Abstract

The concept of inclusion has moved beyond being a social construct and has received widespread attention from organisational scholars and practitioners due to its varied effects on employee behaviours and sustainable organisational outcomes. This study tests the impact of inclusive leadership on the withdrawal behaviours of employees. Perceived insider status is used as a mediator and distributive justice as a moderator. This study has collected data from nurses, physicians, and paramedics of selected tertiary hospitals in Pakistan. A convenience sampling technique was used to collect data. A total of 264 responses were analysed using the PLS-SEM approach. Results found that inclusive leadership was positively related to perceived insider status and negatively related to employee withdrawal. Perceived insider status mediated the link. The impact of inclusive leadership on perceived insider status was stronger when distributive justice was high. This study offers multiple theoretical and practical implications, as it uses justice theory as a mechanism to explain boundary conditions around the effects of inclusive leadership on employee perceptions of being insiders, managing employee withdrawals, and improving sustainability in employee relations.

1. Introduction

The modern business world emphasizes inclusion as a key organisational characteristic that is important for gaining a sustainable competitive advantage. Initially, inclusion was perceived as an approach to managing diversity in organisations by offering equal and just opportunities to distinct segments of society, including women, minorities, the disabled, and people of colour [1]. Apart from demographic diversity, researchers now focus on inclusion-based employees’ attitudinal, behavioural, and needs-based diversity [2]. Inclusion is defined as the extent to which employees perceive that they are valued members of the workgroup and experience the treatment that satisfies their needs for belongingness and uniqueness [2]. This conceptualisation of inclusion by Shore et al. proposes that inclusion must consider individuals’ two important needs, i.e., need for belongingness (the need to establish and improve sustainability in interpersonal relationships) and uniqueness (the need to maintain a distinct perception of self). In other words, it is to firstly acknowledge the fact that employees display some uniqueness in terms of their needs, feelings, and self-concept, and, secondly, they also need to display their uniqueness in an organisation such that their voice is being heard.

When applying such inclusive strategies, managers enable employees to embrace diversity and make employees feel that they are insiders in the workplace [3]. In such a situation, employees may offer their full potential in various challenges to foster a conducive environment in organisations [3]. Such an environment, supported by inclusive leaders, will help employees shape their perception of inclusion and willingness to remain in the organisation and engage in citizenship behaviours [4]. Past research has found positive impacts of inclusive leadership on a variety of outcomes. For example, a meta-analytic study of 184 studies has found a positive impact of inclusive leadership on employee discretionary behaviours, such as innovative work behaviour, voice behaviour, and task performance. The study also found that psychological safety, identification with the leaders, and quality of leader-member exchange are important mediators in these links [5]. Research suggests that inclusive leadership can enhance involvement in creative work [6]. Although enough empirical evidence is present regarding the importance of inclusive leadership for organizationally relevant variables, research on inclusive leadership is still in its infancy, and the most fundamental questions remain unexplored [2].

For example, a study presented a theoretical model after a thorough review of the literature based on social identity theory [7]. They proposed that inclusive leaders facilitate belongingness (sharing decision-making, supporting individuals as group members, and maintaining equity and justice), value uniqueness (encouraging diverse contributions and supporting contributions), and can develop followers’ perception of being insiders (inclusion), which will, in turn, reduce their turnover intention. This study thus extends its proposition by providing empirical evidence for this theoretical model.

Inclusive leaders are organisational leaders who embrace inclusion and belongingness and can garner employee support, gain loyalty, and increase employee satisfaction and happiness [8]. Research suggests that inclusive leaders are those who treat individuals and groups transparently and fairly. They base their perceptions solely on distinct qualities individuals possess rather than considering stereotypes as the basis for their attitude. Secondly, inclusive leaders value, regard, and accept the uniqueness of each individual. Thirdly, inclusive leaders consider individuals’ uniqueness as a resource for teams and organizations by integrating diverse points to improve the quality of decision-making. Thus, by engaging in such behaviours, inclusive leaders create an environment of inclusion and belongingness. Fourthly, inclusive leaders ensure justice and equity [9,10].

It is also believed that inclusive leadership as a philosophical approach is more humanistic than other leadership styles, as it is a person-centred approach, in contrast to organisation-centred approaches [11]. Inclusive leadership is relationship-oriented, focuses on affective behaviours, and is grounded in principles of social justice [8]. Inclusive leadership is relationship-oriented, focuses on affective behaviours, and is grounded in principles of social justice [8]. More specifically, inclusive leaders focus more on nurturing, collaboration, and building reciprocal relationships, as opposed to conventional hierarchical relationships that focus on mere compliance and submission [8]. Inclusive leaders fulfil employee needs of belongingness and value for uniqueness in order to foster a sense of both inclusion and being insiders. This sense of belonging, achieved through inclusive practices, is fluid and mutable, which changes with time, especially when there are multiple stereotypes and insecurities already available against marginalized communities and personalities [12]. Therefore, establishing sustainable employee relationships is a key challenge today’s leaders face in corporations and other organizations [13].

A study reviewed the literature on inclusive leadership to provide conceptual clarification and the nomological net of inclusive leadership [14]. Their review proposed that inclusive leadership satisfies employees’ needs for uniqueness and belongingness and, thus, creates an “employee feeling of being home” (p. 1). By providing equitable access to employees, inclusive leaders enable them to feel that they are an insider in their organisation.

They also suggested numerous avenues for future research. For example, they noted that Western cultures dominate research on inclusive leadership. Very little research has been conducted on Eastern cultures [14]. Although Eastern cultures regard hierarchy more than Western cultures, employees in these cultures are less likely to argue with their leaders; therefore, how inclusive leadership impacts attitudes and behaviours in Eastern cultures is an important topic of future research. This review also noted that research had ignored the perceived insider status construct, which offers greater contributions concerning inclusive leadership and employee outcomes. Insider status is an immediate outcome of leader behaviour, which eventually impacts employee behaviours in the workplace [15].

A recent study that employed the Delphi method and interviewed panels of experts found that certain variables related to employees are also important for improving corporate sustainability. Variables such as employee relations, a feeling of connectedness, fairness in wages and other resources, the provision of equal opportunities, equitable working hours, and free association are elated in corporate sustainability [16]. This study thus provides empirical evidence of such leadership behaviours that promote connectedness and belongingness, which in connection to institutionalized justice, will improve sustainability in employee relationships by enhancing feelings of being insiders and being connected [17,18].

Therefore, the major objective of this research is to test the impact of inclusive leadership on employee insider status and employee withdrawal behaviour, the two major forms of maintaining sustainable relationships among leaders and employees. Moreover, employee perception of distributive justice is modelled as a moderator between inclusive leadership and insider status.

