What Skills Do Addiction-Specific School-Based Life Skills Programs Promote? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. Life Skills Programmes

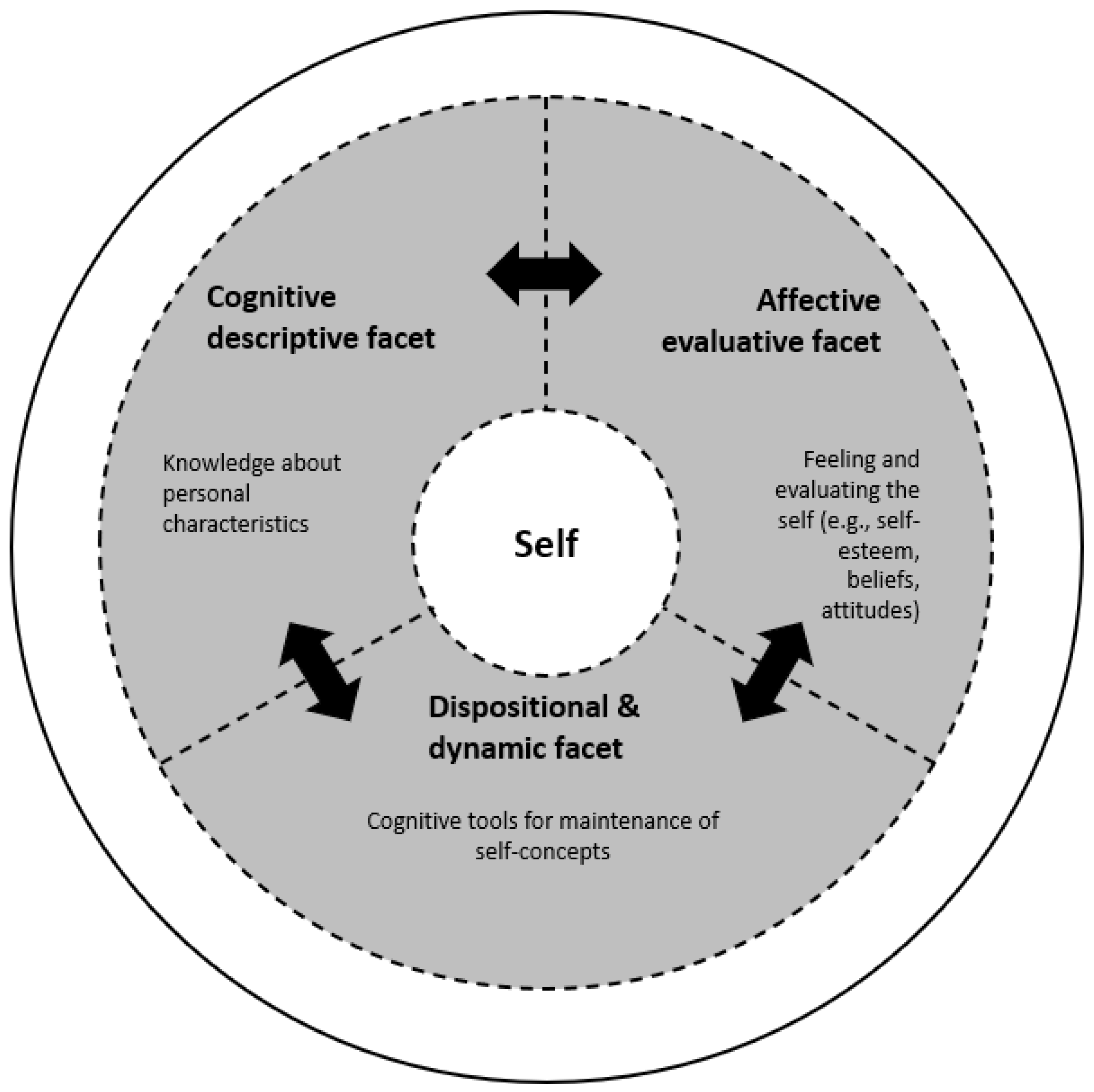

1.2. The Promotion of Life Skills Influences the Self

1.3. Efficacy of LSPs and Research Gap

2. Methods

2.1. Criteria for Considering Studies for this Review

2.1.1. Types of Participants

2.1.2. Types of Interventions

2.1.3. Types of Studies

2.1.4. Types of Control

2.1.5. Types of Outcome Measures

2.2. Search Methods for Identification of Studies

2.2.1. Electronic Searches

2.2.2. Searching Other Resources

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

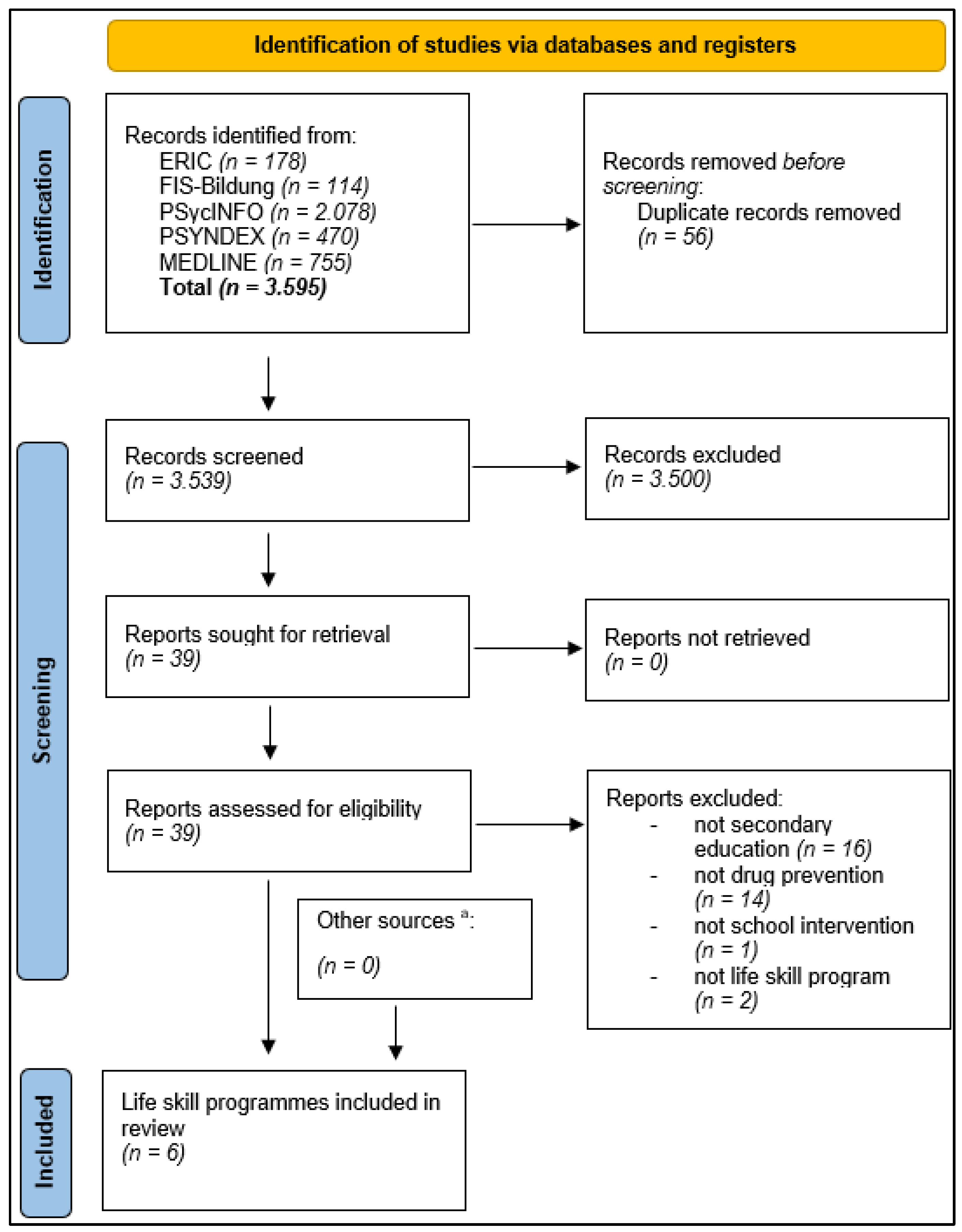

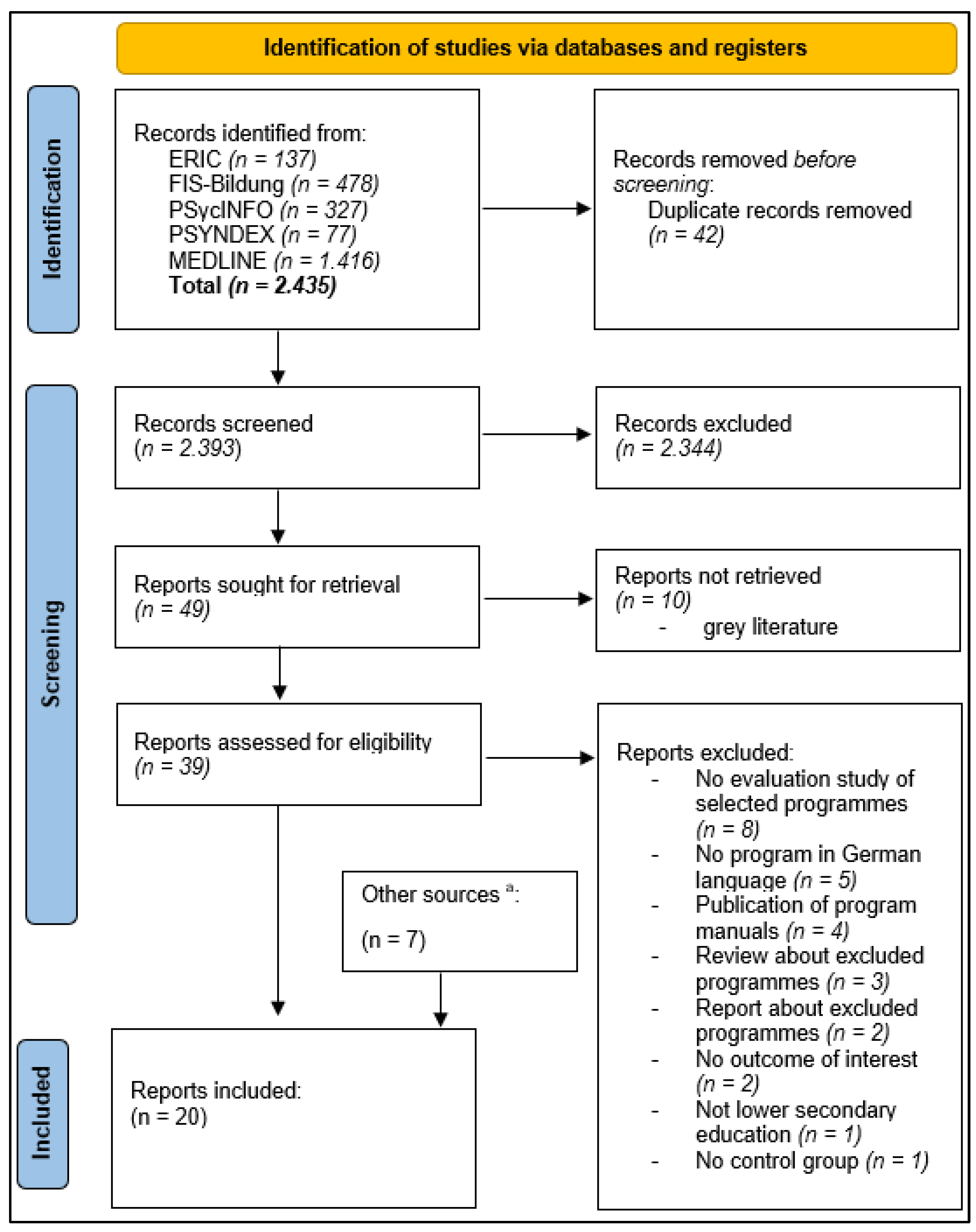

2.3.1. Selection of Life Interventions for Addiction Prevention

2.3.2. Selection of Studies

2.3.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

2.5. Measures of Treatment Effect

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Search

3.2. Description of the Selected School-Based LSPs

3.3. Included Studies and Their Implementation

3.4. Setting and Study Participants

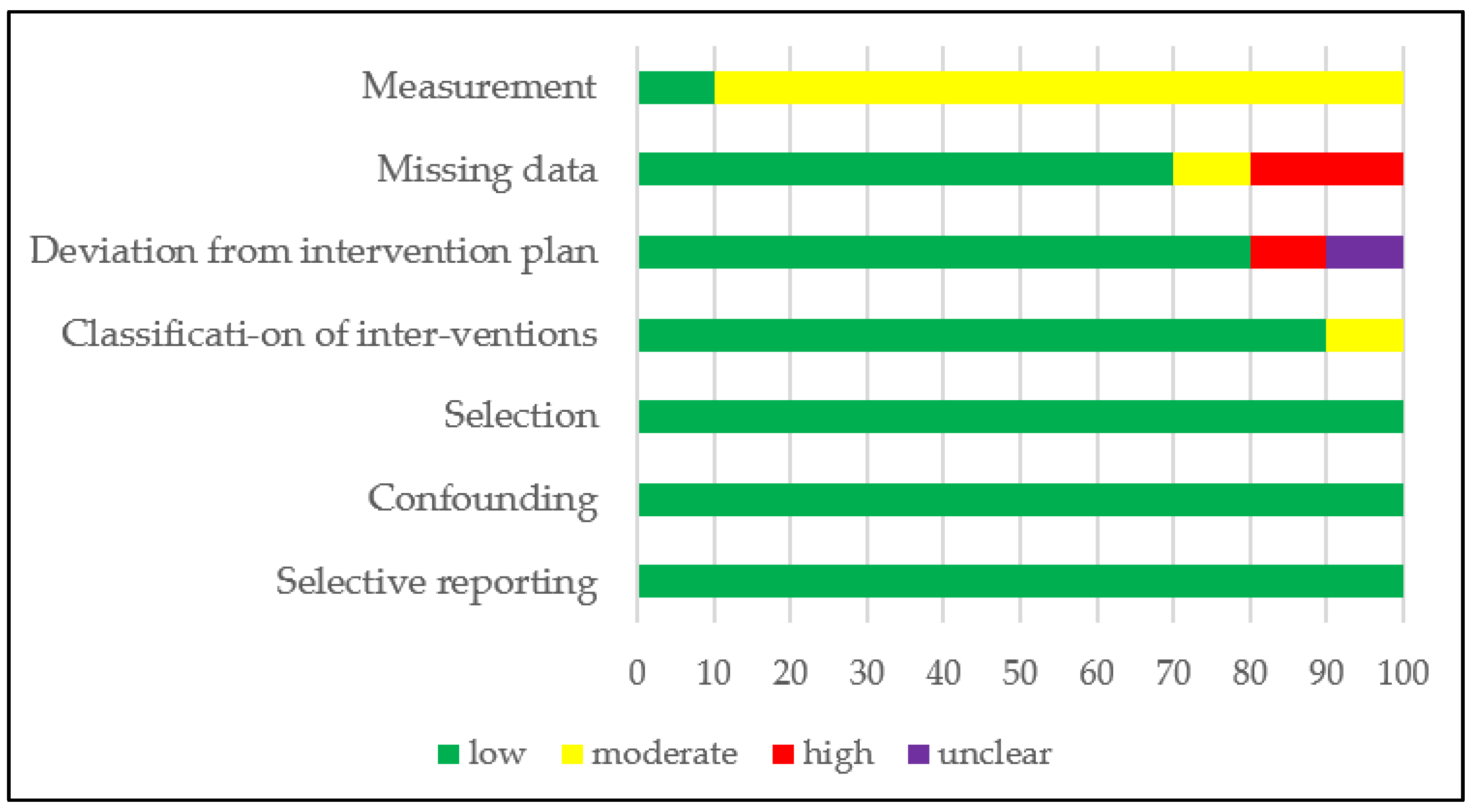

3.5. Risk of Bias in Included Studies

3.5.1. Measurement

3.5.2. Missing Data

3.5.3. Deviation from Intervention Plan and Bias in Classification of Interventions

3.6. Summary of the Evidence

3.6.1. Which Life Skills Are Evaluated?

3.6.2. Effects in the Individual Evaluations

3.6.3. Effects of Individual LSPs

4. Discussion

- Six comparable addiction prevention LSPs and ten associated program evaluations with 20 reports have been identified according to the inclusion criteria.

