Abstract

The luxury hotel market has been developing rapidly recently in the Asian Market. To provide useful outcomes to hotels competing in fierce market conditions, the current study investigated the relationship between customer experience values, customer post-experience consequences, and citizenship behaviors. Our findings confirmed the valuable contribution of customer experience values (ROI and service excellence) to the development of brand satisfaction, which in turn positively influences brand commitment and love. Meanwhile, brand commitment and love were found to have a direct positive impact on customer citizenship behaviors (CCBs). Overall, the findings bridge the gap in the relationship between brand love and CCBs in the hospitality industry and provide broad insights into brand management and marketing theories for tourism and hospitality.

1. Introduction

The growth rate of the luxury hotel market is expected to reach approximately 5% during 2018–2023. As the experience economy is becoming an industry-wide core component, luxury hotels as a part of the experience economy attempt to provide customers with a superior geographical location, 24-hour room service, an expansive space, expensive facilities, high-quality food, elegant aesthetics, privacy, security, and highly customized services [1,2]. With the popularity of luxury hotels in the hotel industry, exquisite decoration and upscale facilities have become the standard in every luxury hotel; therefore, customers have begun to pay attention to details and demand higher service and support facilities [3]. Thus, marketers and general managers of luxury hotels must attach great importance to the customer evaluations of service experiences provided by hotels and the subsequent behaviors via customers’ perceptions of service experiential value regarding their stay in a luxury hotel.

Owing to fierce competition among luxury hotels, the value of customers’ experiential value perception was re-examined as an important component in creating customer engagement in the hotel industry [4]. A personalized hotel experience would increase customers’ willingness to pay for a luxury hotel by 14%; more importantly, hotels providing excellent service during a stay would have 5.7 times more revenue than their competitors [5]. Consequently, Mathwick et al. [6] and other scholars have investigated the four dimensions of customer experiential value—that is, aesthetic value, playfulness, return on investment (ROI), and service excellence—to fully understand the experiences of hotel guests in the service industry. In line with these conceptual developments, a few scholars have attempted to investigate the concept of experiential value and its connection to co-creation behaviors [7], customer engagement [4], and food image in branding food tourism [8]. However, in the context of luxury hotels, it is necessary to investigate not only cognitive components (i.e., brand commitment) but also emotional and hedonic connections between guests and the hotel (i.e., brand love), while understanding guests’ subsequent behaviors after staying at a hotel.

To fill this gap in the literature, the current study includes brand satisfaction, commitment, and love as the immediate outcomes of customers’ experiential values and customer citizenship behaviors (CCBs) as the ultimate outcome. Recently, CCBs have been applied to studies in the tourism and hospitality industry to understand customers’ extra-role behaviors in response to their high levels of satisfaction, engagement, and loyalty [9]. Indeed, Cavalho and Alves [10] did a systematic literature review on customer value co-creation in the hospitality and tourism industry and found that CCBs are one of the outcomes of customer value co-creation behaviors. CCBs do not merely go beyond customers’ behaviors but encompass their positive, voluntary, helpful, and constructive behaviors [11]. The development of CCBs can help brands manage customer–brand relationships and improve customer influence, loyalty, and brand equity [12], as well as the performance of enterprises and their employees [13]. Thus, the present study deems that encouraging CCBs is especially conducive for luxury hotel brands to stand out amid fierce competition and maintain healthy development. Nevertheless, CCBs as an ultimate outcome have rarely been investigated in the context of luxury hotels, and the lack of research on CCBs has sparked heated debate among practitioners [14]. This study thus aims to enrich the theoretical understanding of the relationship between hotels and consumers. We hope that it will help luxury hotel managers better understand customers and provide practical and managerial suggestions from the research framework.

