Enhancing Emotional Resilience in the Face of Climate Change Adversity: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

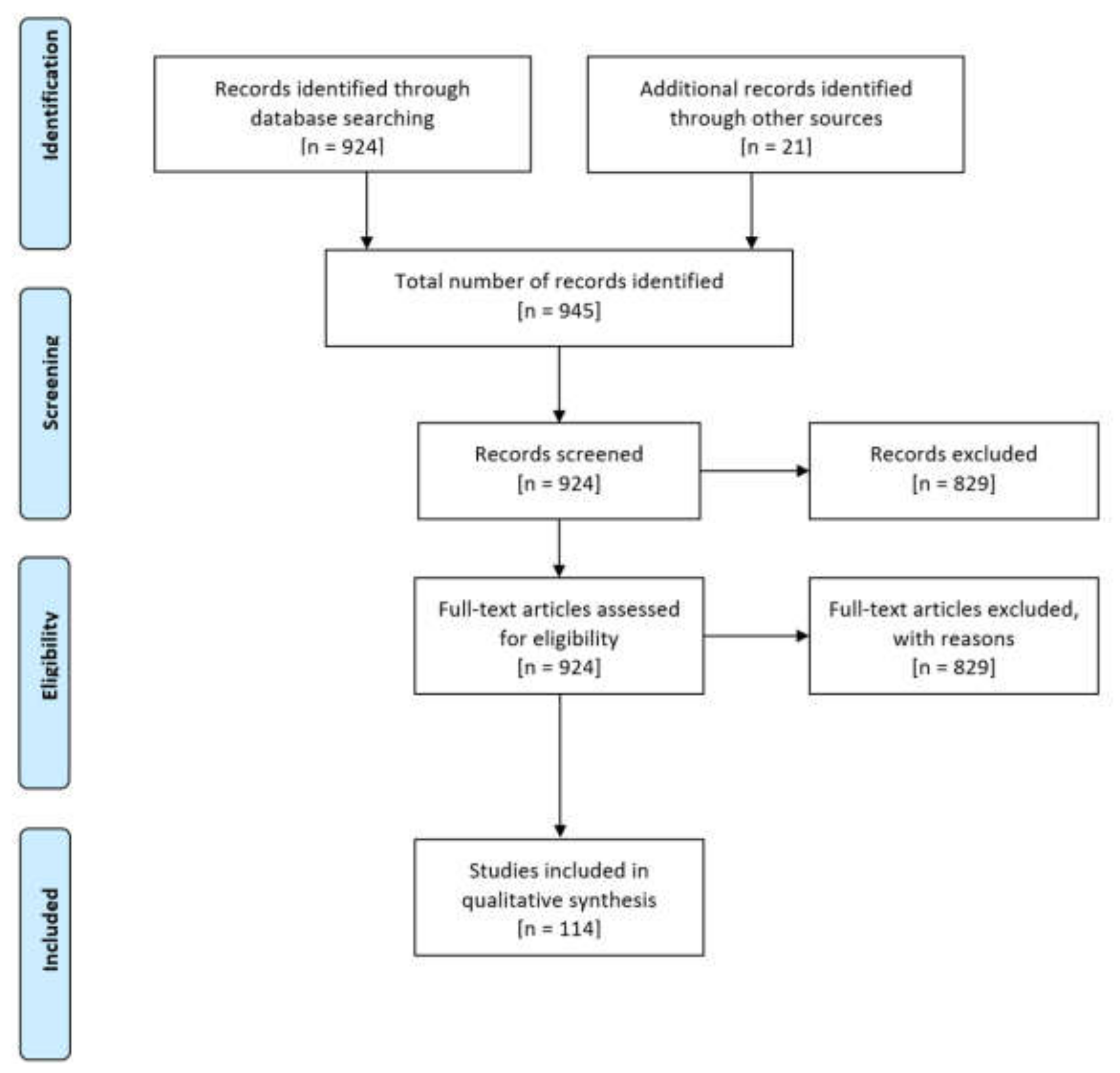

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Concepts

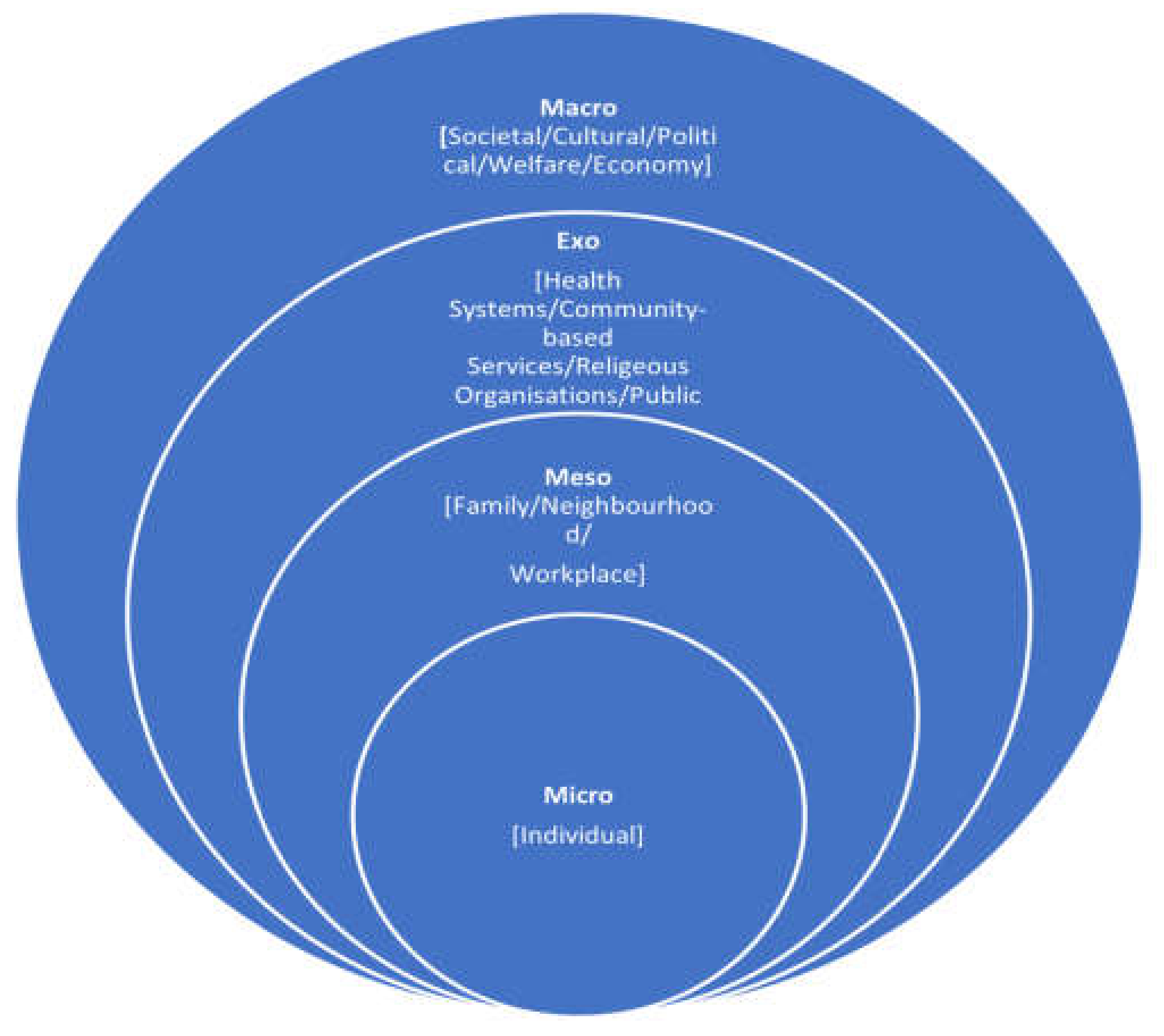

4.1.1. Bronfenbrenner’s Biological Theory of Development and Resilience

4.1.2. Emotional Resilience Concept

4.1.3. The Need to Understand the Development of Emotional Resilience

4.2. System Levels of Resilience: Individual and Community

4.3. Emotional Resilience-Enhancing Interventions

4.3.1. Individual-Level Interventions

4.3.2. Community-Level Interventions

4.4. Policy Considerations

4.4.1. Policy Realm 1: Community Preparedness

4.4.2. Policy Realm 2: Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments

4.4.3. Policy Realm 3: Collaboration among System Entities

4.4.4. Policy Realm 4: Community Engagement, Education, Communication, and Outreach

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy Recommendations

5.1.1. Communiy Preparedness

- Community preparedness recommendation 1: community relationship committeeEstablish principles and advisory material for a community relationship committee to undertake the following: (1) build cross-system partnerships; (2) identify appropriate tools to undertake vulnerability and adaptation assessments; (3) identify vulnerability risks and inform policy about perceived vulnerabilities, and (4) create appropriate communication, engagement, communication, education, and outreach systems for the target stakeholders, community members. and other affected populations.

- Community preparedness recommendation 2: evaluation criteriaDevelop evaluation criteria, including ways of assessing social, economic, and environmental costs at individual, community, and government levels, to evaluate vulnerabilities, existing strengths and resources within these levels, and assess the accessibility of support services. Different methods may be applied to evaluate these costs, including a cost–benefit analysis of qualitative and quantitative data.

