Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Consumption from the Perspective of Companies, People and Public Policies

Abstract

1. Introduction

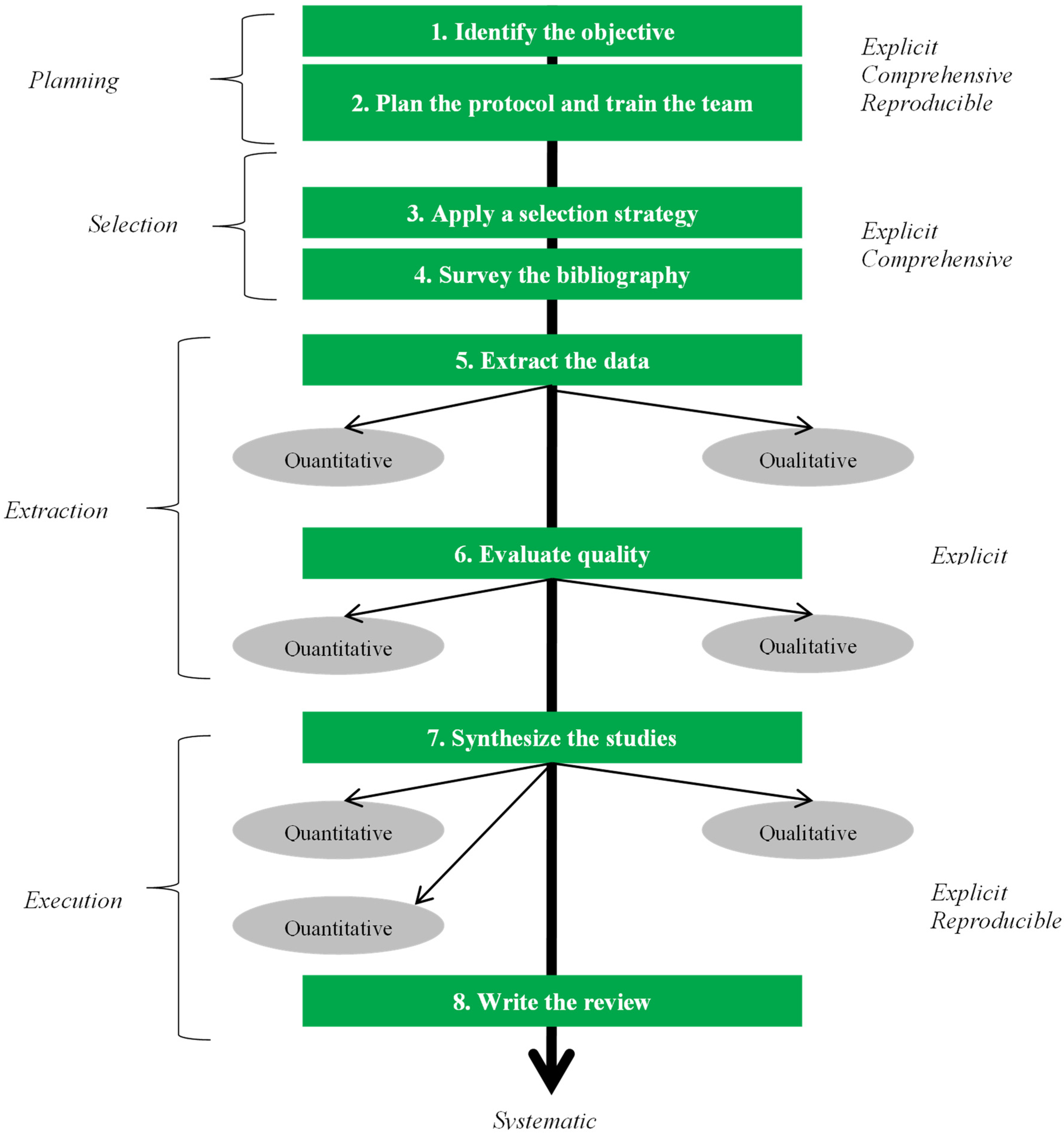

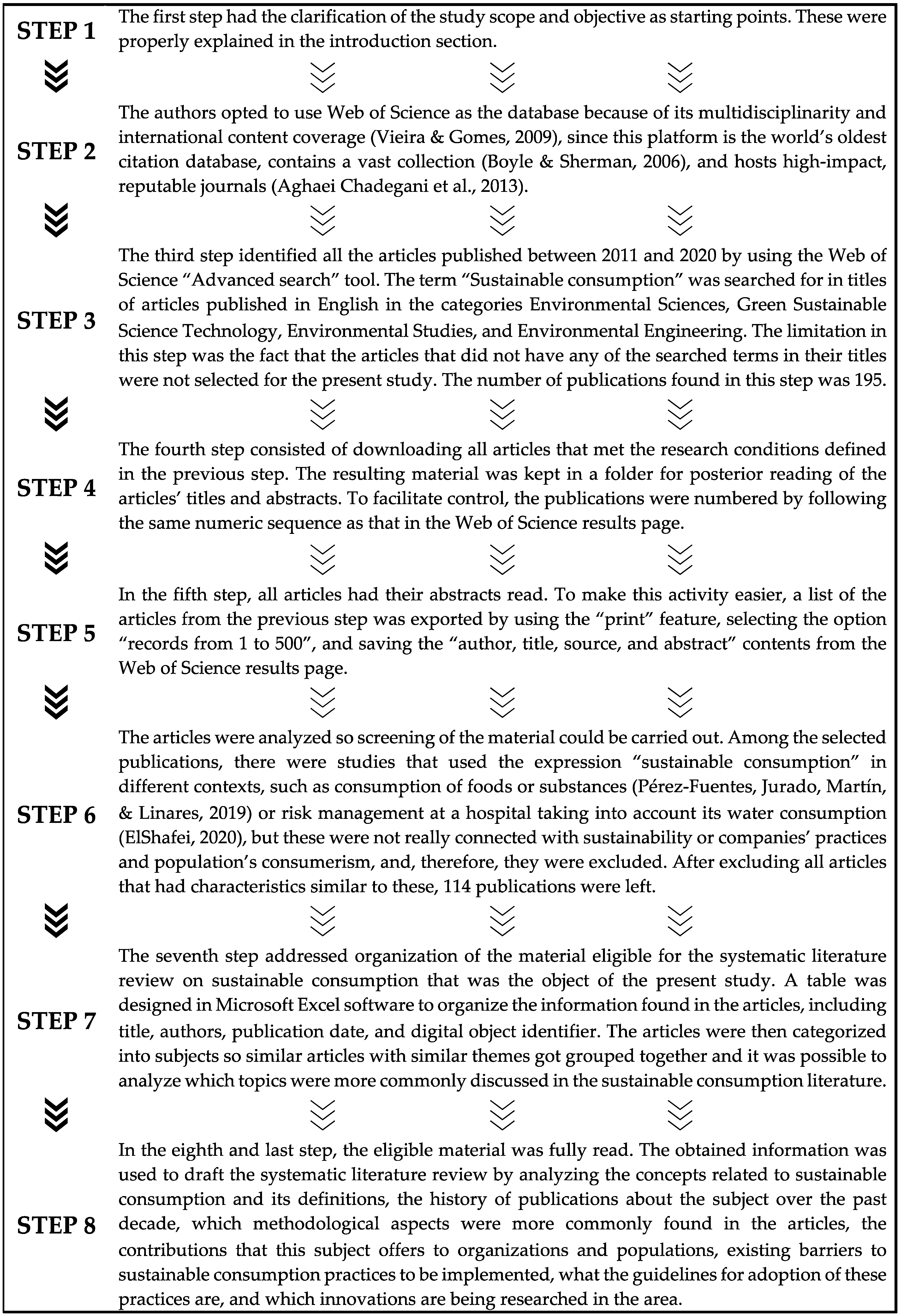

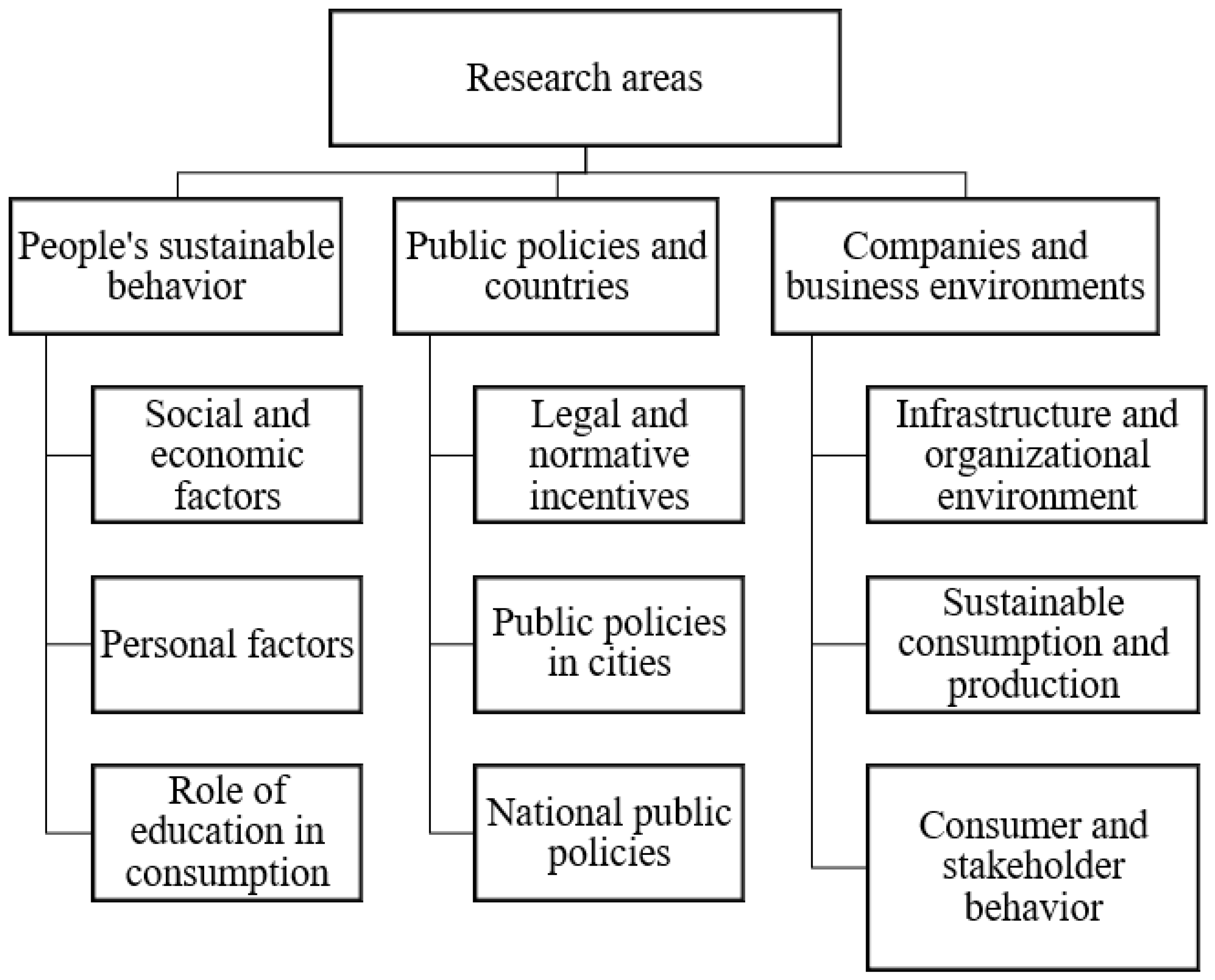

2. Materials and Methods

3. Systematic Literature Review

3.1. Definitions of Sustainable Consumption

3.2. Historical Evolution of Sustainable Consumption

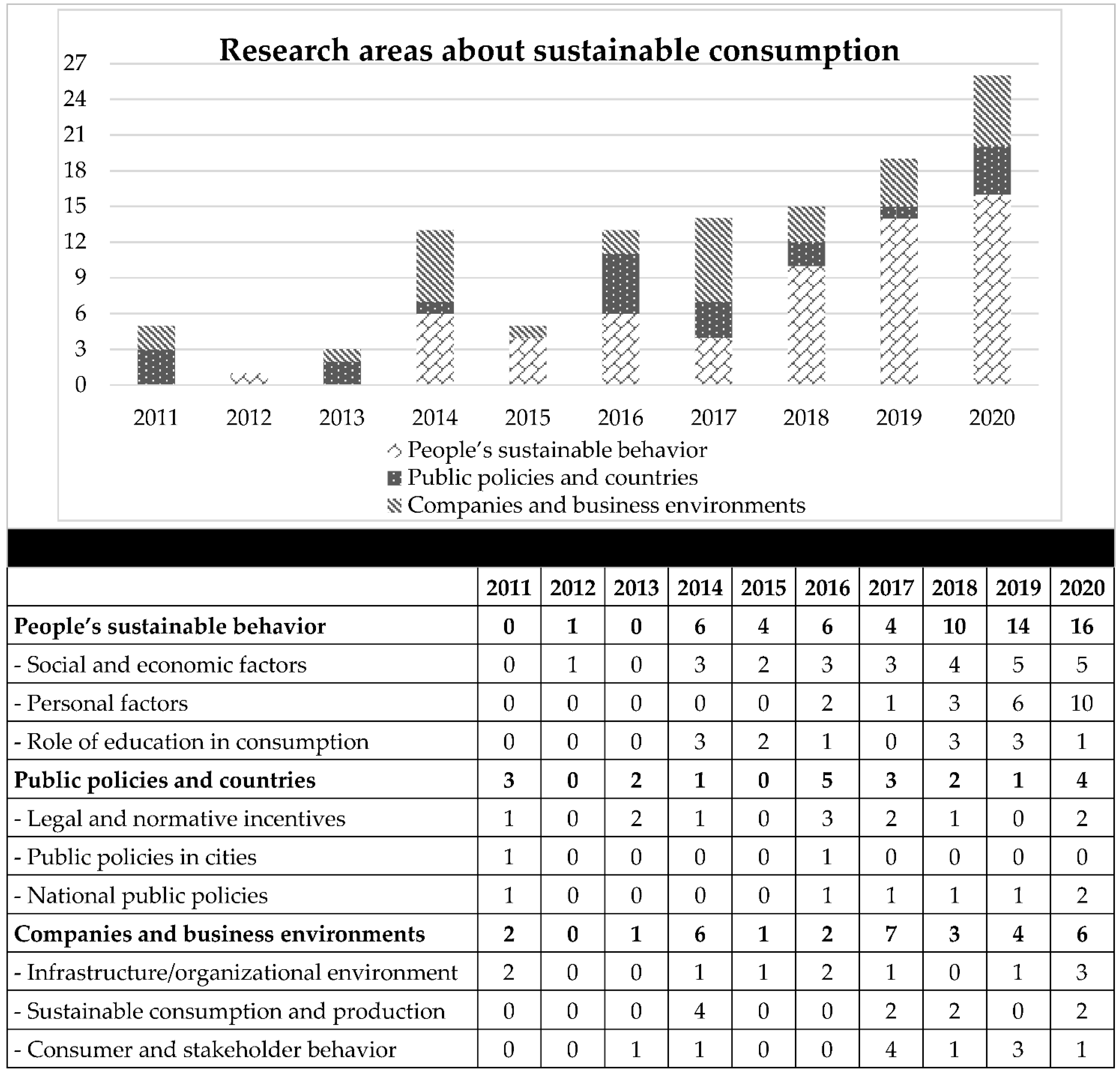

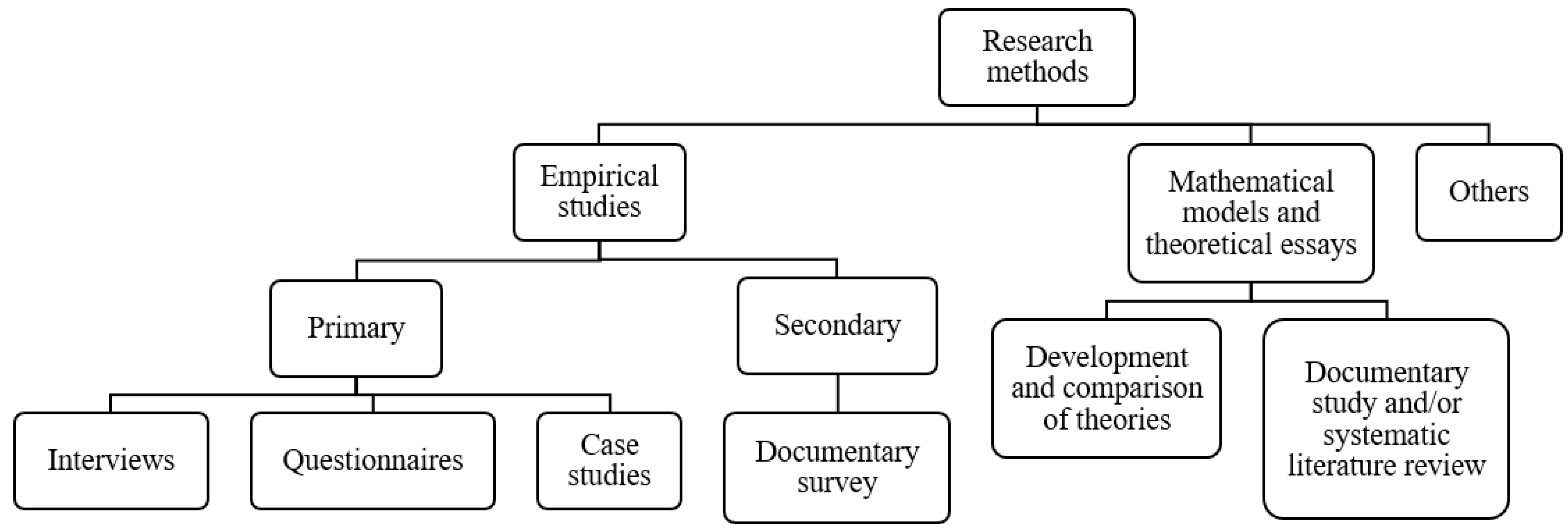

3.3. Sustainable Consumption from the Perspective of Used Materials and Methods

3.4. Contributions of Sustainable Consumption to Companies

3.5. Barriers to Adoption of Sustainable Consumption by Companies

3.6. Guidelines for Adoption of Sustainable Consumption by Companies

3.7. Sustainable Consumption-Related Innovations

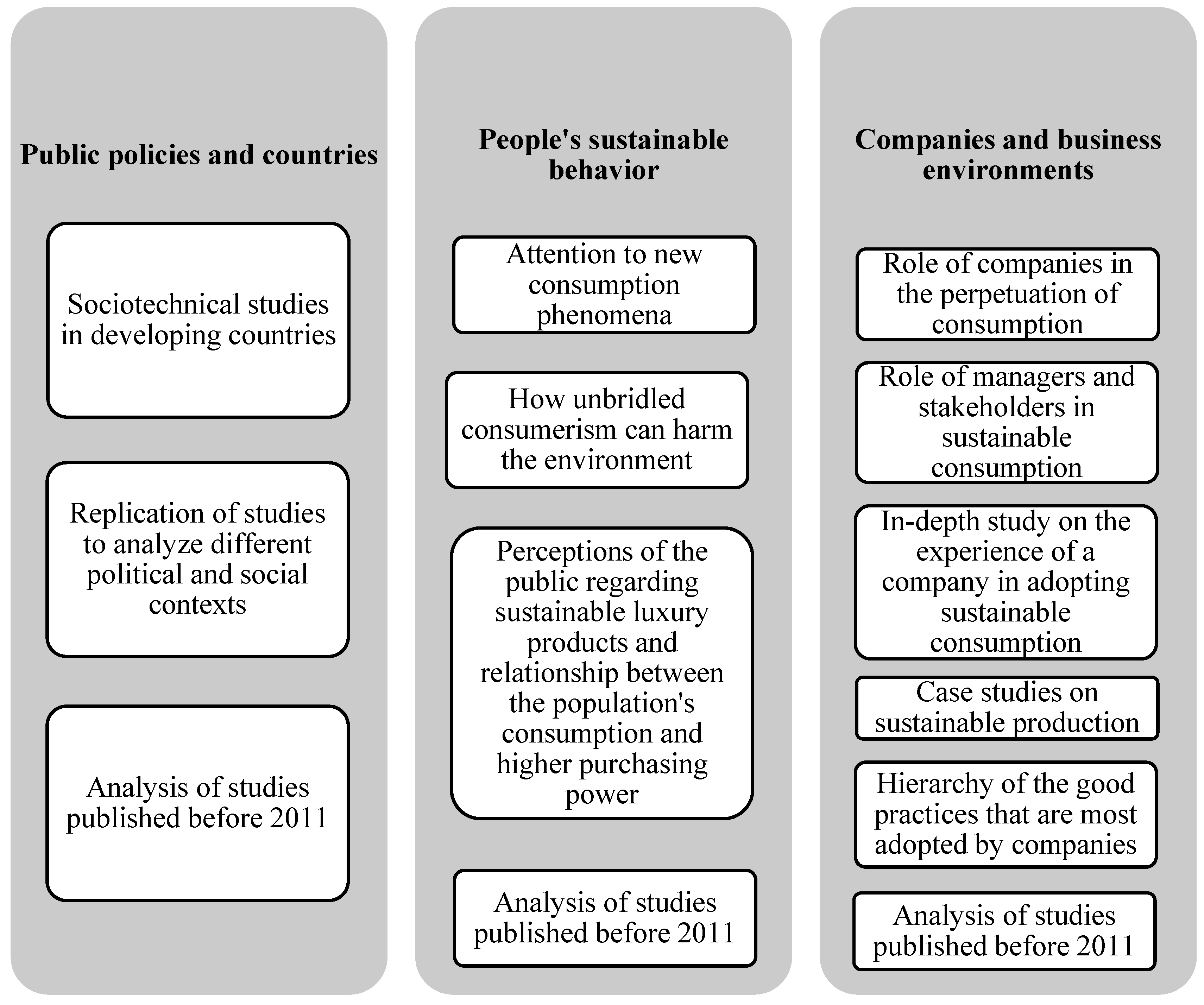

4. Agenda and Directions for Future Studies on Sustainable Consumption

5. Final Considerations

5.1. Theoretical Implications

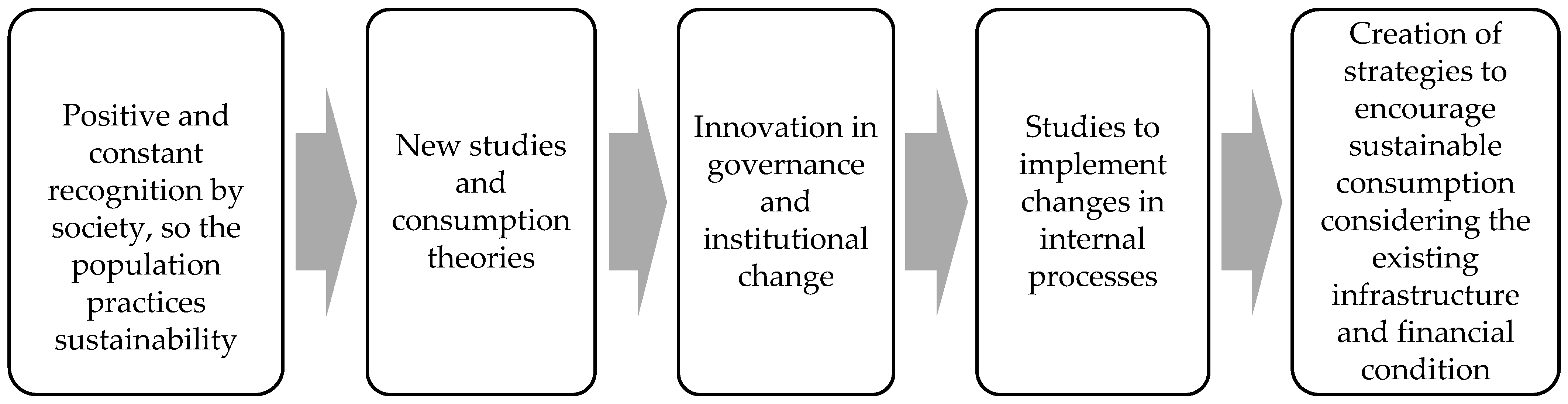

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- da Silva, M.E.; de Oliveira, A.P.G.; Gómez, C.R.P. Can collaboration between firms and stakeholders stimulate sustainable consumption? Discussing roles in the Brazilian electricity sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Papadopoulos, T.; Wamba, S.F.; Song, M. Towards a theory of sustainable consumption and production: Constructs and measurement. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman, M. Critical sustainable consumption: A research agenda. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2018, 8, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglia, D.; Lima, S.; Leocádio, L. An Alternative Theoretical Discussion on Cross-Cultural Sustainable Consumption. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.; Stanszus, L.S. Transforming Consumer Behavior: Introducing Self-Inquiry-Based and Self-Experience-Based Learning for Building Personal Competencies for Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Suárez, P.; Vega-Marcote, P.; Mira, R.G. Sustainable consumption: A teaching intervention in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2013, 15, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M.; Westhaus, M.; Morana, R. Conducting a Literature Review — The Example of Sustainability in Supply Chains. In Research Methodologies in Supply Chain Management; Kotzab, H., Seuring, S., Müller, M., Reiner, G., Eds.; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wee, B.; Banister, D. How to Write a Literature Review Paper? Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-La-Torre-Ugarte-Guanilo, M.C.; Takahashi, R.F.; Bertolozzi, M.R. Revisão sistemática: Noções gerais. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2011, 45, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, U.R.; Espindola, L.S.; da Silva, I.R.; da Silva, I.N.; Rocha, H.M. A systematic literature review on green supply chain management: Research implications and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badi, S.; Murtagh, N. Green supply chain management in construction: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.; Beecham, S.; Bowes, D.; Gray, D.; Counsell, S. A Systematic Literature Review on Fault Prediction Performance in Software Engineering. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2012, 38, 1276–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, J. Theory building through conceptual methods. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1993, 13, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Thorpe, R.; Lowe, A. Management Research—An Introduction; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chitu, C. A Guide to Conducting a Standalone Systematic Literature Review. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Islam, M.S.; Karia, N.; Fauzi, F.A.; Afrin, S. A literature review on green supply chain management: Trends and future challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agi, M.A.N.; Faramarzi-Oghani, S.; Hazır, Ö. Game theory-based models in green supply chain management: A review of the literature. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 59, 4736–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, G.; Kodali, R. A critical analysis of supply chain management content in empirical research. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2011, 17, 238–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.S.; Gomes, J.A.N.F. A comparison of Scopus and Web of Science for a typical university. Scientometrics 2009, 81, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, F.; Sherman, D. Scopus™: The product and its development. Ser. Libr. 2006, 49, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A.A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ebrahim, N.A. A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Jurado, M.D.M.M.; Martín, A.B.B.; Linares, A.J.J.G. Profiles of Violence and Alcohol and Tobacco Use in Relation to Impulsivity: Sustainable Consumption in Adolescents. Sustainability 2019, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElShafei, R. Managers’ risk perception and the adoption of sustainable consumption strategies in the hospitality sector: The moderating role of stakeholder salience attributes. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, I.; Matthies, E. Motivation and Impact. Implications of a Twofold Perspective on Sustainable Consumption for Intervention Programs and Evaluation Designs. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2014, 23, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.C.; Herter, M.M.; Rossi, P.; Borges, A. Going green for self or for others? Gender and identity salience effects on sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J. Mapping the movement to achieve sustainable production and consumption in North America. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Muñoz, P. Sharing cities and sustainable consumption and production: Towards an integrated framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, R.K.; Glavič, P.; Carpenter, A.; Virtič, P. Sustainable consumption and production—Research, experience, and development—The Europe we want. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.S.; Katz-Gerro, T. Urban public transport companies and strategies to promote sustainable consumption practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Rong, K.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T.F. Value Co-creation for sustainable consumption and production in the sharing economy in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 208, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderoni, S.; Perito, M.A. Sustainable consumption in the circular economy. An analysis of consumers’ purchase intentions for waste-to-value food. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Govindan, K.; Mangla, S.K. Structural model for sustainable consumption and production adoption—A grey-DEMATEL based approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarimoglu, E.; Binboga, G. Understanding sustainable consumption in an emerging country: The antecedents and consequences of the ecologically conscious consumer behavior model. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.; Hukkinen, J.I. Beyond effectiveness: The uses of Finland’s national programme to promote sustainable consumption and production. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1788–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtoranta, S.; Nissinen, A.; Mattila, T.; Melanen, M. Industrial symbiosis and the policy instruments of sustainable consumption and production. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.-C.; Lan, L.W.; Chang, K.-L. Sustainable consumption, production and infrastructure construction for operating and planning intercity passenger transport systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.; Aitken, R.; Mather, D. Conscientious consumers: A relationship between moral foundations, political orientation and sustainable consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, F. Does Internet penetration encourage sustainable consumption? A cross-national analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandra, T.K. Achieving triple dividend through mindfulness: More sustainable consumption, less unsustainable consumption and more life satisfaction. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 161, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legere, A.; Kang, J. The role of self-concept in shaping sustainable consumption: A model of slow fashion. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Rani, L. Social learning tools for environmentally sustainable consumption behavior in primary schools. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 5, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, T.; Stanszus, L.S.; Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness Training at School: A Way to Engage Adolescents with Sustainable Consumption? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valor, C.; Antonetti, P.; Merino, A. The relationship between moral competences and sustainable consumption among higher education students. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A. A consumption value-gap analysis for sustainable consumption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7714–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awais, M.; Samin, T.; Gulzar, M.A.; Hwang, J.; Zubair, M. Unfolding the Association between the Big Five, Frugality, E-Mavenism, and Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger-Erben, M.; Offenberger, U. A Practice Theory Approach to Sustainable Consumption. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2014, 23, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.K.; Govindan, K.; Luthra, S. Prioritizing the barriers to achieve sustainable consumption and production trends in supply chains using fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunn, V.; Bocken, N.; Hende, E.V.D.; Schoormans, J. Business models for sustainable consumption in the circular economy: An expert study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 212, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Yun, S.; Lee, J. Can Companies Induce Sustainable Consumption? The Impact of Knowledge and Social Embeddedness on Airline Sustainability Programs in the U.S. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3338–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, K.; Kokubu, K. Can firms enhance economic performance by contributing to sustainable consumption and production? Analyzing the patterns of influence of environmental performance in Japanese manufacturing firms. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 21, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, M.; Kokubu, K. A framework of sustainable consumption and production from the production perspective: Application to Thailand and Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.; Farrell, N.; Goodman, M.K. The cultural politics of climate branding: Project Sunlight, the biopolitics of climate care and the socialisation of the everyday sustainable consumption practices of citizens-consumers. Clim. Chang. 2019, 163, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catulli, M.; Cook, M.; Potter, S. Product Service Systems Users and Harley Davidson Riders: The Importance of Consumer Identity in the Diffusion of Sustainable Consumption Solutions. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Müller, M. Social Innovations for Sustainable Consumption and Their Perceived Sustainability Effects in Tehran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schappert, M.; von Hauff, M. Sustainable consumption in the smart grid: From key points to eco-routine. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 121585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendler, L. Sustainability Meta Labelling: An effective measure to facilitate more sustainable consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacko, M.; Martinuzzi, A.; Røpke, I.; Videira, N.; Antunes, P. Participatory systems mapping for sustainable consumption: Discussion of a method promoting systemic insights. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 106, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M. Making Sustainable Consumption and Production the Core of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2014, 6, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarque, C.; Charalambides, L.; Hilton, D.J.; Waroquier, L. Nudging sustainable consumption: The use of descriptive norms to promote a minority behavior in a realistic online shopping environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Kazantzidis, L. A sustainable consumption index/label to reduce information asymmetry among consumers and producers. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2016, 6, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stål, H.I.; Jansson, J. Sustainable Consumption and Value Propositions: Exploring Product-Service System Practices Among Swedish Fashion Firms. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pialot, O.; Millet, D.; Bisiaux, J. “Upgradable PSS”: Clarifying a new concept of sustainable consumption/production based on upgradablility. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülkü, M.A.; Hsuan, J. Towards sustainable consumption and production: Competitive pricing of modular products for green consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4230–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkabadi, A.M.; Pourjavad, E.; Mayorga, R.V. An integrated fuzzy MCDM approach to improve sustainable consumption and production trends in supply chain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solér, C.; Koroschetz, B.; Salminen, E. An infrastructural perspective on sustainable consumption—Activating and obligating sustainable consumption through infrastructures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. Cognitive, Affective and Conative Domains of Sustainable Consumption: Scale Development and Validation Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, V.; Gilmer, A. Developing a unified approach to sustainable consumption behaviour: Opportunities for a new environmental paradigm. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torma, G. How to Cope with Perceived Tension towards Sustainable Consumption? Exploring Pro-Environmental Behavior Experts’ Coping Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Sustainable consumption: How does social media affect food choices? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Barth, M. Key Competencies for and beyond Sustainable Consumption An Educational Contribution to the Debate. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2014, 23, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Q. Motivating sustainable consumption among Chinese adolescents: An empirical examination. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafell, G.; Banqué, N.; Viciana, S. Purchase and Use of New Technologies among Young People: Guidelines for Sustainable Consumption Education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. Theories of practices: Agency, technology, and culture: Exploring the relevance of practice theories for the governance of sustainable consumption practices in the new world-order. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanss, D.; Böhm, G.; Doran, R.; Homburg, A. Sustainable Consumption of Groceries: The Importance of Believing that One Can Contribute to Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, L. The impact of emotions on the intention of sustainable consumption choices: Evidence from a big city in an emerging country. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, I.; Valor, C.; Redondo, R. Do All Dimensions of Sustainable Consumption Lead to Psychological Well-Being? Empirical Evidence from Young Consumers. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic. 2020, 33, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yuan, Z. The effects of hedonic, gain, and normative motives on sustainable consumption: Multiple mediating evidence from China. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, R.; Akenji, L. Assessment of Policy Integration of Sustainable Consumption and Production into National Policies. Resources 2017, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Li, M.; Jia, H.; Guo, L. Developing More Insights on Sustainable Consumption in China Based on Q Methodology. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14211–14229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Dagiliūtė, R. The relationship between economic and carbon footprint changes in EU: The achievements of the EU sustainable consumption and production policy implementation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarzyńska, K. Evolutionary-economic policies for sustainable consumption. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 90, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P. Assessing effectiveness of governance approaches for sustainable consumption and production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gameren, V.; Ruwet, C.; Bauler, T. Towards a governance of sustainable consumption transitions: How institutional factors influence emerging local food systems in Belgium. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 874–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Promoting Sustainable Consumption Behaviors: The Impacts of Environmental Attitudes and Governance in a Cross-National Context. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 1128–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. Resource recovery and materials flow in the city: Zero waste and sustainable consumption as paradigms in urban development. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 2011, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizga, J.; Mishchuk, Z.; Golubovska-Onisimova, A. Sustainable consumption and production governance in countries in transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vringer, K.; Van Der Heijden, E.; Van Soest, D.; Vollebergh, H.; Dietz, F. Sustainable Consumption Dilemmas. Sustainability 2017, 9, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Taisch, M.; Mier, M.O. Influencing factors to facilitate sustainable consumption: From the experts’ viewpoints. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, E.; Lovio, R.; Jalas, M. Path creation for sustainable consumption: Promoting alternative heating systems in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Arita, S.; Joung, S. Advancing Sustainable Consumption in Korea and Japan—From Re-Orientation of Consumer Behavior to Civic Actions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, A.; Schweizer, C.R.; Defila, R.; Hirsch, P.; Burkhardt-Holm, P. “These Grandmas Drove Me Mad. It Was Brilliant!”—Promising Starting Points to Support Citizen Competence for Sustainable Consumption in Adults. Sustainability 2019, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y. Small is green? Urban form and sustainable consumption in selected OECD metropolitan areas. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, P.; Vergragt, P.; Brown, H.S.; Dendler, L.; Gorenflo, N.; Matus, K.; Quist, J.; Rupprecht, C.D.; Tukker, A.; Wennersten, R. Advancing sustainable consumption and production in cities—A transdisciplinary research and stakeholder engagement framework to address consumption-based emissions and impacts. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Technology acceptance perception for promotion of sustainable consumption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 6329–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caeiro, S.; Ramos, T.B.; Huisingh, D. Procedures and criteria to develop and evaluate household sustainable consumption indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 27, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, A.; Fuchs, D. Sustainable consumption corridors: Concept, objections, and responses. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2014, 23, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Luo, Z.; Wamba, S.F.; Roubaud, D.; Foropon, C. Examining the role of big data and predictive analytics on collaborative performance in context to sustainable consumption and production behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 1508–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineiro-Villaverde, G.; García-Álvarez, M.T. Sustainable Consumption and Production: Exploring the Links with Resources Productivity in the EU-28. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, D.; Yang, Z.; Ma, S. Unraveling customer sustainable consumption behaviors in sharing economy: A socio-economic approach based on social exchange theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, Y.D.A.S.; Fonseca, G.; Soares, A.D.F.; da Silva, E.C.N.; Ostanik, P.A.G.; Perobelli, J.E. Food-triad: An index for sustainable consumption. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, I.; Hameed, I. Promoting environmentally sustainable consumption behavior: An empirical evaluation of purchase intention of energy-efficient appliances. Energy Effic. 2020, 13, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger-Erben, M.; Rückert-John, J.; Schäfer, M. Sustainable consumption through social innovation: A typology of innovations for sustainable consumption practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Spangenberg, J.H. Needs, wants and values in China: Reducing physical wants for sustainable consumption. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nordlund, A.; Westin, K. Examining drivers of sustainable consumption: The influence of norms and opinion leadership on electric vehicle adoption in Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 154, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Sustainable consumption from the consumer’s perspective: Antecedents of solar innovation adoption. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Qi, Y. Factors influencing sustainable consumption behaviors: A survey of the rural residents in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bengtsson, M. Consumer motivations for sustainable consumption: The interaction of gain, normative and hedonic motivations on electric vehicle adoption. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Cai, C.; Fan, X. How does material possession love influence sustainable consumption behavior towards the durable products? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-García, E.C.; García-Machado, J.J.; Yábar, D.C.P.-B. Modeling the Social Factors That Determine Sustainable Consumption Behavior in the Community of Madrid. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M. Sustainable consumption and wellbeing: Does on-line shopping matter? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 1112–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansu-Mensah, P.; Bein, M.A. Towards sustainable consumption: Predicting the impact of social-psychological factors on energy conservation intentions in Northern Cyprus. Nat. Resour. Forum 2019, 43, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Xiaoling, G.; Ali, A.; Sherwani, M.; Muneeb, F.M. Customer motivations for sustainable consumption: Investigating the drivers of purchase behavior for a green-luxury car. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, C.; Weber, S.; Off, M.; Hackenberg, T.; Birk, C. Shedding Light on Realized Sustainable Consumption Behavior and Perceived Barriers of Young Adults for Creating Stimulating Teaching–Learning Situations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamad, N.R.; Ariffin, M. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards sustainable consumption among university students in Selangor, Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttel, A.; Ziesemer, F.; Peyer, M.; Balderjahn, I. To purchase or not? Why consumers make economically (non-)sustainable consumption choices. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J. Sustainable consumption in China: New trends and research interests. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, F.; Laurenti, R.; Meinherz, F.; Appio, F.P.; Mora, L. The Advent of Practice Theories in Research on Sustainable Consumption: Past, Current and Future Directions of the Field. Sustainability 2019, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukenna, S.; Nkamnebe, A.; Idoko, E. Inhibitors of sustainable consumption: Insights from university academic staff in southern Nigeria. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U.; Grossman, P. Meditating for the Planet: Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Sustainable Consumption Behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 1012–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piligrimienė, Ž.; Žukauskaitė, A.; Korzilius, H.; Banytė, J.; Dovalienė, A. Internal and External Determinants of Consumer Engagement in Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Horska, E.; Raszka, N.; Żelichowska, E. Towards Building Sustainable Consumption: A Study of Second-Hand Buying Intentions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarditi, C.; Hahnel, U.J.J.; Jeanmonod, N.; Sander, D.; Brosch, T. Affective Dilemmas: The Impact of Trait Affect and State Emotion on Sustainable Consumption Decisions in a Social Dilemma Task. Environ. Behav. 2018, 52, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkutė, G.; Staniškis, J.K. The role of different stakeholders in implementing sustainable consumption and production in Lithuania. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B.; Chekima, S.; SyedKhalidWafa, S.A.W.; Igau, O.A.; Sondoh, S.L., Jr. Sustainable consumption: The effects of knowledge, cultural values, environmental advertising, and demographics. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvenharju, S. Potential for a radical policy-shift? The acceptability of strong sustainable consumption governance among elites. Environ. Politi. 2020, 29, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tu, J.-C.; Jiang, Q. The Influential Factors of Consumers’ Sustainable Consumption: A Case on Electric Vehicles in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuni, J.A.; Du, J. Sustainable Consumption in Chinese Cities: Green Purchasing Intentions of Young Adults Based on the Theory of Consumption Values. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, T.M.; Goff, S.H.; Smaldino, P.E. The coevolution of economic institutions and sustainable consumption via cultural group selection. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severis, R.M.; Simioni, F.J.; Moreira, J.M.M.; Alvarenga, R.A. Sustainable consumption in mobility from a life cycle assessment perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, H.D. Toward a neoclassical theory of sustainable consumption: Eight golden age propositions. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 105, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuba, M. Upcycling as a Manifestation of Consumer and Business Behavior that Expresses Sustainable Consumption and Determines the Functioning of the Communal Services Sector. Probl. Ekorozw. 2018, 13, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Purnomo, M.; Daulay, P.; Utomo, M.R.; Riyanto, S. Moderating Role of Connoisseur Consumers on Sustainable Consumption and Dynamics Capabilities of Indonesian Single Origin Coffee Shops. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contributions to Companies | Author(s) |

