1. Introduction

Governments or public sector organizations use their consistent budgets to buy large quantities of goods, services and public works [

1,

2], for the local economic development or economic stabilization [

3]. According to the World Bank, in 2018, public procurement (PP) accounted for 12% of the global GDP or around USD 11 trillion. Thus, the public sector does not only perform the role of regulator, it is also often considered to be the most important customer within a country [

4].

This purchasing power is used by governments as a strategic tool to achieve environmental, social and economic objectives, in line with national priorities [

5], to influence the practices of private sector organizations [

6] and to promote innovation by creating an economy of scale giving an incentive to technological investment and a guaranteed profit margin [

1].

1.1. COVID-19 Pandemic

The severity of infectious diseases, such as SARS-CoV-2 even in the most technologically developed countries [

7], forced governments all over the world into adopting, almost simultaneously, significant measures, including a general lockdown, border shutdown, closure of production units, and restrictions on air transport networks that lead to a low supply of raw materials [

8]. The crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic has brought extra responsibilities on PP with regards to: first, guarantee the continuity of public services, as well as citizens’ wellbeing, and then to answer growing demands for resilience, innovation and sustainability [

9].

The efficacious and safe vaccine, distributed equitably and rapidly, has been acknowledged as a global public health priority [

10]. It has been considered to be an effective long-term solution to the COVID-19 pandemic, since it is supposed to minimize morbidity and mortality, once a high proportion of the population is immunized [

11], and also to have clinical and socioeconomic benefits [

12].

This requires a vaccination agenda which seeks, as a first step, the protection of the most vulnerable people, as well as the prevention of illness and absenteeism amongst health care workers, ensuring the proper functioning of health services, before widening it to the rest of the eligible population. Achieving worldwide mass vaccination campaigns under particularly constraining circumstances is then a big challenge for the vaccine supply chain, and notably for the procurement function of each country [

13].

The complex nature of the pandemic vaccine supply chain has been substantially covered by research since the onset of the pandemic. Alam et al. (2021) showed that the main constraints the world is currently facing, are manifested in meeting the needs of individual countries, especially given the vastity of the global volume required, as opposed to the current production limitations and the complexity of the context, in terms of logistics and health facilities [

14]. In the same sense, Phelan et al. (2021) highlighted that the vaccine nationalism is another major barrier to equitable vaccine access [

15]. Nevertheless, little effort has been exerted in the area of procurement which is a key link in the COVID-19 vaccine supply chain. As a matter of fact, Gianfredi et al. (2021) presented a review, based on the limited available literature, and concluded that the optimizing costs and avoiding vaccine unavailability, while enhancing equity and global accessibility, is possible through a sustainable vaccine procurement system [

10].

1.2. Public Procurement Strategy

To optimize a procurement process, it is important to select the appropriate procurement strategy [

16], which is all about the choices made in determining what is to be delivered through a particular contract, the procurement and contracting arrangements and how secondary procurement objectives are to be promoted [

17]. Then, the purpose is to meet the internal needs while taking full advantage of the buying power, decreasing the supply vulnerability [

18], and being reflective of the organization’s goals, including sustainable development goals (SDGs) [

4].

The study of Lin et Al (2021) focused, among other things, on the procurement strategy of the influenza vaccine in an uncertain framework, related to supply and demand during the coronavirus pandemic [

19]. However, the supply chain of the COVID-19 vaccine presents a different status quo, compared to the standard vaccine supply chain, in the sense that the purchase for the first one is made by government agencies directly from manufacturers, thus bypassing the typical vaccine supply chain of distributors and wholesalers [

13].

An appropriate public procurement strategy (PPS) is essential for the vaccine distribution and would diminish the adverse impact on SDGs, through reducing the negative environmental impact related to hospitalization from COVID-19 and shifting towards a “prevention-oriented, resource-saving and sustainable world” [

20]. Furthermore, the fair distribution to low- and middle-income countries, would contribute in achieving many of the SDGs, in particular: economic growth, good health and wellbeing, reduced inequalities, peace, justice, strong institutions, and lowering poverty. In that sense, Alam et al. (2021) identified 15 challenges to the vaccine supply chain and their implications on the SDGs [

14].

1.3. COVID-19 Vaccine Contracts

Contracts for the procurement of doses of the COVID-19 vaccines, are negotiated by countries singly or in a group [

10], under confidential purchasing agreements. In this context, the European Union pre-ordered a large volume of vaccines to benefit from the economies of scale. To secure the supply of vaccines, the European Commission negotiated, on behalf of the member states, with pharmaceutical companies engaged in developing the coronavirus vaccine. The doses were then to be divided between the member states, based on their population. An advisory committee was created to review the procurement files, on the basis of various criteria. It consisted of experts in vaccinology, immunology, clinical practice, research and development, and regulation aspects. The members were obliged to maintain the secrecy and have no conflict of interest.

The assessment was based on the analysis of benefits and risks of the vaccine, according to the current and most up to date scientific knowledge, production and supply elements, contractual and legal aspects, and the cost price.

When a file is submitted by the European Union, for a potential purchase of a COVID-19 vaccine, there are two possibilities: 1st—to file with a purchasing obligation and the members states have a deadline to notify whether they wish to opt-out, 2nd—to file with a purchase option that is, that the purchase is not mandatory, and it can be decided upon at a later stage. The first file was submitted by AstraZeneca on August 17, 2020. On the basis of the available scientific data, no critical point making an opt out necessary, was found.

Granting marketing authorization of a vaccine is independent from the process of the procurement consultation. If the marketing authorization process is not successful, the contract is terminated.

In this context of the global race for the COVID-19 vaccine, the coordination of the vaccine strategy in Europe was designed by the European Commission to limit the effects of competition between the member states.

Another example is the Government of Canada, that invested over CAD 1 billion to secure access to the promising vaccine candidates. This included up-front payments that the companies required, to support the vaccine development, testing, and the at-risk manufacturing. Subsequent payments were contingent on the vaccines passing the clinical trials and obtaining the regulatory approval.

Thus, even before any vaccine candidates were approved, many high-income countries ensured their supply of vaccines by purchasing enough doses to vaccinate their inhabitants, numerous times over.

Then, the vaccine makers, among the wealthy nations, took the lead in getting large advance market commitments (AMCs), investing public budgets in the vaccines’ research and development, and exploiting their buying power to conclude contracts with vaccine candidates, in order to get the vaccine first.

It should be noted that encouraging private investment into vaccine research and development, and production capacity is usual through AMCs. That is a legally binding contract between a sponsor and a vaccine developer to commit to purchasing a pre-agreed value or amount of a currently unavailable vaccine [

21]. Then, an AMC diminishes the risks for the producers and guarantees the widespread availability of the vaccine, once licensed [

22].

To obtain a share of the vaccine, countries with a manufactured capacity and a restricted buying power, such as Brazil and India, used another approach. They negotiated with the vaccine candidates, fabrication clauses under advance market commitments.

Other nations, with the capacity to organize clinical trials, tried to benefit from this, to negotiate procurement contracts.

However, several low-income countries, including some African countries, would count entirely on donations, and development loans or grants.

To deal with the gaps with high and low-income countries, COVAX and other alliances invested in the development, production, and acquisition of a broad range of vaccines, to guarantee the fair distribution to low and middle-income countries. The member states buy in at their desired coverage rate, and the vaccines are allocated by the population level.

Conversely, many manufacturing nations are using export restrictions to satisfy their own needs firstly, causing the delay of the delivery for low-income countries.

1.4. Sustainability Assessment (SA)

Due to the emergence of the new variants of the coronavirus, the risk of inefficiency of the COVID-19 vaccine, the extension of the vaccination to the youth, and the strategy of booster shots for an effective protection of citizens, immunization campaigns are likely to be of a longer duration, that is why a sustainable vaccination management is needed [

23]. The research of Klemeš et al. (2021), assessed the energy and environmental footprints, due to the mass vaccination, and showed that they were significant in the vaccination lifecycle in the level of manufacturing, transportation, and storage (cold supply chain accounts for about 69.8% of the energy consumption of the vaccination process), disinfection and waste management [

24]. Moreover, Hasija et al. (2022) have warned about the disruptions that vaccine waste (discarded vials, dry ice for vaccine storage, syringes, needles, personal protective equipment, vaccine packaging materials, based on non-biodegradable plastic, etc.) would generate in the environment and their impact on human health, if no sustainable measures to address the waste management are taken [

25]. Yet, because of the severity of the current situation, the vaccine deployment is seen by decision makers as being of a higher priority than the sustainability matters [

23].

