Social Inclusion Concerning Migrants in Guangzhou City and the Spatial Differentiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Area and Data Collection

Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Social Inclusion Indicator System

4. Results

4.1. Overall Characteristics of Guangzhou’s Social Inclusion

4.2. Group Differences of Social Inclusion

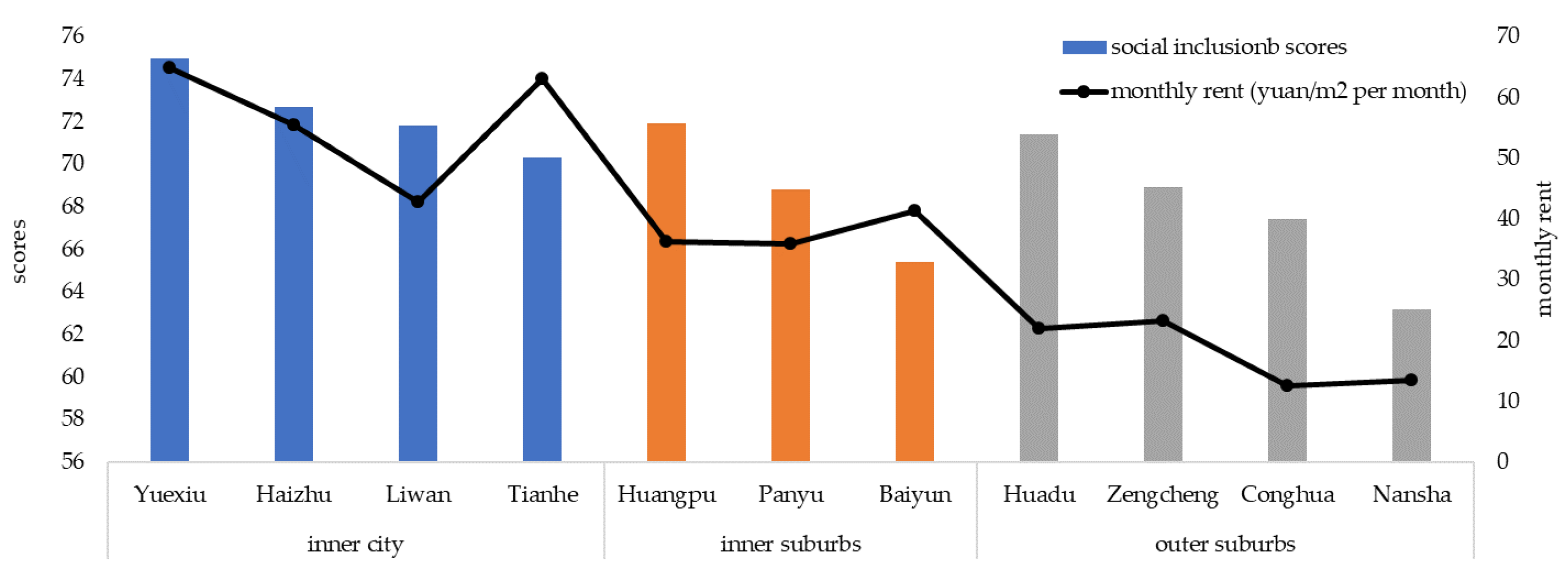

4.3. Spatial Differentiation of Urban Residents’ Social Inclusion

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martiniello, M.; Rea, A. The concept of migratory careers: Elements for a new theoretical perspective of contemporary human mobility. Curr. Sociol. 2014, 62, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.C.; Ngai, P.; Chan, J. The role of the state, labour policy and migrant workers’ struggles in globalized China. In Globalization and Labour in China and India; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, A.G.O.; Chen, Z. From cities to super mega city regions in China in a new wave of urbanisation and economic transition: Issues and challenges. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 636–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, N. Building talented worker housing in Shenzhen, China, to sustain place competitiveness. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, W. Perspectives of socio-spatial differentiation from soaring housing prices: A case study in Nanjing, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraydin, A.; Tasan-Kok, T.; Vranken, J. Diversity matters: Immigrant entrepreneurship and contribution of different forms of social integration in economic performance of cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities 2017, 60, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonte, R. Social inclusion/exclusion: Dancing the dialectic. Health Promot. Int. 2004, 19, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R. Teda chengshi bendi jumin dui wailai renkou de shehui baorongdu: Celiang yu pingjia—yi beijing weili [Social inclusion of migrant population by native residents of Megalopolis: Measurement and evaluation and a case study of Beijing]. J. Soc. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2017, 46, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Lun shehui baorong li [On social tolerance]. Theory Reform 1994, 2, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Tan, Y.; Chai, Y. Neighbourhood-scale public spaces, inter-group attitudes and migrant integration in Beijing, China. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 2491–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, L.J.; Xue, D. An African enclave in China: The making of a new transnational urban space. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2009, 50, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liu, Y.; An, N.; Zhao, Q. Kuaguo yimin de difanggan yanjiu: Yi zai sui feizhou yimin weili [Study on Transnational Migrants’ Sense of Place: A Case Study of African Migrants in Guangzhou]. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 37, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jing Newspaper. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1663799843174675808&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Lin, Y.; De Meulder, B.; Wang, S. Understanding the ‘village in the city’in Guangzhou: Economic integration and development issue and their implications for the urban migrant. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 3583–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, L.M. Anti-immigrant prejudice in Europe: Contact, threat perception, and preferences for the exclusion of migrants. Soc. Forces 2003, 81, 909–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. The marginality of migrant children in the urban Chinese educational system. Brit. J. Sociol. Educ. 2008, 29, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannestad, P. Immigration and welfare states: A survey of 15 years of research. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2007, 23, 512–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.C.; Liu, H.Q. Bendi jumin dui waiguo yimin de yinxiang jiegou jiqi shengchan jizhi —yixiang zhendui Guangzhou bendi jumin yu feizhou yimin de yanjiu [The impression structure of local residents towards foreign immigrants and its production mechanism: A study of Guangzhou local residents and African immigrants]. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2016, 36, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Systematizing the predictors of prejudice. In Racialized Politics: The Debate about Racism in America; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000; pp. 280–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sides, J.; Citrin, J. European opinion about immigration: The role of identities, interests and information. Brit. J. Polit. Sci. 2007, 37, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Immigration, fertility, and human capital: A model of economic decline of the West. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2010, 26, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Rose, N. Urban social exclusion and mental health of China′s rural-urban migrants–A review and call for research. Health Place 2017, 48, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W.; Clark, K.; Pettigrew, T. The Nature of Prejudice. 1954. Available online: https://faculty.washington.edu/caporaso/courses/203/readings/allport_Nature_of_prejudice.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Dovidio, J.F.; Gaertner, S.; Kawakami, K.; Hodson, G. Why can’t we just get along? Interpersonal biases and interracial distrust. Cultural, Diversity. Ethn. Min. Psychol. 2002, 8, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Reactions toward the new minorities of Western Europe. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U.; Christ, O.; Pettigrew, T.F.; Stellmacher, J.; Wolf, C. Prejudice and minority proportion: Contact instead of threat effects. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 2006, 69, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberger, J.; Hewstone, M. Inter-ethnic contact as a predictor of blatant and subtle prejudice: Tests of a model in four West European nations. Brit. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 36, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.H.; Jiang, H. Nongmingong chengshi shiying yanjiu de jizhong lilun shijiao [Several theoretical perspectives in the research on urban adaptation of migrant workers]. Explor. Free Views 2009, 24, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gidley, J.; Hampson, G.; Wheeler, L.; Bereded-Samuel, E. Social inclusion: Context, theory and practice. Australas J. Univ. -Community Engagem. 2010, 5, 6–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, P.; Davis, F.A. Social capital, social inclusion and services for people with learning disabilities. Disabil. Soc. 2004, 19, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Integrated public education, fertility and human capital. Educ. Econ. 2014, 22, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R. Access to social insurance in urban China: A comparative study of rural–urban and urban–urban migrants in Beijing. Habitat. Int. 2014, 41, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Xie, K. Privileged daughters? Gendered mobility among highly educated Chinese female migrants in the UK. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, T. The effectiveness of community sports provision on social inclusion and public health in rural China. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He 2020, 17, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.H.; Luo, Y.P. Chengshi shehui baorong jiqi yingxiang yinsu yanjiu [Research on Urban Social Inclusion and Its Influencing Factors]. Soc. Sci. J. 2014, 35, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Guangzhou 7th National Pupulation Census, Guangzhou Statistics Bureau. Available online: http://tjj.gz.gov.cn/stats_newtjyw/tjsj/tjgb/glpcgb/content/post_8540184.html (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Guangzhou Statistical Yearbook 2021. Guangzhou Statistics Bureau. 2022. Available online: https://lwzb.gzstats.gov.cn:20001/datav/admin/home/www_nj// (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Huxley, P.; Thornicroft, G. Social inclusion, social quality and mental illness. Brit. J. Psychiatry 2003, 182, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilles, D.; Diego, P. Nursery Cities: Urban Diversity, Process Innovation, and the Life Cycle of Products. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1454–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.; Gates, G. Technology and tolerance: The importance of diversity to high-technology growth. In The City as an Entertainment Machine; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kahanec, M.; Tosun, M.S. Political economy of immigration in Germany: Attitudes and citizenship aspirations. Int. Migr. Rev. 2009, 43, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, Y.N. Citizenship, immigration, and the European social project: Rights and obligations of individuality. Brit. J. Sociol. 2012, 63, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radtke, F.O. Multiculturalism in Germany: Local management of immigrants’ social inclusion. Int. J. Multicult. Soc. 2003, 5, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, G.E.; Oppido, S. Inclusive cities for intercultural communities. European experiences. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.H.; Li, Z.B. Jiuye zhiliang, chengshi shehui barong yu nongmingong jiankang yanjiu [On employment quality, urban social inclusion and the health status of migrant workers]. J. East China Norm. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Haubert, J.; Fussell, E. Explaining pro--immigrant sentiment in the U. S.: Social class, cosmopolitanism, and perception of immigrants. Int. Migr. Rev. 2006, 40, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayda, A.M. Who is against immigration? A cross-country investigation of individual attitudes toward immigrants. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 88, 510–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, C.R.; Tsai, Y.M. Social factors influencing immigration attitudes: An analysis of data from the general social survey. Soc. Sci. J. 2001, 28, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Shenasi, S.; Xu, T. Chinese attitudes toward African migrants in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Sociol. 2016, 46, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xue, D.; Lyons, M.; Brown, A. Ethnic enclave of transnational migrants in Guangzhou: A case study of Xiaobei. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2007, 63, 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Lyons, M.; Brown, A. China’s ‘Chocolate City’: An ethnic enclave in a changing landscape. Afr. Diaspora 2012, 5, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Duan, C.R.; Zhu, X. Effect of social support on psychological well-being in elder rural-urban migrants. Pop J. 2016, 38, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