- The LSPs show similar content but differ in their temporal scope between 600 min (Unplugged) and 3150 min (L-Q). The intervention duration in the individual evaluation studies varies between four months (F&S 1), six months (IPSY 1 & 3 and Unplugged) and a whole school year (ALF, F&S 2, L-Q and Rebound). In one case, a three-day block course has been conducted (IPSY 2).

- The study quality of the evaluation studies has been assessed as good using the ROBINS-I tool. Individual exceptions have been noted in the measurement of outcomes, assignment to intervention and control groups, and adherence to the intervention plan. Evaluations of F&S, Rebound and Unplugged are of higher risk of bias than the evaluations of ALF, IPSY and L-Q.

- The evaluation studies prove to be heterogeneous in terms of school type, regional location, gender distribution, and the measurement instruments used.

- Interpersonal life skills have not been evaluated.

- Individual aspects of intrapersonal life skills have been examined with various instruments, although no instrument used could be directly assigned to a life skill.

- The promotion of intrapersonal life skills has been studied to varying degrees in the individual program evaluations. The differences include, for example, the number of instruments and measurements performed. Looking at the number of instruments used, the following ranking emerges: ALF (n = 14), IPSY (n = 13), R & S (n = 5), L-Q (n = 5), Rebound (n = 3), and UNPLUGED (n = 0). Furthermore, there is methodological heterogeneity in terms of follow-up periods, which vary from six months (F&S 2, L-Q) to 48 months (IPSY 1). In two evaluations (F&S 1, Rebound), only one pretest and one posttest have been performed.

- Due to the lack of life skills measurements in the evaluation of the Unplugged program, it is not reported on further.

