supports the evaluation of the social impacts of PPPIPs, which is critical in safeguarding the interests of stakeholders through a sustainable approach [5].

Stakeholders in PPPIPs are underpinned by stakeholder theory, which is a derivative of corporate social responsibility theory. Stakeholder theory is diverse with different methodologies and approaches as such there has been biased focus on only project beneficiaries while neglecting those who might equally affect or be affected by the project [6]. Due to the prevailing skewed focus, a stakeholder approach through a utilitarian strategy was adopted to review the inclusion of social dimensions in the ex-post evaluation methodologies of PPPIPs. This strategy focuses on considering deliberate actions by project organisations that can enhance the welfare of communities [7].

Extending the above notion to the issues under consideration in the present review, communities are regarded as stakeholders in PPPIPs and are bound to be affected by the social impacts of projects implemented within their boundaries. As such, they are integral, first as beneficiaries of PPPIPs, and second as a group capable of exerting a positive or negative impact on projects [6]. Due to their intrinsic inclusion in PPPIPs, the interests or impacts of stakeholders, whether economic, environmental, or social, cannot be neglected. Therefore, the inclusion of social dimensions is critical to support the ex-post evaluation of the social impacts of PPPIPs’ on stakeholders. Moreover, the results from an ex-post evaluation can act as a springboard for best practice and guide policy direction on stakeholder issues in PPP infrastructure projects [8,9].

Defining ex-post evaluation, ref. [10] states that it is the performance measurement of a project to ascertain if it has delivered the intended outcomes. Ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs has gradually gained momentum, particularly in the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and China.

The focus of ex-post evaluation in the UK was on assessing the rates of return [11] and evaluating the economic case for private finance initiative (PFI) projects in NHS hospitals [12]. Further on, ref. [13] conducted an evaluation of PPP funding in Scottish schools where it was found that banks financing private parties showed antagonism towards risk. Although the UK has conducted some ex-post evaluations as highlighted, they were economic with no consideration for the social factors.

In Australia, ex-post evaluation was conducted by [14] on the evaluation of the operational performance of PPP school projects, and [15,16] on “future-proofing” Australia’s PPPs. However, the above scholars highlighted the challenges with the existing PPPIP ex-post evaluation in Australia. For example, ref. [16] expressed dissatisfaction with the constant use of time and cost as parameters for ex-post evaluation of PPPs while [15] recognised the need for intuitive information during ex-post evaluations to formulate performance measures that can “future-proof” Australia’s public sector assets. For Australia, a weak link between the existing ex-post evaluations and consideration of the social dimensions was seen as assessment of the social impacts was disregarded.

Similarly, for China, although significant experience is documented with PPP projects spanning almost three decades, there is little to learn from these projects due to a lack of robust performance evaluation [17]. A few evaluation studies exist though, like the assessment of the public’s satisfaction of the treatment of an urban water environment using a weighted index evaluation system [18]. The focus of the assessment was on the riparian zone with evaluation indices on leisure facilities, greening, complaint management, water quality, leisure perception, and sanitation of the environment. However, the attention of the evaluation leaned towards environmental impacts and was devoid of social impacts.

Additionally, ref. [19] conducted a performance evaluation of renovated residential units using the 4Es (Efficiency, Economic, Effectiveness, and Equity) through a quantitative performance evaluation index system. However, it is worth noting that the evaluation index system was deficient in social dimensions that could be used to assess the social impacts in the ex-post evaluations of PPPIPs.

Furthermore, ref. [20] developed a phase-oriented evaluation framework that had eight evaluation facets. Zooming in on the eight evaluation facets proposed, it was observed that only project externality analysis espoused aspects considering the contribution of PPPIPs to regional social sustainability. Project externalities focus on the impact of the project on society and the economy, which include the creation of employment, a boost in local industries, pollution due to noise and ineffective waste management, and impact on agricultural land because of urbanisation. The other seven aspects had no consideration for social dimensions.

Overall, the background revealed a recurring theme in the existing ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs in Australia, the UK, and China, which puts the social leg in the TBL concept as a neglected dimension in sustainable project development discourse. The existing neglect poses a challenge in assessing the social impacts of PPP infrastructure projects. These observations are supported by increased concerns on the disregard of the social dimension in the sustainable development of construction projects [4,21,22].

1.1. Social Dimensions in Ex-Post Evaluation of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects

Social dimensions in PPPIPs exist under the umbrella of the triple bottom line (TBL) concept of sustainable development [3]. The question of why social dimensions in PPPIPs might arise and a plausible response are provided by [4], who affirmed the concept of construction projects as social components, hence the need to make a positive impact in the societies they are implemented. By extension, it is imperative that the social impacts of PPPIPs to stakeholders, whether positive or negative, are known, although they are neglected and are third in line, lagging behind economic and environmental issues [4]. However, such objectives can only be achieved if the social dimensions are considered in ex-post evaluations. Furthermore, the inclusion of social dimensions is essential since they enable the consideration of social welfare impacts in PPP evaluation to obtain comprehensive results that can guide policy direction and offer improvements in the PPP discourse [8,9].

1.2. Dearth of Studies on Ex-Post Evaluation of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects

Regardless of the use of PPPs for decades, there is a dearth of studies on PPPIP ex-post evaluation globally [23]. The prevailing paucity of literature has exposed gaps in the PPP evaluation methods and are documented by several authors. For example, ref. [14] bemoaned the lack of common approaches in conducting the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs and [24] supported their observations by highlighting the non-existence of a prescribed method in ex-post evaluations. Furthermore, ref. [25] documented the absence of unique performance measurement frameworks for individual PPP types. Therefore, the lack of a common methodology to anchor sustainable ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs can be extended to the neglect of social dimensions.

The neglect of social dimensions in PPPIP ex-post evaluation was also noted in the current EPEC report for 2018. They conducted an ex-post assessment of 29 international PPP case studies in Australia and the United Kingdom due to the maturity of their PPP markets [26]. However, conspicuously missing from their ex-post evaluations were social impacts. Their focus was on performance audits, policy review, assessing value for money, financial risk, operational performance, cost and time overruns, and the effectiveness of the PPP procurement option, among others [26].

