Cognitive Dissonance and Public Compliance, and Their Impact on Business Performance in Hotel Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

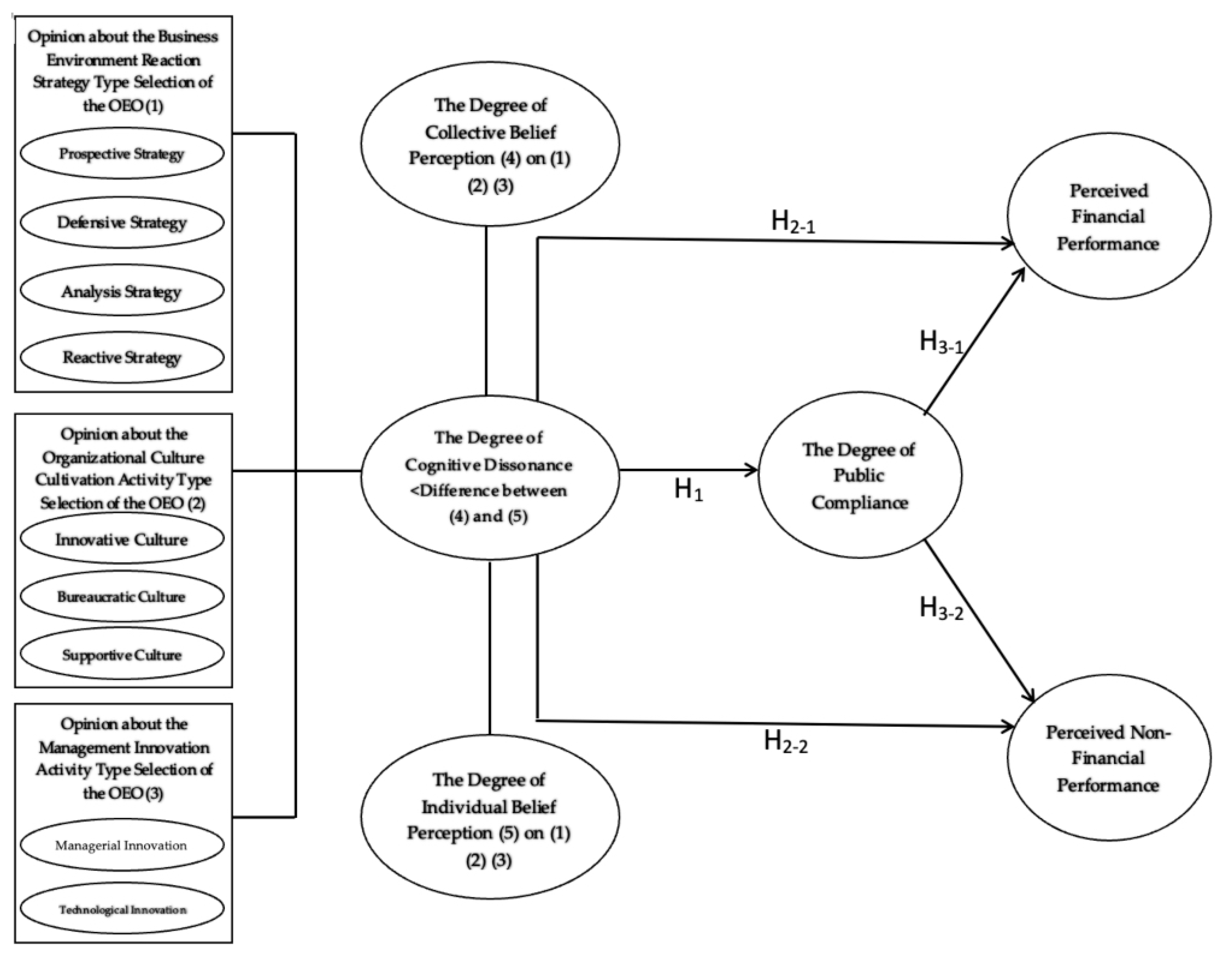

2. Literature Review

2.1. Study on the Cognitive Dissonance in the Service Industry

2.2. Cognitive Dissonance in Business Management

2.3. Cognitive Dissonance and Public Compliance

2.4. Cognitive Dissonance and Public Compliance Affecting Management Performance

2.5. Company’s Business Strategy, Organizational Culture, and Management Innovation Activities

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Variables and Questionnaire Composition