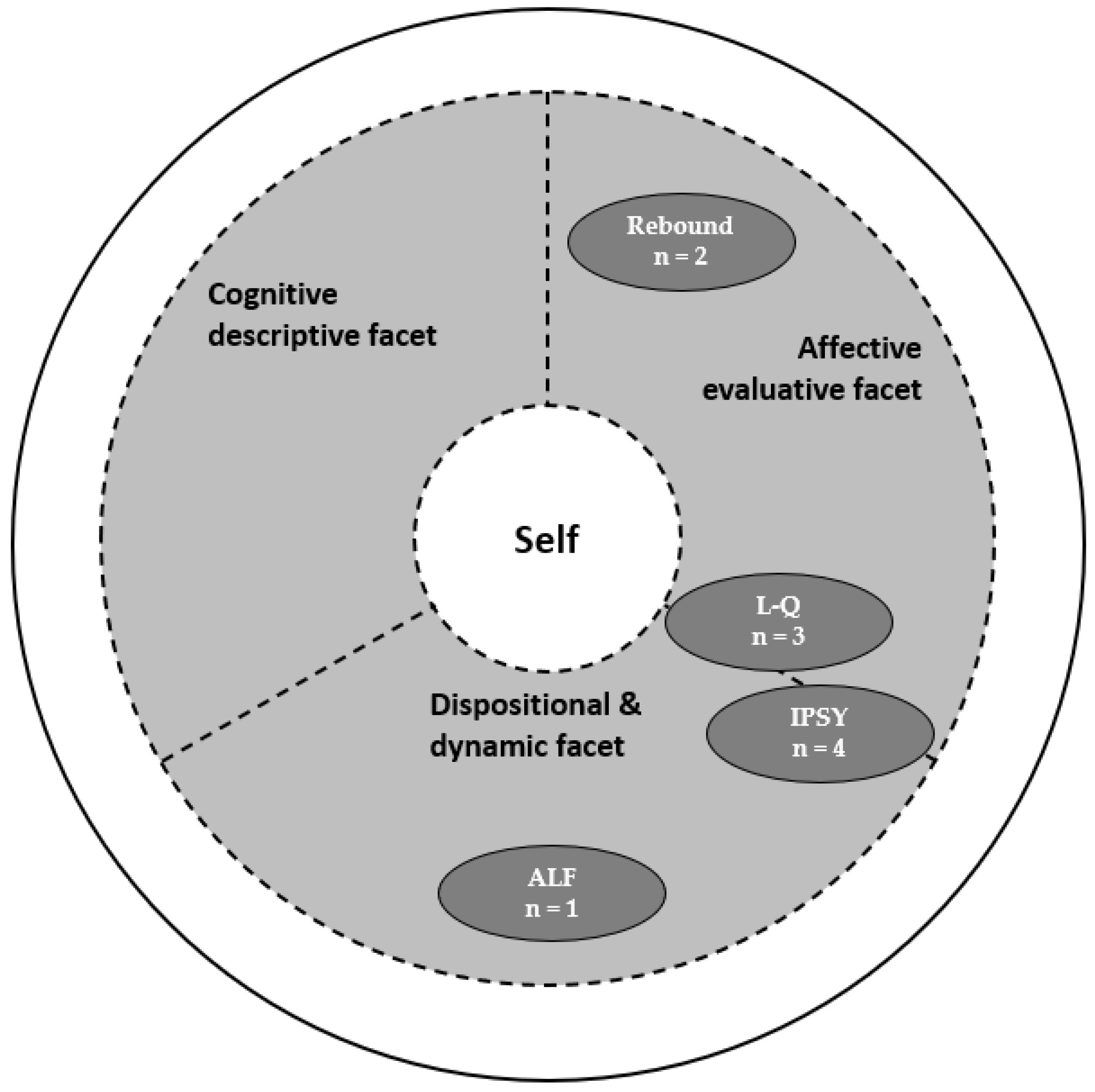

- Only the assignment of applied measuring instruments of life skills to the three facets of the self has enabled a comparative view of the evaluation results.

- It has been shown that the three facets of the self have been studied differently. Most measurements refer to the affective evaluative facet of the self, followed by the dispositional & dynamic facet. The cognitive descriptive facet of the self has been measured in a single case.

- A total of 38 instruments of varying proven quality has been used to evaluate life skills (affective evaluative facet of the self: n = 22, of which validated: n = 8, dispositional & dynamic facet of the self: n = 15, of which validated: n = 10, cognitive descriptive facet of the self: n = 1, validated).

- Overall, the evaluations of the IPSY and L-Q programs show effectiveness in promoting the affective evaluative as well as the dispositional & dynamic facet of the self. While for Rebound effects only in the affective evaluative and for ALF only in the dispositional & dynamic facet of the self are reported.

- A significant promotion of skills has been measured with the already validated measurement instruments in the area of the affective evaluative facet of the self with “Expectation regular use: tobacco” (IPSY) and “Self-esteem 2” (L-Q) as well as in the area of the dispositional & dynamic facet of the self with “Resistance to Peer Pressure” (IPSY) and “Life Skills Resources” (ALF).

4.1. Quality of Evidence

4.2. Comparative Effectiveness of LSPs

4.3. Differentiation of the LSPs Due to Program Design and Proven Effects

4.4. Blind Spots

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Conclusions

- As of now, the health-promoting potential of LSPs already appears to be greater than the effects in the area of health behavior that have been proven so far. In order to be able to systematically capture this potential, a consensus is needed on the procedure for evaluations. This refers to the study design and especially to the selection of standardized, valid measurement instruments for life skills [80].

- Life skills are general competencies that contribute to coping with everyday challenges. They have a protective effect not only in relation to addiction. They generally serve to reduce behavior-related health risks [12].

- This could make them particularly relevant in a world that is becoming increasingly characterized by uncertainties. Key social problems are coming to a head and require sustainable solutions. Life skills could provide both individual and societal benefits.

- At the individual level, they can contribute to constructive coping with stress, effective communication, self-regulation, and decision-making in a dynamic world. Harmful coping behaviors can be reduced, which has an impact on both physical and mental health.

- Societal benefits could result from even small improvements in life skills. This could have a major impact on health-promoting behavior over the lifespan, reducing the burden of disease and thus the health care system.

- In addition, the training of core life skills (e.g., self awareness, critical thinking, decision making) can contribute to the formation and reflection of individual and social values. They can therefore contribute to democratic competence in general.

- Specifically, e.g., role adoption (empathy), the ability to deal with conflict (coping with stress & emotions, self-awareness, communication, interpersonal relationship skills), sociological analysis (critical thinking, creative thinking), political judgment (decision making, critical thinking) and the ability to participate (decision making, problem solving) can contribute to democratic maturity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Source | Search Strategy | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| ERIC MEDLINE PsycINFO PSYNDEX | AB school OR AB classroom OR AB school-based OR school-setting | ERIC: 178 MEDLINE: 755 PsycINFO: 2078 PSYNDEX: 470 |

| AB skill training OR training program OR AB evaluation OR AB prevention OR AB intervention OR AB education OR health promotion OR educational intervention OR life skills | ||

| AB RCT OR AB randomized controlled trialr OR AB quantitative OR AB control OR AB pre OR AB post OR AB quasi-experiment OR AB quasi-experimental OR AB follow-up OR AB meta-analysis OR AB review | ||

| TX german OR TX Germany OR TX german language OR german speaking | ||

| AB stress management OR AB coping OR AB anxiety OR AB depression OR AB emotion OR AB awareness OR AB problem solving OR AB life skills OR AB peer pressure OR AB assertive behavior OR AB behavior problems OR AB externalizing behavior OR AB motivational enhancement OR AB life coping skills OR AB decision making OR AB mental health OR AB coping strategy OR AB social skills OR AB social competence OR AB perspective taking or perspective-taking OR AB behavior adjustment OR AB social support OR AB self-efficacy OR AB stress management OR AB emotional self-control OR AB emotional self-regulation OR AB psychosocial problems OR AB awareness training OR AB self-reflection or self-evaluation or self-awareness OR AB goal setting OR AB well-being or wellbeing or well being OR AB antisocial behavior OR AB social learning OR AB emotional learning OR AB alcohol OR AB smoking OR AB drug addiction or drug abuse or substance abuse | ||

| FIS-Bildung | Schlagwörter: LEBENSKOMPETENZ oder Schlagwörter: LIFE und SKILLS oder Freitext: LEBENSKOMPETENZ * oder Freitext: “LIFE SKILLS” | 114 |

| Schlagwörter: SCHUL * | ||

| Total: 3595 |

| Source | Search Strategy | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| ERIC MEDLINE PsycINFO PSYNDEX | TX Lebenskompeten * OR TX Kompetenz OR TX Programm OR TX life skill * OR TX competence OR TX program * | ERIC: 137 MEDLINE: 1416 PsycINFO: 327 PSYNDEX: 77 |

| TX unplugged OR TX rebound OR TX alf OR TX Lions Quest OR TX IPSY OR TX “Fit und Stark” | ||

| Limiters—Published Date: 19940101–20210331; Publication Year: 1994–2021 | ||

| FIS-Bildung | Freitext: Unplugged; Freitext: Rebound; Freitext ALF; Freitext IPSY; Freitext: Lions Quest, Freitext: “Fit und Stark” | 478 |

| Total: 2435 |

Appendix B

| n | Name of Program | Setting | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ALF | Secondary school I | Addiction prevention |

| 2 | FRIENDS | Primary school | Anxiety disorder |

| 3 | Anti-Stress-Training | Primary school | Stress prevention |

| 4 | Balu und Du | Primary school | unspecific |

| 5 | Be smart—Don’t start | Secondary school I: competition | Addiction prevention |

| 6 | EFFEKT | Preschool | Social behavior |

| 7 | Emotionsregulationstraining für das Kindesalter | Primary school | Emotional regulation |

| 8 | Emotionstraining in der Schule | 10–13 years old | Depression |

| 9 | fairplayer.manual | Adolescence | Bullying |

| 10 | Familien stärken | 13–17 years old & families | Addiction prevention |

| 11 | Faustlos | Kindergarten/Primary school | Violence prevention |

| 12 | FearNot! | Bullying | |

| 13 | Fit Kids—fitte Kinder, fittes Kaufbeuren | community-oriented | Addiction prevention |

| 14 | Fit und Stark 1 & 2 | 1st & 2nd grade | unspecific |

| 15 | Fit und Stark 3 & 4 | community-oriented | Addiction prevention |

| 16 | Fit und Stark 5 & 6 | Secondary school I | Addiction prevention |

| 17 | Friedliches Miteinander in Streitsituationen | Primary school | Social and emotional learning |

| 18 | Heidelberger Kompetenztraining (HKT) | Youth athletes | Doping prevention |

| 19 | IPSY | Secondary school I | Addiction prevention |

| 20 | JobFit | End of school | Unspecific |

| 21 | Klar bleiben | 10th grade | Binge drinking |

| 22 | Klasse 2000 | Primary school | Addiction prevention |

| 23 | LARS & LISA | Secondary school I | Depression |

| 24 | Life Skills Through games | Not specified | Unspecific |

| 25 | Lions Quest: eigenständig werden | Not specified | Unspecific |

| 26 | Lions-Quest: erwachsen werden | Secondary school I | Addiction prevention |

