Abstract

This paper develops the multiple-theoretical framework of legitimacy, stakeholders, and voluntary perspective to assess the adoption of Vietnamese listed firms to the 17 United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The paper’s primary objective is to use content analysis to discover the status quo of the SDGs practices of the largest 100 Vietnamese listed firms on the two biggest Vietnamese stock exchanges (Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange–HOSE and Hanoi Stock Exchange–HNX). By drawing a unique framework, the paper contributes to the extant literature review of SDG-related research. Our research framework enables corporate decision-makers significantly access corporate SDG adoptions and the implementation process. With the direct pressure of stakeholders, high environmental sensitivity industries are keen on disclosing SDG-related information. Notwithstanding, the findings reveal that Vietnamese listed firms indicate “green talks” in their corporate reporting rather than “green actions”. Thus, our findings encourage firms to engage in SDGs through substantive sustainability strategies and need greater attention from governments, practitioners, and policymakers.

1. Introduction

To address sustainable development priorities, 193 nations met and signed on to the SDGs at the United Nations in New York in September 2015 [1]. These goals are established by a global partnership of governments, civil society, the private sector, and others to drive the world’s transition toward the goals’ achievements [2]. The plan for Sustainable Development includes 17 goals and 169 targets which set out a plan for all nations’ sustainable development to achieve by 2030, as seen in Table 1. These 17 UN SDGs reflect the “state of the art” thinking of governments worldwide [3].

Vietnam joined the United Nations on 20 September 1977 to receive support for war reconstruction and humanitarian assistance [4]. In May 2017, Vietnam released its National Action Plan (NAP) to show the effort of the Government to implement the Vietnam SDGs (VN SDGs). It was promulgated as per Decision 633/QD-TTg dated 10 May 2017 of the Prime Minister, in which the global goals of Vietnam towards 2030 were set, including 115 specific targets, as presented in Table 2 [5]. For example, the following three extracts illustrate companies’ initiatives to achieve SDGs:

FPT Corporation (FPT) provided a general statement regarding SDGs awareness in their recent Annual Reports:

“The Sustainable Development Goals call for global actions towards a sustainable future for all countries by 2030. As a leading technology corporation in Vietnam, FPT is ready to play its role in all 17 of these millennium goals.”[6]

While TNG Investment and Trading JSC (TNG) stated that:

“Aiming at sustainable development on all of the economic, social, and environmental aspects, TNG has developed and obtained some achievements in 2021, associated with the specific objectives of TNG as well as 17 UN sustainable development goals for the period of 2015–2030.”[7]

Similarly, Viet Nam Dairy Products Joint Stock Company (VNM) highlighted that:

“Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to poverty, climate change, and food and nutritional security is a major challenge, given the significant impacts of climate change on all aspects of life. From now to 2030, there are only 12 years left to speed up. This requires urgent actions by countries along with cooperative partnerships between governments and stakeholders at all levels.”[8]

These quotes indicated that Vietnam companies had attempted to adopt and follow the 17 UN SDGs. However, it is not easy to incorporate the business model with SDGs, especially for companies in developing countries [9]. Besides, Pizzi et al. [10] and Silva [11] pinpointed that companies have struggled to reconcile their financial performance with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices, including SDG disclosures. That is why although SDGs are in their infant stages of implementation, there is an increasing number of studies examining different perspectives of SDGs toward sustainable corporate development to interpret the role of SDGs in sustainability reporting [12].Nevertheless, several studies indicated that the relationship between SDGs and corporate reporting has barely been examined [13,14,15].

Regarding research methodologies, it is undeniable that content analysis is the most appropriate method to examine the extent and quality of corporate reporting [11,16,17,18]. However, in terms of theoretical framework, prior literature has applied a single theory to explain corporate engagement toward SDGs, such as legitimacy theory [19]; stakeholder theory [20,21]. Within one single theory, more is needed to discover the level of corporate engagement in SDGs and corporate reporting of sustainability-related information. This is because the 17 UN SDGs are considered a collection of 17 interlinked global goals striving for the prosperity of the CSR pillars (social, environmental, and governance), not focusing on a particular topic in corporate sustainability performance. Moreover, referring to the corporate reporting of SDGs, it is inexplicable to ignore “corporate motivation” in committing to voluntary disclosure. It is also important to investigate whether this engagement and adoption of SDGs are symbolic (i.e., green talk) or substantive (i.e., green action) [16,17]? So, there is a need to develop a multi-theoretical framework to explore the SDG disclosure levels in corporate sustainability reports [13,15,18]—especially in developing countries such as Vietnam.

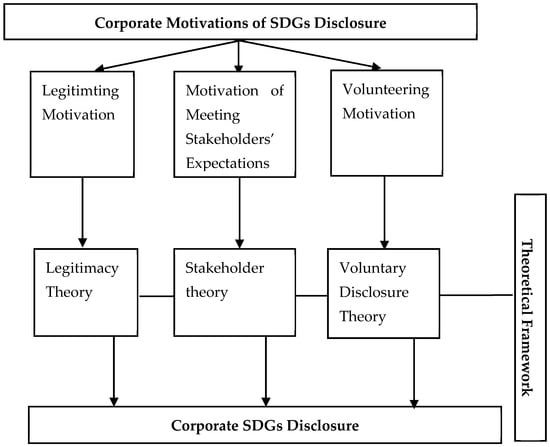

Therefore, in line with several recently published research, such as Silva [11]; Van der Waal & Thijssens [16]; Emma & Jennifer [17]; Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. [18], and Ike et al. [13], the authors developed a multi-theoretical motivated framework for SDGs adoption, including legitimacy theory (legitimating motivation), stakeholder theory (motivation of meeting stakeholders’ expectations) and voluntary disclosure theory (volunteering motivation) to bridge the literature gap by answering the following main research questions: (1) What is the current state of SDG disclosures among Vietnamese firms? (2) How do Vietnamese listed firms disseminate SDGs in their reports? (3) How do Vietnamese listed companies adopt a symbolic/substantive strategy in disclosing SDGs information? (4) Which SDGs are addressed mainly by listed Vietnamese firms, and which industries focus more on achieving these SDGs?

To answer these research questions, this paper employs the content analysis method to 893 corporate reports of the top100 firms listed on the two main Vietnamese Stock Exchanges, including the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HOSE) and the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX). Particularly, the sample consists of 692 annual reports in Vietnamese, 177 annual reports, and 24 standalone sustainability reports from 2015 to 2021. Based on the market capitalization, we selected 50 firms from HOSE and 50 from HNX with the highest market capitalization as they are most likely to disclose sustainability-related information, including SDGs. Based on Helfaya & Whittington [22], the search sample contains thirteen industries categorized into three industrial dimensions: high environmental sensitive industries (HESI), medium environmental sensitive industries (MESI), and low environmental sensitive industries (LESI), as seen in Table 4. For consistency, all reports of the Top 100 listed firms were downloaded from a reliable website (Vietstock) and corporate websites.

Our findings indicate that 84% of total firms are partly engaging with the 17 SDGs (only focusing on some specific goals), particularly SDG1—Poverty, SDG8—Economic growth, and SDG13—Climate change. This suggests that there is a lack of “actual implementation” or substantive performance to achieve the global goals among Vietnamese listed firms. Additionally, firms operating in HESI intend to have green talks in their reporting statements rather than green actions to achieve these SDGs. Interestingly, supported by our multi-theoretical framework of legitimacy, stakeholders, and voluntary disclosure theories, we found that many companies in HESI tend to avoid disclosing SDG-related information to protect their legitimacy and avoid legal commitment and public discontent.

