Home Literacy Environment and Chinese-Canadian First Graders’ Bilingual Vocabulary Profiles: A Mixed Methods Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Children’s Bilingual Development Patterns in the North American Context

1.2. Home Language Environment and Bilingual Development

- What are the patterns of achievement in bilingual oral receptive vocabulary among Chinese-English first graders?

- What are the underlying profiles of the children’s Chinese-English bilingual vocabulary achievement?

- What are the home-related factors that account for the children’s variations in their bilingual English and Chinese receptive vocabulary?

2. Methods

2.1. Phrase I Cluster Analysis

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Receptive Vocabulary Knowledge Measures

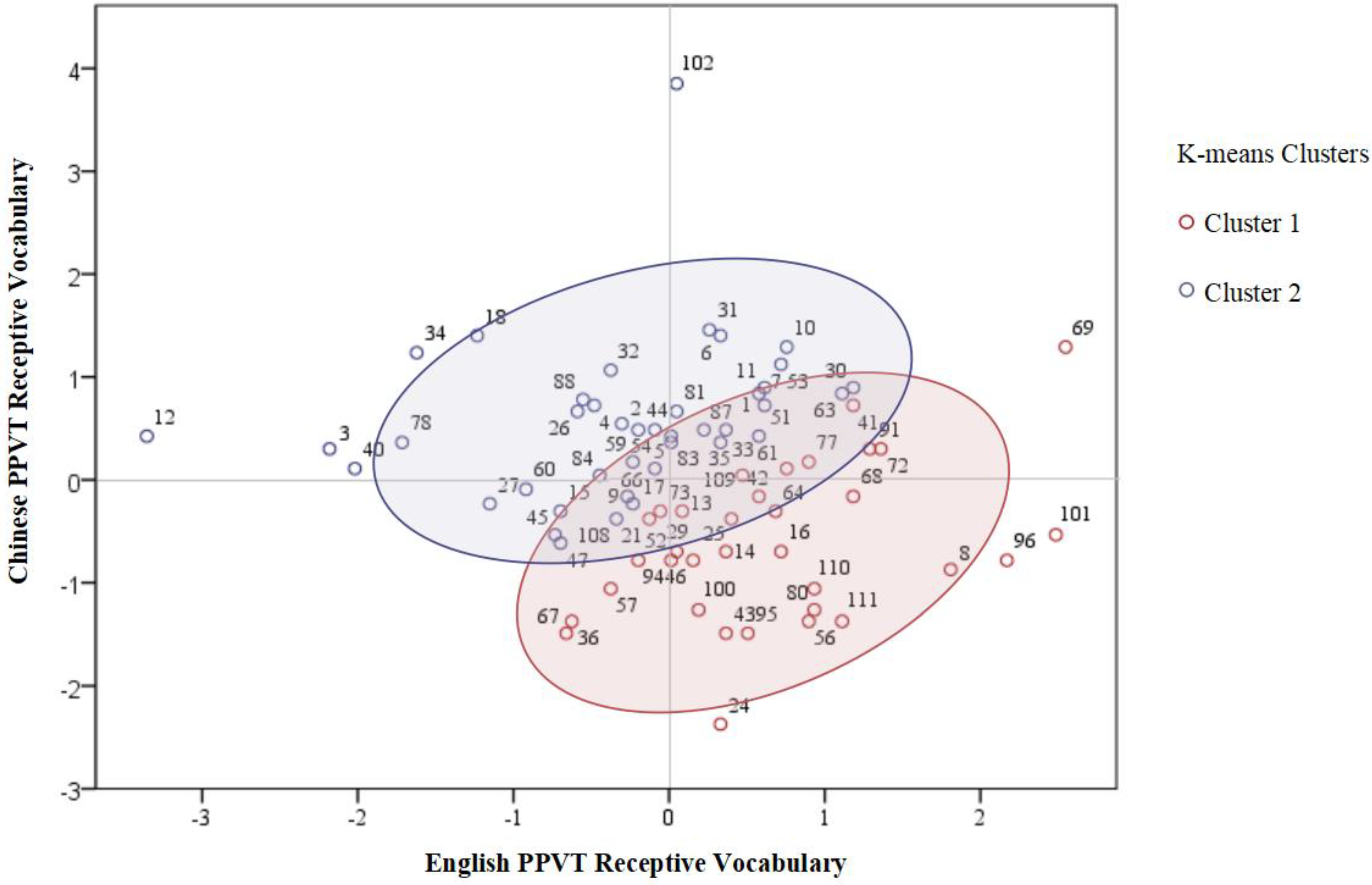

2.1.3. Cluster Analysis

2.2. Phase II Qualitative Analysis

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Home Literacy Environment Measures