|---|---|

| Suggested that governance models (environmental laws) can promote the mode of operation of industrial symbiosis. | Lehtoranta et al. [37] |

| Identified the need for mutual and complementary interaction between stakeholders. | Da Silva et al. [1] |

| Proposed the “meta labeling” system to make it easier for consumers to align their purchase decisions with sustainable development goals. | Dendler [58] |

| Contributed to the discussion about approaches to systemic thinking from the sustainable consumption perspective. | Sedlacko et al. [59] |

| Argued that SCP must be discussed by means of a political agenda. | Akenji and Bengtsson [60] |

| Explained how material values and social recognition influence sustainable consumption in the transcultural context. | Ceglia et al. [4] |

| Demonstrated the efficacy of descriptive rules when they influence pro-environmental behavior in the online shopping context. | Demarque et al. [61] |

| Showed the participation of Portuguese public transport companies in management and sustainability practices. | Cruz and Katz-Gerro [31] |

| Provided an evaluation instrument that assigned a score for the level of sustainability of companies (more specifically, for the products they offered) with the objective of decreasing information asymmetry between buyers and sellers. | Nikolaou and Kazantzidis [62] |

| Demonstrated the role played by managers when they deal with institutional pressures during SCP implementation, based on institutional theory and agency theory. | Dubey et al. [2] |

| Presented a structural model to analyze barriers to acceptance of insertion of SCP strategies in the supply chain. | Mangla et al. [49] |

| Explored the use of value propositions that shape sustainable consumption by means of examples of product-service systems. | Stal and Jansson [63] |

| Consolidated the mode of consumption and production based on the upgrade capacity of product-service systems (upgradable product-service systems). | Pialot et al. [64] |

| Showed consumers’ acceptance of product-service systems. | Catulli et al. [55] |

| Contributed to a structure focused on adoption of SCP to help regulatory agencies, managers, consumers, and policymakers. | Luthra et al. [34] |

| Sought to elucidate the intricate relationships between sustainability, operations, and marketing by discussing customization of sustainable products and how these products can generate demand as a result of personalization and durability. | Ulku and Hsuan [65] |

| Listed the main barriers identified in each dimension (internal and external) faced by companies. | Torkabadi et al. [66] |

| Suggested that business models allow for achieving sustainable consumption. | Tunn et al. [50] |

| Contributed to the perception that companies that achieve better environmental performance are more likely to disseminate environmental information. | Nishitani and Kokubu [52] |

| Sought to elucidate how purchase and use of sustainable services can replace unsustainable alternatives. | Soler et al. [67] |

| Suggested that each market requires their own SCP policies, depending on the economic growth level. | Yagi and Kokubu [53] |

| Sought to explain the factors that contribute to sustainable consumption in specific segments of the market and help companies incorporate sustainability into their activities to improve their image and reduce their impact. | Quoquab & Mohammad [68] |

| Suggested that international companies need to assess the motivations of consumers that cause them to engage in sustainable consumption in the countries where these corporations develop their activities and evaluate the absolute impacts of the sustainability of their initiatives. | Iran and Müller [56] |

| Pointed out that companies can adopt smart grids, since new technologies expand consumer scope, leading to new sustainable consumption opportunities. | Schappert and von Hauff [57] |

| Research Area | Barrier | Author(s) |

|---|---|---|

| People’s sustainable behavior | Lack of knowledge and resistance to changing habits | Byers and Gilmer [69], Torma [70], Simeone and Scarpato [71] |

| Role of education | Fischer and Barth [72], Geng, Liu, and Zhu [73], Calafel, Banqué, and Viciana [74], Iran and Müller [56] | |

| Difficulty analyzing the variables that influence consumption | Spaargaren [75], Hanss, Böhm, Doran, and Homburg [76], Wang and Wu [77], Carrero, Valor, and Redondo [78], Tang, Chen, and Yuan [79], Quoquab and Mohammad [68] | |

| Public policies and countries | Lack of incentives in developing countries | Koide and Akenjii [80], Yarimoglu and Binboga [35] |

| Role of governments | Qu, Li, Jia, and Guo [81], Liobikiene and Dagiliute [82] | |

| Companies and business environments | Problems with finances | Solér, Koroschetz, and Salminen [67] |

| Technology in isolation does not bring the necessary changes | Safarzyńska [83] | |

| Corporate governance | Schroeder [84], Van Gameren, Ruwet, and Bauler [85], Wang [86] | |

| Influence of consumers, policies, and society as a whole | Lehmann [87], Brizga et al. [88], Vringer et al. [89] | |

| Existence of few studies to understand the practice | Stål and Jansson [63] |

| Research Area | Authors | Presented Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| People’s sustainable behavior (Social and economic factors) | Caeiro et al. [97] | Developing an approach to defining the main steps and criteria for formulation and evaluation of “sustainable household consumption” by means of sets of indicators. |

| Di Giulio and Fuchs [98] | Determining how realistic the approach “sustainable consumption corridors” would be to increase the feasibility of sustainable consumption, both empirically and politically. | |

| Companies and business environments (Infrastructure and organizational environments) | Dubey et al. [99] | Offering predictive analysis of collaborative performance metrics of companies that have practices related to sustainable consumption. |

| Biswas and Roy [96] Catulli, Cook, and Potter [55] | Addressing use of new technologies for creation of new metrics, methods of production, and ways to disseminate information on sustainable consumption. | |

| Public policies and countries (national public policies) | Lukman, Glavič, Carpenter, and Virtič [30] | Reporting positive results about sustainable consumption in developing countries. |

| Byers and Gilmer [69] | Creating a conceptual structure to address systematic, structural, and institutional perspectives on how consumption, by means of public policy initiatives, can be developed to reflect a deeper ecological basis. | |