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

4.2. Research Hypothesis Verification Results

4.2.1. Verification of Hypothesis 1

4.2.2. Verification of Hypothesis 2

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weirich, P. Collective Rationality: Equilibrium in Cooperative Games; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Lepine, J.A.; Wesson, M.J. Organizational Behavior: Improving Performance and Commitment in the Workplace; McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dilkashini, V.L.; Kumar, S.M. Cognitive Dissonance: A Psychological Unrest. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Suh, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Hur, T.K. The role of attitude importance in cultural variations of cognitive dissonance. Korean J. Cult. Soc. Issues 2013, 19, 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.G.; Lee, G.H. Structural Relationships among Frontline Hotel Employees’ Core Self-evaluations, Perceived Customer Verbal Aggression and Turnover Intention. Korean J. Culin. Res. 2012, 18, 100–117. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, R.W.; Phillips, J.M.; Gully, S.M. Organizational Behavior: Managing People and Organizations, 13th ed.; Cengage Learning Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, F.W. Scientific Management; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1962; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, R.E.; Snow, C.C. Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. Attitudes and cognitive organization. J. Psychol. 1946, 21, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osgood, C.E.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The principle of congruity in the prediction of attitude change. Psychol. Rev. 1955, 62, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, E.; Akert, R.M.; Wilson, T.D. Sozialpsychologie; Pearson Deutschland GmbH: Hallbergmoos, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bawa, A.; Kansal, P. Cognitive Dissonance and the Marketing of Services: Some Issues. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, M.; Palmer, A. Cognitive Dissonance and the Stability of Service Quality Perceptions. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S. Application of the Cognitive Dissonance Theory to the Service Industry. Serv. Mark. Q. 2011, 32, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Montgomery, R. The Effects of Social Influence and Cognitive Dissonance on Travel Purchase Decisions. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, T.K.; Sarker, S. Cognitive Dissonance Affecting Consumer Buying Decision Making: A study Based on Khulna Metropolitan Area. J. Manag. Res. 2012, 4, 191–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharma, M.K. The impact on consumer buying behavior: Cognitive dissonance. Glob. J. Financ. Manag. 2014, 6, 833–840. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Ok, C.M. Understanding hotel employees’ service sabotage: Emotional labor perspective based on conservation of resources theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. Do job resources moderate the effect of emotional dissonance on burnout? A study in the city of Ankara, Turkey. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Group decision and social change. In Readings in Social Psychology; Swanson, G.E., Newcomb, T.M., Harley, E.L., Eds.; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1952; pp. 459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Demarinis, S.E. An Assessment of the Causes of Cognitive Dissonance in the Working Environment of the Hospitality Industry; MASTER of Science, University of Nevada: Las Vegas, LA, USA, 1994; Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/assessment-causes-cognitive-dissonance-working/docview/304112080/se-2 (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Bashir, A.; Shad, I.; Mumtaz, R.; Tanveer, Z. Organizational ethics and job satisfaction: Evidence from Pakistan. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 2966–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.A.; Lacaze, D. Moderating role of Cognitive Dissonance in the relationship of Islamic work ethics and Job Satisfaction, Turnover Intention and Job Performance. In Proceedings of the 29eme Congress AGRH, 2018, Lyon, France, 29–31 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grebner, S.; Semmer, N.; Faso, L.L.; Gut, S.; Kälin, W.; Elfering, A. Working conditions, well-being, and job-related attitudes among call center agents. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telci, E.E.; Maden, C.; Kantur, D. The theory of cognitive dissonance: A marketing and management perspective. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, J.B.; Miceli, M.P. Potential predictors of whistle-blowing: A prosocial behavior perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirich, P. Does collective rationality entail efficiency? Log. J. IGPL 2009, 18, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovác, L. Science, An essential part of culture. EMBO 2006, 7, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stone, J.; Cooper, J. A self-standards model of cognitive dissonance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 37, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior, South-Western; Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, C.; Fortunato, S.; Loreto, V. Statistical physics of social dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, C.D.; Hinds, P.J. An embedded model of cultural adaptation in global teams. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1056–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, B.; Poncela, J.; Gomez-Gardeñes, J.; Latora, V.; Moreno, Y. Dynamical organization towards consensus in the Axelrod model on complex networks. Phys. Rev. 2010, 81, 056105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanoi, J.; Sayama, H. Post-merger cultural integration from a social network perspective: A computational modeling approach. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2013, 19, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinas, C.; Allan, N.; Johansson, A. Dynamics of organizational culture: Individual beliefs vs. social conformity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180193. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 86, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Chung, G.E. The Study of Relationship between The Person-Organization fit and The Group Cohesiveness of The Mediating Effect of Cognitive Dissonance. Tour. Res. 2014, 39, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, K.W. Tackling the Role Cognitive Dissonance of Public Sector Welfare Professionals: Cause and its Prescription. Korean J. Political Sci. 2012, 20, 289–322. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B.B. The Motivation to Work, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Gawel, J.E. Herzberg’s theory of motivation and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 1996, 5, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, M.H. The effect of electronic communication among franchisees on franchisee compliance. J. Mark. Channels 2003, 10, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.G. Compliance Management for Public, Private, or Non-Profit Organizations; McGraw Hill Professionals: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M.A.; Lassar, W.; Manolis, C.; Prince, M.; Winsor, R.D. A model of trust and compliance in franchise relationships. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Compliance and Public Authority: A Theory with International Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Folan, P.; Browne, J.; Jagdev, H. Performance: Its meaning and content for today’s business research. Comput. Ind. 2007, 58, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A. Business Performance Measurement; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, J.R.; Wally, S. Strategic decision speed and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1107–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.S. Strategic Management; Seoul Economics, and Management: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boyne, G.A. Sources of public service improvement: A critical review and research agenda. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2003, 13, 367–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.I.; Choi, J.G.; Hwang, S.A. The Effects of Strategic Alliance Motivations between Hotel Companies on Alliance Decisive Factors, Operations Conditions, and Business Performance. Korean J. Hotel Adm. 2012, 21, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Daft, R.L. Organization Theory and Design; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kamilah, A.; Shafie, M.Z. The Application of Non-Financial Performance Measurement in Malaysian Manufacturing Firms. In Proceedings of the 7th International Economic & Business Management Conference, Qingdao, China, 15–17 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, C.F.; Yasin, M.M.; Lisboa, J.V. An examination of manufacturing organizations’ performance evaluation; Analysis, implications and a framework for future research. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2004, 24, 488–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.A.; King, M. Factors influencing the alignment of accounting information systems in small and medium-sized Malaysian manufacturing firms. J. Inf. Syst. Small Bus. 2007, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sajilan, S.; Tehseen Sh Yafi, E.; Ting, X. Impact of Facebook Usage on Firm’s Performances among Malaysian Chinese Reatilers. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. 2019, 24, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Stede, W.A.; Chow, C.W.; Lin, T.W. Strategy, choice of performance measures, and performance. Behav. Res. Account. 2006, 18, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, N.H. Relationship of Social Sustainability, Operational Performance and Economic Performance in Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. 2022, 27, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božič, V.; Knežević, C.L. What Really Defines the Performance in Hotel Industry? Managers’ Perspective Using Delphi Method. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2018, 20, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjongwana, A.; Kamala, P.N. Non-Financial performance measurement by small and medium-sized enterprises operating in the hotel industry in the city of Cape Town. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kocmanova, A.; Docekalova, M. Corporate sustainability: Environmental, social, economic and corporate performance. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2011, 59, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerathunga, P.R.; Cheng, X.; Samarathunga, W.H.M.S.; Jayathilake, P.M.B. The Relative Effect of Growth of Economy, Industry Expansion, and Firm-Specific Factors on Corporate Hotel Performance in Sri Lanka. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020914633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatihudin, D. How measuring financial performance? Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. (IJCIET) 2018, 9, 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.G. Hotel General Managers’ Strategic Management Process in Korea and Japan. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2011, 24, 3333–3350. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Yang, Y.; Chung, Y. Effects of Corporate Social Performance on Corporate Financial Performance: A Two-sector Analysis between the U.S. Hospitality and Manufacturing Companies. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. 2018, 23, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Tews, M.J. Emotional Labor: A conceptualization and scale development. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.C.; El’Fred, H.Y. The link between organizational ethics and job satisfaction: A study of managers in Singapore. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechawatanapaisal, D.; Siengthai, S. The impact of cognitive dissonance on learning work behavior. J. Workplace Learn. 2006, 18, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southey, K. A typology of employee explanations of misbehavior: An analysis of unfair dismissal cases. J. Ind. Relat. 2010, 52, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.S.; Choi, S.J.; Park, M.O.; Park, Y.L. The Effects of Customer Service Representatives’ Emotional Labor by Emotional Display Rules on Emotional Dissonance, Emotional exhaustion and Turnover Intention in the Context of Call Centers. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2015, 28, 529–551. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.S.; Ha, J.H. The Causal Relationships Among Emotional Dissonance, Job Burnout, Organizational Commitment, and Counterproductive Work Behavior of Secondary School Physical Education Teacher. J. Coach. Dev. 2017, 19, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.W.; Kwon, K.H. Implementation of synergy: HQ’s choice of intervention modes for resource sharing among SBUs. Korean Manag. Rev. 2012, 41, 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y. The Effects of SMEs’ Collaboration with Large Enterprises on Company Performance: Focusing on Moderating Effect of Entrepreneurship and Market Orientation. Korean Corp. Manag. Rev. 2013, 20, 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, W.Y.; Oh, Y.S. The Impact of Kitchen Employees’ Perception of a Food Purchasing System on Non-Financial Performance in a Contract Food Service Company: Focused on Taegu, Gyeongbuk Area. Korean J. Culin. Res. 2012, 18, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, H.B. The Mediating Effect of the Organizational Citizenship Behavior on the Relationships of the Vision Creation and the Performance. Korea Ind. Econ. Assoc. 2013, 26, 2875–2902. [Google Scholar]

