Do Financial Support Policies Catalyse the Development of New Consumption Field?—Evidence from China’s New Consumer Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

3. Empirical Strategies and Data

3.1. Data Sources and Sampling

3.2. Setting of the Econometric Model

3.3. Description of Major Variables

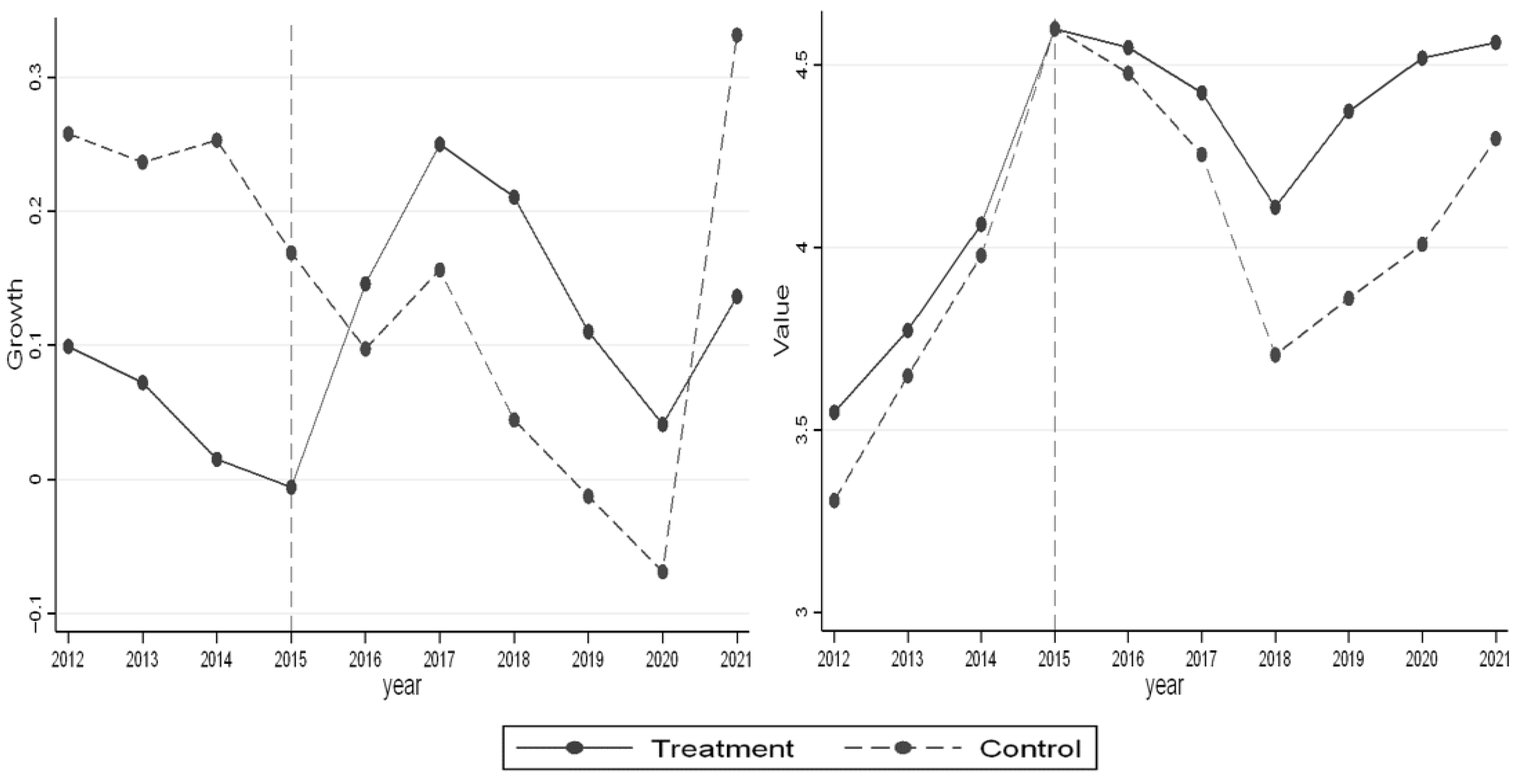

- Current Growth of Enterprises:Most studies estimated enterprise growth through financial characteristics such as sales revenue, profit margin, and cash flow, as well as non-financial characteristics such as marketing ability, R&D capacity, and market share [58,59,60]. Given that the supply and demand reinforce each other and demonstrate a constant increase in the context of China’s supply-side structural reform, this paper, with reference to the research of Delmar et al. [61], Onguka et al. [62], and Temel and Forsman [63], estimated the current growth of new consumer enterprises from two dimensions, i.e., revenue growth (Growth) and market value of listed enterprises (Value).