| Pineiro-Villaverde and García-Álvarez [100] | Listing proposals oriented toward actions directly related to SCP, such as promoting use of recycled raw material in public works or requiring Ecolabel certification for agreements with public administrations. | |

| Public policies and countries (legal and normative incentives) | Wang et al. [101] | Pioneering in the explanation of roles, behaviors, and strategies related to sustainable consumption in a sharing economy context. |

| Guido et al. [102] | Developing a food labeling index to promote sustainable consumption. The index is calculated by classifying several resources in the environmental, health, and nutritional dimensions of target products in relation to a reference value. |

| Topics Recommended as Research Opportunities | Researcher(s) That Followed These Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Business dynamics | Sedlacko et al. [59], Doyle, Farrell, and Goodman [54], Schappert and von Hauff [57] |

| “Greenwashing” driving forces | Kim et al. [51] |

| Influence of choices and behaviors of consumers on environmental quality | Wang et al. [108], Torma [70] |

| Environmental problems and human behavior | Alvarez-Suarez et al. [6] |

| Social innovations and sustainable consumption | Jaeger-Erben et al. [104], Iran and Müller [56] |

| Attitudes implicit in green consumer behavior | Ceglia et al. [4] |

| Behavioral SCP model | Dubey et al. [2] |

| Consumption-value gaps and sustainable consumption behavior | Biswas [46] |

| Consumer behavior | Rezvani et al. [109], Dhandra [41] |

| “Material possession love” consumer behavior | Dong et al. [110] |

| Sustainable consumption behavior concept | Figueroa-Garcia et al. [111] |

| Sustainable consumption and online shopping | Guillen-Royo [112] |

| Behavioral control | Ansu-Mensahe and Bein [113], Simeone and Scarpato [71] |

| Motivation to consume for status | Ali et al. [114] |

| Adults and young people’s sustainable creative competence | Kreuzer et al. [115] |

| Rational action theory | Yarimoglu and Binboga [35] |

| Values, motivations, and paths involved in the engagement of people who adopt low-carbon lifestyles | Carrero et al. [78] |

| Topics Recommended for Study | Authors |

|---|---|

| Expanding mental models | Sedlacko et al. [59] |

| Exploring other characteristics of consumers | Kim et al. [51] |

| Improving questionnaire design and sample selection | Wang et al. [108] |

| Developing new studies on adoption of alternative routines and practices | Jaeger-Erben et al. [104] |

| Identifying how transcultural differences can create a powerful and synergic system to promote sustainable consumption | Ceglia et al. [4] |

| Improving the study by using several case studies or alternative methods and theories | Dubey et al. [2] |

| Replicating the study to test generalization in other samples | Biswas [46] |

| Examining the effect of motivations that lead to pro-environmental behavior in a more representative sample | Rezvani et al. [109] |

| Analyzing the different variables to help understand the relationship between material possession love and sustainable consumption behavior | Dong et al. [110] |

| Identifying the variables and projecting scales to measure them | Figueroa-Garcia et al. [111] |

| Exploring how “mindfulness” practices can encourage sustainable consumption in schools | Bohme et al. [44] |

| Analyzing levels of knowledge and attitudes related to sustainable consumption in students at other universities, taking into account the characteristics of these spaces | Ahamad and Ariffin [116] |

| Replicating the study on the role of big data in the collaborative performance of partners in sustainable consumption programs by collecting longitudinal data | Dubey et al. [99] |

| The approach used in the interview failed to consider the specific factors of the context, which left opportunities for future studies | Huttel et al. [117] |

| Carrying out in-depth analysis of each subdomain to offer detailed suggestions about the topics addressed | Shao [118] |

| Evaluating adherence of additional research areas and development of sociotechnical studies | Ma et al. [32] |

| Bridging the gaps in “practice theory” research fields; more specifically, addressing how results of the application of this theory differ from those obtained in studies on sustainable behaviors | Corsini et al. [119] |

| Examining people with low levels of education to determine to what extent noneducational factors can act as sustainable consumption drivers | Ukenna et al. [120] |

| Seeking to confirm the causal relationship between online shopping and well-being | Guillen-Royo [112] |

| Examining and analyzing the actual behavior of consumers and connecting the results with the data reported in the original study | Ansu-Mensahe and Bein [113] |

| Examining the additional cultural dimensions to obtain more insights | Ali et al. [114] |

| Collecting data from interviewees of different levels of education, ages, and cultural origins | Dhandra [41] |

| Empirically testing improvement in sustainable behavior | Kreuzer et al. [115] |

| Empirically testing sustainable consumption behavior | Yarimoglu and Binboga [35] |

| Giving more emphasis to relationships inherent in “mindfulness” and ethical values | Geiger et al. [121] |

| Future studies can use the model to compare knowledge of and interest in sustainable products between young people and older people | Legere and Kang [42] |

| Considering the effect of “self-caused” and “caused” factors | Han [122] |

| Examining how these moral competencies are developed, paying special attention to gender-based differences | Valor et al. [45] |

| Repeating the study in other countries and with samples that are representative of different age groups | Piligrimiene et al. [123] |

| Developing new studies on second-hand product attitudes, social standards, intentions, and behavior to deepen knowledge about pro-environmental behavior | Borusiak et al. [124] |

| Considering profiles of other types of consumers and identifying whether the results of the new studies agree with those of the original | Awais et al. [47] |

| Developing new studies on environmental performance by especially taking into account sustainable development goals and SCP | Nishitani and Kokubu [52] |

| Exploring the potential of emotional mechanisms in the sustainability domain | Tarditi et al. [125] |

| Considering empirical validation of the behavior | Kapoor and Dwivedi [107] |

| Addressing the mediator effect of cultural facilitation and focal constructs in countries where sustainable consumption is well-established | Carrero et al. [78] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Oliveira, U.R.; Gomes, T.S.M.; de Oliveira, G.G.; de Abreu, J.C.A.; Oliveira, M.A.; da Silva César, A.; Aprigliano Fernandes, V. Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Consumption from the Perspective of Companies, People and Public Policies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113771

de Oliveira UR, Gomes TSM, de Oliveira GG, de Abreu JCA, Oliveira MA, da Silva César A, Aprigliano Fernandes V. Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Consumption from the Perspective of Companies, People and Public Policies. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):13771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113771

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Oliveira, Ualison Rébula, Thaís Stiegert Meireles Gomes, Geovani Gabizo de Oliveira, Júlio Cesar Andrade de Abreu, Murilo Alvarenga Oliveira, Aldara da Silva César, and Vicente Aprigliano Fernandes. 2022. "Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Consumption from the Perspective of Companies, People and Public Policies" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 13771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113771

APA Stylede Oliveira, U. R., Gomes, T. S. M., de Oliveira, G. G., de Abreu, J. C. A., Oliveira, M. A., da Silva César, A., & Aprigliano Fernandes, V. (2022). Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Consumption from the Perspective of Companies, People and Public Policies. Sustainability, 14(21), 13771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113771