Balance between Hosts and Guests: The Key to Sustainable Tourism in a Heritage City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

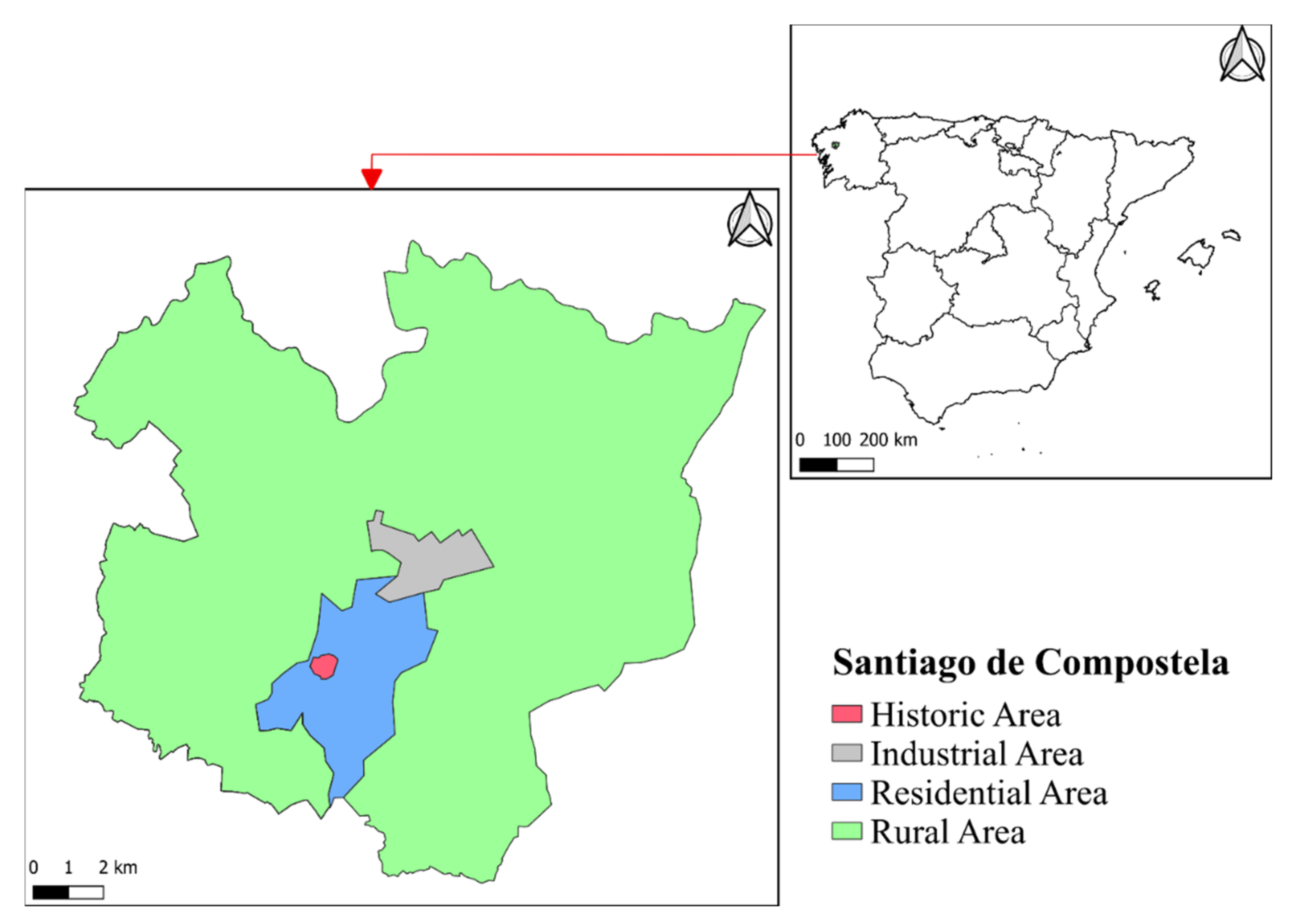

2.1. Case Study

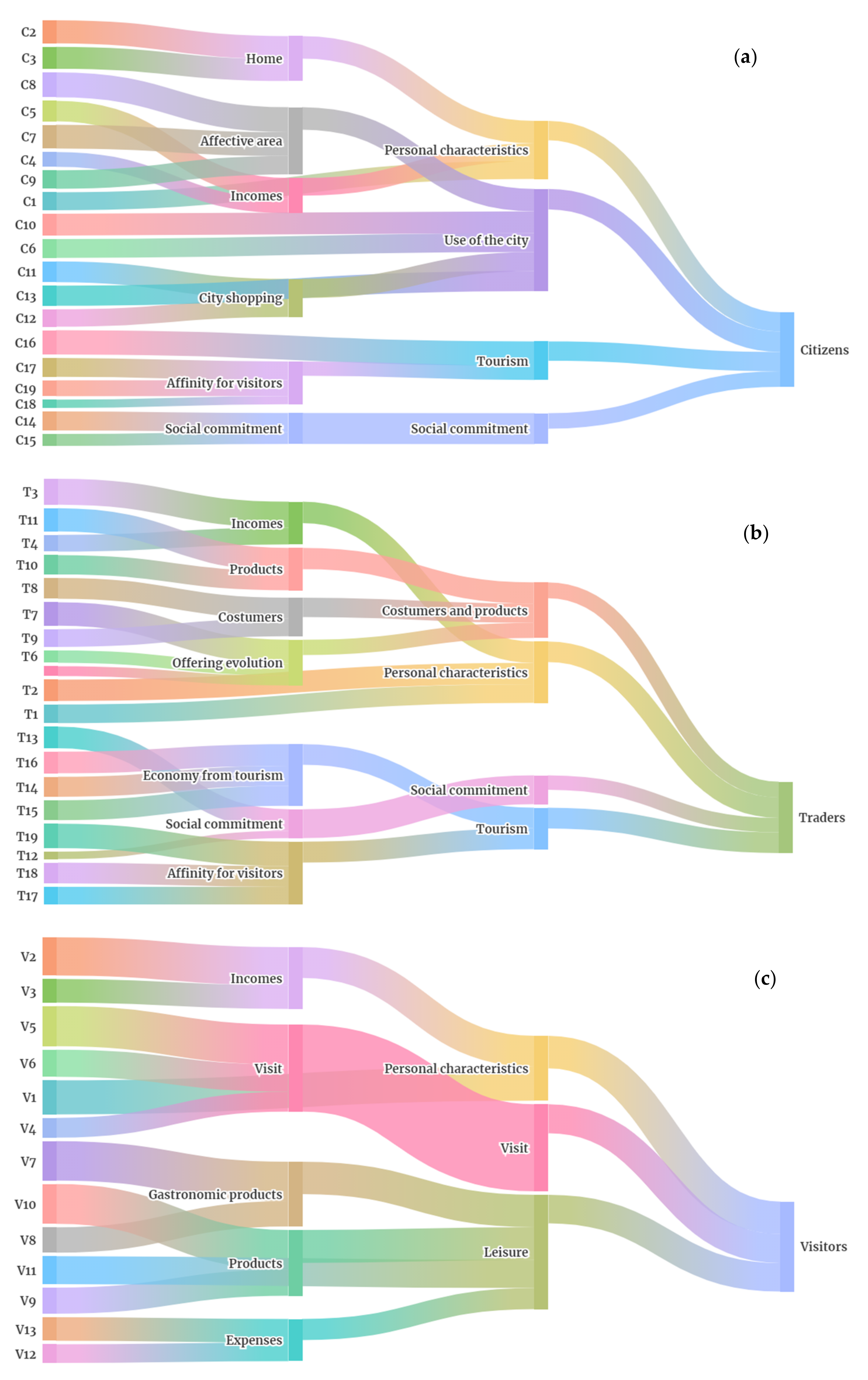

2.2. Indicators Selection

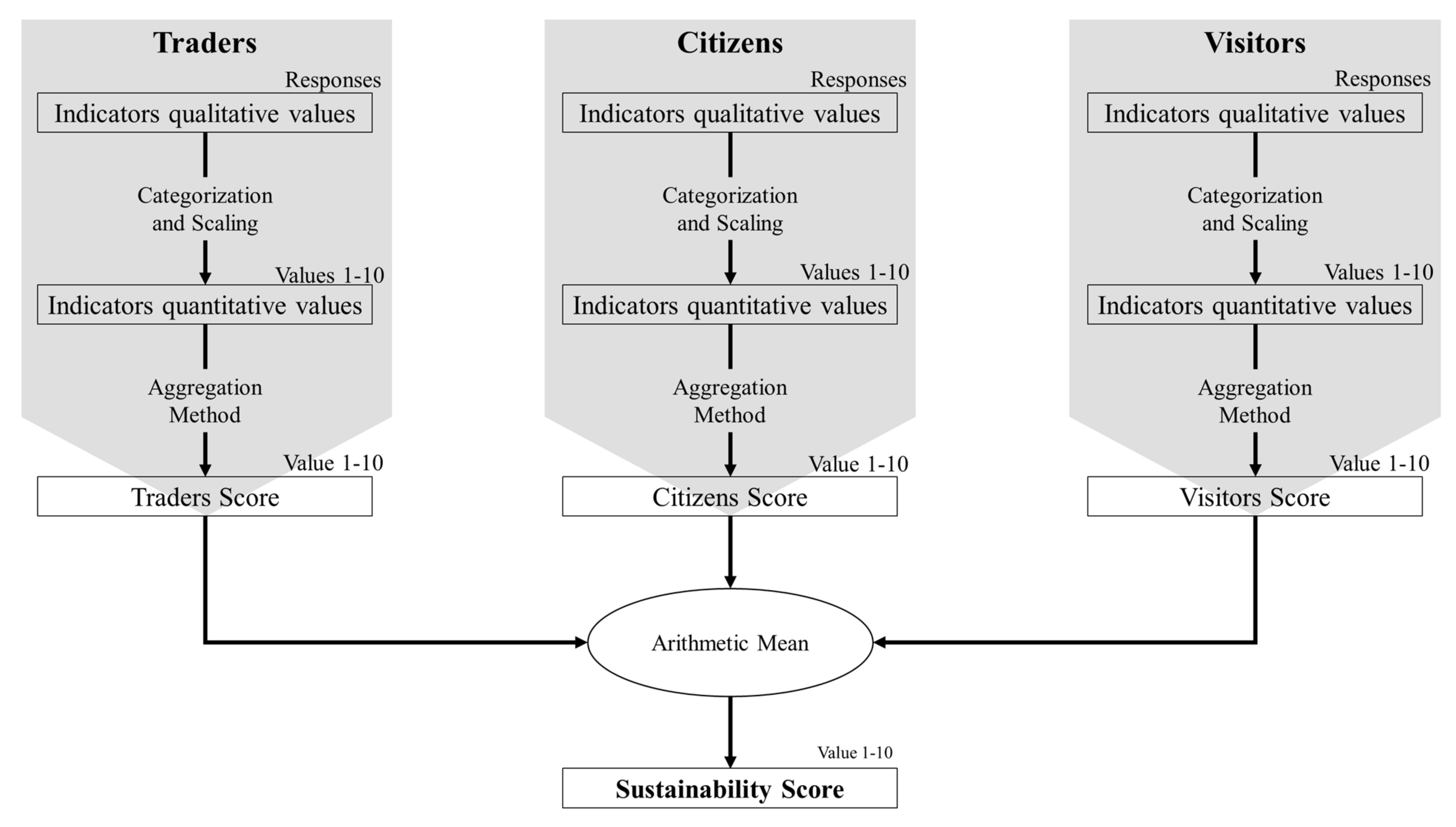

2.3. Sustainability Score Calculation

2.3.1. Categorization and Scaling of Indicators

2.3.2. Aggregation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Scaling and Categorization

3.1.1. Citizens

3.1.2. Traders

3.1.3. Visitors

3.2. Final Scores and Sustainability Score

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the anthropocene: The great acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysoulakis, N.; Lopes, M.; San José, R.; Grimmond, C.S.B.; Jones, M.B.; Magliulo, V.; Klostermann, J.E.M.; Synnefa, A.; Mitraka, Z.; Castro, E.A.; et al. Sustainable urban metabolism as a link between bio-physical sciences and urban planning: The BRIDGE project. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 112, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Marans, R.W. Quality of urban life & environmental sustainability studies: Future linkage opportunities. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, A.; Buda, D.M.; Gugerell, K. The future of city tourism. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE Data. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/industry/tourism-gdp.htm (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Biagi, B.; Ladu, M.G.; Meleddu, M.; Royuela, V. Tourism and the city: The impact on residents’ quality of life. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Pena, Z.; Samartim, R.; Bello Vázquez, R.; Pazos-Justo, C.; Iriarte Sanromán, Á.; Sotelo Docío, S. Visitar, Comerciar e Habitar a Cidade. Desenvolvemento do Proxecto Expositivo e Participación Social en Santiago de Compostela; Andavira: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Feijó, E.; del Rio Araujo, M.L.; Carral, E.V.; Rodríguez Prado, M.F.; Pichel Iglesias, I. A Cidade, o Camiño e nós. Desenvolvemento do Proxecto Expositivo e Participación Social en Santiago de Compostela; Andavira: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Claudio, M.; Joseph, M.C.; Marina, N. Overtourism: A Growing Global Problem. The Conversation España 2018. Available online: https://theconversation.com/overtourism-a-growing-global-problem-100029 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Trancoso González, A. Venice: The problem of overtourism and the impact of cruises. Investig. Reg. 2018, 42, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Parra, I.; Jover, J. Overtourism, place alienation and the right to the city: Insights from the historic centre of Seville, Spain. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.P.; Mundet, L. Tourism-phobia in Barcelona: Dismantling discursive strategies and power games in the construction of a sustainable tourist city. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 19(1), 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, S.; Gonella, F. ‘Kill Venice’: A systems thinking conceptualisation of urban life, economy, and resilience in tourist cities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, B.; Sanjuán, J. A measure of the economic dependence of countries on tourism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism and Business, Lucerne, Switzerland, 25–27 August 2022; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Moonga, M.S.; Namafe, C.; Chileshe, B. Sustainability model for integrating green concepts and practices into the curricula of tourism and hospitatily training institutions in Zambia. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2022, 6, 709–715. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Iglesias, R.; Fernandez-Feal, M.C.; Kennes, C.; Veiga, M.C. Valorization of agro-industrial wastes to produce volatile fatty acids: Combined effect of substrate/inoculum ratio and initial alkalinity. Environ. Technol. 2021, 42, 3889–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.M.; Chan, A.; Wu, J. A qualitative and quantitative assessment of Hong Kong’s image as a tourist destination. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgit, H.; Akanyeti, I. Environmental regulations versus sustainable tourism indicators: A pathway to sustainable development. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Lin, J.H. Evaluating ecotourism sustainability from the integrated perspective of resource, community and tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M. Using emotional solidarity to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism and tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2021, 51, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengesayi, S.; Mavondo, F.T.; Reisinger, Y. Tourism destination attractiveness: Attractions, facilities, and people as predictors. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Herrero, C.; Laso, J.; Cristóbal, J.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Albertí, J.; Fullana, M.; Herrero, A.; Margallo, M.; Aldaco, R. Tourism under a life cycle thinking approach: A review of perspectives and new challenges for the tourism sector in the last decades. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A. Tourists’ destination loyalty through emotional solidarity with redents: An integrative moderated mediation model. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Galician Institute of Statistics. Municipal Population Census. Statistical Exploitation. 1998–2021. Available online: http://www.ige.eu/web/mostrar_actividade_estatistica.jsp?idioma=gl&codigo=0201001002 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Galician Institute of Statistics. Municipal Gross Domestic Product. Statistical Review 2019. Available online: https://www.ige.eu/web/mostrar_actividade_estatistica.jsp?idioma=gl&codigo=0307007007 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Lopez, L.; Pazos Otón, M.; Piñeiro Antelo, M.A. Is there overtourism in Santiago de Compostela? Contributions for an ongoing debate. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2019, 83, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Galicia Institute of Statistics. Travelers, Nights and Average Stay in Hotel Establishments by Tourist Points-Municipalities. Monthly Data. Available online: http://www.ige.eu/web/mostrar_actividade_estatistica.jsp?codigo=0305002&idioma=es (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Rede Galabra. Impacts of the Camino on the Local Community of Santiago de Compostela. Available online: https://redegalabra.org/impactos-caminho-comunidade-local-santiago-compostela/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Tournois, L.; Rollero, C. “Should I stay or should I go?” Exploring the influence of individual factors on attachment, identity and commitment in a post-socialist city. Cities 2020, 102, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman, L. A basis for scaling qualitative data. Am. Sociol. 1944, 9, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleki, E.; Vlachokostas, C.; Moussiopoulos, N. Characterisation of sustainability in urban areas: An analysis of assessment tools with emphasis on European cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Guimarães, P. Public policy for sustainability and retail resilience in Lisbon city center. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Garrod, B.; Aall, C.; Hille, J.; Peeters, P. Food management in tourism: Reducing tourism’s carbon “foodprint". Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmohammadi, S.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Tambjerg, L.; Van Loon, P.; King, J.M.H.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. Comparative greenhouse gas footprinting of online versus traditional shopping for fast-moving consumer goods: A stochastic approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3499–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, M.; Saisana, M.; Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S.; Hoffman, A.; Giovannini, E. Handbook of Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, S. Determining a sustainable city model. Environ. Model. Softw. 2006, 21, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, S.; Rama, M.; Cortés, A.; García-Guaita, F.; Núñez, A.; Louro, L.G.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Embedding environmental, economic and social indicators in the evaluation of the sustainability of the municipalities of Galicia (northwest of Spain). J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Clifton, K.J. Local shopping as a strategy for reducing automobile travel. Transportation 2001, 28, 317–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carral, E.V.; Del Río, M.; López, Z. Gastronomy and tourism: Socioeconomic and territorial implications in Santiago de Compostela-galiza (NW Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P.; Spurr, R.; Hoque, S. Estimating the carbon footprint of Australian tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Martínez-Blanco, J.; Montlleó, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Tavares, N.; Arias, A.; Oliver-Solà, J. Carbon footprint of tourism in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, H.; Grundius, J.; Heinonen, J. Carbon footprint of inbound tourism to Iceland: A consumption-based life-cycle assessment including direct and indirect emissions. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. The Carbon Footprint of Domestic Tourism; LEaP Research Centre: Wellington, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Cod. | Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Citizens | ||

