Abstract

Mobile commerce is a fast-growing industry expected to grow continuously thanks to the wide acceptance of mobile phones and the worldwide 4G infrastructure. Previous research on m-commerce mostly focused on theory, technology acceptance, and legal issues, while service failure and recovery in m-commerce have not yet been covered. However, service failure is inevitable as the service process is complicated, and successful service recovery can retain customers. This research adopts an experimental study to discover the relationship between service failure, service recovery strategy, perceived justice, and post-recovery satisfaction in mobile commerce. The results confirm that, for different types of service failure, the effect of satisfaction level would differ for a different recovery strategy. Moreover, perceived justice would be affected by the service failure magnitude and service recovery strategy and would further affect post-recovery satisfaction. This study will provide an essential reference for both academicians and professionals to conduct further empirical validation or develop appropriate programs to solve service recovery issues.

1. Introduction

Smart-phones have become one of the necessities for people nowadays and highly impact the lifestyle of people, including how they shop. Mobile commerce (or m-commerce) is one of the areas that is growing the fastest. Mobile commerce is the transaction (buying/selling) of tangible goods or intangible services through mobile devices via wireless networks [1]. According to Insider, retail m-commerce sales reached USD 359.32 billion in 2021, which is an increase of 15.2% over 2020. It is also expected that, by 2025, retail m-commerce sales will double to reach USD 728.28 billion and account for 44.2% of retail e-commerce sales in the US. Many e-commerce players, such as Amazon, Taobao, Alibaba, and Shopee, have introduced mobile applications and encouraged their customers to transfer to their m-commerce platforms [2]. Some reservation platforms for ticketing, such as Taiwan High-Speed Railway, Airbnb, and Eventbrite, also provide a dedicated mobile application so that booking can occur with a few simple clicks. With the recent rise in mobile payments, such as Apple Pay, Google Wallet, and Samsung Pay, the ease of access to m-commerce is gradually increasing. It is expected that the importance of m-commerce will increase continuously and will be widely accepted by the public shortly.

Previous research on m-commerce mostly focused on theory (conceptualisations, unique value and propositions, distinctions from e-commerce, state-of-the-art reviews) [3], strategy (marketing strategies, marketing tools) [4], and consumer behaviour (acceptance and adoption, role of trust, satisfaction and loyalty, attitude, perceived value, and value creation) [2,5]. Surprisingly, the topic of service failure and recovery on m-commerce is still being neglected. However, service failure is inevitable as the service process is very complicated; thus, successful service recovery can fix mistakes and win customers back [6]. Especially when m-commerce is still growing and many people have just started to accept this technology, it is critical to solve service failure issues to regain customer satisfaction properly.

For any kind of service provided, service failure is inevitable due to the complexity of the service process [6]. Although it is unlikely to eliminate all service failures, it is possible for a service provider to recover the service failure in order to retain the customer. When the service recovery is highly accepted by the customer, the satisfaction level from the customer can actually be higher than that of customers not experiencing any problems in the transaction, which is defined as service paradox [7]. However, if customers experience a failure recovery attempt, they are more likely to be driven away due to the enhanced dissatisfaction through two failures, which is stated as a double deviation [8,9]. It is important to note that the cost of obtaining a new customer compared to the cost of retaining an original customer is five times more; thus, maintaining a customer is more important than gaining new customers [10].

Even though the importance of proper service recovery was highlighted, surprisingly, many customers were still unsatisfied with the service recovery they received. Especially for mobile service, in which the interaction is conducted in a virtual environment, the gap between the expectancy and the actual good may lead to dissatisfaction as the goods cannot be felt and seen in advance. At the same time, the lead time for goods received will be longer, and damages may take place in the transit process [8]. These anxieties may lead to increased dissatisfaction should the service failure occur in such a service process. Improvements are still available for service providers to offer service recovery to enhance customer satisfaction and thus retain customers.

Many scholars have researched service failure and recovery strategies in offline channels [8,11] and online channels [12,13]. Thus far, service failure in the mobile context has not yet been conducted. Moreover, it is essential to note that only a few studies have tried to study the effectiveness of service recovery strategies against different service types. Smith et al. [11] proposed a model that proposed four different service recovery strategies (compensation, response speed, apology, initiation) against two types of service failures (outcome, process) and tested it in the catering and hospitality industry. Liu et al. [14] used CIT not only to categorise service failure and recovery typology in the catering industry but further analysed the correspondence between them and determined that the type of recovery strategy used has important differential effects on the recovery rating for different failure typologies. This research aims to fill the research gap of service failure/recovery in mobile commerce and its correspondence and identify an effective recovery strategy for different typologies of service failure. As a result of this study, proper recovery strategies for possible m-commerce service failures will be identified. This study also provides helpful management tools for service providers providing m-commerce or about to enter m-commerce as it can maximise the increase in satisfaction of the customers.

On the other hand, service failure can be viewed as an injustice that the customer perceives/receives, while resolving a customer complaint can be viewed as a series of consecutive events, including the procedure, the communication, and the compensation. Every part will be subjectively evaluated and justice will be restored when customers subjectively feel that they have been equitably treated in the process [7]. Perceived justice can explain the relationship between service failure, service recovery, and post-recovery satisfaction [9,10,15]. According to social exchange theory, the typology and magnitude of service failure will become a reference point from which the customer will judge perceived fairness and procedural and interactional justice during the recovery process, and distributive justice is perceived after the outcome of the recovery [11]. In the previous studies of service failure, regardless of whether they are online or offline, many of them have adopted a three-dimensional view that includes distributive, procedural, and interactional justice [9,12]. It is one of the most widely adopted theories in the previous research of the service recovery model.

According to Goh et al. (2015), mobile shopping is an extension of online shopping. From the research of Bang et al. [2] and Kim et al. [5], it can be concluded that online shopping behaviour and experience are positively related to mobile shopping behaviour and experience. It has been observed from considerable online service failure research that perceived justice is adopted to discuss the relationship between recovery effectiveness and satisfaction level [10,15,16]. As m-commerce service failure has not yet been studied per the authors’ best knowledge, this study aims to leverage the previous studies and use perceived justice to test the satisfactory level of service failure typology, magnitude, and effective service recovery strategy.

