The Moderating Role of Personal Innovativeness in Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 Based on Updated Information Systems Success Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Web 3.0

2.2. Benefits of Applying Web 3.0 Technology in Tourism

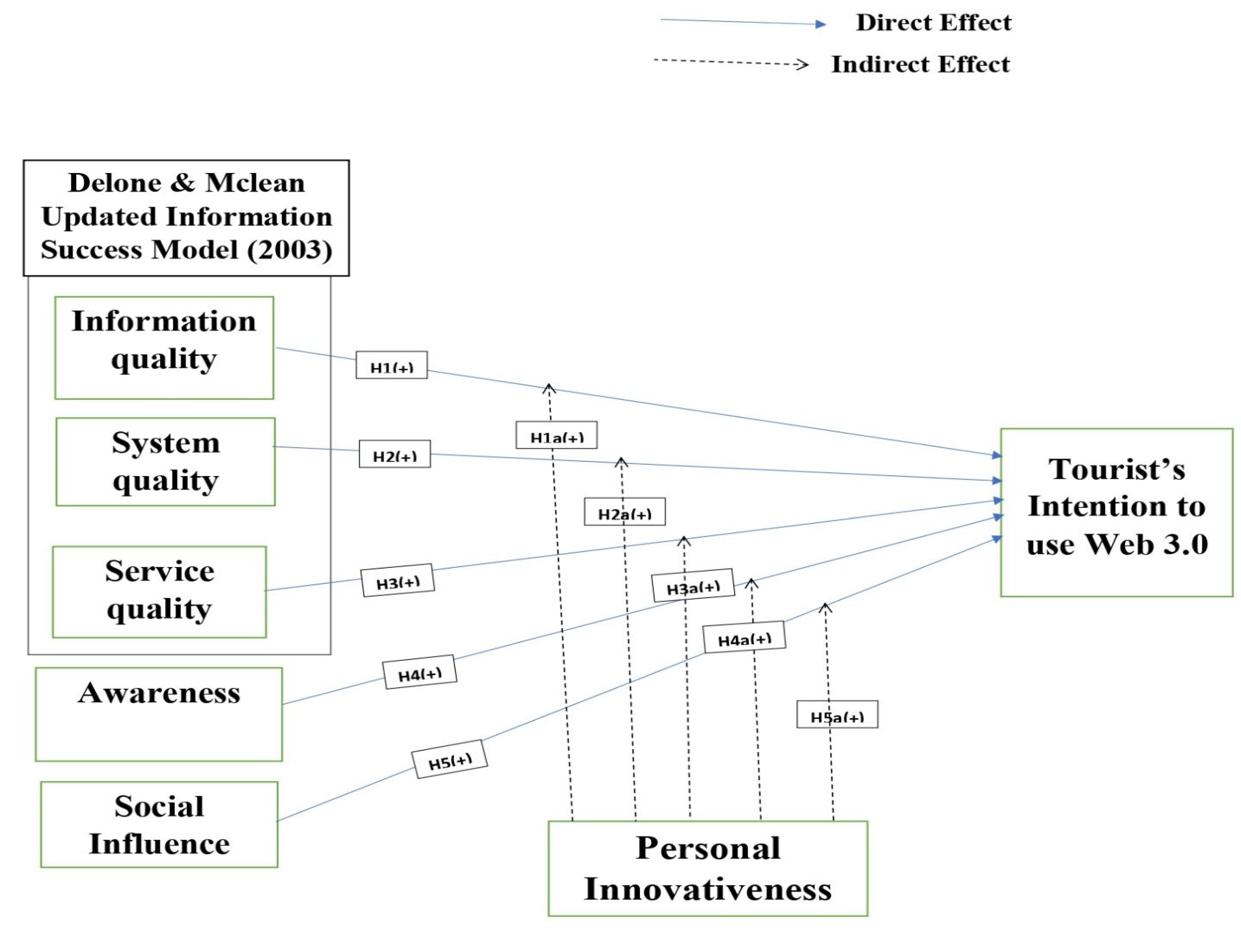

2.3. Development of Hypotheses

2.3.1. Information Quality and Tourists’ Intention

2.3.2. System Quality and Tourists’ Intention

2.3.3. Service Quality and Tourists’ Intention

2.3.4. Awareness and Tourists’ Intention

2.3.5. Social Influence and Tourists’ Intention

2.3.6. Personal Innovativeness and Tourists’ Intention

2.4. Research Framework

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Frequency Distribution of Respondents’ Profiles