2.2.3. Thematic Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. Chinese-Canadian Children’s Profiles in Bilingual Vocabulary Development

3.2. Home Factors That Contributed to the Divergent Profiles

Chinese is not that important to him, because his English is really good, and he does not need that [Chinese language ability] to find a job. I am not saying he does not need Chinese, but he probably will find a job by just taking advantage of his native-like English proficiency.(Child A101, EN−5/CN−2)

First of all, as they are Chinese descendants, I think it is necessary for them to learn the Chinese language. And if they would like to travel back to China, they cannot communicate with their grandpa, grandma, and other relatives or friends in English, right? And my English is not that good, and if I communicate with them in English, I might not be able to understand them perfectly. So, I ask them to speak Chinese only at home. Furthermore, as I usually do story-telling with them in Chinese, she [the daughter] acquired Chinese naturally, and she is willing to learn Chinese, so I took her to learn. I think there is nothing bad about learning Chinese.(Child A102, EN−2/CN−4)

When she talks to me in English, I never say she can’t speak English. I would just not respond when she talks with me in English, and she is fully aware of that and she is used to it.(Child A102, EN−2/CN−4)

Because he did not lose his Chinese, he speaks Chinese to us after he comes back home from school every day. Once home, he continues to speak Chinese but during that time, his Chinese has not changed much. He can speak Chinese very well, and it was puzzling to me as there was no Chinese-learning environment in this country. It is strange that he could speak many new Chinese words. He probably picked up those words by listening to us adults speaking them.(Child A012, EN−1/CN−3)

I just told him [the older brother] that my English is not good, so he just speaks Chinese at home. And the stories I told him, TV shows, books I bought for them are all in Chinese. Like I said, I do not know how to pick English [books], basically he just did for himself, and I would pick Chinese books for him. And the story-telling is also, if I want to tell a good story, I tell them Chinese stories.(Child A102, EN−2/CN−)

Because the three of them would talk to each other in English, so basically, among them three it is definitely English. When they speak to me, they are doing so well [in language choice] as they all basically like to use English. Then I usually reply in Chinese. This is a challenge we are facing at the moment.(Child A101, EN−5/CN−2)

Actually, I think if parents have time and energy, we should help kids learn to read and write in Chinese as well. But there are many practical issues, like the lack of time, or our energy, and the lack of cooperation from kids. Therefore, if you cannot help kids learn reading and writing [in Chinese], then you can only help them learn to listen and speak [in Chinese]. Many families make the compromise, including ours(Child A101, EN−5/CN−2)

We read almost every day. On the stairs from the first floor in our house, there are all books placed there. When she walks up the stairs, she would flip the books. When she gets bored, she would go and read. When there is only one kid at home and she has no playmates, she would feel bored. She has nothing else to do when she comes back from school. During the weekend, she would ask to play on my cellphone, but if I refuse to give her, she would just play with her dog and then sit downstairs and read books.(Child A024, EN−3/CN−1)

I have to be very honest. There is no companion or supervision on my son’s studying. This kid needs someone to accompany him, but I have no time for that. I am too busy minding my own things. He spends most of his time playing on his tablet. Or sometimes I gave him two tablets and he would just play games on his tablets, from day to night, as I have no spare time to read books with him.(ChildA012, EN−1/CN−3)

I did [encourage them to speak Chinese], but it was not very effective, because the elder bother became proficient in English very quickly, and basically became very stubborn [in speaking English]. Because of that, he had the influence on his younger brother [to speak English at home]. So, we never find a good solution on that.(Child A101, EN−5/CN−2)

As [my daughter] has an older brother, and she was born when her older brother was five years old. And when the older brother went to kindergarten, I just told him, I did not force him it would be better if you talk in Chinese at home, because Mom’s English is not good. Then he has been talking in Chinese ever since, so she is used to speaking Chinese at home.(Child A102, EN−2/CN−4)

