Abstract

Due to public opposition against the unsustainability of hosting the Olympic Games, the International Olympic Committee adopted Olympic Agenda 2020 to adjust the event requirements to address modern society’s sustainability concerns. Since its implementation, the Agenda has driven important changes regarding the planning and organization of the Olympics, including the possibility of regions being hosts. This allows the sprawl of Olympic venues over larger territories, theoretically facilitating the alignment of event requirements with the needs of the intensively growing contemporary urban areas. However, the larger the host territory, the more complex becomes its mobility planning, as transport requirements for participants still have to be fulfilled, and the host populations still expect to inherit benefits from any investments made. The objective of this paper is to identify and discuss new challenges that such modifications bring for mega-event mobility planning. First, based on the academic literature of case studies of previous Olympic cities, a theoretical framework to systematize the mobility problem at the Olympic Games is proposed for further validation, identifying the dimensions of the related knowledge frames. Second, the mobility planning for the case study of the first ever Olympic region—the Milan–Cortina 2026 Winter Games—is described. Using this case study, the proposed framework is then extrapolated for cases of Olympic regions in order to identify any shifts in the paradigm of mobility planning when increasing the spatial scale of Olympic hosts. Conclusions indicate that, if properly addressed, unsustainability might be mitigated in Olympic regions, but mega-event planners will have to consider new issues affecting host communities and event stakeholders.

1. Introduction

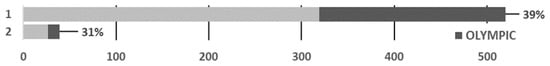

The Olympic Games are the largest mega-event in the world, involving around 200,000 participants among athletes, media, sponsors, organizations, and staff, and an uncertain number of spectators accounting for 4 to 8 million ticket sales [1,2]. To meet the requirements of an event of such magnitude, hosts adopt urban strategies that have the potential to catalyze urban development, of which transport system improvements are a part [3]. In fact, from 2010 to 2016, transport has shown to be the largest key area of investment from non-OCOGs’ (Organizing Committees of the Olympic Games) funds, representing 39% of the costs—higher than the venues, which account for 31% [4]. Moreover, for being indirect capital costs for general infrastructure, transport investments are usually not considered in total budgets, many times dodging public scrutiny [5]. Thus, to reduce the risk of post-event underutilization, transport infrastructure improvements require careful planning that guarantees the alignment of interventions with the long-term development plans of the host territories [6].

The importance of investing in transport infrastructure for hosting mega-events was first noticed in the 1952 Winter Olympic Games, in Oslo, due to the long travels that athletes and spectators needed to undertake to access isolated locations, in challenging terrains and in adverse weather conditions [7]. Later, in the 1968 Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City, the dispersed Olympic city model adopted by the organizers proved, in the wrong way, the need for good mega-event mobility planning—an edition that became known as the “Games of long walks” [8,9]. However, until recently, mega-event mobility was mostly seen as a temporary issue as, objectively speaking, its role is to provide additional capacity to the hosts’ transport system in order to cope with the temporary extra demand during the event [6,10]. For that reason, before the 21st century, few transport legacies resulted from the Olympic Games [3].

Mega-event mobility planning became extremely recognized after the fiasco of the 1996 “Centennial Games” in Atlanta when, due to huge congestion problems, athletes and spectators missed competitions [3]. From then on, subsequent editions adopted innovative mobility strategies to cope with the event-related demand and improve their transport systems, creating lasting legacies for their populations, almost always in line with the hosts’ long-term goals [11]. Philippe Bovy, a former primary transport advisor of the IOC (International Olympic Committee), stated that he has “seen quite a few sports venues turned white elephants, but never seen real transport white elephants. The reason is quite simple. (…) Successful host cities develop a vision, not only of their proposed mega-event, but also of their long-term development as boosted by the Games. (…) In many cities, the unique chance that lies in the momentum brought by the Games is the actual re-activation of long-needed projects that had been shelved for political or economic reasons.” [12] (pp. 16–17). However, any large transport infrastructure investment incurs opportunity costs, is always associated with environmental impacts, and might increase social inequity and polarization.

Nowadays, mobility planning for the Olympic Games is undoubtedly crucial to guarantee the smooth operation of all activities, being one of the evaluation criteria when electing hosts [3]. Moreover, hosts use such events as globalization and city-branding strategies for economic development [13] and, therefore, wish to “present a flawless image of a perfectly functioning city to the world” [6] (p. 399). However, mobility planning for these events is extremely challenging and complex for transport planners, as it presents high demands, concentrated in time and space, with a very short duration, and very low frequency (mostly once in a lifetime) [10]. Economic, social, and environmental considerations also add to the equation. Thus, planners are required to provide the adequate level of service for the event’s and host’s stakeholders without incurring pointless expenditures, taking into consideration the sustainability of the interventions, and striving to create lasting legacies to fulfill the host’s transport system gaps and to serve the resident population—which ultimately paid for such improvements.

In order to mitigate criticisms against the public investments related to the hosting of the Games, the IOC adopted in December 2014 Olympic Agenda 2020 [14] (and later in February 2021, Olympic Agenda 2020 + 5). The Agenda aims at increasing the sustainability of the event and has already driven changes in the definition of the ‘host’, which is no longer required to be a city [15]. That brings the possibility of different urban areas, such as metropolises or mono-/poly-centric regions, becoming hosts of the Olympic Games. However, as urbanization grows and populations are even more dispersed in regions, and as technological innovations in transport and communication increase, new challenges emerge for transport and mobility planning, requiring ever more sustainable solutions [16]. In addition, while the IOC promotes the hosting of the Olympic Games as a tool for sustainability of contemporary urban areas, the planning for the generation of legacies, such as the mitigation of air pollution or traffic congestion [17] (see also [18,19]), needs to consider these new challenges and effectively develop strategies to achieve such goals. The edition of Milan–Cortina 2026, which is undergoing its planning stage, will be the first to be hosted at a macroregional scale, being the only case of an Olympic region, thus representing an interesting case study for this research. Its analysis can potentially indicate how the move towards an Olympic region will affect the mobility planning for the transport services during the event and for the generation of legacies for host populations.

The main objective of this paper is to explore and discuss how mobility planning paradigms in the context of the Olympic Games are expected to change for cases of regional hosts. What new dilemmas will mega-event planners face? How will the delivery and the legacy of the event be affected? How can it enhance sustainability in host territories? The answers to these questions can prove valuable for better understanding how the move towards regional Olympic hosts can contribute to the adaptation of the event for an ever more economically, socially, and environmentally concerned society. The methodology of this study is divided into three steps. First, resorting to a semisystematic review of the existing literature, a comprehensive framework to systematize and describe the mobility problem at the Olympic Games is proposed, identifying the knowledge dimensions into which the problem can be divided. Second, the mobility planning for the Milan–Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics is presented as the first and only case study of an Olympic region. Third, based on the presented case study, exploratory research is carried out to extrapolate the proposed framework to cases of Olympic regions, and to examine how each of the identified knowledge dimensions can be affected in such cases. A discussion of how urban sustainability can be enhanced in Olympic regions is also carried out. Conclusions are drawn in the last section.