Consequently, within our unique multi-theoretical framework, our study can fully cover various aspects of SDGs and the “motivation” to achieve them. Accordingly, this research can be considered pioneering research on the adoption and implementation of the UN SDGs in the Vietnamese context with two highlights. Firstly, relying on our research findings, it is undoubtedly that SDGs have gained a great attention among Vietnamese listed firms. However, it is still challenging due to a need for consistent reporting mechanisms and substantive strategies related to their implementation plans as part of their business operating objectives. For that reason, our findings are crucial and can be used as a guideline for corporate decision-makers of Vietnamese listed firms to satisfy their stakeholders’ expectations. Secondly, our results are essential for the Vietnamese government, regulators, and policymakers to track the progress of Vietnamese listed firms toward SDG adoption and implementation, enabling them to better support companies in adopting and achieving these goals and fulfilling the UN Agenda of 2030 at the country level.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the literature review. Section 3 describes research methodologies, including research sample, data collection, and research method. Section 4 discusses the research results, and Section 5 concludes the study.

Table 1.

The Measurement of 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Table 1.

The Measurement of 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

| Goals | Measurement | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SDG1 | No Poverty | End poverty in all its forms everywhere |

| SDG2 | Zero Hunger | End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture |

| SDG3 | Good Health and Well-being | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages |

| SDG4 | Quality Education | Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all |

| SDG5 | Gender Equality | Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls |

| SDG6 | Clean Water and Sanitation | Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all |

| SDG7 | Affordable and Clean Energy | Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all |

| SDG8 | Decent Work and Economic Growth | Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all |

| SDG9 | Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation |

| SDG10 | Reduce Inequality | Reduce inequality within and among countries |

| SDG11 | Sustainable Cities and Communities | Make cities and human settlement inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable |

| SDG12 | Responsible Consumption and Production | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| SDG13 | Climate Action | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts |

| SDG14 | Life Below Water | Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development |

| SDG15 | Life on Land | Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reserve land degradation and halt biodiversity loss |

| SDG16 | Peace and Justice Strong Institution | Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels |

| SDG17 | Partnership to Achieve the Goal | Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development |

Table 2.

The 17 UN SDGs and VN SDGs.

Table 2.

The 17 UN SDGs and VN SDGs.

| Sustainable Development Goals | Components | Targets | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN SDGs | VN SDGs | UN SDGs | VN SDGs | |

| Goal 1. No Poverty | End poverty in all its forms everywhere | Similar | 7 (1.1–1.5; 1.a–1.b) | 4 (1.1–1.4) |

| Goal 2. Zero Hunger | End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture | Similar | 8 (2.1–2.5; 2.a–2.c) | 5 (2.1–2.5) |

| Goal 3. Good Health and Well-being | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | Ensure a healthy life and enhance welfare for all citizens in all age groups | 13 (3.1–3.9; 3.a–3.d) | 9 (3.1–3.9) |

| Goal 4. Quality Education | Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all | Similar | 10 (4.1–4.7; 4.a–4.c) | 8 (4.1–4.8) |

| Goal 5. Gender Equality | Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls | Achieve gender equality; empower and create enabling opportunities for women and girls | 9 (5.1–5.6; 5.a–5.c) | 8 (5.1–5.8) |

| Goal 6. Clean Water and Sanitation | Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all | Similar | 8 (6.1–6.6; 6.a–6.b) | 6 (6.1–6.6) |

| Goal 7. Affordable and Clean Energy | Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all | Similar | 5 (7.1–7.3; 7.a–7.b) | 4 (7.1–7.4) |

| Goal 8. Decent Work and Economic Growth | Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all | Similar | 12 (8.1–8.10; 8.a–8.b) | 10 (8.1–8.10) |

| Goal 9. Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation | Develop a highly resilient infrastructure; promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization; and promote renovation | 8 (9.1–9.5; 9.a–9.c) | 5 (9.1–9.5) |

| Goal 10. Reduce Inequality | Reduce inequality within and among countries | Reduce social inequalities | 10 (10.1–10.7; 10.a–10.c) | 6 (10.1–10.6) |

| Goal 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities | Make cities and human settlement inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable | Promote sustainable, resilient urban and rural development; ensure safe living and working environments; ensure a reasonable distribution of population and workforce by region | 10 (11.1–11.7; 11.a–11.c) | 10 (11.1–11.10) |

| Goal 12. Responsible Consumption and Production | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns | Similar | 11 (12.1–12.8; 12.a–12.c) | 9 (12.1–12.9) |

| Goal 13. Climate Action | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts | Respond in a timely and effective manner to climate change and natural disasters | 5 (13.1–13.3; 13.a–13.b) | 3 (13.1–13.3) |

| Goal 14. Life Below Water | Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development | Similar | 10 (14.1–14.7; 14.a–14.c) | 6 (14.1–14.6) |

| Goal 15. Life on Land | Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reserve land degradation and halt biodiversity loss | Sustainably protect and develop forests; conserve biodiversity; develop eco-system services; combat desertification; prevent the degradation of and rehabilitate soil resources | 12 (15.1–15.9; 15.a–15.c) | 8 (15.1–15.8) |

| Goal 16. Peace and Justice Strong Institution | Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels | Similar | 12 (16.1–16.10; 16.a–16.b) | 9 (16.1–16.9) |

| Goal 17. Partnership to Achieve the Goal | Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development | Similar | 19 (17.1–17.19) | 5 (17.1–17.5) |

| Total | 17 | 10/17 VN SDGs are entirely similar to SDGs. | 169 | 115 |

2. Literature Review

2.1. 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Before the SDGs officially came into force, the aim started as an idea of sustainable goals by the Norwegian Prime Minister to define the sustainable development as: “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [23]. After several conferences/roundtable meetings of the 30-member UN General Assembly Open Working Group on SDGs (such as Rio+20; the 68th session of the General Assembly), the Post-2015 Development Agenda was finally processed since the Open Working Group (OWG) submitted their proposal with 8 SDGs and 169 targets, called “The Eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)” [24]. Officially, the SDGs were set up in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly.

All countries, regardless of their wealth, are called to promote prosperity while protecting the planet, tackling climate change, and addressing social challenges [25]. These SDGs are critically linked and underpin each other. For example, SDG1—No poverty and SDG2—Zero hunger, meaning that if any country can achieve either SDG1 or SDG2, their citizens must have the capability to strive for better well-being (SDG3) or quality education (SDG4). According to the United Nations, at the macro-level (i.e., country level), countries should take the primary responsibility to follow up and review the progress made in implementing SDGs [26]. At the micro-level (i.e., firm-level), firms are expected to apply their innovations, creativity, and financial resources to achieve the SDGs, which would effectively address the three sustainability dimensions: economic, environmental, and social [2].

The implementation of 17 UN SDGs by countries is now firmly in place. According to Sustainable Development Report 2022 within 163 countries by Sachs [27], the world progressed on the SDG Index at an average rate of 0.5 points a year from 2015 to 2019, which is considered too slow to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Simultaneously, the progress of SDGs implementation varied significantly across countries and goals. Sachs [27] found that poorer countries with lower SDG Index scores progressed faster than more affluent countries. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, global energy, and financial crises, SDG Index scores have declined slightly since early 2020.

Accordingly, SDG1—No poverty and SDG2—Zero hunger were highly affected. For example, over 140 million people could fall into extreme poverty (measured against the $1.90 poverty line) in 2020 [28]. Additionally, countries heavily depend on the international trade system, and tourism would face a challenge to achieving SDG8—Decent work and economic growth. For instance, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand, and New Zealand have been seriously affected by the COVID-19 pandemic—notably, a declining figure of around 110 arrivals for every additional person infected by the coronavirus [29]. In contrast to the pandemic’s negative effect, Finland, Denmark, and Sweden, are the top 3 countries that effectively adopted and achieved the SDGs as stated in the SDG Index and Dashboards, respectively [27].

2.2. Adoption and Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by Vietnam

The Vietnamese Prime Minister’s office approved the National Actional Plan to implement the Global Agenda 2030 for sustainable development (SD). The Plan was categorised into six intervention dimensions [30], including:

- Guiding the development of legal frameworks and policies on sustainable consumption and production.