SD involves a set of standards and guiding principles [

26], among the most common of these are the triple bottom line [

27]: environmental integrity, social equity, and economic prosperity [

28]. The 2030 SD Agenda defined the 17 “interrelated” SDGs that cannot be reached without sustainable economic progress [

29]. According to Devuyst et al. (2001), when trying to make society more sustainable, a sustainability assessment (SA) is needed to gather and report information, to undertake new policies and to make decisions [

30,

31]. The purpose is to make sure that “plans and activities make an optimal contribution to sustainable development” [

32].

However, SAs are complex since they imply varied dimensions [

33]. Scientific research is making efforts to develop tools and processes that support SAs [

34]. In this regard, Villeneuve et al. (2017) stated that the assessment should be periodically adjusted to take account of the new data [

33]. Gasparatos (2010) highlighted the fact that analysts are often choosing inappropriate tools for SAs and that the right one shall conform to the values of all stakeholders [

35].

1.5. Case Study of Morocco

The COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures were necessary to limit the spread of the virus. However, they had negative impacts on the economy. a weak export performance, gloomy employment statistics, and a low household consumption, has been a key trend for Morocco in the latter half of 2020, in comparison with 2019.

To break the chain of transmission, to minimize morbidity and mortality, and increase the clinical and socioeconomic benefits, Morocco made the vaccine completely free of charge.

The vaccination campaigns have mainly targeted populations over 12 years of age, according to a vaccination scheme for a total target population of approximately 28,842,000 people, representing about 79.42% (≈80%) of the total population, in order to achieve herd immunity. The priority has been given to several targets, in particular to frontline workers, namely health professionals, public authorities, security forces and national education staff, to elderly persons and to those most susceptible to this virus, before widening it to the rest of the population.

However, establishing a vaccination agenda requires that vaccines are made available in a timely and effective way. Consequently, the proposed case study sheds light on what PPS has to be adopted, theoretically, by Morocco. Subsequently, it will be interesting to know how aligned that strategy is with the approach taken by Morocco, in practice.

Moreover, it is important to note that SD is one of Morocco’s priorities, notably within the framework of buying the COVID-19 vaccine, for a variety of reasons, such as: (1) to comply with the 2011 constitution that provides strong added value in terms of good governance in the public sector, including SD and environmental protection goals, (2) to comply with the 2013 decree of public procurement that integrates, amongst others, sustainability and environmental protection concerns, (3) to recover the pre-pandemic GDP and employment levels, (4) to attract new investors, etc. This stresses the importance of knowing how does this PPS meet the SDGs.