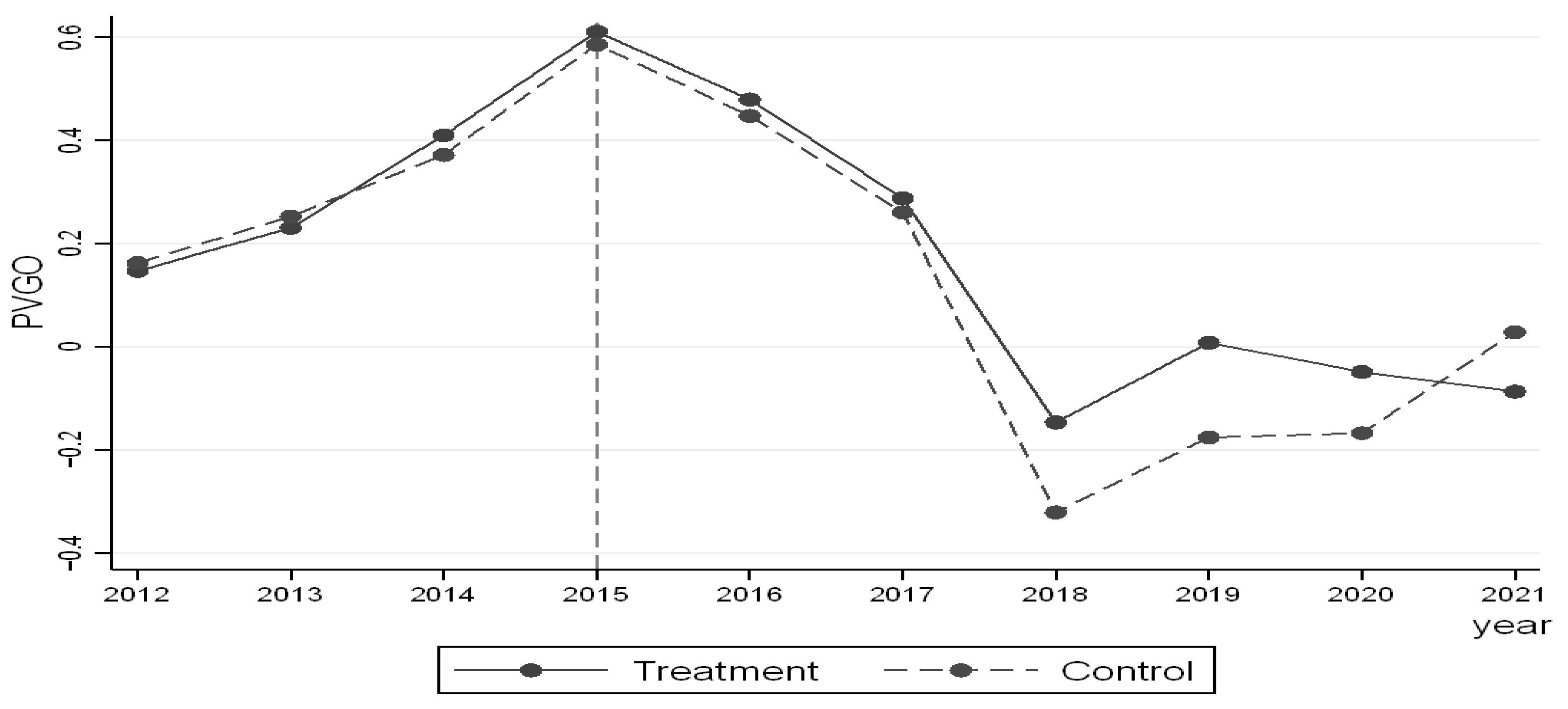

- Growth Potential of Enterprises:We examined the growth potential of enterprises through the present value of growth opportunities (PVGO), which is conceptually the difference between a market value minus a book value divided by the market value [64]. If the capital market is functional, then the available information will be precisely conveyed according to PVGO, which is the best way to estimate the present value of a company’s expected earnings (risks) [39].

- Controlled Variables:The growth of an enterprise may be influenced by its size, financial leverage, profitability, and duration [61], and the key new consumption areas may enjoy tax incentives from the government. Therefore, we controlled the influences of the abovementioned variables in the econometric regression, where size (Size) is measured using the natural logarithm of the total assets; financial leverage (Leverage) is the debt to asset ratio; profitability (Return) is determined by the return on equity; duration (Lage) is the logarithmic difference between the sample year minus the establishment year; and tax policy (Tax) is expressed by the actual income tax-to-total pre-tax profit ratio. At the same time, since business growth may also be affected by the macroeconomy in a region, we controlled the GDP growth rate (GDP) and local public financial revenue (Lrevenue) of the provinces in which enterprises were located.

4. Analysis of the Main Empirical Results

4.1. Financial Support Policies and the Growth of New Consumer Enterprises

4.2. Further Analysis on the Mechanism of Action

4.3. Robustness Check

4.3.1. Parallel Trend Test

4.3.2. Replacing the Control Group

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Analysis of Property Right Heterogeneity Based on Ownership