- Community preparedness recommendation 3: promotion principlesDevelop promotion principles that incorporate resilience-enhancing initiatives at the individual, community, and government levels. Examples could include the following at an individual level: recommendations for developing and implementing programs that encourage connection and access to support services:

- Programs that incorporate activities, sports, sports, and art to foster connection.

- Activities that support reflection, such as yoga, meditation, and mindfulness, to enhance resilience at the individual level through improved self-awareness.

- Grassroots programs that promote relationships and connections between people and places.

- Reducing barriers to support services can improve accessibility.

- Community preparedness recommendation 4: monitoring principleDevelop monitoring principles that include mental health impacts, and initiatives, programs and funding, and collaboration of system entities. Monitoring principles are essential to ensure that intervention and adaption strategies are appropriate and adaptable to meeting diverse needs across different communities. They are also beneficial in determining the wider impacts of these strategies on the broad sytem levels.

5.1.2. Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments

- Vulnerability and adaptation assessment recommendation 1: national system-wide principlesFirstly, developing principles for a national environmental health surveillance system that includes climate change-related indicators for mental health. Secondly, establish a community engagement committee to build cross-system partnerships. Finally, develop a training program for professionals (health, teachers, and relevant others) to recognize, prepare for, and respond to the mental health impacts of climate change.

- Vulnerability and adaptation assessment recommendation 2: evaluation principlesDevelop evaluation principles that include appraising social, economic, and environmental costs associated with the focus issue from the individual, community, and government levels, evaluating vulnerabilities, existing strengths, and resources within these levels, and assessing the accessibility of support services.

- Vulnerability and adaptation assessment recommendation 3: community preparednessWe discuss evaluation tools in Section 5.1.1, Community Preparedness.

- Vulnerability and adaptation assessment recommendation 4: promotion principlesDevelop promotion principles that incorporate resilience-enhancing initiatives at individual, community, and government levels and leadership avenues through a Climate Change Forum. This forum is based on the concept of interagency collaboration. Climate Change Forum participants should be cross-system stakeholders (inclusive of government representatives, community organizations, businesses), community members and other interested people, who can work collaboratively to support collaboration between system levels and inform ongoing decision-making processes. Great care should be taken to ensure representativeness in the Forum participants. Children and youth must be represented. We explain considerations of resilience-enhancing initiatives in Section 5.1.1, Community Preparedness.

- Vulnerability and adaptation assessment recommendation 5: monitoring principlesDevelop monitoring principles that include mental health impacts, reporting of evaluations, policy and interventions, and collaborations of system entities. The benefits of such monitoring principles are previously discussed in community preparedness recommendation 4: monitoring principles.

5.1.3. Community Engagement, Communication, Education, and Outreach

- Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach recommendation 1: community engagement committeeEstablish principles for establishing a community engagement committee to build cross-system partnerships and appropriate community engagement, education, communication, and outreach systems that reflect those described earlier in this section.Emphasize engagement of children, young people, adults, apolitical and nonaligned community leaders, people from diverse cultural, ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, policymakers, public health authorities, physical and mental health professionals, emergency professionals, environmental agencies, and meteorological services.

- Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach recommendation 2: evaluation principlesEstablish evaluation principles. Evaluation principles may include appraising social, economic, and environmental costs associated with the focus issue at individual, community, and government levels. Additional evaluation principles could include evaluating the vulnerabilities, strengths, and resources within these levels and collaboration of system entities. We discuss evaluation tools in Section 5.1.1, Community Preparedness.

- Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach recommendation 3: promotion principlesDevelop promotion principles that incorporate resilience-enhancing initiatives at in-dividual, community, and government levels. We discuss resilience-enhancing initiatives in Section 5.1.1 Community Preparedness.

- Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach recommendation 4: monitoring principlesDevelop monitoring principles. Monitoring principles include mental health impacts, all initiatives, programs, and funding, and collaboration of system entities. The benefits of such monitoring principles are previously discussed in community preparedness recommendation 4: monitoring principles and referred to in vulnerability and adaptation assessment recommendation 5: monitoring principles.

5.1.4. Collaboration of System Entities

- Collaboration of system entities recommendation 1: a national environmental health surveillance systemEstablish a national environmental health surveillance system that would involve climate change-related mental health indicators, a community engagement committee to build cross-system relationships and partnerships, and a training program for professionals to recognize, prepare for, and respond to the mental health impacts of climate change.

