Job Crafting and Job Performance: The Mediating Effect of Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Job Crafting

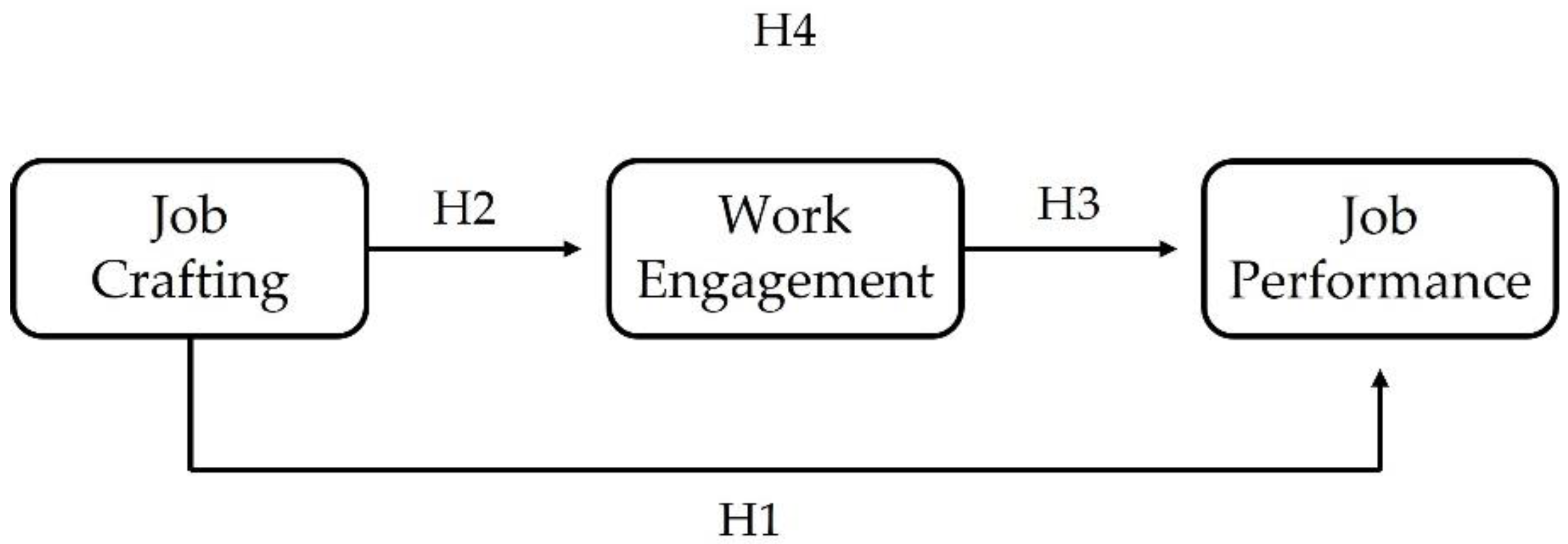

2.2. Job Crafting and Job Performance

2.3. Job Crafting and Work Engagement

2.4. Work Engagement and Job Performance

2.5. Mediating Effect of Work Engagement

3. Method

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

3.4. Instruments

4. Results

Hypothesis Test

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hantula, D. Job satisfaction: The management tool and leadership responsibility. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2015, 35, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.J.; King, L.A. Work and the good life: How work contributes to meaning in life. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.E.; VanderWeele, T.J. Longitudinal meta-analysis of job crafting shows positive association with work engagement. Cogent Psychol. 2020, 7, 1746733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Brummelhuis, L.L. Work engagement, performance, and active learning: The role of conscientiousness. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Wheeler, A.R. The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work. Stress 2008, 22, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Agut, S.; Peiró, J.M. Linking Organizational Resources and Work Engagement to Employee Performance and Customer Loyalty: The Mediation of Service Climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B. A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Marques Pinto, A.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Bakker, A.B., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A. Finding Positive Meaning in Work. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Wrzesniewski, A. Job crafting and meaningful work. In Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace; Dik, B.J., Byrne, Z.S., Steger, M.F., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, T.W.; Dickinson, J.M.; Greene, T.M.; McKibben, E. Self-engagement at work. In Positive Organizational Behavior; Nelson, D.L., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Daily job crafting and the self-efficacy—Performance relationship. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, P.W.; Fischbach, A. Job crafting and motivation to continue working beyond retirement age. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruning, P.F.; Campion, M.A. A role–resource approach–avoidance model of job crafting: A multimethod integration and extension of job crafting theory. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, J.; Tan, F.Y.; Zulkarnain, Z.I.T. Autonomy, workload, worklife balance, and job performance among teachers. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, R.; Yustina, A.I.; Santosa, S. How Work Family Conflict, Work-Life Balance, and Job Performance Connect: Evidence from Auditors in Public Accounting Firms. J. ASET 2020, 12, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M. Type-A behavior in a multinational organization: A study of two countries. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2007, 23, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Factors affecting job performance in public agencies. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2010, 34, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-C.; Silverthorne, C. The impact of locus of control on job stress, job performance and job satisfaction in Taiwan. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgen, D.R.; Hollenbeck, J.R. The structure of work: Job design and roles. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Hough, L.M., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 165–207. [Google Scholar]