2. The Mobility Problem at the Olympic Games

Although extremely important for the success of mega-events, mobility at the Olympic Games has generally been overlooked by scholars. In this section, a conceptual and comprehensive framework is developed to systematize the mobility problem at the Olympic Games.

2.1. Conceptualization and Framework of the Mobility Problem at the Olympic Games

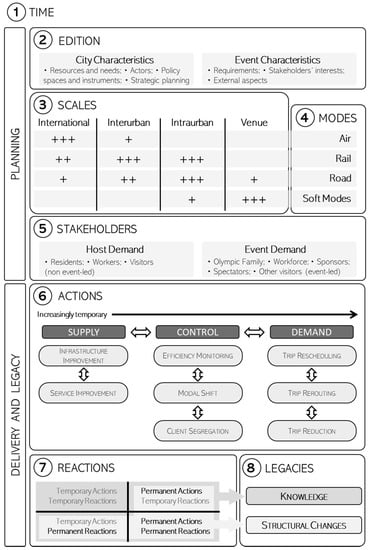

The proposed framework was developed on the basis of a semisystematic literature review of mega-event mobility studies and, in particular, of the Olympic Games, as it is the biggest mega-event in the world, with the most complex, challenging, and largest exceptional transportation demand [20,21]. The results of this methodological step indicate the existence of eight dimensions of knowledge in the mobility problem: 1. time; 2. editions; 3. scales; 4. stakeholders; 5. modes; 6. actions; 7. reactions; and 8. legacies (see Figure 1). Together, they constitute a tool for assisting in planning processes and in understanding the mobility problem faced by mega-event planners.

Figure 1.

Systematization of the mobility problem at the Olympic Games. Own creation.

2.1.1. Time: The Mobility Problem Concerns Three Time Periods

Mega-event mobility can be divided into three different time periods [22]. The most obvious is the management of the transport system’s performance during the Games. Afterwards, the host is left with impacts and legacies that affect its territory and population, which are the justification for hosting the event [23]. Prior to both periods lies the decision-making stage.

Since the implementation of Olympic Agenda 2020, the life cycle of the Olympic Games has had no specific starting date, with the candidature processes conveniently starting when appropriate. The period before the delivery of the event is the planning stage, when decision making occurs for all the different decision levels: strategic, tactical, and operational [17]. The planning stage is divided into two processes, the candidature process, and the preparation process, separated in time by the election of the host, which, prior to Olympic Agenda 2020, occurred seven years before the event. The new candidature process is furthermore divided in two stages: a non-committal continuous dialogue, when the IOC discusses with potential interested parties their initial ideas; and a formal targeted dialogue, during which the candidature is formalized for one or more preferred hosts, and when proposals are refined [24]. At the time of the election, most of the strategic guidelines are already defined as, to assess the quality and feasibility of the proposals, projects of the candidates are evaluated based on a set of criteria, in which ‘transport’ is included. After the election, the preparation process starts. In order to produce results just in time and to reduce the costs of too early or too late deliveries, during this phase, the IOC encourages hosts to spend the first years focused on strategic and tactical levels of decision and the last on the detailed operational planning, readiness, and delivery [4].

The second period is the delivery stage, which is the shortest, lasting for about two months from the opening of the Olympic Village to the closing of the Paralympic Village. It encompasses the Olympic competitions and, afterwards, the Paralympic ones, as well as a period of limited services prior to and after both. Between them, there is a period of adaptation for the Paralympic Games, during which measures for improving the transport fit and accessibility for disabled people are carried out [25]. The delivery stage represents the highest transport demand during the entire cycle, defying challenges to transport networks and infrastructure during place- and time-specific peak demands [6]. Additionally, particular concerns of security, reliability, efficiency, comfort, flexibility, and sustainability are required for all commuters during the event [26].

After the event, when temporary actions are lifted and the city reverts to its new permanent form, the Olympic cycle enters a continuous time period, the legacy stage. Depending on the strategies defined earlier and their implementation success, the territory and its population are left with positive or negative effects in their transport system and network. Good or bad, if short-termed, these effects are only small impacts, but if long-termed, they become legacies that change the territory of the host forever [27]. As transport measures, infrastructure, and assets are planned for long lifespans, throughout time, the impacts of the event eventually diffuse within the life of the host territory and community [28].

2.1.2. Editions: The Mobility Problem Is Edition-Specific

Although many similar features are always found from edition to edition, the mobility problem at the Olympic Games is edition-specific [3]. It depends on two sets of characteristics: the host characteristics and the event characteristics [29]. On the one hand, the host characteristics regard, among others, the spatial, social, economic, environmental, cultural, and political aspects of each host territory and community. They set the starting point for the design and implementation of measures, indicating the available physical, economic, and technological resources, the networks of actors involved, and the policy spaces and instruments [26,30,31,32]. For decision making in mega-event mobility planning, of great importance are the location and the urban/spatial form of the host territory, where are included the transportation habits of the host populations, the resilience and versatility of the transport system and network, and the location and quality of the existing transport infrastructure, as well as the location of other key facilities for sports, culture, tourism, recreation, services, etc. [33]. Moreover, all decisions have to be framed within the host’s long-term strategic planning in order to guarantee an appropriate public investment that fits the needs of the population [32]. In this regard, the choice of existing key competition and non-competition venues, as well as the location choice for temporary or new venues (the venue masterplan), highly influence the mobility problem to be solved. Another very relevant factor influencing mega-event mobility planning is the climate conditions of the host territory, especially in the context of the Winter Olympics, as measures have to be put into practice to make sure that the transport operations are not affected by adverse situations [7,33].

On the other hand are the event characteristics regarding the conditions in which the event has to be held. They are mostly tied with the requirements of the event, which are usually kept unchanged, with only minor adjustments from edition to edition, driven either by the new stakeholders’ requirements or previous hosts’ experiences [14]. One example is the Olympic Programme, as new sports can be added or existing ones removed from the list, and may require specific changes in the transportation planning for some stakeholders. For example, sports that require a specific natural/topographic environment, such as surfing, rowing, golf, or snow sports, can imply the transport of some stakeholders to more remote areas with less-efficient transport infrastructure. Additionally, other external aspects that result from worldwide, continental, or domestic issues specific of the contemporary time also constrain mega-event planning. For example, following the Munich massacre in 1972 at the Olympic Village, the planning of the subsequent edition in Montreal 1976 suffered modifications for security reasons [8]. For the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, besides all the inconveniences related to the postponement due to the pandemic crises, transport operations during the event had to be adapted to strict public health security measures. Economic crises affecting the hosting of the event are also examples of these types of external aspects.