5.2. Analysis of North–South Geographic Heterogeneity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kee, H.L.; Tang, H. Domestic Value Added in Exports: Theory and Firm Evidence from China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 1402–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajderska, A.; Kapuściński, M. Macroeconomic Spillover Effects of the Chinese Economy. Rev. Int. Econ. 2020, 28, 992–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Y.; Lingxiao, T. Theory of the Development Pattern of Great Powers: Formation, Framework and Modern Value. Econ. Res. J. 2022, 57, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.; Xie, C.; Ye, X. China’s New Consumption in the New Era: Theoretical Connotation, Development Characteristics and Policy Orientation. Economist 2020, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guideline on Accelerating the Cultivation of New Supply and Driving Force Actively Led by New Consumption. The State Council of China. 2015. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2015/content_2975882.htm (accessed on 19 November 2015).

- Tao, S. The Rise of “New Consumption” Drives China’s Domestic Demand and Consumption Upgrading. Jilin Provincial Government Development Research Center. 2019. Available online: http://fzzx.jl.gov.cn/gzdt/yjdt/201912/t20191219_6329882.html (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Liao, H.; Zhang, L. New Consumption Promotes the Transformation and Upgrading of the Industrial Structure. People’s Trib. 2019, 27, 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Xianchun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, H. China’s New Economy: Roles, Characteristics and Challenges. Financ. Trade Econ. 2020, 41, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Qu, L. Do Green Policies Catalyze Green Investment? Evidence from ESG Investing Developments in China. Econ. Lett. 2021, 207, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines on Increasing Financial Supports in New Consumption Aeras. The People’s Bank of China; China Banking Regulatory Commission. 2016. Available online: http://www.pbc.gov.cn/goutongjiaoliu/113456/113469/3041026/index.html (accessed on 30 March 2016).

