Circular Fashion: Cluster Analysis to Define Advertising Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

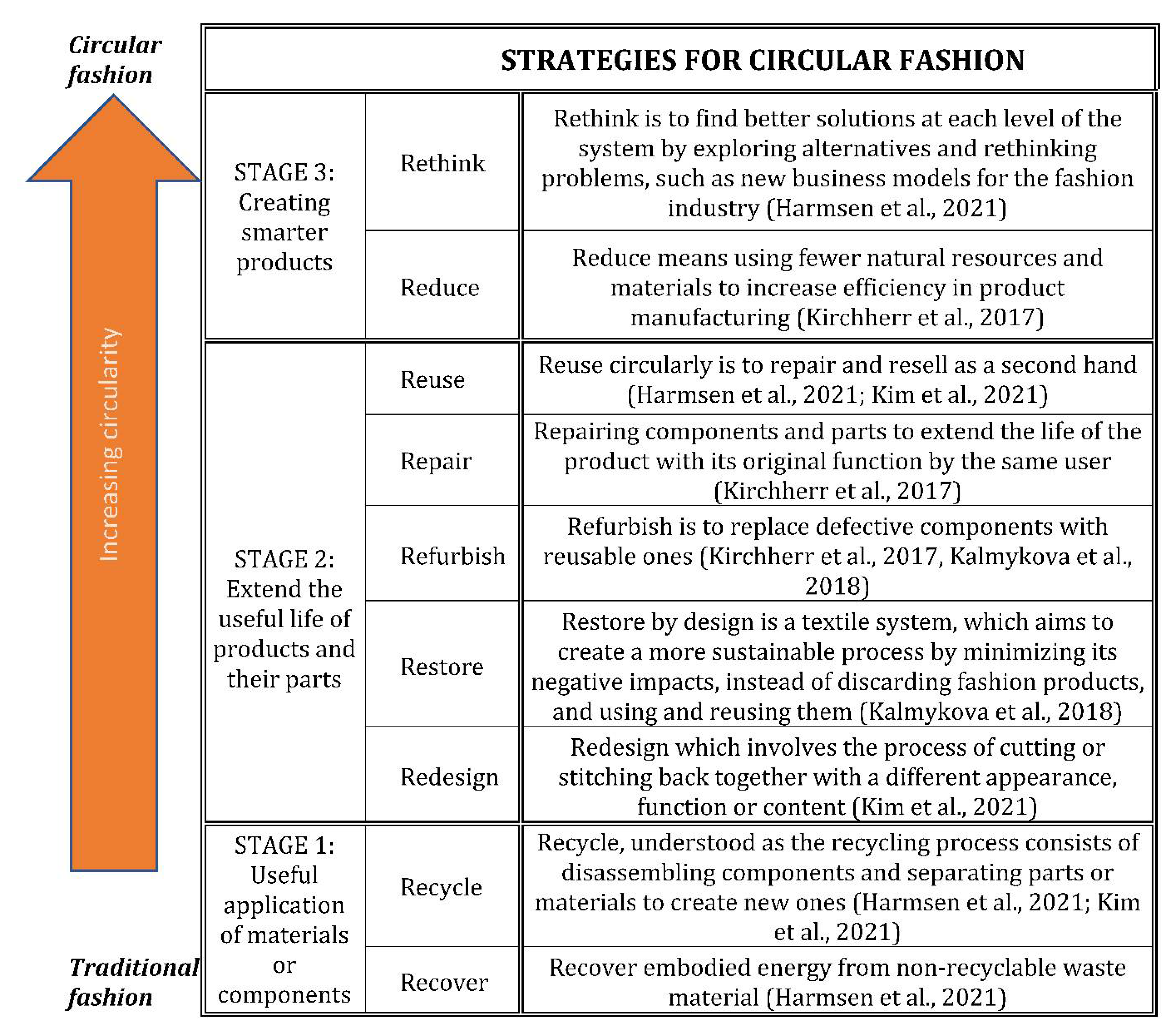

2.1. Principles of Circular Fashion–Awareness and Attitudes

2.2. Benefits of Circular Fashion to the Fashion Industry and Society

2.3. Enablers of Circular Fashion for Consumption

2.4. Gender, Age, and Budget in Circular Fashion Attitudes and Awareness

3. Material and Methodology

3.1. Sample

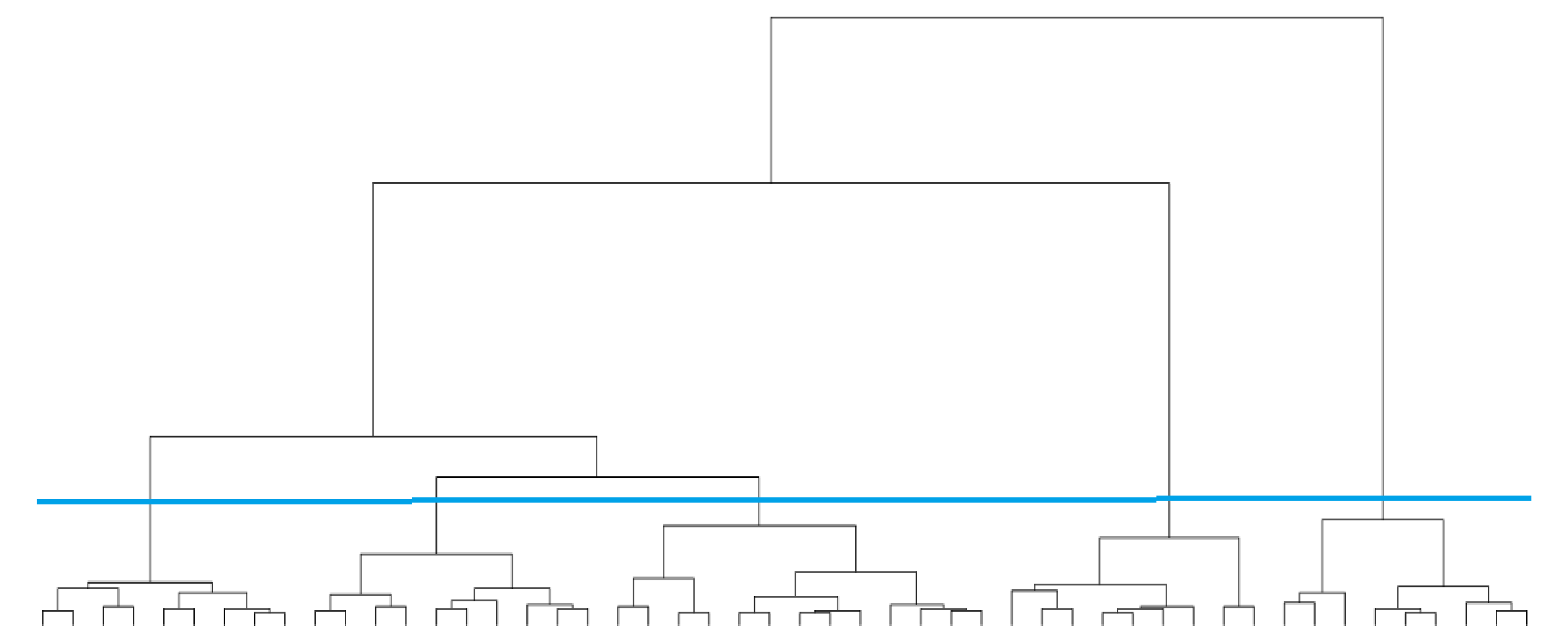

3.2. Empirical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Cluster 1. Circular Fashion Lovers

4.2. Cluster 2. Circular Fashion Followers

4.3. Cluster 3. Circular Fashion Laggards

4.4. Cluster 4. Starters to Leave Traditional Fashion

4.5. Cluster 5. True Believers in Traditional Fashion

4.6. Demographic and Personal Variables of Each Cluster

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questions | Likert-Type Scale Response Anchors |

|---|---|

| Do you know what circular fashion means? | a–Yes b–No |

| Are you aware of circular fashion as (include definition of circular fashion [2])? | Level of Awareness 1–Not aware 5–Very aware |