2.1.3. Scales: The Mobility Problem Occurs at Different Spatial Scales

From the time the event starts until it ends, stakeholders make use of the transport network at different spatial scales [34]. Most arrivals and departures are transport operations at international scale, with peaks temporally placed a few days prior to and after the competition events.

National and interurban transport are relevant for some airport–city connections and for certain competition areas outside the host city, as is the case with football and events requiring specific geographic conditions or held in natural landscapes. This is especially relevant for the Winter Olympics, as snow sports are held in remote mountain venues located in less populated areas [7].

Olympic transport at the intraurban scale is “the most complex transport operation to cope with” [21] (p. 52), since it entails high additional event-led demand in transport systems and networks usually already at capacity [35,36]. Additionally, a crowding-out effect usually occurs (see Section 2.1.5.), which, although resulting in reduced demand, complexifies forecasts [32].

At the venue scale, mobility and accessibility are particularly relevant, not only between transport gateways and event sites (last mile), but also at the surroundings of the key venues and within large event precincts, such as Olympic Parks [28,37]. One example is the opening ceremony where, besides the spectator and workforce affluence to the stadium, hundreds of buses need to be stashed in line and synchronized to bring/take the athletes on time to/from the opening parade [6].

2.1.4. Modes: Supply Is Provided by Different Modes of Transport

Buses, trains, taxis, the airport, and roads and parking have always been the five major transport pressure points in Olympic transport networks [38]. Yet, recent editions are taking advantage of technological innovation to develop alternative modes, such as flying taxis or autonomous vehicles. Shipping also plays an important role for delivering cargo during the preparation for the event, which, namely for sustainability reasons, requires careful planning. It is also important to denote that, since some participants require specific allocated routes depending on their roles (see Section 2.1.5), there are differences in planning for the performance of the same modes for each type of user.

The coordination between all modes is essential for the smooth running of operations [31]. Moreover, the relevance of each mode is highly related with the regarded spatial scale. At the international scale, most visitors use air transport or, in some cases, high-speed rail [34]. Depending on the size of the host country, national and interurban transport might be performed by air transport as well, but high-speed and intercity railway connections play the most important role [2,34,38]. In intraurban transport, the different types of road and rail transport are prominent, with modal shift from private to public transport being crucial for the successful performance of the event transport network [2,10,37]. At the venue scale, soft modes such as walking, cycling, funiculars, or escalators prevail [3,7,28,39,40].

2.1.5. Demand Stakeholders: Demand Derives from Different Types of Stakeholders, Requiring Different Provisions and Priorities

Two groups of demand stakeholders share the Olympic transport network: the host regular commuters and the additional event visitors. With some exceptions, former Olympic cities had populations of 1 to 9 million inhabitants. In London, the population of about 9 million inhabitants (14 million in the metropolitan area) performed 25.5 million daily journeys, while in Sydney, its 5 million inhabitants represented a base load of around 14.4 million journeys/day. These commuters make regular use of the host cities’ transport systems, which, generally, are already operating at capacity, with significant base loads and congestion problems [20,36]. However, a phenomenon of crowding out is reported to occur during the Olympic Games, consisting of a decrease of common leisure activities performed by host populations and regular visitors to avoid congestion derived from the event [32].

The number of visitors to the host city varies from edition to edition and is not completely clear [31]. This uncertainty is not related with the unavailability of data but with the variability of data, complexifying the problem for transport planners [32]. The number of participants at the Olympic Games (the Olympic Family) is well known, as they receive accreditation at arrival. For the Summer editions, the demand is, approximately: athletes (≈11,000) and their team and sports officials (≈8000); accredited media (≈24,000); and members of the IOC, NOCs (National Olympic Committees), and IFs (International Sports Federations) (≈4000). Additionally, there are around 145,000 volunteers, members of the workforce, and logistics team. Sponsors account for around 50,000 people. Through the ticket sales (in the order of 4 to 8 million), local, domestic, and international ticketed spectators are estimated to be between 500,000 and 600,000 per day. Finally, there is an unknown number of nonaccredited media and nonticketed spectators, which are estimated to be around 10,000 and 150,000, respectively. In total, around 900,000 additional people use the transport system every day, accounting for an additional demand of around 1.5 million daily trips—reaching two million in peak days. For 17 days, additional demand reaches a total of 20 million journeys [12,21,37]. For the Sydney 2000 and London 2012 editions, it accounted for around 0.9 and 0.8 million trips per day, respectively, representing an increase of 6–7% and 3–4% of the base load [20,41]. While those numbers might not seem that much of a boost, this additional demand is highly time- and place-specific, and is undoubtedly sufficient to generate congestion, adverse environmental impact, and citizen opposition [2,36]. Note also that these numbers do not account for trips to attend other event live sites nor for non-event-related trips that spectators and participants might perform for recreation [20].

Each of these stakeholders requires a specific priority and type of transport service, and some of them are provided with drivers and vehicles for individual or collective use. In a simple way, there are five different transport systems: the Games stakeholder transport system; the athlete/NOC transport system; the technical official/IF transport system; the media transport system; and the public transport system. To ensure the required priority (e.g., athletes’ maximum travel time of 30/45 min from accommodation to competition sites), special routes are designated for some groups of stakeholders [21] (for details on transport provisions and priorities, see [3] (p. 107), [25] (p. 184), [26] (p. 57), [33] (p. 148), [42]).

2.1.6. Actions: Decision Making Results in Permanent/Temporary Actions Aimed at Matching Supply and Demand

Many studies focus on the actions taken for the improvement of mobility services of specific editions of the Games (see, for example, [1,21,35,38,40,41]). However, the two most comprehensive papers systematizing and grouping these types of actions are those of Kassens-Noor [3] and Currie and Delbosc [11]. Kassens-Noor groups them into five categories: transport infrastructure, management of transit operations, management of traffic operations, management of transport demand, and institutional policies. Currie and Delbosc also identify five categories: travel capacity creation measures, travel behavior changes or marketing, traffic efficiency measures, traffic bans, and public transport emphasis. Resorting mostly to these two references but also to other edition-specific research, Table 1 groups these actions together into three categories: actions on the supply side, actions on the demand side, and actions controlling the equilibrium between supply and demand. The actions on the supply side aim at increasing supply by infrastructure or service improvement, either in quantity or in quality, while the actions on the demand side aim at decreasing the demand, either by eliminating trips or by spreading them in space and time. Actions controlling the equilibrium between supply and demand include efficiency monitoring, modal shift, or client segregation. Note that actions in one category can also relate to other categories. For example, improvements in infrastructure/service for public transport can result in modal shift. Trip reschedule/rerouting can result in trip reduction (associated with the crowding out effect).