- Promoting sustainable production.

- Greening the supply system.

- Promoting the sustainable export market.

- Changing consumption practices and supporting sustainable lifestyles.

- Advancing 3R (reduce, reuse, recycle) practices.

Table 2 proves that the Vietnamese National Action Plan (NAP) has been implemented in the correct direction. Regarding the global level, according to the Sustainable Development Report 2015, Vietnam has not been engaged in SDGs, except for some Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, such as Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. By 2016, Vietnam started to commit to the 17 UN SDGs; however, the ranking was much below the average, at the 88th. Since 2017, the ranking of Vietnam on the index has considerably improved, thanks to the implementation of NAP. For example, Vietnam was one of 163 countries assessed in the 2022 SDG Index. Vietnam was ranked in 55th place with an overall index score of 72.8 [27], the same score as in 2022 (as presented in Table 3). Yet, its ranking was the 51st, which suggests that the average score among all nations has increased. Since 2015, East and South Asia have progressed more on the SDGs than any other region adopting sustainable goals. Among Southeast Asia, Vietnam has been ranked the 2nd country with the highest score on the SDG Index, just below Thailand for both years 2021 and 2022.

Table 3.

Vietnam’s Score on the SDG Index and Dashboard.

Besides Vietnam’s National Action Plan on Sustainable Consumption and Production (2021–2030), the Vietnamese Government has implemented several activities, such as various conferences, to ensure the country is on the right track for SDGs implementation. For example, the Conference “National Assembly of Vietnam and the Sustainable Development Goals” was organized by the National Assembly of Vietnam, the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), and the United Nations in Vietnam in December 2018. The conference covered different SDG topics (e.g., gender equality, decent work and economic growth, peace, and justice) [31].

Although the Vietnamese Government has actively promoted the SDGs by developing a legal framework [32], there are limited tools to assess the adoption of SDGs at the micro-level, such as the corporate level. It is challenging to examine the process of adopting the SDGs for a particular firm operating across the sectors, even for listed firms on the stock exchange.

2.3. Theoretical Background and Research Questions

The critics of the first definition of SD by Brundtland’s Commission have opened a road for hundreds of alternative definitions from scholars and practitioners [33]. For example, one of the popular definitions of SD is defined by the National Strategy of Sustainable Development (2003): “Sustainable development is the society’s development that creates the possibility for achieving overall wellbeing for the present and the future generations through combining environmental, economic, and social aims of the society without exceeding the allowable limits of the effect on the environment” [34]. Within the widespread SD phenomenon, SDGs is defined as “a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future” [35]. Due to limited resources available on Earth (e.g., water) [36], the SDG framework guides human beings to strive for SD in the long run [37].

Regarding firm-level of SDG adoption, SDGs enable firms to select and prioritize corporate sustainability issues and align strategies toward specific and relevant CSR pillars [38]. Since its launch in 2015, many firms around the world have started to disclose the SDGs or SDGs-related information in their annual report (AR), standalone sustainability report (SR), or integrated report (IR) to declare their committed effort to SD [39,40,41]. At the same time, literature on sustainability reporting started shifting towards corporate engagement in the SDGs. There are several topics have been examined, such as the potential role of corporate activities in supporting the SDGs [42,43], the factors that affect companies’ engagement in sustainable practices [18,44,45], and the firms’ motivation or opportunities toward achieving the SDGs [46]. However, the studies by Ike et al. [13]; Diaz-Sarachaga [15], and Bennich et al. [14] indicate that the correlation between the SDGs and corporate sustainability reporting has barely been investigated.

Among limited empirical studies on the exploration of SDG disclosure levels in corporate sustainability reporting, Yu et al. [47] assessed the adoption and implementation of corporate SDG disclosure by analyzing the content in the corporate reporting of 100 Chinese companies listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange from 2016 to 2018. They found that Chinese companies primarily focused on specific SDGs (such as SDG9—Industry, innovation, and infrastructure development; SDG8—Decent work and economic growth and SDG16—Peace and justice strong institution). Noticeably, their findings reveal that most companies focused solely on presenting SDG disclosure information rather than genuinely performing sustainable actions to achieve these goals. In the same vein, Manes-Rossi & Nicolo’ [48] conducted a content analysis of the non-financial reports to analyze how SDGs reporting is evolving and what are the most addressed SDGs in the context of the European energy sector companies. They pointed out that the disclosure of SDGs is an indispensable part of corporate reporting, yet more symbolic than substantial changes appear. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct an in-depth analysis to assess the corporate SDG disclosures and how the SDGs information is disclosed in the sustainability-related report.

SDGs have been critically emphasized from the introduction until now. However, scholars have highlighted that not all SDGs are mentioned in corporate reporting [48], suggesting that there is a particular focus on those SDGs [47]. Several potential reasons behind this concentration of SDG disclosure by firms have been figured out. For example, Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. and Diaz-Sarachaga [15,18] found that focusing on specific SDGs makes it easier to incorporate SDGs into corporate practices (e.g., Goal 8—Decent work and economic growth, Goals 12—Responsible consumption and production, and 13—Climate action). In contrast, because of the focus of certain SDGs by firms, some goals with more macroeconomic impacts (e.g., Goal 1—No poverty, Goals 2—Zero hunger, and 17—Partnership) are less mentioned [39,49]. Simultaneously, Van der Waal & Thijssens [16] found that some companies are not motivated to engage in SDGs, which are weakly linked to their core business activities.

As for emerging markets with weak overall legal systems and strong shareholder protection [50], a question arises by Van der Waal & Thijssens [16]: Why should listed firms voluntarily engage with SDGs while being principally shareholder value-oriented? Let us take an example, Sekarlangit & Wardhani [51] analyzed the impact of the board of directors’ characteristics and the existence of CSR committees on SDG disclosures in corporate reporting for five Southeast Asian countries—Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Philippines. They found that CSR committees can encourage more intensive SDG disclosures. Simultaneously, the finding reveals that the higher commitment to the sustainability agenda, the higher level of SDG disclosures [38]. Interestingly, Scheyvens et al. [2] argued that the SDGs are the nation-states’ agreements rather than individuals’ or businesses’ actions. Besides, CSR is tightly linked to success when implementing global goals by world countries [52]. Similarly, Van der Waal & Thijssens [16] mapped the undiscovered terrain of corporate SDG involvement from the sustainability reports of the largest 2000 stock-listed businesses worldwide. They found that corporate SDG involvement is still limited (23% of the total sample of 2000 firms), and listed companies voluntarily engage in SDGs if it creates value for the common good. Additionally, Khaled et al. [53] developed a critical framework by hand-mapping the SDGs and their targets with a firm’s sustainability practices. They found that the SDGs relate to their ESG performance and tangibly measure their progress towards achieving the SDGs. Consequently, we claim that SDG disclosures strongly relate to firms’ industry sectors and the awareness of SD and CSR practices.

At the industry level, according to Van der Waal & Thijssens; Heras-Saizarbitoria et al.; Diaz-Sarachaga and Manes-Rossi & Nicolo’ [15,16,18,48], there is a lack of studies to explore how the SDGs are prioritized across different industries. Al-Tuwaijri et al. and Young et al. [54,55] claimed that the quality of sustainability reporting is dependable on the industry risk characteristics. They found that sustainability reporting is more robust in high-risk compared to low-risk industries. Indeed, firms operating in environmentally sensitive sectors (e.g., energy, tourism, or chemicals) intend to have high awareness and interest in the commitment and achievement of SDGs [39,44,49]. In contrast, Nechita et al. [44] evaluated the disclosure of SDG information in corporate reports using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. They found that 63% of the analyzed reports did not mention the SDGs. Surprisingly, the presentation of the SDG information in their selected sample was not similar even in the same industry.