- King, R.G.; Levine, R. Finance and Growth: Schumpeter Might Be Right. Q. J. Econ. 1993, 108, 717–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.E. Using Monetary Policy to Stabilize Economic Activity. Financ. Stab. Macroecon. Policy 2009, 245, 296. [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, M. Macroeconomic Effects of Financial Stress and the Role of Monetary Policy: A VAR Analysis for the Euro Area. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2016, 13, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Wilson, A.; Halari, A. The Efficacy of Macroeconomic Policies in Resolving Financial Market Disequilibria: A Cross-country Analysis. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 24, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, P.; Eggertsson, G.B.; Romei, F. Dynamic Debt Deleveraging and Optimal Monetary Policy. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2020, 12, 310–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, E.J.; Diemont, E.; Stobbelaar, D.J.; Timmermans, W. Sustainable Green Urban Planning: The Workbench Spatial Quality Method. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2011, 4, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churm, R.; Radia, A.; Leake, J.; Srinivasan, S.; Whisker, R. The Funding for Lending Scheme. Bank Engl. Q. Bull. 2012, 18, Q4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z. Do the Green Credit Guidelines Affect Renewable Energy Investment? Empirical Research from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Chen, Y.; Lin, K. Does Access to Credit Availability Encourage Corporate Innovation?—Evidence From the Geographic Network of Banks in China. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Benfratello, L.; Schiantarelli, F.; Sembenelli, A. Banks and Innovation: Microeconometric Evidence on Italian Firms. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 90, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruta, D. Bank Loan Availability and Trade Credit for Small Businesses During the Financial Crisis. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2015, 55, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, I.; Martínez Pería, M.S. How Bank Competition Affects Firms’ Access to Finance. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2014, 29, 413–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhou, H.; Gao, Y.; Guan, Y. Digital Inclusive Finance, Human Capital and Inclusive Green Development—Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Impact of Government Intervention in the Housing Market: Evidence from the Housing Purchase Restriction Policy in China. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Xia, Y.; Fan, Y.; Lin, S.M.; Wu, J. Assessment of a Green Credit Policy Aimed at Energy-intensive Industries in China Based on a Financial CGE Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 163, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lei, X.; Long, R.; Zhao, J. Green Credit, Financial Constraint, and Capital Investment: Evidence from China’s Energy-intensive Enterprises. Environ. Manag. 2020, 66, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doh, S.; Kim, B. Government Support for SME Innovations in the Regional Industries: The Case of Government Financial Support Program in South Korea. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L. Are Small Businesses Worthy of Financial Aid? Evidence from a French Targeted Credit Program. Rev. Financ. 2013, 18, 877–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; He, L.; Yang, G. Targeted Monetary Policy and Financing Constraints of Chinese Small Businesses. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 2107–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.; Minh Vu, H.; Cong, M.; Hon Wei, L.; Islam, M.M.; Niedbała, G. Natural Resources Commodity Prices Volatility and Economic Performance: Evaluating the Role of Green Finance. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Speed and Strategic Choice: How Managers Accelerate Decision Making. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1990, 32, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Cai, W. Banking Competition and Enterprise Growth: Empirical Evidence from Industrial Enterprises. Manag. World 2016, 31, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Ying, Q.; Yang, S.; Hassan, H. Trade Credit Financing and Sustainable Growth of Firms: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, W.R.; Nanda, R. Democratizing Entry: Banking Deregulations, Financing Constraints, and Entrepreneurship. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, D.; Sethi, P.; Bhattacharjee, S. Directed Credit, Financial Development and Financial Structure: Theory and Evidence. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 1711–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, B.; Schmid, L.; Steri, R. The Sources of Financing Constraints. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 139, 478–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, K.; Li, M.C. Corporate Investment Efficiency: The Role of Financial Development in Firms With Financing Constraints and Agency Issues in OECD Non-financial Firms. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2019, 62, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulatilaka, N.; Marcus, A.J. Project Valuation Under Uncertainty: When does DCF Fail? J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 1992, 5, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Zhang, B. Learning Actions, Control Actions and Firm’s Growth Option Value—An Evidence from China. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2007, 9, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kester, W.C. Today’s Options for Tomorrow’s growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1984, 62, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.