Dimensionality of Environmental Values and Attitudes: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Value Orientation

- Value is about the concept or beliefs;

- Value is about desirable end states or behaviors;

- Value transcends specific situations;

- Value guides the selection or evaluation of persons, behavior, and events;

- Value is ordered by relative importance.

2.1.1. Conceptualization of Value Orientations

2.1.2. Dimensionality of Environmental Values

2.2. Attitudes

2.2.1. Environmental Attitudes

2.2.2. New Ecological Paradigm Scale (NEP)

2.2.3. Dimensionality of Environmental Attitude Using NEP Scale

3. Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behaviour how to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L. Psychology of Environmental Attitudes: A Cross-Cultural Study of Their Content and Structure. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Grieneeks, J.K.; Rokeach, M. Human Values and Pro-Environmental Behavior. In Energy and Material Resources: Attitudes, Values, and Public Policy; Conn, W.D., Ed.; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1983; pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S. Understanding green purchase: The influence of collectivism, personal values and environmental attitudes, and the moderating effect of perceived consumer effectiveness. Seoul J. Bus. 2011, 17, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Kalof, L.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. Values, beliefs, and pro-environmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amburgey, J.W.; Thoman, D.B. Dimensionality of the new ecological paradigm issues of factor structure and measurement. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J.; Wagner, C. The higher order structure of environmental attitudes: A cross-cultural examination. Interam. J. Psychol. 2010, 44, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harring, N.; Jagers, S.C. Should we trust in values? Explaining public support for pro-environmental taxes. Sustainability 2013, 5, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saris, W.E.; Knoppen, D.; Schwartz, S.H. Operationalising the theory of human values: Balancing homogeneity of reflective items and theoretical coverage. Surv. Res. Methods 2012, 7, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value orientations and environmental beliefs in five countries validity of an instrument to measure egoistic, altruistic and biospheric value orientations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, M.; Verkasalo, M. Measuring values with the short Schwartz’s value survey. J. Personal. Assess. 2005, 85, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Kalof, L.; Stern, P.C. Gender, values, and environmentalism. Soc. Sci. Q. 2002, 83, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. A brief inventory of values. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1998, 58, 984–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansla, A.; Gamble, A.; Juliusson, A.; Gärling, T. The relationships between awareness of consequences, environmental concern, and value orientations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.G.; Cuervo-Arango, M.A. Relationship among values, beliefs, norms and ecological behaviour. Psicothema 2008, 20, 623–629. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L.; Dicke, M. Morality and reducing car use: Testing the norm activation model of prosocial behaviour. In Transportation Research Trends; Columbus, F., Ed.; NOVA Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J. The structure of environmental attitudes: A first-and second-order confirmatory factor analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Walker, G.J.; Swinnerton, G. A comparison of environmental values and attitudes between Chinese in Canada and Anglo-Canadians. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, S.C.; Juhl, H.J. Values, environmental attitudes, and buying of organic foods. J. Econ. Psychol. 1995, 16, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L. Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: Evidence for consistency across 14 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follows, S.B.; Jobber, D. Environmentally responsible purchase behaviour: A test of a consumer model. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi-Usui, M. How individual values affect green consumer behaviour? Results from a Japanese survey. Glob. Environ. Res. 2001, 5, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value structures behind pro-environmental behaviour. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Lee, J.W.C.; Mohamad, O. Green product purchase intention: Some insights from a developing country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I.; Drijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W.; Siero, F. General antecedents of environmental behaviour: Relationships between values, worldviews, environmental concern, and environmental behaviour. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L.; Keizer, M.; Farsang, A.; Watt, A. Environmental values in post-socialist Hungary: Is it useful to distinguish egoistic, altruistic and biospheric values? Czech Sociol. Rev. 2012, 48, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamar, M.; Wirawan, H.; Arfah, T.; Putri, R.P.S. Predicting pro-environmental behaviours: The role of environmental values, attitudes and knowledge. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2021, 32, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.A.; Thiault, L.; Beeden, A.; Beeden, R.; Benham, C.; Curnock, M.I.; Diedrich, A.; Gurney, G.G.; Jones, L.; Marshall, P.A.; et al. Our Environmental Value Orientations Influence How We Respond to Climate Change. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helm, S.; Serido, J.; Ahn, S.Y.; Ligon, V.; Shim, S. Materialist values, financial and proenvironmental behaviors, and well-being. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, A.; Ferguson, D. Unlocking consumers’ environmental value orientations and green lifestyle behavior. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2017, 9, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riper, C.; Winkler-Schor, S.; Foelske, L.; Keller, R.; Braito, M.; Raymond, C.; Eriksson, M.; Golebie, E.; Johnson, D. Integrating multi-level values and pro-environmental behavior in a US protected area. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1395–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Like father, like son? Intergenerational transmission of values, attitudes, and behaviours in the environmental domain. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel, R.H.; Newman, L.S. Increasing attitude-behaviour correspondence by broadening the scope of the behavioural measure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 33, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Jones, R.E. Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Dunlap, R.E., Michelson, W., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2002; pp. 482–524. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnappan, P.; Abd Rahman, A. Antecedents of green purchasing behaviour among Malaysian consumers. Int. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, N.A.; Rahbar, E.; Shyan, T.S. Factors influencing the green purchase behaviour of Penang environmental volunteers. Int. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K.S.; Muehlegger, E. Giving green to get green? Incentives and consumer adoption of hybrid vehicle technology. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J.; Jacob, J. Green Marketing: A Study of Consumers’ Attitude towards Environment Friendly Products. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. A proposed measuring instrument and preliminary results: The “New Environmental Paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.S.; Fielding, K.S. Environmental attitudes as WTP predictors: A case study involving endangered species. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 89, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peterson, M.N.; Hull, V.; Lu, C.; Lee, G.D.; Hong, D.; Liu, J. Effects of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental behaviour in urban China. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 38, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müderrisoðlu, H.; Altanlar, A. Attitudes and behaviours of undergraduate students toward environmental issues. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 8, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, M. Fifth Grade Students’ Environmental Literacy and the Factors Affecting Students’ Environmentally Responsible Behaviours. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, J. The new environmental paradigm and nature-based tourism motivation. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E. The New Environmental Paradigm. From marginality to worldwide use. J. Environ. Educ. 2002, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Willits, F.K. Environmental Attitudes and Behaviour A Pennsylvania Survey. Environ. Behav. 1994, 26, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, M.; Bogner, F.X. A higher-order model of ecological values and its relationship to personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.P. Oriental Disadvantage versus Occidental Exuberance Appraising Environmental Concern in India—A Case Study in a Local Context. Int. Sociol. 2008, 23, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P. Influence of sociodemographics and environmental attitudes on general responsible environmental behaviour among recreational boaters. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, C.C.; Johnson, B.; Dunlap, R.E. Assessing children’s environmental worldviews: Modifying and validating the New Ecological Paradigm Scale for use with children. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Bacon, D.R. Exploring the subtle relationships between environmental concern and ecologically conscious consumer behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, M. Education on marine mammal tours as agent for conservation—but do tourists want to be educated? Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2003, 46, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.C.; Tsurutani, T.; Lovrich, N.P.; Abe, T. Vanguards and rearguards in environmental politics a comparison of activists in Japan and the United States. Comp. Political Stud. 1986, 18, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S. Reliability and factor structure of a Korean version of the new environmental paradigm. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2001, 16, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C.W.-H.; Fryxell, G.E.; Wong, W.W.H. Effective regulations with little effect? The antecedents of the perceptions of environmental officials on enforcement effectiveness in China. Environ. Manag. 2006, 38, 388–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.S.; Poon, C.S. A comparison of waste-reduction practices and new environmental paradigm of rural and urban Chinese citizens. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 62, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawcroft, L.J.; Milfont, T.L. The impact of methodological features on measurement of cultural-level environmental attitudes: A meta-analysis. Aust. J. Psychol. 2008, 60, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde, R.; Jackson, E.L. The new environmental paradigm scale: Has it outlived its usefulness? J. Environ. Educ. 2002, 33, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, B.L.; Sockel, H. A confirmatory factor analysis of IS employee motivation and retention. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L.; Wothke, W. Amos 4.0 User’s Guide; SmallWaters Corporation: Chicago, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Scarpello, V. A longitudinal assessment of the determinant relationship between employee commitments to the occupation and the organization. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Lennox, R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, P.L. Role Conflict as Mediator of the Relationship between Total Quality Management Practices and Role Ambiguity. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, Malaysia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sureshchandar, G.S.; Rajendran, C.; Anantharaman, R.N. A holistic model for total quality service. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2001, 12, 378–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polderman, T.J.C.; Benyamim, B.; de Leeuw, C.A.; Sullivan, P.F.; Visscher, P.M.; Posthuma, D. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Dimensions (D) | Value Items | Country | Distinguished AV and BV (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stern et al. [7] | 4Ds (ST, SE, OT, T) | 34 | United States | No |