4.2. Empirical Results

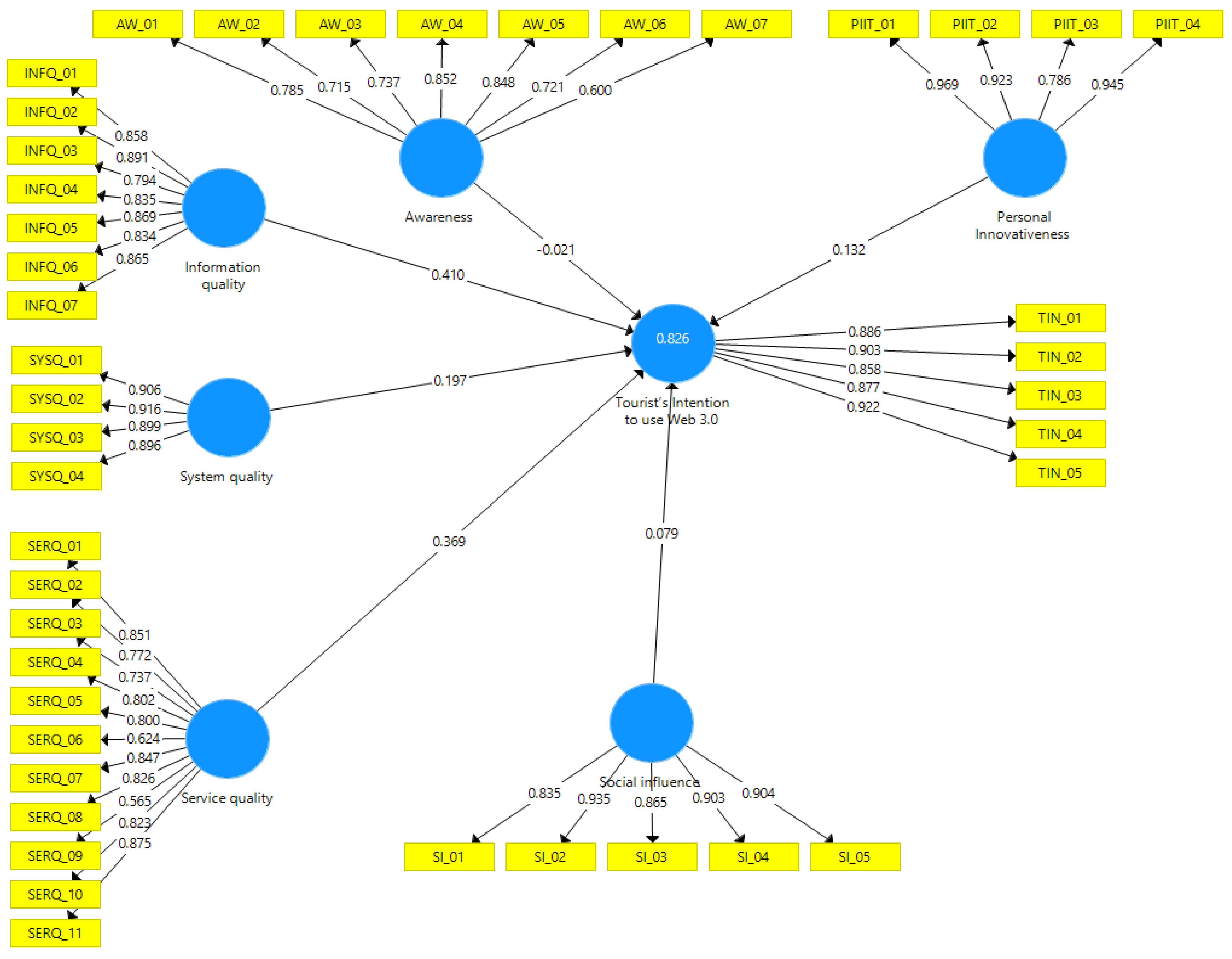

4.3. Item Reliability (Factor Loading Test)

4.4. Hypothesis Testing Using Path Coefficients

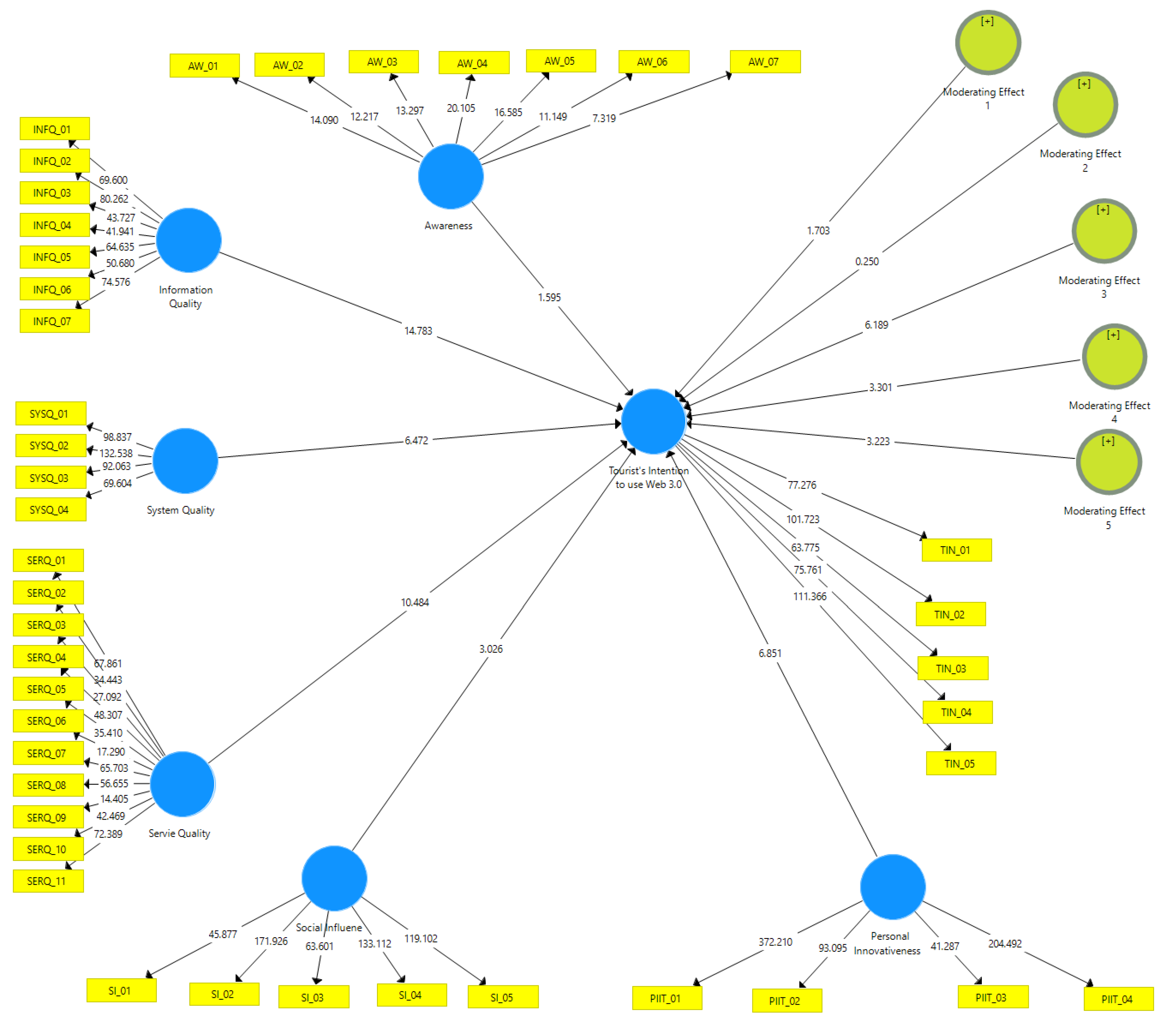

4.5. Moderating Path Coefficient Assessment

4.6. Predictive Ability of the Model (R-Squared)

4.7. Evaluation of Effect Size (f-Squared)

4.8. Assessment of Predictive Relevance of the Model (Q-Squared)

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Practice and Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| World Wide Web Platforms | Founder/Creator | Main Features | Application Examples | Advantages | Limitations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web 2.0 | Tim O’Reilly (2004) |