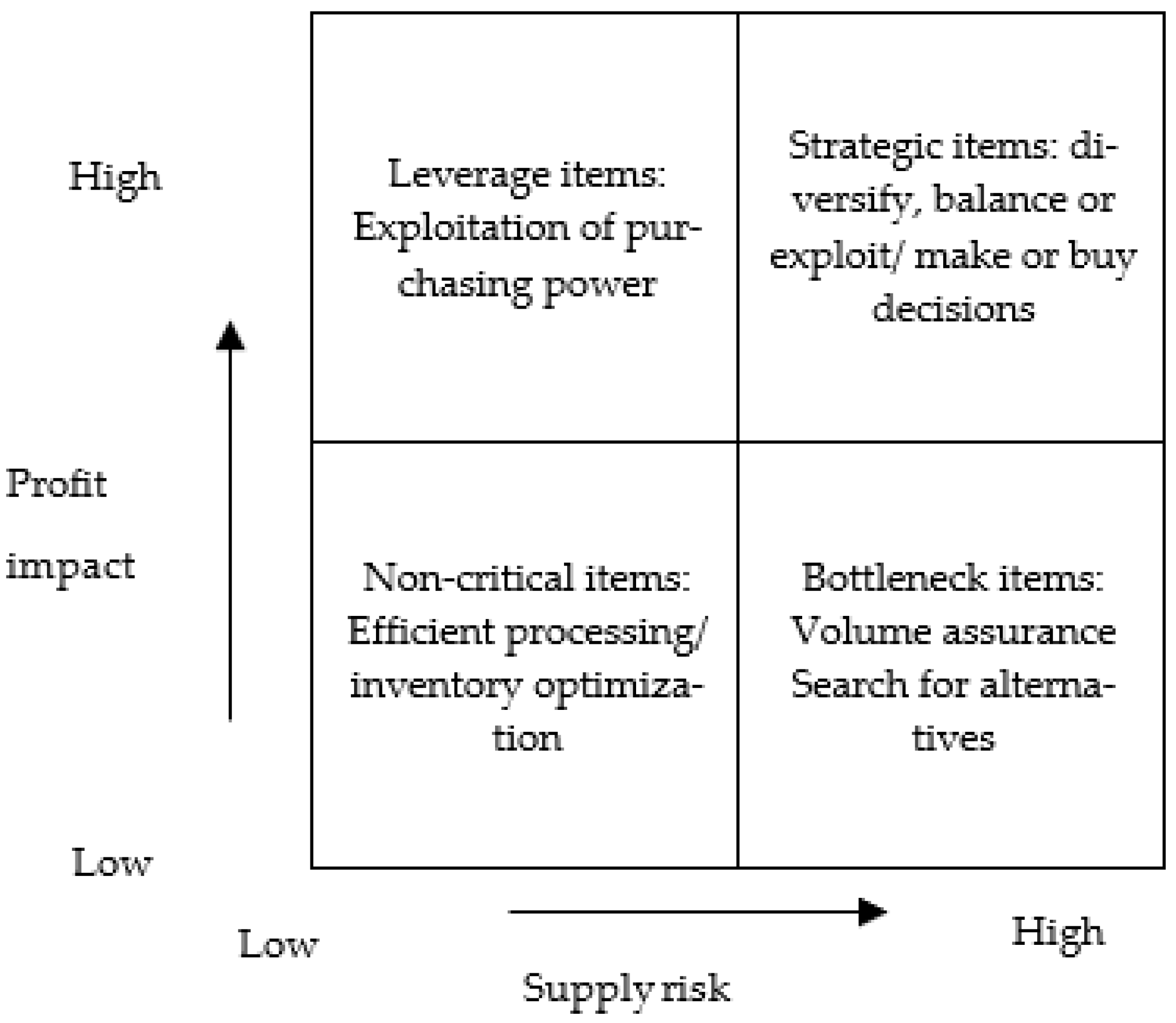

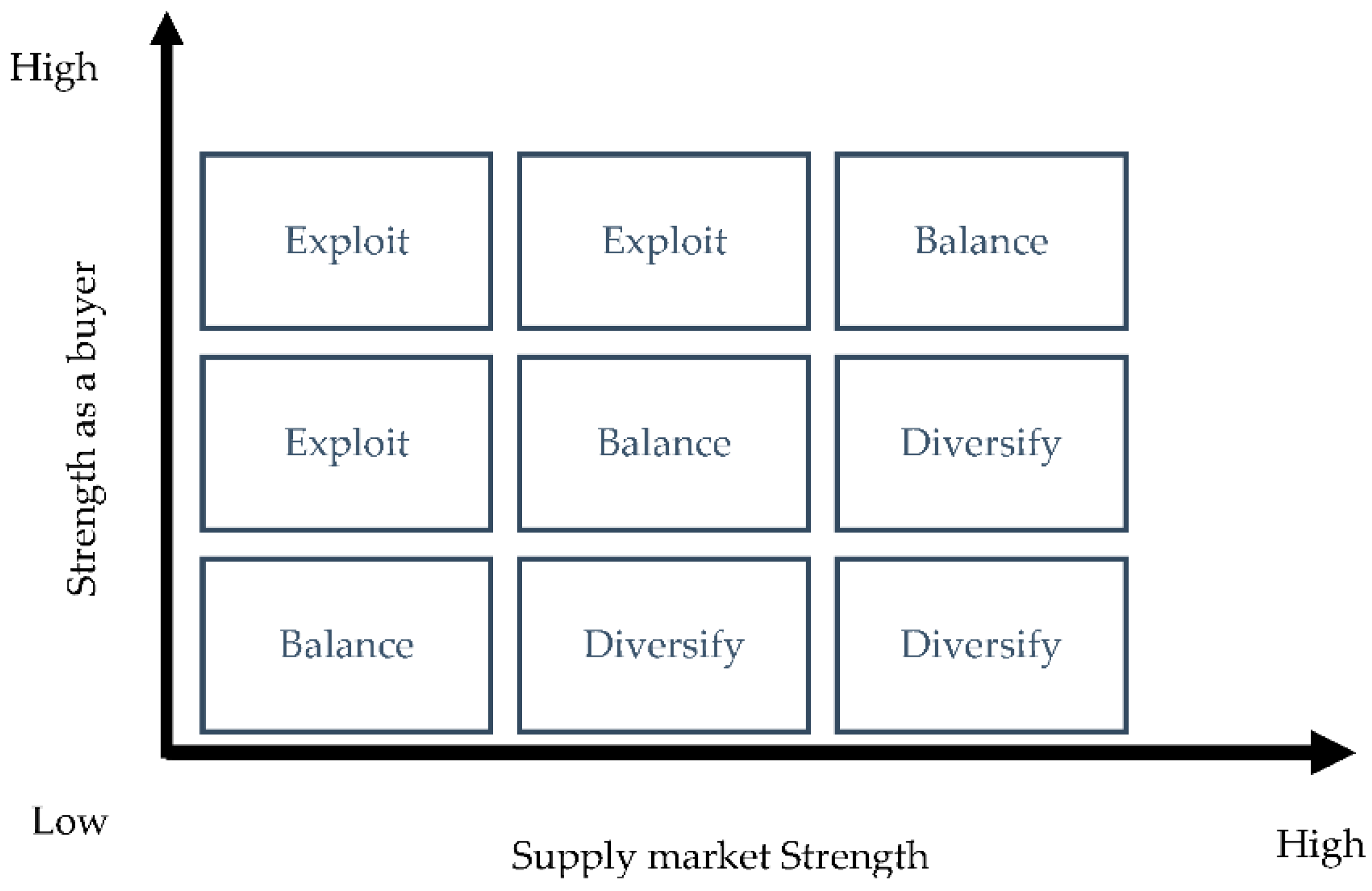

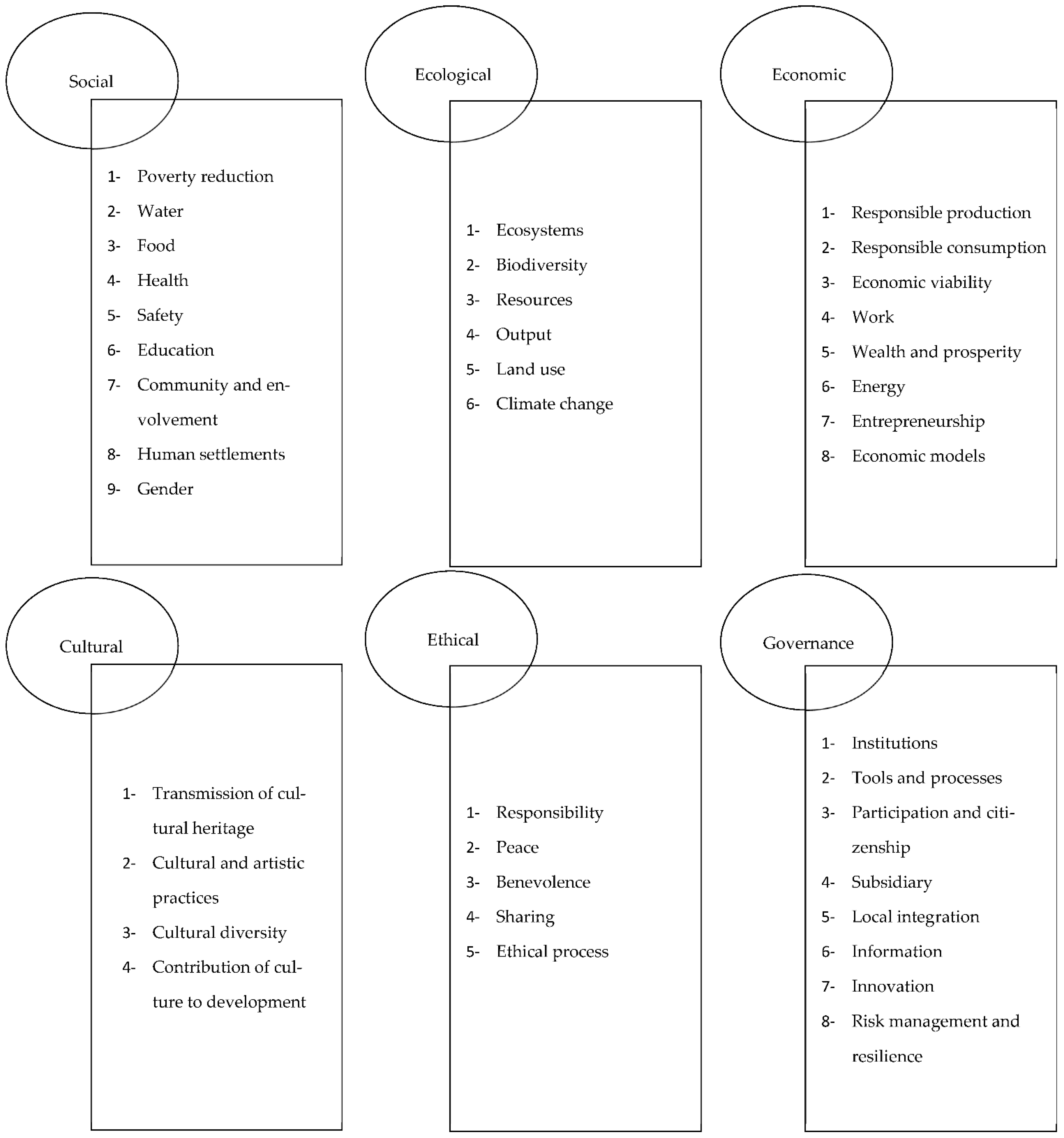

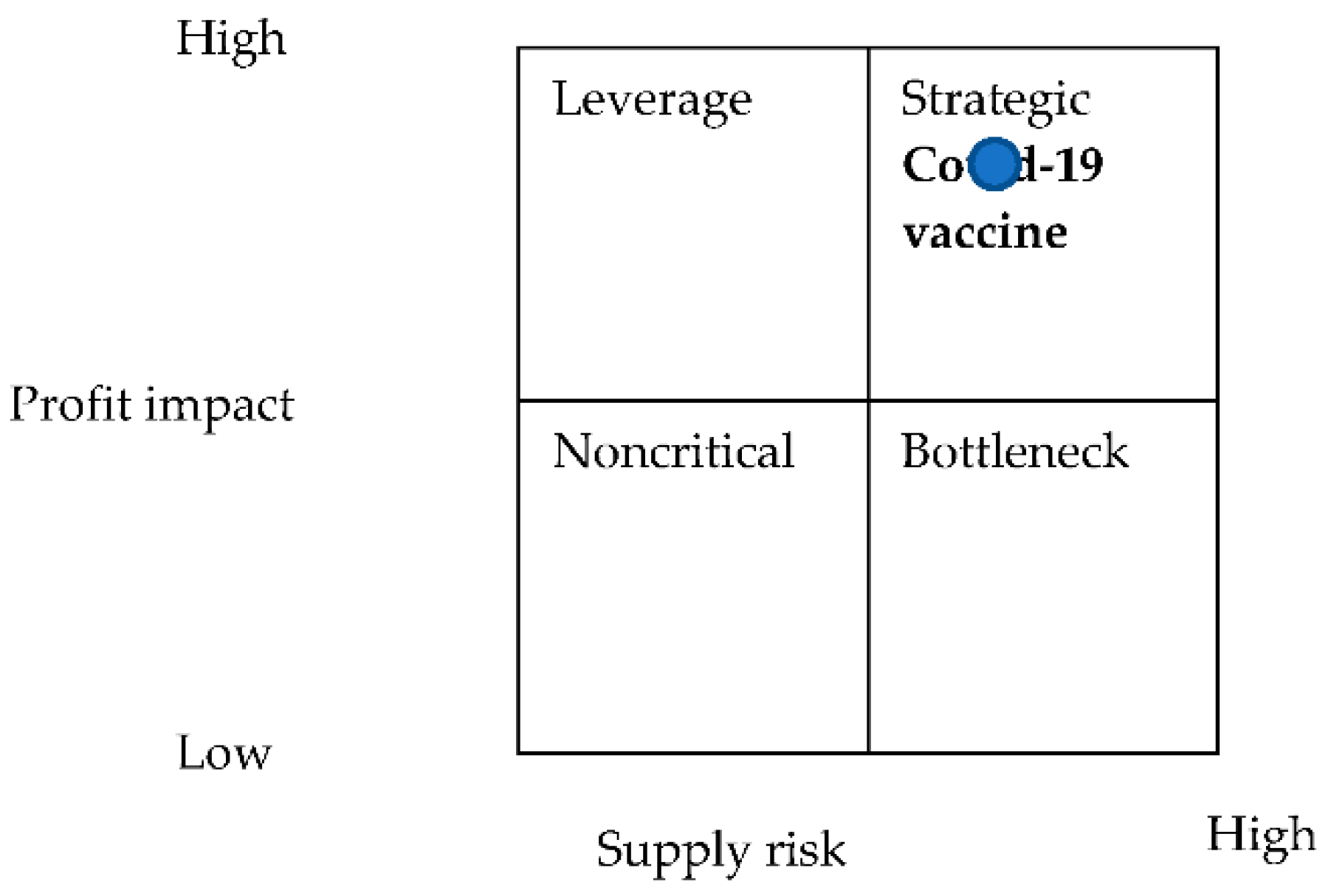

This article aims first, to make a real academic contribution. It is intended to enrich the literature about the elaboration of a public procurement strategy (PPS) and especially in a pandemic context of important global demand and weak supply. A further objective is to address the gap in the existing literature related to the PPS of the COVID-19 vaccine, in general, and particularly in Morocco, and also concerning the gap regarding the sustainability assessment of a PPS. The second aim, is to define how a COVID-19 vaccine PPS should be implemented in a pandemic situation, using mainly Kraljic’s purchasing portfolio model (KPM). The third aim, is to assess the sustainability of that PPS. For this purpose, we use the sustainable development analytical grid [

33]. The case of Morocco, an emerging country [

36], will be considered as an illustration.

The paper sheds light on the following research questions:

RQ1: What strategy has to be adopted for the purchase of a COVID-19 vaccine using the KPM?