Additionally, studies in PPPIP ex-post evaluation were conducted by [2,14,15,16] in Australia [12,13,27], in the UK [17,18,19,20], and in China, among others. However, although these studies focused on various evaluation aspects such as time, cost, quality, and life-cycle evaluation approaches, and proposing comprehensive evaluation frameworks, there was little regard for social dimensions such as their inclusion in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs is not fully known, hence the need for a scoping review.

The objective of this review was to identify and map literature on ex-post evaluation of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects and review its contribution to the assessment of social impacts through the inclusion of social dimensions. Furthermore, the review aimed to answer the following question: What types of social dimensions are included in existing ex-post evaluations of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects? The identified and mapped literature was used to ascertain whether it might be sufficient to pose specific questions that can be adequately addressed through a future systematic review on the evaluation of social impacts of operational Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects.

2. Limitations

The review did not assess the contribution of the identified social dimensions in the evaluation of the social impacts of PPPIPs due to a lack of commonality in their inclusion and the diversity of evidence provided.

3. Materials and Methods

Several purposes exist for undertaking a scoping review, and these are supported by [28]. They outlined four objectives, namely, (1) assessing the scope of existing research on a particular topic; (2) identifying and mapping the literature; (3) exposing gaps in the extant literature; and (4) providing a synopsis and communicate research outcomes. However, ref. [29], while agreeing with all of the above objectives, outlined understanding the conceptual definitions as a springboard for future systematic reviews as additional purposes for conducting scoping reviews. The objective of this scoping review was underpinned by [28] as objective number 2 and [29] had the objective of providing a springboard for future systematic reviews, hence reinforcing the need for a scoping review. Further, a methodological framework for scoping reviews was used [28] incorporating the recommendations proposed by [30]. The stages followed are outlined below:

- Stage 1: Identifying the research question;

- Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies;

- Stage 3: Study selection;

- Stage 4: Charting the data;

- Stage 5: Collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

3.1. Identification of the Research Question

The dearth of literature on the social dimensions in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs influenced the research question. Due to the criticality of social dimensions in the ex-post evaluations of PPPIPs, it was significant to identify and map the literature on the type of social dimensions included in PPPIP ex-post evaluations. The authors in [5] buttress the need for sustainable PPP project performance evaluation through the incorporation of all the dimensions in the TBL concept. The call for the adoption of all three legs in the TBL concept during PPPIP evaluation supports the need for the inclusion of social dimensions in the ex-post evaluation of PPP infrastructure projects, as such, the review had a key research question for direction.

3.2. Identification and Selection of Studies

An iterative process guided by [30] involving searching two databases (Scopus and Web of Science) was conducted from May to June 2022. The inclusion criteria were that articles had to be peer-reviewed and published in the English language. No time restrictions were imposed due to the dearth of literature on PPP ex-post evaluation. A further guideline for the exclusion of studies was topical areas that did not focus on infrastructure projects. However, some of the search terms did not include the term “infrastructure” to capture PPP studies in construction. To afford credibility to the results, the search string results are presented in Table 1 to allow for replicability as guided by [31].

Table 1.

Summary of the search strategy.

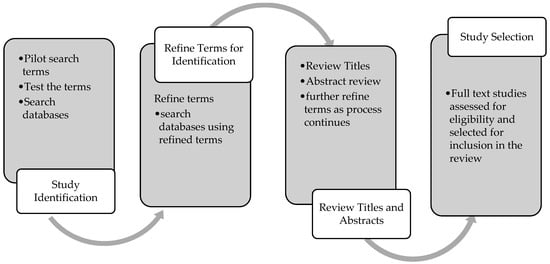

To increase the dependability of the results, in [29,30], the search was conducted by a team of three authors who piloted the search terms and sought their improvement throughout the review process. Duplicates were identified and removed manually. The study titles and abstracts were reviewed further to underpin the relevance of full-text articles selected for inclusion (Figure 1). Disagreements in the selection of studies were resolved through a discussion between the two researchers to reach an agreement. In the event of failure to agree on certain issues, a third senior and experienced researcher was consulted. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) was used for guidance in identifying, screening, and reporting the iterative process of selecting the studies (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Iterative process of identification and the selection of studies adapted from [28,30].

3.3. Charting the Data

A charting table was developed with guidance from the JBI methodology and Arksey and O’Malley framework for scoping review [28,32] and recorded the following information relevant to the research question:

- Author(s);

- Year of publication;

- Origin/country of origin (where the study was published or conducted);

- Aims/purpose;

- Design;

- Type of social dimensions included.

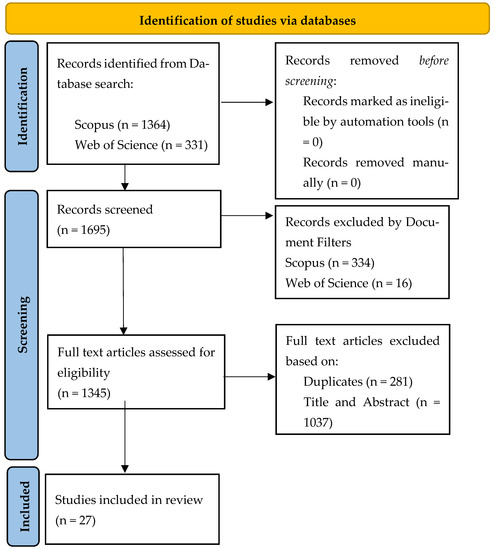

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram [33].

To achieve dependability of the results, two researchers were responsible for developing the data charting table. The table was tested on five studies and refined by the researchers to ensure that the extracted data were relevant to the objective and the research question [30].

3.4. Data Analysis and Reporting the Results

Data were extracted using a data extraction form and then manually analysed, summarised, and presented using conceptual content analysis to identify, quantify, and enumerate the frequencies of social dimensions in the ex-post evaluation literature. This is an approach to a methodical interpretation of the textual data content by using a coding technique to search for themes or patterns [34].

The coding process was conducted by two researchers through (1) data immersion, (2) reduction, and (3) interpretation [35]. This is a logical process that involves the researchers to first familiarise and engage with the charted article results, then divide the textual results into meaningful units for condensation, and finally, formulating codes to guide the process of developing themes [36]. For the reliability of the results, articles were ordered according to the categorised themes, however, disparities in the categorised themes between the researchers were resolved through a discussion and in the event of disagreements, a third senior researcher was consulted.