2. Model and Hypotheses

2.1. Inclusive Leadership and Perceived Insider Status

The notion of inclusive leadership reflects leader behaviour that regards employee voice in managerial decision-making [10]. In the field of management, the concept of inclusion was first introduced by [19], such that the “words and deeds by a leader or leaders that indicate an invitation and appreciation for others’ contributions” are considered. Inclusive leadership creates a situation in which both employees and leaders are in a win-win position as the views and expressions of employees are taken into consideration by leaders [20].

Inclusive leaders are considered highly valuable leaders who embrace their employees at all levels and provide greater support; thus, they create an inclusive organisational climate [21]. Inclusive leadership contains three major foci: (1) leaders display a greater level of tolerance toward employees’ views, embrace employee errors rationally, and provide greater support and guidance to employees. (2) Leaders invest their time and resources in the training of the employees, celebrating their achievements and avoiding negative dispositions, such as jealousy and cynicism towards employees [22]. Inclusive leaders treat employees transparently and fairly, display a positive attitude towards employees, and have an equal share in organisational benefits.

Inclusive leadership may share some conceptual similarities with other leadership styles, such as empowering leadership or ethical forms of leadership. However, it also holds a unique nature in employee inclusiveness, uniqueness, belongingness, and acceptance [7]. Inclusive leadership does not focus on employee transformation to new behaviours; rather, it focuses on leader behaviour that creates space for employees’ voices, views, and abilities [20]. Inclusive leadership emphasizes paying attention to employees’ need to be part of a group. Inclusive leadership makes leaders accessible to employees. Despite the minimal overlap between inclusive leadership and other leadership styles, it is noted that inclusive leadership has certain unique tenets untapped by other leadership styles [7]. More specifically, inclusive leadership’s role in creating employee feelings of inclusion, and being part of a core group with the leader, are important. Research in these dimensions is still in its infancy; however, available evidence suggests that inclusive leadership is related positively to perceived organisational support, which further fosters employee innovative behaviours [23].

Research suggests that inclusive leaders provide support and assistance to their employees instead of giving orders and controlling their behaviours through punitive measures. Inclusive leaders offer their employees the requisite resources, autonomy, and freedom to perform their tasks [6,20]. In this way, inclusive leaders can develop positive attitudes in team members.

At the same time, there exists a kind of relational leadership. A key characteristic of inclusive leaders is their openness. By being open to varying ideas and views, they can invite and embrace people with differing viewpoints. They can create an environment where no one can feel excluded [6,20]. They can also offer strong emotional and socio-economic support to their employees. By doing so, they can send a strong message across organisations that leaders are open enough to accept different and alternate ideas and voices [20,24].

Inclusive leadership also sends a message that employees’ unique contributions are recognised and welcomed [21]. This leadership style also reflects leaders’ willingness to provide support, whether tangible or intangible, to employees in their time of need [23]. Moreover, inclusive leadership also engages employees in decision-making.

Despite the importance of inclusive leadership in leadership research and its impact on employee involvement and inclusion, the empirical relationship between inclusive leadership and perceived insider status remains untapped.

A study from Pakistan found that inclusive leadership positively develops employee trust in leadership and leader integrity, fostering employee citizenship behaviours [4]. They further argue, using causal attribution theory, that inclusive leaders, by their openness and inclusion, can change employee attributions, which can further impact their attitudes and behaviours.

Inclusive leaders also encourage employees to share their teams’ voices and present new and innovative ideas that challenge the status quo [24]. Inclusive leadership also increases employees’ perceptions of organisational support, thus resulting in positive organisational behaviours [23].

Perceived insider status is the employee’s perception of being included in organizational workings [25]. Perceived insider status is an employee’s feeling about the space they have occupied in workgroups and teams. It is also thinking about how they are being valued in the organizations [26]. With regard to belongingness, employees’ perceptions are divided into two groups: the inner group and the outer group. Employees who are high on perceived insider status will associate themselves with the inner group and show greater dedication and commitment to their organization [27].

Sustainability in employee–organisation relationships receives enormous focus from academics and practitioners [28]. Employees’ attitudes and behaviours towards organizations are determined by the way they think they are being treated in their organizations. Stamper and Masterson (2002) operationalised the perceived insider status that represents the employee–organisation relationships, which is defined as the “extent to which an employee of an organisation perceived him–herself as an insider to a specific organisation” [25]. Feelings of perceived inside status enable employees to think of having both a “personal space” and a sense of belonging in the organisation [26].

Insider status suggests reciprocity of employee behaviours beyond traditional transactional exchanges. Sustainability in employees’ relationships, mutual trust, respect, regard for each other, formal authority, and support from leadership are key factors that garner employee behaviours favouring organisations [29].

Research indicates that employees who feel they are provided ample support for any domain-relevant skills, and feel that they enjoy insider status in the organisation, engage in positive behaviours [27,28,29]. Perceived inside status positively relates to organisational citizenship behaviour and mediates the impact of perceived organisational support and organizational citizenship behaviour and deviant behaviour [25]. Perceived organisational membership [25] covers three dimensions, including belonging, mastering, and need fulfilment. Belonging dimensions include three constructs that refer to the relatedness of employees within the organisation: perceived personal space and recognition of insider status (perceived insider status), the feeling of possessiveness (psychological ownership), and self-definition with the work group (organisational identification). A study tested the belonging section of the POM model to determine its discriminant validity and its impact on important organisational outcomes, such as job satisfaction and turnover intention [30]. The results of a multiple regression analysis of a sample of 347 workers indicate that the amount of variance explained by perceived insider status in job satisfaction and turnover intention was greater than the other two predictors of the model, such as psychological ownership and organisational identification. Authors suggest that perceived insider status has received few empirical studies that warrant the need to establish its construct validity and nomological net [30].

Perceived insider status refers to the sense of belonging in the organisation, which is developed through one’s mutual and sustainable relationships with relevant others in the organisation [31]. Research on antecedents to perceived insider status reveals that perceived organisational support positively relates to insider status. A study of 271 supervisor-subordinate dyads in China found that perceived insider status mediated the positive impact of delegation on innovative behaviour [32].

As perceived insider status is regarded as the individual perception of being an ‘insider’ in organisational processes, research has identified constructs similar to perceived insider status, such as ‘inclusion’ (the degree to which an employee feels that they are a part of critical organisational processes) and “access to information, connectedness to co-workers and ability to participate in and influence the decision-making processes” [33]. The theory of perceived insider status suggests that organisational procedures and the leader–follower relationship, based on transparency and fairness, will greatly enhance ‘insider’ perception among employees and improve sustainability in employee relations [25,34]. Research on the theory of authentic leadership suggests that authentic leaders who display genuine and transparent behaviours in organisations include followers in decision-making by offering their suggestions, inviting their feedback, and allowing them to speak their minds [35].