Critically implementing SDGs into business models is necessary [11,56]. Emma et al. [17] argued that despite the high engagement of European companies in symbolic disclosures, SDGs reporting still plays a substantive role among companies operating in controversial and environmentally sensitive industries. They claimed that firms had employed SDGs as “a symbolic legitimacy approach” to address or enhance legitimacy issues and respond to the expectation of stakeholders. This finding is consistent with the studies of Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. [18] and Silva [11]. They vehemently claimed that firms would instead show their compliance with stakeholders’ pressures to gain legitimacy than implement actual corporate actions to commit to SDGs.

Nevertheless, empirical studies revealed that most firms follow a symbolic approach toward SDG disclosures rather than providing substantive SDG reporting [16]. For instance, Izzo et al. [49] rationalized that the requirements of the SDGs and specific KPIs or achievement of SDGs are still missing in corporate reporting. As a result, we believe that businesses should use SDG disclosure as “a strategic tool” to achieve business ethics and sustainable responsibility, instead of using it as a symbolic strategy to “deal” with stakeholders’ pressure of non-financial disclosure, such as SDGs.

Therefore, the need to explore SDG disclosure levels in corporate sustainability reporting [13,15,18] and the current debate on the dichotomy of symbolic/substantive approach to SDG disclosures [16,17] calls for more in-depth empirical evidence in different industries. Simultaneously, the literature review evidenced that while there is an increasing appetite for demonstrating a corporate commitment to SDGs, limited research indicates how companies effectively integrate SDGs in their reporting practices in developing countries. As a result, following the calls for filling this research gap, this research developed a multi-theoretical framework, including a legitimacy perspective–legitimacy theory; a stakeholder expectation–stakeholder theory, and a voluntary approach–voluntary disclosure theory of digging deep into ARs/SRs published by Top 100 Vietnamese Listed Firms in both HOSE) and HNX through a longitudinal and cross-sectorial approach. In doing so, our research paper intends to answer the following research questions:

- RQ1: What is the current state of SDG disclosures among Vietnamese firms?

- RQ2: How do Vietnamese listed firms disseminate SDGs in their reports?

- RQ3: How do Vietnamese listed companies adopt a symbolic/substantive strategy in disclosing SDGs information?

- RQ4: Which SDGs are addressed by listed Vietnamese firms, and which industries focus more on achieving these SDGs?

Since most previous empirical studies on SDG-related topics draw on legitimacy theory [11,19,57,58,59], Calabrese et al. [38] indicated that there is a need for frameworks to fully understand how companies are engaging in achieving the SDGs. Thus, to answer the above research questions and provide a practical framework that assists companies in incorporating SDGs information into their non-financial reporting.

Firstly, in corporate social reporting, Guthrie et al. [60] pointed out that legitimacy theory posits that CSR disclosures are reactions to environmental factors to legitimize corporate actions. Additionally, O’Donovan [58] claimed that legitimacy theory posits that the survival and success of corporations correspond with society’s expectations, suggesting that firms are required to act and perform in “socially acceptable behaviors” manner. Deegan [61] undertook a study examining the social and environmental disclosures of BHP Ltd. to ascertain the corporate social and environmental disclosures and pinpointed that legitimacy theory refers to a “social contract” between the corporate and the society in which they operate or “community license to operate”. According to legitimacy theory, the corporate SDG disclosure is presented in the corporate reporting to show companies’ efforts in achieving SDGs and conforming to the community’s desire for non-financial information or managing the firms’ legitimacy [11,57,62]. Additionally, legitimacy theory indicates that poorly sustainability-performing firms use sustainability disclosure as a legitimation tool to lead the community perceptions [63]. Therefore, under legitimacy theory, we assume that corporate SDG disclosure has been used as “a strategic tactic” to strengthen the firm legitimacy or even to alter society’s expectation because of the managers’ perceptions, which strongly influences the business model of a specific firm.

Regarding stakeholders’ perspectives, stakeholder engagement is essential for implementing CSR strategies and achieving SDGs [45,64,65]. Stakeholder theory can be used to explain how corporations engage in SDG disclosures. Mainly, this theory posits that “managing for stakeholders” involves paying attention to the interests and well-being of primary stakeholders (including employees and managers, shareholders, financiers, customers, and suppliers) [66]. Therefore, instead of using symbolic strategies to disclose SDGs in sustainability reports, several firms have chosen to link SDGs to their stakeholders’ expectations and then communicate their CSR strategy to the public. For example, Lopez [67] analyzed Spanish MNCs’ (CSR) strategy and how they incorporate the SDGs into their reporting systems. The results revealed that firms communicated their operating performance in economic, social, and environmental aspects by linking SDGs’ targets to various primary stakeholders of the corporation.

Although sustainability reporting is commonly used to describe the self-reporting of CSR-related activities [68], it is still optional in most countries [69]. Therefore, voluntary disclosure theory also offers another theoretical explanation for corporate SDG disclosures [70]. Initially, this theory was derived from game theory, meaning that a corporation’s motivation in making or withholding disclosures depends upon shareholders’ value [71]. In response to voluntary disclosure theory, Nishitani et al. [68] found a positive relationship between sustainability performance and its reporting. They claimed that companies are motivated to use sustainability-related reporting to aid improved decision-making by their shareholders. Furthermore, to address the stakeholders’ expectations, companies voluntarily engage in and account for sustainability-related issues in their reporting systems [72,73,74].

Therefore, we claim that firms intend to mention SDG disclosures in their reporting in a voluntary basis; they use it as “a communication tool” to satisfy primary stakeholders’ transparent demand for non-financial information to increase legitimacy or even manage the stakeholders’ perception (regardless of the impact of industrial sectors). Figure 1 shows the research framework developed from a multi-theoretical foundation of legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory, and voluntary disclosure theory.

Figure 1.

Research Theoretical Framework.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Sample and Data Collection

Our initial sample consists of the top 100 firms listed on the two biggest Vietnamese Stock Exchanges, Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HOSE) and Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX) from 2015 to 2021. Based on the market capitalization, we selected the top 50 firms from both HOSE and HNX. Vietnam is an emerging market, and therefore SDG disclosures or sustainability reporting is still optional. From the legitimacy perspective, big companies are more likely to incorporate the SDGs into their reporting systems than small ones [19] to gain a positive public image and reputation [22,57,75,76]. Therefore, we chose these firms with a strong belief that they have integrated the SDGs information into their corporate reporting. Simultaneously, within the big 100 firms, they can firmly represent the Vietnamese economic trend in disclosing SDGs-related information.

In sum, our sample includes 13 industrial sectors including accommodation and food services; agriculture production; construction and real estate; finance and insurance; food & beverage; health care; information and technology; manufacturing; mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction; natural gas distribution; transportation and warehousing; utilities; and wholesale trade in which the construction and real estate sector account represents 32% of total firms. All reports of the 100 selected firms were downloaded from corporate websites and Vietstock (for further details of the website, please access via this link: https://en.vietstock.vn/ (accessed on 27 August 2022)). 96 Vietnamese firms have integrated sustainability reports (SRs) in their annual reports (ARs) as a separate section to disclose CSR or sustainability matters. Only four firms published their standalone SRs between 2015 and 2021, namely BVH, SSI, VCS, and VNM.

In line with our research objectives and prior literature review [13,15,16,17,18], this research analyzed the sample of 893 firm-year observations of Vietnamese ARs and SRs of the big 100 listed firms in HOSE and HNX for the period 2015–2021. Additionally, we relied on previous CSR disclosure literature to understand how different industries focus most on achieving these SDGs [22,70,77]. Notably, we categorized 13 industries into 3 groups based on their levels of environmental sensitivity: 8 high environmental sensitivity industries (HESI: accommodation and food services; agriculture production; construction and real estate; food & beverage; manufacturing; mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction; natural gas distribution and utilities) with 67 companies; 4 medium environmental sensitivity industries (MESI: health care; information and technology; transportation and warehousing and wholesale trade) with 8 companies, and 1 low environmental sensitivity industry (LESI: finance and insurance) with 25 companies, as seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample Selection and Industry Composition.