This study is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews previous literature including customer experiential value, customer post-experience evaluation (i.e., brand satisfaction, brand commitment, and brand love), and customer citizenship behavior (i.e., helping, advocacy, tolerance, and feedback); Section 3 describes the research design, data collection, and data analysis; Section 4 presents the findings of the current study via empirical analyses; and finally Section 5 concludes the current study by presenting theoretical and managerial implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Customer Experiential Value

In the era of the experience economy, products and services have become increasingly commoditized, and consequently, companies focus on ways to win severe competition [15,16]. Among many possible solutions, such as higher product quality, better physical atmosphere, and high-quality services, creating a better consumer experience has attracted great attention from practitioners and academics [17]. Some researchers, including Pine, Pine, and Gilmore [15], have emphasized the way of providing unique and high-service experiences, by not just simply providing commodities, products, or services themselves, but rather completing with unique experiences tailored to the products and services.

In line with the concept of the experience economy, experiential value is of significant interest from the consumer service experience perspective. Consumers generally perceive a certain level of experiential value when interacting with, experiencing, or receiving a particular service from service providers [18]. Bitner, et al. [19] asserted that special treatment or attention during service contact leads to higher satisfaction with service experience and, in turn, creates higher experiential value. Similarly, in the luxury hotel sector, a more customized or personalized service experience and a better physical atmosphere or environment, as compared to competitors, would escalate customers’ post-experience evaluation and, therefore, create a stronger experiential value.

Experiential value has been well documented in consumer literature [18]. Based on earlier studies [7,8,20], this study adopted a multidimensional approach to understand the determinants affecting post-experience behaviors, while considering the complexity and experiential characteristics of the hospitality industry. Thus, this study is primarily based on the conceptualization of Mathwick, Malhotra, and Rigdon [6] and applies the four aspects of experiential value, namely, aesthetic value, playfulness, ROI, and service excellence, in a luxury hotel setting. As customers’ perception of experiential value comes from the direct and distanced interaction with service providers [6], the experiential value of a luxury hotel experience could also be related to the entire journey of guest experience at the luxury hotel. Thus, the four dimensions adopted from Mathwick, Malhotra, and Rigdon [6] would be beneficial in fully understanding the whole picture of guests’ perceptions of exertional value in the luxury hotel context.

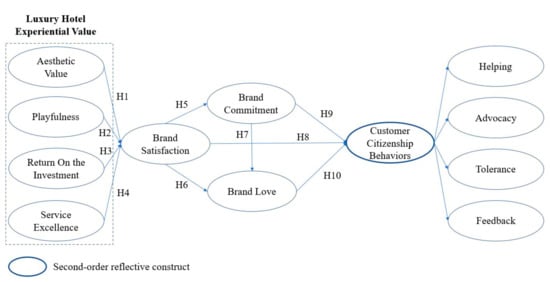

Aesthetic value is described as one’s subjective enjoyment derived from products or services, without considering their utility (Holbrook, 1980), and is therefore linked to personal feelings and emotions [21]. From the conceptualization by Mathwick, Malhotra, and Rigdon [6], aesthetic value comes from one’s primary senses, such as sight, hearing, taste, and touch. To comply with this conceptualization, Ahn, Lee, Back and Schmitt [7] highlighted that physical objects, visual appeal, and entertainment-related items could play an important role in creating aesthetic value through the good evaluation of service experience in the integrated resort setting. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypotheses Model.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The aesthetic value of the luxury hotel experience is positively correlated with brand satisfaction.

The concept of playfulness could be similar to the hedonic value of services, which potentially increases intrinsic motivation for specific leisure or tourism behaviors. In the context of experiential value, playfulness emphasizes consumers’ experience of playful, enjoyable, and interesting leisure consumption activities [22], reflecting the intrinsic pleasure of interesting activities, thus providing a way to escape the pressures of daily life [23]. In a luxury hotel environment, engaging or participating in diverse entertainment activities can create a high level of playfulness value, such as pleasure, fun, and enjoyment. Thus, this study hypothesized that perceived playfulness is a significant element in fostering favorable post-experience outcomes, such as brand satisfaction:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The playfulness of the luxury hotel experience is positively correlated with brand satisfaction.

