Factors Influencing the Willingness to Pay in Yachting Tourism in the Context of COVID-19 Regular Prevention and Control: The Case of Dalian, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Yachting Tourism

2.2. Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

2.3. Willingness to Pay (WTP)

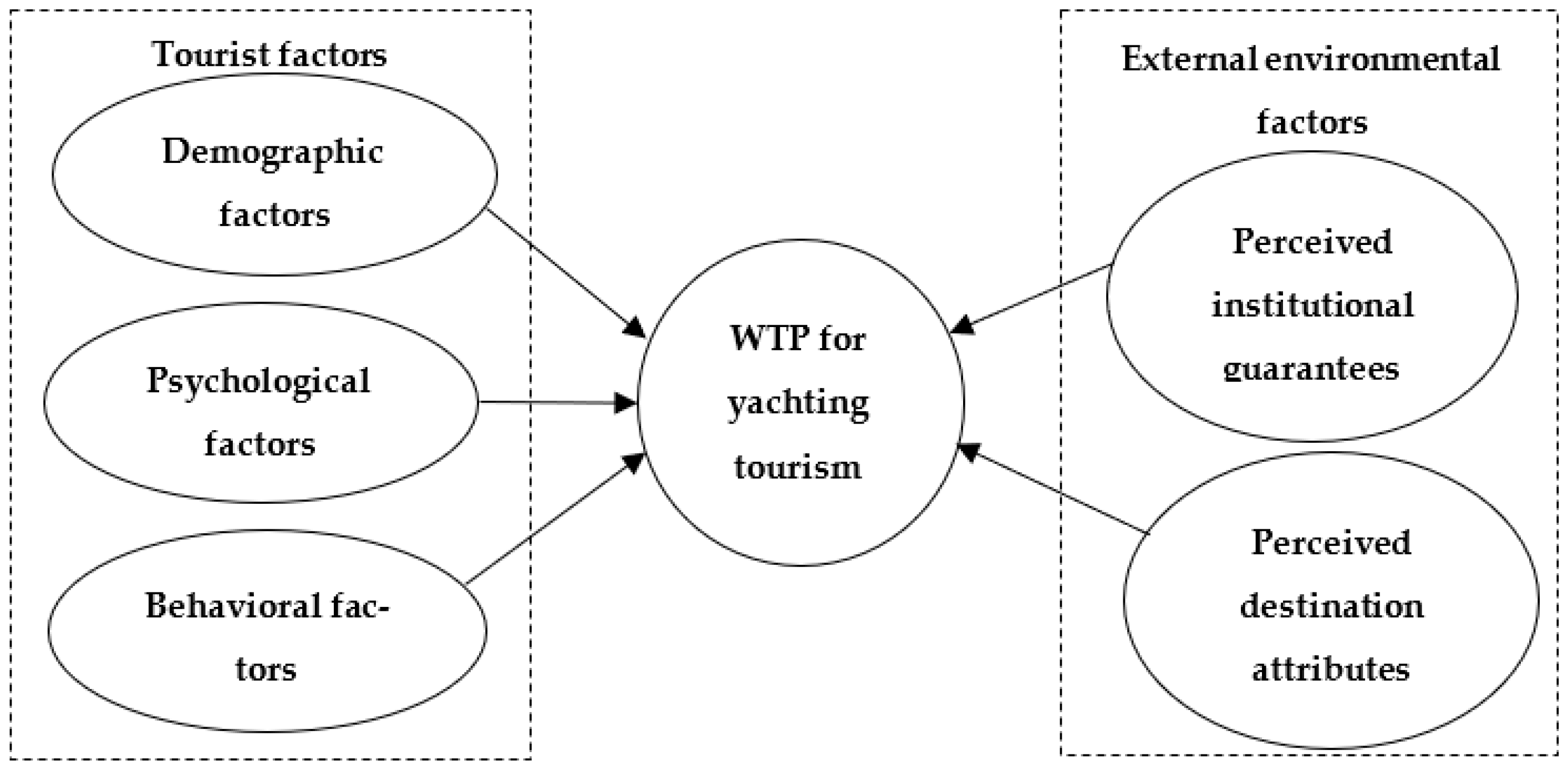

2.4. Theoretical Model and Research Hypotheses

3. Research Design

3.1. Measures

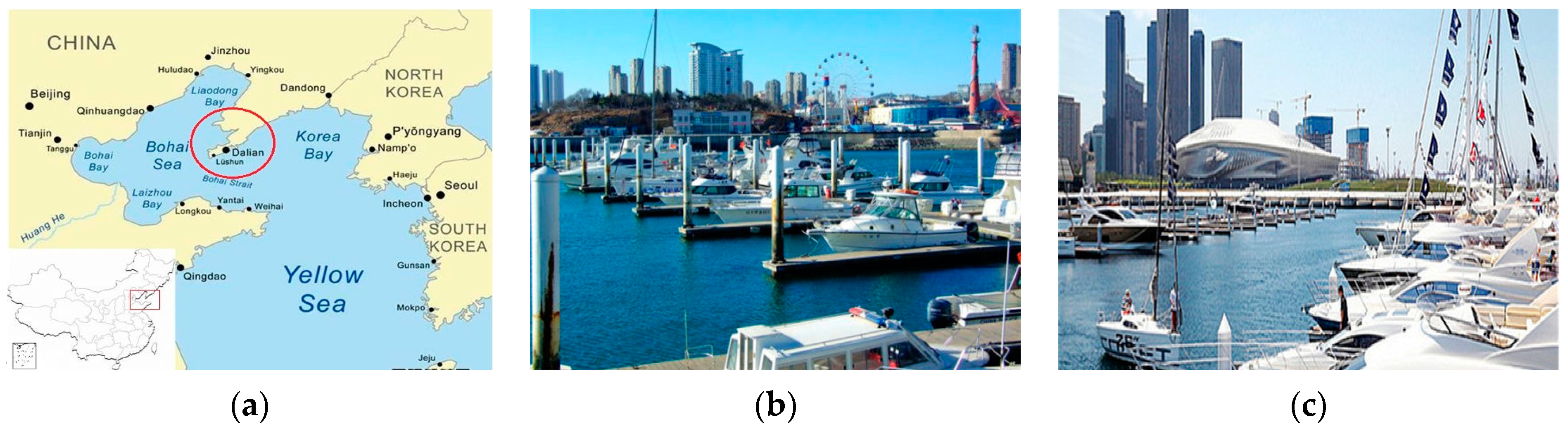

3.2. Data Source

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Test

4.3. Result and Discussion

- (1)

- Demographic factors. Firstly, for the overall sample, education (β = 0.356, p < 0.05) and income (β = 0.420, p < 0.01) both had significant positive correlations with the WTP, and thus, H1 is partially supported. The continuous improvement of people’s economic and educational level would be conducive to the popularization of yachting tourism [76]. For tourists who prefer motor boats, age (β = 0.463, p < 0.1) and income (β = 0.651, p < 0.01) are significantly positively correlated with the WTP, the price of motor boat rental experience is relatively high, and consumer demand will increase with age and income. In contrast, the consumption threshold of non-motor boats is relatively low, and the offshore is close and relatively safe, so there is no significant relationship with the age and income of tourists. In addition, married families with minor children have a greater impact on the WTP for motor boats than married families with adult children (β = 1.200). Since most married families with minor children are in the stage of strong purchasing power, physical quality, and learning ability, their consumption for yachting tourism is higher, which is also consistent with the research results of Sherman et al. [54].