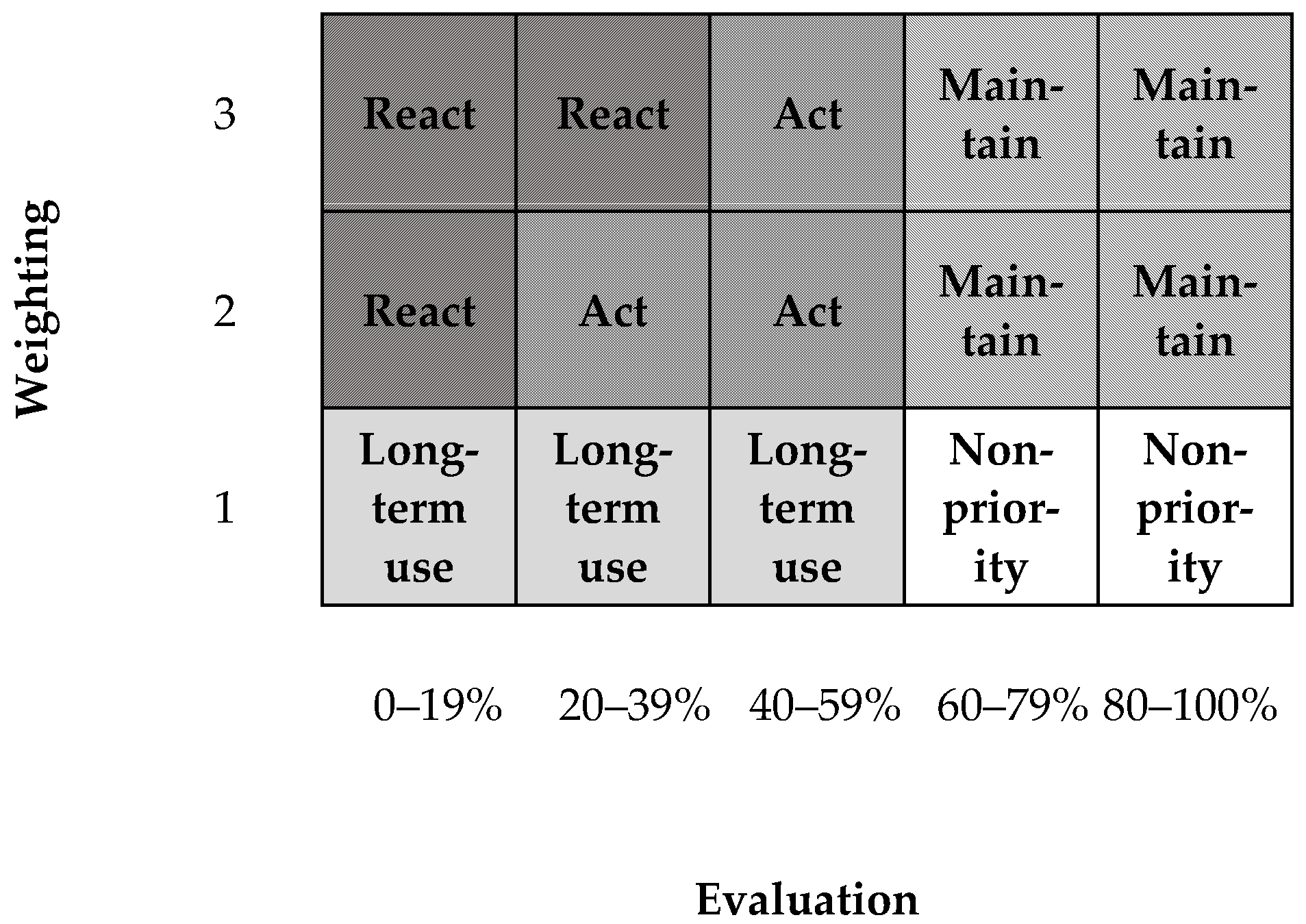

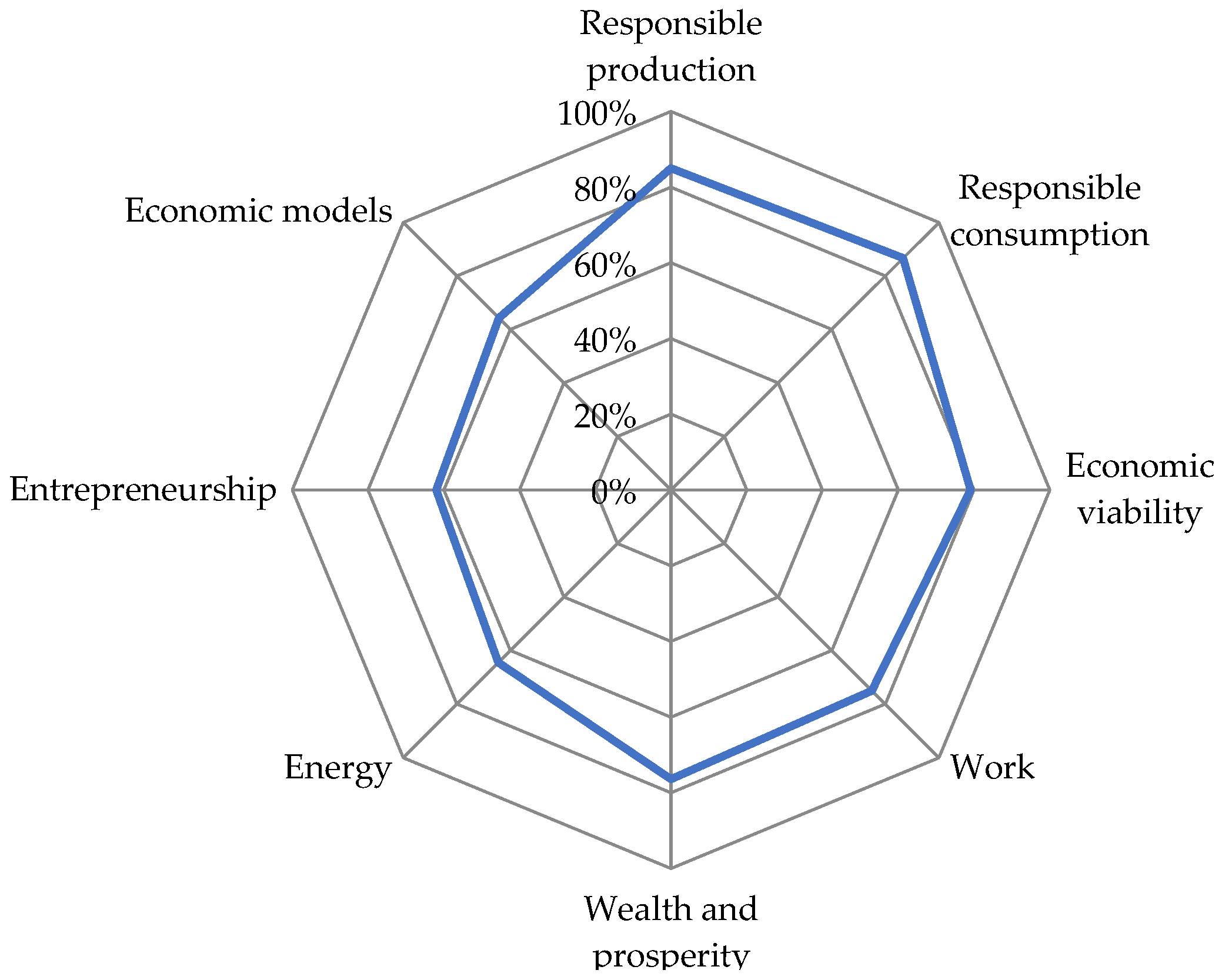

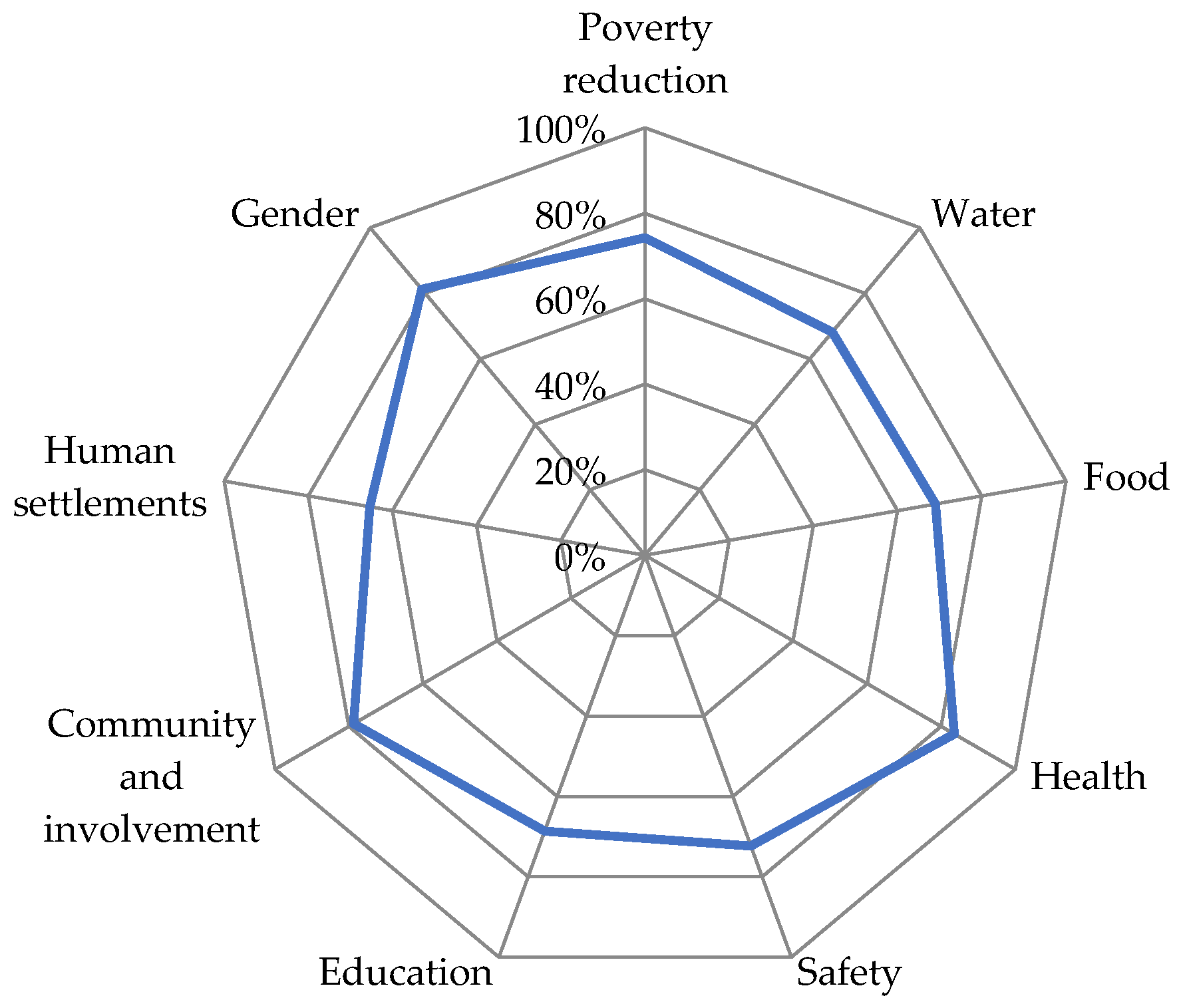

RQ2: How does the PPS meet the SD objectives?

RQ3: What PPS has to be adopted by Morocco, as a case study? Is that theoretical strategy aligned with the approach taken by Morocco, in practice?

RQ4: How does the strategy adopted by Morocco meet sustainability?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The following section presents the methodology adopted. Subsequently, we focus on the case study of Morocco, to evaluate the effectiveness of the methodology proposed for setting a PPS and managing the relationships with the vaccine suppliers, then we assess that strategy, in terms of sustainability, to close with concluding remarks.

4. Discussion

The main objective, was to be able to obtain vaccine doses to save lives, in a pandemic context, characterized by an upsurge in demand and the scarcity of supply (vaccine availability being treated as having a much higher priority than cost). In order to have a stronger negotiating position, the Moroccan government used its diplomatic relationships with vaccine producing countries, as part of its procurement strategy. This has allowed Morocco to become the first African country to start a major vaccination campaign.

Morocco had also been involved in the clinical trials of Sinopharm’s vaccine, to guarantee its share of it. The COVID-19 vaccine campaign was initially scheduled to start in November 2020 but had to be postponed for two months (29 January 2021), due to delivery delays. In fact, at this time, the market was at its peak and Morocco’s bargaining power as a buyer was very low.

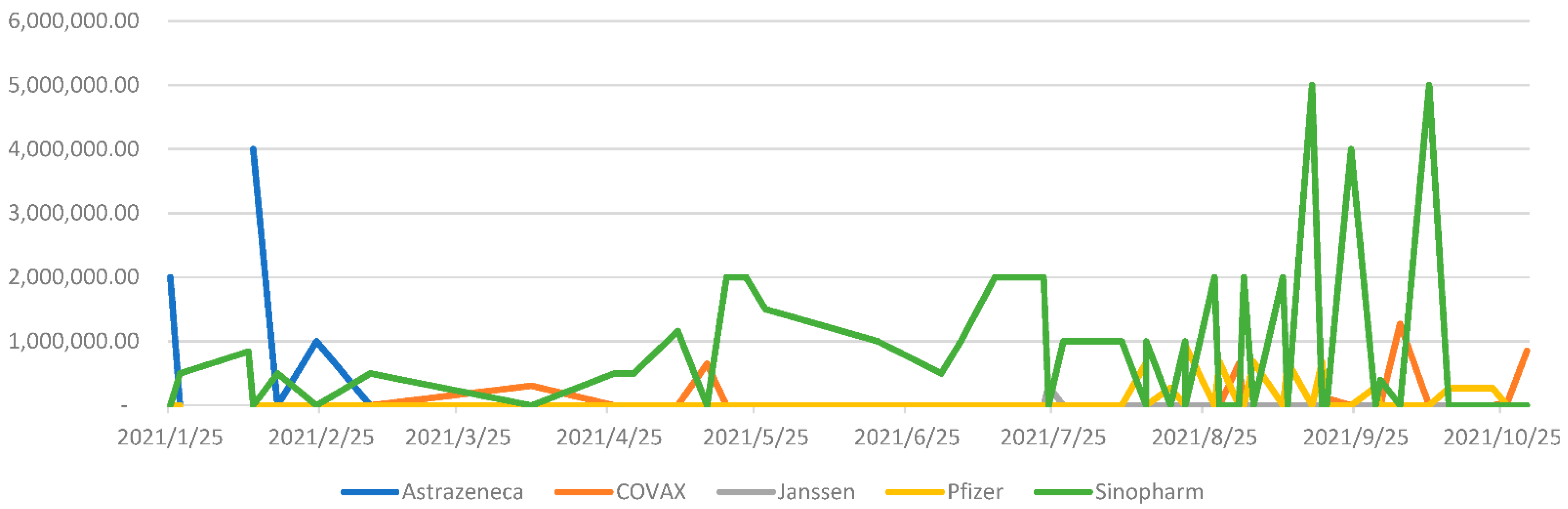

Deliveries from AstraZeneca were interrupted, due to the health situation in India, whereas deliveries from Sinopharm started slowly, due to intense competitive rivalry, then turned relatively regular. That explains Morocco’s strategic move (starting from the 13 August 2021), as they introduced Pfizer as a new additional supplier, as an attempt to diminish the exclusive buying power of Sinopharm.