This research focuses on studying the relationship between service failure magnitude, service recovery strategy, perceived justice, and post-recovery satisfaction in the context of mobile commerce. This research aims to answer the following research question based on the research motivation: what are the influences of service failure and service recovery strategy on perceived justice and post-recovery satisfaction in the context of mobile commerce?

2. Literature Reviews

2.1. Service Failure

Service encounter is a customer interaction process with the service provider [17]. During a service encounter, service failure occurs when the customer fails to perceive the experience as expected [18]. A service’s nature is inseparable and intangible, so it is difficult for providers to provide “zero-defect” services [19]. As service failure is inevitable, and potential business loss may occur if it is not taken good care of, there has been much research on service failure since 1980. Mainly, scholars discuss service failures of the offline channel from different perspectives, such as service quality, expectancy disconfirmation, or justice theory.

Many scholars have defined service failure in their research. Smith et al. [11] regarded service failure as a loss in which customers would have to bear extra costs, such as the loss of economic (e.g., money, time) or social resources (e.g., status, esteem). Lewis and Spyrakopoulos [20] considered from the customer’s perspective that, whatever the source of the failure is, service failure is the unsatisfied or problematic situation regarding the delivered service or the service provider. Maxham [6] defined service failures as any service-related issues (actual and/or perceived) that occurred during a consumer’s interaction with a firm. It can be concluded that the customer, instead of the service provider, defines service failure. If the customer regards service to fail its expectation, then the customer would define it as a service failure regardless of whether the service provider really “fails” to provide the service from the service provider’s point of view. Even if the service provider fails to provide service that meets the customer’s expectation, so long as the service provided is not regarded by the customer as a “service failure”, it is not counted as a service failure [21].

2.2. Service Failure Magnitude

The service failure magnitude, or severity, is defined as the level of loss customers feel from a failure [22] or the perceived severity of the service failure [20]. Previous research results indicated that, the higher the failure magnitude, the lower the customer satisfaction level and the increased expectations for service recovery [23]. Xu et al. [24] demonstrated that the magnitude of the failure has a positive effect on customers’ negative emotions, such as upset, frustration, and anger. Bakhare [25] also found that, the more significant the loss caused by the service failure, the less equitable the customer would perceive the service (exchange) process, and the more effort is required to restore equity. The cost to a customer for a severe service failure increases significantly [26]. Previous research has also identified failure severity as a critical factor affecting service failures and recoveries [18,27].

Both prospect theory and mental accounting theory suggest that loss from service failure will be weighted more heavily in service failure compared with gain [11]. For the same type of failure, the higher the failure magnitude, the higher the recovery level required to compensate for the loss of a customer [15]. Thus, even with a proper service recovery process after a service failure, the high magnitude of failure will still produce a perceived loss for customers. From the above literature review, it can be stated that service failure magnitude is a crucial part of service failure as it positively affects customer satisfaction and the level of recovery required.

2.3. Service Recovery Strategy

Although service firms cannot eliminate every service failure due to the complexity of the service process, firms can respond effectively to failures once they occur [6]. Xu et al. [24] defined service recovery as an action by a firm to eliminate the negative collision of a failure. Blodgett et al. [17] stated that service recovery is a resolution to overcome satisfactory problems. Migacz et al. [28] described service recovery as the design to resolve problems, alter the negative attitudes of unhappy customers, and retain the customers eventually. From previous research, successful service recovery can lead to higher post-recovery satisfaction, a critical antecedent towards customer loyalty and positive word-of-mouth [29]. Borah et al. [30] further stated that, if the customer has faced unsatisfactory service recovery after a service failure, the unsatisfactory level will increase, eventually leading to a customer switch. Service recovery effectiveness has a positive relationship regarding a firm’s survival and growth, so its importance cannot be overlooked [31].

Several scholars have established various service recovery strategies. From the corporate perspective, Davidow [32] proposed six recovery strategies when facing customer complaints: apologise, timely, remedy, credible, facilitate, and attentive. Aside from the perspective of corporation or customer, service recovery activities can also be categorised by recovery actions. Kuo et al. [33] surveyed Taiwan’s online auction service recovery. They categorised eight recovery strategies from the online retailers: discount, correction, correction plus, apology, refund, store credit, replace via the offline channel, and replace via the original online channel. Recently, Kaur et al. [34] explained that providing opportunities for customers to express themselves is also effective and suggested three recovery strategies: apology, compensation, and voice.

One of the most commonly adopted service recovery strategies is tangibility. Chuang et al. [35] have proposed two recovery strategies: tangible and psychological. Tangible recovery focuses on compensating for actual and perceived damages, including standard techniques, such as free-of-charge, free samples, coupons, or other monetary-level compensations. However, psychological recovery shows concern for customer needs and reduces customers’ physical discontent. Empathising, apologising, correcting, and in-time responses are some recommended techniques

2.4. Perceived Justice

Huppertz et al. [36] were the first to adopt the justice theory in marketing research. In their study, customers would compare what they have spent to what they have received, and only when their perceived value is equal to the price can they receive perceived justice. Various researchers agreed that justice theory would explain the relationship between service failure, service recovery, and post-recovery. Resolving customer complaints is a series of consecutive events, including the procedure, the interaction, and the remedy, and every part will be subjectively evaluated. When customers subjectively feel that they have been treated equitably, justice will be restored [8].

Justice theory has several factors on which scholars have different views. Previous research considers only distributive and procedural justice [37]. At the same time, others have adopted a three-dimensional theory that includes distributive, procedural, and interactional justice [16]. The three-dimensional view is the most widely adopted in the previous research on the service recovery model. Customers evaluate perceived fairness by evaluating three factors: distributive justice (resource allocation and perceived outcome of exchange), procedural equity (the fairness of the recovery policy/procedure), and interaction (the politeness and empathy shown in the recovery process) [38]. It is evident from many online service failure studies that justice theory is adopted to discuss the relationship between recovery effectiveness and satisfaction level [8]. As m-commerce can be seen as an extension of e-commerce, it is critical to examine the role of perceived justice to understand customer satisfaction [25].