Table 1.

Systematization of actions adopted by Olympic hosts. Own creation Based on [1,2,3,11,21,35,38,40,41].

All actions can be permanent or temporary. Permanent actions are ideally targeted at the host population’s needs, with visions and objectives defined according to the host’s long-term planning. Temporary actions are those specifically designed to cope only with the temporary additional demand, being withdrawn when the event is over, as they are not considered necessary for the regular functioning of the city. Sometimes temporary actions become permanent if, during the event, they prove to be efficient in meeting the host population’s needs. In general, actions on the supply side tend to be permanent, while actions on the demand side tend to be temporary [3].

2.1.7. Reactions: Actions Result in Permanent/Temporary Planned/Unplanned Reactions

Actions taken to solve the mobility problem aim at producing reactions in the mobility system, which can also be permanent or temporary. It might be expectable that permanent actions result in permanent reactions and vice versa, but that is not always the case. For example, temporary actions to change the behavior of commuters during the event can result in a permanent change of habits, although usually lower in quantity [36]. Similarly, permanent actions can result in temporary reactions, but such examples are harder to materialize, since permanent actions are mostly on the supply side and transport is a derived demand, rarely consumed for its own sake and depending on other external consumptions [10,43]. Those cases are mostly related with the post-event use of new, extended or upgraded transport infrastructure giving access to sites with demand peak-flows during the event, but with a lack of post-event purposes. Important to note is that such permanent actions also result in permanent reactions of the system, namely the need for management and maintenance (and consuming of resources). These examples prove the existence of unplanned reactions, which can be positive or negative, and constitute part of the risks associated with hosting mega-events [29].

2.1.8. Legacies: All Pairs of Action–Reaction Create Legacies

In literature, legacies are usually considered as “all planned and unplanned, positive and negative, tangible and intangible structures created for and by a sport event, that remain longer than the event itself” [29] (p. 211). In accordance with this definition, in this paper is argued that all pairs of action–reaction have the ability to create legacies, no matter their temporary or permanent nature. They also have to be compatible with each other in order to produce positive and sustainable legacies.

Regardless of the permanent or temporary nature of actions, their permanent reactions (or impacts, as defined by Preuss) can potentially become structural changes, if they have consequences for people and space in different domains, and if they create a value-in-context, which alters over time and is bound to a territory [27]. Such structural changes can be of six types: urban development, environmental enhancement, policies and governance, human development, intellectual property, and social development [17]. In the case of mobility, these changes can be physical, as improved transport infrastructure and services, institutional, such as innovations in coordination and integration of the transport systems, or behavioral, which are switches in people’s attitudes [3]. In particular, most common physical changes include new or improved airport-city center connections, airport improvements, the creation and revitalization of parks with high-capacity transport access, new high-capacity transport modes, additional road capacity, and advanced intelligent transport systems [6].

Permanent actions with temporary reactions usually turn into negative legacies. For example, in Sydney 2000, a rail loop was built to access the Olympic Park, which, since the event, has not been particularly successful in attracting demand [3]. Investments were made in infrastructure (permanent action) for people to use the service only during the event (temporary reaction), but resulted in continuous maintenance costs (permanent reaction), which, over time, turned into a structural change with an undesirable value-in-context for the population (negative legacy). The IOC official definition of legacies disregards these cases, although recognizes their existence: “Legacy refers to the benefits, i.e., positive effects, for people, the host city/country and the Olympic Movement. It is important to clarify that, although the Olympic Movement’s aim is to strive to deliver positive outcomes, it does not overlook pitfalls and negative results from its activities” [17] (p. 15).

Finally, temporary actions resulting in temporary reactions produce knowledge legacies, as with all other action–reaction pairs. Bovy highlights that, “Olympic transport and traffic management schemes are more and more viewed as ‘real scale laboratories’ for urban and metropolitan mobility plan innovation and developments” [1] (p. 48). Irrespective of any positive or negative results of actions, intellectual legacies are always positive. They serve either the host policy-makers and planners for urban policy and decision making in daily routines or extraordinary activities (such as new events), or mega-event planners and stakeholders for adapting event characteristics and guiding future hosts through benchmark approaches [29]. These legacies are passed through the form of academic knowledge or practical experience. For the case of the Olympic Games, the latter is materialized by the IOC Transfer of Knowledge program [1,6], which plays a key role in reducing risks and “not re-inventing the wheel” [2] (p. 32).

2.2. Framing the Knowledge on Mega-Event Mobility Planning

Before the road traffic chaos occurring in the edition of Atlanta 1996, mega-event mobility planning used to be overlooked. Even the groundbreaking edition of Barcelona 1992, often indicated as the role model for mega-event urban planning, put little concern on mobility issues and transport legacies, as can be observed in the comparative analysis of Currie and Delbosc [11] (pp. 38–39). However, the lessons from Atlanta triggered an increasing relevance of mega-event transport planning, confirmed by the following establishment of the IOC Transfer of Knowledge program, starting in Sydney 2000 [6]. That was also the first edition to adopt free public transport policies for ticket-holders, following its major commitment of delivering “Green Games” [11]. In Athens 2004, exceptional efforts were put into mega-event mobility planning, including the extensive upgrade of transport infrastructure and services of the city that resulted in important and positive transport legacies—contrary to the legacies of sports venues [44]. From then on, the importance of mega-event mobility planning became clear, with all three subsequent summer editions engaging in major transport interventions, whose investments were justified by the resulting long-term benefits [21,40,45].

Olympic studies have grown significantly over the last years, especially in the field of urban development [46]. However, “transport has not emerged as a core focus in the event management literature and is often peripheral to the tourism destination management literature,” with most studies being descriptive, event-specific, and driven by the agendas of event organizers [10] (p. 303). Moreover, they are mainly focused on the short-term delivery for the event, with only a few addressing post-event impacts and legacies [10,47]. Even fewer have regarded aspects of the planning and decision-making processes behind such short- and long-term deliveries [22].

Figure 2 shows the number of academic papers published on the topic of mega-event planning in the Web of Science database. Additionally, it shows the number of those papers addressing mega-event transport and mobility planning—accounting for 8% of the total—as well as the percentage of Olympic studies in both. Most of these studies date from 2015 onwards, with none of the mobility-related papers dating older than 2011. Naturally, these data regard only the Web of Science database, but are sufficient to make conclusions about the lack of mega-event mobility studies.