| YouTube Blogs MySpace Flickr Online games iTunes Forums Gmail Google Docs Google Earth Yahoo Skype Zoom Snapchat Google+ Line TripAdvisor (Facebook and Twitter email, instant messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp, Signal) Really Simple Syndication (RSS) news feeds Search engine optimization (SEO) Tagging (metadata used to describe Web content) BitTorrent Napster Wikis Tagging (folksonomy) |

|

| [116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124] |

| Web 3.0 | Tim Berners-Lee (still evolving and being defined) |

| SIOC Project Dbpedia Three-dimensional (3D street view, 3D games, metaverse, avatars, 3D graphics, augmented/virtual reality technologies, brave browser) Voice Assistants (Siri) Blockchain technology (smart contracts, cryptocurrency, Wolfram Alpha Interplanetary File System (IPFS)) |

|

|

| Construct | Code | Measurement Item | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Quality | SYSQ1 | “I believe Web 3.0 technology applications as an e-tourism tool to be easy to use”. | [29,36,125] |

| SYSQ2 | “I believe Web 3.0 technology applications as an e-tourism tool will allow information to be readily accessible to me”. | [29,36,126] | |

| SYSQ3 | “I believe Web 3.0 technology applications as an e-tourism tool will easily allow me to find the information I’m looking for”. | [29,36,127] | |

| SYSQ4 | “I believe Web 3.0 technologies applications as an e-tourism tool to be more well-structured”. | [29,36,127] | |

| Information Quality | INFQ1 | “Using Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool provides up-to-date information about tourism”. | [29,36,128] |

| INFQ2 | “Using Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool provides accurate information about tourism”. | [29,36,129] | |

| INFQ3 | “Using Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool provides relevant information”. | [29,36,130] | |

| INFQ4 | “Using Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool provides comprehensive and complete set of information”. | [29,36,130,131] | |

| INFQ5 | “Using Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool provides organized and classified information”. | [29,36,130] | |

| INFQ6 | “The information provided by Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool is understandable”. | [29,36,127] | |

| INFQ7 | “The information provided by Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool is reliable”. | [29,36,127] | |

| INFQ8 | “The information provided by Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool is useful”. | [29,36,127] | |

| Service Quality | SERQ1 | “Web 3.0 technology as an e-tourism tool provide quick responses to my requests”. | [29,36,132] |

| SERQ2 | “I could use Web 3.0 technology services as an e-tourism tool at anytime, anywhere I want”. | [29,36,129] | |

| SERQ3 | “Web 3.0 technology as an e-tourism tool allow tourists control over their tourism activity”. | [29,36,133] | |

| SERQ4 | “Web 3.0 technology as an e-tourism tool can present tourism activities more organized and accurate”. | [29,36,133] | |

| SERQ5 | “Web 3.0 technology as an e-tourism tool enables interactive communication between tourism agents and tourists”. | [29,36,133] | |

| SERQ6 | “Web 3.0 technology as an e-tourism tool makes it easy for me to share my trips with my friends”. | [29,36,128] | |

| SERQ7 | “I feel safe when I use tourism sites supported with Web 3.0 technology applications”. | [29,36,134] | |

| SERQ8 | “Tourism sites using Web 3.0 technology applications are secure”. | [29,36,130] | |

| SERQ9 | “Tourism sites using Web 3.0 technology applications are reliable”. | [29,36,130] | |

| SERQ10 | “When I use a search engine to seek information about specific tourism destinations, Web 3.0 technology provides the right solution to my request”. | [29,36,135] | |

| SERQ11 | “In general, the response time of Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool is consistent”. | [29,36,136] | |

| User Awareness | AW1 | “I am aware that Web 3.0 technology as an e-tourism tool will provide support for online intelligent search in the tourism domain”. | [96,137,138] |

| AW2 | “I am aware that Web 3.0 will help me to choose tourism destinations that I want to visit”. | [96,137] | |

| AW3 | “I receive enough information about the benefits of Web 3.0 in the tourism domain”. | [96,137] | |

| AW4 | “I am aware of the importance of Web 3.0 and its applications in the tourism domain”. | [96,137] | |

| AW5 | “I am aware that Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool will help to ease my travel-related arrangements”. | [96,137] | |

| AW6 | “I’m aware that Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool will enhance my tourism travel experience”. | [96,137,139] | |

| AW7 | “I believe that Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool will give me the opportunity to have sufficient information about tourism”. | [96,137,139] | |

| Social Influence | SI1 | “People who influence my behavior think that I should use Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool”. | [57,136,140] |

| SI2 | “People who are important to me think that I should use Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool”. | [57,140,141] | |

| SI3 | “People whose opinions I value prefer that I use Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool”. | [57,140,141] | |

| SI4 | “I believe that some of my colleagues use Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool for their personal travel”. | [57,140,141,142] | |

| SI5 | “I believe that my colleagues expect me to use Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool for my personal travel”. | [57,140,141,142] | |

| Personal Innovativeness | PI1T | “Generally, I spend a lot of time exploring how to use new online services”. | [143,144] |

| PIT2 | “Among my peers, I am usually the first to try out new online services”. | [143,144] | |

| PIT3 | “If I heard about a new information technology, I would look for ways to experiment with it”. | [143,144] | |

| PIT4 | “I like to experiment with new information technologies”. | [143,144] | |

| Intention | INT 1 | “I will intend to use Web 3.0 for tourism purpose whenever the service is available”. | [145,146,147,148,149,150] |

| INT 2 | “Whenever possible, I intend to use Web 3.0 applications to find any information relevant to tourism”. | [145,146,147,148,149,150] | |

| INT 3 | “I absolutely intend to search online for tourism related products and services through search engines that adopt Web 3.0 as an e-tourism tool”. | [145,146,147,148,149,150] | |

| INT 4 | “I predict that I will use Web 3.0 applications in the next year”. | [145,146,147,148,149,150] | |

| INT 5 | “I intend to use Web 3.0 services when they are widely launched”. | [145,146,147,148,149,150] |