2.5. Post-Recovery Satisfaction

Customer satisfaction is the subjective evaluation of an outcome/experience’s favourability [11]. Based on Kuo et al. [33] ‘s view, satisfaction is an outcome of the transaction-specific result; customers conceptually compare rewards and costs with anticipated consequences. Customer satisfaction is important to firms for its influence on retention and loyalty [8]. According to Hirschman’s [39] exit-voice theory, once customer satisfaction has been raised, the immediate consequence is a decrease in customer complaints and an increase in customer loyalty [40]. Understandably, customers are more willing to stay with service providers who can offer satisfactory service than those who cannot.

To distinguish satisfaction after service recovery from satisfaction after service, scholars have defined satisfaction after service recovery from the service provider as “post-recovery satisfaction” from the initial satisfaction. It is defined as the satisfactory level of a service provider’s second (recovery) service after experiencing service failure [16,41]. As this research focuses on examining the post-recovery satisfaction level on a specific service encounter, in line with the prior research, the post-recovery satisfaction level is valued based on the satisfaction level of customers with the service firm’s service recovery effort after a service failure.

2.6. The Relationship between Service Failure, Service Recovery Strategy, and Post-Recovery Satisfaction

Service failure can be viewed as the injustice customers perceive/receive, while resolving customer complaints can be viewed as a series of consecutive events, including the procedure, the communication, and the compensation. Every part will be subjectively evaluated, and justice will be restored when customers believe they have been treated equitably in the process [41]. Perceived justice can explain the relationship between service failure, service recovery, and post-recovery satisfaction [38]. According to social exchange theory, the typology and magnitude of service failure will become a reference point through which customers will judge the perceived fairness, procedural, and interactional justice during the recovery process, and distributive justice is perceived after the outcome of the recovery [11].

According to Jain et al. [42], mobile shopping is an extension of online shopping. Kim et al. [5] concluded that online shopping behaviour and experience positively relate to mobile shopping behaviour and experience. It is evident from many online service failure studies that perceived justice is adopted to discuss the relationship between recovery effectiveness and satisfaction level [9]. As m-commerce service failure has not yet been studied to the authors’ best knowledge, this study would like to leverage the previous studies and use perceived justice to test the satisfaction level of service failure typology, magnitude, and the affective service recovery strategy.

Previous researchers have identified failure severity as a critical factor affecting service failures and recoveries [18,27]. As the level of loss becomes higher due to the service failure, according to the principles of resource exchange, the more dissatisfied and inequitable the customers would be. In line with previous studies [11,19], this research will take the magnitude of service failure as an essential factor and test its effect on perceived justice.

H1.

The magnitude of service failure significantly affects perceived justice.

H1a.

The magnitude of service failure significantly affects distributive justice.

H1b.

The magnitude of service failure significantly affects procedural justice.

H1c.

The magnitude of service failure significantly affects interactional justice.

From the viewpoint of social exchange and equity theory, service recovery can be viewed as an exchange of service providers to provide a gain for a customer’s loss due to service failure [43]. Albrecht et al.’s research [44] is based on equity theory and determined that customers’ perceived fairness will be affected by the level of compensation received. In Jung and Seock’s study [12] on online shopping, it is also proven that different types of service recovery will change the customer’s perception of perceived justice, and the relationship is significant. Arasli et al. [45] also consider service recovery to be an exchange behaviour of social and economic resources between the customer and service provider.

For how the service recovery strategy affects perceived justice, Smith et al. [11] concluded from their research that distributive justice will be positively affected by compensation, procedural justice will be positively affected by the response, and interactional justice will be positively affected by an apology and the initiation of the service provider. The hypothesis based on the above literature is proposed as follows.

H2.

Service recovery strategy significantly affects perceived justice.

H2a.

Service recovery strategy significantly affects distributive justice.

H2b.

Service recovery strategy significantly affects procedural justice.

H2c.

Service recovery strategy significantly affects interactional justice.

Many studies have tested the relationship between perceived justice and post-recovery satisfaction. They confirmed that distributive justice [44,46], procedural justice [11,41], and interactional justice [37,46] have a significant relationship towards post-recovery satisfaction. Research has also shown that sufficient information provided to customers helps them understand the situation and can be treated as compensation [13]. Smith et al. [11] also concluded that recovery attributes would not affect post-recovery satisfaction. Instead, it will be mediated by expectancy-disconfirmation and perceived justice; moreover, organisations should include managing relationships with customers’ perceived justice instead of focusing on expectation disconfirmation only. Ali et al. [47] further stated that customers evaluate the service encounter and verify its satisfaction level from several dimensions: outcome (benefits customers received), procedure (the organisation’s policy and the method towards the service encounter), and interaction (the quality of communication during the encounter). With the above support, the hypotheses were proposed as follows:

H3.

Perceived justice significantly affects post-recovery satisfaction.

H3a.

Distributive justice significantly affects post-recovery satisfaction.

H3b.

Procedural justice significantly affects post-recovery satisfaction.

H3c.

Interactional justice significantly affects post-recovery satisfaction.

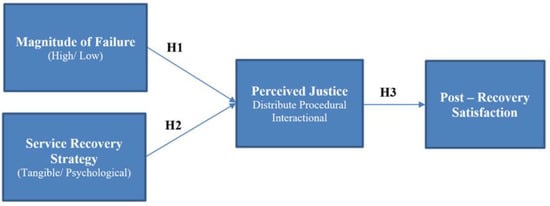

Based on the literature review and in-depth interview results, this study developed a research framework as shown in Figure 1. There are four major constructs.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Research Design: Experimental Design

To respond to the research question, a 2 × 3 experimental design was used to examine the influence of service failure and service recovery strategy on perceived justice and post-recovery satisfaction. Many scholars have used the scenario-based experimental design in previous service failure studies [6,13,48]. With the scenario-based experimental design, the participants can immerse themselves in the situation by reading the designed scenario and providing valuable feedback to the research.