Figure 2.

Number of scientific papers (1900 to 2020) with ‘mega-event’ (1), or ‘mega-event’ and ‘mobility’, ‘transport’, ‘transportation’, or ‘accessibility’ (2) in their titles, abstracts, or keywords. Shadow percentages also include ‘Olympic’ (source: Web of Science).

Therefore, the framework proposed in this paper can serve as setting the base for mega-event mobility studies. Although a proper validation method is lacking, all studies and knowledge on mega-event mobility potentially fit the developed framework. For example, Frantzeskakis and Frantzeskakis [35] addressed the planning phase of the Athens 2004 Olympics, at the intraurban scale, simulating the demand from all stakeholders for road modes of transport and the effect of actions on reactions and legacies. Parkes, Jopson, and Marsden [36] focused on the effectiveness of the actions taken to change the host stakeholders’ mobility behavior, at the intraurban scale, during and after London 2012, thus assessing the temporary nature of reactions. The study of Pereira [47] assessed the consequences of the physical transport legacy, after Rio 2016, in regard to public transport accessibility for a specific type of host stakeholders. Odoni, Stamatopoulos, Kassens-Noor, and Metsovitis [48] studied the planning phase of the Athens International Airport in regard to demand forecasts for the international and venue scales, describing the actions resulting from the decision-making process for both air and soft modes. Other studies may address many editions, as those of Kassens-Noor [3] and Currie and Delbosc [11], and can also be more generic, as the conceptual framework of Robbins, Dickinson, and Calver for event legacies [10].

3. Towards an Olympic Region

The next sections explore the effects of increasing spatial scales in the previously proposed framework. First, the case study of the Milan–Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic Games is presented as the only example of an Olympic region to date. Analysis is conducted using mostly the official candidature dossier of the Milan–Cortina bid [49], whose reference will, hereinafter, be omitted. Basing the analysis solely on such a reference can be limitative of conclusions, but in this case, it represents the best source to assess the planning of the event, as it shows the vision, objectives, concerns, and priorities of mega-event planners. In other words, the candidature files allow us to understand how the edition was planned and how such planning was affected by the spatial configuration of the host, even though the extent to which the plans are to be fully carried out is still to be seen. Second, and using the case as a reference, the framework’s dimensions are extrapolated to a regional spatial scale in order to explore how Olympic regions can affect concerns in mobility planning. Finally, a discussion is carried out in regards to the potential of Olympic regions for enhancing the sustainability of the Olympic Games.

3.1. Milan–Cortina 2026: The First Olympic Region

The Winter Olympics are considerably smaller when compared to the Summer Olympic Games. In Pyeongchang 2018, 2833 athletes participated and there were 13,751 accredited members of the media. The volunteer workforce accounted for 22,400, a number that, when compared to the usual 70,000 volunteers for the Summer Games, is representative of the size difference between the events [50]. However, mobility planning at the Winter Games is subject to additional challenges, as accesses to isolated mountain areas are difficult, adverse weather conditions might occur, and because mountain localities have relatively small populations and fewer resources, sustainable legacies are harder to guarantee [7].

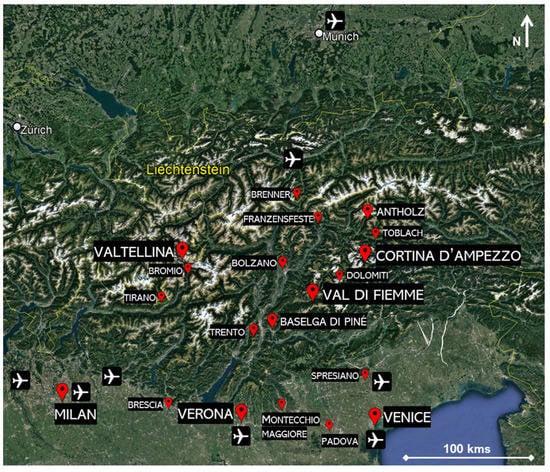

Milan and Cortina will be the hosts of the 2026 Winter Olympic Games. However, while the marketing name “Milan–Cortina 2026” suggests a cohosting of two cities, the venue masterplan includes four clusters of competition venues (Milan, Cortina, Val di Fiemme, and Valtellina), as well as two stand-alone competition sites (in Antholz and Baselga di Pinè), and the cities of Verona and Venice functioning as transport hubs in between clusters, with the former also being the host of the closing ceremony. Thus, the Italian candidature builds on a partnership within the Northern Italy city-region, supported by the administrative regions of Lombardy and Veneto and the two Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano/Bozen (Figure 3), with clusters distancing up to more than 400 km by car and with a travel time of four to five hours [51].

Figure 3.

Relevant areas of the Milan–Cortina 2026 mobility concept. Map Data: Google, ©2021 Landsat/Copernicus.

This spatial distribution, which can be considered both as a consequence of Olympic Agenda 2020 and the subsequent New Norm—allowing the sprawl of Olympic venues through several cities—and a political mediation to distribute consensus, does not rely on a specific spatial vision. However, it resembles a polycentric urban region with a strong dependency on a core city such as Milan, and definitely requires a strong mobility plan. Aiming at using the maximum number of existing or temporary venues to facilitate the delivery of sustainable legacies, three of the 14 competition venues are temporary, and only one previously planned permanent construction is to be carried, in the area of Santa Giulia, Milan [52]. The other competition venues, as well as the accommodation and transport solutions, foster the use and reuse of already existing or already planned facilities and infrastructure.

The two main international gateways will be the international airports of Milano Malpensa and Venezia Marco Polo. Additionally, the international airports of Milano Linate, Bergamo Orio al Serio, Verona, and Treviso, spread across the north of Italy, or the neighboring airports of Innsbruck and Munich, are also possible gateways to the Games area. The airport in Milan is the second largest airport in Italy and is currently underutilized, thus having enough spare capacity to accommodate additional demand. The airport in Venice, the third largest in Italy, has undergone recent improvements due to its yearly traffic growing rate of 6%, and expecting more improvements as part of its 2022–2035 master plan. A 3.5 km rail line connecting it with the city’s main station and to high-speed rail is also to be built, denoting the concerns for the improvement of intermodality in such a regionally spread Olympic host. Interesting to note is that the Games have accelerated a planned intervention in a city with no competition venues, with a distance of more than 150 km by car to the closest venue cluster.

It is expected that 55% of spectators will arrive from local and domestic areas, mostly by train, while 22% are expected at the two official gateway airports. The remaining 23% are expected to come from neighboring countries, arriving mostly by train or car. Milan is the national hub for high-speed rail, connecting the country to Switzerland, France, Spain, and Germany. The city has also a dense road network, with accesses to six motorways linking to other Italian regions and European neighbors, providing very high levels of reliability, safety, and security. Mountain clusters are provided with important motorway links—e.g., between Valtellina and Switzerland or Brenner and Cortina/Val di Femme—easily accessible from the two main airports via rail or road.