Earlier research on insider status reported a positive impact of organisational level factors, such as perceived organisational support [25,32]. In a study of 210 employees in Canada, authors found that an organisational climate characterised by justice and fairness is positively related to perceived insider status. The study also found the importance of leader–member exchange quality in strengthening the positive impact of pro-diversity practices with perceived insider status [34]. The research also suggests that perceived insider status, coupled with leader–member exchange, enhances the employee feeling of organisation-based self-esteem, thus improving task performance. Within the relational model, which considers ‘social inclusion’ and sustainable interpersonal relationships as basic human needs, authors suggest that perceived insider status may send an important clue of inclusion among employees, which will foster their task performance and may decrease withdrawal behaviours [34].

Globally, making an inclusive environment in organisations is considered obligatory partly because of its impact on performance and partly due to the legal obligations of maintaining justice and ending discrimination. A study on diversity management used a large survey sample of US employees. It tested the role of diversity policies and inclusive leadership on work group effectiveness and their differential effects on people of colour and whites. The study found that inclusive leadership practices were more effective for people of colour than whites and were more effective than simply the diversity policy [1]. This study implies that making the policies is not sufficient; how managerial practices embrace diversity and promote inclusion is important for work group effectiveness and harmony [36]. Inclusive leadership removes barriers that prevent employees from participating in organisational activities and helps them maintain membership in the organisations [24,37]. Although specific studies testing the relationship between inclusive leadership and insider status are scarce, empirical studies have found a positive impact of inclusive leadership on psychological safety and psychological empowerment [38]. This study posits that:

Hypothesis 1.

Inclusive leadership is positively and significantly related to perceived insider status.

A stronger sense of perceived insider status is rooted in employee sense-making of being important to the organisation. On the one hand, this sense fulfils the employee’s need for inclusion, agency, and control. On the other hand, it increases the employee’s sense of being a responsible citizen [25]. Such a sense of responsibility and citizenship will likely be positively related to organisational attitudes, such as job satisfaction [32], affective commitment [31], intention to stay [39], and organizationally supportive behaviours such as task performance and innovative behaviours [32].

The organisational inducement model suggests that employee contributions depend upon the inducements provided by employers [40]. These inducements, in the shape of organisational support, a delegation of authority, time demands, or inclusive leadership, will motivate employee contributions in the same direction and persistence wherein inducements are perceived to be useful and significant. Perceived organisational support, and participative decision-making as a form of organisational inducement, are significant predictors of insider status and organizational citizenship behaviour [40]. Perceived insider status mediates the relationship between inducements and organizational citizenship behaviour. Employees’ perception of insider status will be a significant facilitator in this link.

When employees speak up their minds in organisations, leaders typically consider them troublemakers and don’t value their unique contributions [41]. Such a situation can result in employee isolation, victimisation, and punishments, resulting in lower levels of employee well-being and higher levels of employee withdrawals [42].

However, inclusive leaders, on the other hand, provide emotional support, openness for dissenting voices, and opportunities for creative ideas by developing an environment of psychological safety and insider status perceptions [43]. This way, they are able to reduce employee withdrawals. Thus, this study infers that:

Hypothesis 2.

Perceived insider status will be negatively related to employee withdrawal behaviour.

Hypothesis 3.

Perceived insider status will mediate the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee withdrawal behaviour.

2.2. Inclusive Leadership and Procedural Justice

Transparency and justice are highly regarded values in social and organisational lives [44]. Fairness in organisations, termed organisational justice, consists of three foci, i.e., procedural justice, interactional justice, and distributive justice. Procedural justice refers to employees’ perceptions about procedures and policies prevailing in organisations [45,46]. The literature supports the notion that procedural justice in organisations ignites employee cooperative behaviours and increases task performance [47]. Although procedural justice is about how work is regulated in organisations, distributive justice is related to fairness in work outcomes received by workers [48].

However, interactional justice relates to fairness in interpersonal communication and information sharing [48]. Procedural justice, compared to its two other related dimensions, such as distributive justice and interactional justice, is more strongly related to organisational outcomes, such as organisational citizenship behaviour and organisational commitment [49,50].

Distributive justice is strongly related to pay and other organisational outcomes, whereas interactional justice is related to the relationship between employees and supervisors [25]. Our study has focused on procedural justice because it is not only strongly related to organisational outcomes, but it is a more institutionalised form of justice in the leadership literature [49,50,51]. It may strengthen and improve sustainability in employee relations. A recent study has found that employment relationships based on mutual investments can improve organizational sustainability [18].

A study collected data from IT professionals from Turkey and found a positive impact of inclusive leadership on work engagement [44]. They also found an important role for procedural justice between inclusive leadership and work engagement. They also suggested checking other justice perceptions, such as distributive justice and interactional justice in relation to inclusive leadership, to see their synergetic effects on employees’ perceptions and behaviours. Procedural justice is strongly linked with the concept of fairness in managerial decision-making, and it further fosters positive behaviours in the employees in the employees [52]. Research has outlined the role of justice perceptions in a link between leadership styles and positive organisational behaviours, such as creative behaviours [53], satisfaction with the job, intrinsic motivation satisfaction with the job [52], intrinsic motivation, and commitment to the organisation [52,54].

Research in ethical forms of leadership has also considered justice perception as an important aspect and has also considered justice perception an important boundary condition for leadership effectiveness and commitment to the organisation [52]. Research in ethical forms of leadership has also considered justice perception as an important aspect of the same, and it has also considered justice perception as an important boundary condition for leadership effectiveness [55]. Therefore, the absence of procedural justice and fairness can lead to undesired and unethical behaviours, such as counterproductive work behaviour, revenge, retaliation, and emotional exhaustion [45,51].

The literature also suggests that higher levels of procedural justice signal two feelings in the group members: that they feel that they are being valued by the leaders in the organisations, and that being a member of the group is a matter of pride and self-identity for them [45]. To put it differently, when individuals receive fair and transparent treatment, they feel themselves as part of the inner group and will be willing to accept and embrace leadership decisions and their outcomes, comply with procedural rules and laws, and maintain their memberships in the group and organisations [45].

Research suggests that procedural justice offers employees an opportunity to participate in decision-making, thus achieving importance in leader-employee relations [45]. Procedural justice also allows employees to share their voices in organisations and, thus, to receive support from supervisors and organisations [50]. Procedural justice is rooted in leader behaviour characterised by equity in leader-follower relationships, allowing employees to impact organisational outcomes [56].