Are you aware of the basic circular fashion principles? (Here, explanation of Figure 1)

| Level of Awareness 1–Not aware 5–Very aware |

Are you aware of the benefits of circular fashion?

| Level of Awareness 1–Not aware 5–Very aware |

What would be important enablers for you when you are buying products created by circular fashion processes?

| Level of Agreement 1–Totally disagree 5–Totally agree |

Are you applying any circular fashion principles? (Here, explanation of Figure 1)

| Level of Agreement 1–Totally disagree 5–Totally agree |

Are you interested in purchasing traditional fashion products (make, use, dispose) or circular fashion products (reuse, repair, recycling, ….)?

| Level of Interest 1–Not interested 5–Very interested |

| Would you consider paying more for circular fashion products? | a–Yes b–No |

| After completing this questionnaire, do you think you have increased your knowledge about circular fashion? | a–Yes b–No |

Appendix B

| Cluster | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | F | Prob > F | |

| (n = 49) | (n = 65) | (n = 61) | (n = 37) | (n = 21) | |||

| Gender | 3.63 | ** | |||||

| Female | 79.6% | 53.8% | 59.0% | 51.4% | 38.1% | ||

| Male | 20.4% | 46.2% | 41.0% | 48.6% | 61.9% | ||

| Generation | 9.32 | *** | |||||

| Generation Z (1995–2010) | 49.0% | 78.5% | 80.3% | 91.9% | 95.2% | ||

| Millennials (1980–1994) | 10.2% | 4.6% | 3.3% | 8.1% | 0.0% | ||

| Generation X (1965–1979) | 22.4% | 13.8% | 9.8% | 0.0% | 4.8% | ||

| Baby Boomers (>1964) | 18.4% | 3.1% | 6.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Fashion budget per season | 0.56 | ||||||

| 50–200€ | 71.4% | 67.7% | 73.8% | 83.8% | 81.0% | ||

| 200–400€ | 24.5% | 32.3% | 19.7% | 10.8% | 19.0% | ||

| 400–700€ | 4.1% | 0.0% | 6.6% | 5.4% | 0.0% | ||

| Willingness to pay more | 0.44 | ||||||

| Yes | 75.5% | 69.2% | 78.7% | 70.3% | 71.4% | ||

| No | 24.5% | 30.8% | 21.3% | 29.7% | 28.6% | ||

| Initial knowledge of CF | 24.31 | *** | |||||

| Yes | 77.6% | 92.3% | 50.8% | 64.9% | 0.0% | ||

| No | 22.4% | 7.7% | 49.2% | 35.1% | 100.0% | ||

| Increase knowledge of CF | 2.66 | * | |||||

| Yes | 95.9% | 87.7% | 98.4% | 100.0% | 90.5% | ||

| No | 4.1% | 12.3% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 9.8% | ||