3.2. Research Method: Content Analysis

Krippendorff [78] discovered the method of “content analysis”, which is a “research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from data according to their context” [22,79]. This method has become “the most common method of analyzing the textual fabric of contemporary society” [78]. This method enables researchers to place and codify the text of narrative writing into different items/subjects based on selected criteria [22,57,79]. For SDG-related topics, many researchers have applied content analysis to AR and SR [18,38,41,48,62], as this method is considered an excellent instrument to measure relative levels and trends in reporting [60,80]. Therefore, relying on content analysis, this research examined 893 reports, including information of corporate SDG disclosures for the period between 2015 and 2021, to address the proposed research questions. Each firm was considered a unit of analysis.

Following Schreier [81], we organized our data collection based on a systematic multi-process of three stages, including:

- Stage 1: Extraction and collection of SDGs information from the reports with the selection of illustrative quotations.

- Stage 2: Development of the categorization framework.

- Stage 3: Analysis and interpretation of data.

At first, we extracted the selected reports using available tools. Many searches were made using different keywords related to the term “Sustainable Development Goals” (such as “Sustainable Development Goals”, “SDGs”, “Goals”, “CSR”, “Sustainability”, “Aim”, “Objective”, etc.). All reports have been downloaded from both Vietstock and corporate websites. At this stage, we made an overview of the reports by identifying the main sections containing the information on the SDGs and generating the first insight into how companies present their adoption and achievement of the SDGs. The recording units of analysis cover specific linguistic information such as words, sentences, and lines, and consider both narrative and non-narrative disclosure (such as graphs, tables, figures, and pictures) [82]. At the same time, the illustrative quotation was selected for the English version of 177 ARs by choosing the statement, discussion, or images of corporate SDGs information, the corporate SDGs implementation processes, the corporate CSR-related activities (e.g., prevent climate change, save energy, protect the environment, do charitable works, protect human and labor rights, etc.).

Next, we developed the coding framework to capture the corporate disclosure of SDGs. The disclosure checklist including 17 UN SDGs was developed by Silva [11] and used to quantify the current state of SDG disclosures among Vietnamese-selected firms. Specifically, we reviewed every report to check how many times each of these 17 UN SDGs was disclosed/reported by the selected firms. Simultaneously, we generated a checklist of SDGs’ engagement by the 13 industrial sectors to highlight the SDGs concentration toward sectors. After that, we appraised the most recent reports of the sample by using three main criteria to assess how Vietnamese listed firms incorporate SDGs in their reports and examine whether these firms adopt a symbolic or substantive strategy in disclosing SDG information, such as (1) Any mention of SDGs in CEO and/or Chair’s message; (2) Any indication of potential risks and opportunities related to the SDGs; and (3) Any association of specific key performance indicators (KPI) to priority SDGs.

For the last stage, as in other works carrying out this type of analysis [18,41], the information obtained from the reports was then analyzed and interpreted.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Assessment of Vietnamese SDGs Adopters: Current Status of SDG Disclosures

Firstly, Table 5 records the descriptive statistical results of the adoption of the 17 UN SDGs of the selected sample. It suggests a notable difference in implementing SDGs among Vietnamese firms. For example, SDG1—Poverty and SDG8—Economy have been received great attention from Vietnamese firms (with a mean of 0.69 and 1.12, respectively). Therefore, it can be argued that firms operating in developing countries intend to incorporate the goal of solving poverty and contributing to economic growth rather than making a significant effort to focus on various aspects of SDGs, like climate change. Since the transition to a low-carbon economy is already underway [83]; thus, our finding outlines that there is a need for companies in the developing world to act seriously on fighting climate change.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 6 reports the results of our mapping between selected firms and their engagement with the 17 UN SDGs and the descriptive statistics of disclosing SDGs from 2015 to 2021. Additionally, Table 6 presents the ranking of 100 firms according to the number of disclosing the 17 UN SDGs in their reports. For example, the 17 UN SDGs-related information mentioned in corporate reporting ranges from 0 (e.g., QCG; CTX; NDN; S99; POM; TKU; KLF and PVI) to 22 times (e.g., VIC), meaning that firms are inconsistent in following the SDG Disclosures. In other words, some firms have shown a “real” effort more than others, and even though some firms lack efforts in adopting the SDGs. Therefore, this highlights that firms have different perspectives to adopt SDGs.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics by Firms.

Our mapping (as seen in Table 6) shows that firms do not follow all 17 UN SDGs. Only 8% of the selected firms reported sustainability information about these 17 SDGs for seven years (2015–2021), which suggests that some goals should be focused on by the States rather than corporations [53]. Firms also need to adopt “macro” goals, such as SDG10—Reduce inequality and SDG11—Sustainable cities and communities, since it is emphasized that “Organizations must acknowledge their impact on the achievement of sustainable development both outside and within the organization’s boundary” [84].

Likewise, it is indicated that there are three main patterns of Vietnamese firms’ SDGs adoptions (as presented in Table 6), including “unfollow, partly follow, and fully follow.” In more detail, for cases of ignoring the terms “Sustainable Development Goals” in their corporate reporting, we point out that there are two primary reasons. The first reason is because of the reporting format. Although no SDGs information is mentioned for some firms, they still disclose SDG-related information on their corporate websites. The second reason is that their business models are not focused on the SDGs, which is in line with previous studies [44,47]. Indeed, even in the same industries, the reporting of the SDGs information of the selected sample was different.

Our findings show that 84% of total firms are just partly engaging in the 17 SDGs (i.e., focusing only on some specific goals) across various sectors (e.g., poverty, economic growth, and climate change). This suggests a lack of “actual implementation” of SDGs among Vietnamese firms. Regarding the CSR session in the AR, there is a question: Do these firms “pretend” to satisfy the stakeholders’ expectations of social and environmental information or honestly act to progress their commitment toward the SDGs? This can be proved by matching these specific and focused goals by Vietnamese companies with the 3 pillars of CSR practices, such as SDG1—Poverty/Social; SDG8—Decent working environment and economic growth/Governance; SDG13—Climate change/Environment) [53,85].

A review of both ARs and SRs indicated that companies intend to primarily focus on improving poverty, economic growth, and climate change, as illustrated in the following quotations:

“Applications of the circular economy will help reduce the cost of business operation, increase competitiveness and lead to global development opportunities worth up to USD 4.5 trillion by 2030.”[8]

“Continuing the annual charity program of giving Tet gifts to the poor conducted from 2009, BIDV gave away 30,000 sets of Tet gifts, with the value of VND15 billion, together with local authorities to take care of the poor, helped the poor to have a warm Tet whenever spring comes.”[86]

“On August 5, 2021, KIDO Group donated 1532 bottles of cooking oil equivalent to VND 582,000,000 for the program “Emergency support for disadvantaged people in Ho Chi Minh City.”[87]

“In an effort to help people overcome the damages, at the end of October, PDR’s mission visited and donated gifts to people in the most affected communes of Quang Ninh and Le Thuy districts. The total value of donations by Phat Dat was VND 500 million.”[88]

“Continue to promote strengths, take more domestic market share which is aiming to the objective of 70–80% drilling market share in Vietnam; expand market share of drilling service and drilling related services in regional and global markets, create added value for clients by high quality services and competitive prices.”[89]

“…Gemadept has taken concrete steps both in decisions and actions to work towards the goal of responding to climate change, joining hands with the Vietnam Government in sustainable development, reflected in green and environmentally friendly port projects, shifting to renewable energy, reforestation projects.”[90]

Notably, 8% of the sampled firms were fully committed to SDGs (namely, STB, VNM, VCS, PDR, NTP, BVH, TNG, and PVD), and aware of the importance of sustainable development. Thus, our theoretical framework can explain these patterns of SDGs implementation among industries in an emerging market like Vietnam, particularly:

- Unfollow: firms lack all three motivations: legitimating motivation, motivation to meet stakeholders’ expectations, and volunteering motivation;

- Partly follow: firms indicate one/two motivation(s) toward adopting and achieving SDGs adoptions; or

- Follow: firms indicate their great motivation to achieve sustainable development.