| Grunert and Juhl [23] | No Ds | 56 | Denmark | No |

| Stern et al. [17] | 4Ds (ST, SE, OT, T) | 34 | United States | No |

| Stern et al. [24] | 4Ds (ST, SE, OT, T) | 26 | United States | No |

| Schultz and Zelezny [25] | 10 value types | 37 | United States | No |

| Follows and Jobber [26] | 3Ds (ST. SE, T) | 11 | Canada | No |

| Aoyagi-Usui [27] | 3Ds (BV-T, AV, EV) | 12 | Japan | Yes |

| Dietz et al. [16] | 4Ds (SE, ST, OT, T) | 26 | United States | No |

| Nordland and Garvill [28] | 2Ds (SE, ST) | 24 | Sweden | No |

| Thøgersen and Ölander [29] | 5value types (SE, ST) | 16 | Denmark | No |

| Steg et al. [30] | 3Ds (EV, AV, BV) | 12 | Netherlands | Yes |

| Deng et al. [22] | 2Ds (AV, BV) | 10 | Canada | Yes |

| Milfont [2] | 2Ds (SE, AV) | 6 | New Zealand | No |

| de Groot et al. [20] | 3Ds (EV, AV, BV) | 13 | Austria, Czech Republic, Italy, Netherland, Sweden | Yes |

| de Groot and Steg [14] | 3Ds (EV, AV, BV) | 13 | Austria, Czech Republic, Italy, Netherland, Sweden | Yes |

| de Groot and Steg [1] | 3Ds (EV, AV, BV) | 13 | Netherlands | Yes |

| Ramayah et al. [31] | 3Ds (SE, ST, T) | 11 | Malaysia | No |

| Steg et al. [32] | 3Ds (EV, AV, BV) | 13 | Netherlands | Yes |

| Kim [4] | 2Ds (SE, ST) | 7 | Korea | No |

| Lopez-Mosquera and Sanchez [19] | 3Ds (EV, AV, BV) | 12 | Spain | Yes |

| de Groot et al. [33] | 3Ds (EV, AV, BV) | 13 | Hungary | Yes |

| Harring and Jagers [12] | 2Ds (EV, AV) | 9 | Sweden | No |

| Profile | Frequency (N = 500) | Percentage (100%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 282 | 56.4 |

| Male | 218 | 43.6 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 155 | 31 |

| 26–35 | 190 | 38 |

| 36–45 | 100 | 20 |

| 45–65 | 52 | 10.4 |

| 66 and above | 3 | 0.6 |

| Educational | ||

| High school | 60 | 12 |

| Certificate/Diploma | 109 | 21.8 |

| Bachelor degree | 272 | 54.4 |

| Postgraduate degree | 59 | 11.8 |

| Monthly income (RM) | ||

| Less than 1500 | 85 | 17 |

| 1501–3500 | 196 | 39.2 |

| 3501–5000 | 141 | 28.2 |

| 5001 and above | 78 | 15.6 |

| Occupational | ||

| Managerial level | 115 | 23 |

| Executive level | 169 | 33.8 |

| Clerical level | 38 | 7.6 |

| Housewife | 22 | 4.4 |

| Student | 156 | 31.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Malay | 111 | 22.2 |

| Chinese | 274 | 54.8 |

| Indian | 82 | 16.4 |

| Others | 33 | 6.6 |

| Items (V) | Mean | Standard Deviation | Items (EA) | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | 5.16 | 1.520 | EA1 | 5.05 | 1.192 |