The independent variables were magnitude of failure (high/low) and service recovery strategy (tangible/psychological/tangible + psychological). Six scenarios were developed to measure the dependent variables: perceived justice (distributive/procedural/interactional) and post-recovery satisfaction. The scenarios were distributed randomly, and all respondents were given the same questionnaire after reading the given scenario.

The respondents were exposed to the scenario that they had just moved to a new house and needed to buy some tableware for the upcoming housewarming party. A mobile shopping app placed the order for some porcelain plates they liked. The reason for choosing tableware in this experimental design is that it is a neutral product and would not be affected by gender preference, such as 3C products and clothes. Moreover, the shopping app was not explicitly named as the author did not want the brand of the shopping app to affect the respondent’s expectations.

In the scenario, if the respondents were assigned to “high magnitude of failure,” the scenario would be that they had received inferior-quality plates, and some were even broken. On the other hand, the “low magnitude of failure” means the packaging of the goods would be slightly damaged, but the goods were in good shape. For the recovery, if it is a “tangible” recovery, the customer service of the shopping app would provide a refund or return option and a coupon, which are the standard methods mentioned. For “psychological” recovery, the customer service would apologise immediately to the customer with a detailed explanation, which would refer to the in-time and active response from the psychological recovery this study has discovered in CIT. For “tangible + psychological” recovery, the scenario is designed so that the customer would receive all the above recovery options mentioned (See Appendix A).

3.2. Construct Measurements

To examine the hypotheses, the following two constructs were measured in this study: perceived justice and post-recovery satisfaction. The perceived justice construct consists of three factors: distributive justice (5 items modified from Smith et al. [11] and Maxham III and Netemeyer [7]), procedural justice (5 items modified from Blodgett et al. [17] and Smith et al. [11]), and interactional justice (4 items modified from Smith et al. [11] and Maxham III and Netemeyer [7]). Finally, the post-recovery satisfaction construct was measured with five items modified from Smith et al. [11] and Maxham III and Netemeyer [7]. Each measurement was measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree” (See Appendix B).

3.3. Sampling Process

The data were collected through a web-based questionnaire from a convenience sample of users. The scenario-based experimental study was performed via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a crowdsourcing internet space that allows people in need to place a request on the system and volunteered respondents, or so-called “workers”, to complete the task for a certain amount of monetary payment provided by the employers. The official experiment was conducted from October 2021 to November 2021. This study received a total of 250 responses. Twelve responses were invalid as the answers provided were too consistent. Thus, there are a total of 238 valid responses. The valid rate of response is 95.2%. Table 1 shows the composite of the responses from each scenario.

Table 1.

Composition of sample for the experiment.

Of 238 respondents, 143 were male (60%), and most were aged between 26 and 35 (56%). Most respondents hold a bachelor’s degree (58%) with 3–5 years of experience using m-commerce (44%). The average frequency of using mobile commerce is most commonly once a week (26%), once a month (26%), and twice a week (19%). One thing worth noting is that 75% of the respondents have previous experience with mobile commerce failures. It is a common issue, and it is worthwhile to investigate how to decrease such failure. Detailed information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive information of sample for the experiment.

3.4. Data Analysis Procedures

Statistical software SPSS 18.0 was adopted as the analytical tool to run the data analysis. Various tests were performed to verify the hypotheses. (1) Factor analysis and reliability analysis were performed to confirm the fit of the hypothesized factor structure to the observed data. At the same time, factor analysis was used to explore the underlying variance structure of a set of correlation coefficients. (2) Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to test the relationship of service failure magnitude service failure strategy against perceived justice. (3) Multiple regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between perceived justice and post-recovery satisfaction.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Factor Analysis and Reliability Test

This study conducted a factor analysis and reliability test to ensure the dimensions and reliability of the research constructs. Table 3 shows that most of the factor loadings of all the questionnaire items are higher than 0.6, the Eigenvalues of all the factors are higher than 1, the cumulative explained variance values of all the factors are higher than 60%, the item-to-total correlation coefficients are higher than 0.5, and all the Cronbach’s alpha values are higher than 0.8. All the numbers here exceed the generally accepted guidelines from Hair et al. [49]. Therefore, all the questionnaire items show high internal consistency, and their factors are appropriate for further analysis. Detailed results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of factor analysis and reliability test.

4.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model: Hypotheses Testing

4.2.1. Relationship between Service Failure Magnitude, Service Recovery Strategy, and Perceived Justice

In this section, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to test the relationship between service failure magnitude, service recovery strategy, and perceived justice. The results are shown in Table 4. For the effect of service failure magnitude on perceived justice, all the relationships are confirmed with distributive justice (F = 14.146, p < 0.001), procedural justice (F = 11.640, p < 0.001), and interactional justice (F = 8.489, p < 0.01). Therefore, H1a, H1b, and H1c are all supported statistically.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance of perceived justice rating by service failure magnitude and service recovery strategy.

For the effect of service recovery strategy on perceived justice, the influences of distributive justice (F = 25.178, p < 0.001), procedural justice (F = 34.297, p < 0.001), and interactional justice (F = 23.568, p < 0.001) are all significant. Thus H2a, H2b, and H2c are confirmed.

Table 4 shows that the interaction effects of service failure magnitude and service recovery strategy are only significant on distributive justice (F = 4.600, p < 0.05) and procedural justice (F = 45.203, p < 0.01). For interactional justice, the interaction effects are not significant.

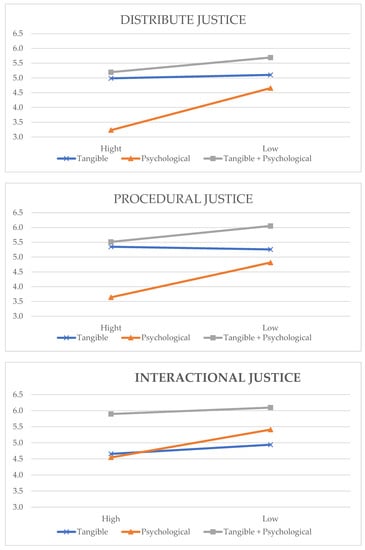

Table 5 and Figure 2 show how perceived justice’s mean value differs from the effects of service failure magnitude and service recovery strategy. For distributive justice, the overall mean value is higher for low magnitude compared to the high magnitude of failure. Overall, tangible + psychological obtains the highest mean value, followed by tangible recovery, and the lowest psychological recovery. As distributive justice is relevant to perceived equity and equality, the results confirm that lower severity of the failure can lead to a higher level of distributive justice. Similarly, tangible recovery is more effective than psychological recovery on perceived distributive justice.