| 27 | LISA-T | 8th grade | Depression |

| 28 | MaiStep | Secondary school I | Eating disorder |

| 29 | Medienhelden | Secondary school I | Cyberbullying |

| 30 | MIndMatters | Entire school | School climate |

| 31 | PeP | Pupils with special needs | Addiction & violence prevention |

| 32 | ProACT + E | Secondary school I | Bullying |

| 33 | Rebound | Secondary school I | Addiction prevention |

| 34 | Surf fair | Secondary school I | Cyberbullying |

| 35 | TIP | 2nd & 3rd grade | Problem solving |

| 36 | TRIPLE P | Not specified | Mental health |

| 37 | Unplugged | Secondary school I | Addiction prevention |

| 38 | Verhaltenstraining in der Grundschule | 3. und 4. Klasse | Social competence |

| 39 | ViSC | 5 − 8. Klasse | unspecific |

| Study | Reason |

|---|---|

| [33] | Review contains an evaluation, which was considered in this work |

| [63] | Program manual (ALF) |

| [66] | Program manual (IPSY) |

| [62] | Program manual (L-Q) |

| [81] | No evaluation |

| [82] | No evaluation |

| [83] | No evaluation |

| [84] | No life skills program evaluated |

| [85] | No life skills program evaluated |

| [86] | Review on US-American evaluations |

| [87] | No German language program |

| [88] | Review contains an evaluation, which was considered in this work |

| [89] | No German language program |

| [90] | No German language program |

| [64] | No measurement in outcomes of interest |

| [91] | Program manual (Fit und Stark) |

| [92] | Evaluation study in elementary schools |

| [93] | No German language program |

| [94] | No German language program |

| [95] | No evaluation |

| [96] | No evaluation |

| [97] | No evaluation |

| [98] | No control group design |

| [99] | No evaluation |

| [100] | No evaluation |

| [101] | No measurement in outcomes of interest |

Appendix C

| ALF 1 [35,44] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | quasi-experimental study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 32 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 18.8% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | School classes |

| n intervention: | Not specified | |

| n control: | Not specified | |

| n total (Cluster): | 26 school classes | |

| Population at end of study | 436 | |

| n intervention: | 230 | |

| n control: | 206 | |

| Total (t0): | 675 | |

| Average age: | 10.4 | |

| Gender (female): | 45.5% | |

| Further characteristics | Urban area schools | |

| Intervention | LSP | ALF Pilot study with the aim to collect data on behavioral out-comes (tobacco, alcohol, drugs), attitudes towards drugs, class climate and competence in order to draw conclusions on program effectiveness. |

| Measurements: | Pre-Posttest + 2 FU-Tests | |

| Compliance | 100% of contents | |

| Intervention duration | 8 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 5th class: 12 × 90 min./school year 6th class: 6 × 90 min./school year 7th class: 6 × 90 min./school year | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | yes, 2 two-day trainings | |

| Control: | Regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | Post-Test: 8 months: - 30-day-consumption frequency tobacco: 6.9% difference. FU: 20 months: - Lifetime drunkenness experience: 9.3% difference. | |

| Outcomes not significant | Expected consequence: tobacco Expected consequence: alcohol Expected consequence: drugs Attitude towards alcohol Attitude towards cannabis Attitude towards smoking Social support Cannabis consumption Self-efficacy Knowledge about drugs Self-esteem Helplessness Social competence Classroom climate Resisting peer pressure Lifetime consumption frequencies alcohol + tobacco 30-day-consumption frequency alcohol | |

| ALF 2 [45,46] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study with quantitative and qualitative surveys |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 24 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 30.3% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | School classes |

| n intervention: | Not specified | |

| n control: | Not specified | |

| n total (Cluster): | 26 school classes | |

| Population at end of study | 448 | |

| n intervention: | 247 | |

| n control: | 201 | |

| Total (t0): | 753 | |

| Average age: | 10.8 | |

| Gender (female): | 49.8% | |

| Further characteristics | Urban area schools | |

| Intervention | LSP | ALF Quantitative survey: knowledge about life skills; Qualitative survey: application of life skills |

| Measurements: | Pre-Posttest + 1 FU-Tests | |

| Compliance | 84% of contents | |

| Intervention duration | 12 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 5th class: 12 × 90 min./school year 6th class: 8 × 90 min./school year | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | yes, 2 two-day trainings | |

| Control: | Regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | Qualitative Outcomes Posttest: 12 months: - Application of conversation rules OR = 2.87 FU: 4 months: - Application of relaxation rules OR = 4.23 Quantitative Outcomes FU: 24 months:

| |

| Outcomes not significant | Life Skills: deficits | |

| F&S 1 [53] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 15 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 12.5% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | School classes |

| n intervention: | 55 classes | |

| n control: | 51 classes | |

| n total (Cluster): | 106 classes | |

| Population at end of study | not specified | |

| n intervention: | 921 | |

| n control: | 704 | |

| Total (t0): | 1858 | |

| Average age: | 11.49 | |

| Gender (female): | 48.1% | |

| Further characteristics | Study in three European countries | |

| Intervention | LSP | F&S |

| Measurements: | Pre- and posttest | |

| Compliance | 78.1% | |

| Intervention duration | 4 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 45 min/week | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | none | |

| Control: | Regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | FU: 15 months:

| |

| Outcomes not significant | Attitudes towards smoking Perceived positive consequences of smoking Susceptibility to smoking Social competence | |

| F&S 2 + L-Q [37] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 16 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 23% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | Schools |

| n intervention: | 31 schools, 46 classes | |

| n control: | 16 schools, 45 classes | |

| n total (Cluster): | 47 | |

| Population at end of study | 1056 | |

| n intervention: | not specified | |

| n control: | not specified | |

| Total (t0): | 1370 | |

| Average age: | not specified | |

| Gender (female): | 47.1% | |

| Further characteristics | low socioeconomic status, two LSPs were implemented. | |

| Intervention | LSP | F&S, L-Q |

| Measurements: | Pre-posttest + 1FU test | |

| Compliance | At least 60% | |

| Intervention duration | 1 school year | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 1 lesson per week | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | none | |

| Control: | Regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | FU: 16 months:

| |

| Outcomes not significant | Self-Efficacy Social competence | |

| IPSY 1 [36,54,55,56,57,58] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 4.5 years | |

| Drop-Out: | 29% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | schools |

| n intervention: | 23 | |

| n control: | 21 | |

| n total (Cluster): | 44 | |

| Population at end of study | not specified | |

| n intervention: | not specified | |

| n control: | not specified | |

| Total (t0): | 1692 | |

| Average age: | 10.47 | |

| Gender (female): | 52.9% | |

| Further characteristics | none | |

| Intervention | LSP | IPSY |

| Measurements: | Pre-posttest + 4FU tests | |

| Compliance | 80% | |

| Intervention duration | 6 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 15 × 90 min/week in 5th grade, 7 booster sessions in each 5th and 7th grade | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | 1 day seminar | |

| Control: | Regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | Posttest: 6 months:

| |

| Outcomes not significant |

| |

| IPSY 2 [59] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 34 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 3 persons | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | School clases |

| n intervention: | 4 | |

| n control: | not specified | |

| n total (Cluster): | not specified | |

| Population at end of study | 105 | |

| n intervention: | 62 | |

| n peer intervention: | 20 | |

| n control: | 23 | |

| Total (t0): | 108 | |

| Average age: | 10.74 | |

| Gender (female): | 43.8% | |

| Further characteristics | Three arm intervention: teacher-lead, peer-lead, and control | |

| Intervention | LSP | IPSY |

| Measurements: | Pre-posttest + 1 FU test | |

| Compliance | 100% | |

| Intervention duration | 1 week | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | Full days | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | 1 day seminar | |

| Control: | School newspaper project | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | FU: 34 months

| |

| Outcomes not significant | - Resistance alcohol | |

| IPSY3 [60] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Quasi-experimental study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 18 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 27% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | schools |

| n intervention: | not specified | |

| n control: | not specified | |

| n total (Cluster): | not specified | |

| Population at end of study | 1131 | |

| n intervention: | 646 | |

| n control: | 485 | |

| Total (t0): | not specified | |

| Average age: | 10.45 | |

| Gender (female): | 53.5% | |

| Further characteristics | Comparison of Italian and German pupils. Only German population was considered | |

| Intervention | LSP | IPSY |

| Measurements: | Pre-posttest + 1 FU test | |

| Compliance | 80% | |

| Intervention duration | 6 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | not specified | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | 1 day workshop | |

| Control: | Regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | FU: 18 months

| |

| Outcomes not significant |

| |

| L-Q [52] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 15 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 21.9% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | School classes |

| n intervention: | not specified | |

| n control: | not specified | |

| n total (Cluster): | 35 classes | |

| Population at end of study | 761 | |

| n intervention: | 374 | |

| n control: | 387 | |

| Total (t0): | 974 | |

| Average age: | 10.4 (5th grade); 13.0 (7th grade) | |

| Gender (female): | 49% (5th grade); 45% (7th grade) | |

| Further characteristics | ||

| Intervention | LSP | L-Q |

| Measurements: | Pre-posttes + 1FU test | |

| Compliance | 75% (5th grade); 62% (7th grade) | |

| Intervention duration | 9 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 16 × 45 min during 1 school year | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | 3-day seminar | |

| Control: | regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | Posttest: 9 months - Lifetime consupmtion tobacco OR = 2.3 Posttest: 9 months (5th grade) - Social competence, girls F(1.317) = 12.3; p < 0.02; η2 = 0.0374 FU: 15 months - Willingness to quit smoking, girls F(1.36) = 11.8; p < 0.02; η2 = 0.0476 FU: 15 months (5th grade)