4. Results

Out of (n = 1695) studies obtained through a database search, (n = 1364) were extracted from Scopus and (n = 331) from the Web of Science. During screening, (n = 350) studies were excluded by document filters, (n = 281) were duplicates and (n = 1037) fell through by title and abstract. A total of (n = 27) studies were included for review.

4.1. Geographical Distribution of Reviewed Studies

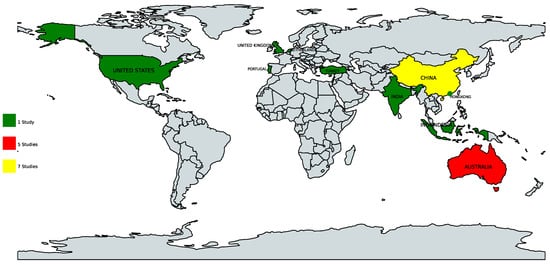

A total of (n = 27) studies conducted in PPPIP ex-post evaluation were distributed as follows (Figure 3): seven in China, five in Australia, one each in Portugal, India, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Indonesia, Turkey, and the United States of America; the remaining seven studies were not country specific.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of reviewed studies in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIP.

4.2. Time Trend of Reviewed Studies

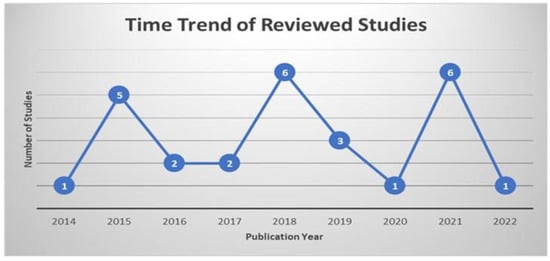

The reviewed studies spanned a period of eight years from 2014 to 2022 (Figure 4). The trend revealed a haphazard pattern with peaks and slumps in between the years.

Figure 4.

Time trend of the reviewed studies.

4.3. Distribution of Studies per Author

The review of studies on the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs (Table 2) showed that out of 27 studies, only two authors had published more than one article, thus five articles from [37,38,39,40,41] while [2,23] had two articles. The remaining 23 authors had one article each.

Table 2.

Distribution of studies per author.

4.4. Characteristics of Included Studies

A summary of the study objectives and design is provided in Table 3. A scoping review does not limit the included studies to a particular design due to the need to obtain a wide-ranging understanding of the concept [32]. Out of the (n = 27) studies, there were nine case studies, eight quantitative, four reviews, three mixed-methods, two qualitative, and one document analysis.

Table 3.

Aim and design of the included studies.

The aims of the included studies (n = 27) were distributed as follows: 10 focused on either developing an ex-post performance evaluation framework or testing an existing framework [14,18,19,20,25,37,38,39,41,47]; seven proposed, developed, or reviewed PPP performance measurement systems [2,5,16,40,46,48,50]; six conducted an ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs [9,17,27,42,45,49]; two examined or assessed the performance evaluation of PPPIPs [23,44]. Finally, (n = 1) aimed at understanding the PPP performance measurement problems and proposed improvements using BIM [24,43] and developed an ex-post impact evaluation method for PPP projects.

4.5. Type of Social Dimensions Included in PPPIP Ex-Post Evaluation

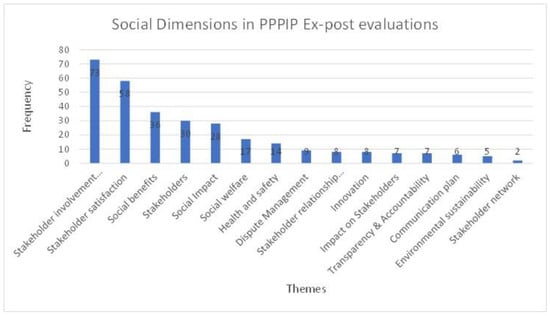

The review aimed at answering the following question: “What type of social dimensions are included in existing ex-post evaluation of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects?” The results had 15 core themes (Figure 5), with high frequencies for stakeholder involvement/engagement, stakeholder satisfaction, social benefits, stakeholders, social impact, social welfare, and health and safety.

Figure 5.

Themes and frequencies of social dimensions in PPPIP ex-post evaluation.

Lower frequencies were recorded for dispute management, stakeholder relationship management, innovation, impact on stakeholders, transparency, and accountability, communication plan, environmental sustainability, and stakeholder network. Table 4 provides a summary of the core themes per author.

Table 4.

Core themes on the social dimensions per author.

5. Discussion

The results were categorised and reported under five main themes: geographical distribution of the reviewed studies, time trend of the reviewed studies, distribution of studies per author, characteristics of the included studies, and type of social dimensions included in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs. The development of themes was guided by the approach in [34] to interpret the textual data content through a coding technique.

5.1. Geographical Distribution of Reviewed Studies

The findings indicate that research on PPPIP ex-post evaluation is low considering that there was no limitation on the period of included studies. Moreover, in settings where ex-post evaluation has been explored, few studies exist. The results echo assertions made by [47] on the paucity of the literature on the evaluation of joint venture (JV) PPPs. Although [47] focused on JVPPPs, their observations can be extended to all PPP projects and are supported by [42]. The scholars highlight a lack of comprehensive and common evaluation methodologies, which has potentially contributed to the low uptake of PPPIP ex-post evaluation as a research area.

Globally, studies focusing on aspects of the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs are spread among the continents of Asia, Australia, North America, and Europe. Asia has 11 studies (seven for China and one each for India, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and Turkey), Australia has five studies, while Europe has three studies (the United Kingdom, Portugal, and the Netherlands), and North America has one study (United States of America). However, Africa and South America did not register any studies.

Additionally, the distribution of studies according to the income of countries has revealed a surprising trend. The high-income countries of Australia, the UK, USA, Portugal, Hong Kong, and the Netherlands led with a combined total of 10 studies. Second, the upper middle-income countries of China and Turkey had a combined total of eight studies, and finally, the lower middle-income countries of Indonesia and India had a combined total of two studies. Conspicuously missing were low-income countries, which did not register any studies.