Table 5.

Descriptive analysis for service failure magnitude, service recovery strategy, and perceived justice.

Figure 2.

The interaction effect between service failure magnitude, service recovery strategy, and perceived justice (vertical: mean value).

For procedural justice, the outcome is similar to distributive justice except for a tangible recovery strategy. From Figure 2, perceived procedural justice is slightly higher when the failure magnitude is high than when the failure magnitude is low. To interpret, procedural justice is based on timeliness and recovery policy fairness; when the failure magnitude is low, tangible recovery cannot address the timeliness and policy fairness respondents expect.

For interactional justice, as it is evaluated by perceived politeness, effort, and empathy, unlike distributive and procedural justice, psychological recovery has surpassed tangible recovery. It obtains higher perceived interactional justice, especially in the low failure magnitude. This result adds to the previous research result. It shows that interactional justice is more affected by psychological recovery, while a robust understanding previously was that tangible recovery would result in higher justice in all aspects.

The above results are an enhancement of previous research. In line with the study of Nikbin and Hyun [19], severity level affects perceived justice. Dissatisfaction and the feeling of injustice under the condition of high severity are higher than under low severity. McQuilken et al.’s study [27] also shows that, under a severe failure event, compensation following the customer’s expectation or previous promise is more appreciated; higher injustice due to a higher level of service failure would require a higher level of recovery to restore equity. The service recovery strategy is also in line with Jung and Seock’s study [12] on online shopping, in which different types of service recovery will change the customer’s perception of perceived justice, and the relationship is significant.

In the context of mobile commerce, this research further contributes to the service recovery studies on how service failure magnitude and service recovery strategy affect perceived justice. The level of perceived justice is higher when the magnitude of failure is lower. Tangible recovery is more effective than psychological recovery on perceived distributive and procedural justice, while psychological recovery results in higher perceived interactional justice than tangible recovery.

4.2.2. Relationship between Perceived Justice and Post-Recovery Satisfaction

To examine the relationship between perceived justice and post-recovery satisfaction, multiple regression is used. The threshold adopted to verify the regression result is: R2 > 0.1, F-value > 4, p-value < 0.05, D-W between 1.5~2.5, and VIF < 3. For the experiment set of outcome failure, the R2 value, F-value, and p-value all meet the threshold from model 1 to model 3 and the overall model. This result indicates that distributive justice and procedural justice significantly affect post-recovery satisfaction. From this, H3a, H3b, and H3c are supported. Detailed results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Regression analysis results of perceived justice and post-recovery satisfaction.

From Table 6, it can be noted that procedural justice has the highest beta value in both the individual and the overall model, followed by distributive justice and interactional justice. Procedural justice has the highest effect on post-recovery satisfaction. This result differs from some previous service recovery studies offline [8,10] and online [50] in which distributive justice has the highest effect compared with perceived justice. As our study is on mobile commerce, which in nature has the characteristic of “always online” and “24/7 access”, from the result, it can be stated that the importance of in-time response has surpassed the importance of the other factors. The study from Crisafulli and Singh [51] also stated that recovery response time is significant and can highly affect customer satisfaction.

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

5.1. Research Conclusion

Several research conclusions could be drawn from the empirical results of this study: first, for outcome failure, tangible recovery is preferred, and, for process failure, psychological recovery is preferred. In line with resource exchange theory, when a customer suffers from a failure leading to a dissatisfied outcome, a tangible good is preferred as a recovery mediate. A psychological recovery can be a plus on top of the tangible goods; however, the customers will not perceive the recovery by only providing the psychological recovery. The same goes for process failure: even if the outcome is what the customer expected, the process’s flaws are already psychologically causing dissatisfaction. An absence of recovery in this regard would drive customers away.

Second, this study has determined that service failure magnitude and service recovery strategy have a significant effect on perceived justice. Explained by the social exchange principle and mental accounting principle, the level of perceived justice is higher when the magnitude of failure is lower. Furthermore, the lower level of service failure severity and tangible + psychological recovery result in a higher level of justice. For distributive and procedural justice, tangible recovery results in a higher level of justice; for interactional justice, psychological results in a higher level of justice, especially in low severity. The above results serve to enhance the previous research in service failure and recovery [11,19,27].

Finally, service failure magnitude and service recovery strategy significantly influence perceived justice. Moreover, perceived justice significantly affects post-recovery satisfaction, especially procedural justice, which has a higher effect on post-recovery satisfaction. What is found in this study specifically is that, as this study is conducted in the context of mobile commerce, procedural justice has the highest effect, followed by distributive justice and interactional justice. Crisafulli and Singh [51] also stated that the situational factors and the recovery effort from the firm will affect the customer’s perceptions of response time, and, in general, a short response time leads to higher customer satisfaction. Furthermore, the study also differs from previous studies for offline [27,52] and online [37] service recovery in which distributive justice has the strongest effect.

5.2. Academic Contribution

There are two significant academic contributions of this study. The first one involves closing the research gap in m-commerce service failure and recovery. Previous studies on mobile commerce are mostly on intention and motivation [53,54], technology acceptance [3,55], and mobile marketing consumer reaction/attitude [4,56]. As for service failure and recovery, the previous studies focus on either offline [8,11,25] or online [12,51]. The topic of service failure and recovery in m-commerce has not yet been covered. This study has addressed this research gap and leveraged the previously used concept for offline and online service failure studies onto mobile commerce service failure.