| V2 | 5.17 | 1.434 | EA2 | 5.03 | 1.372 |

| V3 | 5.39 | 1.542 | EA3 | 5.26 | 1.324 |

| V4 | 5.53 | 1.533 | EA4 | 4.85 | 1.103 |

| V5 | 5.48 | 1.547 | EA5 | 5.40 | 1.329 |

| V6 | 5.47 | 1.496 | EA6 | 5.45 | 1.441 |

| V7 | 5.36 | 1.583 | EA7 | 5.46 | 1.354 |

| V8 | 5.58 | 1.491 | EA8 | 5.07 | 1.336 |

| - | - | - | EA9 | 5.25 | 1.289 |

| - | - | - | EA10 | 4.76 | 1.330 |

| - | - | - | EA11 | 5.26 | 1.309 |

| - | - | - | EA12 | 5.23 | 1.260 |

| - | - | - | EA13 | 5.15 | 1.176 |

| - | - | - | EA14 | 4.85 | 1.283 |

| - | - | - | EA15 | 5.59 | 1.281 |

| Overall mean score = 5.392 | Cronbach alpha = 0.947 | Overall mean score = 5.17 | Cronbach alpha = 0.916 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | KMO | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Eigenvalue | Total Variance Explained | Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Values (V) | V1 | 0.812 | 0.932 | 3600.854 *** | 5.862 | 73.277 | 0.947 |