References

- Habibi, F. The determinants of inbound tourism to Malaysia: A panel data analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, N.W.; You, J.-J.; Ruangkanjanases, A.; Chen, S.-C.; Pan, C.-I. Assessing the effects of information system quality and relationship quality on continuance intention in e-tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pencarelli, T. The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laddha, S.S.; Jawandhiya, P.M. Onto-Semantic Indian Tourism Information Retrieval System. In Recent Studies on Computational Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Laddha, S.; Jawandhiya, P.M. Novel concept of spelling correction for semantic tourism search interface. In Information and Communication Technology for Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. Internet tourism resource retrieval using PageRank search ranking algorithm. Complexity 2021, 2021, 5114802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamine, L.; Daoud, M. Evaluation in contextual information retrieval: Foundations and recent advances within the challenges of context dynamicity and data privacy. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, J.; Song, W. Short-term forecasting of Japanese tourist inflow to South Korea using Google trends data. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaom, M.A.; Sidi, F.; Jabar, M.A.; Abdullah, R.; Ishak, I.; Yunikawati, N.; Al-Harasi, A. The impact of tourist’s intention to use web 3.0: A conceptual integrated model based on TAM & DMISM. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2021, 99, 6222–6238. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, T.L. Trend Analysis of Technologies Supporting the Availability of Online Content: From Keyword-Based Search to the Semantic Web. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Commun. 2020, 7, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandoli, L.; Quinto, I.; De Liddo, A.; Buckingham Shum, S. On online collaboration and construction of shared knowledge: Assessing mediation capability in computer supported argument visualization tools. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.S. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, M.; Hashim, H. Integrating web 2.0 technology in ESL classroom: A review on the benefits and barriers. J. Couns. Educ. Technol. 2019, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivarajah, U.; Weerakkody, V.; Irani, Z. Opportunities and challenges of using web 2. 0 technologies in government. In Proceedings of Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society, Swansea, UK, 13–15 September 2016; pp. 594–606. [Google Scholar]