The implications of the sparse distribution of studies with regard to the global positioning and income distribution of countries are as follows: (1) There is a dearth of literature and common approaches in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs globally, agreeing with the previously mentioned studies and (2) a critical dimension is brought to light, and thus the low uptake of PPPIP ex-post evaluation as a research area in low-income countries, which is a cause for concern considering that PPPIPs are adopted to mitigate infrastructure funding deficits, hence why their ex-post evaluation is important.

Therefore, the non-existence of research in low-income countries might be due to a lack of information to support PPPIP ex-post evaluation. The challenge of the lack of information for PPPs was highlighted by [51], who bemoaned the lack of cost information in low- and middle-income countries and these assertions were concurred by [52], who highlighted the secrecy surrounding PPP deals in South Africa, making their ex-post evaluation difficult.

5.2. Time Trend of Reviewed Studies

Fluctuations were noted in the pattern of published studies, with six peaks in 2021 and 2018, and five in 2015, while slumps were noted with three in 2019, two in 2016 and 2017, while 2020 and 2014 had one each. The time of the present study was the first half of 2022, and only one study was in press, unlike in the first half of 2021, which had five published studies. Despite the first half of 2022 having one study in press, the time trend of the reviewed studies presented a mix of a haphazard and an incremental style of publication.

Overall, the trend confirms the paucity of studies in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs and affirms the need for more research to enable future systematic reviews to be undertaken in this area.

5.3. Distribution of Studies per Author

The scholarship of ex-post evaluation in PPPIPs in the 27 included studies was distributed among 25 authors. The author of [37,38,39,40,41] was the most published author with five articles followed by [2,23] with two articles. The remaining 23 authors had one article each. All in all, the results show an under exploitation in the research of ex-post evaluation in PPP infrastructure projects.

5.4. Characteristics of Included Studies

The results show that case studies, quantitative, reviews, and mixed methods were the most used study designs. It appears that the objectives of the studies motivated the choice of an appropriate study design, where the focus was on developing an ex-post performance evaluation framework or testing an existing framework, proposing, developing, or reviewing PPP performance measurement systems, conducting an ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs, examining or assessing the performance evaluation of PPPIPs, aimed at understanding the PPP performance measurement problems and proposed improvements through the use of BIM and developing an ex-post impact evaluation method for PPP projects.

Case studies dominated the type of research design used in the included studies due to the nature of PPPIPs and their ex-post evaluations, where archival analysis of existing data is paramount to assessing the performance of the PPP projects (Table 3). Quantitative study design ranked second and was prevalent in studies that focused on developing ex-post performance evaluation frameworks, testing an existing framework, evaluating the socio-economic impacts of PPPs, or establishing a performance measurement system. This can be attributed to the economic nature of PPPIPs, which falls under the umbrella of economic theory where project performance has quantitative aspects for measurement.

Reviews ranked third and focused on the conceptualisation of performance measurement frameworks for PPPIPs and the use of cutting-edge technologies such as BIM to enhance the PPPIPs’ performance measurement. Reviews can identify gaps in the extant literature and provide direction on addressing these gaps. For example, ref. [40] assessed the effectiveness of current ex-post evaluations and their direction on efficient and robust performance measurement of PPP infrastructure projects. Ref. [37] reviewed the literature on PPP and construction project evaluation and proposed a dynamic life cycle performance measurement framework for PPP infrastructure projects. The ability of reviews to identify gaps in the literature and provide ways of addressing those gaps was underscored in these studies.

The number of mixed methods was low though it ranked fourth, however, these types of studies can capture multi-dimensional aspects of a subject and are better suited in evaluation of PPP infrastructure projects.

Qualitative studies ranked very low, which was surprising considering that PPPIP ex-post evaluation needs to encompass the social impacts affecting stakeholders. The lack of qualitative studies poses questions such as: How are social impacts evaluated if the communities are not engaged for their honest views? The findings on qualitative studies corresponded to [4], who bemoaned the neglect of social dimensions in the literature and practice, thereby imposing a negative impact on the social sustainability of PPP projects. Related concerns were raised by [21] through advocacy for the inclusion of communities in construction project planning and design for a better understanding of their socio-cultural spaces.

5.5. Identified Social Dimensions in PPPIP Ex-Post Evaluation

5.5.1. Stakeholder Involvement/Engagement

This theme had the highest frequency of 73 and was included by all 25 authors (Figure 5 and Table 4), which shows its paramount importance for inclusion in PPPIP ex-post evaluations. The interrelations among the mapped social dimensions were noted and discussed. First, there is a need to assess whether there were consultations with the public and stakeholders prior to the implementation of the project [41,44] to solicit their input, expectations, interests, and concerns [2,14,17,20,23,24,38,41,46,50] as well as their views and opinions [5,20,40,41]. The outlined social aspects allow for coordination and produce synergies [19,47], which are central in PPPIPs and their subsequent ex-post evaluation.

Second, there is the consideration of factors that focus on the needs and requirements of stakeholders [2,5,16,18,23,37,38,43,46] and their indicators [37,41], and to check whether they were included and aligned to the objectives of the project. Additionally, stakeholders have responsibilities [37,41,43] as beneficiaries, as such, they must be knowledgeable on the benefits of the project [45]. The concept of informing the locals of the benefits of the project is espoused in stakeholder theory where stakeholders are regarded not only as beneficiaries, but also as a group that can impact the project [6], hence their engagement is crucial to achieve the social sustainability of PPP infrastructure projects.

Finally, there was a focus on the multifaceted social dimensions that led to the concept of willingness to support the project, and subsequently use the built facility. The motivation of the general public to support the project [14,19,23,25,27,42,46,47] and the willingness of the end-users to use the asset for a long period [25,38,41] is influenced by their perceptions and opinions of the overall performance and service quality of the asset [5,14,18]. Furthermore, there must be social considerations [5] and an intention to address the concerns of the end-users [14,20]. The social dimensions highlighted are critical since they border on the long-term affordability and quality of the facility.

Additionally, issues of affordability in PPPIPs were raised by [53] due to the need for a user fee to be paid by the community to access a facility. This has a direct social impact on people, first in circumstances where the fee is high, and users cannot afford to pay for access, and second, if the quality of the service provided falls below their expectation.