In contrast to the hedonic aspect of service experience, customers’ perceived value of ROI is linked to the utilitarian aspect of service experience, such as their positive investment in financial, time, behavioral, and psychological resources for potential returns [6,24]. Thus, many customers expect their investment to be of high practical value and determine the impact of price equity on customer trust and satisfaction [25]. As luxury hotels are normally high-priced service products, it is easy to anticipate the important role of customers’ perceived value of ROI in causing customers’ post-experience behaviors. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The return on investment in luxury hotel experiences is positively correlated with brand satisfaction.

Service excellence reflects the superiority of the hospitality and tourism reception service performance in meeting customer expectations [6,7], articulated that service excellence comes from a combination of extrinsic and reactive values. Thus, this study argues that customers’ evaluation of service quality at a luxury hotel is influenced by the professional capabilities of the service staff, the reliability of overall service quality, and service performance.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The service excellence of the luxury hotel experience is positively correlated with brand satisfaction.

2.2. Customer Post-Experience Evaluations

Post-experience evaluations and consequences are reinforced when customer experiential value reaches a certain level [26]. Furthermore, customers’ positive experiential value often leads to positive evaluations and consequences (e.g., brand satisfaction). In turn, brand satisfaction influences brand evaluation processes (e.g., brand commitment and love) and customers’ subsequent behaviors [27]. Thus, this study argues that customers’ higher experiential value leads to better customer post-experience evaluations (e.g., brand satisfaction, commitment, and love).

2.2.1. Brand Satisfaction

Brand satisfaction refers to the cumulative satisfaction of consumers based on their purchase and experience of branded products or services [28]. This definition implies that brand satisfaction is the process of evaluating perceived differences between past expectations and actual consumption experiences. In a study on the hospitality sector, Gibson [29] discovered that satisfied customers become repeat customers of products or services and offer favorable feedback to family and friends about their experiences. Furthermore, positive feedback also leads to a high level of brand satisfaction, and consumers are more inclined to commit to the brand. Simultaneously, brand satisfaction is an important positive evaluation and consequence of the customer experience. When the degree of satisfaction reaches a certain level, it affects customers’ brand love. Undoubtedly, post-experience evaluations and consequences interact more strongly in the context of luxury hotels.

2.2.2. Brand Commitment

Fournier [30] asserted that a series of satisfying service experiences build a positive emotional connection between consumers and the brands they consume. In these connections, brand commitment acts as a response to the goal of preserving a loyal relationship and long-term desire between the consumer and the brand as a satisfying consequence of experience [31]. In marketing and service literature, brand commitment is considered one of the most significant determinants in assessing the strength of marketing interactions and measuring subsequent consumer behaviors [32]. This finding implies that commitment is a positive mechanism for maintaining the consequences of positive actions [33,34]. Specifically, consumers with a high degree of brand commitment have a strong emotional attachment to the brand [35]. In addition, the triangular theory of love posits that commitment is an antecedent of love and is applied to explain relationships with the hotel brand [36,37].

2.2.3. Brand Love

The concept of brand love evolved from studies on consumer–brand relationships [38]. Brand love encompasses various positive emotions and attitudes that help to explain and predict changes in consumers’ post-consumption behaviors [39]. Many factors that affect brand love have also been reported in the literature. For example, Wang, Qu, and Yang [36] empirically tested the relationship between brand commitment and love in the context of hotel brand portfolios. Langner, et al. [40] showed that brand commitment enables customers to form a long-term relationship with the brand, through which the cumulative brand experience can improve consumers’ emotions of brand love. Consequently, customers’ commitment to a brand may gradually lead to their love for the brand.

Based on earlier studies on brand satisfaction, commitment, and love, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Brand satisfaction is positively correlated with brand commitment.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Brand satisfaction is positively correlated with brand love.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Brand commitment is positively correlated with brand love.

2.3. Customer Citizenship Behavior

CCBs are considered essential for maintaining the relationship between the brand and its customers [12], thereby retaining customers in the long term and eventually improving brand performance [41]. CCBs refer to customers’ discretionary and prosocial behaviors that benefit service providers (e.g., luxury hotels) [9,11]. Specifically, customers can support employees or other customers by providing constructive comments to the organization and suggesting ways to enhance its performance or services [42]. CCB is also referred to as voluntary customer performance and extra-role customer behaviors [43]. When customers feel satisfied or love a brand, they are more likely to spread positive word-of-mouth and feedback on the improvement of the brand, help with brand publicity, tolerate failure, and resist negative information [44]. With these conceptualizations of CCBs in previous literature, the current study defines CCBs as a second-order construct via four sub-constructs (i.e., helping, advocacy, tolerance, and feedback).