- (2)

- Psychological factors. First, there is a significant positive correlation between the attitude and the WTP for yachting tourism. The β values of the three models are 0.302 (p < 0.01), 0.245 (p < 0.05), and 0.318 (p < 0.01) respectively. Hence, H2 is partially supported. If individuals believe that yachting tourism is the embodiment of life interest and are interested in it, the probability of participating and the amount of expenditure would be greater. Secondly, there is a significant positive correlation between perceived behavior control and the WTP (β = 0.125). The influence of perceived behavioral control on WTP depends on individual control and perceived belief [12]. If individuals think their physical condition or ability is better, their control belief will be stronger, and they may participate more deeply in yachting under the normalized situation of COVID-19. If individuals perceive that they have more money, time, and other resources, the convenience of participating in yachting tourism will be stronger, and then the WTP for yachting tourism will be higher. However, values and subjective norms have no significant impact on the WTP. There may be no connection between values and tourist behavior, or the tourists are not aware of the relationship, or what the exact meaning is [77,78]. Yachting tourism consumption decisions are relatively independent, as yachting tourism has a limited following and belongs to a niche market; and people tended to travel in smaller groups and become more responsible tourists during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- (3)

- Behavioral factors. Past consumption experience has a positive correlation with the WTP for yachting tourism (β = 0.345, p < 0.01). Especially for the tourists who prefer non-motor boats (β = 0.627, p < 0.01), past yachting tourism behavior can reduce time, costs, and selection risks of consumers, and has a significant impact on future yachting behavior. Similar to Bagozzi and Kimmel’s study, past behavior had a direct impact on intentions and subsequent behavior [58]. In contrast, due to the relatively high personal income of people who prefer motor boats, past consumption experience and other factors have no significant impact on them. They have enough economic capacity to maintain a high frequency of yachting experience. This high frequency of consumption behavior is not highly correlated with good feelings associated with past consumption experience.

- (4)

- Perceived institutional factors. Perceived institutional factors were generally not significant for the WTP for yachting tourism. This result may be related to the current situation in which epidemic prevention and control is becoming routine and consumption in the domestic tourism market is steadily opening up and growing. With the liberalization of China’s domestic tourism, the resumption of flights for inbound and outbound tourism, as well as favorable policies and measures such as “vaccine passports” and non-quarantine entry, China’s tourism market is steadily recovering, and “reservation, limit, and off-peak” has become a new tourism rule [79]. The Chinese government’s strict epidemic prevention policy has, in a sense, guaranteed the consumption of yachting tourism. However, for tourists who preferred non-motor boats, perceived institutional guarantees had a significant positive correlation with the WTP (β = 0.112, p < 0.05). As consumers who prefer non-motor boats sail mainly close to the coast and in relatively densely populated areas, they are also more sensitive to epidemic prevention measures (e.g., reporting personal information, monitoring body temperature, and social distancing). The sounder the social security, yacht safety management, and epidemic prevention and control systems, the more the worries of consumers are reduced and their WTP stimulated [80].

- (5)