| |

| Outcomes not significant |

| |

| Rebound [47] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 10 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 36% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | classes |

| n intervention: | 29 | |

| n control: | 19 | |

| n total (Cluster): | 48 | |

| Population at end of study | 723 | |

| n intervention: | 512 | |

| n control: | 211 | |

| Total (t0): | 1125 | |

| Average age: | 14.8 | |

| Gender (female): | 51.9& | |

| Further characteristics | 9th & 10th grade | |

| Intervention | LSP | Rebound |

| Measurements: | Pre-posttest | |

| Compliance | 100% | |

| Intervention duration | 5 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 16 × 90 min in one school year | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | Yes | |

| Control: | Regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | Posttest: 5 months

| |

| Outcomes not significant |

| |

| Unplugged [48,49,50,51] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Study design: | Cluster randomized study |

| Duration from start of intervention: | 24 months | |

| Drop-Out: | 22.9% | |

| Population | Randomization type n randomized clusters | Schools |

| n intervention: | 76 | |

| n control: | 62 | |

| n total (Cluster): | 138 | |

| Population at end of study | 5541 | |

| n intervention: | 2811 | |

| n control: | 2730 | |

| Total (t0): | 7079 | |

| Average age: | 13.2 | |

| Gender (female): | 49% | |

| Further characteristics | Schools in 7 European countries | |

| Intervention | LSP | Unplugged |

| Measurements: | Pre-posttest + 1 FU test | |

| Compliance | not specified | |

| Intervention duration | 3 months | |

| Frequency (hours/week) | 12 × 90 min in 1 school year | |

| Train the trainer-workshop | 3 days seminar | |

| Control: | regular lessons | |

| Outcomes significant group differences | Posttest: 3 months

| |

| Outcomes not significant |

| |

Appendix D

| Instrument | Reason for Categorization a | Items | Example | I b | S c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards alcohol | Here, the attitude towards alcohol is directly queried. | 12 | Drinking alcohol is disgusting | [44] | |

| Attitude toward cannabis | Here, the attitude towards hashish is directly queried. | 12 | Smoking hashish is super | [44] | |

| Attitudes towards smoking 1 | Attitudes towards tobacco are asked. | 6 | Smoking is exciting | [53] | |

| Attitude towards smoking 2 | Here the attitude towards smoking is queried directly. | 16 | Cigarette smoking is disgusting | [44] | |

| Expectation regular use: alcohol | Assessment based on current attitudes toward alcohol. | 1 | How likely is it that you will drink on a regular basis during the next 12 months? | [102] | [54] |

| Expectation regular use: tobacco | Assessment based on current attitudes toward tobacco. | 1 | If you are going to smoke in the next 12 months, how often will you smoke? will that be? | [103] | [56] |

| Expected consequence: alcohol | This is an assessment on the topic of the impact of alcohol consumption. The basis for this is knowledge or ideas about drinking. These are put into a context of the own opinion. | 28 | With alcohol you can gain more confidence | [104] d | [44] |

| Expected consequence: drugs | This is an assessment on the topic of the impact of drug use. The basis for this is knowledge or ideas about drugs. These are placed in the context of one’s own opinion. | 14 | When you use drugs, you can have a say in your circle of friends | [44] | |

| Expected consequence: smoking | This is an assessment on the subject of smoking. The basis for this is knowledge or ideas about smoking. These are put into a context of the own opinion. | 15 | Smoking helps to improve mood | [44] | |

| Perceived positive consequences of smoking | An assessment of the consequences of smoking is asked. This results from knowledge or perceptions and the attitude towards smoking. | 8 | People who smoke have more fun | [53] | |

| Proneness to illicit drug use: Cannabis & Ecstasy | The attitude towards cannabis/ecstasy in general is asked. | 2 | How do you relate to… (cannabis, ecstasy) | [36] | |

| Readiness to try smoking | Assessment based on current attitudes toward tobacco. | 1 | If you don’t smoke, do you plan to smoke in the near future? | [52] | |

| Resistance certainty to refuse a cigarette offer | Evaluation of a specific situation. Involves attitude toward drugs. | 1 | How easy or difficult do you find it to say no when someone offers you a cigarette and you don’t want to smoke? | [52] | |

| Risk perception general | It is about the assessment on the basis of previous knowledge or ideas. | 3 | how risky is it (a drug) for everybody | [47] | |

| Risk perception personal | It is about the assessment on the basis of previous knowledge or ideas. | 3 | how risky is it (a drug) for me | [47] | |

| Risk perception relative | It is about the assessment on the basis of previous knowledge or ideas. | 3 | how risky is it (a drug) for me compared with for other people? | [47] | |

| Self-esteem 1 | Personality traits are assessed and the general state of health is queried. | 18 | I like myself | [105] | [44] |

| Self esteem 2 | The value that one ascribes to one’s own person is queried. | 8 | On the whole, I am satisfied with myself. | [106] | [52] |

| Self-concept of appreciation through others | Assessing the value of perceived feedback by others. | 6 | My family mistrusts me | [107] | [54] |

| Self-concept of general self-worth | An assessment of the perceived value of one’s own person takes place. | 10 | I am a nobody | [107] | [56] |

| Susceptibility to smoking | One’s own attitude toward tobacco is the basis of this assessment. | 2 | Do you think you will be smoking cigarettes 1 year from now? | [108,109] | [53] |

| Willingness to quit smoking | Assessment based on current attitudes toward tobacco. | 1 | Do you plan to quit smoking in the near future? | [52] |

| Instrument | Reason for Categorization a | Items | Example | I b | S c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helplessness | In general, situations are addressed that require action. It is true that knowledge about the person is also queried, which speaks for cognitive descriptive facet. However, there is an assessment of the expression of dispositions. This requires self-awareness. | 5 | I don’t have the patience to deal with difficult problems endlessly. | [110] | [44] |

| Life Skills Resources | Different dispositions are queried, e.g., self-awareness & self-observation. | 23 | If someone tries to persuade me, I think about what they would get out of it. | [105] f | [45],[54] |

| Life Skills Deficits | Different dispositions are queried, e.g., self-awareness & self-observation. | 13 | It’s hard for me to decide. | [45,54] | |

| Resistance alcohol | Different dispositions are queried. Among them: Emotion regulation, self-related cognitions and action dispositions. | 1 | Imagine you are at a friend s party and his/her parents are away from home. After a short while, a friend of yours opens the bar and offers alcoholic drinks to everybody at the party. How would you react? | [59] | |

| Resistance cigarette | Different dispositions are queried. Among them: Emotion regulation, self-related cognitions and action dispositions. | 1 | Not specified. Comparable to resistance to alcohol consumption | [59] | |

| Resistance to Peer Pressure | It is asked about dispositions that constitute the steadfastness of the self. | 8 | When my friends put pressure on me, I give in quickly. | [111] | [54,56] |

| Resisting peer pressure | The complexity of the knowledge about the self that is queried here goes beyond cognitive descriptive facet of the self. The question implicitly asks about the stability of the self. This requires self-confidence in addition to self-regulatory skills. | 5 | In the peer group I sometimes do something forbidden that I otherwise would not do. | [105] e | [44] |

| self-concept of problem solving skills | If a concrete situation were asked, it could be cognitive descriptive. However, the handling of the described scenarios is to be recorded in general. This requires an assessment of underlying dispositions. | 10 | I try to run away from my problems. | [107] | [54,56] |

| self-concept of stability against groups | If a concrete situation were asked, it could be cognitive descriptive. However, the handling of the described scenarios is to be recorded in general. This requires an assessment of underlying dispositions. | 12 | I have a hard time expressing my opinion in front of a larger group. | [107] | [54,56] |

| Self-efficacy 1 | General requirements are asked for, which may require different dispositions. Since there is no specific focus on self-concepts, cognitive descriptive aspects are excluded. | 15 | In unexpected situations I always know how to behave. | [105] | [44] |

| Social competence 1 | General requirements are asked for, which may require different dispositions. Since there is no specific focus on self-concepts, cognitive descriptive aspects are excluded. | ||||

| Self-Efficacy 2 | Self-efficacy expectancy is the disposition to act, to solve new or complicated problems based on one’s own competencies. | 5 | For every problem I can find a solution. | [112] g [113] h [114] i | [37] |

| Social competence 2 | In exemplary scenarios, one’s own behavior is assessed. This requires social competence, self-perception, self-efficacy expectations and other dispositions for action. | 7 | How easy or hard are the following things for you....: Saying “no” when someone asks you to do something you don’t want to do. | [52],[37] | |

| Social competence 3 | General scenarios are asked for. The aim is to assess how easy these are for the students. In other words, the students are asked about their social competence—a disposition for action. | 13 | To talk in front of large groups. | [53] | |

| Tobacco consumption intention | Implicitly questions dispositions to act but also regulatory ability. | 1 | Will you smoke in the next 12 months? | [56] |

| Instrument | Reason for Categorization a | Items | Example | I b | S c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | Here, elements of the social self are asked for [28]. It is about knowledge about social structures on which one can rely. | 8 | I have friends who stand by me even when I have done something stupid. | [115] d | [44] |