References

- de Ruyter, K.; Keeling, D.I.; Plangger, K.; Montecchi, M.; Scott, M.L.; Dahl, D.W. Reimagining marketing strategy: Driving the debate on grand challenges. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brismar, A. What Is Circular Fashion? Green Strategy. 2017. Available online: https://greenstrategy.se/circular-fashion-definition/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehmas, K.; Raudaskoski, A.; Heikkilä, P.; Harlin, A.; Mensonen, A. Consumer attitudes and communication in circular fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Fashion in a circular economy. In Sustainability in Fashion: A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Henninger, C.E., Alevizou, P.J., Goworek, H., Ryding, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Jain, S.; Malhotra, G. The anatomy of circular economy transition in the fashion industry. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 524–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G.; Afonso, C.; Gonçalves, H.M. Re-examining green purchase behaviour and the green consumer profile: New evidences. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Shrivastava, A.; Jain, G.; Kamble, S.S.; Belhadi, A. Sustainability through online renting clothing: Circular fashion fueled by Instagram micro-celebrities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.G.K.; Weerasinghe, D. Towards circular economy in fashion: Review of strategies, barriers and enablers. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 2, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A. Circular Economy: Measuring Innovation in the Product Chain. 2017. Available online: https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/pbl-2016-circular-economy-measuring-innovation-in-product-chains-2544.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Harmsen, P.; Scheffer, M.; Bos, H. Textiles for circular fashion: The logic behind recycling options. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular economy—From review of theories and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, Y. Consumers’ value and risk perceptions of circular fashion: Comparison between secondhand, upcycled, and recycled clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreth, M.R.; Ghosh, B. Competition and sustainability: The impact of consumer awareness. Decis. Sci. 2013, 44, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasante, A.; D’Adamo, I. The circular economy and bioeconomy in the fashion sector: Emergence of a “sustainability bias”. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Yin, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, X. The circular economy in the textile and apparel industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, M.; Vecchi, A. Close the loop: Evidence on the implementation of the circular economy from the Italian fashion industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 856–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandarić, D.; Hunjet, A.; Vuković, D. The impact of fashion brand sustainability on consumer purchasing decisions. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacometti, V. Circular economy and waste in the fashion industry. Laws 2019, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijkman, A.; Skånberg, K. The Circular Economy and Benefits for Society. Jobs and Climate Clear Winners in an Economy Based on Renewable Energy and Resource Efficiency. 2016. Available online: https://www.clubofrome.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/The-Circular-Economy-and-Benefits-for-Society.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Le Pechoux, B.; Little, T.J.; Istook, C.L. Innovation management in creating new fashions. In Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues; Hines, T., Bruce, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 136–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ræbild, U.; Bang, A.L. Rethinking the fashion collection as a design strategic tool in a circular economy. Des. J. 2017, 20, S589–S599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koszewska, M. Circular economy—Challenges for the textile and clothing industry. Autex Res. J. 2018, 4, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, M.; Gazzola, P.; Grechi, D.; Vătămănescu, E.M. Sustainable behaviour of B Corps fashion companies during Covid-19: A quantitative economic analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 134010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuc, S.; Tripa, S. Redesign and upcycling—A solution for the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises in the clothing industry. Ind. Text. 2018, 69, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchel, S.; Hebinck, A.; Lavanga, M.; Loorbach, D. Disrupting the status quo: A sustainability transitions analysis of the fashion system. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuc, S.; Gîrneatə, A.; Iordənescu, M.; Irinel, M. Environmental and socioeconomic sustainability through textile recycling. Ind. Textila 2015, 66, 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellieri, A.; Borboni, E.; Tenuta, L.; Testa, S. Circular economy in fashion world. In Proceedings of the International Conference Sharing Society, Bilbao, Spain, 23–24 May 2019; Tejerina, B., Miranda de Almeida, C., Perugorría, I., Eds.; pp. 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Ellams, D.; Han, S.; Tyler, D.; Boiten, V.J.; Paco, A.; Moora, H.; Balogun, A.L. A review of the socio-economic advantages of textile recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.-Y.; Wong, C.W.Y. The consumption side of sustainable fashion supply chain: Understanding fashion consumer eco-fashion consumption decision. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, T.; Cheng, R.; Grime, I. Fashion retailer desired and perceived identity. In Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues; Hines, T., Bruce, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, A.W.C.; Lam, M.C. Store environment of fashion retailers: A Hong Kong perspective. In Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues; Hines, T., Bruce, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.L.-C.; Henninger, C.E.; Blanco-Velo, J.; Apeagyei, P.; Tyler, D.J. The circular economy fashion communication canvas. In Proceedings of the Product Lifetimes and The Environment 2017—Conference Proceedings, Delft, The Netherlands, 30 November 2017; Bakker, C., Mugge, R., Eds.; pp. 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, C.; Armstrong, K.; Blazquez Cano, M. The epiphanic sustainable fast fashion epoch. In Sustainability in Fashion: A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Henninger, C.E., Alevizou, P.J., Goworek, H., Ryding, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tey, Y.S.; Brindal, M.; Dibba, H. Factors influencing willingness to pay for sustainable apparel: A literature review. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018, 9, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, V.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, R.; Gautam, A.; Sharma, V. Consumer adoption of green products: Modeling the enablers. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2013, 14, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, M.; Kyrdoda, Y.; Runfola, A. How do you depict sustainability? An analysis of images posted on Instagram by sustainable fashion companies. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.T. An examination of marketing techniques that influence millennials’ perceptions of whether a product is environmentally friendly. J. Strateg. Mark. 2010, 18, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.P.; Aldrich, C. Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Pinto, D.; Herter, M.M.; Rossi, P.; Borges, A. Going green for self or for others? Gender and identity salience effects on sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, R.D.; Roberts, J.A. Environmental segmentation alternatives: A look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.R.; Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R. Green issues: Dimensions of environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Bock, D.; Joseph, M. Green marketing: What the Millennials buy. J. Bus. Strategy 2013, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Watchravesringkan, K. (Tu) Who are sustainably minded apparel shoppers? An investigation to the influencing factors of sustainable apparel consumption. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punj, G.; Stewart, D.W. Cluster analysis in marketing research: Review and suggestions for application. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 20, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.C.; Moreira, S.B.; Dias, R.; Rodrigues, S.; Costa, B. Circular economy principles and their influence on attitudes to consume green products in the fashion industry. In Mapping, Managing, and Crafting Sustainable Business Strategies for the Circular Economy; Serrano Rodrigues, S., Almeida, P.J., Castaheira Almeida, N.M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 248–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lebart, L.; Morineau, A.; Lambert, T.; Pleuvret, P. Manuel de Référence de SPAD; Centre International de Statistique et d’Informatique Appliquées, CISIA-CERESTA: Montreuil, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nakache, J.-P.; Confais, J. Méthodes de Classification: Avec Illustrations SPAD et SAS; Centre International de Statistique et d’Informatique Appliquées, CISIA-CERESTA: Montreuil, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Escoffier, B.; Pagès, J. Analyses Factorielles Simples et Multiples: Objectifs, Méthodes et Interpretation; Dunod: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal, E.; Garcia Lautre, I.; Mallor, F. Data mining in a bicriteria clustering problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 173, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A further note on tests of significance in factor analysis. Br. J. Psychol. 1951, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, L.; Apetrei, A.; Pîslaru, M. Fast Fashion–An Industry at the Intersection of Green Marketing with Greenwashing. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium “Technical Textiles—Present and Future”, Iasi, Romania, 12 November 2021; pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg Mizrachi, M.; Tal, A. Regulation for Promoting Sustainable, Fair and Circular Fashion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.A.D.; Ordovás de Almeida, S.; Chiattone Bollick, L.; Bragagnolo, G. Second-hand fashion market: Consumer role in circular economy. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2019, 23, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddi, S.; Yan, R.-N. Consumer perceptions related to clothing repair and community mending events: A circular economy perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude—Behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.-W.W.; Park, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Toward a circular economy: Understanding consumers’ moral stance on corporations’ and individuals’ responsibilities in creating a circular fashion economy. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas Riesgo, S.; Lavanga, M.; Codina, M. Drivers and barriers for sustainable fashion consumption in Spain: A comparison between sustainable and non-sustainable consumers. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 58.80% |