- Perceived destination attribute factors. There were significant positive correlations between the core attributes of destination and the WTP, with the β values of the three models being 0.182 (p < 0.01), 0.287 (p < 0.01), and 0.161 (p < 0.01), respectively. Hence, H5 is partially supported. The more beautiful the destination, the richer the onshore activities, the more complete the marina basic service facilities, and the more developed the tourism transportation are, the more consumers are willing to purchase yachting tourism services. As far as the degree of influence is concerned, the core attributes had a greater impact on consumers who preferred motor boats. The reason concerns high fuel consumption, and high maintenance, berthing and labor costs. Sailing distances are also relatively far from the mainland coastline, and motor boats users have higher demands for natural scenery on the route, marina facilities, and shore transportation. Users have greater demand and higher requirements for core attributes, and they are willing to pay higher prices for them [54]. In addition, perceived destination peripheral attributes have no significant impacts on the WTP. This may be because local yacht clubs or sea cruise companies could provide safe and high-quality services, as well as a socially secure environment, reducing consumers’ sensitivity to peripheral attributes.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Tourism Academy (CTA). “The Annual Report on The Development of China’s Domestic Tourism 2021” Released—The Beginning of the 14th Five-Year Plan, Marking a New Stage of High-Quality Development for Domestic Tourism. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1714035058988948225&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- CCTV News Client. Accelerate the Restoration of Production and Life Order under the Conditions of Normalization of Epidemic Prevention and Control [EB/OL]. Available online: http://www.ce.cn/xwzx/gnsz/gdxw/202003/28/t20200328_34572148.shtml (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- China Cruise and Yacht Industry Association (CCYIA). China Yacht Industry Report in 2019–2020; China Cruise & Yacht Industry Association: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMIA (International Council of Marine Industries Association). Recreational Boating Industry Statistics 2019. 2020. Available online: http://www.icomia.org (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- China Cruise and Yacht Industry Association (CCYIA). National Expert Committee on Yacht Development. Trends of Chinese Yacht Industry; Internal Report; China Cruise and Yacht Industry Association (CCYIA): Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dalian Release. “Dalian Summer Tour” is on Fire! Data Release! Available online: http://mp.weixin.qq/s/peZxxk-WATLf_aY2hooj6g (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Fu, G.C.; Chen, X.H. Analysis on safety management practice of yacht leasing and associated countermeasures. China Marit. Saf. 2022, 09, 38–39, 43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Shi, Q.; Chen, W.X. Perception and attraction of yachting tourism from the Chinese tourist. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 218–224. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research Reading; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Crina, P.D.; Florina, B. The use of smartphone for the search of touristic information: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. Acad. Econ. Stud. 2020, 54, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Han, H. Investigating individual’ decision formation in working-holiday tourism: The role of sensation-seeking and gender. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.L. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict outbound tourists’ civilization tourism in behavioral intention. Tourism Tribune 2017, 6, 75–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. Extending the theory of planned behaviour: Testing the effects of authentic perception and environmental concerns on the slow-tourist decision-making process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shi, X.Q. Research on the impact mechanism of sports tourism consumption behavior under the background of the normalization of COVID-19 prevention and control: Empirical analysis of MOA-TAM integration model based on S-O-R framework. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 52–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. Spatial and experimental analysis of peer-to-peer accommodation consumption during COVID-19. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchetchik, A.; Kaplan, S.; Blass, V. Recycling and consumption reduction following the covid-19 lockdown: The effect of threat and coping appraisal, past behavior and information. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Methodological Manual for Tourism Statistics. Version 3.1, 2014th ed.; European Union: Luxembourg, 2015.

- Jafari, J. Encyclopedia of Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alcover Casasnovas, A. Yachting Tourism. Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1033–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Luković, T. Nautical tourism-definition and dilemmas. Naše More Znan. Časopis Za More I Pomor. 2007, 54, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.H.; Liu, Y.X.; Huang, L. Motivation-based segmentation of yachting tourists in China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Feng, X.; Gauri, D.K. The cruise industry in China: Efforts, progress and challenges. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paker, N.; Vural, C.A. Customer segmentation for marinas: Evaluating marinas as destinations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariisik, M.; Turkay, O.; Akova, O. How to manage yacht tourism in Turkey: A swot analysis and related strategies. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Balomenou, C.K.; Nijkamp, P.; Poulaki, P. The sustainability of yachting tourism: A case study in Greece. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 2, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakomihalis, M.N.; Lagos, D.G. Estimation of the economic impacts of yachting in Greece via the tourism satellite account. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C. Determinants of recreational boater expenditures on trips. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L. Leisure constraints: A survey of past research. Leis. Sci. 1988, 10, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, S.; Hardiman, N. The direct physical, chemical and biotic impacts on Australian coastal waters due to recreational boating. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, S.; Ertural, S.M. The effects of marine tourism on water pollution. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2019, 28, 863–866. [Google Scholar]