- Collaboration of system entities recommendation 2: evaluation principlesDevelop evaluation principles. Evaluation principles could include appraising social, economic, and environmental costs associated with the focus issue at the individual, community, and government levels. Additional evaluation principles include appraisal of current and future cost predictions and collaboration of system entities. We discuss evaluation tools in Section 5.1.1, Community Preparedness.

- Collaboration of system entities recommendation 3: promotion principlesDevelop promotion principles to incorporate resilience-enhancing initiatives at individual, community, and government levels. We discuss considerations of resilience-enhancing initiatives in Section 5.1.1, Community Preparedness.

- Collaboration of system entities recommendation 4: monitoring principlesDevelop monitoring principles that include mental health impacts, all initiatives, programs and funding, and collaboration of system entities. The benefits of such monitoring principles are previously discussed in community preparedness recommendation 4: monitoring principles and referred to in vulnerability and adaptation assessment recommendation 5: monitoring principles and Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach recommendation 4: monitoring principles.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nuttman-Shwartz, O. Behavioral Responses in Youth Exposed to Natural Disasters and Political Conflict. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettinga, N.; Jacquet, P.O.; André, J.-B.; Baumand, N.; Chevallier, C. Environmental Adversity Is Associated with Lower Investment in Collective Actions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C; IPCC: Genève, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T.; Jones-Casey, K.; Tasala, K. Mapping the Solastalgia Literature: A Scoping Review Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan-Rankin, S. Self-Identity, Embodiment and the Development of Emotional Resilience. Br. J. Soc. Work 2014, 44, 2426–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Solastalgia. Altern. J. 2006, 32, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, J.; Johnstone, C. Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in without Going Crazy; New World Library: Novato, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T.C. Flourishing Across Europe: Application of a New Conceptual Framework for Defining Well-Being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D. The Construct of Resilience: Implications for Interventions and Social Policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 857–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macy, J. Breathing Through the Pain of the World. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1984, 24, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, L. Resilience: How to Cope When Everything around You Keeps Changing; Capstone/John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, D. Disaster in Relation to Attachment, to Community, and to Place: The Marysville Experience; RMIT: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The Distress Caused by Environmental Change. Australas. Psychiatry 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, C.R. Cognitive Processing of Adverse Experiences. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 1996, 8, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, A.; Tanton, R.; Lockie, S.; May, S. Focusing Resource Allocation-Wellbeing as a Tool for Prioritizing Interventions for Communities at Risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3435–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E.; Peterson, G.D.; Wilkinson, C.; Fünfgeld, H.; McEvoy, D.; Porter, L. Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? “Reframing” Resilience: Challenges for Planning Theory and Practice Interacting Traps: Resilience Assessment of a Pasture Management System in Northern Afghanistan Urban Resilience: What Does It Mean in Planni. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Adoption of the Paris Agreement; UNFCC: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, F.; Horsburgh, N.; Mulvenna, V. Framework for a National Strategy on Climate, Health and Well-Being for Australia; Climate and Health Alliance: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental Health Services in Australia. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/expenditure-on-mental-health-related-services (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Department of Health. Climate Health WA Inquiry Final Report; Department of Health, Government of Western Australia: Perth, WA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett, S.; Swerissen, H. A Redesign Option for Mental Health Care: Submission to Productivity Commission Review of Mental Health. 2020. Available online: https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Grattan-Inst-sub-mental-health.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Ponniah, S.; Angus, D.; Babbage, S. Mental Health in the Age of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.pwc.com.au/health/health-matters/why-mental-health-matters-covid-19.html (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Cohen, P.A. Bringing Research into Practice. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 1990, 1990, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, H.J.; Cottrell, A.; King, D.; Stevenson, R.B.; Millar, J. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory for Modelling Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Nat. Hazards 2012, 60, 381–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C.; Bober, T. Building a Framework: Health, Stress, Crisis and Trauma. In The Line Of Fire: Trauma In The Emergency Services; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weems, C.F.; Watts, S.E.; Marsee, M.A.; Taylor, L.K.; Costa, N.M.; Cannon, M.F.; Carrion, V.G.; Pina, A.A. The Psychosocial Impact of Hurricane Katrina: Contextual Differences in Psychological Symptoms, Social Support, and Discrimination. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastri, P. Resilience: Building Immunity in Psychiatry. Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whaley, A.L. Trauma Among Survivors of Hurricane Katrina: Considerations and Recommendations for Mental Health Care. J. Loss Trauma 2009, 14, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Bonanno, G.A.; Masten, A.S.; Panter-Brick, C.; Yehuda, R. Resilience Definitions, Theory, and Challenges: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 25338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Feder, A.; Cohen, H.; Kim, J.; Calderon, S.; Charney, D.; Mathé, A. Understanding Resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.I. Complex Trauma: Approaches to Theory and Treatment. J. Loss Trauma 2006, 11, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnano, G. Loss, Trauma and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive after Extremely Aversive Events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, S.R.; Charney, D.S.; Feder, A. Understanding Resilience: New Approaches for Preventing and Treating PTSD. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 284, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, M.W.G.; van der Velden, P.G. Longitudinal Interplay between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Coping Self-Efficacy: A Four-Wave Prospective Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 134, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbin, A.; Ross, S. How Memory Structures Influence Distress and Recovery. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knežević, M.; Krupić, D.; Šućurović, S. Emotional Competence and Combat-Related PTSD Symptoms in Croatian Homeland War Veterans. Drus. Istraz. 2017, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y. The Essential Resilience Scale: Instrument Development and Prediction of Perceived Health and Behaviour. Stress Health 2016, 32, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiller, T.R.; Liddell, B.J.; Schick, M.; Morina, N.; Schnyder, U.; Pfaltz, M.; Bryant, R.A.; Nickerson, A. Emotional Reactivity, Emotion Regulation Capacity, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Traumatized Refugees: An Experimental Investigation. J. Trauma Stress 2019, 32, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Dowd, A.-M.; Gaillard, E.; Park, S.; Howden, M. “Climate Change Is the Least of My Worries”: Stress Limitations on Adaptive Capacity. Rural. Soc. 2015, 24, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremeans-Smith, J.K.; Greene, K.; Delahanty, D.L. Trauma History as a Resilience Factor for Patients Recovering from Total Knee Replacement Surgery. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Mancini, A.D. The Human Capacity to Thrive in the Face of Potential Trauma. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wymbs, N.F.; Orr, C.; Albaugh, M.D.; Althoff, R.R.; O’Loughlin, K.; Holbrook, H.; Garavan, H.; Montalvo-Ortiz, J.L.; Mostofsky, S.; Hudziak, J.; et al. Social Supports Moderate the Effects of Child Adversity on Neural Correlates of Threat Processing. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 102, 104413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.M.; Vernberg, E.M. Part 1: Children’s Psychological Responses to Disasters. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1993, 22, 464–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, J.; Mittal, M.; Wieling, E. Linking Human Systems: Strengthening Individuals, Families, And Communities in the Wake of Mass Trauma. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2008, 34, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, H. Informal Sports for Youth Recovery: Grassroots Strategies in Conflict and Disaster Geographies. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 708–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsac, M.L.; Kassam-Adams, N. A Novel Adaptation of a Parent–Child Observational Assessment Tool for Appraisals and Coping in Children Exposed to Acute Trauma. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2016, 7, 31879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, J. Preparing for and Responding to Disasters. In Crisis Counseling, Intervention and Prevention in the Schools; Sandoval, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 229–241. ISBN 9781136506918. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, E.E. Children and War: Risk, Resilience, and Recovery. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisner, B.; Paton, D.; Alisic, E.; Eastwood, O.; Shreve, C.; Fordham, M. Communication With Children and Families About Disaster: Reviewing Multi-Disciplinary Literature 2015–2017. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, M.; Young, S.Y.; Harvey, J.; Rosenstein, D.; Seedat, S. An Examination of Differences in Psychological Resilience between Social Anxiety Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Context of Early Childhood Trauma. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.-M.; Stone, L. Adult Survivors of Childhood Trauma: Complex Trauma, Complex Needs. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ager, A. Annual Research Review: Resilience and Child Well-Being Public Policy Implications. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, C. “Sailing through a River of Emotions”: Capturing Children’s Earthquake Stories. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2013, 22, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halligan, S. How Can Informal Support Impact Child PTSD Symptoms Following a Psychological Trauma? Emerg. Med. J. 2017, 34, A894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.S.; Perry, K.-M.E. Like a Fish Out of Water: Reconsidering Disaster Recovery and the Role of Place and Social Capital in Community Disaster Resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. A Conceptual Framework for Measuring Livelihood Resilience: Relocation Experience from Aceh, Indonesia. World Dev. 2019, 117, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, M.R.; Lee, M.R.; Slack, T.; Blanchard, T.C.; Carney, J.; Lipschitz, F.; Gikas, L. Geographically Distant Social Networks Elevate Perceived Preparedness for Coastal Environmental Threats. Popul. Environ. 2018, 39, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getanda, E.M.; Vostanis, P. Feasibility Evaluation of Psychosocial Intervention for Internally Displaced Youth in Kenya. J. Ment. Health 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupavac, V. Psychosocial Interventions and the Demoralization of Humanitarianism. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2004, 36, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ida, D.J. Cultural Competency and Recovery within Diverse Populations. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2007, 31, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioneso, N.A.; Hunter, C.D.; Gobin, R.L.; McNeil Smith, S.; Mendenhall, R.; Neville, H.A. Community Healing and Resistance Through Storytelling: A Framework to Address Racial Trauma in Africana Communities. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FCAP 2015. Transl. Dev. Psychiatry 2015, 3, 29697. [CrossRef]