| Male | 41.20% | |

| Generation | Generation Z (1995–2010) | 76.39% |

| Millennials (1980–1994) | 5.58% | |

| Generation X (1965–1979) | 11.59% | |

| Baby Boomers (>1964) | 6.44% | |

| Fashion budget per season | 50–200€ | 73.82% |

| 200–400€ | 22.75% | |

| 400–700€ | 3.43% | |

| Willingness to pay more for CF | Yes | 73.39% |

| No | 26.61% | |

| Initial knowledge of CF | Yes | 65.67% |

| No | 34.33% | |

| Increase knowledge of CF | Yes | 94.42% |

| No | 5.58% |

| Characteristic Variables | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Circular Fashion | 3.584 | 1.158 | |

| Purchase intention of Circular Fashion | 3.747 | 1.065 | |

| Purchase intention of Traditional Fashion | 3.043 | 1.022 | |

| Awareness of principles of Circular Fashion | |||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 3.279 | 1.199 |

| Reduce | 3.365 | 1.168 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 3.747 | 1.157 |

| Repair | 3.734 | 1.075 | |

| Refurbish | 3.712 | 1.107 | |

| Restore | 3.524 | 1.139 | |

| Redesign | 3.279 | 1.110 | |

| Useful application of materials or components | Recycle | 3.760 | 1.151 |

| Recover | 3.004 | 1.213 | |

| Attitudes to principles of Circular Fashion | |||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 2.927 | 1.218 |

| Reduce | 3.240 | 1.078 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 3.455 | 1.123 |

| Repair | 3.648 | 1.005 | |

| Refurbish | 3.515 | 1.069 | |

| Restore | 2.845 | 1.271 | |

| Redesign | 2.742 | 1.264 | |

| Useful application of materials | Recycle | 3.275 | 1.257 |

| Recover | 2.524 | 1.333 | |

| Benefits | |||

| Competitiveness | 3.532 | 1.176 | |

| Innovation | 3.665 | 1.123 | |

| Environment | 4.176 | 1.048 | |

| Employment | 3.343 | 1.097 | |

| Enablers | |||

| Marketing | 4.391 | 0.801 | |

| Placement | 3.949 | 0.961 | |

| Advertising | 4.219 | 0.823 | |

| Communication | 3.970 | 0.910 | |

| Social media | 4.451 | 0.858 | |

| Cluster No. | Name of Cluster | No. of Cases | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Circular Fashion Lovers | 49 | 21.03 |

| 2 | Circular Fashion Followers | 65 | 27.90 |

| 3 | Circular Fashion Laggards | 61 | 26.18 |

| 4 | Starters to Leave Traditional Fashion | 37 | 15.88 |

| 5 | True Believers in Traditional Fashion | 21 | 9.01 |

| Characteristic Variables | Cluster Mean | Cluster Std. Deviation | Test-Value | Probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Circular Fashion | 4.347 | 0.846 | 5.18 | 0.000 | |

| Purchase intention of Circular Fashion | 4.429 | 0.700 | 5.03 | 0.000 | |

| Awareness of principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 4.327 | 0.766 | 6.87 | 0.000 |

| Reduce | 4.306 | 0.676 | 6.33 | 0.000 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 4.673 | 0.511 | 6.29 | 0.000 |

| Repair | 4.469 | 0.703 | 5.38 | 0.000 | |

| Refurbish | 4.388 | 0.723 | 4.79 | 0.000 | |

| Restore | 4.408 | 0.636 | 6.11 | 0.000 | |

| Redesign | 4.143 | 0.833 | 6.12 | 0.000 | |

| Useful application of materials or components | Recycle | 4.612 | 0.664 | 5.82 | 0.000 |

| Recover | 3.816 | 1.024 | 5.26 | 0.000 | |

| Attitudes to principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 4.122 | 0.982 | 7.71 | 0.000 |

| Reduce | 4.224 | 0.763 | 7.18 | 0.000 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 4.245 | 0.821 | 5.53 | 0.000 |