-B.; Liu, J.; Bai, H.; Zhang, P. Value Assessment of Companies by Using an Enterprise Value Assessment System Based on Their Public Transfer Specification. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Q. The Effect of Economic Policy Uncertainty on Enterprise Total Factor Productivity Based on Financial Mismatch: Evidence from China. Pac. -Basin Financ. J. 2021, 68, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guriev, S. Soft Budget Constraints and State Capitalism. Acta Oeconomica 2018, 68, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.K. Slack in the State-owned Enterprise: An Evaluation of the Impact of Soft-budget Constraints. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 1998, 16, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, G.; Liu, L.-G. Honor Thy Creditors Beforan Thy Shareholders: Are the Profits of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises Real? Asian Econ. Pap. 2010, 9, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Yu, F. Financial Crisis, State Ownership and Capital Investment. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 49, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Xia, X.; Yu, M. Financial Development, Liquidity and Trade Credit: Evidences from China during the Global Financial Crisis. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2013, 16, 5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, F.; Shu, Z. The Inclusive Effects of Targeted RRR Cuts against the Background of Bank Competition: An Empirical Analysis Based on Corporate Data from Mainland China. J. Financ. Res. 2019, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, B. Source Identification and Dynamic Evolution of Regional Economic Growth Performance in China: Based on Input-level Decomposition. Econ. Res. J. 2015, 8, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, J.G. Regional Inequality and the Process of National Development: A Description of the Patterns. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1965, 13, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Nian, M.; Li, L. China’s Regional Development Strategy and Policy during the 14th Five-Year Plan Period. China Ind. Econ. 2020, 5, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Gao, T.; Zhu, F. China’s Regional Gap and Supply-side Structural Reform: Endogenous Growth in a Transition Period. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, G.; Glaeser, E.L.; Kerr, W.R. What Causes Industry Agglomeration? Evidence from Coagglomeration Patterns. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Mo, T. Index Futures Trading and Stock Market Volatility in China: A Difference-in-Difference Approach. J. Futures Mark. 2014, 34, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, R.N.D.; Duarte, G.; Silveira Neto, R.D.M.; Sampaio, B. Height Restrictions and Housing Prices: A Difference-in-discontinuity Approach. Econ. Lett. 2018, 164, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J.; Ichimura, H.; Smith, J.A.; Todd, P.E. Characterizing Selection Bias Using Experimental Data. NBER Work. 1998, 66, 1017–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waibel, S.; Petzold, K.; Rüger, H. Occupational Status Benefits of Studying Abroad and the Role of Occupational Specificity—A Propensity Score Matching Approach. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 74, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, G.B.; Trailer, J.W.; Hill, R.C. Measuring Performance in Entrepreneurship Research. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, P.N. The Nature and Role of IC. J. Intellect. Cap. 2003, 4, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, O.; Heggeseth, A.G.; Lome, O. The Positive Effect of Motivation and International Orientation on SME Growth. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 659–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmar, F.; Davidsson, P.; Gartner, W.B. Arriving at the High-growth Firm. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, O.; Cyrus, M.I.; Winnie, L.N. Corporate Governance, Capital Structure, Ownership Structure, And Corporate Value Of Companies Listed At The Nairobi Securities Exchange. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2021, 17, 300–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, S.; Forsman, H. Growth and Innovation during Economic Shocks: A Case Study for Characterising Growing Small Firms. Scand. J. Manag. 2022, 38, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brealey, R.A.; Myers, S.C. Principles of Corporate Finance; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.N.; Miller, N.H.; Petersen, M.A.; Rajan, R.G.; Stein, J.C. Does Function Follow Organizational Form? Evidence from the Lending Practices of Large and Small Banks. J. Financ. Econ. 2005, 76, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Du, B.; Wen, X. Mission Embeddedness and Pattern Selection of Digital Strategic Transformation of SOEs: A Case Study Based on the Typical Practice of Digitalization in Three Central Enterprises. Manag. World 2021, 37, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J. Speech at Private Enterprise Forum. Official Website of the Chinese Government. 2018. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-11/01/content_5336616.htm (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Sheng, L.; ZHeng, X.; Zhou, P.; Li, T. Analysis on the Reasons for the Widening Gap between North and South in China’s Economic Development. Manag. World 2018, 34, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Median | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | 1519 | 0.1351 | 0.0929 | 0.3514 | −0.9417 | 3.2350 |