- Kamara, J.K.; Sahle, B.W.; Agho, K.E.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Governments’ Policy Response to Drought in Eswatini and Lesotho: A Systematic Review of the Characteristics, Comprehensiveness, and Quality of Existing Policies to Improve Community Resilience to Drought Hazards. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2020, 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.; Colo, E. Psychosocial Peacebuilding in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Intervention 2014, 12, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, R. Women’s Voices: Solace and Social Innovation in the Aftermath of the 2010 Christchurch Earthquakes. Women’s Stud. J. 2015, 29, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, S. Nature Trauma: Ecology and the Returning Soldier in First World War English and Scottish Fiction, 1918–1932. J. Med. Humanit. 2021, 42, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arel, S. The Power of Place : Trauma Recovery and Memorialization. Stellenbosch Theol. J. 2018, 4, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, I.G.; Tyrnov, O.F. The Effect of Solar Activity on Ill and Healthy People under Conditions of Neurous and Emotional Stresses. Adv. Space Res. 2001, 28, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkstrand, J.; Schiller, D.; Li, J.; Davidson, P.; Rosén, J.; Mårtensson, J.; Kirk, U. The Effect of Mindfulness Training on Extinction Retention. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushing, H. Peace Profile: Dunna. Peace Rev. 2019, 31, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C.J.; Hooven, C. Interoceptive Awareness Skills for Emotion Regulation: Theory and Approach of Mindful Awareness in Body-Oriented Therapy (MABT). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovissi, M.; Hagaman, H. Trauma-Informed Educational Yoga Program for Teens as an Addiction Prevention Tool. World Med. Health Policy 2020, 12, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.C.; Szabo, Y.Z.; Frankfurt, S.B.; Kimbrel, N.A.; DeBeer, B.B.; Morissette, S.B. Predictors of Recovery from Post-Deployment Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in War Veterans: The Contributions of Psychological Flexibility, Mindfulness, and Self-Compassion. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 114, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, S. Toward a Jamesian Account of Trauma and Healing. Philos. Inq. 2017, 5, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Bae, G.Y.; Rim, H.-D.; Lee, S.J.; Chang, S.M.; Kim, B.-S.; Won, S. Mediating Effect of Resilience on the Association between Emotional Neglect and Depressive Symptoms. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.P.; Hartelius, G. Resolution of Dissociated Ego States Relieves Flashback-Related Symptoms in Combat-Related PTSD: A Brief Mindfulness Based Intervention. Mil. Psychol. 2020, 32, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastell, C.A. Exposure to Trauma: The Long-Term Effects of Suppressing Emotional Reactions. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2002, 190, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, H.P. Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler. Psychoanal. Study Child 2011, 65, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trundle, G.; Hutchinson, R. The Phased Model of Adventure Therapy: Trauma-Focussed, Low Arousal & Positive Behavioural Support. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2021, 21, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Wolfert, S.; Fahmy, P.; Nayyar, M.; Chaudhry, A. The Therapeutic Effects of Imagination: Investigating Mimetic Induction and Dramatic Simulation in a Trauma Treatment for Military Veterans. Arts Psychother. 2019, 62, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, S. Rhythm2Recovery: A Model of Practice Combining Rhythmic Music with Cognitive Reflection for Social and Emotional Health within Trauma Recovery. Aust. New Zealand J. Fam. Ther. 2017, 38, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirek, S.L. Narrative Reconstruction and Post-Traumatic Growth among Trauma Survivors: The Importance of Narrative in Social Work Research and Practice. Qual. Soc. Work. 2017, 16, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Douglas, K. Narrating Embodied Experience: Sharing Stories of Trauma and Recovery. Sport Educ. Soc. 2016, 21, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.A. Music Therapy and Chronic Mental Illness: Overcoming the Silent Symptoms. Music Ther. Perspect. 2015, 33, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, I. South African Music Learners and Psychological Trauma: Educational Solutions to a Societal Dilemma. J. Transdiscipl. Res. South. Afr. 2013, 9, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marlin-Curiel, S. The Long Road to Healing: From the TRC to TfD. Theatre Res. Int. 2002, 27, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.P.; Dobson, M. A General Model for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in War Veterans. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1995, 32, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.A. Building Shelter in a Chaotic World: The Role of Empathic Imagination in Recovery from Trauma. Psychoanal. Self Context 2019, 14, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Tennichi, H.; Kameoka, S.; Kato, H. Long-Term Psychological Recovery Process and Its Associated Factors among Survivors of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in Japan: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.; Berry, P.; Ebi, K.L. Factors Influencing the Mental Health Consequences of Climate Change in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, S.B.; Baker, C.K.; Mayer, J.; O’Donnell, C.R. Resilience and Recovery in American Sāmoa: A Case Study of the 2009 South Pacific Tsunami. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 42, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashoul-Andary, R.; Assayag-Nitzan, Y.; Yuval, K.; Aderka, I.M.; Litz, B.; Bernstein, A. A Longitudinal Study of Emotional Distress Intolerance and Psychopathology Following Exposure to a Potentially Traumatic Event in a Community Sample. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2016, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P.M.; Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S.; Kent, A.; Burgin, C.E.; Parker, D.E.; Hossain, A.; Jeon-Slaughter, H.; Trautman, R.P. Physiologic Reactivity Despite Emotional Resilience Several Years After Direct Exposure to Terrorism. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Sage, C.A.M.; Amlôt, R.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. Risk and Resilience Factors Affecting the Psychological Wellbeing of Individuals Deployed in Humanitarian Relief Roles after a Disaster. J. Ment. Health 2015, 24, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, C.; Vet, E. Untangling Insurance, Rebuilding, and Wellbeing in Bushfire Recovery. Geogr. Res. 2021, 59, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.A.; Deterding, N.M. The Emotional Cost of Distance: Geographic Social Network Dispersion and Post-Traumatic Stress among Survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 165, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.M.; Morozink Boylan, J.; van Reekum, C.M.; Lapate, R.C.; Norris, C.J.; Ryff, C.D.; Davidson, R.J. Purpose in Life Predicts Better Emotional Recovery from Negative Stimuli. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, S.; Cohen, O.; Aharonson-Daniel, L. The Contribution of Personal and Place-Related Attributes to the Resilience of Conflict-Affected Communities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzi, L.; Tronick, E. The Power of Disconnection during the COVID-19 Emergency: From Isolation to Reparation. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, S252–S254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B.H. A Personal–Professional Experience of Losing My Home to Wildfire: Linking Personal Experience with the Professional Literature. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2017, 45, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.; Elliott, S.; Williams, A. Space, Place and Mental Health; Ashgate E-Book: Farnham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yusa, A.; Berry, P.; Cheng, J.; Ogden, N.; Bonsal, B.; Stewart, R.; Waldick, R. Climate Change, Drought and Human Health in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 8359–8412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick-Smith, A.; Dahlberg, E.E.; Thompson, S.C. Systematic Review of Resilience-Enhancing, Universal, Primary School-Based Mental Health Promotion Programs. BMC Psychol. 2018, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutch, C.; Gawith, E. The New Zealand Earthquakes and the Role of Schools in Engaging Children in Emotional Processing of Disaster Experiences. Pastor. Care Educ. 2014, 32, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemtob, C.M.; Nakashima, J.P.; Hamada, R.S. Psychosocial Intervention for Postdisaster Trauma Symptoms in Elementary School Children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springgate, B.F.; Arevian, A.C.; Wennerstrom, A.; Johnson, A.J.; Eisenman, D.P.; Sugarman, O.K.; Haywood, C.G.; Trapido, E.J.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Everett, A.; et al. Community Resilience Learning Collaborative and Research Network (C-LEARN): Study Protocol with Participatory Planning for a Randomized, Comparative Effectiveness Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A. Survivance Confronts Collective Trauma with Community Response. Am. Q. 2018, 70, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, N.L.; Stokar, Y.N.; Ginat-Frolich, R.; Ziv, Y.; Abu-Jufar, I.; Cardozo, B.L.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; Brom, D. Building Resilience Intervention (BRI) with Teachers in Bedouin Communities: From Evidence Informed to Evidence Based. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 87, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisic, E.; Barrett, A.; Bowles, P.; Conroy, R.; Mehl, M.R. Topical Review: Families Coping With Child Trauma: A Naturalistic Observation Methodology. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Hawkins, C.V.; Rivera, F.I. Disaster Resiliency: Interdisciplinary Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S.; Orru, K.; Siibak, A.; Bäck, A.; Krüger, M.; Gabel, F.; Morsut, C. Communication-Related Vulnerability to Disasters: A Heuristic Framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Black, J.; Jones, M.; Wilson, L.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Astell-Burt, T.; Black, D. Flooding and Mental Health: A Systematic Mapping Review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, S.; Prince, M.; Sumathipala, A.; Siribaddana, S.; Morgan, C. “We Lost All We Had in a Second”: Coping with Grief and Loss after a Natural Disaster. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Words Identified in Title: | Enhancing | Emotional Resilience | Climate Change | Adversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative words identified: | Improving | Resilience | Environmental Degradation | Trauma |