4. Discussion

5. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietrich, S.; Hernandez, E. Language Use in The United States: 2019; American Community Survey Reports; U.S. Census Bureau: Suitland, Maryland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, L.; Lu, Y.; Kan, P.F. Lexical development in Mandarin–English bilingual children. Bilingualism 2011, 14, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Census of Population. 2022. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/mwtjn8f4 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Alba, R.; Logan, J.; Lutz, A.; Stults, B. Only English by the third generation? loss and preservation of the mother tongue among the grandchildren of contemporary immigrants. Demography 2002, 39, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosjean, F. Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, R.; Pace, A.; Levine, D.; Iglesias, A.; de Villiers, J.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Wilson, M.S.; Hirsh-Pasek, K. Home literacy environment and existing knowledge mediate the link between socioeconomic status and language learning skills in dual language learners. Early Child. Res. Q. 2021, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marif, D. Losing One’s Mother Tongue in Multicultural Canada; New Canadian Media: 2022. Available online: https://shorturl.at/dotuZ (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Li, G. Biliteracy and trilingual practices in the home context: Case studies of Chinese-Canadian children. J. Early Child. Lit. 2006, 6, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, L. Involuntary Language Loss among Immigrants: Asian-American Linguistic Autobiographies. ERIC Digest 1999. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED436982.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Li, G.; Sun, Z. Asian immigrant family school relationships and literacy learning: Patterns and explanations. In The Wiley Handbook of Family, School, and Community Relationships in Education; Sheldon, S., Turner-Vorbeck, T., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Hao, L. E pluribus unum: Bilingualism and loss of language in the second generation. Sociol. Educ. 1998, 71, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gunderson, L.; Sun, Z.; Lin, Z. Early Chinese heritage language learning in Canada: A study of Mandarin-and Cantonese-speaking children’s receptive vocabulary attainment. System 2021, 103, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2000; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J.; Swain, M. Bilingualism in Education: Aspects of Theory, Research and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxfordshire, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore, L.W. Loss of family languages: Should educators be concerned? Theory Pract. 2000, 39, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.R.; Hecht, S.A.; Lonigan, C.J. Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one-year longitudinal study. Read. Res. Q. 2002, 37, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, E.A.; Morrison, F.J. The unique contribution of home literacy environment to differences in early literacy skills. Early Child Dev. Care 1997, 127, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, C.S.; Davison, M.D.; Lawrence, F.R.; Miccio, A.W. The effect of maternal language on bilingual children’s vocabulary and emergent literacy development during Head Start and kindergarten. Sci. Stud. Read. 2009, 13, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, A.C.; Whitehurst, G.J.; Angell, A.L. The role of home literacy environment in the development of language ability in preschool children from low-income families. Early Child. Res. Q. 1994, 9, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M.; LeFevre, J.A. Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 2002, 73, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M.; LeFevre, J.A. Continuity and change in the home literacy environment as predictors of growth in vocabulary and reading. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannon, B.A.M. The contributions of informal home literacy activities to specific higher-level comprehension processes. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2018, 6, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X.L. Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Lang. Policy 2009, 8, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.A.; Fogle, L.W. Family language policy and bilingual parenting. Lang. Teach. 2013, 46, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeliovich, S. Family language policy: A case study of a Russian-Hebrew bilingual family: Toward a theoretical framework. Diaspora Indig. Minority Educ. 2010, 4, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wei, L. Transnational experience, aspiration and family language policy. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2016, 37, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duursma, E.; Romero-Contreras, S.; Szuber, A.; Proctor, P.; Snow, C.; August, D.; Calderón, M. The role of home literacy and language environment on bilinguals’ English and Spanish vocabulary development. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2007, 28, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.M.; Lonigan, C.J.; Phillips, B.M.; Farver, J.M.; Wilson, K.D. Influences of the home language and literacy environment on Spanish and English vocabulary growth among dual language learners. Early Child. Res. Q. 2021, 57, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.K.; Mancilla-Martinez, J.; Flores, I.; McClain, J.B. The relationship among home language use, parental beliefs, and Spanish-speaking children’s vocabulary. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 1175–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.A.; Ng, S.C.; Arshad, N.A. The structure of home literacy environment and its relation to emergent English literacy skills in the multilingual context of Singapore. Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 53, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, B.G.; Snow, C.E.; Zhao, J. Vocabulary skills of Spanish—English bilinguals: Impact of mother—child language interactions and home language and literacy support. Int. J. Biling. 2010, 14, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, L.; Tivnan, T. The importance of early vocabulary for literacy achievement in high-poverty schools. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 2008, 13, 426–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendeou, P.; Van den Broek, P.; White, M.J.; Lynch, J.S. Predicting reading comprehension in early elementary school: The independent contributions of oral language and decoding skills. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peets, K.F.; Yim, O.; Bialystok, E. Language proficiency, reading comprehension and home literacy in bilingual children: The impact of context. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suggate, S.; Schaughency, E.; McAnally, H.; Reese, E. From infancy to adolescence: The longitudinal links between vocabulary, early literacy skills, oral narrative, and reading comprehension. Cogn. Dev. 2018, 47, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Bilingualism in Development: Language, Literacy, and Cognition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, E.; Rumiche, R.; Burridge, A.; Ribot, K.M.; Welsh, S.N. Expressive vocabulary development in children from bilingual and monolingual homes: A longitudinal study from two to four years. Early Child. Res. Q. 2014, 29, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Chen, J.; Kim, H.; Chan, P.S.; Jeung, C. Bilingual lexical skills of school-age children with Chinese and Korean heritage languages in the United States. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.H.; Mancilla-Martinez, J. Comparing vocabulary knowledge conceptualizations among Spanish–English dual language learners in a new destination state. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2021, 52, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagarina, N.; Klassert, A. Input dominance and development of home language in Russian-German bilinguals. Front. Commun. 2018, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, G.M.; Griffin, Z.; Peña, E.D.; Bedore, L.M. Longitudinal evidence for simultaneous bilingual language development with shifting language dominance, and how to explain it. Lang. Learn. 2020, 70, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, P.W.; Chen, X.; Cummins, J.; Li, J. Literacy outcomes of a Chinese/English bilingual program in Ontario. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2017, 73, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, K.; Marks, R.A.; Nickerson, N.; Eggleston, R.L.; Yu, C.L.; Chou, T.L.; Tardif, T.; Kovelman, I. What’s in a word? Cross-linguistic influences on Spanish-English and Chinese-English bilingual children’s word reading development. Child Dev. 2022, 93, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, C.S.; Lawrence, F.R.; Miccio, A.W. Exposure to English before and after entry into Head Start: Bilingual children’s receptive language growth in Spanish and English. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2008, 11, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Houwer, A. Environmental factors in early bilingual development: The role of parental beliefs and attitudes. Biling. Migr. 1999, 1999, 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, G.; Calcagno, S.; Tong, R.; Uchikoshi, Y. ‘I think my parents like me being bilingual’: Cantonese–English DLBE upper elementary students mediating parental ideologies about multilingualism. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021, 43, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, C. Parents’ attitudes toward Chinese–English bilingual education and Chinese-language use. Biling. Res. J. 2004, 28, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.E.; Liew, J.; Zou, Y.; Curtis, G.; Li, D. “They’re going to forget about their mother tongue”: Influence of Chinese beliefs in child home language and literacy development. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 50, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.A.; Fogle, L.W. Bilingual parenting as good parenting: Parents’ perspectives on family language policy for additive bilingualism. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2006, 9, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.Y.; Wu, H.; Curby, T.W.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X. Teacher–child interaction quality, attitudes toward reading, and literacy achievement of Chinese preschool children: Mediation and moderation analysis. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E.; Luk, G.; Peets, K.F.; Yang, S. Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism 2010, 13, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Zhou, Q.; Uchikoshi, Y. Heritage language socialization in Chinese American immigrant families: Prospective links to children’s heritage language proficiency. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2018, 24, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, C.S.; Miccio, A.W.; Wagstaff, D.A. Home literacy experiences and their relationship to bilingual preschoolers’ developing English literacy abilities: An initial investigation. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2003, 34, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, È. The impact of home literacy on bilingual vocabulary development. Biling. Res. J. 2021, 44, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Ren, Y. Relationships between home-related factors and bilingual abilities: A study of Chinese–English dual language learners from immigrant, low-income backgrounds. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.; Kan, P.F.; Winicour, E.; Yang, J. Effects of home language input on the vocabulary knowledge of sequential bilingual children. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2019, 22, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, E. Sisters and brothers as language and literacy teachers: Synergy between siblings playing and working together. J. Early Child. Lit. 2001, 1, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, E. ‘Invisible’ teachers of literacy: Collusion between siblings and teachers in creating classroom cultures. Literacy 2004, 38, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obied, V.M. How do siblings shape the language environment in bilingual families? Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2009, 12, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, T.S.; Paradis, J. Home language environment and children’s second language acquisition: The special status of input from older siblings. J. Child Lang. 2020, 47, 982–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheirkhah, M.; Cekaite, A. Siblings as language socialization agents in bilingual families. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2018, 12, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, A.; Howe, N.; Persram, R.J.; Martin-Chang, S.; Ross, H. “I’ll show you how to write my name”: The contribution of naturalistic sibling teaching to the home literacy environment. Read. Res. Q. 2018, 53, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Kan, P.F. The impact of older siblings on vocabulary learning in bilingual children. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2021, 24, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Gutmann, M.L.; Hanson, W.E. Advanced mixed methods research designs. Handb. Mix. Methods Soc. Behav. Res. 2003, 209, 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, L.M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-the Fifth Manual; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, L.M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised; American Guidance Service, Incorporated: Circle Pines, Minnesota, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Liu, H. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Revised Manual; Psychological Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Tsai, C.L.; Chen, Y.J.; Cherng, R.J. Comorbidity of motor and language impairments in preschool children of Taiwan. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 30, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrad, M.; Ghazzali, N.; Boiteau, V.; Niknafs, A. NbClust: An R package for determining the relevant number of clusters in a data set. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 61, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.; Hothorn, T. An Introduction to Applied Multivariate Analysis with R; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, J.; Emmerzael, K.; Sorenson Duncan, T. Assessment of English language learners: Using parent report on first language development. J. Commun. Disord. 2010, 43, 474–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. Family Language Policy: Children’s Perspectives; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lauro, J.; Core, C.; Hoff, E. Explaining individual differences in trajectories of simultaneous bilingual development: Contributions of child and environmental factors. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 2063–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantolf, J.P.; Pavlenko, A. Sociocultural theory and second language acquisition. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 1995, 15, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. Interaction between learning and development. Read. Dev. Child. 1978, 23, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Categories | Total (N = 75) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 34 |