Hypothesis 4.

Distributive justice will moderate the relationship between inclusive leadership and insider status. The impact of IL on insider status will be higher when DJ is higher than lower.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedures

This study was conducted in public sector hospitals in Pakistan. Data were collected from physicians, nurses, and para-medical staff. The health sector in Pakistan had been a major focus recently due to the COVID-19 outbreak. This sector experiences significant changes, such as a great inflow of funds, new recruitments, deaths of healthcare workers due to COVID-19, heightened focus from media, etc. [57]. Therefore, this study focused on the health sector to test the effects of inclusive leadership on withdrawal behaviour. Leadership studies in the Pakistani health sector are already scarce [58]. Respondents were contacted through institutional heads after getting approval.

3.2. Measures

To measure inclusive leadership a 9-item scale was used [6]. This model contains three dimensions: accessibility, openness, and availability. Sample items include: “The manager is open to hearing new ideas”, “The manager encourages me to consult them on emerging issues”, and “The manager is ready to listen to my requests” for openness, accessibility, and availability, respectively.

Employee withdrawal behaviour was measured using a 4-item scale [59]. A sample item includes “I sometimes consider taking on another job”.

Distributive justice was measured using the 5-item scale developed by [60]. A sample item includes “Do those outcomes reflect the effort you have put into your work?”. Participants were asked to refer to the outcomes they receive from the leaders in terms of pay, evaluations, assignments, promotions, and other rewards.

A scale developed by [25] was used to measure insider status. A sample item includes “I feel I am an insider/outsider in my work organization”.

The responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 refers to “strongly disagree” and 5 refers to “strongly agree”.

3.3. Participant Profiles

The population of this study was composed of doctors, nurses, and para-medical staff working in eight tertiary care hospitals in the twin cities of Pakistan, i.e., Islamabad and Rawalpindi. Due to different challenges in the recruitment of participants in this study, a convenience sampling technique was applied to collect data. Similar studies from Pakistani healthcare participants, conducted by researchers who do not belong to the healthcare sector, have also used the convenience sampling technique, e.g., [58]. Apart from a variety of skills, these three groups have an important role in the organizational culture of hospitals. They become united on common issues with hospital leadership and also reflect an ideal diversity.

The G*Power software was used to determine the suitable size of the sample. Based on the view of the parameters of the model, the software results suggest that the minimum sample size should be 109 respondents to obtain statistical power [61].

A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed. Out of these, 270 were returned. Six questionnaires were discarded because of incomplete information. A total of 264 questionnaires are useable, thus constituting an 88% response rate. Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the sample. There was 44 percent of females, and 42 percent of nurses participated in the study.

Table 1.

Participants details.

3.4. Model Estimation

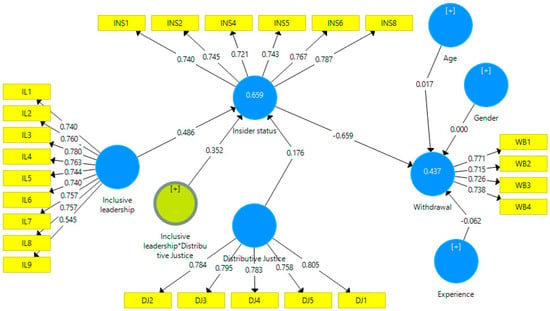

This study used partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) to test the hypotheses of this study, following the guidelines of Hair et al. [62]. The PLS-SEM technique is popularly used in the causal-predictive model to explain and predict the models [63]. A popular two-step approach has been used to analyse and interpret the data, as recommended by Hair, Hult, Ringle, and Sarstedt [62,64]. In the first step, the measurement model is estimated and, in the second step, the structural model is tested. For a better measurement model, the accepted value of factor loadings is 0.708 with a t-statistic of ±1.96. Values of 5% of the confidence interval should not contain zero [65,66]. The value of factor loading, up to 0.50, is also adequate in some cases [62]. The results of the measurement model are displayed in Table 2 and Table 3. Figure 1 also shows the values of various estimates.

Table 2.

Reliability and Validity.

Table 3.

HTMMT Approach.

Figure 1.

Measurement model.

4. Empirical Analysis

Construct reliability and validity are estimated in measurement model analysis, as this study has used reflective constructs represented by indicators. Therefore, to know the contribution of each indicator to its focal construct, criteria of factor loadings are applied [62,67]. The value of factor loading surpassing 0.708 will indicate sufficient indicator reliability; however, in some cases, values above 0.050 should be retained [65,66]. Table 1 presents Smart PLS output for the values of outer loadings. All outer loadings fulfil the requisite criteria, except for two items in insider status that were deleted due to factor loadings of less than 0.50. This indicates an overall better indicator reliability of the constructs of the model. The second approach to knowing construct reliability is the estimate of Cronbach’s Alpha or composite reliability [68,69]. Composite reliability (CR) is used to check whether all indicators represent the same focal construct [70]. The acceptable value for both estimates is that the value should be above 0.50. Again, values of Cronbach Alpha and CR are greater than 0.50, thus indicating better reliability.

Average variance extracted (AVE) criteria are applied to test convergent validity. Convergent validity checks whether all items of a particular construct converge on the same construct and share at least fifty percent variance [71]. AVE values greater than 0.50 are reflective of convergent validity. Again, Table 1 indicates that values of AVE are greater than 0.50. Therefore, the convergent validity is also confirmed.

The measurement model also includes the estimation of discriminant validity. Discriminant validity estimates whether differently conceptualised constructs are actually and empirically different and do not overlap [62,71]. Table 2 presents the results of the Heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, popularly called the HTMT approach. All the values of HTMT are less than 0.90, thus indicating discriminant validity [62,71,72].

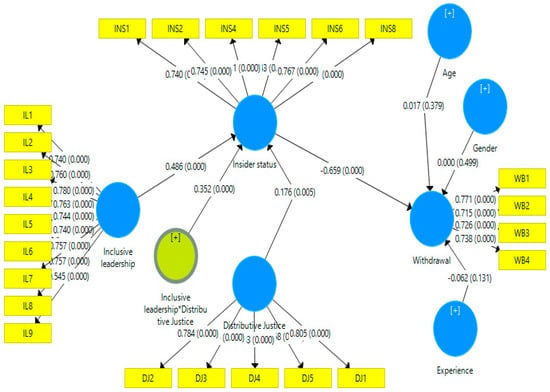

The second step after the measurement model is testing the structural model. This study followed a five-step approach to estimate the structural model [62]. Results of the structural model are displayed in Table 4 and Figure 2. The first step includes examining multicollinearity issues among exogenous variables in the framework. The results in Table 4 indicate no multicollinearity issue in the model, as all VIF values are less than 3.3 [73].