| Value | 1519 | 4.1324 | 4.0478 | 0.8898 | 2.2579 | 8.6152 |

| PVGO | 1519 | 0.1662 | 0.3562 | 0.6743 | −4.1495 | 0.9526 |

| Size | 1519 | 3.6756 | 3.6034 | 0.9655 | 1.4889 | 7.1814 |

| Leverage | 1519 | 0.4151 | 0.4051 | 0.1914 | 0.0080 | 1.2019 |

| Return | 1519 | 0.0592 | 0.0638 | 0.1703 | −1.7311 | 2.1559 |

| Lage | 1519 | 2.9699 | 2.9957 | 0.2943 | 1.3863 | 3.7377 |

| Tax | 1519 | 0.1772 | 0.1619 | 0.2392 | −2.7114 | 6.0774 |

| GDP | 1519 | 0.0879 | 0.0892 | 0.0453 | −0.2796 | 0.2798 |

| Lrevenue | 1519 | 8.4390 | 8.5758 | 0.6463 | 5.3735 | 9.5542 |

| Variables | Before 2016 | After 2016 | MeanDiff | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | Mean | SD | Obs. | Mean | SD | |||

| Treatment | Growth | 304 | 0.0451 | 0.1833 | 456 | 0.1492 | 0.2854 | 0.1041 *** |

| Value | 304 | 3.9951 | 0.8496 | 456 | 4.4239 | 1.0368 | 0.4288 *** | |

| PVGO | 304 | 0.3495 | 0.4713 | 456 | 0.0801 | 0.7994 | −0.2694 *** | |

| Control | Growth | 304 | 0.2699 | 0.5039 | 456 | 0.0913 | 0.3458 | −0.1786 *** |

| Value | 304 | 3.8826 | 0.7750 | 456 | 4.0998 | 0.7403 | 0.2172 *** | |

| PVGO | 304 | 0.3431 | 0.4793 | 456 | 0.0121 | 0.7097 | −0.3310 *** | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | Value | PVGO | |

| Test × Policy | 0.2736 *** (0.0348) | 0.1444 *** (0.0358) | 0.0878 ** (0.0375) |

| Size | 0.0111 (0.0273) | 0.5794 *** (0.0281) | −0.3869 *** (0.0294) |

| Leverage | 0.1761 * (0.0904) | −0.7286 *** (0.0931) | −0.7053 *** (0.0974) |

| Return | 0.3276 *** (0.0597) | 0.3042 *** (0.0616) | 0.2558 *** (0.0644) |

| Lage | 0.0708 (0.2155) | 1.3582 *** (0.2220) | 1.3757 *** (0.2323) |

| Tax | −0.0316 (0.0397) | −0.0349 (0.0409) | −0.0978 * (0.0428) |

| GDP | −0.1889 (0.2571) | 0.2770 (0.2649) | 0.1706 (0.2772) |

| Lrevenue | −0.1312 (0.0742) | −0.1203 (0.0764) | 0.0092 (0.0800) |

| Constant | 0.8389 (0.8999) | −0.7929 (0.9272) | −2.3209 ** (0.9702) |

| Obs. | 1519 | 1519 | 1519 |

| R-squared | 0.2184 | 0.8706 | 0.7532 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | Value | PVGO | |