| Sample Size | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4548 | 47.30% |

| Female | 5059 | 52.70% |

| Length of Residence in Guangzhou | ||

| Less than 1 year | 572 | 6% |

| 1–5 years | 1545 | 16.10% |

| 5–10 years | 1089 | 11.30% |

| More than 10 years | 6401 | 66.60% |

| Age | ||

| Under 20 | 184 | 1.90% |

| 20–29 | 2474 | 25.80% |

| 30–39 | 3464 | 36.10% |

| 40–49 | 2779 | 28.90% |

| 50–59 | 688 | 7.20% |

| 60–69 | 14 | 0.10% |

| Over 70 | 4 | 0.04% |

| Educational Background | ||

| Junior high school degree or below | 874 | 9.10% |

| Senior high school/technical secondary school | 1653 | 17.20% |

| Associate degree | 2536 | 26.40% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4122 | 42.90% |

| Graduate degree or above | 432 | 4.50% |

| Work Location by Administrative District | ||

| Baiyun | 2672 | 27.81% |

| Nansha | 1346 | 14.01% |

| Yuexiu | 1026 | 10.68% |

| Tianhe | 776 | 8.08% |

| Haizhu | 733 | 7.63% |

| Huadu | 715 | 7.44% |

| Panyu | 644 | 6.70% |

| Zengcheng | 552 | 5.75% |

| Conghua | 536 | 5.58% |

| Huangpu | 444 | 4.62% |

| Liwan | 163 | 1.70% |

| Job Levels | ||

| General staff | 6870 | 72% |

| Middle managers | 2151 | 22% |

| Senior management | 586 | 6% |

| Annual Household Income (unit: ten thousand yuan) | ||

| 0~5 | 1777 | 18.50% |

| 5~7 | 1576 | 16.40% |

| 7~10 | 1614 | 16.80% |

| 10~20 | 2392 | 24.90% |

| 20~30 | 1249 | 13% |

| 30~50 | 788 | 8.20% |

| 50~100 | 173 | 1.80% |

| More than 100 | 48 | 0.50% |

| Residence by Administrative Division | ||

| Baiyun | 2643 | 27.51% |

| Nansha | 1205 | 12.55% |

| Panyu | 842 | 8.76% |

| Haizhu | 799 | 8.31% |

| Huadu | 766 | 7.97% |

| Tianhe | 755 | 7.86% |

| Yuexiu | 685 | 7.13% |

| Zengcheng | 570 | 5.93% |

| Conghua | 545 | 5.67% |

| Huangpu | 413 | 4.30% |

| Liwan | 384 | 3.99% |

| Index | Score |

|---|---|

| Social inclusion of migrants from other countries | 72.75 |

| Social inclusion of migrants from other provinces | 80.2 |

| Social inclusion and acceptance of different cultures | 73.0 |

| Social inclusion and consideration of vulnerable groups | 69.5 |

| Overall evaluation of social inclusion | 68.4 |

| Administrative Districts | Attitudes toward People from Other Provinces | Attitudes toward Foreigners | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natives with Guangzhou Hukou | Migrants with Guangzhou Hukou | Natives with Guangzhou Hukou | Migrants with Guangzhou Hukou | |

| Baiyun | 75.8 | 82.2 | 70.4 | 70.6 |

| Conghua | 78.0 | 86.6 | 73.6 | 75.5 |

| Panyu | 79.0 | 83.0 | 75.0 | 75.8 |

| Haizhu | 74.3 | 82.3 | 70.9 | 69.9 |

| Huadu | 78.5 | 88.0 | 73.3 | 76.3 |

| Huangpu | 75.3 | 85.8 | 69.9 | 74.6 |

| Liwan | 73.1 | 83.2 | 70.6 | 73.6 |

| Nansha | 75.3 | 84.4 | 73.4 | 76.7 |

| Tianhe | 77.6 | 83.8 | 73.5 | 73.1 |

| Yuexiu | 74.9 | 84.0 | 70.5 | 72.5 |

| Zengcheng | 82.7 | 86.4 | 78.7 | 77.3 |

| Sum | 76.6 | 83.8 | 72.4 | 73.1 |

| Social Inclusion Concerning Migrants | Social Inclusion and Acceptance of Different Cultures | Social Inclusion and Consideration of Vulnerable Groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real estate industry | 80.4 | 74.3 | 70.5 |

| Public services (e.g., water supply and sanitation) | 75.6 | 81.2 | 76.7 |

| Residential services (e.g., household management, property management) | 74.9 | 76.6 | 74.6 |