| Developing | Resistance | Solastalgia | ||

| Cultivating | Flexibility | Difficulty | ||

| Supporting | Distress |

| Policy Considerations and Components | Summary of Themes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Preparedness | Aim for communities to possess emergency preparedness planning capabilities for climate change adversity and emotional wellbeing impacts. | Need for national emotional support strategies accessible at the community level. | May take the form of community support services. | Factor for consideration: accessibility measures to support services. |

| Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments | Aim to determine community vulnerabilities, strengths, and existing resources. | Develop assessment frameworks and strategies that consider contexts of vulnerability and risk. | May inform interventions and education processes at different systemic levels. | Factors for consideration: relate to context of vulnerability risk, using person-centred approaches to question, explore, and use storytelling about affected communities to humanize and inform policy and intervention strategies. |

| Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach | Aim to establish early and ongoing communication channels to support knowledge-building pathways. | May include community awareness and engagement programs. Can support minimising systematic vulnerabilities and building resilience. | Use community awareness and engagement programs, campaigns, media, and community/cultural events for multiple opportunities to engage and share knowledge. | Factors for consideration: cultural relevance and empathy. |

| Collaboration of System Entities | Aim to achieve connections among and within system levels | Need for adaptable policies to reflect diverse needs of entities in different communities | May include stakeholder and community engagement within policy identification, development, implementation, maintenance, and monitoring phases to ensure policies are appropriate and reflect the current population’s needs. | Factors for consideration: engaging populations with existing vulnerabilities. |

| Policy Consideration Components | Establish | Evaluate | Promote | Monitor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Preparedness | Community engagement committee to build relationships. | Social, economic, and environmental costs of climate change adversity upon mental health. | Resilience-enhancing initiatives at individual, community, and government levels. | Mental health impacts |

| Vulnerability and adaptation assessment systems. | Vulnerabilities, existing strengths, and existing resources. | Initiatives, programs, funding, etc. | ||

| Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach systems. | Accessibility of support services. | Collaboration of system entities. | ||

| Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments | National environmental health surveillance system that includes climate change-related indicators. Committee to build community relationships Training program for professionals to recognise, prepare for, and respond to mental health impacts of climate change. | Social, economic, and environmental costs of climate change adversity upon mental health. Current and future cost predictions. Vulnerabilities, existing strengths, and existing resources. Accessibility of support services. | Resilience-enhancing initiatives at individual, community, and government levels. Leadership through Climate Change Forum consisting of governance representatives, cross-system stakeholders, and community members. | Mental health impacts. Reporting of evaluations, policy, and interventions. Collaboration of system entities. |

| Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach | Committee to build stakeholder and other community relationships. Community engagement, communication, education, and outreach systems | Social, economic, and environmental costs of climate change adversity upon mental health. Vulnerabilities, existing strengths, and existing resources. Collaboration of system entities. | Resilience-enhancing initiatives from individual, community, and government levels. | Mental health impacts. Initiatives, programs, funding, etc. Collaboration of system entities. |

| Collaboration of System Entities | National environmental health surveillance system that includes climate change-related indicators. Committee to build stakeholder and other community relationships. Training program for professionals to recognise, prepare for, and respond to mental health impacts of climate change. | Social, economic, and environmental costs of climate change adversity upon mental health. Current and future cost predictions. Collaboration of system entities. | Resilience-enhancing initiatives from individual, community, and government levels. Leadership through establishing a Climate Change Forum consisting of governance representatives, cross-system stakeholders, and community members. | Mental health impacts. Reporting of evaluations, policy, and interventions Collaboration of system entities. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Easton-Gomez, S.C.; Mouritz, M.; Breadsell, J.K. Enhancing Emotional Resilience in the Face of Climate Change Adversity: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113966

Easton-Gomez SC, Mouritz M, Breadsell JK. Enhancing Emotional Resilience in the Face of Climate Change Adversity: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):13966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113966

Chicago/Turabian StyleEaston-Gomez, Shona C., Mike Mouritz, and Jessica K. Breadsell. 2022. "Enhancing Emotional Resilience in the Face of Climate Change Adversity: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 13966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113966

APA StyleEaston-Gomez, S. C., Mouritz, M., & Breadsell, J. K. (2022). Enhancing Emotional Resilience in the Face of Climate Change Adversity: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(21), 13966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113966