Overall, stakeholder involvement is considered as the driving force in PPPIPs, hence evaluating the multi-faceted social dimensions impacting stakeholders is crucial for the social sustainability of PPP infrastructure projects. The idea of the social sustainability of PPPIPs is supported by [3] through the TBL concept and [5] by advocating for the evaluation of social impacts to safeguard the interests of the stakeholders.

5.5.2. Stakeholder Satisfaction

Ranked second in importance, stakeholder satisfaction was included by 21 out of 25 authors. The relationship between stakeholder satisfaction and the previous theme of stakeholder engagement is symbiotic, as satisfied stakeholders emerge from their initial engagement in PPP infrastructure projects. Amongst the key issues addressed was end-user satisfaction [2,16,24,37,38,39,41,42,50]; stakeholder satisfaction [2,5,17,19,37,38,39,41,43,46,48]; public satisfaction [17,18,43,47,48,50], public client satisfaction [16,25,37,39,42], and skilled employee satisfaction [39]. Although the outlined stakeholders are diverse, they share a common goal, which is their quest for satisfaction. However, it is significant to consider them as a diverse group during ex-post evaluation since they are differently impacted, or they might affect the project in various ways.

In addition, the results singled out community desired parameters [14], which also affects the satisfaction of communities. Furthermore, the focus should be on the acceptability level of users for the regime [44], user fee issues [24], public discontent [47] and project service quality [50], benefits to the public sector [5] and society [25], and the attitude and behaviour of the public towards the service [18]. The social aspects outlined borders on affordability and the motivation of the general public to utilise the facility, and moreover reinforces the existing interdependencies between stakeholder satisfaction and engagement.

Stakeholders in PPP projects are underpinned by stakeholder theory and can benefit from the project, impact, or be impacted by the project [6]. Moreover, stakeholders are an integral social dimension in PPPIP ex-post evaluation [5] considering the ranking and issues that have been mapped from the literature in the present review. However, there is a notable gap between the stakeholder frequency of 58 and stakeholder involvement, which ranked first with a frequency of 73, which signifies the low attention this theme has been afforded in literature. The existing disparity might be due to the rent seeking theory in PPPIPs [53], which use people to achieve the goals of the public sector while neglecting their interests [54].

5.5.3. Social Benefits

Social benefits ranked third with a frequency of 38 and was included by 17 out of 25 authors. The further decline in ranking of dimensions that are core to the social sustainability of PPP projects is worrying. The aspects considered were social benefits to either the community in general, local society or end-users [2,5,23,27,37,39,41,44,50]; social costs evaluation [14,42]; suitability of user fees [5,42], and public benefits [17,48]. The outlined social benefits were linked to affordability and further demonstrated the mutuality that exists with the previous themes of stakeholder engagement and stakeholder satisfaction.

Additional aspects were social capital [19,39,48], road safety [44,45], social-economic factors and service performance [37,41], social value, taxation, and benefits to local industries and communities [41], social good, future development to the society, moral benefits and social sustainability of PPP projects [5], security [19], and land acquisition [45]. A link between the highlighted social dimensions and project externalities was established due to the inclusion of aspects that have an impact on society and the economy [20]. Moreover, project externality is used not only for general ex-post evaluation, but to evaluate the regional social sustainability contribution of PPP infrastructure projects [22].

A point of concern of the inclusion of social sustainability as a dimension was mentioned by only one author [5] out of 17. Social sustainability was among the three dimensions of the TBL concept in the sustainable development of projects [3], which is the underpinning basis of PPP projects.

5.5.4. Stakeholders

Although stakeholders are project beneficiaries and may exert a positive or negative influence on the project [6], only 12 out of the 25 authors considered stakeholders as a social dimension (Table 5). Stakeholders in PPPIP ex-post evaluations are responsible for the social sustainability of the project, as such, their interests are of paramount importance and should not be neglected [5]

Table 5.

Stakeholders.

The multiplicity that exists with stakeholders in PPPIPs is presented in Table 5. They are separated largely due to dynamics affecting their interests and needs [6], hence, they should be considered as such in an ex-post evaluation. For example, a difference in needs might prevail between the general public and the community surrounding the infrastructure because of their proximity to the asset. If issues of noise and dust pollution emerge, then those stakeholders close to the facility are likely to be impacted more than the general public.

Similarly, the impact of the project to government and other stakeholders such as consumers and pressure groups might differ. More importantly, specificity is critical when assessing social impacts because there is diversity in the way that stakeholders are affected.

5.5.5. Social Impact

Social impact had a frequency of 28 and was discussed by 12 out of 25 authors. Although authors agreed on some of the aspects such as social impacts of the asset whether long-term or not, intended or unintended to the local community and the public [2,16,23,24,25,38,42], diversity was noted in aspects included by the following authors: ref. [24] looked at beneficiary assessment on their experiences and observation, beneficiary and social evaluation capacity of the users, participatory evaluation using qualitative data from users, beneficiaries and community; ref. [41] looked at the resilience score; ref. [43], social influence; and [5] addressed corporate social responsibility.

Additional social impacts included social responsibility with no specificity as to whether it was for the corporates to the community or the community to the project; refs. [2,19] considered the contribution of the PPP project to the local community while [47] highlighted the democratic principles and transformation, especially the conduct of the public sector, and cultural differences between the government and the private partner. The issue of culture shock requires adequate attention because it can affect the success of a project. This was evidenced by [47], who outlined how strained relationships resulting from culture shocks led to low utilisation of a JVPPP asset by the users in Hong Kong.

Generally, the issues raised in this theme point to indicators considered in a social impact assessment. The parallels were notable in the ten principles for social impact assessment prepared by [55], and they reinforced the centrality of social impact as an important dimension in PPPIP ex-post evaluation.

5.5.6. Social Welfare

Social welfare was included by nine out of 25 authors. Mapped out issues were social welfare analysis linked to allocative efficiency [14], which deals with user fees and their perspective on the performance and quality of the service [5,14,18]. This aspect has been documented as affordability [53] and is critical in PPPIP ex-post evaluation.