References

- Quenzel, G.; Hurrelmann, K. Lebensphase Jugend: Eine Einführung in die Sozialwissenschaftliche Jugendforschung; 14. Auflage; Juventa Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2022; ISBN 9783779957393. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrelmann, K.; Quenzel, G. (Eds.) Lebensphase Jugend: Eine Einführung in die Sozialwissenschaftliche Jugendforschung; 11 Vollst. überarb. Aufl.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2012; ISBN 9783779926009. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrelmann, K.; Richter, M. Risk behaviour in adolescence: The relationship between developmental and health problems. J. Public Health 2006, 14, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, Z.; Bukoski, W.J. (Eds.) Handbook of Drug Abuse Prevention; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780387354088. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, B.; Merkel, C. Die Drogenaffinität Jugendlicher in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2019; Rauchen, Alkoholkonsum und Konsum illegaler Drogen, Aktuelle Verbreitung und Trends: Cologne, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M.; Silbereisen, R.K. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung im Jugendalter. In Lehrbuch Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung; 4. vollständig überarbeitete Auflage; Hurrelmann, K., Klotz, T., Haisch, J., Eds.; Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 70–78. ISBN 345685319X. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, T. Frühe Weichenstellung: Zur Bedeutung der Kindheit und Jugend für die Gesundheit im späteren Leben. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2010, 53, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiher, J.; Kuntz, B.; Lange, C. Rauchen bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. J. Health Monit. 2017, 2, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.J. Adolescent alcohol use: Risks and consequences. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014, 49, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzkowiak, P.; Schlömer, H. Entwicklung der Suchtprävention in Deutschland: Konzepte und Praxis. Suchttherapie 2003, 4, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Life Skills Education for Children and Adolescents in Schools; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Partners in Life Skills Education; World Health Organization Department of Mental Health: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin, G.J.; Eng, A.; Williams, C.L. Preventing the onset of cigarette smoking through life skills training. Prev. Med. 1980, 9, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altgeld, T.; Kolip, P. Konzepte und Strategien der Gesundheitsförderung. In Lehrbuch Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung; 4., vollständig überarbeitete Auflage; Hurrelmann, K., Klotz, T., Haisch, J., Eds.; Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 70–78. ISBN 345685319X. [Google Scholar]

- Jerusalem, M.; Meixner, S. Lebenskompetenzen. In Psychologische Förder- und Interventionsprogramme für das Kindes- und Jugendalter; Lohaus, A., Domsch, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 141–157. ISBN 978-3-540-88384-5. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin, G.J.; Griffin, K.W. School-based programmes to prevent alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2007, 19, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, A.; Thrul, J. Expertise zur Suchtprävention; BZgA, Bundeszentrale für Gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Cologne, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Kober, H. Lernen am Modell: Ansätze zu Einer Sozial-Kognitiven Lerntheorie; 1. Aufl.; Klett: Stuttgart, Germany, 1976; ISBN 312920590X. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor, R.; Jessor, S.L. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.; Dannemann, S.; Gropengießer, I.; Heuckmann, B.; Kahl, L.; Schaal, S.; Schaal, S.; Schlüter, K.; Schwanewedel, J.; Simon, U.; et al. Modell zur reflexiven gesundheitsbezogenen Handlungsfähigkeit aus biologiedidaktischer Perspektive. Biol. Unserer. Zeit. 2019, 49, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauthmann, J.F. Persönlichkeitspsychologie: Paradigmen—Strömungen—Theorien; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-662-53003-0. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, H.; Rammsayer, T. (Eds.) Handbuch der Persönlichkeitspsychologie und Differentiellen Psychologie; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2005; ISBN 3801718557. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf, J.B.; Neyer, F.J. Psychologie der Persönlichkeit: Mit 110 Tabellen; 5. Vollst. Überarb. Aufl.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 9783642302640. [Google Scholar]

- Kalthoff, R.A.; Neimeyer, R.A. Self-complexity and psychological distress: A test of the buffering model. Int. J. Pers. Constr. Psychol. 1993, 6, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyer, F.J.; Asendorpf, J.B. (Eds.) Psychologie der Persönlichkeit; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- James, W. The Principles of Psychology; Henry Holt & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, N.S.; Roona, M.R.; Ochshorn, P.; Marshall, D.G.; Streke, A.V.; Stackpole, K.M. School-Based Adolescent Drug Prevention Programs: 1998 Meta-Analysis. J. Prim. Prev. 2000, 20, 275–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, A. Meta-Analyse zur Wirksamkeit deutscher suchtpräventiver Lebenskompetenzprogramme. Kindh. Entwickl. 2016, 25, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelmann, A.; Pfost, M.; Schmitt, C. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Z. Gesundh. 2014, 22, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botvin, G.J.; Griffin, K.W. Life Skills Training: Empirical Findings and Future Directions. J. Prim. Prev. 2004, 25, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxcroft, D.R.; Tsertsvadze, A. Universal school-based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 5, CD009113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, B. Die Drogenaffinität Jugendliche in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2015; BZgA, Bundeszentrale für Gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Cologne, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, C.; Reese, A. Schulische Suchtprävention nach dem Lebenskompetenzkonzept—Ergebnisse einer vierjährigen Interventionsstudie. SUCHT 2000, 46, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichold, K.; Blumenthal, A. Long-Term Effects of the Life Skills Program IPSY on Substance Use: Results of a 4.5-Year Longitudinal Study. Prev. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Prev. Res. 2016, 17, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menrath, I.; Mueller-Godeffroy, E.; Pruessmann, C.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Ottova, V.; Pruessmann, M.; Erhart, M.; Hillebrandt, D.; Thyen, U. Evaluation of school-based life skills programmes in a high-risk sample: A controlled longitudinal multi-centre study. J. Public Health 2012, 20, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Kunz, R.; Kleijnen, J.; Antes, G. Systematische Übersichten und Meta-Analysen: Ein Handbuch für Ärzte in Klinik und Praxis Sowie Experten im Gesundheitswesen; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; ISBN 9783540439363. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, W.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Nishikawa, J.; Hayward, R.S. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club 1995, 123, A12–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blümle, A.; Sow, D.; Nothacker, M.; Schaefer, C.; Motschall, E.; Boeker, M.; Lang, B.; Kopp, I.; Meerpohl, J.J. Manual Systematische Recherche für Evidenzsynthesen und Leitlinien; Albert Ludwigs Universität Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Campbell Collaboration. Evidence Synthesis Tools for Campbell Authors. Available online: https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/research-resources/resources.html (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Kutza, R. Prozeßevaluation des schulischen Lebenskompetenzprogrammes ALF zur Primärprävention des Substanzmißbrauchs: Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.). Ph.D. Thesis, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler, A.; Schröder, E.; Silbereisen, R.K. Welche Lebensfertigkeiten fördert ein suchtpräventives Lebenskompetenzprogramm? Z. Gesundh. 2007, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, A.; Schröder, E.; Silbereisen, R.K. The role of life skills promotion in substance abuse prevention: A mediation analysis. Health Educ. Res. 2008, 23, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungaberle, H.; Nagy, E. Pilot Evaluation Study of the Life Skills Program REBOUND. SAGE Open 2015, 5, 215824401561751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggiano, F.; Vigna-Taglianti, F.; Burkhart, G.; Bohrn, K.; Cuomo, L.; Gregori, D.; Panella, M.; Scatigna, M.; Siliquini, R.; Varona, L.; et al. The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: 18-month follow-up of the EU-Dap cluster randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 108, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigna-Taglianti, F.D.; Galanti, M.R.; Burkhart, G.; Caria, M.P.; Vadrucci, S.; Faggiano, F. “Unplugged”, a European school-based program for substance use prevention among adolescents: Overview of results from the EU-Dap trial. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2014, 67–82, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caria, M.P.; Faggiano, F.; Bellocco, R.; Galanti, M.R. Effects of a school-based prevention program on European adolescents’ patterns of alcohol use. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2011, 48, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, F.; Vigna-Taglianti, F.; Rosaria Galanti, M.; Scatigna, M.; Faggiano, F. Short-term mediating factors of a school-based intervention to prevent youth substance use in Europe. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2014, 54, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähnert, H. Evaluation des schulischen Lebenskompetenzförderprogramms „Erwachsen werden“: Dissertation zur Erlangung des Gesundheitswissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades an der Fakultät für Gesundheitswissenschaften der Universität Bielefeld. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel, R.; Asshauer, M. Fifteen-month follow-up results of a school-based life-skills approach to smoking prevention. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 19, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichold, K.; Brambosch, A.; Silbereisen, R.K. Do Girls Profit More? Gender-Specific Effectiveness of a Life Skills Program Against Alcohol Consumption in Early Adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 2012, 32, 200–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichold, K.; Tomasik, M.J.; Silbereisen, R.K.; Spaeth, M. The Effectiveness of the Life Skills Program IPSY for the Prevention of Adolescent Tobacco Use. J. Early Adolesc. 2016, 36, 881–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, V.; Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K. Schultypspezifische Wirksamkeit eines Lebenskompetenzprogramms zur Beeinflussung des Tabakkonsums von Schülern in Gymnasien und Regelschulen. SUCHT 2007, 53, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaeth, M.; Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K.; Wiesner, M. Examining the differential effectiveness of a life skills program (IPSY) on alcohol use trajectories in early adolescence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, V.; Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K. The life skills program IPSY: Positive influences on school bonding and prevention of substance misuse. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K. Peers and Teachers as Facilitators of the Life Skills Program IPSY. SUCHT 2012, 58, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, F.; Weichold, K. Evaluation of a Life Skills Program to Prevent Adolescent Alcohol Use in Two European Countries: One-Year Follow-Up. Child. Youth Care Forum 2016, 45, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut für Sozial- und Gesundheitspsychologie Wien. Unplugged LehrerInnenhandbuch: Prävention in der Schule; Turin: Wien, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilms, E.; Wilms, H. Lions-Quest “Erwachsen warden”: Lebenskompetenzen für Kinder und Jugendliche der Sekundarstufe I, 5th ed.; Lions Deutschland: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- IFT Institut für Therapieforschung. Allgemeine Lebenskompetenzen und Fertigkeiten: ALF; Programm für Schüler und Schülerinnen der 5. Klasse mit Informationen zu Nikotin und Alkohol. In Lehrermanual mit Kopiervorlagen zur Unterrichtsgestaltung; 2., korr. Aufl.; Schneider-Verl. Hohengehren: Baltmannsweiler, Germany, 2000; ISBN 389676215X. [Google Scholar]