| Repair | 4.265 | 0.722 | 4.83 | 0.000 | |

| Refurbish | 4.388 | 0.723 | 6.42 | 0.000 | |

| Restore | 4.041 | 1.068 | 7.39 | 0.000 | |

| Redesign | 4.102 | 0.863 | 8.45 | 0.000 | |

| Useful application of materials | Recycle | 4.408 | 0.780 | 7.09 | 0.000 |

| Recover | 3.592 | 1.211 | 6.30 | 0.000 | |

| Benefits | |||||

| Competitiveness | 4.469 | 0.610 | 6.27 | 0.000 | |

| Innovation | 4.531 | 0.610 | 6.06 | 0.000 | |

| Environment | 4.796 | 0.451 | 4.65 | 0.000 | |

| Employment | 4.245 | 0.770 | 6.46 | 0.000 | |

| Enablers | |||||

| Marketing | 4.673 | 0.549 | 2.78 | 0.0030 | |

| Placement | 4.551 | 0.672 | 4.93 | 0.0000 | |

| Advertising | 4.612 | 0.565 | 3.76 | 0.0000 | |

| Communication | 4.490 | 0.759 | 4.49 | 0.0000 | |

| Social media | 4.714 | 0.606 | 2.41 | 0.0080 | |

| Characteristic Variables | Cluster Mean | Cluster Std. Deviation | Test-Value | Probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Circular Fashion | 4.308 | 0.580 | 5.92 | 0.000 | |

| Awareness of principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 3.862 | 0.801 | 4.60 | 0.000 |

| Reduce | 3.969 | 0.822 | 4.90 | 0.000 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 4.262 | 0.750 | 4.21 | 0.000 |

| Repair | 4.338 | 0.615 | 5.33 | 0.000 | |

| Refurbish | 4.354 | 0.711 | 5.49 | 0.000 | |

| Restore | 4.046 | 0.753 | 4.35 | 0.000 | |

| Redesign | 3.615 | 0.817 | 2.87 | 0.002 | |

| Useful application of materials or components | Recycle | 4.231 | 0.855 | 3.88 | 0.000 |

| Recover | 3.400 | 1.107 | 3.09 | 0.001 | |

| Attitudes to principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Restore | 2.492 | 0.979 | −2.63 | 0.004 |

| Redesign | 2.369 | 0.970 | −2.80 | 0.003 | |

| Useful application of materials or components | Recover | 2.123 | 1.103 | −2.85 | 0.002 |

| Recycle | 2.846 | 1.126 | −3.23 | 0.001 | |

| Benefits | |||||

| Competitiveness | 4.000 | 0.894 | 3.77 | 0.000 | |

| Innovation | 4.185 | 0.762 | 4.38 | 0.000 | |

| Environment | 4.615 | 0.600 | 3.97 | 0.000 | |

| Characteristic Variables | Cluster Mean | Cluster Std. Deviation | Test-Value | Probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Circular Fashion | 3.033 | 0.868 | −4.31 | 0.000 | |

| Awareness of principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 2.902 | 0.804 | −2.86 | 0.002 |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 3.393 | 0.946 | −2.77 | 0.003 |

| Repair | 3.328 | 0.783 | −3.42 | 0.000 | |

| Refurbish | 3.410 | 0.755 | −2.48 | 0.007 | |

| Restore | 3.164 | 0.813 | −2.87 | 0.002 | |

| Useful application of materials | Recycle | 3.393 | 0.835 | −2.89 | 0.002 |

| Attitudes to principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Restore | 3.311 | 0.897 | 3.33 | 0.000 |

| Redesign | 3.131 | 0.932 | 2.79 | 0.003 | |

| Useful application of materials or components | Recycle | 3.033 | 1.201 | 3.46 | 0.000 |

| Recover | 3.344 | 0.866 | 3.11 | 0.001 | |

| Benefits | |||||

| Competitiveness | 3.115 | 0.812 | −3.22 | 0.001 | |

| Innovation | 3.131 | 0.858 | −4.31 | 0.000 | |

| Environment | 3.869 | 0.932 | −2.66 | 0.004 | |

| Enablers | |||||

| Marketing | 4.033 | 0.940 | −4.05 | 0.000 | |

| Placement | 3.590 | 1.014 | −3.38 | 0.000 | |

| Characteristic Variables | Cluster Mean | Cluster Std. Deviation | Test-Value | Probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 2.541 | 1.029 | −4.076 | 0.000 |