- Baard, S.K.; Rench, T.A.; Kozlowski, S.W.J. Performance adaptation: A theoretical integration and review. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 48–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Wrzesniewski, A.M.Y.; Dutton, J.E. Perceiving and responding to challenges in job at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Williams, H.M.; Turner, N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W. The Effects of Job Crafting on Job Performance among Ideological and Political Education Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S.; Kinnunen, U.; Ruokolainen, M. Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 70, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, S.; Yozgat, U. Work–family conflict and job performance: Mediating role of work engagement in healthcare employees. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S. Work engagement: Current trends. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Tamayo, A.M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Episodic demands, resources, and engagement: An experience-sampling study. J. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 16, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. Daily fluctuations in work engagement: An overview and current directions. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W.G. Challenge versus hindrance job demands and well-being: A diary study on the moderating role of job resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 702–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources theory: Taking strock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. Int. J. Adv. Psychol. Theory 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A. Job crafting. In An Introduction to Contemporary Work Psychology; Peeters, M., de Jonge, J., Taris, T.W., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 414–433. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wingerden, J.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A. The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Qiu, X.; Yang, L.; Han, X.; Li, Y. The Relationship Between Work Engagement and Job Performance: Psychological Capital as a Moderating Factor. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 729131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Bal, M.P. Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R.; De Vries, J.D. Job crafting and playful work design: Links with performance during busy and quiet days. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 122, 103478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnlein, P.; Baum, M. Does job crafting always lead to employee well-being and performance? Meta-analytical evidence on the moderating role of societal culture. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 33, 647–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job crafting in changing organizations: Antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, B.T.; Barzin, L.; Vîrgă, D.; Iliescu, D.; Rusu, A. Effectiveness of job crafting interventions: A meta-analysis and utility analysis. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraglia, M.; Cenciotti, R.; Alessandri, G.; Borgogni, L. Translating self-efficacy in job performance over time: The role of job crafting. Hum. Perform. 2017, 30, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral, S.; Geldenhuys, M. The effects of job crafting on subjective well-being amongst South African high school teachers. SA J. Industrial. Psychol. 2016, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, P.; Chen, S. The Impact of Social Factors on Job Crafting: A Meta-Analysis and Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Taris, T. A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hammig, O., Eds.; Springer Science Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; O-Yang, Y. Hotel employee job crafting, burnout, and satisfaction: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd ed.; Atomic Dog Publishing: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL8: Structural Equation Modelling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Hill, A. Investigação por Questionário; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Análise de dados em ciências sociais. In Introdução às Técnicas Utilizando o SPSS Para Windows, 3rd ed.; Celta: Oeiras, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Leonardelli, G.J. Calculation for the Sobel Test: An Interactive Calculation Tool for Mediation Tests [Computer software]. 2001. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkozje))/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=973495 (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Robledo, E.; Zappalà, S.; Topa, G. Job Crafting as a Mediator between Work Engagement and Wellbeing Outcomes: A Time-Lagged Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Nguyen, C.; Ngo, T.T.; Nguyen, L.V. The Effects of Job Crafting on Work Engagement and Work Performance: A Study of Vietnamese Commercial Banks. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letona-Ibañez, O.; Martinez-Rodriguez, S.; Ortiz-Marques, N.; Carrasco, M.; Amillano, A. Job Crafting and Work Engagement: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B. Different types of employee well-being across time and their relationships with job crafting. J. Occup. Health Psych. 2018, 23, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Zamralita, Z.; Lie, D. The Impact of Job Crafting Towards Performance with Work Engagement as a Mediator among High School Teachers in South Tangerang, Indonesia. In Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 3rd Tarumanagara International Conference on the Applications of Social Sciences and Humanities (TICASH 2021); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 655. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devotto, R.P.; Freitas, C.P.P.; Wechsler, S.M. The role of job crafting on the promotion of flow and wellbeing. Rev. De Adm. Mackenzie 2020, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogala, A.; Cieslak, R. Positive Emotions at Work and Job Crafting: Results from Two Prospective Studies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Sousa, M.J.; Cesário, F. Competencies development: The role of organizational commitment and the perception of employability. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhal, A.J.; Arabi, A.; Zaid, M.F.; Norlela, W.I. Relationship between Affective Commitment, Continuance Commitment and Normative Commitment towards Job Performance. J. Sustain. Manag. Stud. 2020, 1, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Soyer, L.; Vakola, M.; Xanthopoulou, D. The effects of a job crafting intervention on the success of an organizational change effort in a blue-collar environment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 374–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Ucbasaran, D.; Zhu, F.; Hirst, G. Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, S120–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viseu, J.; Pinto, P.; Borralha, S.; Jesus, S.N. Exploring the role of personal and job resources in professional satisfaction the case of the hotel sector in Algarve. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 16, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Work engagement interventions can be effective: A systematic review. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E. Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modeling. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | t | p | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing structural job resources | 52.35 *** | <0.001 | 4.39 | 0.56 |