- Aßhauer, M.; Hanewinkel, R. Fit und stark fürs Leben—Persönlichkeitsförderung und Prävention des Rauchens in der Schule. Suchtreport 1998, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Burow, F.; Aßhauer, M.; Hanewinkel, R. Fit und Stark Fürs Leben; 1. Aufl.; Klett-Schulbuchverl Leipzig: Leipzig, Germany, 2002; ISBN 312196139X. [Google Scholar]

- Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K. Suchtprävention in der Schule: IPSY—Ein Lebenskompetenzprogramm für die Klassenstufen 5–7, Online-Ausg; Online-Ausg; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany; Bern, Germany; Wien, Austria, 2014; ISBN 9783840921292. [Google Scholar]

- Jungaberle, H.; Nagy, E.; von Heyden, M.; Schultka, V.; Lieneweg, S.; DuBois, F. Rebound Curriculum 1.0: Stärken Bewusst Machen und fördern. Lernen mit Alkohol und Drogen Umzugehen; Manual und Studienbuch für Kursleitende, FINDER Akademie: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgie, J.M.; Sean, H.; Deborah, M.C.; Matthew, H.; Rona, C. Peer-led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol and/or drug use among young people aged 11-21 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2016, 111, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinke, S.P.; Blythe, B.J. Cognitive-Behavioral Prevention of Children’s Smoking. Child. Behav. Ther. 1982, 3, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; Barnes, S.P.; Bailey, R.; Doolittle, E.J. Promoting social and emotional competencies in elementary school. Future Child. 2017, 27, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K. Die Bedeutung instruktionaler Kohärenz für eine systematische Kompetenzentwicklung. Unterrichtswiss 2020, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, E.; Keller, R. Age-Specific Life Skills Education in School: A Systematic Review. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinarić, M.; Günther, S.; Moor, I.; Winter, K.; Hoffmann, L.; Richter, M. Der Zusammenhang zwischen schulischer Tabakkontrolle und der wahrgenommenen Raucherprävalenz Jugendlicher. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2021, 64, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, B.; Merkel, C. Der Substanzkonsum Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des Alkoholsurveys 2021 zu Alkohol, Rauchen, Cannabis und Trends; BZgA, Bundeszentrale für Gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Cologne, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, A. Entwicklungsorientierte Evaluation Eines Suchtpräventiven Lebenskompetenzprogramms; Dissertationsschrift: München, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Elbers, R.G.; Reeves, B.C.; Development Group for ROBINS-I. Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I): Detailed Guidance 2016, Updated 12 October 2016. Available online: http://www.riskofbias.info (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Angelucci, M.; Di Maro, V. Program. Evaluation and Spillover Effects; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, S. The self-concept revisited. Or a theory of a theory. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, P.R.; Altman, D.G.; Bagley, H.; Barnes, K.L.; Blazeby, J.M.; Brookes, S.T.; Clarke, M.; Gargon, E.; Gorst, S.; Harman, N.; et al. The COMET Handbook: Version 1.0. Trials 2017, 18, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.H.; Jean-Marie, G.; Beck, J. Resilience and Risk Competence in Schools: Theory/Knowledge and International Application in Project REBOUND. J. Drug Educ. 2010, 40, 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Heyden, M.; Löhner, B. Rebound—Lebenskompetenz- und Risikokompetenzprogramm. Pro Jugend Fachz. der Aktion Jugendschutz Landesarb. Bayern e.V. 2020, 1, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kröninger-Jungaberle, H.; Nagy, E.; von Heyden, M.; DuBois, F.; Ullrich, J.; Wippermann, C.; Pospiech, B.; Gordon, V.; Haubold, L.; Breitner, S.; et al. REBOUND: A media-based life skills and risk education programme. Health Educ. J. 2015, 74, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Sonnberger, M.; Deuschle, J. Rebound-Effekte aus Sozialwissenschaftlicher Perspektive—Ergebnisse aus Fokusgruppen im Rahmen des REBOUND-Projektes; Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation S 5/2012, Karlsruhe. 2012. Available online: https://www.isi.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/isi/dokumente/sustainability-innovation/2012/WP05-2012_Rebound-Fokusgruppen.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Peters, A.; Sonnberger, M.; Dütschke, E.; Deuschle, J. Heoretical Perspective on Rebound Effects from a Social Science Point of view—Working Paper to Prepare Empirical Psychological and Sociological Studies in the REBOUND Project; Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation S 2/2012; Fraunhofer-Institut für System- und Innovationsforschung ISI: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, A.B.; Falco, M.; Hocini, S. Independent Evaluation of Middle School-Based Drug Prevention Curricula: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, J.Y.; Cogo-Moreira, H.; Swardfager, W.; Sanchez, Z.M. A latent transition analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial for drug use prevention. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agabio, R.; Trincas, G.; Floris, F.; Mura, G.; Sancassiani, F.; Angermeyer, M.C. A Systematic Review of School-Based Alcohol and other Drug Prevention Programs. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2015, 11, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisen, M.; Zellman, G.L.; Murray, D.M. Evaluating the Lions–Quest “Skills for Adolescence” drug education program. Addict. Behav. 2003, 28, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switzer, J.L. Evaluation of the intervention efficacy of Lions Quest Skills for Adolescence. Ph.D. Dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel, R.; Aßhauer, M. „Fit und stark fürs Leben”—Universelle Prävention des Rauchens durch Vermittlung psychosozialer Kompetenzen. Suchttherapie 2003, 4, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olbrich, R. (Ed.) Suchtbehandlung: Neue Therapieansätze zur Alkoholkrankheit und Anderen Suchtformen; Roderer: Regensburg, Germany, 2001; ISBN 3897832224. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrhelik, R.; Duncan, A.; Lee, M.H.; Stastna, L.; Furr-Holden, C.D.M.; Miovsky, M. Sex specific trajectories in cigarette smoking behaviors among students participating in the unplugged school-based randomized control trial for substance use prevention. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gol-Guven, M. The effectiveness of the Lions Quest Program: Skills for Growing on school climate, students’ behaviors, perceptions of school, and conflict resolution skills. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 25, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadrucci, S.; Vigna-Taglianti, F.D.; van der Kreeft, P.; Vassara, M.; Scatigna, M.; Faggiano, F.; Burkhart, G. The theoretical model of the school-based prevention programme Unplugged. Glob. Health Promot. 2016, 23, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichold, K. Translation of etiology into evidence-based prevention: The life skills program IPSY. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2014, 83–94, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kreeft, P.; Wiborg, G.; Galanti, M.R.; Siliquini, R.; Bohrn, K.; Scatigna, M.; Lindahl, A.-M.; Melero, J.C.; Vassara, M.; Faggiano, F.; et al. ‘Unplugged’: A new European school programme against substance abuse. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2009, 16, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obbarius, V. Wirkfaktoren des schulbasierten suchtpräventiven Lebenskompetenzprogramms IPSY für die Beeinflussung des Tabak- und Alkoholkonsums in der Adoleszenz: Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades. Ph.D. Thesis, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Jena, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kähnert, H. Life-skills Programme an deutschen Schulen. Wirkung für die Nikotinprävention. pro Jugend 2004, 2, S11–S14. [Google Scholar]

- Karing, C.; Beelmann, A. Wirksamkeit und Implementation von Präventionsmaßnahmen in der Schule. Empirische Pädagogik 2016, 30, 302–319. [Google Scholar]

- Matischek-Jauk, M.; Krammer, G.; Reicher, H. The life-skills program Lions Quest in Austrian schools: Implementation and outcomes. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersch, B.; Petermann, H.; Fischer, V. Alkoholdistanz—Ein Evaluationskriterium schulischer Sucht- und Drogenprävention. Kindh. Entwickl. 1998, 7, 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kersch, B. “Tabakdistanz”—ein Evaluationskriterium unterrichtlicher Suchtpraeventionsmassnahmen bei 13- bis 16jaehrigen Schuelerinnen und Schuelern. Ergebnisse einer Leipziger Laengsschnittstudie. SUCHT 1998, 44, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hibell, B. The1995 ESPAD Report: Alcohol and Other Drugs Use among Student in 26 European Countries; Pompidou Group, Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1997; ISBN 91-7278-065-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, J.E.; Jason, L. Preventing Substance Abuse among Children and Adolescents, 1st ed.; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fend, H.; Helmke, A.; Richter, P. Inventar zu Selbstkonzept und Selbstvertrauen; University Konstanz: Konstanz, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Deusinger, I.M. Die Frankfurter Selbstkonzeptskalen: (FSKN); Handanweisung Mit Bericht Über Vielfältige Validierungsstudien; Verlag für Psychologie Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C. Cognitive susceptibility to smoking and initiation of smoking during childhood: A longitudinal study. Prev. Med. 1998, 27, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.P.; Choi, W.S.; Gilpin, E.A.; Farkas, A.J.; Merritt, R.K. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996, 15, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem, M.; Schwarzer, R. Skala allgemeine Hilflosigkeit. In Skalen zur Befindlichkeit und Persönlichkeit: Forschungsbericht Nr. 5.; Schwarzer, R., Ed.; Institut for Psychology, Freie Universität: Berlin, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Santor, D.A.; Messervey, D.; Kusumakar, V. Measuring Peer Pressure, Popularity, and Conformity in Adolescent Boys and Girls: Predicting School Performance, Sexual Attitudes, and Substance Abuse. J. Youth Adolesc. 2000, 29, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. (Ed.) Skalen zur Erfassung von Lehrer- und Schülermerkmalen: Dokumentation der Psychometrischen Verfahren im Rahmen der Wissenschaftlichen Begleitung des Modellversuchs Selbstwirksame Schulen; R. Schwarzer: Berlin, Germany, 1999; ISBN 3-00-003708-X. [Google Scholar]