- Łapko, A.; Strulak-Wójcikiewicz, R.; Landowski, M.; Wieczorek, R. Management of waste collection from yachts and tall ships from the perspective of sustainable water tourism. Sustainability 2018, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckl, N.; Birtles, A.; Farr, M.; Mangott, A.; Curnock, M.; Valentine, P. Live-aboard dive boats in the great barrier reef: Regional economic impact and the relative values of their target marine species. Tour. Econ. 2010, 16, 995–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, C.; Foresta, D.L. Yachting and pleasure crafts in relation to local development and expansion: Marina di Stabia case study. Coast. Process. 2011, 149, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreizis, Y.; Potashova, I.; Ilin, I.; Kalinina, O. Yachting and coastal marine transport development in black sea coast of Russia. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 170, 5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J.; Krešić, D.; Kožić, I. Critical factors of the maritime yachting tourism experience: An impact-asymmetry analysis of principal components. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, S30–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitude and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Joyce, N.; Sheikh, S.; Cote, N.G. Knowledge and the prediction of behavior: The role of information accuracy in the theory of planned behavior. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Abraham, C. Conscientiousness and the theory of planned behavior: Towards a more complete model of the antecedents of intentions and behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 1547–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitri, R.; Karim, S.; Hera, O.; Heru Purboyo, H.P.; Arief, R. Applying knowledge, social concern and perceived risk in planned behavior theory for tourism in the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 809–828. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.H.; Stein, L.; Heo, C.Y.; Lee, S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for green initiatives of the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.M.; Zhang, Y.K. Variance analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for low-carbon products in China based on scenario experiment with carbon labeling. China Soft Sci. 2013, 7, 61–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.U.; Liu, G.; Zhao, M.; Chien, H.; Lu, Q.; Khan, A.A.; Ali, M.A.S. Spatial prioritization of willingness to pay for ecosystem services. a novel notion of distance from origin’s impression. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Are consumers willing to pay for Green Practices at Restaurant? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalish, S.; Nelson, P. A comparison of ranking, rating and reservation price measurement in conjoint analysis. Mark. Lett. 1991, 2, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Yang, Q. Empirical research on the audience WTP of Chinese professional soccer games and the influence factors. J. Xi’an Educ. Univ. 2019, 36, 300–308. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Breidert, C. Estimation of Willingness-to-Pay: Theory, Measurement, and Application; Wirtschaft Suniversitat Wien: Vienna, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.H.; Luan, W.X. Factors influencing yacht tourism consumption behavior based on the TAM-IDT Model. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 60–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.W.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zha, A.P. An empirical study on the influencing factors of rural residents’ tourism consumption intention. Lanzhou Acad. J. 2011, 3, 57–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, H.; Leach, T.C.; Rowley, D.J. Sabre yachts: A case study. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2008, 9, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.L.; Huang, Z.F.; Hou, B. Research progress and enlightenment on the relationship between values and tourism consumption behavior. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 117–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. A Comparative Study on Tourists’ Cross-Cultural Tourism Behavior; Dongbei University of Finance and Economics: Dalian, China, 2011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rohm, A.J.; Milne, G.R.; McDonald, M.A. A mixed method approach for developing market segmentation typologies in the sports industry. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Kimmel, S.K. A comparison of leading theories for the prediction of goal-directed behaviours. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 34, 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, C.K.; Klenosky, D.B. The influence of push and pull factors at Korean national parks. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phau, I.; Lee, S.; Quintal, V. An investigation of push and pull motivations of visitors to private parks: The case of Araluen botanic park. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Trib. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Lobato, L.; Solis-Radilla, M.M.; Moliner-Tena, M.A.; Sánchez-García, J. Tourism destination image, satisfaction and loyalty: A study in Ixtapa-Zihuatanejo, Mexico. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Noe, F. Satisfaction in Outdoor Recreation and Tourism. In Cases in Tourism Marketing; Laws, E., Ed.; Continuum Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.K.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Y.; Guo, T.T. Investigation and analysis of aural residents’ willingness to pay for online consumption. Manag. World 2018, 34, 94–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Wicker, P. Estimating willingness to pay for a cycling event using a willingness to travel approach. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Saleh, R.M. How green our future would be? An investigation of the determinants of green purchasing behavior of young citizens in a developing country. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13436–13468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnmacht, T.; Husser, A.P.; Thao, V.T. Pointers to Interventions for Promoting COVID-19 Protective Measures in Tourism: A Modelling Approach Using Domain-Specific Risk-Taking Scale, Theory of Planned Behaviour, and Health Belief Model. Frontier in Psychology 2022, 13, 940090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkes, C.; Butzmann, E. Motivating Pro-Sustainable Behavior: The Potential of Green Events—A Case-Study from the Munich Streetlife Festival. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Tuková, Z.; Jibril, A.B. The role of social media on tourists’ behavior: An empirical analysis of millennials from the czech republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.J. Physicians’ acceptance of electronic medical records exchange: An extension of the decomposed TPB model with institutional trust and perceived risk. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2015, 84, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Popa, A.; Sun, H.Z.; Guo, W.F.; Meng, F. Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L. SPSS Statistical Application Practice: Questionnaire Analysis and Applied Statistics; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2003; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Payeras, M.; Jacob, M.; Alemany, M.; Garcia, M.A. The yachting charter tourism SWOT: A basic analysis to design marketing strategies. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2011, 6, 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mcintosh, A.J.; Thyne, M.A. Understanding tourist behavior using means–end chain theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.; Gnoth, J. Japanese tourism values: A means- end investigation. J. Travel Res. 2010, 50, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B. The Domestic Market Is Fully Recovering and the Tourism Economy Is Recovering. Available online: http://travel.china.com.cn/txt/2021-04/09/content_77392124.html (accessed on 9 November 2021). (In Chinese).