Table 4.

Hypotheses testing results.

Figure 2.

Structural model.

In the second step, values of beta coefficients are obtained through PLS-SEM using the bootstrapping method with 5000 resampling. We have used age, gender, and experience as control variables in the model. The impact of all these variables is insignificant, thus showing no difference among groups based on age, gender, and experience regarding inclusive leadership perceptions and its impact on other variables in the model. Table 4 indicates that beta values for all hypotheses are in the stated direction and are significant. Thus, all hypotheses are accepted. For example, the first hypothesis is concerned with the positive relationship between inclusive leadership and insider status. The results suggest that the beta coefficients are β = 0.486, t = 7.094 (>1.96), and p < 0.05. It indicated that inclusive leadership has a positive and significant impact on insider status.

The second hypothesis was concerned with a negative and significant impact of perceived inside status on withdrawal behaviour, which was also supported (β = −0.659; t = 21.272; p < 0.05). The third hypothesis proposed mediation of insider status between inclusive leadership and withdrawal behaviour. Results of specific indirect effect found support for this hypothesis (β = −0.320; t = 6.405; p < 0.05).

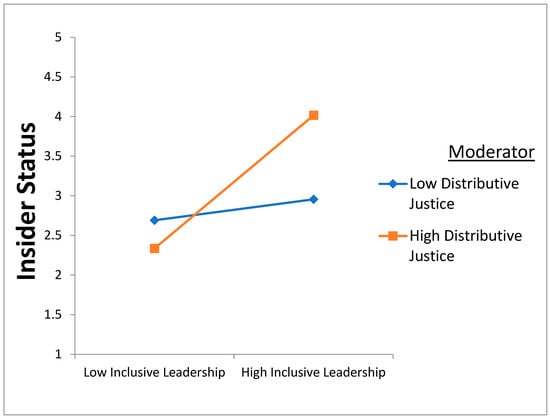

The fourth hypothesis was concerned with moderating the role of distributive justice. It was hypothesized that the impact of inclusive leadership on insider status would be stronger when distributive justice is high rather than low. An interaction term between inclusive leadership and distributive justice was created to test this hypothesis, which was regressed on insider status. Results of this interaction term (moderating effect) are significant (β = 0.352; t = 8.178; p < 0.05). Additionally, a moderation graph was also developed to see the moderating effect. Figure 3 indicates the conditional effect of distributive justice, such that the impact of inclusive leadership on insider status is strong when distributive justice is also high.

Figure 3.

Moderation of withdrawal.

The graph in Figure 3 represents the synergistic effect where higher levels of distributive justice enhance the effect of inclusive leadership on insider status or, in other words, when there is a change in the level of distributive justice it enhances the bivariate relationship between inclusive leadership and insider status [74]. The graph specifies that the lines are not parallel, demonstrating that the interaction effect is supported. The high distributive justice is relatively steeper and increased marginally as inclusive leadership changes from low to high. Thus, the relationship between inclusive leadership and insider status becomes stronger with high levels of distributive justice. But, for low levels of distributive justice, the slope is less steep: it progresses towards flatness, indicating a weaker relationship between inclusive leadership and insider status when the justice is low.

After checking path results for hypothesized relationships, f2 values are estimated to see each path’s relative strength and relevance [62]. Table 4 indicates that inclusive leadership has a large effect size with insider status (f2 = 0.270). The effect size of insider status with withdrawal is large (f2 = 0.768). Values of R square are also calculated to see how much exogenous variables of the model explain variance in endogenous variables of the model. Results indicated that model predictors explain 66% and 43% variance in insider status and withdrawal behaviour, respectively [75].

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

This study tests the impact of inclusive leadership on insider status and employee withdrawal behaviour and checks insider status as a mediator between inclusive leadership and withdrawal. At the same time, distributive justice moderated the link between inclusive leadership and withdrawal. To do so, we collected data from employees in health sector organisations and obtained the results of partial least square structural equation modelling through Smart PLS to confirm that all the hypotheses being studied in our paper hold.

The first hypothesis studied in our paper was about the impact of inclusive leadership on perceived insider status. Results found support for this hypothesis. These results are consistent with the theory of organizational justice, such that when leaders engage in behaviours that ensure interpersonal transparency and value their employees and their input in decision-making, it signals employees to feel included and regarded in their organisations. The concept of perceived insider status includes employees’ needs for belongingness, relatedness, feeling of possessiveness, mastery, and need fulfilment [26]. Inclusive leaders, through their non-discriminant behaviours, fulfil employee expectations for justice [76]. Theoretically, inclusive leadership behaviours will enhance employees’ perceived insider status. This study offers empirical evidence for this theoretical proposition. Overall, empirical studies on the nomological net of insider status are scarce; this study, thus, offers an important contribution towards sustainable employee relations [30].

The second hypothesis studied in our paper was about the impact of insider status on employee withdrawal behaviour. Research has acknowledged the role of perceived insider status in employee retention [29]. Research has also found a negative link between perceived insider status and negative gossip about organizations and a form of withdrawal behaviour [56]. Yet, a very recent study from China also found a negative association between perceived insider status and employee withdrawal [77].

The research on inclusion also supports the notion that, when employees feel that they are an insider and that they are part of a core group with a leader, they are likely to develop a sense of being a responsible person and will maintain citizenship behaviours, and thus, are likely to remain in the organisation [43]. Such an environment of trusting relationships between leaders and employees discourages employee withdrawal behaviour and enhances sustainability in employee relationships [17].

The third hypothesis studied in our paper was about the mediation of perceived insider status between inclusive leadership and employee withdrawal behaviour. The results obtained in our paper also supported this hypothesis. Our finding is in line with the evidence suggesting that insider status is an important mediating mechanism, linking different HR-related practices, leadership styles, and other predictors with employee attitudes and behaviours [40,78]. Reviewing the literature on voice and its effects on various levels in organizations, Bashshur and Oc [79] contended that individuals’ voices, if heard and acknowledged, will result in positive outcomes such as OCB and other relevant variables. However, once their voice is not heard, people will engage in withdrawal behaviours, including absenteeism, tardiness, lack of commitment, and intention to quit the organization. To work in this direction, this study thus provided a framework suggesting that inclusive leadership, which is a voice-acknowledging leadership style, will enhance the employee feeling of insider status; in other words, the employees working with inclusive leaders will consider that they are being heard. Such feelings will negatively impact withdrawal behaviours.