| Decreasing hindering job demands | 0.723 | 0.235 | 3.03 | 0.81 |

| Increasing social job resources | 2.32 * | 0.010 | 3.10 | 0.91 |

| Increasing challenging job demands | 25.24 *** | <0.001 | 3.87 | 0.73 |

| Task performance | 64.70 *** | <0.001 | 4.55 | 0.51 |

| Citizenship performance | 33.10 *** | <0.001 | 4.14 | 0.73 |

| Work engagement | 23.38 *** | <0.001 | 5.24 | 1.13 |

| 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | ||||||

| −0.04 | - | |||||

| 0.17 *** | 0.15 *** | - | ||||

| 0.56 *** | −0.03 | 0.30 *** | - | |||

| 0.44 *** | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.32 *** | - | ||

| 0.35 *** | −0.04 | 0.39 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.30 *** | - | |

| 0.56 *** | −0.01 | 0.23 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.21 *** | - |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | F | p | R2a | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing structural job resources | Task performance | 28.21 *** | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.38 *** | <0.001 |

| Decreasing hindering job demands | −0.01 | 0.947 | ||||

| Increasing social job resources | −0.02 | 0.712 | ||||

| Increasing challenging job demands | 0.11 * | 0.037 | ||||

| Increasing structural job resources | Citizenship performance | 47.13 *** | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.14 ** | 0.002 |

| Decreasing hindering job demands | −0.07 | 0.092 | ||||

| Increasing social job resources | 0.30 *** | <0.001 | ||||

| Increasing challenging job demands | 0.28 *** | <0.001 |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | F | p | R2a | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing structural job resources | Work engagement | 61.82 *** | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.43 *** | <0.001 |

| Decreasing hindering job demands | −0.01 | 0.947 | ||||

| Increasing social job resources | 0.09 * | 0.020 | ||||

| Increasing challenging job demands | 0.20 *** | <0.001 |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | F | p | R2 | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work engagement | Task performance | 37.24 *** | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.28 *** | <0.001 |

| Citizenship performance | 21.55 *** | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.21 *** | <0.001 |

| Independent Variables | Task Performance | Citizenship Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β Step 1 | β Step 2 | β Step 1 | β Step 2 | |

| Increasing structural job resources | 0.44 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.34 *** |

| Work Engagement | 0.05 | 0.02 | ||

| F | 108.10 *** | 54.41 *** | 64.17 *** | 32.13 *** |

| R2a | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| R2 Change | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Independent Variables | Citizenship Performance | |

|---|---|---|

| β Step 1 | β Step 2 | |

| Increasing social job resources | 0.39 *** | 0.36 *** |

| Work Engagement | 0.13 ** | |

| F | 83.00 *** | 46.57 *** |

| R2a | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| R2 Change | 0.02 ** | |

| Independent Variables | Task Performance | Citizenship Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β Step 1 | β Step 2 | β Step 1 | β Step 2 | |

| Increasing challenging job demands | 0.32 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.45 *** |

| Work Engagement | 0.16 ** | 0.01 | ||

| F | 51.33 *** | 31.38 *** | 115.89 *** | 57.82 *** |

| R2a | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| R2 Change | 0.02 ** | 0.001 | ||

| Hypothesis | Decision | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Job crafting establishes a positive association with job performance | Partially supported |

| H2 | Job crafting establishes a positive association with work engagement. | Partially supported |

| H3 | Work engagement establishes a positive association with job performance | Supported |

| H4 | Work engagement mediates the association between job crafting and job performance. | Partially supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreira, A.; Encarnação, T.; Viseu, J.; Sousa, M.J. Job Crafting and Job Performance: The Mediating Effect of Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214909

Moreira A, Encarnação T, Viseu J, Sousa MJ. Job Crafting and Job Performance: The Mediating Effect of Engagement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):14909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214909

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreira, Ana, Tiago Encarnação, João Viseu, and Maria José Sousa. 2022. "Job Crafting and Job Performance: The Mediating Effect of Engagement" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214909

APA StyleMoreira, A., Encarnação, T., Viseu, J., & Sousa, M. J. (2022). Job Crafting and Job Performance: The Mediating Effect of Engagement. Sustainability, 14(22), 14909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214909