Morocco is currently particularly relying on Sinopharm and Pfizer because they give visibility of the delivery schedule (

Figure 15).

Furthermore, Morocco has launched a project for bringing production and syringe filling of the vaccines in house, including the COVID-19 vaccine, in response to the potential risks linked to: (1) the emergence of new viral variants, resulting from new strains and virus mutations, (2) vaccine scarcity, (3) newly emerging epidemics. Morocco hopes to improve the production capacity for a more sustainable and reliable vaccine supply. This is a strategic investment, as it would enable self-sufficiency, access to the African markets, and above all to the creation of an ecosystem of industries of biotechnology and biosimilars that will involve boosting skills and attracting potential investors.

Thus, in reply to RQ3, Morocco has so far complied with the first scenario of the PPS of the COVID-19 vaccine described earlier.

It should be noted that despite the competitive rivalry, until March 23, 2022, Morocco was able to fully vaccinate (two doses) 63.3% of its population.

The main aim, at present, must be to switch from the strategic quadrant to the leverage quadrant, since leverage purchases are easy to manage, despite their strategic importance [

49].

Due to the COVID-19 crisis, 1.058 million people are facing a major threat, as they are on the verge of joining the vulnerable into poverty [

50]. Morocco adopted its PPS to ensure economic recovery, reduce poverty, and enable citizens to have access to basic needs, such as water, food, and energy. Knowing that, the disruption of the global supply chains and international maritime transport, caused the price increase of some basic foodstuffs.

Education has also been impacted negatively by the crisis. During the lockdown, 18% of households (29% of which in rural areas) could not participate in distance-learning classes. Then, the PPS is of vital importance to protect the gains made so far on school enrolment and literacy.

However, the COVID-19 vaccine rollout created a false sense of security. A degree of relaxation in the application of shielding measures was observed. The arrival of new variants generates an explosion in the number of cases. Thus, it is important to enhance the communication strategy with an approach, focused on each class, to increase awareness on protection measures.

To ensure the COVID-19 vaccine supply, significant efforts were made regarding governance, such as the creation of partnerships between different stakeholders. The appointment scheduling system of the COVID-19 vaccine ensures a successful organization and limits the opportunities for corruption.

An immunization awareness campaign was developed on multiple media platforms. However, it is important to review the project communication strategy through adopting a better targeted and more positive approach and opting for more transparency, in particular for information related to the vaccine procurement process. A better tailored health communication is also needed to face misinformation about the vaccine, vaccine hesitancy and antivax movements.

With regard to the environmental pillar, the knowledge and experience of Morocco are used for the waste management of the vaccine. Renewable energy is a major component of the Moroccan energy strategy. This is an opportunity to achieve SD along climate-resilient and low greenhouse gas emission-intensive paths, limiting the use of fossil fuels, investing in less harmful refrigerants and recycling empty vaccine vials.