The spatial dispersion of venues will result in a widespread distribution of demand, which is estimated to be of 90,000 spectators per day, with a peak day demand of 130,000. Distributed by the four clusters, additional demand is not expected to cause much disturbance to ordinary traffic, being easily managed by the Milan transport system and by the permanent and temporary service improvements in the mountain clusters. Nonetheless, traffic restrictions are planned, and extraordinary public transport services will be created to compensate affected residents on mountain clusters. In the case of Milan, investment has already been made in introducing a congestion charge to reduce road traffic in the city center.

Between clusters, the train will be the preferred mode of transport, and the Games delivery will highly rely on the intermodal ‘high-speed backbone’ between Milan and Venice, via Verona, compounding road, rail, and air links. Verona will serve as a transport hub to access the Val di Fiemme cluster. Mobility between the Milan–Venice linear city and the Alp valleys will also be strengthened through road interventions. Table 2 summarizes the planned transport infrastructure interventions to be carried out, where some upgrades in the north–south regional rail and road links can also be noted.

Table 2.

Planned transport infrastructure interventions for Milan–Cortina 2026. Own creation based on [49].

Olympic Villages are planned in three clusters, and the remaining athletes will stay in existing hotels, thus guaranteeing the 30 min travel time between accommodation and competition sites. Bus shuttles for athletes and NOCs will be delivered, as well as dedicated routes for the Olympic Family and the general public. Accesses to park-and-ride facilities will be created in all clusters and will be free of charge for Games stakeholders. Parking at venues will not be allowed, as 100% use of public transport by spectators is expected. Public transport will operate 24 h per day between key venues and will be free for the Games stakeholders and ticketed spectators—something that is already practiced in the mountain clusters for skiers. Transport and venue concepts will be designed to promote the use of soft modes to access venues, creating opportunities to experience the city centers’ pedestrian routes.

In such a spatially widespread event, the transport operations have to be carefully coordinated. At the national level, the overall coordination falls in the responsibility of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, which supervises the infrastructure improvement and operation of public transport and organization, in close relation with many operators, entities, and public authorities. At the regional level, public transport systems are managed by the two regions of Lombardy and Veneto and the two autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano/Bozen. Local responsibilities are within the municipal level of governance. An Olympic Transport Steering Group will act as a consultative body, coordinating all entities, authorities, organizations, departments, and agencies at the regional level, and reporting to the Ministry. At the delivery stage, within the OCOG Transport department, a Transport and Traffic coordination center will be created to manage transport and to coordinate with other OCOG functional areas and the main operation center. This center will be based in the existing control center in Milan, coordinating with three satellite centers in each of the clusters, and will benefit from temporary expansions.

Information systems in real-time are already implemented by operators, and motorways are equipped with variable message signs. In Milan, to inform users of modal choice and travel time and cost, a service platform for integrated mobility will be developed, encompassing the local public transport network, rail transport, and car- and bike-sharing services. In Cortina, the FIS Alpine Ski World Championships Cortina 2021 served as a test event for the new ‘Smart Mobility Cortina 2021′ project, which, after the Games, will be put in service of the local population. Resorting to users’ information and communication systems, this technology integrates smart road technology to monitor infrastructure and environmental conditions to improve connectivity of people, vehicles, objects and infrastructure for safer, more comfortable, and more informed travelling. Additionally, contactless technology for ticketing systems will be implemented in all areas.

The 2026 Winter Olympics will also focus on the delivery of environmentally sustainable mobility, with the development of electric energy use: “By 2026, 50% of the bus fleet will be made up of electric vehicles, 25% hybrids, and the remaining diesel Euro 6. By 2030, the bus fleet in the Milano area will be 100% electric. (…) Our Generation 2026 ambitions are that all children born after 2010 will: (…) use sustainable means of transportation only” [49] (pp. 61, 65). It is also planned to use 5G technology to link the Olympic Village with other venues in Milan by electric driverless vehicles.

According to the candidature files, all permanent actions to be carried were planned prior to the Games and are in line with the long-term plans of the involved cities and regions. They contribute to improving the proximity between the Lombardy and Veneto regions in order to develop a smart, competitive, and well-connected region for future generations. Many of these improvements are part of the 2018–2023 Regional Development Program for Lombardy, which aims at promoting intermodality and accessibility to stations, strengthening integration between road and rail modes and their technical services, upgrading railway infrastructure and rolling stock, and improving the integrated pricing system and smart ticketing. Milan, in particular, shares a vision of reducing the city’s motorization rate and plans to shift to a barrier-free, fully accessible city. In this regard, the city will take the opportunity of the Games to continue the implementation of measures initiated for the Milano World Expo 2015.

3.2. The Mobility Problem in Olympic Regions

Based on the planning for Milan–Cortina 2026, as well as on the events currently surrounding its preparation process, the effects of expanding spatial scales of Olympic hosts on the different knowledge dimensions of the mobility problem are theoretically explored in this section. As with any qualitative exploratory research, this case is solely used to generate a formal hypothesis for a problem that is not yet clearly defined. Thus, it helps to understand the problematic, but does not provide conclusive results supported by evidence.

The effects in each dimension are presented individually, but it is important to keep in mind that they are intrinsically related and share synergies (e.g., preparation time depends on scale; modes depend on scale and stakeholders; actions depend on legacy plans and edition specificity; legacies depend on pairs of action–reaction, etc.).

3.2.1. Time: Compromising Timely Deliveries of Large Transport Infrastructure Works

In the Milan–Cortina case study, integration and connectivity between host cities shows as essential. To ensure a certain level of service in a spatially distributed Olympic network, large transport infrastructure works through long links might be required, implying longer construction times. This complexifies the preparations on the planning stage, as it is well known that transport infrastructure works are prone to delays. Moreover, with nonextendable deadlines, the Olympic Games are always subject to delays that significantly contribute to cost overruns [5,53,54]. As with any other mega-event, the 2026 Winter Olympics risk becoming an urgency and overpassing the usual processes of planning to guarantee completion on time (as previous mega-events in Italy, from Turin 2006 to Milan 2015).

Thus, the move towards an Olympic region might imply adaptations of the Olympic cycle to ensure that preparation times are enough to complete the planned projects without incurring extra costs. That can be achieved by rescheduling interventions to earlier periods or by expanding the duration of its planning stage. In this regard, the flexibility of the new candidature process introduced by Olympic Agenda 2020, if effectively implemented, might prove efficient to avert these potential situations.