Given that CCBs could be important for marketers, scholars have investigated several factors that determine and influence CCBs, such as brand commitment [9]. Indeed, brand commitment is also a voluntary attitude of customers, which is key to explaining the citizenship behaviors of the brand [45]. According to social identity theory, individuals dedicated to a brand would commit themselves to behaviors that promote the brand [46]. Consequently, individuals committed to a luxury hotel brand are more likely to develop positive behaviors toward services and brands.

To better examine the relationship between customer post-experience consequences and CCBs, this study adopts four sub-dimensions of CCBs: helping, advocacy, tolerance, and feedback [42]. These aspects can help to examine the impact of post-experience consequences on CCBs. Based on previous studies, this study hypothesized the following relationships:

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Brand satisfaction is positively correlated with customer citizenship behaviors.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Brand commitment is positively correlated with customer citizenship behaviors.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Brand love is positively correlated with customer citizenship behaviors.

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Questionnaire

The questionnaire used in this study consisted of three sections. The first part provided a description of the survey and asked a few questions to screen the survey respondents. As the key focus of the current study is on the luxury hotel experience, a screening question was included to ask whether the participants had visited one or more hotels in the past 3 years. Respondents were then asked to indicate whether they had experience with 30 global luxury hotel brands. Only those who had one or more experiences with luxury hotel brands could complete the survey questionnaire. For this study, 30 luxury hotel brands, mainly in the Greater China region, were selected based on official websites for hotel brands and other reference materials.

The second part of the survey included items constructed within the research framework. Measurement items that have been previously shown to be valid and reliable in the literature were adopted and slightly modified based on the study context. The experiential value scale, consisting of four sub-dimensions, was modified from the scale by Ryu, et al. [47] and Mathwick, Malhotra, and Rigdon [6]. Five scales derived from Westbrook and Oliver [48] were used to measure brand satisfaction. Furthermore, four brand commitment items were adopted from Sternberg [37] and Wang, Qu, and Yang [36]. Four items on brand love were adopted from Carroll and Ahuvia [38]. Similarly, survey items for the four sub-dimensions of CCBs were derived from Groth [49], Revilla-Camacho, et al. [50], and Yi, et al. [51]. All measurement items were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The last part of the survey asked about the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

The survey items were initially prepared in English and translated into Chinese by the first author of the current study. To verify the quality of the transition, the pretest was performed by 20 postgraduate students majoring in hospitality and tourism and being fluent in both English and Chinese. The online survey was mainly conducted in English but was presented in both Chinese and English to help some respondents better understand the contents.

3.2. Data Collection

The response data for this study were collected using an online survey, which is a quantitative research approach. Data were collected using convenience sampling by posting the survey link on social media platforms (e.g., WeChat) during the survey period. The target population was Chinese travelers who have visited a luxury hotel in the last 3 years. The survey was conducted for a period of 12 days in July 2020. The average response time was 6–8 min. A total of 379 people responded to our invitation to answer the survey, and 245 respondents completed the survey. Of these, 65 responses were excluded from the final study sample because (1) they failed to correctly answer our attention check questions in the questionnaire, (2) they were incomplete, and (3) they had the same answers for all measurement items. The remaining 180 participants were used for further empirical analysis and hypothesis testing, resulting in a response rate of 64.6% and an effective response rate of 47.5%.

3.3. Data Analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis was the main method used to evaluate the proposed hypotheses. PLS provides numerous advantages to researchers. It requires minimal restrictions on the measurement scale, sample size, and residual distribution. Thus, PLS is an effective approach for evaluating models with explicit variables and complicated relationships.