- Wang, E.P.; Gao, Z.F. Chinese consumer quality perception and preference if traditional sustainable rice produced by the integrated rice-fish system. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubor, A.; Milicevic, N.; Djokic, N. Social-psychological determinants of Serbian tourists’ choice of green rural hotels. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.X.; Kang, S.K.; Lee, C.; Choi, Y.J.; Reisinger, Y. Understanding views on war in dark tourism: A mixed-method approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Caizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from COVID-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Meaning | Variable Types | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | Gender | 1 = male, 2 = female | Nominal |

| Age | 1 = under 24-years-old, 2 = 25–34-years-old, 3 = 35–44-years-old, 4 = 45–55-years-old, 5 = over 55-years-old | Ordinal | |

| Education | 1 = junior high school or below, 2 = senior high school or technical secondary school, 3 = junior college or bachelor’s degree, 4 = master’s degree or above | Ordinal | |

| Income | 1 = below 50,000, 2 = 50,000–100,000, 3 = 100,000–150,000, 4 = 150,000–200,000, 5 = 200,000–300,000, 6 = 300,000–500,000, 7 = more than 500,000 (yuan) | Ordinal | |

| Family Structure | 1 = unmarried, 2 = married without children, 3 = married with minor children, 4 = married with adult children | Nominal | |

| Psychological variables [67,68] | Value | I like challenges and adventures. | Ordinal |

| Attitude (AT) | AT1. I am interested in yachting tourism. AT2. Yachting tourism allows me to experience a different kind of fun. AT3. Yachting tourism has expanded my horizon. | Ordinal | |

| Subjective Norm (SN) | SN1. My family or relatives often participate in yachting. SN2. My friends or colleagues often participate in yachting. SN3. My family or relatives think I should participate in yachting. SN4. My friends or colleagues think I should participate in yachting. | Ordinal | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | PBC1. I have sufficient income to participate. PBC2. I have plenty of time to participate. PBC3. I have the ability to deal with problems arising from yachting tourism. | Ordinal | |