- Zajac, E.J.; Kraatz, M.S.; Bresser, R.K. Modeling the dynamics of strategic fit: A normative approach to strategic change. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simerly, R.L.; Li, M. Environmental dynamism, capital structure and performance: A theoretical integration and an empirical test. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tan, D. Environment–Strategy co-evolution and co-alignment: A staged model of Chinese SOEs under transition. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitabh, M.; Gupta, R.K. Research in strategy–structure–performance construct: Review of trends, paradigms and methodologies. J. Manag. Organ. 2005, 16, 744–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N. Strategic orientation of business enterprises: The construct, dimensionality and measurement. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 942–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasgit, Y.E.; Ergun, E. Corporate Culture and Business Strategy: Which strategies can be applied more easily in which culture? Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Berson, Y.; Oreg, S.H.; Dvir, T. CEO values, organizational culture and firm outcomes J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 29, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P.; Heskett, J.L. Corporate Culture and Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, A.S.; Zhang, Z.X.; Wang, H.; Xin, K.R.; Wu, J.B. Unpacking the relationship between CEO leadership behavior and organizational culture. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Sirmon, D.G. A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 963–989. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K. Management Innovation and Corporate Performance: Moderating Effects of Network Organizations. Doctoral Dissertation, The Graduate School of Pusan National University, Busan, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Damanpour, F. Organizational Innovation: A Meta-Analysis of Effects of Determinants and Moderators. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 555–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.S. Typological characteristics and performance of innovative small firms in Korea. Doctoral Dissertation, KAIST, Daejeon, Korea, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, L.Y.M.; Tse, A.C.B.; Yau, O.H.M.; Lee, J.S.Y.; Chow, R. The effect of relationship marketing orientation on business performance in a service-oriented economy. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 656–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grofcikova, J. Impact of selected determinants of corporate governance of financial performance of companies. Ekon.-Manaz. Spektrum 2020, 14, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schule, M.; Ostroff, C.; Shmulyian, S.; Kinicki, A. Organizational Cliate Configurations: Realtionships to Collective Attitudes, Customer Satisfaction, and Financial Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barendregt, C.; Poel, A.V.D.; Mheen, D.V.D. Trcing Selection Effects in Three Non-Probability Samples. Eur. Addict. Res. 2005, 11, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Division | Frequency (Person) | Ration (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 183 | 49.2 |