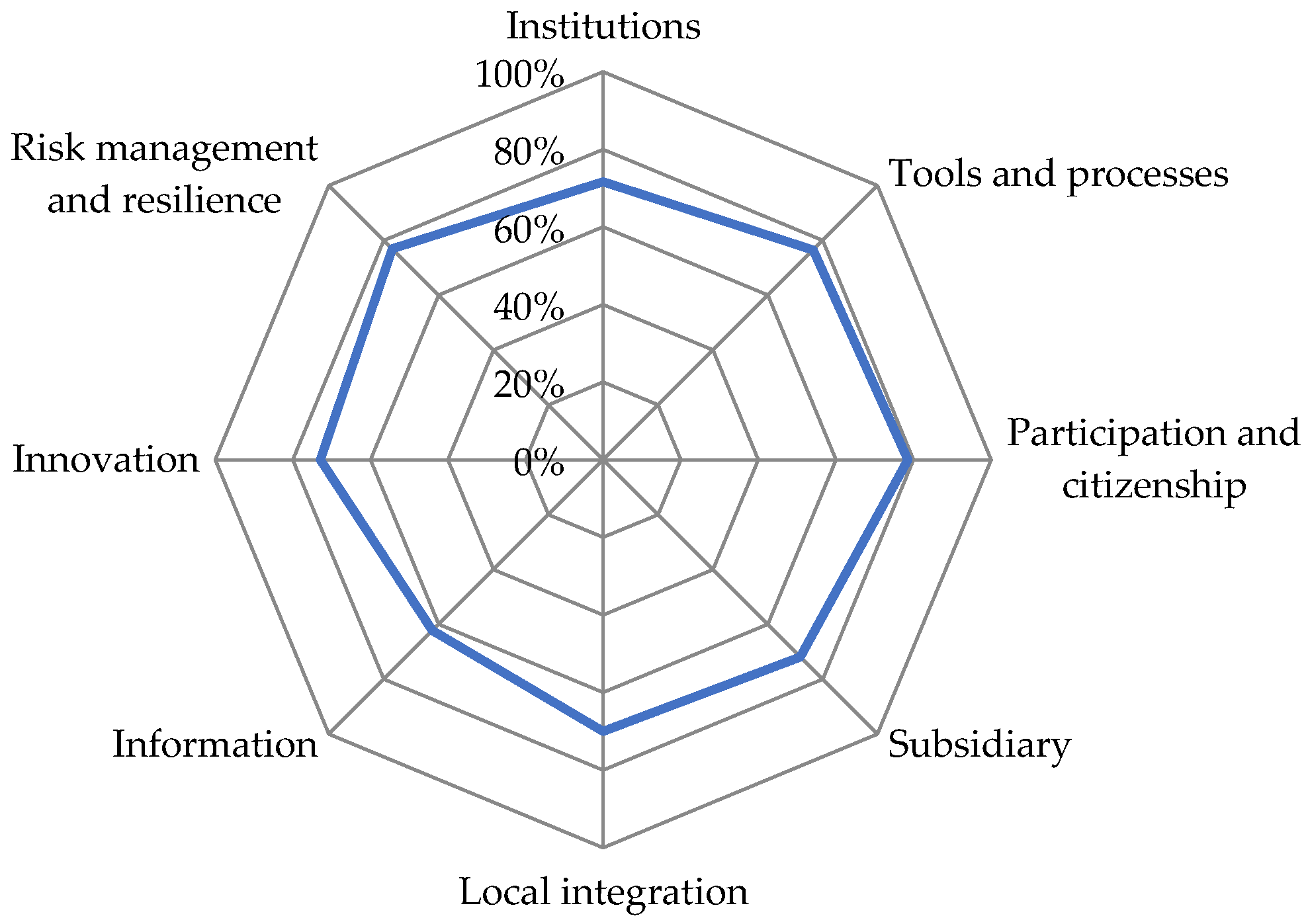

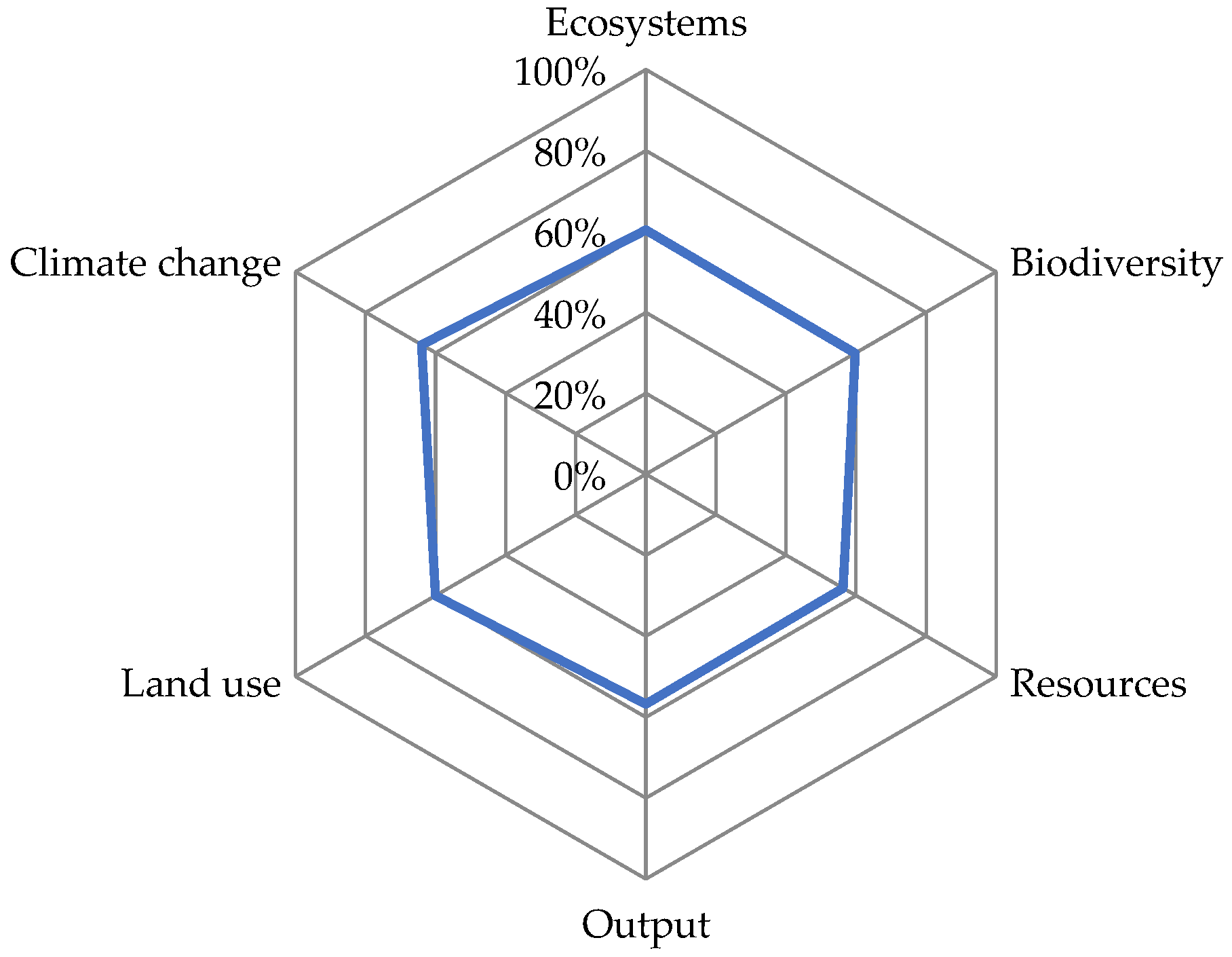

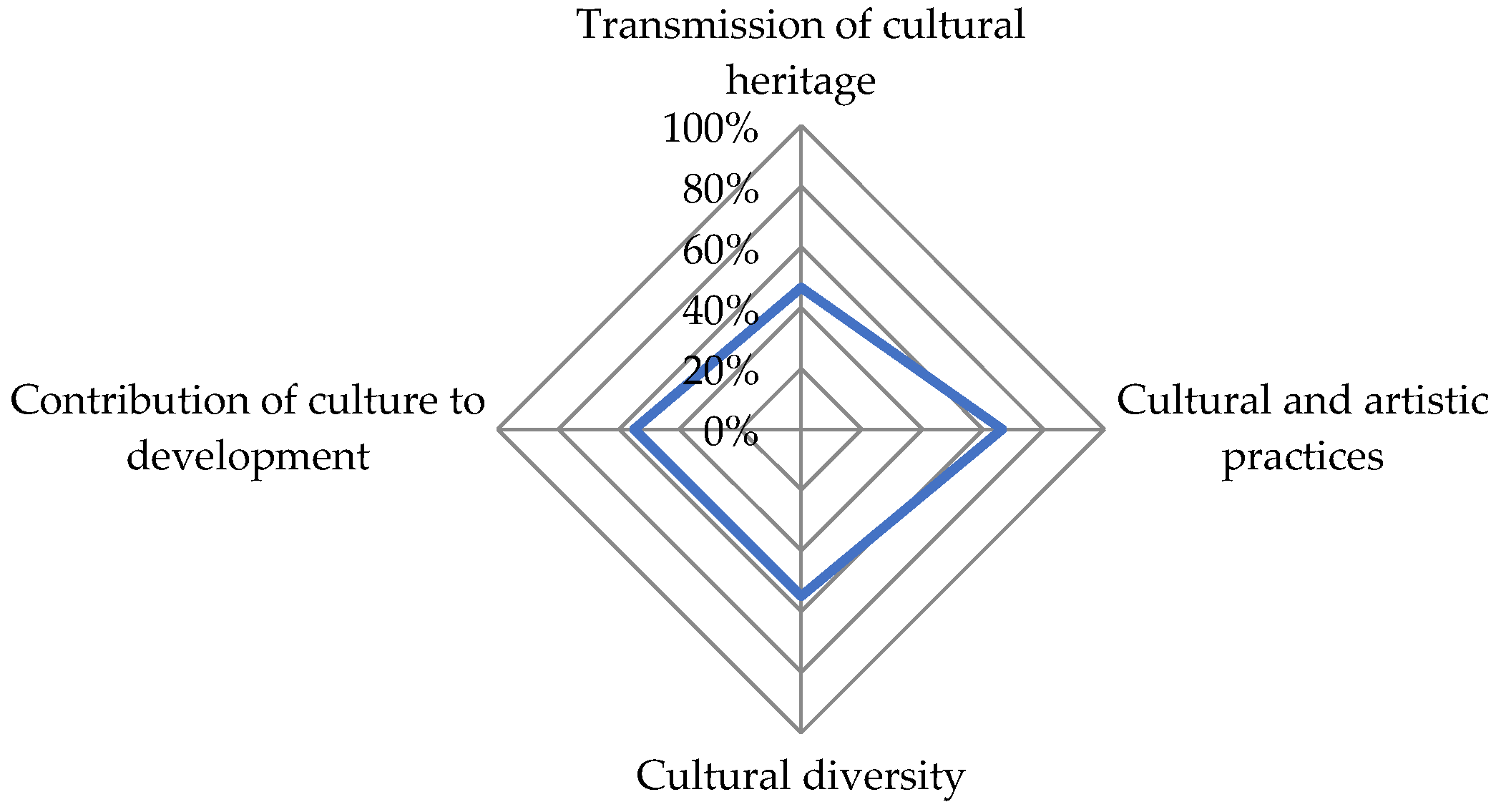

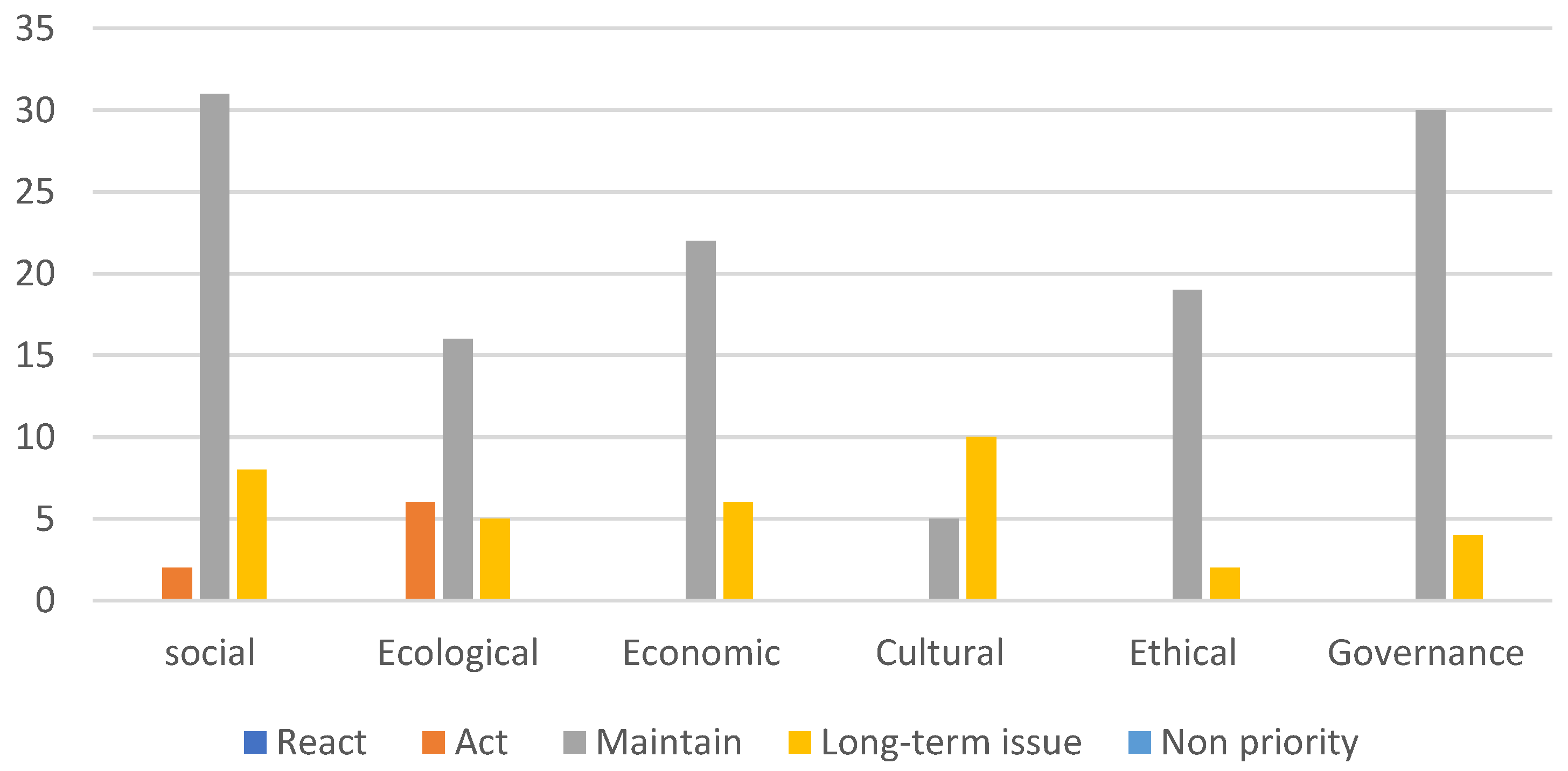

To answer RQ4, the SA shows that the PPS of the COVID-19 vaccine covers satisfactorily 74% of the 166 SDGs addressed by the SDAG. Five percent of the objectives immediately need an additional plan of action, while 21% of issues can only be dealt with over the longer term, given the urgency of the economic and social recovery.

In the same framework, for a better assessment, it would be appropriate to make a comparison with another similar strategy, in terms of the context and needs.

Furthermore, given the dynamic nature of the SA, the PPS needs to be periodically evaluated, in order to follow up, adjust, correct and maintain its accomplishments.

5. Conclusions

The article provides useful insights for other developing countries, in order to set up a COVID-19 vaccine PPS and to assess its sustainability. It is also valuable for academics, public purchasing managers, and all the stakeholders involved in the public procurement process, who need an overview about how to develop a PPS, in times of crisis or scarcity.

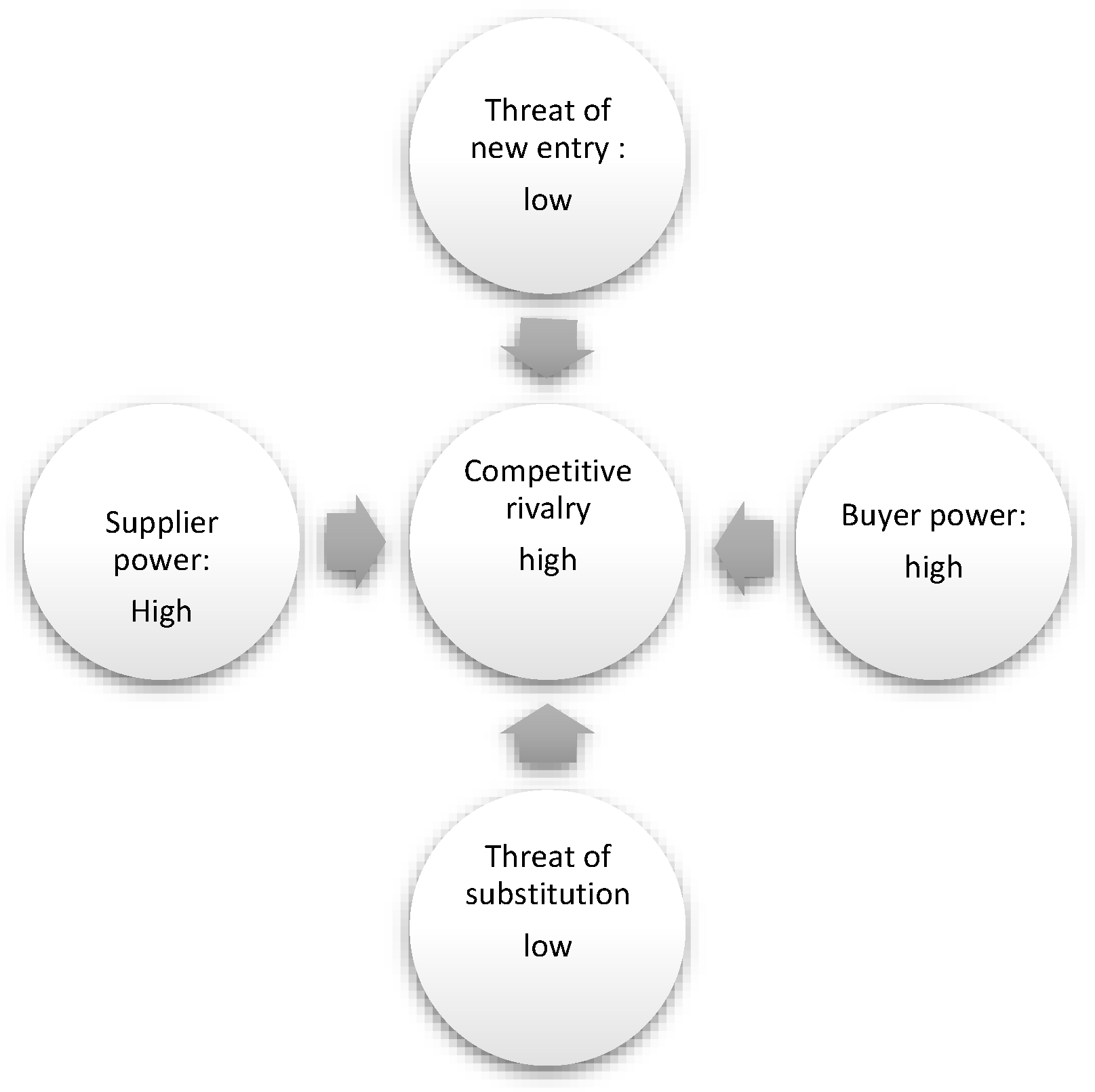

The first purpose of the case study was to determine the best purchasing strategy to be adopted by Morocco for the COVID-19 vaccine, using Kraljic’s portfolio matrix (KPM). It was found that the PPS should be based on three different scenarios, according to the worldwide demand, whose progress was assessed via Porter’s five forces analysis.

The study reported that Morocco’s approach is up to date, in line with the first scenario of the theoretical strategy, namely the diversification to reduce the dependence on a single supplier, and bringing the production in house, in the framework of the ongoing project of the production and syringe filling of vaccines, including the COVID-19 vaccine.

Defining the purchasing strategy of the COVID-19 vaccine that should be adopted by Morocco, provides another illustration of the power of the KPM, as a dynamic and flexible tool that needs to be reviewed frequently, because of the dynamic nature of the markets that can change the supply situation significantly in short time periods.