| C1 | Level of education | Educational level of citizens |

| C2 | Municipality of residence | Residence in the city, in the metropolitan area or in a more distant location |

| C3 | Residence within the city | How far from the city center you live |

| C4 | Family income level | Household income level according to high or low income |

| C5 | Employment Situation | Employment situation: Worker, unemployed, student, etc. |

| C6 | Leisure places | Areas frequented during leisure time |

| C7 | Affective areas | Places that have affection for citizens |

| C8 | Coincidence in significant places | Citizen’s perception of the coincidence of the most affective areas |

| C9 | Alternative tourist elements | Citizens believe if there are elements that should be part of the image of the city |

| C10 | City use time | Years that a citizen has been using the city daily |

| C11 | Shopping establishments | Types of favorite establishments |

| C12 | Shopping Site | Place where purchases are made with respect to the district of residence |

| C13 | Use of the historic area | Part of the daily life of the citizens takes place in the historic area |

| C14 | Place attachment | How a citizen perceives his/her belonging to the city |

| C15 | Community participation | Participate actively within the community (Neighborhood Association, municipal policy, charity, etc.) |

| C16 | Economic dependence on tourism | Degree of economic dependence on tourism |

| C17 | Tourist image of the city | How much is in accordance with the image of the city |

| C18 | Citizen lifestyle | How much tourism affects the way of life of citizens |