| Men | 189 | 50.8 | |

| Ages | 20s | 140 | 37.6 |

| 30s | 163 | 43.8 | |

| 40s | 57 | 15.3 | |

| 50s | 12 | 3.2 | |

| Assigned Hotel | Grand Ambassador Seoul | 47 | 12.6 |

| Lotte Hotel Seoul | 46 | 12.4 | |

| Lotte Hotel World | 44 | 11.8 | |

| JW Marriott Dongdaemun Square Seoul | 45 | 12.1 | |

| Walkerhill | 49 | 13.2 | |

| Intercontinental Seoul COEX | 47 | 12.6 | |

| Conrad Seoul | 46 | 12.4 | |

| Park Hyatt Seoul | 48 | 12.9 | |

| Management Form of the Assigned Hotel | Chain Hotel | 372 | 100.0 |

| Class of the Assigned Hotel | Five-Star Hotel | 372 | 100.0 |

| Work Period | Less than a year | 51 | 13.7 |

| 1~5 years | 165 | 44.4 | |

| 5~10 years | 76 | 20.4 | |

| 10~15 years | 38 | 10.2 | |

| Over 15 years | 42 | 11.3 | |

| Job Grade | Staff (Non managerial) | 252 | 67.7 |

| Assistant manager | 76 | 20.4 | |

| Section Chief | 21 | 5.6 | |

| Conductor | 14 | 3.8 | |

| Director (Team Leader) | 9 | 2.4 | |

| Monthly Salary | 100~200 million Won | 154 | 41.4 |

| 200~300 million Won | 133 | 35.8 | |

| 300~400 million Won | 56 | 15.1 | |

| 400~500 million Won | 19 | 5.1 | |

| Over 500 million Won | 10 | 2.7 | |

| Total | 372 | 100.0 |

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | Beta | ||||

| The Degree of Public Compliance on | (constant) | 3.542 | 0.046 | 77.046 | 0.000 | |

| Business Environment Reaction Strategy Type Selection, Organization Culture Cultivation Activity Type Selection, Management Innovation Activity Type Selection | The Degree of Cognitive Dissonance | 0.136 | 0.086 | 0.082 | 1.581 | 0.115 |

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | Beta | ||||

| (constant) | 3.348 | 0.058 | 57.758 | 0.000 | ||

| Financial Business Performance | The Degree of Cognitive Dissonance | 0.060 | 0.108 | 0.029 | 0.553 | 0.581 |

| R = 0.029, R2 = 0.001, Modified R2 = −0.002, F = 0.305, p = 0.581 | ||||||

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | t | p-Value | |

| B | Standard Error | Beta | ||||

| (constant) | 3.406 | 0.059 | 57.528 | 0.000 | ||

| Non-Financial Business Performance | The Degree of Cognitive Dissonance | 0.122 | 0.111 | 0.057 | 1.106 | 0.270 |

| R = 0.057, R2 = 0.003, modified R2 = 0.001, F = 1.222, p = 0.270 | ||||||

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | Beta | ||||

| (constant) | 1.635 | 0.220 | 7.427 | 0.000 *** | ||

| Financial Business Performance | Degree of Public Compliance on Business Environment Reaction Strategy, Organization Culture Cultivation Activity, and Management Innovation Activity | 0.483 | 0.060 | 0.385 | 7.994 | 0.000 *** |

| R = 0.385, R2 = 0.148, modified R2 = 0.146, F = 63.900, p = 0.000 *** | ||||||

| *** p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | t | p-Value | |

| B | Standard Error | Beta | ||||

| (constant) | 1.555 | 0.222 | 7.007 | 0.000 *** | ||

| Non-Financial Business Performance | Degree of Public Compliance on Business Environment Reaction Strategy, Organization Culture Cultivation Activity, and Management Innovation Activity | 0.528 | 0.061 | 0.411 | 8.675 | 0.000 *** |

| R = 0.411, R2 = 0.169, modified R2 = 0.167, F = 75.250, p = 0.000 *** | ||||||

| *** p < 0.001 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xi, W.; Baymuminova, N.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Xu, S.-N. Cognitive Dissonance and Public Compliance, and Their Impact on Business Performance in Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214907

Xi W, Baymuminova N, Zhang Y-W, Xu S-N. Cognitive Dissonance and Public Compliance, and Their Impact on Business Performance in Hotel Industry. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):14907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214907

Chicago/Turabian StyleXi, Wen, Nigora Baymuminova, Yi-Wei Zhang, and Shi-Nyu Xu. 2022. "Cognitive Dissonance and Public Compliance, and Their Impact on Business Performance in Hotel Industry" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214907

APA StyleXi, W., Baymuminova, N., Zhang, Y.-W., & Xu, S.-N. (2022). Cognitive Dissonance and Public Compliance, and Their Impact on Business Performance in Hotel Industry. Sustainability, 14(22), 14907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214907