3.2.2. Editions: Governance, (In)Equality, and Diversity Posing Opportunities and Threats

Each country has its own national attributes. However, each region, city, or neighborhood presents unique particularities, characteristics, and lifestyles, and have unique resources and needs. In the context of urban projects, the larger the territory and population, the more complex becomes the comprehensive planning, as each place requires specific implementation measures that planners have to consider and be aware of (as is definitely the case of Milan and Cortina).

The Olympic Games undoubtedly constitute a problem of governance, defined by a set of actors, networks, and policy spaces and instruments, in which urban governance is included [14,30]. To ensure a good governance system in an Olympic region, hierarchization and cooperation between actors require particular attention, as the number of involved parties increases and coordination between all becomes more difficult, and susceptible to conflicts and organizational chaos. On the other hand, a larger network of actors might provide opportunities for strengthening interrelationships and territory cohesion. In this regard, the Milan–Cortina candidature seems to have built a strong governance plan, contrary to the runner-up candidature of Stockholm–Åre 2026, which did not seem to have even considered the potential governance opportunities and threats [55]. However, for involving a large number of different entities, the difference between planning and implementing is evident in the case study of Milan–Cortina: while the candidature files pay a lot of attention to governance concerns, specifically referring the strengthening of partnerships within the macroregion as one of its main objectives, the implementation of such structures in practice is proving to be complex and highly fragmented.

The involvement of more cities also requires higher amounts of physical and economic resources. Smaller cities usually have less capability for investment to cope with the event’s demanding requirements, presenting, at the same time, the greater needs for transport infrastructure and service improvement. Because outer-city transport improvements are more costly and their sustainability is harder to guarantee, that can be particularly relevant for cases of Olympic regions. Although at a different spatial scale, the underutilization of the Sydney 2000 rail loop—connecting the city center with the Olympic Park in the suburbs—serves as an illustrative example. Furthermore, when contrasting the reality of smaller cities with globalization strategies pursued by other larger ones, disparities might become evident in terms of resource allocation equity (for example, ‘global’ Milan vs. ‘local’ Cortina). On the other hand, increased cooperation between different-sized hosts potentially boosts smaller cities’ development, which can benefit from strengthened interrelationships.

The larger the host territory, the more increased its diversity. In this context, diversity includes not only the cultural, social, and territorial characteristics of cities that contribute to marketing and city-branding purposes, but also the availability of diversified and specialized physical resources, namely the key Olympic venues. That is particularly evident in the case study of Milan–Cortina, as the organizers seem to have efficiently designed a venue masterplan that makes maximum use of the regional existing sports and transport facilities. However, the project lacks a clear macroregional vision, resembling more of a collection of existing projects, each with its own objectives.

It is still to be seen how Olympic sprawl will influence event characteristics. Event organizers can be tempted to enlarge the Olympic Programme, given the higher availability of quality sports venues, thus complexifying the mobility problem. Furthermore, larger territories are subject to more unpredictable risks and external occurrences.

3.2.3. Scales: Multi-Scaled Scattered Demand Destressing Infrastructure Capacity and Pressuring Service Efficiency

In general, the larger the host territory, the more dispersed the demand through the network, and the higher the offer of transport alternatives. For example, the Milan–Cortina transport concept provides numerous gateways for international stakeholders to enter or exit the country, exempting existing airports from undergoing expansions to cope with the additional (yet dispersed) demand. Long-distance transport is vital for the success of events hosted in large territories, as stakeholders might take several hours to travel between cities. At the interurban (or national) scale, the mobility problem at the Olympic Games becomes similar to the mobility problem at other sports mega-events, such as the FIFA World Cup or the UEFA European Championship, where connectivity between relatively distant cities is fundamental [34]. In the Milan–Cortina case study, the relevance of interurban transport is clearly perceived by the emphasis that planning puts in the combined system performance of the intermodal ‘high-speed backbone’ between Milan and Venice, together with other local infrastructure works for reducing travel times and improving service and comfort when travelling between host cities.

The dispersion of demand through the various host cities results in destress of intra-urban transport services in each of them. For Milan, while expansions and improvements on the subway and tram networks are to be carried, the candidature files many times refer to the fact that the existing transport system of the city is more than capable of handling the expected demand [49] (for example, p. 88). However, that is not the case for the smaller cities of Cortina, Bormio, or Livigno, where significant permanent and temporary measures will need to be implemented to improve mountain access and ensure proper intraurban mobility during the event (underlining the significance of disparities between different-sized host cities—see Section 3.2.2). Finally, unless venue masterplans of Olympic regions become less dependent on the agglomeration of facilities—such as Olympic Parks–at the venue scale, time- and place-specific peak demands will continue to exist, being defined by event schedules and venue capacities.

3.2.4. Modes: Highlighting the Relevance of Railway Transport and Intermodality

Each mode of transport has its particular purpose and relevance at each specific scale and for each type of stakeholder. In Olympic regions, that is not expected to change, but since interurban transport becomes fundamental in mobility concepts, railway transport (and namely, intercity high-speed trains) is expected to play an increasingly important role. Intermodality enhancement is also likely to become structural to the mobility visions of hosts. Together with the expected modal shift associated with them, both these observations can be deduced from the Milan–Cortina mobility concept. These changes are all in line with the new sustainable mobility concepts of contemporary urban regions. However—and also deducing from the Milan–Cortina case study–relatively distant venue clusters might encourage air travel, bringing new environmental challenges for mobility planners.

3.2.5. Demand Stakeholders: Impacting More Residents, Requiring More Personnel, and Potentially Attracting More Visitors

The number of residents affected and involved in the hosting of the Olympic Games is considerably higher in the Olympic region when compared to only one of the cities. However, given the dispersion of the event demand, the likelihood of affecting the daily routines of residents and workers is lower. In the case of Milan–Cortina 2026, more than 20 million inhabitants reside within two hours from the proposed Olympic areas. The candidature mentions that, in general, “there will be no disturbance to ordinary traffic” [49] (p. 76), but for the particular case of mountain clusters, planners expect to implement/enhance “a complementary compensatory public transport system for local residents, who might be impacted by road restrictions” [49] (p. 87). Once again, this highlights the disparities between different-sized host cities (see Section 3.2.2).

Scattered Olympic venues, namely non-competition facilities and infrastructure, are naturally expected to influence the number of event stakeholders, even if the size of the Olympic Family is kept unchanged. Notably, fewer opportunities for economies of scale in many activities can increase the number of, for example, accredited media, logistics, workforce, and volunteers. In addition, involving several cities increases the supply for activities of nonaccredited and non-ticketed visitors, such as tourist visitors, spectators attending live event sites, or media searching for Olympic content. Although it cannot be taken for granted, it is possible that the number of these visitors will also increase, depending on the promotion of such activities through the coordination of multiple factors and policies (e.g., efficient dimensions of event venues, accessibility to event venues and areas, as well as complementary cultural side events and policies by local institutions).