| Behavioral variable [66,67,68,69,70] | Past experience (PE) | The frequency of yachting tourism in the past: 1 = 0 times, 2 = once in many years, 3 = once in 3 years, 4 = 1 once in a year, 5 = multiple times in a year. | Ordinal |

| Perceived institutional variables [52,71] | Institution (INS) | INS1. The social security system is sound. INS2. The yacht safety management system is perfect. INS3. Tourism epidemic prevention and management measures are comprehensive. | Ordinal |

| Perceived destination attributes variables [37,55,72] | Core attributes (CA) | CA1. The destination has a good natural environment, unique scenery and high tourism value. CA2. Onshore destinations are rich in culture, sports, entertainment, shopping and other activities. CA3. Basic service facilities of the marina are complete (water, electricity, sanitation, technical services, etc.). CA4. Developed destination tourism transportation system. | Ordinal |

| Peripheral attributes (PA) | PA1. The service level of yachting tourism practitioners is high. PA2. The promotion of yachting tourism is strong. PA3. The destination is in good security. PA4. Easy access to information on yachting tourism. | Ordinal | |

| Prefer Motor Boats | Prefer Non-Motor Boats | Prefer Motor Boats | Prefer Non-Motor Boats | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Items | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| WTP | 1.94 | 1.043 | 1.52 | 0.813 | PBC3. Ability | 3.05 | 0.993 | 2.98 | 0.827 |

| Age | 2.12 | 0.906 | 2.432 | 1.161 | PE | 3.60 | 1.375 | 2.43 | 1.329 |

| Education | 2.79 | 0.623 | 2.53 | 0.744 | INS1. Security | 2.46 | 1.008 | 2.49 | 1.013 |

| Income | 2.71 | 1.435 | 2.10 | 1.124 | INS2. Safety | 2.62 | 0.975 | 2.72 | 0.848 |

| Value | 3.47 | 0.835 | 3.25 | 0.926 | INS3. Prevention | 2.85 | 0.952 | 2.82 | 0.778 |

| AT1. Interest | 3.54 | 0.754 | 2.99 | 0.823 | CA1. Environment | 3.17 | 1.253 | 3.16 | 1.325 |

| AT2. Fun | 3.75 | 0.776 | 3.46 | 0.759 | CA2. Onshore | 3.06 | 1.151 | 2.95 | 1.175 |

| AT3. Meaningful | 3.67 | 0.721 | 3.17 | 0.835 | CA3. Marina | 3.11 | 1.224 | 3.15 | 1.321 |

| SN1. Family | 2.77 | 0.943 | 2.51 | 0.906 | CA4.Transportation | 3.11 | 1.239 | 3.16 | 1.355 |

| SN2. Friends | 2.84 | 0.932 | 2.57 | 0.961 | PA1. Service | 2.90 | 1.135 | 2.75 | 1.125 |

| SN3. Relatives | 2.97 | 0.905 | 2.61 | 0.940 | PA2. Promotion | 2.94 | 1.163 | 2.68 | 1.070 |

| SN4. Colleagues | 2.94 | 0.891 | 2.65 | 0.971 | PA3. Public security | 3.16 | 1.170 | 2.98 | 1.216 |

| PBC1. Income | 3.14 | 1.104 | 3.00 | 0.852 | PA4. Information | 2.77 | 0.945 | 2.82 | 0.815 |

| PBC2. Time | 2.93 | 0.968 | 2.97 | 0.803 | |||||

| Items | Factor Loading | Cumulative Variance Contribution Rate | Item-Total Correlation | Alpha If Item Deleted | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude (AT) | 0.684 | ||||