The fourth hypothesis studied in our paper was about moderating the role of distributive justice between inclusive leadership and insider status. The results and moderation graph obtained in our paper supported this hypothesis as well. Justice perceptions offer important boundary conditions for nurturing positive behaviours among employees [51,80,81], and the organisational justice model offers greater insight into how employees develop insider status [25]. In addition, research has outlined the relationship between inclusive leadership justice perceptions. For example, Cenkci, Bircan, and Zimmerman [44] found positive mediation of procedural justice between inclusive leadership and work engagement. However, they also proposed that distributive justice can function as an important boundary condition for the effects of inclusive leadership on employee behaviours. To work in this direction, this study has thus answered the calls of research and filled this gap to know that mere interaction and formal procedures are not necessary. Equitable distribution of resources, powers, and autonomy among employees are keys to positive employee behaviours.

This study, therefore, argues that inclusive leadership will be strongly related to employee insider status when distributive justice is high. Inclusive leaders also offer some sort of justice in the organisations by treating employees fairly and providing equal opportunities to employees. However, in contrast to interactional and procedural justice, distributive justice may affect employees’ feeling of being valued by leaders. Therefore, distributive justice, in conjunction with inclusive leadership, will affect employees’ feelings of perceived insider status.

A study used organisational membership theory to know how HR practices, focusing on belongingness, need fulfilment, and mattering, are related to older workers’ intention to stay [39]. The study found that when older workers experienced HR practices tailored to providing needs satisfaction, belonging, and mattering, they perceived higher levels of insider status, which developed their intention to stay. The study also used interactional and procedural justice to mediate HR practices and insider status.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

Results are in line with the justice theory, which posits that employees have greater regard for fairness and transparency in leader behaviour that increases their perception of being valued in organizations [82]. Leadership behaviours that support fairness and transparency in the distribution of resources in the organizations will result in employees’ perception of feeling at home. Such a conducive environment will increase employee retention and engagement and discourage withdrawals [3]. It will also improve sustainability in employee relationships with their leaders. Such sustainability is important for overall organizational sustainability [18]. This study also contributes to country or culture-specific studies. Pakistan is a collectivist society where group orientation and cooperation are highly valued [83]. People in Pakistan have a strong desire for belongingness, social inclusion, and ‘collective will’ [84]. Therefore, our study contributes to the understanding that leadership styles and practices that promote inclusion, justice, and collectivism will result in harmonious group behaviours, foster employee retention, and mitigate withdrawals [37,85].

5.3. Practical Implications

Several studies in the nursing literature focus on leaders’ behaviour that supports retention and decreases withdrawal behaviours. However, the findings of this study suggest that leaders’ behaviours that focus on inclusion and satisfaction of employees’ needs of belongingness and uniqueness will create an environment where they will feel that they are a member of the in-group, and thus experience less withdrawal behaviour.

This study also offers contributions regarding distributive justice perceptions of nurses, such that inclusive leaders who also provide equitable rewards for nurses’ contributions will be more effective than others. The findings of this study are important for nurses, as nurses in the Pakistani environment have fewer decision-making opportunities and other important organisational events, and thus, seldom feel part of an inner group. Therefore, promoting inclusive leadership will have greater effects on nurses’ retention and satisfaction.

5.4. Limitations and Extensions

Despite various strengths, this study also has a few limitations. For example, this study employs a cross-sectional design, which could result in a limited causality relationship. In our sample, data were collected through a convenience sampling technique which may have ignored some important respondents. Therefore, future research should employ a more diverse sample and collect data through probability sampling techniques. This study has tested the role of inclusive leadership and used distributive justice as a moderator. Future research may use interactional and procedural justice as a moderator.