- Grob, A.; Lüthi, R.; Kaiser, F.G.; Flammer, A.; Mackinnon, A.; Wearing, A.J. Berner Fragebogen zum Wohlbefinden Jugendlicher (BFW). Diagnostica 1991, 11, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, R.; Rasky, E.; Noack, R.A. Indikatoren für Gesundheitsförderung in der Volksschule: Forschungsbericht 95/1 No. 1; Forschungsbericht: Graz, Austria, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, G.; Fydrich, T. Soziale Unterstützung, Diagnostik, Konzepte, Fragebogen F-SozU; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verhaltenstherapi: Tübingen, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

| Core Life Skill | Brief Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | coping with emotions | The ability to recognize and deal appropriately with emotions and their effects [12]. |

| 2. | coping with stress | The ability to recognize sources of stress and deal with them constructively [12]. |

| 3. | creative thinking | The ability to think about alternatives and consequences of one’s own actions [12]. |

| 4. | critical thinking | The ability to examine experiences and information objectively [12]. |

| 5. | decision-making | The ability to make (far-reaching) constructive decisions [12]. |

| 6. | effective communication | The ability to communicate adequately. Both verbally and nonverbally [12]. |

| 7. | empathy | The ability to imagine oneself in the situation of others, even if their situation is unfamiliar [12]. |

| 8. | interpersonal relationship skills | The ability to enter into and maintain constructive relationships. Also, the ability to end relationships [12]. |

| 9. | problem solving | The skill to find constructive solutions to complex problems [12]. |

| 10. | self-awareness | The ability to recognize oneself, one’s characteristics and moods [12]. |

| Study | Measurement | Missing Data | Deviation from Intervention Plan | Classification of Interventions | Selection | Confounding | Selective Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALF 1 [35,44] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L |

| ALF 2 [45,46] | M | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Rebound [47] | M | H | L | L | L | L | L |

| Unplugged [48,49,50,51] | M | L | U | L | L | L | L |

| L-Q [52] | M | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| F&S 1 [53] | M | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| F&S 2 [37] | M | H | H | M | L | L | L |

| IPSY 1 [36,54,55,56,57,58] | M | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| IPSY 2 [59] | M | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| IPSY 3 [60] | M | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Publisher | Year a | Program Target | Target Group | Time in Minutes | TTT b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALF | [63] | 2000 | Alcohol and tobacco prevention | Lower secondary education | 12 × 90 = 1080 | Optional/2 days |

| F&S | [65] | 2005 | Addiction prevention | 5th & 6th grade | 21 × 45 = 945 | none |

| IPSY | [66] | 2014 | Alcohol and tobacco prevention | 10–15 years old | 10 × 90 = 900 & 5 × 45 c = 225 | optional/1 day |

| L-Q | [62] | 2000 | Addiction prevention | 10–15 years old | 70 × 45 d = 3150 | Mandatory/3 days |

| Rebound | [67] | 2014 | Addiction prevention | Secondary education | 16 × 90 = 1440 | optional |

| Unplugged | [61] | 2009 | Addiction prevention | 12–14 years old | 12 × 50 = 600 | optional/3 days |

| Randomization by Classes | ||||||||||

| Studies | Year a | n | Control b | Follow Up in Months c | Instruments Applied d | Compliance in Percent e | ||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | ||||||

| ALF 2 [45,46] | - | 753 | R | 12 | 12 | - | - | - | 12 | 84% (907) |

| Rebound [47] | 2011 | 1125 | R | 10 | - | - | - | - | 15 | 100% (1440) |

| L-Q [52] | 2000 | 974 | R | 9 | 6 | - | - | - | 7 | 75% f (540)/62% g (446) |

| F&S 1 [53] | 1998 | 1858 | R | 15 | - | - | - | - | 8 | 78% (738) |

| IPSY 2 [59] | - | 105 | S | 10 | 24 | - | - | - | 9 | 66% (900) |

| Randomization by schools | ||||||||||

| Studies | Year a | n | Control b | Follow up in months c | Instruments applied d | Compliance in percent e | ||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | ||||||

| Unplugged [48,49,50,51] | 2004 | 7079 | R | 6 | 18 | - | - | - | 2 | not specified |

| F&S 2 h [37] | - | 1370 | R | 10 | 6 | - | - | - | 5 | at least 60% |

| IPSY 1 [36,54,55,56,57,58] | 2003 | 1692 | R | 6 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 21 | 80% (1080) |

| Quasi-experimental design | ||||||||||

| Studies | Year a | n | Control b | Follow up in months c | Applied Instruments d | Compliance in percent e | ||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | ||||||

| ALF 1 [35,44] | 1995 | 675 | R | 8 | 12 | 12 | - | - | 20 | 100% (1080) |

| IPSY 3 [60] | - | 1131 | R | 6 | 12 | - | - | - | 13 | 80% (1080) |

| Study | Age (M) | Gender (♀) | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALF 1 [35,44] | 10.4 | 45.5% | Secondary schools, Munich (Bavaria) |

| ALF 2 [45,46] | 10.8 | 49.8% | Secondary schools, Gütersloh (NRW) |

| Rebound [47] | 14.8 | 51.9% | 9th & 10th grades, southern Germany |

| Unplugged [48,49,50,51] | 13.2 | 49% | Schools in 7 European countries |

| L-Q [52] | 10.4/13.0 a | 49%/45% | 5th & 7th grades in Lübbecke (NRW) |

| F&S 1 [53] | 11.49 | 48.1% | Schools in Germany, Austria, Denmark & Luxembourg |

| F&S 2 [37] | not specified | 47.1% | not specified |

| IPSY 1 [36,54,55,56,57,58] | 10.47 | 52.9% | Grammar & secondary schools, Thuringia |

| IPSY 2 [59] | 10.74 | 43.8% | Grammar & secondary schools, Thuringia |

| IPSY 3 [60] | 10.45 | 53.5% | Grammar & secondary schools, Thuringia |

| Self: Affective & Evaluative Facet | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruments | Evaluations | ALF | ALF | F | F | IPSY | IPSY | IPSY | L-Q | R | |||||||||||

| [44] | [35] | [46] T1 | [45] T2 | [53] T1 | [37] | [56] | [54,58] | [36,55] | [59] | [60] | [52] | [47] | |||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | |||||

| Attitude towards alcohol | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Attitude towards cannabis | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Attitudes towards smoking 1 | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Attitude towards smoking 2 | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Expectation regular use: alcohol | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||

| Expectation regular use: tobacco | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| Expected consequence: alcohol | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Expected consequence: drugs | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Expected consequence: smoking | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Perceived positive consequences of smoking | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Proneness to illicit drug use: Cannabis & Ecstasy | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||||||||||||||||

| Readiness to try smoking | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Resistance certainty to refuse a cigarette offer | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Risk perception general | + | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Risk perception personal | + | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Risk perception relative | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Self-concept of appreciation through others | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Self-concept of general self-worth | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Self-esteem 1 | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Self-esteem 2 | ● a | + a | |||||||||||||||||||

| Susceptibility to smoking | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Willingness to quit smoking | ● a | + a | |||||||||||||||||||

| Self: Dispositional & Dynamic Facet | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruments | Evaluations | ALF | ALF | F | F | IPSY | IPSY | IPSY | L-Q | R | |||||||||||

| [44] | [35] | [46] T1 | [45] T2 | [53] T1 | [37] | [56] | [54,58] | [36,55] | [59] | [60] | [52] | [47] | |||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | |||||

| Helplessnes | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Life Skills Deficits | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Life Skills Resources | + | + | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Resistance alcohol | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Resistance cigarette | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||

| Resistance to Peer Pressure | + | ● | ● | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Resisting Peer Pressure | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Self-concept of problem solving skills | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Self-concept of stability against groups | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Self-efficacy 1 | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Self-Efficacy 2 | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Social competence 1 | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Social competence 2 | ● | ++ a | ++ b | ||||||||||||||||||

| Social competence 3 | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco consumption intention | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Self: Cognitive & Descriptive Facet | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruments | Evaluations | ALF | ALF | F | F | IPSY | IPSY | IPSY | L-Q | R | |||||||||||

| [44] | [35] | [46] T1 | [45] T2 | [53] T1 | [37] | [56] | [54,58] | [36,55] | [59] | [60] | [52] | [47] | |||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | |||||

| Social support | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||||

| Number of Validated Instruments/New Designed Instruments | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LSPs | Instr. Used | Significant Results Name of Validated Instrument/Name of New Designed Instrument | |

| ALF | 9/5 | ∙ Life Skills Resources | ----- |

| F&S | 2/4 | ----- | ----- |

| IPSY | 9/4 | ∙ Expectation regular use: tobacco *, ∙ Resistance to Peer Pressure * | ∙ Proneness to illicit drug use: cannabis & ecstasy ∙ Resistance cigarette |

| L-Q | 1/4 | ∙ Self-esteem 2 | ∙ social competence ∙ Willingness to quit smoking |

| Rebound | 0/3 | ----- | ∙ Risk perception: general & personal |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leiblein, T.; Bitzer, E.-M.; Spörhase, U. What Skills Do Addiction-Specific School-Based Life Skills Programs Promote? A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215234

Leiblein T, Bitzer E-M, Spörhase U. What Skills Do Addiction-Specific School-Based Life Skills Programs Promote? A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):15234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215234

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeiblein, Tobias, Eva-Maria Bitzer, and Ulrike Spörhase. 2022. "What Skills Do Addiction-Specific School-Based Life Skills Programs Promote? A Systematic Review" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 15234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215234

APA StyleLeiblein, T., Bitzer, E.-M., & Spörhase, U. (2022). What Skills Do Addiction-Specific School-Based Life Skills Programs Promote? A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 14(22), 15234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215234