The second contribution is a complete model of service failure. For service failure and recovery, many studies have only covered how justice affects post-recovery satisfaction [8,38] or discussed the relationship between service failure and recovery [35]. This study has combined the studies by Liu et al. [14] and Smith et al. [11] and proposed a complete model of service failure typology, magnitude, service recovery strategy, perceived justice, and post-recovery satisfaction. For the relationship between service recovery strategy, service failure typology, and post-recovery satisfaction, this study has used resource exchange theory to explain which recovery strategy can best recover the failure and increase customer satisfaction. Prospect theory and mental accounting principles explain how service failure typology and magnitude affect perceived justice. Finally, social exchange theory explains how service recovery restores perceived justice and how perceived justice enhances post-recovery satisfaction. The model presented in this study has introduced a complete understanding of service failure and recovery in the context of mobile commerce.

5.3. Managerial Implication

According to the GSMA’s 2022 Mobile Economy Report, 5.2 billion people, around two-thirds of the world’s total population, have subscribed to mobile services. It can be foreseen that many people will be stepping into the m-commerce field. This study has provided three managerial implications as follows.

The first implication is that, for service providers in mobile commerce, appropriate service recovery should be provided according to the service failure magnitude. Of course, the best method of recovery is to provide as much compensation as possible. However, as the resources for each service provider are limited, what kind of recovery can satisfy the customer most effectively? Research has demonstrated that, for different types of failure, customers would expect different types of recovery, and satisfaction with recovery that meets their requirements would score the highest. It is suggested that, when a service failure occurs, the service provider should first identify the typology of the failure and how severe it is. Then, a most effective solution should be provided accordingly. This study has proven that tangible recovery can recover outcome failure better, and psychological recovery can recover process failure better.

The second implication is the timeliness factor of m-commerce. The results of this study show that in-time response is highly crucial, affecting both perceived justice (procedural justice) and post-recovery satisfaction. As wireless mobile devices decrease the difficulties of access, this not only increases the willingness of people to purchase through mobile devices but also dramatically changes how service providers interact and deliver service to customers [51]. Wireless mobile technology also eliminates the time boundaries between traditional retail and brick-and-mortar services [57]. When establishing customer service, timeliness is a critical point to consider for service providers currently offering or about to offer service in m-commerce.

The third implication is system and interface management. Many respondents mentioned during the CIT interview that, when using m-commerce, one of the main issues they have faced is that it is difficult for them to find the things they need, or they have faced system error issues. Previous research on technology acceptance has proven that mobile devices are more likely to be used for task-oriented behaviour. In contrast, PC devices are used for more exploration-oriented browsing behaviour [58]. When people cannot access a service or face difficulty when using the service, this is accounted as a specific type of service failure. However, it is essential to note that, for such service failure, most people will not claim for recovery; they would just transfer to another service provider or even return to an online or offline channel. As customer–service provider interactions are mediated by technology [59], this study suggests that m-commerce service providers conduct regular customer satisfaction surveys on the goods customers receive and how customers feel about their interface and system design for continuous enhancement.

Finally, this study reminds service providers in mobile commerce that post-sale service is quite important to maintain customer loyalty. In a mobile commerce market where service failure is subjective to the expectations and perceptions of the customers, activity regarding service recovery will decrease damage and retain customers. In a positive service failure situation, a service recovery action might even increase a customer’s satisfaction more than in a service success situation. It will help service providers in developing their brand and aim for sustainable development [60].

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Suggestions

Although this research has tried to discuss the relationship between service failure, service recovery, perceived justice, and post-recovery satisfaction in the context of mobile commerce, due to the limited resources available, there are some perspectives that this research has not yet covered completely. The first limitation is that the limited sample in this research (238 respondents) may not be able to reflect the overall perspective of service failure/recovery in mobile commerce. The second limitation is that scenario design is used instead of having respondents experience a service failure in the experiment due to the limited time and resources, which may not reflect the service failure encountered in the real world. The third limitation is that this study has taken three perspectives (distributive, procedural, interactional) of perceived justice, while some previous studies have only considered one, two, or four perspectives of perceived justice.

Some suggestions are provided for future scholars interested in mobile commerce service failure. This study has leveraged the categorisation of previous scholars [34] in the CIT study; thus, service failure is categorised into outcome process, and service recovery is categorised into tangible/psychological. Future scholars can focus on identifying new categories with larger sample sizes. Finally, although this study adopted the common three dimensions of perceived justice (distributive, procedural, interactional), some researchers suggest adding a fourth dimensional view (informational justice [61]) to examine post-recovery satisfaction [37]. For future studies, when perceived justice is considered, instead of following the mainstream three-dimensional view, the four-dimensional view including informational justice should be considered and is worth further investigating.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.L. and C.Y.W.; methodology, C.Y.W.; software, C.Y.W.; validation, Y.K.L., C.Y.W. and Y.T.D.; formal analysis, G.N.T.T. and Y.T.D.; investigation, Y.K.L.; resources, C.Y.W.; data curation, C.Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.W.; writing—review and editing, G.N.T.T.; visualisation, G.N.T.T.; supervision, Y.K.L.; project administration, G.N.T.T.; funding acquisition, Y.T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Scenario of the Experiment

You just moved to a new house, and you planned to host a housewarming party to invite some of your closest friends over in the coming weekend. As you just moved in and needed to buy some tableware, you browsed on a shopping App on your smart phone during lunch break and found some very nice porcelain plates, which you could use as serving plates in the party and for future use. You placed an order through the App immediately as the weekend was just a couple of days away…

- Scenario 1 (High magnitude of failure, tangible recovery)

After 2 days, the goods arrived on time. However, you found out that the quality of the plates were very bad: they were poorly made, and even some of the plates had cracks on it! You found this to be a very severe and unacceptable mistake, so you contacted the in-app customer service right away and described what you had encountered. The customer service staff replied that they were willing to offer a refund or return option for this unsatisfactory product, and on top of that they would like to offer an additional coupon as a compensation for this dis-satisfactory experience. No particular apologies or explanations were given. As the plates you received were not usable and you considered this to be a serious problem for you, you eventually decided to get a refund and bought another set of plates with the coupon given for a discount.