| Test × Policy × Debt | 0.1008 * (0.0100) | 0.0035 *** (0.0011) | 0.0053 *** (0.0011) |

| Debt | −0.0012 (0.0011) | −0.0031 *** (0.0012) | −0.0085 *** (0.0012) |

| Test × Policy | 0.2612 *** (0.0391) | 0.0830 ** (0.0402) | 0.0101 (0.0412) |

| Size | 0.0276 (0.0309) | 0.5962 *** (0.0317) | −0.2654 *** (0.0326) |

| Leverage | 0.2027 ** (0.0935) | −0.6689 *** (0.0960) | −0.5189 *** (0.0986) |

| Return | 0.3227 *** (0.0599) | 0.3061 *** (0.0616) | 0.2179 *** (0.0632) |

| Lage | 0.0360 (0.2177) | 1.3093 *** (0.2234) | 1.1232 *** (0.2294) |

| Tax | −0.0303 (0.0397) | −0.0343 (0.0407) | −0.0887 ** (0.0418) |

| GDP | −0.1916 (0.2572) | 0.2617 (0.2640) | 0.1544 (0.2711) |

| Lrevenue | −0.1317 * (0.0743) | −0.1301 * (0.0762) | 0.0082 (0.0783) |

| Constant | 0.8917 (0.9020) | −0.6082 (0.9259) | −1.9681 ** (0.9508) |

| Obs. | 1519 | 1519 | 1519 |

| R-squared | 0.2192 | 0.8717 | 0.7643 |

| Variables | State-Owned | Non-State-Owned | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Growth | Value | PVGO | Growth | Value | PVGO | |

| Test × Policy | 0.2636 *** (0.0490) | 0.0798 (0.0598) | −0.0037 (0.0645) | 0.2719 *** (0.0508) | 0.1987 *** (0.0455) | 0.1849 *** (0.0467) |

| Size | −0.0093 (0.0359) | 0.5393 *** (0.0438) | −0.3720 *** (0.0472) | 0.0170 (0.0408) | 0.6134 *** (0.0368) | −0.4085 *** (0.0378) |

| Leverage | 0.0812 (0.1293) | −0.7956 *** (0.1577) | −0.7787 *** (0.1701) | 0.2714 ** (0.1304) | −0.7902 *** (0.1177) | −0.7167 *** (0.1207) |

| Return | 0.4508 *** (0.1157) | 0.7073 *** (0.1411) | 0.4905 *** (0.1522) | 0.3130 *** (0.0737) | 0.1784 *** (0.0665) | 0.1920 *** (0.0682) |

| Lage | 0.0014 (0.3103) | 1.2169 *** (0.3783) | 0.9070 ** (0.4080) | 0.1396 (0.3030) | 1.4786 *** (0.2734) | 1.7933 *** (0.2805) |

| Tax | −0.0547 (0.0466) | 0.0056 (0.0569) | −0.0743 (0.0613) | −0.0035 (0.0661) | −0.0724 (0.0597) | −0.1298 ** (0.0612) |

| GDP | −0.3386 (0.3414) | 0.0841 (0.4163) | −0.0539 (0.4489) | −0.0409 (0.3762) | 0.3270 (0.3395) | 0.3073 (0.3483) |

| Lrevenue | −0.0714 (0.0817) | −0.2307 ** (0.0996) | −0.1347 (0.1074) | −0.2146 (0.1406) | 0.1048 (0.1269) | 0.2692 (0.1302) |

| Constant | 0.6246 (1.1547) | 0.7340 (1.4080) | 0.2703 (1.5184) | 1.3147 (1.5101) | −3.1747 ** (1.3626) | −5.7151 *** (1.3979) |