4.2. Assessment of Vietnamese SDGs Adopters: Evaluation of Environmental Sensitive Industries Impact Level

This analysis of the SDG disclosures of the Top 100 Vietnamese listed firms reveals a general trend toward the content of Vietnamese corporate reports across the sectors. Table 7 presents our mapping between industries categorized by the level of sensitive environmental factors and the adoption of 17 UN SDGs from 2015 to 2021. Overall, there is an increasing trend in the number of SDGs disclosed in the corporate reporting, for example, HESI: 291 to 585 times; MESI: 20 to 41 times; LESI: 87 to 163 times. Unsurprisingly, Panel A—High environmental sensitivity industries (HESI) accounts for the highest number of mentions regarding SDGs in the selected firms’ corporate reporting compared to Panel B and Panel C year by year. This result is consistent with previous research findings [54,55], meaning that SDG-related information disclosed by corporations primarily depends on industry risk characteristics. However, with firms operating in the Low environmental sensitivity industries (LESI), Panel C revealed more SDG-related information in their reports compared to Panel B, with firms operating in the Medium environmental sensitivity industries (MESI). This result is consistent with the predictions derived from stakeholder theory that high-risk industries disclose more sustainability information to meet the stakeholders’ expectations of enhancing CSR practices.

Table 7.

Adoption of SDGs by Environmental Sensitive Industries Impact Level.

Next, as presented in Table 8, sectors are deeply interpreted as the level of adopting the 17 UN SDGs. Although Table 7 reveals that firms belonging to high environmental sensitivity industries have an impact on the way of reporting the SDGs information. Some HESI firms have not made a solid effort to follow the SDGs agenda. For instance, two HESI sectors: natural gas distribution and utilities, have weakly followed and committed to the UN SDGs, apart from SDG8 Decent Work and Economic Growth; suggesting that even operating in high-risk industries, the level of adoption is different from sector to another because of the business core model rather than capturing “the trend” to adopt the SDGs implementation in their reporting practice. Interestingly, our result indicates that LESI firms are intensely keen to disseminate their sustainability initiatives in their corporate reporting, despite the absence of stakeholders’ pressure related to firms’ legitimacy and transparency motivations. This finding is consistent with previous studies by [82,91], as they have no product-related risks to hide. These findings can be explained by legitimacy theory and voluntary disclosure theory; unsustainable performers intend to disclose less sustainability-related information to conceal their actual performance for sustainable development and avoid damaging their legitimacy and reputation.

Table 8.

Adoption of SDGs by Sectors.

4.3. Assessment of Vietnamese SDGs Adopters: Substantive or Symbolic Approaches to Corporate Legitimacy

Table 9 describes how firms disclose information about their SDGs in their corporate reporting, whether it is substantive (green-wishing) or symbolic (greenwashing), by reviewing all selected firms’ reports with three main criteria (1) The awareness of the CEO/chairman toward SDGs; (2) The corporate awareness of risks and opportunities related to SDGs and (3) The corporate-specific KPIs associated with the SDGs. Table 9 is also used to indicate the trends of firms in committing to SDGs by comparing the answers “Yes” and “No” for two preceding years: 2015 (the year of global implementation of SDGs) and 2021 (the current year). Surprisingly, there is considerable inconsistency in adopting and disclosing SDGs information by the Top 100 Vietnamese firms. For instance, some firms have SDG-related information in the CEO/chairman. Yet, there is no information indicating the risks/opportunities or connection between their firms’ KPIs to the SDGs, suggesting that managers’ perception of SDGs is insignificant to disclose SDG information. Moreover, some firms (e.g., OCH, HAG, and KDH) show their effort in committing to the SDGs by indicating this fact in the CEO/Chairman letter in 2015. However, no information was mentioned in 2021. Accordingly, our findings suggest Vietnamese firms show a “green talk” not a “green action” in their ARs or standalone SRs rather than following substantive SDG strategies.

Table 9.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Disclosures Criteria Check List.

Additionally, several companies attempt to indicate their effort to engage in SDGs without specific KPIs, as shown in the below quotes:

“BIDV has always tried to ensure equity environment and paid attention to material and spiritual lives of female staff, as well as created conditions for female staff to participate in professional operation, promotion and appointment (mostly at department leader positions)”[92]

“Construction and operation of real estate projects consume a large amount of energy. Therefore, to save energy, Khang Dien actively applies many solutions to save power and fuel.”[93]

“Baoviet always engages economic growth with environmental protection and social responsibility—three pillars on which a long-term success of Baoviet is built...”[94]

“...BVSC always encourages and mobilizes employees to use public transport, helping to reduce CO2 into the environment.”[95]

Notwithstanding, 8% of total firms (as presented in Table 6) indicate that they wish to be green (green wishing) by indicating an effort to adopt all global goals. Furthermore, although during 2015–2021, some firms just partly followed the 17 UN SDGs, these firms have set and achieved specific key performance indicators (KPI).

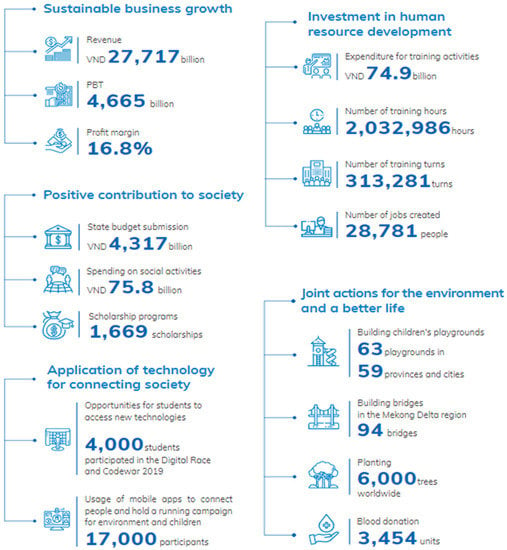

For example, as seen in Figure 2, FPT sets some objectives to ensure the achievement of sustainable growth [96].

Figure 2.

FPT Corporation’s KPI for SDGs.

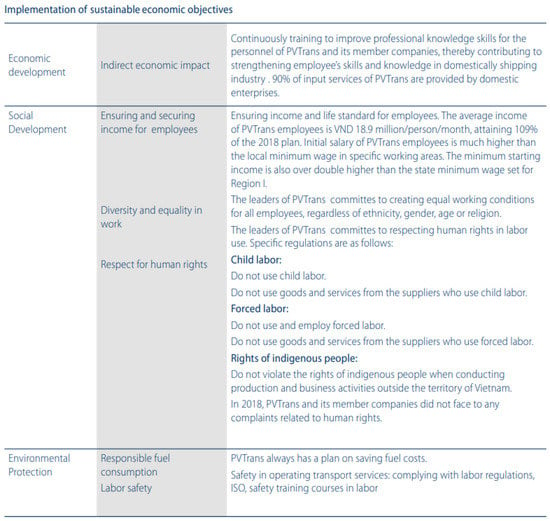

Besides, Petrovietnam Transportation Corporation (PVT) indicated their SDG targets, as presented in Figure 3 which was extracted from the AR 2018 [97].

Figure 3.

Petrovietnam Transportation Corporation’s KPI for SDGs.