The procurement strategy was then assessed, in terms of sustainability, and using the SDAG, it would appear that the strategy provides coverage for most of the objectives, but considering the urge for an economic reboot, some fields are to be prioritized while others would only be considered later on in a long-term vision. It would also appear that the SDAG brings in some improvement options, including some clues that seem to have appeared on multiple occasions reaching multiple dimensions. A periodical sustainability assessment is a key factor in achieving a continuous improvement of the strategy.

However, several important lessons could be drawn from the PPS adopted by Morocco and developed in this paper: aware of the key role of immunization to save human lives and to restart the economy, Morocco established a PPS to purchase an adequate number of COVID-19 vaccines, in a pandemic context characterized by very strong global demand and an extremely short supply of doses. Then, achieving the first step of the strategy, which consists of diversification to decrease the dependence on a single supplier, wasn’t easy. To do that, Morocco used its instruments and diplomatic relations with vaccine producing countries to be in a stronger negotiating position, Morocco has also hosted the clinical trials of Sinopharm’s vaccine, to guarantee its share of it.

To ensure vaccine sovereignty, Morocco set up a first production unit for a more sustainable and reliable vaccine supply, as a second step of its PPS. The essential aim of this investment is self-sufficiency and to better respond to the needs of vaccines of the African continent.

The actions taken by Morocco in the procurement of the COVID-19 vaccine have made it possible to turn pandemic challenges into an opportunity to create an ecosystem of industries of biotechnology and biosimilars.

In future research, the PPS should be updated in accordance with supply and demand, the sustainability assessment should be actualized too. This paper can be regarded as a starting point for further discussions about drivers and barriers of sustainable procurement in Morocco, that could be enriched by a benchmark [

51], and sustainability assessment of strategic projects.