| Obs. | 640 | 640 | 640 | 879 | 879 | 879 |

| R-squared | 0.2274 | 0.8661 | 0.7726 | 0.2232 | 0.8769 | 0.7404 |

| Variables | Southern Region | Northern Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Growth | Value | PVGO | Growth | Value | PVGO | |

| Test × Policy | 0.2689 *** (0.0609) | 0.1282 *** (0.0410) | 0.0804 * (0.0446) | 0.3169 *** (0.0681) | 0.2475 *** (0.0777) | 0.1707 ** (0.0704) |

| Size | 0.0025 (0.0322) | 0.5772 *** (0.0322) | −0.4263 *** (0.0351) | 0.0554 (0.0530) | 0.5958 *** (0.0605) | −0.2719 *** (0.0548) |

| Leverage | 0.1810 * (0.1068) | −0.7940 *** (0.1069) | −0.7606 *** (0.1165) | 0.1992 (0.1781) | −0.5446 *** (0.2032) | −0.6874 *** (0.1841) |

| Return | 0.3197 *** (0.0673) | 0.2915 *** (0.0673) | 0.2864 *** (0.0733) | 0.3291 ** (0.1323) | 0.4047 *** (0.1509) | 0.2318 * (0.1368) |

| Lage | 0.1879 (0.2774) | 1.8176 *** (0.2778) | 1.8742 *** (0.3025) | −0.2451 (0.3374) | 0.4703 (0.3849) | 0.3969 (0.3489) |

| Tax | −0.0433 (0.0422) | −0.0299 (0.0422) | −0.0716 (0.0460) | 0.1351 (0.1286) | −0.1183 (0.1466) | −0.3595 *** (0.1329) |

| GDP | −0.1379 (0.4818) | 0.2952 (0.4824) | 0.2813 (0.5253) | 0.0658 (0.3415) | 0.3324 (0.3896) | 0.0909 (0.3531) |

| Lrevenue | −0.0554 (0.0989) | −0.0147 (0.0990) | 0.0682 (0.1078) | −0.3995 *** (0.1235) | −0.2824 ** (0.1409) | −0.0241 (0.1277) |

| Constant | −0.1045 (1.1641) | −3.0130 *** (1.1656) | −4.1579 *** (1.2692) | 3.6853 ** (1.4717) | 3.0089 ** (1.6788) | 0.4790 (1.5216) |

| Obs. | 1139 | 1139 | 1139 | 380 | 380 | 380 |

| R-squared | 0.2296 | 0.8664 | 0.7586 | 0.2444 | 0.8851 | 0.7569 |

| Regions | Growth | Value | PVGO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern region | 0.2689 | 0.1282 | 0.0804 |

| Northern region | 0.3169 | 0.2475 | 0.1707 |

| Chi-squared test statistics | 2.42 * | 2.44 * | 4.76 ** |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | Value | PVGO | |

| Test × Policy × North | 0.0361 * (0.0984) | 0.0439 * (0.0829) | 0.0777 * (0.0674) |

| North | −0.0134 (0.0256) | −0.0098 (0.0408) | 0.0107 (0.0333) |

| Test × Policy | 0.0360 * (0.0236) | 0.0831 ** (0.0402) | 0.0272 * (0.0391) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Q.; Zhang, Z. Do Financial Support Policies Catalyse the Development of New Consumption Field?—Evidence from China’s New Consumer Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013394

Lu Q, Zhang Z. Do Financial Support Policies Catalyse the Development of New Consumption Field?—Evidence from China’s New Consumer Enterprises. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013394

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Qin, and Zongyi Zhang. 2022. "Do Financial Support Policies Catalyse the Development of New Consumption Field?—Evidence from China’s New Consumer Enterprises" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013394

APA StyleLu, Q., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Do Financial Support Policies Catalyse the Development of New Consumption Field?—Evidence from China’s New Consumer Enterprises. Sustainability, 14(20), 13394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013394