In addition, the overall theme presented an interdependence with stakeholder satisfaction due to the significant link between the welfare of the stakeholders and their satisfaction. Moreover, the outlined aspects were the welfare of the public [50]; social welfare impacts [9]; social welfare and changes in social contexts [44]; culturally related aspects [27]; psychological and physiological needs [18]; preparing for the future through a change in lifestyle; and the quality and quantity of the asset and service, which contribute to welfare [5].

Furthermore, ref. [45] focused on direct and timely compensation to landowners to avoid public hostilities and the resettlement and rehabilitation of displaced families, while [37] considered accidents during construction, proactive and reactive maintenance with minimal delays, and disruptions of service during operation and use.

Overall, there was diversity in the issues raised by the authors, and this might be attributed to stakeholder dynamics in PPPIPs and the multi-faceted issues affecting them [6]. Regardless of the variations, social welfare is an important dimension in the achievement of social sustainability of PPP infrastructure projects.

5.5.7. Health and Safety

Ranked in seventh position with a frequency of 14, health and safety was included by nine out of 25 authors. Its importance to PPPIPs cannot be over emphasised as accidents affect the lives of the workers and the community and impact the success of the project. Additionally, ref. [56] indicated that health and safety was a critical success factor for operational PPP infrastructure projects, which underpins its necessity as a social dimension.

Breaking down the theme, it addressed issues such as health and safety on a general level [17,37,40,41,50]; safety records [17]; public safety [18]; and worksite safety management [45,48,50]. However, occupational health and safety were highlighted by [39], while the other authors did not. Generally, the separation of health and safety requirements according to different stakeholder groups was observed, and this notion is exclusive to the diversity existing in PPPIPs due to multiple stakeholder settings. As such, ex-post evaluation must also respect such dynamics.

5.5.8. Dispute Management

Although considered by six out of 25 authors, the management of disputes is paramount to the success of the PPPIPs and social sustainability as it can be characterised by protracted legal battles that can impact progress. It is puzzling that disputes and their management were not regarded as an important social aspect in the present review. Their little regard can be seen in their inclusion by only a few authors, and the considered aspects were the minimisation of disputes [37,41] and dispute and conflict resolution [16,17,40,41,47].

Despite their minimal consideration, ref. [57] indicates that disputes are a huge challenge for PPPs and require effective management to mitigate their impact.

5.5.9. Stakeholder Relationship Management

A mutuality exists between this dimension and dispute management due to the necessity for healthy relationships in a multi-stakeholder project environment like PPPIPs to minimise tensions that can lead to disputes and derail the objectives of the project. This theme focused on the relationship between the concessionaire, subcontractors, and suppliers [25,43]; cordial relationships amongst all the stakeholders involved [14,42,46]; and the relationship between the government, the private partner, and end-users [5,47].

However, this important dimension was only considered by seven out of 25 authors. Additionally, the differentiation of the stakeholders in the findings might be attributed to the diversity in relationships that exist in PPPIPs, as indicated in previous dimensions. For example, the relationship between government and the private sector and government and end-users, or the private sector and end-users will differ. Hence, stakeholder relationship management must be regarded as such in an ex-post evaluation.

5.5.10. Innovation

This was broken down into: innovation and learning [25,37,48]; innovation in products, processes, and systems [14,41]; obtaining inputs for innovation from stakeholders—crowd sourcing [41]; and innovation and asset sustainability [38].

While [41] focused on crowd sourcing, ref. [47] considered connectivity with an intention of stimulation for innovation. These two aspects are similar as they both focus on obtaining innovative inputs from stakeholders. Apart from [14], who specified the type of innovation as the provision of childcare centres in the PPPIP ex-post evaluation they conducted, the other authors were silent on the exact type of innovations.

Despite the silence, innovation is central to PPPIPs, and is heralded as a tool that can enhance the initiation, procurement, implementation, and operation of built assets. These processes fall under the aspects highlighted by [14,41]. Moreover, innovative processes in PPPIPs are evidenced by the adoption of BIM in Australia to “future proof” their public infrastructure assets [16].

5.5.11. Impact on Stakeholders

The discussion on this theme appeared harmonised as the focus was the impact on either the main and specific stakeholders [24,44] or the long-term impacts of the asset on the taxpayers, the public, or local communities. In [38], the authors focused on the contribution of the asset to local communities.

Finally, the discussions centred on equity [50] without any specific stipulations, unlike in [19], where they considered the impact of the project on the participants and equity in the context of society, social, and cultural fairness.

This theme was included by five out of 25 authors; however, it is the central aspect of stakeholder theory that anchors the present review. The theoretical foundations support the need for an intentional positive impact to stakeholders [7]. Additionally, this concept was reinforced by [4], who contends that construction projects, PPPIP inclusive, are social vehicles and as such, they should impact communities in a positive way.

5.5.12. Transparency and Accountability

Although this is critical for PPP projects, this theme was not considered by most authors, and was included by five out of 25 authors. Issues addressed were transparency [14,47]; government, politics, and accountability [24]; public sector and democratic accountability, secrecy, and community engagement [47]; government reputation [5] and governance [40]. Although transparency and accountability appeared to be insignificant in the PPPIP ex-post evaluation literature, this theme acts as a springboard for best practice [10,42], hence requires serious attention.

Generally, challenges on transparency and accountability were lamented in the literature by [52], who documented secrecy, transparency, and accountability as gaps with South African PPPs, hence concurring with [5,14,24,47] in the present review. Similarly, restrictive information dissemination on PPPs, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, was noted by [51], who cited a lack of cost information in PPP projects. The issues raised in this dimension were interrelated to those that emerged from the geographical positioning of studies on PPPIP ex-post evaluation in the review.

5.5.13. Communication Plan

This dimension shares a mutual relationship with other themes such as stakeholder relationship management, and by extension, dispute management. The former calls for healthy relationships amongst all stakeholders in a PPPIP [14,42,46], while for the latter, communication is its lifeblood, among other factors to minimise disputes [37,41].

The aforementioned aspects are embedded in the need for a communication plan that includes the stakeholders’ requirements and communication [37,41,43]; a communication plan in the operation phase to address the changing needs of stakeholders [14]; a channel for public complaints [18], and the misconception of PPPs as a donation [24]. The issue of a lack of understanding of what PPIPs entail must be given serious attention since it can impact on the objectives of the project. To mitigate such misconceptions, the stakeholder engagement theme suggested educating local communities on the benefits of the project [45].