- Scenario 2 (High magnitude of failure, psychological recovery)

After 2 days, the goods arrived on time. However, you found out that the quality of the plates were very bad: they were poorly made, and even some of the plates had cracks on it! You found this to be a very severe and unacceptable mistake, so you contacted the in-app customer service immediately and described what you had encountered. The customer service staff replied within minutes after you sent the message and expressed their sincere apologies on what you had encountered. They explained that they had found out about the quality issue with their supplier just recently and they were already in discussion with the supplier on how to improve the product quality to prevent the same thing from happening again. They only apologized and explained to your complaint, NO tangible compensation, such as additional coupons or refund, were given. As the plates you received were not usable and you considered this to be a serious problem for you, you eventually decided to accept their apologies and explanation, and found another source to buy the plates you needed.

- Scenario 3 (High magnitude of failure, tangible + psychological recovery)

After 2 days, the goods arrived on time. However, you found out that the quality of the plates were very bad: they were poorly made, and even some of the plates had cracks on it! You found this to be a very severe and unacceptable mistake, so you contacted the in-app customer service immediately and described what you had encountered. The customer service staff replied within minutes after you sent the message by saying that they were willing to offer a refund or a return option for this unsatisfactory product. On top of that, they also expressed their sincere apologies on what you had encountered and explained that they had found out about the quality issue with their supplier just recently, and they were already in discussion with the supplier on how to improve the product quality to prevent the same thing from happening again. They would like to offer an additional coupon as a compensation for this dissatisfactory experience. As the plates you received were not usable and you considered this to be a serious problem for you, you eventually decided to accept their apologies and explanation, and chose to get a refund and bought another set of plates with the coupon given for a discount.

- Scenario 4 (Low magnitude of failure, tangible recovery)

After 2 days, the goods arrived on time. You realized that the external packaging was slightly damaged, but the plates were all fine and the quality of the plates were as expected. Even though you had received the goods and the problem of the packaging did not create any damage to the product, you felt the need to advise the seller to avoid any future problems. You contacted the in-app customer service immediately and described what you have encountered. The customer service staff replied that they were willing to offer a refund or a return option for this problem encountered. On top of that, they would also like to offer an additional coupon as a compensation for this dissatisfactory experience. No particular apologies or explanations were given. As slight-damaged packaging was not a serious problem for you, you eventually decided not to replace or to get a refund, but the coupon was still received in your account a few days later.

- Scenario 5 (Low magnitude of failure, psychological recovery)

After 2 days, the goods arrived on time. You realized that the external packaging was slightly damaged, but the plates were all fine and the quality of the plates were as expected. Even though you had received the goods and the problem of the packaging did not create any damage to the product, you felt the need to advise the seller to avoid any future problems. You contacted the in-app customer service immediately and described what you had encountered. The customer service staff replied within minutes after you sent the message and showed their sincere apologies about what you had encountered. They also explained that the damage was caused during to the shipment and they would further contact the freight company to look into this issue. No additional coupons or compensations were given. As slight-damaged packaging was not a serious problem for you, you eventually decided to accept their apology and explanation.

- Scenario 6 (Low magnitude of failure, tangible + psychological recovery)

After 2 days, the goods arrived on time. You realized that the external packaging was slightly damaged, but the plates were all fine and the quality of the plates were as expected. Even though you had received the goods and the problem of the packaging did not create any damage to the product, you felt the need to advise the seller to avoid any future problems. You contacted the in-app customer service immediately and described what you had encountered. The customer service staff replied within minutes after you sent the message and expressed their sincere apologies about what you had encountered. They also explained that the damage was caused during the shipment and they would further contact the freight company to look into this issue. The customer service also offered a refund or a return option for this unsatisfactory product, and on top of that they would like to offer an additional coupon as a compensation for this dissatisfactory experience. As slight-damaged packaging was not a serious problem for you, you eventually decided to accept their apology and explanation and not to replace or to get a refund, but the coupon was still received in your account a few days later.

Appendix B. Questionnaire

Table A1.

The research items.

Table A1.

The research items.

| Distributive Justice | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Procedural Justice | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Interactional Justice | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Post-recovery satisfaction | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