4. Results

4.1. Profiles of Respondents

The demographic characteristics of the participants were investigated to understand their characteristics. In our sample, there were more women (65%) than men (35%), and most respondents were aged 35 years or younger (77.7%). The majority of the respondents had at least an undergraduate degree (45%) or a master’s degree and above (48.3%), and 4.4% had a doctoral degree. The educational backgrounds of the respondents were relatively high. In addition, more than 41% of the respondents had a higher monthly income (more than RMB ¥ 10,000) than the national average. Consequently, the sample may be rich in customer groups. Of the respondents, 37.5% had experienced luxury hotels twice, whereas 33.8% had experienced luxury hotels three to five times. The main factors respondents considered when choosing a luxury hotel were geographical location (16.2%), quality of service (14.2%), price (14.2%), environment (13.1%), and facilities (13%).

4.2. Measurement Model

The measurement model assessed construct validity and reliability based on factor loading, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and the correlation between components (Table 1). First, the CR was used to measure internal consistency [52]. Table 1 shows that all CRs were higher than the threshold of 0.7, confirming internal consistency. Second, the factor loadings and AVE values for the latent constructs were used to determine convergent validity. All factor loadings were greater than the threshold of 0.7, and all AVEs were above the minimum value of 0.5 [52]. These findings support convergent validity. Finally, discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square root of the AVE with latent variable correlations [53] and the heterotrait–monotrait matrix [54]. Table 2 shows that the square roots of the AVEs were higher than the correlations, indicating discriminant validity. The values of the heterotrait–monotrait matrix were all <0.85, except for the value of brand love at 0.938 (Table 3). However, the value did not exceed 1 (95% confidence interval: [0.911–0.959]), indicating that the discriminant validity was still confirmed [54].

Table 1.

Factor loadings, CR, and AVE.

Table 2.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion and Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio.

Table 3.

Hypotheses testing.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

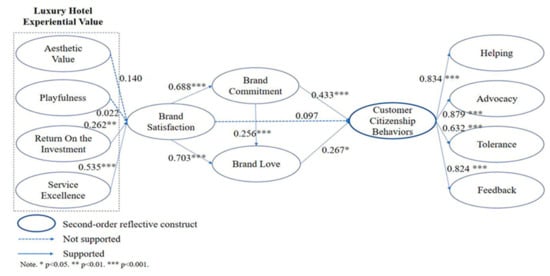

Using the PLS-SEM analysis (Figure 2, Table 3), the inner model shows that customers’ perceived aesthetic value did not substantially impact their satisfaction with luxury hotel brands (H1: β = 0.14, p > 0.05, f2 = 0.04). Thus, H1 is not supported. Similarly, playfulness did not significantly influence brand satisfaction (H2: β = 0.022, p > 0.05, f2 = 0.001). Hence, H2 was not supported. In contrast, the ROI value of the luxury hotel experience had a significant effect on customer brand satisfaction (H3: β = 0.262, p < 0.01, f2 = 0.123). Thus, H3 was confirmed, and the size of the effect was moderate. The excellence of luxury hotel services also significantly influences brand satisfaction (H4: β = 0.535, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.352). Hence, H4 was acceptable and had a strong effect size. The results revealed that brand satisfaction had a significant impact on brand commitment (H5: β = 0.688, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.899) and brand love (H6: β = 0.703, p < 0.001, f2 = 1.359), both of which had strong effect sizes. However, customers’ brand satisfaction did not positively impact their citizenship behavior (H8: β = 0.097, p > 0.05, f2 = 0.005). Thus, H5 and H6 were supported, but H8 was rejected. Simultaneously, brand commitment significantly influences brand love (H7: β = 0.256, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.181) and CCB (H9: β = 0.433, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.183). Hence, H7 and H9 were confirmed, and the effect sizes were moderate. Brand love also had a significant effect on CCB (H10: Î2 = 0.267, p < 0.05, f2 = 0.03). Hence, H10 was supported, but it has a low effect size.

Figure 2.

Results.

The explanatory power of customer experience value for brand satisfaction was 73.5%, that of brand satisfaction for brand commitment was 47%, and that of the two latent variables (brand satisfaction and brand commitment) for brand love was 80.6%. Simultaneously, the explanatory power of the three latent variables (brand satisfaction, commitment, and love) for CCBs was 53.5%. Therefore, this pattern explains the degree of the potential variables.