| Reduce | 2.703 | 0.801 | −3.751 | 0.000 | |

| Useful application of materials | Recycle | 2.514 | 1.056 | −2.677 | 0.004 |

| Attitudes to principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 1.622 | 0.748 | −7.092 | 0.000 |

| Reduce | 2.324 | 0.807 | −5.626 | 0.000 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 2.324 | 0.932 | −6.663 | 0.000 |

| Repair | 2.865 | 1.095 | −5.159 | 0.000 | |

| Refurbish | 2.405 | 1.026 | −6.870 | 0.000 | |

| Restore | 1.541 | 0.597 | −6.794 | 0.000 | |

| Redesign | 1.568 | 0.790 | −6.149 | 0.000 | |

| Useful application of materials or components | Recycle | 2.676 | 1.296 | −3.152 | 0.001 |

| Recover | 1.459 | 0.825 | −5.282 | 0.000 | |

| Enablers | |||||

| Communication | 3.622 | 0.911 | −2.534 | 0.006 | |

| Characteristic Variables | Cluster Mean | Cluster Std. Deviation | Test-Value | Probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Circular Fashion | 1.429 | 0.583 | −8.92 | 0.000 | |

| Purchase intention of Circular Fashion | 2.524 | 0.957 | −2.43 | 0.007 | |

| Awareness of principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 1.429 | 0.660 | −7.40 | 0.000 |

| Reduce | 1.333 | 0.563 | −8.34 | 0.000 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Reuse | 1.571 | 0.728 | −9.01 | 0.000 |

| Repair | 1.905 | 0.868 | −8.15 | 0.000 | |

| Refurbish | 1.714 | 0.881 | −8.65 | 0.000 | |

| Restore | 1.381 | 0.653 | −9.02 | 0.000 | |

| Redesign | 1.429 | 0.660 | −7.99 | 0.000 | |

| Useful application of materials | Recycle | 2.000 | 1.024 | −7.33 | 0.000 |

| Recover | 1.286 | 0.547 | −6.79 | 0.000 | |

| Attitudes to principles of Circular Fashion | |||||

| Creating smarter products | Rethink | 1.952 | 0.785 | −3.84 | 0.000 |

| Reduce | 2.476 | 0.852 | −3.40 | 0.000 | |

| Extend the useful life of products and their parts | Restore | 2.095 | 1.191 | −2.83 | 0.002 |

| Redesign | 1.667 | 0.836 | −4.08 | 0.000 | |

| Useful application of materials | Recover | 1.667 | 0.713 | −3.08 | 0.001 |

| Benefits | |||||

| Competitiveness | 1.476 | 0.663 | −8.38 | 0.000 | |

| Innovation | 1.857 | 1.082 | −7.72 | 0.000 | |

| Environment | 2.429 | 1.294 | −7.99 | 0.000 | |

| Employment | 1.667 | 0.836 | −7.33 | 0.000 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aramendia-Muneta, M.E.; Ollo-López, A.; Simón-Elorz, K. Circular Fashion: Cluster Analysis to Define Advertising Strategies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13365. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013365

Aramendia-Muneta ME, Ollo-López A, Simón-Elorz K. Circular Fashion: Cluster Analysis to Define Advertising Strategies. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13365. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013365

Chicago/Turabian StyleAramendia-Muneta, Maria Elena, Andrea Ollo-López, and Katrin Simón-Elorz. 2022. "Circular Fashion: Cluster Analysis to Define Advertising Strategies" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13365. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013365

APA StyleAramendia-Muneta, M. E., Ollo-López, A., & Simón-Elorz, K. (2022). Circular Fashion: Cluster Analysis to Define Advertising Strategies. Sustainability, 14(20), 13365. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013365