Despite being discussed by six out of 25 authors, communication remains the life blood of any project and its inclusion in PPPIP ex-post evaluation can lead to project success and the achievement of social sustainability.

5.5.14. Environmental Sustainability

This theme scored miserably after being discussed by three out of 25 authors and focused on the environment and environmental friendliness [37]; long-term environmental sustainability [14]; and community greening [19]. Despite commanding little attention as a social dimension in PPPIP ex-post evaluation literature, it has a symbiotic relationship with the social welfare theme, particularly the welfare of the public [50] and the psychological and physiological needs [18]. Additionally, it underscores the concept of the interdependence of all three dimensions for a wholistic achievement of sustainable development [3], hence the need to especially include those aspects that speak to social sustainability. Although the focus is environmental sustainability, it has a direct social impact on communities in which PPPIPs are implemented. For example, the environment, environmental friendliness, and community greening can be linked to the welfare of the public and their psychological and physiological needs.

5.5.15. Stakeholder Network

This theme was included by two out of 25 authors [38,41]. Although included in the review, this appears to be a silent theme as there were no specific issues addressed. However, the neglect of this theme is worrying, as it plays a crucial role in providing satisfaction to the stakeholders through their engagement and communication [58]. Additionally, its mutuality to other themes in the review such as stakeholder engagement, satisfaction, stakeholder relationship management, and communication plan was established, hence the need for its consideration in PPPIP ex-post evaluation.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review mapped out the evidence on the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs and the type of social dimensions included by scholars. Additionally, it revealed and established mutual relationships existing among the theoretical foundation of the review, the themes, and identified social dimensions. Additionally, diversity was seen in the needs and interests of the stakeholders, and finally, the low research output in the ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs was observed.

The review adopted a stakeholder approach for guidance. Notably, affordability was highlighted by the authors, which is an underpinning concept in stakeholder theory and was found in themes of stakeholder engagement, social benefits, and social welfare. Additionally, stakeholder theory is intrinsic in other themes considered in the review.

Moreover, mutual relationships were established between the geographical distribution of studies and transparency and accountability because of the secrecy in PPP projects commissioned in low- and middle-income countries. Further links were seen between stakeholder satisfaction and stakeholder engagement; social benefits to stakeholder satisfaction, and stakeholder engagement; social welfare to environmental sustainability and stakeholder satisfaction. In addition, connections were noted between stakeholder relationship management and dispute management; communication plan to stakeholder relationship management, dispute management, stakeholder engagement, and stakeholder satisfaction; environmental sustainability and social welfare. Finally, the stakeholder network was connected to stakeholder engagement, stakeholder satisfaction, communication plan, and stakeholder relationship management.

Furthermore, diversity was seen in themes of the stakeholders, social welfare, health and safety, and stakeholder relationship management. The diversity was attributed to two key aspects of PPPIPs and their ex-post evaluation. First is the multiple stakeholder setting in which they are implemented, and second are the different interests and needs of the various stakeholders. Due to the prevailing circumstances, ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs must consider the multiplicity that exists with the identified social dimensions.

Some of the identified social dimensions were mutually connected, however, a lack of consistency on the included dimensions in the reviewed PPPIP ex-post evaluation frameworks or factors was observed. The haphazard pattern has made assessing the contribution of social dimensions in the evaluation of social impacts of PPPIPs difficult. Therefore, a decision was made that due to the heterogenous nature of the results, they should be taken as descriptive and inconclusive since they present a variety of evidence on the topic.

Presently, research on ex-post evaluation of PPPIPs is low, present in a few countries, and exclusive to a few authors (n = 23), as evidenced by the sparse distribution of studies across the globe. Regardless of the absence of limitations imposed on the period of the included studies, the review yielded few studies in the four continents of Asia (n = 11), Australia (n = 5), Europe (n = 3), and North America (n = 1). The remaining seven studies were not specific to any country; however, Africa and South America had no studies. A huge research potential has been revealed with specific focus on the social dimension of the triple bottom line concept of sustainable development to achieve the social sustainability of PPPIPs. Therefore, further research is required in this area to improve the number of studies that can be used for future systematic reviews.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.N.S., I.M, M.S.R. and S.L.Z.; Methodology, G.N.S., I.M., M.S.R. and S.L.Z.; Investigation, G.N.S. and I.M.; Validation, M.S.R. and S.L.Z.; Formal analysis, G.N.S. and I.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, G.N.S.; Writing—review and editing, I.M., M.S.R. and S.L.Z.; Project administration, I.M., M.S.R. and S.L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intra-Africa Mobility Scheme of the European Union in partnership with the African Union in the framework of the project 624204-PANAF-1-2020-1-ZA-PANAF-MOBAF under the Africa Sustainable Infrastructure Mobility (ASIM) scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The opinions and conclusions in this research are exclusive to the authors and cannot be attributed to ASIM. The review is part of collaborative research at the Centre of Applied Research and Innovation in the Built Environment (CARINBE).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, W. A review of emerging trends in global PPP research: Analysis and visualization. Scientometrics 2016, 107, 1111–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.J.; Love, P.E.D.; Smith, J.; Irani, Z.; Hajli, N.; Sing, M.C.P. From design to operations: A process management life-cycle performance measurement system for Public-Private Partnerships. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doloi, H. Assessing stakeholders’ influence on social performance of infrastructure projects. Facilities 2012, 30, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M. Social procurement in UK construction projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, H. Sustainable performance measurements for public-private partnership projects: Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn, J.; Wojewnik-Filipkowska, A. Stakeholder Analysis and Their Attitude towards PPP Success. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.R. SRATEGIC MANAGEMENT: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing Inc.: Montclair, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani, O.M.; Geddes, R.R.; Gao, H.O.; Bel, G. Social welfare analysis of investment public-private partnership approaches for transportation projects. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 88, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Daito, N.; Gifford, J.L. Socioeconomic impacts of transportation public-private partnerships: A dynamic CGE assessment. Transp. Policy 2017, 58, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, G.; Vignetti, S.; Pancotti, C. Ex-post evaluation of major infrastructure projects. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 42, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellowell, M.; Vecchi, V. An Evaluation of the Projected Returns to Investors on 10 PFI Projects Commissioned by the National Health Service. Financ. Account. Manag. 2012, 28, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, D.; Pollock, A.M.; Price, D.; Shaoul, J. The private finance initiative: PFI in the NHS—Is there an economic case? BMJ 1999, 319, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, G. Developments in the public-private partnership funding of Scottish schools. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2008, 9, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.M.; Duffield, C.; Hui, F.K.P. An enhanced framework for assessing the operational performance of public-private partnership school projects. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018, 8, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.J.; Love, P.E.D.; Sing, M.C.P.; Smith, J. Ex Post Evaluation of Economic Infrastructure Assets: Significance of Regional Heterogeneities in Australia. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2019, 25, 05019005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.D.; Liu, J.X.; Matthews, J.; Sing, C.P.; Smith, J. Future proofing PPPs: Life-cycle performance measurement and Building Information Modelling. Autom. Constr. 2015, 56, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Martek, I.; Chen, C.; Chan, A.P.C.; Yu, Y. Lifecycle performance measurement of public-private partnerships: A case study in China’s water sector. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2018, 22, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Lv, L. Public satisfaction evaluation of urban water environment treatment public-private partnership project: A case study from China. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 39, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Ma, L. Performance evaluation of public-private partnership projects from the perspective of Efficiency, Economic, Effectiveness, and Equity: A study of residential renovation projects in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Martek, I.; Chen, C.; Tian, J. A phase-oriented evaluation framework for China’s PPP projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanda, J.O. Developing a social sustainability assessment framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.F.; Zhang, L.; Tan, Y.T.; Skibniewski, M.J. Evaluating the regional social sustainability contribution of public-private partnerships in China: The development of an indicator system. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.J.; Love, P.E.D.; Smith, J.; Sing, M.C.P.; Matthews, J. Evaluation of public private partnerships: A life-cycle Performance Prism for ensuring value for money. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2018, 36, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros-Romero, J.; Aibinu, A.A. Ex post impact evaluation of PPP projects: An exploratory research. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2019, 9, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okudan, O.; Budayan, C.; Dikmen, I. Development of a conceptual life cycle performance measurement system for build-operate-transfer (BOT) projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 1635–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ex-Post Assessment of PPPs and How to Better Demonstrate Outcomes; EPEC: Paris, France, 2018.