Additionally, for 2015, 21% of the sampled firms mentioned the SDGs in the CEO/Chairman letter, 15% showed their awareness of risks related to SDGs, and 41% linked their KPIs to SDGs. Compared to 2021, there is an increasing trend; however, there is a neglectable increase for the three criteria, 20%, 26%, and 56%, respectively. Although many firms link their business objectives to SDGs, as pointed out in Table 5 and Table 6, these SDGs primarily indicate the firms’ effort to legitimize the firms’ images of sustainable development rather than achieving the UN SDGs. Additionally, our findings show a lack of corporate understanding of SDG risks and opportunities among the top 100 Vietnamese firms. Therefore, our results suggest that it is necessary for Vietnamese firms to significantly use SDG disclosures as ‘a strategic tool’ or green wishing/substantive actions to strengthen their legitimate image for striving for long-term SDGs. Instead of using it as greenwashing actions to “deal” with stakeholders’ pressure of non-financial disclosures such as SDGs, which is in line with previous literature [16,17,49].

5. Conclusions

Throughout the analysis of the top 100 Vietnamese listed firms on the two biggest stock exchanges (HOSE and HNX), we provide a holistic picture of how firms operating in emerging markets like Vietnam adopt and follow the 17 UN SDGs. As pioneering research in the context of Vietnam, we reviewed the corporate reporting of SDGs in both ARs and SRs. Our findings indicate that 84% of total firms are partly engaging in the 17 UN SDGs, by focusing on some specific goals (SDG1—Poverty, SDG8—Economic growth, and SDG13—Climate change). This suggests that there is a lack of “actual implementation” for SDGs among Vietnamese listed firms.

At the industry level, we found that corporate SDG disclosures differ between corporations because of their business strategies rather than the nature of their industrial sectors. Furthermore, the findings indicate that firms operating in high environmental sensitivity industries are keen on reporting SDG-related information compared to medium and low environmental sensitivity industries. Unsurprisingly, many companies operating in high-risk industries (e.g., natural gas distribution and utilities) avoid disclosing SDG-related information to protect their legitimacy. Likewise, our findings reveal a considerable inconsistency in adopting and disclosing the SDG information to the public, suggesting that Vietnamese firms should use SDG disclosure as ‘a strategic tool’ to strengthen their legitimacy and truly satisfy stakeholders’ social, environmental, and business ethic expectations.

Consequently, from a theoretical standpoint, this research can contribute to the academic literature on adopting and disclosing SDGs in developing countries. It represents one of the first studies to explore SDG adoption in a developing country’s context by providing a unique multi-theoretical framework of legitimacy, stakeholders, and voluntary disclosure theories to analyze the motivation for adopting the 17 UN SDGs.

From a practical perspective, our findings can be used as a guideline for corporate decision-makers of Vietnamese publicly traded firms to identify the status of SDGs adoption and implementation and satisfy stakeholders’ expectations. The findings also send a warning message to the board of directors/corporate decision-makers to adopt and embed the 17 UN SDGs into their business models and organizational culture. Simultaneously, this research also contributes to exploring the corporate adoption and implementation efforts to report SDGs toward fulfilling the UN Agenda of 2030 for developing countries. At the country level, our findings are essential for government, practitioners, and policymakers to support companies in adopting and achieving these UN SDGs as part of their business strategies and objectives by providing a consistent and binding framework for communicating the action plan and achievement level of these SDGs in ARs and/or standalone SRs.

Like other research, this paper has some limitations, yet it provides vital opportunities for future research. Firstly, the research sample only focuses on Vietnamese listed firms on the two biggest stock exchanges. Therefore, the discovery of the SDGs’ adoption and implementation may only partially reflect the holistic view of all Vietnamese companies. Moreover, our findings point out a question mark for the case of adopting the 17 UN SDGs in a developing country, Vietnam (Do these firms “pretend” to satisfy the stakeholders’ expectations of social and environmental information or honestly act to progress their commitment toward the SDGs?). Therefore, future research may consider a large sample size (e.g., by using cross-country corporate data) or adopt qualitative research methods using questionnaires and/or semi-structured interviews to assess the impact of managers’ religious beliefs, personal characteristics, and attitudes towards corporate sustainable development in different countries adopted and implemented the 17 UN SDGs, see, for example, Helfaya & Easa [98]. Secondly, since this is the case of Vietnam, the results should be applied with caution in different contexts. Consequently, at a micro level, future research can consider adopting our research framework for multi-national companies operating in different industries to investigate the key determinants (e.g., firm’s characteristics and corporate governance factors) that affect the process of adopting and implementing these 17 SDGs. At a macro level, future research could examine the institutional factors (e.g., legal systems, ownership structure, size of capital markets, cultural factors, political stability, environmental regulations, etc.) in both developing and developed countries to discover what aspects of emerging countries are different from other developed countries; and to examine the difference among countries in implementing and engaging SDGs. Thirdly, we primarily relied on content analysis to investigate the status quo of adopting and implementing the 17 UN SDGs in Vietnam. Accordingly, future research could employ a mixed methodology (e.g., quantitative and qualitative) to investigate the level of adopting and implementing the 17 UN SDGs and their determinants.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed equally to this research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the journal’s academic editor, Ioannis Nikolaou, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. The authors also acknowledge financial research support from Becamex Business School, Eastern International University, Vietnam. All remaining errors are our own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mio, C.; Panfilo, S.; Blundo, B. Sustainable Development Goals and the Strategic Role of Business: A Systematic Literature Review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3220–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The Private Sector and the SDGs: The Need to Move Beyond ‘Business as Usual. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An Enabling Role for Accounting Research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSDG|UN in Action—Viet Nam. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- The National Action Plan for the Implementation of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: https://vietnam.un.org/index.php/en/4123-national-action-plan-implementation-2030-sustainable-development-agenda (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- FPT Corporation Annual Report 2021. Available online: https://bctn2021.fpt.com.vn/en (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- TNG Investment and Trading JSC Annual Report 2021. Available online: https://tng.vn/userfiles/files/Quan%20H%E1%BA%B9%20c%E1%BB%95%20%C4%91%C3%B4ng/BAO%20Cao%20Thuong%20Nien%202021/20220429_TNG_AR2021_EN.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Viet Nam Dairy Products Joint Stock Company Annual Report 2018. Available online: https://www.vinamilk.com.vn/static/uploads/bc_thuong_nien/1553157661-ea4e37fe1db29419325178dd843588da6e8234bb730198a6aa961d741128712e.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Lauwo, S.G.; Azure, J.D.-C.; Hopper, T. Accountability and Governance in Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals in a Developing Country Context: Evidence from Tanzania. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 1431–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Caputo, A.; Corvino, A.; Venturelli, A. Management Research and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Bibliometric Investigation and Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. Corporate Contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals: An Empirical Analysis Informed by Legitimacy Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, M.F.; dello Strologo, A.; Granà, F. Learning from the Best: New Challenges and Trends in IR Reporters’ Disclosure and the Role of SDGs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, M.; Donovan, J.D.; Topple, C.; Masli, E.K. The Process of Selecting and Prioritising Corporate Sustainability Issues: Insights for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennich, T.; Weitz, N.; Carlsen, H. Deciphering the Scientific Literature on SDG Interactions: A Review and Reading Guide. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M. Shortcomings in Reporting Contributions towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waal, J.W.H.; Thijssens, T. Corporate Involvement in Sustainable Development Goals: Exploring the Territory. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, G.-M.; Jennifer, M.-F. Is SDG Reporting Substantial or Symbolic? An Examination of Controversial and Environmentally Sensitive Industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Urbieta, L.; Boiral, O. Organizations’ Engagement with Sustainable Development Goals: From cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, A.; Weber, O.; Geobey, S. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats? Global Reporting Implications in a Post SDGs World. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2021, 22, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Business Contribution to the Sustainable Development Agenda: Organizational Factors Related to Early Adoption of SDG Reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayikci, Y.; Kazancoglu, Y.; Gozacan-Chase, N.; Lafci, C. Analyzing the Drivers of Smart Sustainable Circular Supply Chain for Sustainable Development Goals through Stakeholder Theory. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3335–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Whittington, M. Does Designing Environmental Sustainability Disclosure Quality Measures Make a Difference? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future—Call for Action. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahida, D.P.; Sendhil, R.; Ramasundaram, P. Millennium to the Sustainable Development Goals: Changes and Pathways for India. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2021, 4, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgason, K.S. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Recharging Multilateral Cooperation for the Post-2015 Era. Glob. Policy 2016, 7, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, Å.; Weitz, N.; Nilsson, M. Follow-up and Review of the Sustainable Development Goals: Alignment vs. Internalization. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2016, 25, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Lafortune, G.; Kroll, C.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2022. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2022/2022-sustainable-development-report.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Swinnen, J.; McDermott, J. COVID-19 and Global Food Security. Available online: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll2/id/133762 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Tran, B.-L.; Chen, C.-C.; Tseng, W.-C.; Liao, S.-Y. Tourism under the Early Phase of COVID-19 in Four APEC Economies: An Estimation with Special Focus on SARS Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengesbaugh, M.; Olsen, S.; Zusman, E. Governing National Sustainable Consumption and Production Action Plans in the Philippines and Viet Nam: A Comparative Analysis; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Hayama, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Conference on National Assembly and Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://vietnam.un.org/vi/node/8939 (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Nishitani, K.; Nguyen, T.B.H.; Trinh, T.Q.; Wu, Q.; Kokubu, K. Are Corporate Environmental Activities to Meet Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Simply Greenwashing? An Empirical Study of Environmental Management Control Systems in Vietnamese Companies from the Stakeholder Management Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowy, I. Defining Sustainable Development for Our Common Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781135961220. [Google Scholar]