| C19 | City evolution | Opinion on whether citizens prefer the city in the early 1990s, when there were few tourists, or today |

| Traders | ||

| T1 | Level of education | Educational level of traders |

| T2 | Municipality of residence | Residence in the city, in the metropolitan area or in a more distant location |

| T3 | Employment situation | Employment situation: Worker, unemployed, student, etc. |

| T4 | Family income level | Household income level according to high or low income |

| T5 | Offering evolution | Whether or not the commercial and economic offer improved with the increase in tourism |

| T6 | Perception of changes in the offer | How much the offer changes due to tourism |

| T7 | Perception of changes in the offer (other establishments) | How much the offer changes due to tourism in other establishments |

| T8 | Customers in the early 1990s | Type of customers that frequented the business in the early 1990s |

| T9 | Customers at present | Type of customers that frequented the business at present |

| T10 | Difference in most demanded products | Visitors and citizens do or do not consume different types of products |

| T11 | Evolution in most demanded products | The most demanded products changed with the increase in tourism or not |

| T12 | Community participation | Participate actively within the community (Neighborhood Association, municipal policy, charity, etc.) |

| T13 | Place attachment | How a trader identifies who belongs to the city |

| T14 | Income from tourism | Percentage of income from tourism at present |

| T15 | Income from tourism (early 1990s) | Percentage of income from tourism in the early 1990s |

| T16 | Economic dependence on tourism | Degree of economic dependence on tourism |

| T17 | Tourist image of the city | How much is in accordance with the image of the city |

| T18 | Type of visitor | How much do you like the type of visitor who comes to city |

| T19 | Camino de Santiago as Public Image | How much is the Camino de Santiago part of the identity of the city |

| Visitors | ||

| V1 | Level of education | Educational level of visitors |

| V2 | Employment Situation | Employment situation: Worker, unemployed, student, etc. |

| V3 | Family income level | Household income level according to high or low income |

| V4 | Transport used | Means of transport used |

| V5 | Satisfaction with the visit | How satisfied are you with the visit? |

| V6 | Discovered activities | Activities and places that surprised the visit |

| V7 | Places to plan to eat and drink | Places where visitors eat and drink |

| V8 | Expenditures on food products | Consumption of local gastronomic products |

| V9 | Shopping in the city | Do visitors make purchases? |

| V10 | Shopping places | Places where visitors shopping |

| V11 | Accommodation in the city | Visitors stay in or out of town |

| V12 | Spending on visit | Spending on leisure and transport/ accommodation |

| V13 | Total spending per person | Total spending per person on the trip |

| Number of Categories | Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 | Category 5 | Category 6 | Category 7 | Category 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1.0 | 10.0 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.0 | 5.5 | 10.0 | |||||

| 4 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | ||||

| 5 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 10.0 | |||

| 6 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 6.4 | 8.2 | 10.0 | ||

| 7 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 8.5 | 10.0 | |

| 8 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 7.4 | 9.7 | 10.0 |

| Level 1 Composite Indicators | Level 2 Composite Indicators |

|---|---|

| Citizens | |

| Home | Personal Characteristics |

| Incomes | |

| Affective area | Use of the city |

| City Shopping | |

| Social Commitment | |

| Affinity for visitors | Tourism |

| Traders | |

| Incomes | Personal Characteristics |

| Offering evolution | Customers and products |

| Customers | |

| Products | |

| Social Commitment | |

| Economy from tourism | Tourism |

| Affinity for visitors | |

| Visitors | |

| Incomes | Personal Characteristics |

| Visit | |

| Gastronomic products | Leisure |

| Products | |

| Expenses | |

| Indicator | Nº Categories | Categories | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Score Categories | High Score Categories | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Citizens | |||||||||

| C1 | 3 | No education or primary education | Secondary Education | University Education | |||||

| C2 | 3 | Others | Ames-Teo | Santiago de Compostela | |||||

| C3 | 5 | Most far | Far | Medium Distance | Near | City center | |||

| C4 | 2 | Low | High | ||||||

| C5 | 4 | Unemployed | Students | Pensioners | Workers | ||||

| C6 | 7 | Any area alike | Sport and cultural area | Restoration | Residential area | Green areas | Historic area | Cathedral | |