- Shu, X.; Smyth, S.; Haslam, J. Post-decision project evaluation of UK public–private partnerships: Insights from planning practice. Public Money Manag. 2021, 41, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Dos Santos, K.B.; Pap, R. Practical Guidance for Knowledge Synthesis: Scoping Review Methods. Asian Nurs. Res. Korean Soc. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 13, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, J.; Damschroder, L. Qualitative Content Analysis. In Empirical Methods for Bioethics: A Primer; Jacoby, L., Siminoff, L.A., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: West Yorkshire, UK, 2007; Volume 11, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Love, P.E.D.; Davis, P.R.; Smith, J.; Regan, M. Conceptual framework for the performance measurement of public-private partnerships. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2015, 21, 04014023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Love, P.E.D.; Smith, J.; Matthews, J.; Sing, C.P. Praxis of Performance Measurement in Public-Private Partnerships: Moving beyond the Iron Triangle. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04016004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Love, P.E.D.; Sing, M.C.P.; Smith, J.; Matthews, J. PPP social infrastructure procurement: Examining the feasibility of a lifecycle performance measurement framework. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2017, 23, 04016041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Love, P.E.D.; Smith, J.; Regan, M.; Sutrisna, M. Public-Private Partnerships: A review of theory and practice of performance measurement. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2014, 63, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Love, P.E.D.; Smith, J.; Regan, M.; Palaneeswaran, E. Review of performance measurement: Implications for public–private partnerships. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2015, 5, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-S.; Leatemia, G.T. Critical process and factors for ex-post evaluation of public-private partnership infrastructure projects in Indonesia. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 05016011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, X.; Ke, Y.; Xu, W.; Xu, Z.; Skibniewski, M. Developing a building information modeling–based performance management system for public–private partnerships. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 1727–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Cruz, C.O.; Moura, F. Ex post evaluation of PPP government-led renegotiations: Impacts on the financing of road infrastructure. Eng. Econ. 2019, 64, 116–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalkrishna, N.; Karnam, G. Performance Analysis of National Highways Public Private Partnerships in India. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2015, 20, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Thuc, L.D. Life Cycle Performance Measurement in Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2021, 27, 06021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.D.; Huque, A.S. Public Money and Mickey Mouse: Evaluating performance and accountability in the Hong Kong Disneyland joint venture public–private partnership. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yang, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhong, M. Research on performance evaluation system of shale gas PPP project based on matter element analysis. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 4657383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.; Klijn, E.H.; Verweij, S.; Duijn, M.; van Meerkerk, I.; Metselaar, S.; Warsen, R. The Performance of Public–Private Partnerships: An Evaluation of 15 Years DBFM in Dutch Infrastructure Governance. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2022, 45, 998–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Yue, Y.; Xiahou, X.; Tang, S.; Li, Q. Research on performance measurement and simulation of civil air defense PPP projects using system dynamics. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2021, 27, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, J.S.; Azami-aghdash, S.; Gharaee, H. Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 215013272094376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombad, M.C. Enhancing accountability in public-private partnerships in South Africa. S. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2015, 18, 66–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostepaniuk, A. The Development of the Public-Private Partnership Concept in Economic Theory. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2016, 6, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ness, K. The discourse of ‘Respect for People’ in UK construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvam, R.; Baringo, D.; Martinez, J. Social Impact Assessment: Integrating Social Issues in Development Projects; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C.; Ameyaw, E.E. A fuzzy synthetic evaluation analysis of operational management critical success factors for public-private partnership infrastructure projects. Benchmarking Int. J. 2017, 24, 2092–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okudan, O.; Çevikbaş, M. Alternative Dispute Resolution Selection Framework to Settle Disputes in Public–Private Partnership Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkul, M.; Yitmen, I.; Celik, T. Dynamics of stakeholder engagement in mega transport infrastructure projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 13, 1465–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).