- Ciegis, R.; Ramanauskiene, J.; Martinkus, B. The Concept of Sustainable Development and Its Use for Sustainability Scenarios. Eng. Econ. 2009, 2, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rusciano, V.; Civero, G.; Scarpato, D. Social and Ecological High Influential Factors in Community Gardens Innovation: An Empirical Survey in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Kusaka, H.; Bornstein, R.; Ching, J.; Grimmond, C.S.B.; Grossman-Clarke, S.; Loridan, T.; Manning, K.W.; Martilli, A.; Miao, S.; et al. The Integrated WRF/Urban Modelling System: Development, Evaluation, and Applications to Urban Environmental Problems. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable Development Goals for People and Planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Gastaldi, M.; Levialdi Ghiron, N.; Villazon Montalvan, R.A. Implications for Sustainable Development Goals: A Framework to Assess Company Disclosure in Sustainability Reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtó-Pagès, F.; Ortega-Rivera, E.; Castellón-Durán, M.; Jané-Llopis, E. Coming in from the Cold: A Longitudinal Analysis of SDG Reporting Practices by Spanish Listed Companies Since the Approval of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Szekely, M. Disclosure on the Sustainable Development Goals—Evidence from Europe. Account. Eur. 2022, 19, 152–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lawati, H.; Hussainey, K. Does Sustainable Development Goals Disclosure Affect Corporate Financial Performance? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.S. The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Are a Great Gift to Business! Procedia CIRP 2018, 69, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kücükgül, E.; Cerin, P.; Liu, Y. Enhancing the Value of Corporate Sustainability: An Approach for Aligning Multiple SDGs Guides on Reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechita, E.; Manea, C.L.; Nichita, E.-M.; Irimescu, A.-M.; Manea, D. Is Financial Information Influencing the Reporting on SDGs? Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Chemical Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, F.; Iaia, L.; Mehmood, A.; Vrontis, D. Can Social Media Improve Stakeholder Engagement and Communication of Sustainable Development Goals? A Cross-Country Analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 177, 121525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebestová, J.; Sroka, W. Sustainable Development Goals and SMEs Decisions: Czech Republic vs. Poland. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. JEECAR 2020, 7, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Sial, M.S.; Tran, D.K.; Badulescu, A.; Thu, P.A.; Sehleanu, M. Adoption and Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in China—Agenda 2030. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolo’, G. Exploring Sustainable Development Goals Reporting Practices: From Symbolic to Substantive Approaches—Evidence from the Energy Sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1799–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, M.F.; Ciaburri, M.; Tiscini, R. The Challenge of Sustainable Development Goal Reporting: The First Evidence from Italian Listed Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L.F.; Love, I. Corporate Governance, Investor Protection, and Performance in Emerging Markets. J. Corp. Financ. 2004, 10, 703–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekarlangit, L.D.; Wardhani, R. The Effect of the Characteristics and Activities of the Board of Directors on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Disclosures: Empirical Evidence from Southeast Asia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Lin, W.; He, Y.; Streimikis, J. Policies to Promote Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Assessment of CSR Impacts. Bus. Adm. Manag. 2019, 22, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R.; Ali, H.; Mohamed, E.K.A. The Sustainable Development Goals and Corporate Sustainability Performance: Mapping, Extent and Determinants. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tuwaijri, S.A.; Christensen, T.E.; Hughes, K.E. The Relations among Environmental Disclosure, Environmental Performance, and Economic Performance: A Simultaneous Equations Approach. Account. Organ. Soc. 2004, 29, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Marais, M. A Multi-Level Perspective of CSR Reporting: The Implications of National Institutions and Industry Risk Characteristics. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2012, 20, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, J.D. Sustainable Development Goals and Progressive Business Models for Economic Transformation. Local Econ. J. Local Econ. Policy Unit 2019, 34, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Moussa, T. Do Board’s Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy and Orientation Influence Environmental Sustainability Disclosure? UK Evidence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, G. Environmental Disclosures in the Annual Report. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 344–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; van Staden, C.J. Can Less Environmental Disclosure Have a Legitimising Effect? Evidence from Africa. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Parker, L.D. Corporate Social Reporting: A Rebuttal of Legitimacy Theory. Account. Bus. Res. 1989, 19, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The Legitimising Effect of Social and Environmental Disclosures—A Theoretical Foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, T.; Kotb, A.; Helfaya, A. An Empirical Investigation of U.K. Environmental Targets Disclosure: The Role of Environmental Governance and Performance. Eur. Account. Rev. 2022, 31, 937–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Rankin, M.; Tobin, J. An Examination of the Corporate Social and Environmental Disclosures of BHP from 1983–1997. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 312–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo-Alhama, C.; Igual-Antón, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies in Spanish Electric Cooperatives. Analysis of Stakeholder Engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.; Kim, M. From Stakeholder Communication to Engagement for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Case Study of LG Electronics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Bosse, D.A.; Phillips, R.A. Managing for Stakeholders, Stakeholder Utility Functions, and Competitive Advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, B. Connecting Business and Sustainable Development Goals in Spain. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, K.; Unerman, J.; Kokubu, K. Motivations for Voluntary Corporate Adoption of Integrated Reporting: A Novel Context for Comparing Voluntary Disclosure and Legitimacy Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 322, 129027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, I. The Mandatory Social and Environmental Reporting: Evidence from France. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 229, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the Relation between Environmental Performance and Environmental Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, R.A. An Evaluation of “Essays on Disclosure” and the Disclosure Literature in Accounting. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 32, 181–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.-M.; Gallego-Alvarez, I.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. Stakeholder Engagement and Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: The Ownership Structure Effect. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Ooi, S.K.; Mydin, R.T.; Devi, S.S. The Impact of Business Strategies on Online Sustainability Disclosures. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Klassen, R.D.; Vachon, S.; Kalchschmidt, M. Sustainable Evaluation and Verification in Supply Chains: Aligning and Leveraging Accountability to Stakeholders. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Capitalism and Freedom; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]