References

- Chong, A.Y.L. Understanding mobile commerce continuance intentions: An empirical analysis of Chinese consumers. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 53, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.; Han, K.; Animesh, A.; Hwang, M. From online to mobile: Linking consumers’ online purchase behaviors with mobile commerce adoption. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Jeju Island, Korea, 18–22 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Agrebi, S.; Jallais, J. Explain the intention to use smartphones for mobile shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.Y.; Chu, J.; Wu, J. Mobile advertising: An empirical study of temporal and spatial differences in search behavior and advertising response. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 30, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Trivedi, M. Mobile shopping through applications: Understanding application possession and mobile purchase. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 39, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxham, J.G. Service recovery influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxham, J.G., III.; Netemeyer, R.G. A longitudinal study of complaining customer evaluations of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.L.; Gan, C.C.; Imrie, B.C.; Mansori, S. Service recovery, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: Evidence from Malaysia’s hotel industry. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2019, 11, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Crisafulli, B. Managing online service recovery: Procedures, justice and customer satisfaction. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 764–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.K.; Wu, W.Y.; Truong, G.N.T.; Binh, P.N.M.; Van Vu, V. A model of destination consumption, attitude, religious involvement, satisfaction, and revisit intention. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 27, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.K.; Bolton, R.N.; Wagner, J. A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Seock, Y.K. Effect of service recovery on customers perceived justice, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth intentions on online shopping websites. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S.; Cho, W. The role of self-service technologies in restoring justice. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.C.; Warden, C.A.; Lee, C.H.; Huang, C.T. Fatal service failures across cultures. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2001, 8, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blodgett, J.G.; Hill, D.J.; Tax, S.S. The effects of distributive, procedural and interactional justice on post complaint behavior. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohary, A.; Hamzelu, B.; Alizadeh, H. Please explain why it happened! How perceived justice and customer involvement affect post co-recovery evaluations: A study of Iranian online shoppers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparoidamis, N.G.; Tran, H.T.T.; Leonidou, C.N. Building customer loyalty in intercultural service encounters: The role of service employees’ cultural intelligence. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Sarkar, J.G.; Sreejesh, S. Managing customers’ undesirable responses towards hospitality service brands during service failure: The moderating role of other customer perception. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, D.; Hyun, S.S. An empirical study of the role of failure severity in service recovery evaluation in the context of the airline industry. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2015, 9, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.R.; Spyrakopoulos, S. Service failures and recovery in retail banking: The customers’ perspective. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2001, 19, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oznur, O.T.; Pinar, B. Pre-recovery emotions and satisfaction: A moderated mediation model of service recovery and reputation in the banking sector. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 388–395. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, R.L., Jr.; Ganesan, S.; Klein, N.M. Service failure and recovery: The impact of relationship factors on customer satisfaction. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.; Pecotich, A.; O’Cass, A. What happens when things go wrong? Retail sales explanations and their effects. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Gursoy, D. The impacts of service failure and recovery efforts on airline customers’ emotions and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1034–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhare, R. A study on customer satisfaction with service recovery procedure in service industry. J. Posit. School. Psychol. 2022, 6, 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, A.; Nguyen, H.; Pham, T. Relationship between service recovery, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: Empirical evidence from e-retailing. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuilken, L.; Robertson, N. The influence of guarantees, active requests to voice and failure severity on customer complaint behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migacz, S.J.; Zou, S.; Petrick, J.F. The “Terminal” effects of service failure on airlines: Examining service recovery with justice theory. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Hung, J.S. The effects of service recovery and relational selling behavior on trust, satisfaction, and loyalty. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 1437–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, S.B.; Prakhya, S.; Sharma, A. Leveraging service recovery strategies to reduce customer churn in an emerging market. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 48, 848–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, G.; Rehman, M.A.; Samad, S.; Rather, R.A. The impact of the magnitude of service failure and complaint handling on satisfaction and brand credibility in the banking industry. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2020, 25, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidow, M. Organisational responses to customer complaints: What works and what doesn’t. J. Serv. Res. 2003, 5, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.F.; Yen, S.T.; Chen, L.H. Online auction service failures in Taiwan: Typologies and recovery strategies. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2011, 10, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Talwar, S.; Islam, N.; Salo, J.; Dhir, A. The effect of the valence of forgiveness to service recovery strategies and service outcomes in food delivery apps. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.C.; Cheng, Y.H.; Chang, C.J.; Yang, S.W. The effect of service failure types and service recovery on customer satisfaction: A mental accounting perspective. Serv. Indus. J. 2012, 32, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, J.W.; Arenson, S.J.; Evans, R.H. An application of equity theory to buyer-seller exchange situations. J. Mark. Res. 1978, 15, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Keena, L.D.; Leone, M.; May, D.; Haynes, S.H. The effects of distributive and procedural justice on job satisfaction and organisational commitment of correctional staff. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 57, 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Norizan, N.S.; Arham, A.F.; Norizan, M.N. The influence of perceived organisational justice on customer’s trust: An overview of public higher educational students. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Fims, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Vveinhardt, J.; Warraich, U.A.; Hasan, S.S.U.; Baloch, A. Customer satisfaction & loyalty and organisational complaint handling: Economic aspects of business operation of airline industry. Eng. Econ. 2020, 31, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y.F.; Wu, C.M. Satisfaction and post-purchase intentions with service recovery of online shopping websites: Perspectives on perceived justice and emotions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Kaul, D.; Sanyal, P. What drives customers towards mobile shopping? An integrative technology continuance theory perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 34, 922–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbrich, K.; Gäthke, J.; Grégoire, Y. How a firm’s best versus normal customers react to compensation after a service failure. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4331–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, A.K.; Schaefers, T.; Walsh, G.; Beatty, S.E. The effect of compensation size on recovery satisfaction after group service failures: The role of group versus individual service recovery. J. Serv. Res. 2019, 22, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Nergiz, A.; Yesiltas, M.; Gunay, T. Human resource management practices and service provider commitment of green hotel service providers: Mediating role of resilience and work engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Lai, M.K.; Hsu, C.H. Recovery of online service: Perceived justice and transaction frequency. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Zhou, Y.; Hussain, K.; Nair, P.K.; Ragavan, N.A. Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty? A study of international students in Malaysian public universities. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2016, 24, 70–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, I.M.; Gaur, S.S. Consequences of consumers’ emotional responses to government’s green initiatives: Insights from a scenario-based experimental study. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 30, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.C.; Lii, Y.S. Handling online service recovery: Effects of perceived justice on online games. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, B.; Singh, J. Service failures in e-retailing: Examining the effects of response time, compensation, and service criticality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.C.; Ho, C.W.; Lii, Y.S. Is corporate reputation a double-edged sword? Relative effects of perceived justice in airline service recovery. Int. J. Eco. Bus. Res. 2015, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C.; Svingstedt, A. Mobile shopping and the practice of shopping: A study of how young adults use smartphones to shop. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.R.; Tek, N.T.; Anwar, A.; Lapa, L.; Venkatesh, V. Perceived values and motivations influencing m-commerce use: A nine-country comparative study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Radzi, S.M. Understanding tourist mobile hotel booking behaviour: Incorporating perceived enjoyment and perceived price value in the modified Technology Acceptance Model. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 17, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, N.T.; Deng, H.; Tay, R. Critical determinants for mobile commerce adoption in Vietnamese small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 456–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlakis, M.; Papagiannidis, S.; Li, F. Retail spatial evolution: Paving the way from traditional to metaverse retailing. Electron. Commer. Res. 2009, 9, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphaeli, O.; Goldstein, A.; Fink, L. Analysing online consumer behavior in mobile and PC devices: A novel web usage mining approach. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2017, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, J.H.; Wünderlich, N.V.; Wangenheim, F. Technology mediation in service delivery: A new typology and an agenda for managers and academics. Technovation 2012, 32, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.E.; Lee, Y.H.; Hsu, J.W. Does service recovery really work? the multilevel effects of online service recovery based on brand perception. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the dimensionality of organisational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).