| Construction industry | 77.5 | 74.3 | 71.1 |

| Transportation, warehousing, and post industry | 75.5 | 68.5 | 65.7 |

| Education | 74.6 | 70.7 | 67.0 |

| Farming, forestry, husbandry, and fishing | 76.0 | 73.8 | 72.1 |

| Wholesale and retail | 79.1 | 76.0 | 72.8 |

| Gas supply industry | 68.6 | 62.2 | 62.2 |

| News, cultural medium, and entertainment industry | 74.0 | 73.6 | 70.0 |

| Information transmission, software, and information technology services | 73.7 | 73.2 | 63.6 |

| Medical and healthcare service | 77.9 | 75.1 | 71.0 |

| Public management (i.e., governments, subdistrict offices) | 78.7 | 81.0 | 77.5 |

| Manufacturing industry | 78.4 | 73.7 | 71.2 |

| Accommodation and catering services | 80.9 | 72.9 | 69.7 |

| NGOs and social organizations | 75.4 | 75.0 | 68.7 |

| Others | 76.4 | 73.0 | 69.9 |

| TOTAL | 76.5 | 73.0 | 69.5 |

| The Attitude of Guangzhou Residents toward: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| People from Other Provinces | People from Other Countries | Favorability of Living in Guangzhou | |

| Real estate industry | 73.4 | 76.6 | 77.2 |

| Public services (e.g., water supply and sanitation) | 64.0 | 72.0 | 76.0 |

| Residential services (e.g., household management, property management) | 72.9 | 77.1 | 77.1 |

| Construction industry | 74.0 | 78.3 | 72.8 |

| Transportation, warehousing, and post industry | 68.2 | 74.2 | 71.0 |

| Education | 67.1 | 73.3 | 72.3 |

| Farming, forestry, husbandry, and fishing | 76.8 | 83.9 | 76.8 |

| Wholesale and retail | 76.7 | 79.2 | 78.5 |

| Gas supply industry | 64.1 | 72.4 | 72.4 |

| News, cultural medium, and entertainment industry | 74.8 | 77.7 | 77.0 |

| Information transmission, software, and information technology services | 75.7 | 76.2 | 73.5 |

| Medical and healthcare service | 69.8 | 76.3 | 72.8 |

| Public management (i.e., governments, subdistrict offices) | 77.0 | 81.1 | 77.0 |

| Manufacturing industry | 76.5 | 80.8 | 78.0 |

| Accommodation and catering services | 69.3 | 73.2 | 72.9 |

| NGOs and social organizations | 76.3 | 82.1 | 77.9 |

| Others | 71.5 | 74.9 | 74.3 |

| TOTAL | 70.6 | 75.7 | 73.3 |

| The Attitude of Guangzhou Residents toward: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| People from Other Provinces | People from Other Countries | Favorability of Living in Guangzhou | |

| Real estate industry | 40.0 | 40.0 | 100.0 |

| Construction Industry | 60.0 | 60.0 | 50.0 |

| Transportation, warehousing, and post industry | 55.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 |

| Gas supply industry | 100.0 | 100.0 | 80.0 |

| News, cultural medium, and entertainment industry | 80.0 | 80.0 | 100.0 |

| Medical and healthcare service | 60.0 | 80.0 | 60.0 |

| Manufacturing industry | 80.0 | 100.0 | 60.0 |

| Accommodation and catering services | 80.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 |

| TOTAL | 65.0 | 75.0 | 73.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, C.; Zhan, M.; An, X.; Huang, X. Social Inclusion Concerning Migrants in Guangzhou City and the Spatial Differentiation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315548

Zhou C, Zhan M, An X, Huang X. Social Inclusion Concerning Migrants in Guangzhou City and the Spatial Differentiation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315548

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Changchang, Meixu Zhan, Xun An, and Xu Huang. 2022. "Social Inclusion Concerning Migrants in Guangzhou City and the Spatial Differentiation" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315548

APA StyleZhou, C., Zhan, M., An, X., & Huang, X. (2022). Social Inclusion Concerning Migrants in Guangzhou City and the Spatial Differentiation. Sustainability, 14(23), 15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315548