- Badiger, K.G.; Prabhu, S.M.; Badiger, M. Application of Web 2.0 and Web 3.0: An Overview. Int. J. Inf. Mov. 2018, 2, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, D. Application of Web 2.0 and Web 3.0: An Overview; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, K.; Dhar, S.; Basishtha, S. Web 1.0 to Web 3.0-Evolution of the Web and its various challenges. In Proceedings of 2014 International Conference on Reliability Optimization and Information Technology (ICROIT), Faridabad, India, 6–8 February 2014; pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M. Web 2.0 and destination marketing: Current trends and future directions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokbulut, B. The effect of Mentimeter and Kahoot applications on university students’ e-learning. World J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 12, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S. Effects of personal innovativeness on mobile device adoption by older adults in South Korea: The moderation effect of mobile device use experience. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2019, 17, 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, R.; Bruwer, R. Defining Web 3.0: Opportunities and challenges. Electron. Libr. 2016, 34, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, N.T.; Mondal, S.R.; Van, N.T.T.; Dzung, P.T.; Minh, D.X.H.; Das, S. A study on the role of web 4.0 and 5.0 in the sustainable tourism ecosystem of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulić Ceballos, J. The impact of Web 3.0 technologies on tourism information systems. In Sinteza 2014—Impact of the Internet on Business Activities in Serbia and Worldwide; Singidunum University: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014; pp. 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mili, H.; Valtchev, P.; Szathmary, L.; Boubaker, A.; Leshob, A.; Charif, Y.; Martin, L. Ontology-based model-driven development of a destination management portal: Experience and lessons learned. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2018, 48, 1438–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.J.; Camarinha, A.P.; Abreu, A.J.; Teixeira, S.F.; da Silva, A.F. An analysis of the most used websites in Portugal regarding accessibility web in the tourism sector. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Tour. 2021, 5, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Casillo, M.; Clarizia, F.; Colace, F.; Lombardi, M.; Pascale, F.; Santaniello, D. An approach for recommending contextualized services in e-tourism. Information 2019, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, R.A.; Albahri, A.S.; Alwan, J.K.; Al-Qaysi, Z.; Albahri, O.S.; Zaidan, A.; Alnoor, A.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Zaidan, B. How smart is e-tourism? A systematic review of smart tourism recommendation system applying data management. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 39, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angele, K.; Fensel, D.; Huaman, E.; Kärle, E.; Panasiuk, O.; Şimşek, U.; Toma, I.; Wahler, A. Semantic Web empowered E-tourism. In Handbook of e-Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, C.-K. Virtual travel experience and destination marketing: Effects of sense and information quality on flow and visit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Lee, K.Y.; Shin, S.I.; Yang, S.B. Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of Sina Weibo. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, S.; DeLone, W.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the independent variables. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 29, 7–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.J.; Koo, C. The influence of tourism website on tourists’ behavior to determine destination selection: A case study of creative economy in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 96, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Tsai, J.-L. Determinants of behavioral intention to use the Personalized Location-based Mobile Tourism Application: An empirical study by integrating TAM with ISSM. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 96, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Chung, N.; Ahn, K.M. The impact of mobile tour information services on destination travel intention. Inf. Dev. 2019, 35, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldholay, A.; Isaac, O.; Abdullah, Z.; Abdulsalam, R.; Al-Shibami, A.H. An extension of Delone and McLean IS success model with self-efficacy: Online learning usage in Yemen. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2018, 35, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.H.; Ye, H.; Law, R. Systematic review of smart tourism research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, N.; Shariff, A.; Manap, N.R.A. Determinants of awareness on Islamic financial institution e-banking among Malaysian SMEs. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Varajão, J.; Trigo, A. ISRI-Information Systems Research Constructs and Indicators: A Web Tool for Information Systems Researchers. J. Inf. Sci. Theory Pract. 2021, 9, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, G.; Adam, S.; Denize, S.; Kotler, P. Principles of Marketing; Pearson Australia: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M.; Kim, J.-I. Diffusion of innovations in public organizations. Innov. Public Sect. 1985, 1, 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sabeh, H.N.; Husin, M.H.; Kee, D.M.H.; Baharudin, A.S.; Abdullah, R. A Systematic Review of the DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success in an E-Learning Context (2010–2020). IEEE Access 2021, 9, 81210–81235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book, L.A.; Tanford, S. Measuring social influence from online traveler reviews. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2019, 3, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simarmata, M.T.; Hia, I.J. The role of personal innovativeness on behavioral intention of Information Technology. J. Econ. Bus. 2020, 1, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Pandey, A. Examining moderating role of personal identifying information in travel related decisions. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šorgo, A.; Ploj Virtič, M.; Dolenc, K. Differences in personal innovativeness in the domain of information technology among university students and teachers. J. Inf. Organ. Sci. 2021, 45, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Hsieh, J.P.-A. The contingent effect of personal IT innovativeness and IT self-efficacy on innovative use of complex IT. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2013, 32, 1105–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Prasad, J. A conceptual and operational definition of personal innovativeness in the domain of information technology. Inf. Syst. Res. 1998, 9, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-J. Moderating effects of personal innovativeness in mobile banking service. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, D.; Midhunchakkaravarthy, D.; Isaac, O.; Ameen, A.; Duraisamy, B.; Janarthanan, M. The Moderation Impact of Personal Innovativeness on the Relationship Between E-Learning Strategy Implementation and High Education Organizational Performance. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 3249–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, A.; Arasli, H.; Ozturen, A.; Daskin, M. Feeling the service product closer: Triggering visit intention via virtual reality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A. New technologies used in COVID-19 for business survival: Insights from the Hotel Sector in China. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.; Elshaer, I.; Shaker, A. The successful adoption of is in the tourism public sector: The mediating effect of employees’ trust. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqableh, M.; Hmoud, H.Y.; Jaradat, M. Integrating an information systems success model with perceived privacy, perceived security, and trust: The moderating role of Facebook addiction. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-T.B.; Gebsombut, N. Communication factors affecting tourist adoption of social network sites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, O.; Aldholay, A.; Abdullah, Z.; Ramayah, T. Online learning usage within Yemeni higher education: The role of compatibility and task-technology fit as mediating variables in the IS success model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalasi, K.; Ameen, A.; Isaac, O.; Khalifa, G.S.; Midhunchakkaravarthy, D. Impact of actual usage of smart government on the net benefits (knowledge acquisition, communication quality, competence, productivity, decision quality). Test Eng. Manag. 2020, 82, 14770–14782. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 7th ed.; Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-119-26684-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund, W.G.; Babin, B.J.; Carr, J.C.; Griffin, M. Business Research Methods; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1111826925. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Kim, Y. Searching customer patterns of mobile service using clustering and quantitative association rule. Expert Syst. Appl. 2008, 34, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullateef, A.O.; Biodun, A.B. Are international students tourists? Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2014, 13, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, R.; Gatsinzi, J. Foreign students as tourists: Educational tourism, a market segment with potential. Afr. Insight 2005, 35, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Are Chinese international students in the UK tourists? In Asian Tourism: Growth and Change; Cochrane, J., Ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyer, K.; Ozgit, H.; Rjoub, H. Applying an Evolutionary Growth Theory for Sustainable Economic Development: The Effect of International Students as Tourists. Sustainability 2020, 12, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Buchanan, F.R.; Ahmad, N. Examination of students’ selection criteria for international education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, N. International Students as Tourists: Implications for Educators. In The Study of Food, Tourism, Hospitality and Events; Beeton, S., Morrison, A., Eds.; Tourism, Hospitality & Event Management; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, M.; Borzooei, M. Evaluating the learning outcomes of international students as educational tourists. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2013, 5, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Asgari, M.; Borzooei, M. Evaluating the perception of Iranian students as educational tourists toward Malaysia: In-depth interviews. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2014, 5, 81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo, M.I.C.; Zapatero, M.I.R.; Naranjo, L.M.P.; López-Guzmán, T. Motivations of educational tourists in non-English-speaking countries: The role of languages. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 35, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnaro, E.; Staffieri, S. A study of students’ travellers values and needs in order to establish futures patterns and insights. J. Tour. Futures 2015, 1, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.J.G.; Jiménez, J.M. The role of tourist destination in international students’ choice of academic center: The case of erasmus programme in the Canary Islands. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2015, 13, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Mapping Educational Tourists’ Experience in the UK: Understanding international students. Third World Q. 2008, 29, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, A.; Pearce, P. Multi-faceted image assessment: International students’ views of Australia as a tourist destination. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2005, 18, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrab, M. Factors Affecting Acceptance and The Use of Technology in Yemeni Telecom Companies. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-Y.; Jeon, Y.J.J. The difference of user satisfaction and net benefit of a mobile learning management system according to self-directed learning: An investigation of cyber university students in hospitality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, D.; Kazemi, F. Innovation diffusion theory and customers’ behavioral intention for Islamic credit card: Implications for awareness and satisfaction. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 11, 1245–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ziadat, M.T.; Al-Majali, M.M.; Al Muala, A.M.; Khawaldeh, K.H. Factors affecting university student’s attitudes toward E-commerce: Case of Mu’tah University. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2013, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alzubi, M.M.; Alkhawlani, M.A.; El-Ebiary, Y.A.B. Investigating the factors affecting University students’e-commerce intention towards: A case study of Jordanian universities. J. Bus. Retail Manag. Res. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Zin, M.L.M.; Majid, A.H.A. Impact of Intention and Technology Awareness on Transport Industry’s E-service: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. J. Ind. Distrib. Bus. 2016, 7, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hu, Q. The centrality of awareness in the formation of user behavioral intention toward protective information technologies. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2007, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top, E.; Yukselturk, E.; Cakir, R. Gender and Web 2.0 technology awareness among ICT teachers. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 42, E106–E109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungco, C.Y.; Madrigal, D.V. Awareness and Utilization of Web 2.0 Technology of Young Teachers in Catholic Schools. Philipp. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 3, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.T.; Kunasekaran, P.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; AriRagavan, N.; Thomas, T.K. Investigating the determinants and process of destination management system (DMS) implementation. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2021, 35, 308–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Chan-Olmsted, S.; Park, B.; Kim, Y. Factors affecting e-book reader awareness, interest, and intention to use. New Media Soc. 2012, 14, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassegger, T.; Nedbal, D. The role of employees’ information security awareness on the intention to resist social engineering. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Islam, M.; Khan, M.; Ramayah, T. The adoption of mobile commerce service among employed mobile phone users in Bangladesh: Self-efficacy as a moderator. Int. Bus. Res. 2011, 4, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Akther, T.; Nur, T. A model of factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: A synthesis of the theory of reasoned action, conspiracy theory belief, awareness, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurakhimovna, T.S.; Alzubi, M.M.S.; Aljounaidi, A. The effect of mediating role for awareness factors on the behavioral intention to use in E-commerce services in uzbekistan. Int. J. All Res. Writ. 2021, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhaldi, A.N. An empirical examination of customers’ mobile phone experience and awareness of mobile banking services in mobile banking in Saudi Arabia. J. Inform. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 12, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Velmurugan, M.S.; Velmurugan, M.S. Consumers’ awareness, perceived ease of use toward information technology adoption in 3G mobile phones’ usages in India. Asian J. Mark. 2014, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mutahar, A.M.; Daud, N.M.; Ramayah, T.; Isaac, O.; Aldholay, A.H. The effect of awareness and perceived risk on the technology acceptance model (TAM): Mobile banking in Yemen. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 2018, 12, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, S.A.; Kassim, S. Examining the relationship between UTAUT construct, technology awareness, financial cost and E-payment adoption among microfinance clients in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the 1st Aceh Global Conference (AGC 2018), Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 17–18 October 2018; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 292, pp. 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, F.M.; Ahmad, H.B. Mediating role of technology awareness on social influence–behavioural intention relationship. Infrastruct. Univ. Kuala Lumpur Res. 2014, 2, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Q. The influence of hotel price on perceived service quality and value in e-tourism: An empirical investigation based on online traveler reviews. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book, L.A.; Tanford, S.; Chen, Y.-S. Understanding the impact of negative and positive traveler reviews: Social influence and price anchoring effects. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book, L.A.; Tanford, S.; Montgomery, R.; Love, C. Online Traveler Reviews as Social Influence: Price Is No Longer King. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 42, 445–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.L.; Montgomery, R.J. The Effects of Social Influence and Cognitive Dissonance on Travel Purchase Decisions. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Gerritsen, R. What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 10, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Stock, D.; McCarthy, L. Customer Preferences for Online, Social Media, and Mobile Innovations in the Hospitality Industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2012, 53, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briciu, A.; Briciu, V.-A. Participatory culture and tourist experience: Promoting destinations through YouTube. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Tučková, Z.; Jibril, A.B. The role of social media on tourists’ behavior: An empirical analysis of millennials from the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedera, D.; Lokuge, S.; Atapattu, M.; Gretzel, U. Likes—The key to my happiness: The moderating effect of social influence on travel experience. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asvikaa, V.; Gupta, D. The Social Travelers: Factors Impacting Influence of Location Sharing in Social Media On Motivation To Travel. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Bangalore, India, 9–22 September 2018; pp. 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Nunkoo, R.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Indian Travellers’ Adoption of Airbnb Platform. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangmee, C.; Kot, S.; Meekaewkunchorn, N.; Kassakorn, N.; Khalid, B. Factors Determining the Behavioral Intention of Using Food Delivery Apps during COVID-19 Pandemics. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopdar, P.K.; Paul, J.; Prodanova, J. Mobile shoppers’ response to Covid-19 phobia, pessimism and smartphone addiction: Does social influence matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Budac, C.; Baltador, L.A.; Dabija, D.-C. Assessing the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on M-Commerce Adoption: An Adapted UTAUT2 Approach. Electronics 2022, 11, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y. An Empirical Study on the Influence of the Mobile Information System on Sports and Fitness on the Choice of Tourist Destinations. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 2021, 5303590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, H.; Tareq, M.A. Moderating effects of personal innovativeness and driving experience on factors influencing adoption of BEVs in Malaysia: An integrated SEM–BSEM approach. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, O.; Berezina, K.; Kang, M. Effect of Personal Innovativeness on Technology Adoption in Hospitality and Tourism: Meta-analysis. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Wörndl, W., Koo, C., Stienmetz, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, J.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. An overview of Web 2.0 social capital: A cross-cultural approach. Serv. Bus. 2014, 8, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.; Williams, M.; Mitra, A.; Niranjan, S.; Weerakkody, V. Understanding advances in web technologies: Evolution from web 2.0 to web 3.0. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2011 Proceedings, Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 June 2011; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/257 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Bruwer, H.J. An Investigation of Developments in Web 3.0: Opportunities, Risks, Safeguards and Governance; Stellenbosch University: Stellenbosch, South Sfrica, 2014; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/86535 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Saqib, N.A.; Salam, A.A.; Atta-Ur-Rahman; Dash, S. Reviewing risks and vulnerabilities in web 2.0 for matching security considerations in web 3.0. J. Discret. Math. Sci. Cryptogr. 2021, 24, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulpeter, D. The Genesis and Emergence of Web 3.0: A Study in the Integration of Artificial Intelligence and the Semantic Web in Knowledge Creation. Master’s Thesis, Technological University Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Salminen, A. Mashups in Web 3.0. In Proceedings of WEBIST, Porto, Portugal, 18–21 April 2012; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hendler, J.; Berners-Lee, T. From the Semantic Web to social machines: A research challenge for AI on the World Wide Web. Artif. Intell. 2010, 174, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, B.P.; Vinay, M.; Shalini, B.; JS, M.R. An integrative review of Web 3.0 in academic libraries. Libr. Hi Tech News 2018, 35, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, B.; Kenchakkanavar, A.Y. An alteration of the web 1.0, web 2.0 and web 3.0: A comparative study. Imp. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2016, 2, 705–710. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T. An empirical examination of initial trust in mobile banking. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Williams, M.D. Evaluating the validity of IS success models for the electronic government research: An empirical test and integrated model. Int. J. Electron. Gov. Res. (IJEGR) 2013, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, N.; Smolnik, S.; Riempp, G. An empirical investigation of employee portal success. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.S.; Wang, C.H. Antecedences to continued intentions of adopting e-learning system in blended learning instruction: A contingency framework based on models of information system success and task-technology fit. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Fofanah, S.S.; Liang, D. Assessing citizen adoption of e-Government initiatives in Gambia: A validation of the technology acceptance model in information systems success. Gov. Inf. Q. 2011, 28, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H. Investigating users’ perspectives on e-learning: An integration of TAM and IS success model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chengalur-Smith, I. Factors influencing students’ use of a library Web portal: Applying course-integrated information literacy instruction as an intervention. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 26, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Chiu, C.S.; Chang, H.C. Examining the integrated influence of fairness and quality on learners satisfaction and Web-based learning continuance intention. Inf. Syst. J. 2007, 17, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pituch, K.A.; Lee, Y.-K. The influence of system characteristics on e-learning use. Comput. Educ. 2006, 47, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Liu, G.; Qian, C.; Song, Y.F. Customer acceptance of internet banking: Integrating trust and quality with UTAUT model. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Service Operations and Logistics, and Informatics, Beijing, China, 12–15 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, J.C.; Chiu, C.-M.; Martínez, F.J. Understanding e-learning continuance intention: An extension of the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-M. Antecedents and consequences of e-learning acceptance. Inf. Syst. J. 2010, 21, 269–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Somali, S.A.; Gholami, R.; Clegg, B. An investigation into the acceptance of online banking in Saudi Arabia. Technovation 2009, 29, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.; Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.; Hu, P.; Tam, K.; Thong, J.; Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. University of Arkansas; University of Arizona; University of Utah. Modeling Citizen Satisfaction with Mandatory Adoption of an E-Government Technology. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochukwu, I.U.; Hocanin, F.T. Awareness of students on the usefulness of ICT tools in education: Case of EMU. IOSR J. Res. Method Educ. 2017, 7, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; Dennis, A.R.; Venkatesh, V. Predicting collaboration technology use: Integrating technology adoption and collaboration research. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 9–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkiewicz, H.R.; Regstad, N.G. Using Subjective Norms to Predict Teachers’ Computer Use. J. Comput. Teach. Educ. 1996, 13, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-M. Exploring the intention to use mobile learning: The moderating role of personal innovativeness. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2014, 16, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkawsi, G.; Ali, N.; Baashar, Y. The Moderating Role of Personal Innovativeness and Users Experience in Accepting the Smart Meter Technology. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-W.; Kim, Y.-G. Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web context. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaruwachirathanakul, B.; Fink, D. Internet banking adoption strategies for a developing country: The case of Thailand. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkarainen, T.; Pikkarainen, K.; Karjaluoto, H.; Pahnila, S. Consumer acceptance of online banking: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Teo, T.S. Factors influencing the adoption of Internet banking. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathye, S.; Prasad, B.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, P.; Sathye, M. Factors influencing the intention to use of mobile value-added services by women-owned microenterprises in Fiji. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2018, 84, e12016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Purpose | Theory/Model/Framework | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | “to examine essential characteristics of virtual reality (VR) that influence individual visit intention toward touristic products”. | DMISM | “VR, as a marketing medium, creates positive impacts and stimulates individuals’ intention to visit destinations”. |