In addition to measuring adj. R2 to evaluate predictive accuracy, this study used the blindfolding procedure to determine the Stone–Geisser Q-squared (Q2) value to analyze cross-validated predictive relevance. The Q2 values of the eight endogenous variables used in this study were still within the acceptable levels, indicating that the model has predictive power (brand satisfaction = 0.584, brand commitment = 0.372, brand love = 0.660, CCB = 0.262).

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the role of customers’ perceptions of experiential value in creating post-experience consequences (brand satisfaction, commitment, and love) and citizenship behaviors in luxury hotels. The findings suggest that the luxury hotel experience could create customers’ perceptions of experiential value, which in turn enhances their brand experience evaluation (i.e., brand satisfaction), post-experience consequences (i.e., brand commitment and love), and subsequent behaviors (i.e., customer citizenship behaviors). These findings would suggest several theoretical and managerial implications for luxury hotels.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

In comparison with previous literature, this study’s results have several theoretical implications. First, unlike other studies proving the relationships between all four experiential values and satisfaction [55], the current study showed that only ROI and service excellence, two extrinsic values, were positively correlated with brand satisfaction. This result is possibly due to the context of this study, a luxury hotel experience where customers have higher expectations of service quality and return on investment as they need to pay a relatively higher price [56]. Aesthetic value and playfulness are considered essential foundations for hotel service experiences [7], which may no longer influence hotels’ competitiveness and service values in the luxury hotel context.

Second, the results of this study confirmed the role of brand satisfaction in promoting brand commitment, which eventually leads to brand love. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies [36,57,58]. These triangular relationships advocate the importance of brand experiential value and satisfaction in creating a positive emotional relationship (e.g., brand commitment and brand love) between hotel guests and the brand.

Third, this study explored the relationship between brand experience, brand satisfaction, brand commitment, and brand love, and ultimately its impact on CCBs. An extensive literature review confirmed the relationship between brand satisfaction and CCBs, or between brand commitment and CCBs [9,59]. Nevertheless, the current study confirms the positive relationships among the constructs proposed in the research framework. It is worth noting that the relationships between brand satisfaction and CCBs are fully mediated through brand commitment and brand love, emphasizing the important role of brand commitment and brand love in inducing customers’ positive subsequent behaviors in the luxury hotel context. This result can be explained by the fact that brand satisfaction is merely the accumulation of customer evaluation based on their interaction with the brand [28]. In contrast, brand commitment and brand love come from an emotional and behavioral connection between customers and the brand, thereby promoting the positive actions of customers and predicting subsequent customer behaviors [33,34,39].

5.3. Practical Implications

Managers of luxury hotels need to develop customer–brand relationships to achieve sustainable and stable growth under fierce competition. Thus, the findings of this study have managerial implications.

First, luxury hotel experiences should be designed in a way to reflects customers’ needs. To do so, hotel managers need to concentrate on customers’ perceptions of return on investment and service excellence when designing service experiences at luxury hotels. For example, considering the core of luxury hotel experiences, luxury hotel guests might expect a high level of service excellence. High-touch services (e.g., hospitality, welcoming attitude) should be at the core of hotel guest experiences that need to be focused upon [60]. At the same time, the return on investment needs to be considered. The price for luxury hotels is usually higher than other types of accommodation [61]. Furthermore, hotel managers need to launch preferential or membership activities to meet the economic and psychological needs of consumers so that they can better experience hotel services. In addition, as service performance by hotel employees is regarded as an important factor in the perception of service quality, special attention is required for human relations and the development of luxury hotels.

Second, this study confirmed the relationships between brand satisfaction, commitment, and love, which lead to customers’ subsequent behaviors (e.g., CCBs). In line with these results, luxury hotels could utilize their customers’ brand commitment and love, which are psychological and emotional connections between hotel guests and the brand, to compete in an extremely competitive environment. In other words, hotel managers and marketers should focus more on brand commitment (i.e., the behavioral aspect) and brand love (i.e., the emotional aspect) than a mere increase in brand satisfaction. To do so, hotel managers can utilize various marketing and promotional activities such as brand extension, co-creation of service products, and various experiential components at a luxury hotel. These managerial activities would eventually result in CCBs, such as helping other customers, being ambassadors, and/or providing constructive feedback.