| AT1. Interest | 0.685 | 61.596% | 0.396 | 0.718 | |

| AT2. Fun | 0.804 | 0.510 | 0.572 | ||

| AT3. Meaningful | 0.856 | 0.593 | 0.455 | ||

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | 0.702 | ||||

| PBC1. Income | 0.763 | 62.660% | 0.485 | 0.651 | |

| PBC2. Time | 0.818 | 0.553 | 0.565 | ||

| PBC3. Ability | 0.792 | 0.520 | 0.609 | ||

| Subjective norm (SN) | 0.930 | ||||

| SN1. Family | 0.935 | 82.696% | 0.793 | 0.923 | |

| SN2. Friends | 0.923 | 0.879 | 0.894 | ||

| SN3. Relatives | 0.896 | 0.859 | 0.901 | ||

| SN4. Colleagues | 0.882 | 0.815 | 0.916 | ||

| Institution (INS) | 0.840 | ||||

| INS1. Security | 0.914 | 76.185% | 0.671 | 0.819 | |

| IN12. Safety | 0.854 | 0.783 | 0.700 | ||

| INS3. Prevention | 0.849 | 0.671 | 0.810 | ||

| Core attributes (CA) | 0.942 | ||||

| CA1.Environment | 0.939 | 85.324% | 0.886 | 0.917 | |

| CA2. Onshore | 0.936 | 0.820 | 0.938 | ||

| CA3. Marina | 0.923 | 0.884 | 0.918 | ||

| CA4.Transportation | 0.897 | 0.862 | 0.925 | ||

| Peripheral attributes (PA) | 0.899 | ||||

| PA1. Service | 0.921 | 83.377% | 0.816 | 0.843 | |

| PA2. Promotion | 0.920 | 0.814 | 0.846 | ||

| PA3. Public security | 0.898 | 0.775 | 0.880 | ||

| Variables | Model I; (Population Sample) | Model II (Prefer Motor Boat) | Model III (Prefer Non-Motor Boat) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Sig. | β | SE | Sig. | β | SE | Sig. | |

| Age | 0.463 * | 0.256 | 0.070 | ||||||

| Education | 0.356 ** | 0.155 | 0.022 | 0.651 *** | 0.214 | 0.002 | |||

| Income | 0.420 *** | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.65 1 *** | 0.134 | 0.000 | |||

| Family Structure 3 | 1.200 * | 0.734 | 0.100 | ||||||

| AT | 0.302 *** | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.245 ** | 0.098 | 0.012 | 0.318 *** | 0.086 | 0.000 |

| PBC | 0.125 ** | 0.050 | 0.013 | ||||||

| PE | 0.345 *** | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.627 *** | 0.115 | 0.000 | |||

| INS | 0.112 ** | 0.055 | 0.042 | ||||||

| CA | 0.182 *** | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.287 *** | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.161 *** | 0.034 | 0.000 |

| Sample size | 453 | 189 | 264 | ||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.378 | 0.469 | 0.354 | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.426 | 0.516 | 0.416 | ||||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 764.282 | 326.673 | 382.877 | ||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, Y.; Zheng, R.; Parmak, M. Factors Influencing the Willingness to Pay in Yachting Tourism in the Context of COVID-19 Regular Prevention and Control: The Case of Dalian, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013132

Yao Y, Zheng R, Parmak M. Factors Influencing the Willingness to Pay in Yachting Tourism in the Context of COVID-19 Regular Prevention and Control: The Case of Dalian, China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013132

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Yunhao, Ruoquan Zheng, and Merle Parmak. 2022. "Factors Influencing the Willingness to Pay in Yachting Tourism in the Context of COVID-19 Regular Prevention and Control: The Case of Dalian, China" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013132

APA StyleYao, Y., Zheng, R., & Parmak, M. (2022). Factors Influencing the Willingness to Pay in Yachting Tourism in the Context of COVID-19 Regular Prevention and Control: The Case of Dalian, China. Sustainability, 14(20), 13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013132