| [52] | “to determine innovative technologies being deployed to lessen pandemic’s impact on hotel industry in China”. | DMISM | “Live-stream promotion and conferences can enhance information quality, while 5G technology and Wi-Fi 6 can enhance system quality, with innovative technological tools such as robots, artificial intelligence, and facial recognition used to help provide better service”. |

| [53] | “to examine mediating role of management-, provider-, and system-based trust in relationship between tourism IS system, information, and service quality with employee satisfaction and intention to use and actually use system”. | DMISM | “trust directly affects intention to use, actual use, and user satisfaction, and completely mediates the effect of IS qualities on these factors”. |

| [54] | “to investigate influence of perceived security, perceived privacy, and satisfaction on users’ intention to continue using Facebook”. | DMISM | “perceived privacy and satisfaction have significant impacts on Facebook continuance intention”. |

| [2] | “to propose a model for formation of relationship quality (customer satisfaction and trust), information system quality, perceived value, and customers’ intention to continue in e-tourism environment”. | DMISM | “customer satisfaction has a positive effect on continuance intention, and information system quality has a positive relationship with customer satisfaction, trust, and customer continuance intention”. |

| [55] | “to explore how communication elements of social networking sites (SNSs), as part of STTs, enhance tourists’ motivation and usage intention”. | DMISM | “Internet self-efficacy, information quality, and systems quality trigger information-seeking motivation while service quality and source credibility positively determine relationship maintenance motivation”. |

| Demographic Categories | Frequency (n = 643) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 165 | 26% |

| Male | 478 | 74% |

| Age | ||

| 20–24 years | 385 | 60% |

| 25–29 years | 194 | 30% |

| 30–40 years | 61 | 10% |

| 41–50 years | 3 | 1% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 568 | 88% |

| Married | 75 | 12% |

| Education Level | ||

| Bachelor | 475 | 74% |

| Master | 100 | 16% |

| PhD | 68 | 11% |

| University Name | ||

| University of Malaya (UM) | 46 | 7% |

| University Putra Malaysia (UPM) | 232 | 36% |

| University Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) | 35 | 5% |

| International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) | 35 | 5% |

| Limkokwing University (LUCT) | 139 | 22% |

| SEGi University, Malaysia (SEGi) | 89 | 14% |

| Asia Pacific University of Technology & Innovation (APU) | 49 | 8% |

| Taylor’s University | 18 | 3% |

| Times Traveling Using Internet | ||

| 1–2 times | 322 | 50% |

| 3–4 times | 246 | 38% |

| 4–5 times | 59 | 9% |

| More than 5 times | 16 | 3% |

| Variable Name | Item Label | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Information Quality | INFQ_01 | 0.858 |