Third, the current study’s findings could have an impact on social media marketing activities. Earlier studies [62] showed that consumers’ voluntarily engaged behaviors with brands would increase brands’ performance, such as brand awareness and purchase intention. Such positive brand performances can be achieved through consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs) [62,63,64]. Luxury hotel visitors having brand engagement and love would be more willing to participate in online brand-related activities that lead to CCBs.

Fourth, the findings of this study could provide useful information for impactful changes in the hotel industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to social distancing practices operated by governments and the fear of physical contact during the COVID-19 pandemic, many hotels implemented a variety of technical improvements and changes to maintain the levels of their service quality, while reducing human contact and ensuring customer satisfaction. However, the results of the current study suggest that service excellence is an important influencing factor that increases brand satisfaction in luxury hotel settings. In the context of luxury hotels, becoming contactless or using advanced technologies (e.g., service robots and kiosks) may harm their brand reputation and service excellence (citation). Therefore, luxury hotels must ensure a way of maintaining the level of customers’ perceptions of service excellence, even with a contactless service experience.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Although the current study provides important theoretical and managerial implications, it has several limitations. First, it considered the context of luxury hotels as a study context while understanding the role of brand experiential value in inducing customers’ CCBs through brand satisfaction, brand commitment, and brand love. To generalize the findings, different study contexts (e.g., restaurants, chain hotels, or other service providers) could be used for further empirical verification. Similarly, this result may be solely due to the study population, which requires additional empirical studies based on different populations. Second, the study focused mainly on the relationships between experiential values and CCBs through brand satisfaction, brand commitment, and brand love. However, these relationships may omit several possible mediating variables such as brand intimacy, brand passion, perceived value, and customers’ co-creation behaviors. Future studies could extend the research framework proposed in this study by including these variables. Last, but not least, our sample could be problematic for the generalizability of our findings. Only 180 respondents were included in the empirical study, and the majority were relatively younger. Thus, future studies should be expanded to incorporate a broader population for better generalizability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Y.C.; data curation, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; project administration, Y.C.; writing—original draft, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the institution’s internal regulation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davidson, M.; Guilding, C.; Timo, N. Employment, flexibility and labour market practices of domestic and MNC chain luxury hotels in Australia: Where has accountability gone? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukusta, D.; Heung, V.C.; Hui, S. Deploying self-service technology in luxury hotel brands: Perceptions of business travelers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V.; Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, T.; Hsu, C.H. An improved model for sentiment analysis on luxury hotel review. Expert Syst. 2020, e12580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chathoth, P.K.; Ungson, G.R.; Harrington, R.J.; Chan, E.S. Co-creation and higher order customer engagement in hospitality and tourism services: A critical review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Balaji, M.; Soutar, G.; Jiang, Y. The antecedents and consequences of value co-creation behaviors in a hotel setting: A two-country study. Cornell Hosp. Q 2020, 61, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Lee, C.-K.; Back, K.-J.; Schmitt, A. Brand experiential value for creating integrated resort customers’ co-creation behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-T.S.; Wang, Y.-C. Experiential value in branding food tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L.; Pervan, S.J.; Beatty, S.E.; Shiu, E. Service worker role in encouraging customer organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Alves, H. Customer value co-creation in the hospitality and tourism industry: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M. Managing customer citizenship behavior: A relationship perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C.; Jost-Benz, M.; Riley, N. Towards an identity-based brand equity model. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-Y.; Aryee, S.; Law, K.S. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E.S.A.; Marzouk, W.G. Factors Affecting Customer Citizenship Behavior: A Model of University Students. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2018, 10, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.; Okumus, F.; Wang, Y.; Kwun, D.J.-W. Understanding the Consumer Experience: An Exploratory Study of Luxury Hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2011, 20, 166–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-H.E.; Wu, C.K. Relationships among experiential marketing, experiential value, and customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Booms, B.H.; Tetreault, M.S. The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, X.R.; DiPietro, R.; So, K.K.F. The creation of memorable dining experiences: Formative index construction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamossy, G.; Scammon, D.L.; Johnston, M. A preliminary investigation of the reliability and validity of an aesthetic judgment test. Adv. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 685–690. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, L.S.; Kernan, J.B. On the meaning of leisure: An investigation of some determinants of the subjective experience. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 9, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Goh, B. Experiential value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in full-service restaurants: The moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Lee, Y.-K.; Yoo, Y.-J. Predictors of relationship quality and relationship outcomes in luxury restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; Ross, M.; King, C. Brand fidelity: Scale development and validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grisaffe, D.B.; Nguyen, H.P. Antecedents of emotional attachment to brands. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H. Towards an understanding of ‘why sport tourists do what they do’. Sport Soc. 2005, 8, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpande, R. Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Sohal, A. An examination of the relationship between trust, commitment and relationship quality. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2002, 30, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, T.W.; Summers, J.O.; Acito, F. Relationship marketing activities, commitment, and membership behaviors in professional associations. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.T.; Mummalaneni, V. Bonding and commitment in buyer-seller relationships: A preliminary conceptualisation. Ind. Mark. Purch. 1986, 1, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Keh, H.T.; Pang, J.; Peng, S. Understanding and measuring brand love. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Advertising and Consumer Psychology (ACP), Santa Monica, CA, USA, 7–9 June 2007; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Qu, H.; Yang, J. The formation of sub-brand love and corporate brand love in hotel brand portfolios. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. A triangular theory of love. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 93, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, T.; Bruns, D.; Fischer, A.; Rossiter, J.R. Falling in love with brands: A dynamic analysis of the trajectories of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E.; Alexander, M. The role of customer engagement behavior in value co-creation: A service system perspective. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Hwang, J. The role of prosocial and proactive personality in customer citizenship behaviors. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Massiah, C.A. When customers receive support from other customers: Exploring the influence of intercustomer social support on customer voluntary performance. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 9, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.; Merunka, D. The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C.; Zeplin, S. Building brand commitment: A behavioural approach to internal brand management. J. Brand Manag. 2005, 12, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M. Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 517–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.R.; Kim, W.G. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A.; Oliver, R.L. Developing better measures of consumer satisfaction: Some preliminary results. Adv. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, M. Customers as good soldiers: Examining citizenship behaviors in internet service deliveries. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-Camacho, M.Á.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Cossío-Silva, F.J. Customer participation and citizenship behavior effects on turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T.; Lee, H. The impact of other customers on customer citizenship behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.-J.; Liang, R.-D. Effect of experiential value on customer satisfaction with service encounters in luxury-hotel restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkison, T.; Hemmington, N.; Hyde, K.F. Luxury accommodation–significantly different or just more expensive? J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2018, 17, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erciş, A.; Ünal, S.; Candan, F.B.; Yıldırım, H. The effect of brand satisfaction, trust and brand commitment on loyalty and repurchase intentions. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.A.; Wahid, N.A. The effects of satisfaction and brand identification on brand love and brand equity outcome: The role of brand loyalty. Eur. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, W.; Kwag, M.-S.; Bae, J.-S. Customers as partial employees: The influences of satisfaction and commitment on customer citizenship behavior in fitness centers. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2015, 15, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Bharwani, S.; Mathews, D. Techno-business strategies for enhancing guest experience in luxury hotels: A managerial perspective. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Balaji, M. Customer-perceived value influence on luxury hotel purchase intention among potential customers. Tour. Anal. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Muntinga, D.G.; Pontes, H.M.; Lukasik, P. Influencing COBRAs: The effects of brand equity on the consumer’s propensity to engage with brand-related content on social media. J. Strateg. Mark. 2021, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Leung, W.K.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Koay, K.Y. “I follow what you post!”: The role of social media influencers’ content characteristics in consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs). J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzeta, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. Motivations to use different social media types and their impact on consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs). J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 52, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).