| Male | 41 |

| Mean age (months) | 77.25 |

| School types | |

| Public school | 65 |

| Private school | 10 |

| Canadian-born | 59 |

| New Immigrants | 16 |

| Attending heritage language classes | 39 |

| Participant Code | Age in Months | Gender | Immigration Status (Months in Canada) | PPVT EN Level (Score) | PPVT CH Level (Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A012 | 78 | M | New Immigrant (13) | 1 (48) | 3 (99) |

| A024 | 73 | F | Born in Canada (73) | 3 (94) | 1 (55) |

| A101 | 87 | M | Born in Canada (87) | 5 (142) | 2 (81) |

| A102 | 85 | F | Born in Canada (85) | 2 (81) | 4 (125) |

| CN PPVT | EN PPVT | |

|---|---|---|

| Profile I (N = 34) | M = −0.63, SD = 0.74 | M = 0.53, SD = 0.79 |

| Profile II (N = 41) | M = 0.56, SD = 0.75 | M = −0.45, SD = 0.92 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, G.; Sun, Z.; Zhen, F.; Ji, X.R.; Gunderson, L. Home Literacy Environment and Chinese-Canadian First Graders’ Bilingual Vocabulary Profiles: A Mixed Methods Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315788

Li G, Sun Z, Zhen F, Ji XR, Gunderson L. Home Literacy Environment and Chinese-Canadian First Graders’ Bilingual Vocabulary Profiles: A Mixed Methods Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315788

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Guofang, Zhuo Sun, Fubiao Zhen, Xuejun Ryan Ji, and Lee Gunderson. 2022. "Home Literacy Environment and Chinese-Canadian First Graders’ Bilingual Vocabulary Profiles: A Mixed Methods Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315788

APA StyleLi, G., Sun, Z., Zhen, F., Ji, X. R., & Gunderson, L. (2022). Home Literacy Environment and Chinese-Canadian First Graders’ Bilingual Vocabulary Profiles: A Mixed Methods Analysis. Sustainability, 14(23), 15788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315788