| INFQ_02 | 0.891 | |

| INFQ_03 | 0.794 | |

| INFQ_04 | 0.835 | |

| INFQ_05 | 0.869 | |

| INFQ_06 | 0.834 | |

| INFQ_07 | 0.865 | |

| INFQ_08 | Item deleted due to low loading | |

| System Quality | SYSQ_01 | 0.906 |

| SYSQ_02 | 0.916 | |

| SYSQ_03 | 0.899 | |

| SYSQ_04 | 0.896 | |

| Service Quality | SERQ_01 | 0.851 |

| SERQ_02 | 0.772 | |

| SERQ_03 | 0.737 | |

| SERQ_04 | 0.802 | |

| SERQ_05 | 0.800 | |

| SERQ_06 | 0.624 | |

| SERQ_07 | 0.847 | |

| SERQ_08 | 0.826 | |

| SERQ_09 | 0.565 | |

| SERQ_10 | 0.823 | |

| SERQ_11 | 0.875 | |

| User Awareness | AW_01 | 0.785 |

| AW_02 | 0.716 | |

| AW_03 | 0.737 | |

| AW_04 | 0.852 | |

| AW_05 | 0.848 | |

| AW_06 | 0.721 | |

| AW_07 | 0.600 | |

| Social Influence | SI_01 | 0.835 |

| SI_02 | 0.935 | |

| SI_03 | 0.865 | |

| SI_04 | 0.903 | |

| SI_05 | 0.904 | |

| Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | TIN_01 | 0.886 |

| TIN_02 | 0.902 | |

| TIN_03 | 0.856 | |

| TIN_04 | 0.878 | |

| TIN_05 | 0.922 | |

| Personal Innovativeness | PIIT_01 | 0.969 |

| PIIT_02 | 0.923 | |

| PIIT_03 | 0.786 | |

| PIIT_04 | 0.945 |

| Variable | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Quality | 0.936 | 0.938 | 0.948 | 0.722 |

| System Quality | 0.926 | 0.940 | 0.947 | 0.818 |

| Service Quality | 0.934 | 0.942 | 0.944 | 0.609 |

| User Awareness | 0.876 | 0.915 | 0.902 | 0.571 |

| Social Influence | 0.934 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.791 |

| Personal Innovativeness | 0.928 | 0.948 | 0.950 | 0.825 |

| Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.934 | 0.936 | 0.950 | 0.791 |

| INFQ | SYSQ | SERQ | AW | SI | TIN | PIIT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INFQ | 0.850 | ||||||

| SYSQ | 0.626 | 0.904 | |||||

| SERQ | 0.761 | 0.652 | 0.780 | ||||

| AW | −0.157 | −0.080 | −0.098 | 0.756 | |||

| SI | −0.741 | −0.511 | −0.707 | 0.174 | 0.889 | ||

| TIN | 0.828 | 0.742 | 0.827 | −0.138 | −0.659 | 0.889 | |

| PIIT | 0.524 | 0.654 | 0.537 | −0.109 | −0.526 | 0.635 | 0.909 |

| H | Relationship | Std Beta | Std Error | t-Value | p-Value | Result | CI LL | CI UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Information Quality →. Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.271 | 0.030 | 9.075 | <0.001 | Supported | 0.211 | 0.328 |

| H2 | System Quality →. Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.141 | 0.029 | 4.812 | <0.001 | Supported | 0.084 | 0.198 |

| H3 | Service Quality →. Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.215 | 0.031 | 6.838 | <0.001 | Supported | 0.154 | 0.277 |

| H4 | User Awareness →. Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.319 | 0.750 | Unsupported | −0.027 | 0.033 |

| H5 | Social Influence →. Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.092 | 0.031 | 2.916 | 0.004 | Supported | 0.032 | 0.155 |

| H | Relationship | Std Beta | Std Error | t-Value | p-Value | Result | CI LL | CI UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6a | Moderating Effect 3 →. 10: Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.172 | 0.033 | 5.252 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.109 | 0.238 |

| H6b | Moderating Effect 4 →. 10: Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | 0.080 | 0.026 | 3.094 | 0.002 | Supported | 0.028 | 0.130 |

| H6c | Moderating Effect 5 →. 10: Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | −0.104 | 0.035 | 2.956 | 0.003 | Supported | −0.172 | −0.034 |

| H6d | Moderating Effect 7 →. 10: Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | −0.003 | 0.016 | 0.217 | 0.829 | Unsupported | −0.035 | 0.027 |

| H6e | Moderating Effect 8 →. 10: Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | −0.052 | 0.023 | 2.289 | 0.022 | Supported | −0.096 | −0.007 |

| Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 | |

|---|---|

| Information Quality | 0.140 |

| System Quality | 0.048 |

| Service Quality | 0.088 |

| User Awareness | 0.000 |

| Social Influence | 0.023 |

| Personal Innovativeness | 0.037 |

| H1: There is a significant effect of information quality on tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

| H2: There is a significant effect of system quality on tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

| H3: There is a significant effect of service quality on tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

| H4: There is a significant effect of user awareness on tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Not Supported |

| H5: There is a significant effect of social influence on tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

| H6a: Personal innovativeness moderates the relationship between information quality and tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

| H6b: Personal innovativeness moderates the relationship between system quality and tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

| H6c: Personal innovativeness moderates the relationship between service quality and tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

| H6d: Personal innovativeness moderates the relationship between user awareness and tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Not Supported |

| H6e: Personal innovativeness moderates the relationship between social influence and tourists’ intention to use Web 3.0 in Malaysia. | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albaom, M.A.; Sidi, F.; Jabar, M.A.; Abdullah, R.; Ishak, I.; Yunikawati, N.A.; Priambodo, M.P.; Nusari, M.S.; Ali, D.A. The Moderating Role of Personal Innovativeness in Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 Based on Updated Information Systems Success Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113935

Albaom MA, Sidi F, Jabar MA, Abdullah R, Ishak I, Yunikawati NA, Priambodo MP, Nusari MS, Ali DA. The Moderating Role of Personal Innovativeness in Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 Based on Updated Information Systems Success Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):13935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113935

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbaom, Mohammed Abdo, Fatimah Sidi, Marzanah A. Jabar, Rusli Abdullah, Iskandar Ishak, Nur Anita Yunikawati, Magistyo Purboyo Priambodo, Mohammed Saleh Nusari, and Dhakir Abbas Ali. 2022. "The Moderating Role of Personal Innovativeness in Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 Based on Updated Information Systems Success Model" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 13935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113935

APA StyleAlbaom, M. A., Sidi, F., Jabar, M. A., Abdullah, R., Ishak, I., Yunikawati, N. A., Priambodo, M. P., Nusari, M. S., & Ali, D. A. (2022). The Moderating Role of Personal Innovativeness in Tourists’ Intention to Use Web 3.0 Based on Updated Information Systems Success Model. Sustainability, 14(21), 13935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113935