Organisations have become extensively diverse; therefore, healthcare leaders need to develop an inclusive environment characterised by justice and fairness to get a greater potential of employees by developing a match with them. It will make cohesive teams, but it will also help leaders manage employee withdrawals. This study uses the structural equation model to test the impact of inclusive leadership on insider status and employee withdrawal behaviour, checks insider status as a mediator between inclusive leadership and withdrawal, and checks how distributive justice moderated the link between inclusive leadership and withdrawal. Extensions of our paper include applying the approaches used in our paper to analyse issues relating to leadership [86,87,88,89] and employees [90], as well as to analyse other issues such as capital structure [91], the stock market [92,93,94,95,96,97], tax aggressiveness [98], production [99], consumers [100], purchasing intention [101], macroeconomics [102,103,104], energy [105,106], and some issues in sustainability [107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and M.U.; methodology, H.J.S., S.A. and M.U.; software, H.J.S. and S.A.; validation, S.A., M.U. and W.-K.W.; formal analysis, H.J.S., S.A. and M.U.; investigation, S.A., M.U. and W.-K.W.; resources, J.P.O. and W.-K.W.; data curation, H.J.S. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J.S., S.A. and M.U.; writing—review and editing, J.P.O., S.A. and W.-K.W.; visualization, S.A., M.U. and W.-K.W.; supervision, S.A. and W.-K.W.; project administration, S.A. and W.-K.W.; funding acquisition, J.P.O. and W.-K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available for sharing from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The fifth author would like to thank Robert B. Miller and Howard E. Thompson for their continuous guidance and encouragement. This research has been supported by National University of Science and Technology, Asia University, Air University, COMSATS University, China Medical University Hospital, The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong, Research Grants Council (RGC) of Hong Kong (project numbers 12502814 and 12500915), and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST, Project Numbers 106-2410-H-468-002 and 107-2410-H-468-002-MY3), Taiwan. However, any remaining errors are solely ours.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Jin, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, M. Does leadership matter in diversity management? Assessing the relative impact of diversity policy and inclusive leadership in the public sector. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Chung, B.G. Inclusive leadership: How leaders sustain or discourage work group inclusion. Group Organ. Manag. 2021, 47, 1059601121999580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanh Tran, T.B.; Choi, S.B. Effects of inclusive leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of organizational justice and learning culture. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2019, 13, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, A.; Wang, D.; Javed, B.; Zaffar, M.A. Moving beyond the mechanistic structures: The role of inclusive leadership in developing change-oriented organizational citizenship behaviour. Can. J. Adm. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. L’Administration 2021, 38, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Inclusive leadership and employee outcomes: A meta-analytic test of multiple theories. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2022, 2022, 16089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randel, A.E.; Galvin, B.M.; Shore, L.M.; Ehrhart, K.H.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Kedharnath, U. Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, M.Y. Creating a culture of inclusion and belongingness in remote work environments that sustains meaningful work. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 25, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Luna, M.; Reyes, D.L.; Traylor, A.; Lacerenza, C.N.; Salas, E. How to be an inclusive leader for gender-diverse teams. Organ. Dyn. 2022, 2022, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Kolbe, M.; Grote, G.; Spahn, D.R.; Grande, B. We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.; Cho, A.; Chang, W. Conceptualizing meaningful work and its implications for HRD. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 45, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluney, C.L.; Rabelo, V.C. Conditions of visibility: An intersectional examination of Black women’s belongingness and distinctiveness at work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 113, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canlas, A.L.; Williams, M.R. Meeting belongingness needs: An inclusive leadership practitioner’s approach. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2022, 24, 15234223221118953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A.V.; van Engen, M.L.; Knappert, L.; Schalk, R. About and beyond leading uniqueness and belongingness: A systematic review of inclusive leadership research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 32, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.; Asselin, H.; Beaudoin, J.-M.; Muresanu, D. Promoting perceived insider status of indigenous employees. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 26, 609–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pérez, F.; Lleo, A.; Ormazabal, M. Employee sustainable behaviors and their relationship with Corporate Sustainability: A Delphi study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clipa, A.-M.; Clipa, C.-I.; Danileț, M.; Andrei, A.G. Enhancing sustainable employment relationships: An empirical investigation of the influence of trust in employer and subjective value in employment contract negotiations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon-Roldan, F.; Lopez-Cabrales, A. The impact of employment relationships on firm sustainability. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2022, 44, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembhard, I.M.; Edmondson, A.C. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 941–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, E. Inclusive Leadership the Essential Leader-Follower Relationship; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ashikali, T.; Groeneveld, S.; Kuipers, B. The role of inclusive leadership in supporting an inclusive climate in diverse public sector teams. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2021, 41, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakari, H.; Hunjra, A.I.; Jaros, S.; Khoso, I. Moderating role of cynicism about organizational change between authentic leadership and commitment to change in Pakistani public sector hospitals. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2019, 32, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Liu, B.; Wei, X.; Hu, Y. Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, D.; Guo, W. Inclusive leadership and team innovation: The role of team voice and performance pressure. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamper, C.L.; Masterson, S.S. Insider or outsider? how employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, S.S.; Stamper, C.L. Perceived organizational membership: An aggregate framework representing the employee-organization relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chu, X.; Ni, J. Leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behavior: A new perspective from perceived insider status and Chinese traditionality. Front. Bus. Res. China 2010, 4, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ding, C.G.; Shen, C.-K. Perceived organizational support, participation in decision making, and perceived insider status for contract workers. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bakari, H.; Niaz, M.; Zhang, Q.; Shah, I.A. Impact of managerial trustworthy behavior on employee engagement: Mediating role of perceived insider status. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, J.R.; Smith, B.R.; Sprinkle, T.A. Clarifying the relational ties of organizational belonging. J. Leadersh. Organ. Studies 2014, 21, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapalme, M.-È.; Stamper, C.L.; Simard, G.; Tremblay, M. Bringing the outside in: Can “external” workers experience insider status? J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 919–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Aryee, S. Delegation and employee work outcomes: An examination of the cultural context of mediating processes in China. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M.E.M. Managing Diversity: Toward a Globally Inclusive Workplace; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 77, pp. 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, S.; Sylvestre, J.; Muresanu, D. Pro-diversity practices and perceived insider status. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 20, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O. Authentic leadership theory, research and practice: Steps taken and steps that remain. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Day, D.V., Ed.; Oxford Library of Psychology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 331–356. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C. When Diversity Training Isn’t Enough: The Case for Inclusive Leadership; Penn State Schuylkill: Schuylkill Haven, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Inclusive leadership, leader identification and employee voice behavior: The moderating role of power distance. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Naqvi, S.M.M.R.; Khan, A.K.; Arjoon, S.; Tayyeb, H.H. Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of psychological safety. J. Manag. Organ. 2017, 25, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, M.; Schlosser, F. Perceived organizational membership and the retention of older workers. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.; Lee, C.; Wang, H. Organizational inducements and employee citizenship behavior: The mediating role of perceived insider status and the moderating role of collectivism. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, M.P.; Near, J.P.; Dworkin, T.M. A word to the wise: How managers and policy-makers can encourage employees to report wrongdoing. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.J.; Sutcliffe, K.; Christianson, M. Speaking up and speaking out: The leadership dynamics of voice in organizations. In Voice and Silence in Organizations; Greenberg, J., Edwards, M.S., Eds.; Emerald Group: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hirak, R.; Peng, A.C.; Carmeli, A.; Schaubroeck, J.M. Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenkci, A.T.; Bircan, T.; Zimmerman, J. Inclusive leadership and work engagement: The mediating role of procedural justice. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 44, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, X. Procedural justice and employee engagement: Roles of organizational identification and moral identity centrality. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A. Understanding procedural justice and its impact on business organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chen, Z.X.; Budhwar, P.S. Exchange fairness and employee performance: An examination of the relationship between organizational politics and procedural justice. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2004, 94, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Prehar, C.A.; Chen, P.Y. Using social exchange theory to distinguish procedural from interactional justice. Group Organ. Manag. 2002, 27, 324–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizatioanl justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 424–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, J.B. The effect of organizational justice, perceived organizational support, and perceived supervisor support on marketing employees’ level of trust. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampa, J.; Rigotti, T.; Otto, K. Mechanisms linking authentic leadership to emotional exhaustion: The role of procedural justice and emotional demands in a moderated mediation approach. Ind. Health 2017, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quratulain, S.; Khan, A.K.; Sabharwal, M. Procedural fairness, public service motives, and employee work outcomes: Evidence from pakistani public service organizations. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2019, 39, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaola, P.; Coldwell, D. Explaining how leadership and justice influence employee innovative behaviours. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Charash, Y.; Spector, P.E. The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 278–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Moon, J.; Shin, J. Justice perceptions, perceived insider status, and gossip at work: A social exchange perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Matloob, S.; Abdul Rahim, N.F.; Abdul Halim, H.; Khattak, A.; Ahmed, N.H.; Nayab, D.E.; Hakeem, A.; Zubair, M. Factors impeding health-care professionals to effectively treat coronavirus disease 2019 patients in Pakistan: A qualitative investigation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 572450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakari, H.; Hunjra, A.I.; Niazi, G.S.K. How does authentic leadership influence planned organizational change? The role of employees’ perceptions: Integration of theory of planned behavior and lewin’s three step model. J. Change Manag. 2017, 17, 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, P.J.G.; Van Iersel-Van Silfhout, I.J. Job stress, job strain, and psychological withdrawal among Dutch university staff: Towards a dualprocess model for the effects of occupational stress. Work Stress 2001, 15, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet”—Retrospective observations and recent advances. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2022, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmann, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revicki, D. Internal Consistency Reliability. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3305–3306. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Advances in International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.S.; Wiechmann, D.; Ryan, A.M. Consequences of organizational justice expectations in a selection system. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Tang, N. Power distance orientation and perceived insider status in China: A social identity perspective. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2022, 28, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Hu, D.-C.; Liu, C.-H. The role of perceived insider status in employee creativity: Developing and testing a mediation and three-way interaction model. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 21, S53–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, M.R.; Oc, B. When voice matters: A multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. J. Manag. 2014, 41, 1530–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O.; Lam, C.K.; Huang, X. Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The moderating roles of distributive justice and positive affect. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 31, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Judge, T.A.; Shaw, J.C. Justice and personality: Using integrative theories to derive moderators of justice effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2006, 100, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadi, M.Y.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. Transformational leadership and work engagement. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bakari, H.; Hunjra, A.I.; Jaros, S. Gender and followership in a Pakistani context: How do men and women differ on their perception of authentic leadership. In Proceedings of the Southwest Academy of Management (SWAM), Houston, TX, USA, 13–16 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-P.; Wang, Y.-M.; Liu, N.-T.; Chen, Y.-L. Assessing turnover intention and the moderation of inclusive leadership: Training and educational implications. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 33, 1510–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Altantsetseg, P.; Mou, W.M.; Wong, W.K. Organizational Climate and Work Style: The Missing Links for Sustainability of Leadership and Satisfied Employees. Sustainability 2019, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arokiasamy, A.R.A.; Rizaldy, H.; Qiu, R. Exploring the impact of authentic leadership and work engagement on turnover intention: The moderating role of job satisfaction and organizational size. Adv. Decis. Sci. 2022, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.K.; Sriphon, T. The relationships among authentic leadership, social exchange relationships, and trust in organizations during COVID-19 pandemic. Adv. Decis. Sci. 2022, 26, 31–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lok, C.L.; Chuah, S.F.; Hooy, C.W. The Impacts of Data-Driven Leadership in IR4.0 adoption on firm performance in Malaysia. Ann. Financ. Econ. 2022, 17, 2250023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminah, H.; Moslehpour, M.; Rizaldy, H.; Batchuluun, S.; Sulistiawan, J. Understanding the Linear and Curvilinear Influences of Job Satisfaction and Tenure on Turnover Intention of Public Sector Employees in Mongolia. Adv. Decis. Sci. 2022, 26, 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Suu, N.D.; Tien, H.T.; Wong, W.K. The impact of capital structure and ownership on the performance of state enterprises after equitization: Evidence from Vietnam. Ann. Financ. Econ. 2021, 16, 2150007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkh-Ulzii, B.; McAleer, M.; Moslehpour, M.; Wong, W.K. Confucius and Herding Behaviour in the Stock Markets in China and Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirer, R.; Gupta, R.; Lv, Z.H.; Wong, W.K. Equity Return Dispersion and Stock Market Volatility: Evidence from Multivariate Linear and Nonlinear Causality Tests. Sustainability 2019, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.W.W.; Chow, N.S.C.; Chui, D.K.H.; Wong, W.K. The Three Musketeers relationships between Hong Kong, Shanghai and Shenzhen before and after Shanghai–Hong Kong Stock Connect. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.J.; Vieito, J.P.; Clark, E.; Wong, W.K. Could Mergers Become More Sustainable? A Study of the Stock Exchange Mergers of NASDAQ and OMX. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S.M.; Gilal, M.A.; Wong, W.K. Sustainability of Global Economic Policy and Stock Market Returns in Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Zada, H.; Yousaf, I. Does premium exist in the stock market for labor income growth rate? A six-factor-asset-pricing model: Evidence from Pakistan. Ann. Financ. Econ. 2022, 17, 2250017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, S.; Rasool, T.; Awan, T.; Rashid, A.; Wong, W.K. Birds of a Feather Flocking Together: Sustainability of Tax Aggressiveness of Shared Directors from Coercive Isomorphism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, G.-R.; McAleer, M.; Wong, W.K. Specification Testing of Production in a Stochastic Frontier Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Pham, V.K.; Wong, W.-K.; Bilgiçli, İ. e-Purchase Intention of Taiwanese Consumers: Sustainable Mediation of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use. Sustainability 2018, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Chaiyapruk, P.; Faez, S.; Wong, W.K. Generation Y’s Sustainable Purchasing Intention of Green Personal Care Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Lv, Z.H.; Wong, W.K. Macroeconomic Shocks and Changing Dynamics of the U.S. REITs Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Lean, H.H.; Ahmad, Z.; Wong, W.K. The impact of market condition and policy change on the sustainability of intra-industry information diffusion in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Vuong, T.H.G.; Nguyen, T.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Wong, W.K. Sustainability of Both Pecking Order and Trade-off Theories in Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjoub, H.; Odugbesan, A.; Adebayo, T.S.; Wong, W.K. Investigating the Causal Relationships among Carbon Emissions, Economic Growth, and Life Expectancy in Turkey: Evidence from Time and Frequency Domain Causality Techniques. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Awosusi, A.A.; Odugbesan, J.A.; Akinsola, G.D.; Wong, W.K.; Rjoub, H. Sustainability of Energy-induced Growth nexus in Brazil: Do CO2 Emissions and Urbanization matter? Sustainability 2021, 13, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wu, Y.C.; Wong, W.K. The Sustainability of Energy Substitution on the Chinese Electric Power Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.K.; Lean, H.H.; McAleer, M.; Tsai, F.T. Why are Warrant Markets Sustained in Taiwan but not in China? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Li, X.G.; Hui, Y.C.; Wong, W.K. Maslow Portfolio Selection for Individuals with Low Financial Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsendsuren, S.; Chu-Shiu Li, C.S.; Peng, S.C.; Wong, W.K. The Effects of Health Status on Life Insurance Holdings in 16 European Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, W.M.; Wong, W.K.; McAleer, M. Financial Credit Risk Evaluation Based on Core Enterprise Supply Chains. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Tang, J.; Wong, W.K.; Sriboonchitta, S. Modeling Co-Movement among Different Agricultural Commodity Markets: A Copula-GARCH Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnou-Laaroussi, S.; Rjoub, H.; Wong, W.K. Sustainability of Green Tourism among International Tourists and Its Influence on the Achievement of Green Environment: Evidence from North Cyprus. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjoub, H.; Odugbesan, A.; Adebayo, T.S.; Wong, W.K. Sustainability of the moderating role of Financial Development in the Determinants of Environmental Degradation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).