| C7 | 5 | Industrial area | Residential area | Bar, pubs and leisure | Green areas | Historic area | |||

| C8 | 2 | No | Yes | ||||||

| C9 | 2 | No | Yes | ||||||

| C10 | 5 | Less than 2 years | 2–5 years | 6–10 years | 11–20 years | More than 20 years | |||

| C11 | 3 | Shopping Center | Hypermarket or Supermarket | Market and traditional shop | |||||

| Citizens | |||||||||

| C12 | 3 | Other districts | Other districts and in the district | In the district | |||||

| C13 | 2 | No | Yes | ||||||

| C14 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| C15 | 2 | No participation | Participation | ||||||

| C16 | 3 | Total dependence | Partial dependence | Non dependence | |||||

| C17 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| C18 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| C19 | 3 | Early 90’s | Early 90’s and at present | At present | |||||

| Traders | |||||||||

| T1 | 3 | No education or primary education | Secondary Education | University Education | |||||

| T2 | 3 | Others | Ames-Teo | Santiago de Compostela | |||||

| T3 | 4 | Unemployed | Students | Pensioners | Workers | ||||

| T4 | 2 | Low | High | ||||||

| T5 | 3 | Early 90’s | Early 90’s and at present | At present | |||||

| T6 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| T7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| T8 | 3 | Mostly visitors | Mix of visitors and citizens | Mostly citizens | |||||

| T9 | 3 | Mostly visitors | Mix of visitors and citizens | Mostly citizens | |||||

| T10 | 2 | Yes | No | ||||||

| T11 | 2 | Yes | No | ||||||

| T12 | 2 | No participation | Participation | ||||||

| T13 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| T14 | 3 | High | Medium | Low | |||||

| T15 | 3 | High | Medium | Low | |||||

| T16 | 3 | Total dependence | Partial dependence | Non dependence | |||||

| T17 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| T18 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| T19 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Visitors | |||||||||

| V1 | 3 | No education or primary education | Secondary Education | University Education | |||||

| V2 | 4 | Unemployed | Students | Pensioners | Workers | ||||

| V3 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| V4 | 5 | Plane | Car | Bus | Train | Walk/Bike | |||

| V5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| V6 | 3 | Cathedral | City/City Size | Other | |||||

| V7 | 3 | Fast food chains | Hotels, Hospital canteens | Local restaurants | |||||

| V8 | 3 | Fast food | Other | Traditional food | |||||

| V9 | 2 | No | Yes | ||||||

| V10 | 3 | Shopping center | Residential area | Historic area street markets | |||||

| V11 | 2 | No | Yes | ||||||

| V12 | 2 | Travel expenses | Leisure expenses | ||||||

| V13 | 5 | 0–99 € | 100–332 € | 333–665 € | 66–1099 € | >1100 € | |||

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Citizens | 6.95 |

| Trader | 6.88 |

| Visitors | 6.69 |

| Santiago de Compostela | 6.84 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rama, M.; Carral, E.; González-García, S.; Torres-Feijó, E.; del Rio, M.L.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Balance between Hosts and Guests: The Key to Sustainable Tourism in a Heritage City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013253

Rama M, Carral E, González-García S, Torres-Feijó E, del Rio ML, Moreira MT, Feijoo G. Balance between Hosts and Guests: The Key to Sustainable Tourism in a Heritage City. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013253

Chicago/Turabian StyleRama, Manuel, Emilio Carral, Sara González-García, Elías Torres-Feijó, Maria Luisa del Rio, María Teresa Moreira, and Gumersindo Feijoo. 2022. "Balance between Hosts and Guests: The Key to Sustainable Tourism in a Heritage City" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013253

APA StyleRama, M., Carral, E., González-García, S., Torres-Feijó, E., del Rio, M. L., Moreira, M. T., & Feijoo, G. (2022). Balance between Hosts and Guests: The Key to Sustainable Tourism in a Heritage City. Sustainability, 14(20), 13253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013253