| V2 | 0.856 | ||||||

| V3 | 0.890 | ||||||

| V4 | 0.836 | ||||||

| V5 | 0.892 | ||||||

| V6 | 0.856 | ||||||

| V7 | 0.812 | ||||||

| V8 | 0.888 | ||||||

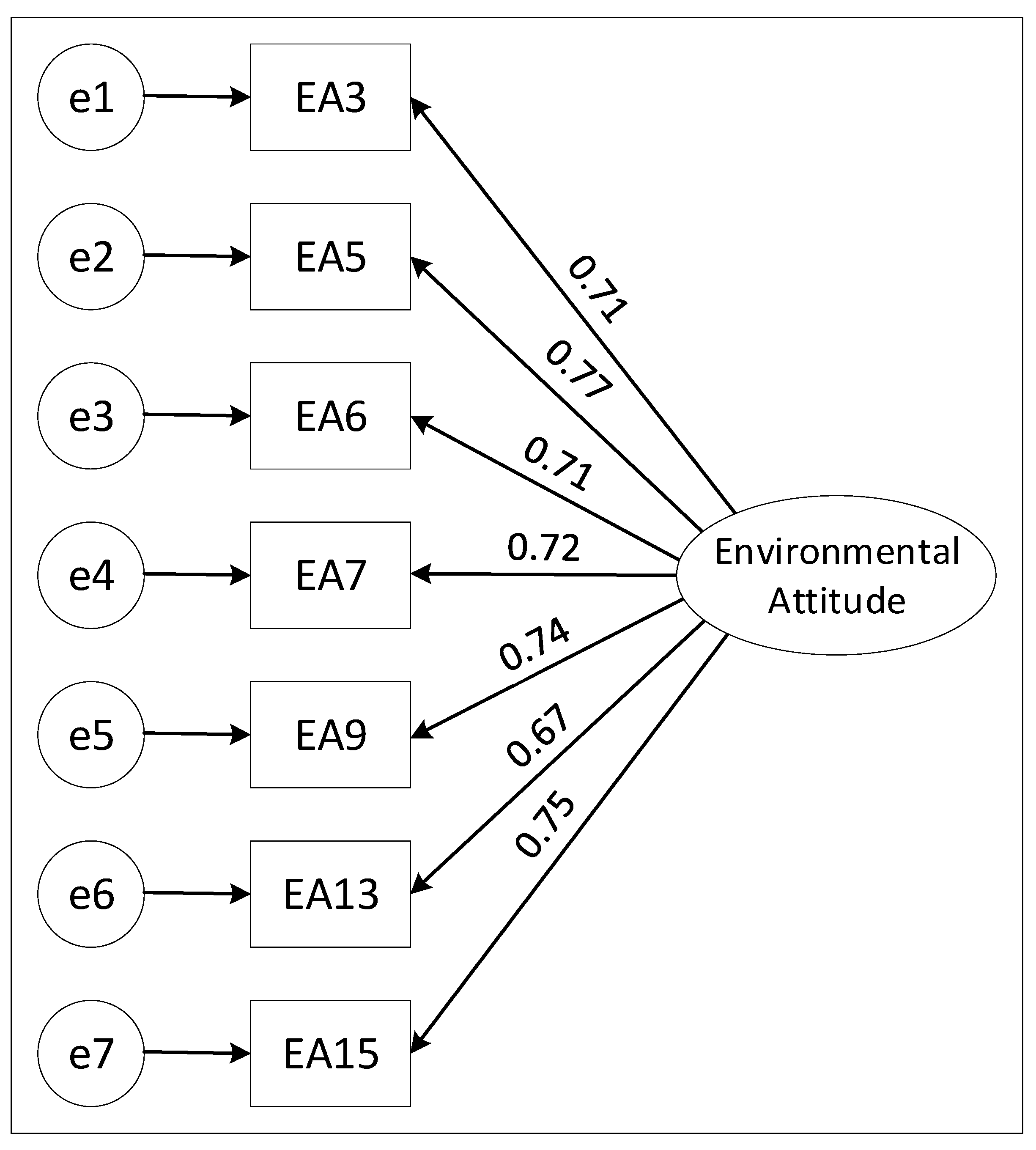

| Environmental Attitudes (EA) | EA3 | 0.761 | 0.922 | 1546.053 *** | 4.158 | 59.40 | 0.885 |

| EA5 | 0.807 | ||||||

| EA6 | 0.759 | ||||||

| EA7 | 0.768 | ||||||

| EA9 | 0.782 | ||||||

| EA13 | 0.724 | ||||||

| EA15 | 0.791 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Indices | Desirable Range | Original Measurement Model | Revised Measurement Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | <5 | 14.892 | 3.082 |

| GFI | >0.90 | 0.845 | 0.984 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.167 | 0.065 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.918 | 0.989 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.923 | 0.993 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.892 | 0.987 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Indices | Desirable Range | Original Measurement Model |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | <5 | 1.294 |

| GFI | >0.90 | 0.990 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.024 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.988 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.997 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.996 |

| Construct | Item | t-Value | Standardized Factor Loadings | Squared Standardized Factor Loadings/ SMC | Error Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Values (V) | V1 | - | 0.704 | 0.495 | 1.164 |

| V4 | 17.466 | 0.820 | 0.672 | 0.770 | |

| V5 | 19.297 | 0.916 | 0.840 | 0.383 | |

| V6 | 18.682 | 0.886 | 0.784 | 0.482 | |

| V7 | 16.954 | 0.795 | 0.632 | 0.920 | |

| V8 | 21.423 | 0.820 | 0.672 | 0.728 | |

| Total | Nil | 4.941 | 4.095 | 4.447 | |

| Squared of Total | Nil | 24.413 | Nil | Nil | |

| Composite Reliability = 24.413/(24.413 + 4.447) = 0.85, AVE = 4.095/6 = 0.69 | |||||

| Environmental Attitudes (EA) | EA3 | 15.635 | 0.715 | 0.511 | 0.856 |

| EA5 | 16.961 | 0.773 | 0.598 | 0.709 | |

| EA6 | 15.487 | 0.711 | 0.505 | 1.025 | |

| EA7 | 15.672 | 0.722 | 0.522 | 0.874 | |

| EA9 | 16.143 | 0.739 | 0.545 | 0.753 | |

| EA13 | 14.665 | 0.667 | 0.445 | 0.766 | |

| EA15 | - | 0.750 | 0.563 | 0.716 | |

| Total | Nil | 5.077 | 3.689 | 5.699 | |

| Squared of Total | Nil | 25.775 | Nil | Nil | |

| Composite Reliability = 25.775/(25.775 + 5.699) = 0.82, AVE = 3.689/7 = 0.53 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, B.C.; Khan, N.; Lau, T.C. Dimensionality of Environmental Values and Attitudes: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114201

Tan BC, Khan N, Lau TC. Dimensionality of Environmental Values and Attitudes: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114201

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Booi Chen, Nasreen Khan, and Teck Chai Lau. 2022. "Dimensionality of Environmental Values and Attitudes: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114201

APA StyleTan, B. C., Khan, N., & Lau, T. C. (2022). Dimensionality of Environmental Values and Attitudes: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia. Sustainability, 14(21), 14201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114201