3.2.6. Actions: Same Strategies, Different Scales

The actions planned for the Milan–Cortina mobility concept do not differ much in nature from those presented in Table 1. However, the scale at which some of them are to be implemented significantly changes. On the supply side, infrastructure and service improvement expand through long links, with actions aimed at reducing long-distance travel times and improving the quality of public transport. On the demand side, few concerns are put in rescheduling, rerouting, or reducing trips, as the additional event demand becomes spatially distributed throughout the network. The exception is in mountain sites, where access to remote areas is provided by lower-quality infrastructure. In these cases, temporary measures to reduce the trips of regular commuters are considered necessary to ensure the proper delivery of the event.

The involvement of several administrative regions and respective traffic control entities complexifies the control of the equilibrium between supply and demand, namely because of governance issues and coordination between centers (see Section 3.2.2.). Furthermore, such coordination becomes particularly relevant for host regions, as multiple control centers exist, requiring integrated information and communication systems, an efficient distribution of roles and responsibilities and a well-structured hierarchy. In addition, improvements in intermodality become pivotal to promote modal shift from private to public transport, especially in trips with considerable travel times (medium and long-distance) where commuters tend to prefer the comfort and flexibility of private cars.

3.2.7. Reactions: More Options for Commuters, Less Control over Their Behaviors

Because the edition of Milan–Cortina is still in its planning stage, reactions to the planned actions are yet to be seen. However, as highlighted in Section 3.2.4 and Section 3.2.5, reactions are mostly expected to be noticed in the travel behavior of host and event commuters (especially at the interurban scale). They will result from the physical, institutional, and administrative changes in the public transport services aimed at improving connectivity between cities, reducing travel times, enhancing intermodality, and integrating information systems. However, given the wide range of possible origin/destination pairs and modal and route choices, segregation of flows might occur naturally, freeing commuters’ behaviors and complexifying forecasts.

3.2.8. Legacies: Aiming for Interconnectivity and Sustainability

Inferring from the Milan–Cortina case study, the prospective improvement of mobility at the interurban scale in Olympic regions, namely in the public transport system performance and intermodality, potentially enhances interconnectivity between host cities. The consequent expected modal shift for green modes of transport can also contribute to environmental enhancement, namely, for the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions, pollution and traffic congestion, but for that, mega-event planners need to find attractive solutions that permanently change commuters’ behaviors. However, in regard to legacy plans, the case study of Milan–Cortina remains uncertain, with many decisions scheduled only for 2022. Therefore, pros and cons of scattering venues for mobility and sustainability are still to be seen.

At last, as challenges and problems faced by Olympic regions become more diverse and edition-specific (see Section 3.2.2), extrapolations from edition to edition will become harder to realize. Nonetheless, urban regions present similarities that allow for a confident implementation of strategies that proved efficient in the past, and thus, the IOC Transfer of Knowledge program is expected to remain vital for planners.

3.3. Urban Sustainability in Olympic Regions

In contemporary urban regions, a sustainable and efficient regional mobility system is essential to mitigate undesirable migration patterns and encourage desirable ones, mitigate social polarization, promote efficient use and exploitation of resources, spatial diversity, differentiation, specialization and equity, capture investment and external income, and improve territorial cohesion and inclusion. Furthermore, time travels have important implications in the well-functioning of urban regions, impacting energy use, air pollution, and urban sprawling, thus requiring cautious consideration (especially in the context of mega-events) [56].

Driven by technological innovation in communication, transport, and accessibility, the growth of contemporary urban regions—with people moving to residential landscapes in the outskirts of cities—has also increased the scale of mobility flows [43,57]. These new centralities generate new flows of people, goods, and information, which are associated with new functions of leisure, productivity, and consumption—such as small industries, commerce, exhibition halls, hotels, restaurants, etc. [58]. However, the imbalance between the distribution of jobs and housing, and the availability of transit facilities and infrastructure is prone to lead to unsustainable land consumption and severe problems of pollution and congestion, ultimately leading to a decline in quality of life and to environmental degradation, climate change, and global warming [59]. Yet, studies have shown that low-density sprawl and polycentrism are more energy-efficient than centralized development [60]. However, while expanded urban regions might naturally promote the use of public transport, policy making needs to efficiently contribute to such a purpose, creating mixed-use environments, with a balance of jobs and residents, retail areas close to office centers, and promoting sustainable modes of transport [60,61]. In the particular case of Olympic regions, mega-event planners need to consider such issues and strive to take advantage of the event to mitigate such problems, not only increasing the Games’ sustainability but also the sustainability of resulting legacies. In this regard, smart-city and technological innovations have proven to considerably alleviate urban traffic [62], and thus, mega-event planners shall seek such innovations, possibly taking advantage of cooperation with other business partners (namely, the IOC technological partners).

The design of the venue masterplan for the Olympic Games also brings opportunities for the enhancement of urban mobility, as venues require good accessibility and functionality, and must be located in urban areas with good transport links (especially rail) [6,10]. In cases of Olympic regions, the role of public policy is to design a Games concept that adequately addresses the long-term development plans of the entire territory, potentially releasing funds for investment in needed transport infrastructure. When designing venue masterplans, mega-event planners must consider actions that promote sustainable mobility, such as mixed-used development, the choice of location for housing and facilities, as well as the proper design of public spaces [43]. The choice of cities to take part in the Games concept must take into consideration the needs of those cities for better interconnectivity and territorial cohesion. Moreover, in order to take advantage, not only of existing sports and service facilities, but also of existing and planned transport infrastructure, venue location choice and transport planning must be carried simultaneously, focalizing investment in what is deemed necessary, and avoiding the design of mobility concepts that serve only venue master plans [6].

To some degree, the case study of Milan–Cortina suggests that Olympic Agenda 2020 is being successfully implemented, namely, in ensuring that the actions carried for the Games are either temporary or act only as catalyzers of previously planned interventions, which, theoretically, facilitates the guarantee of sustainable legacies. Such success is also noticeable through the national public support of 83% in favor of the Italian candidature [52], showing that the Agenda is contributing to the mitigation of public opposition. That is especially relevant in the context of the several bid withdrawals that occurred for the Summer and Winter Olympic Games of 2020, 2022, and 2024 due to public petitions, referendums, and lack of political support in host cities [63], which included two bid withdrawals from another Italian city, Rome, for the Summer Games of 2020 and 2024. However, the alignment of investment with the host’s long-term plans is not sufficient to guarantee a sustainable legacy, as the strategies to implement such plans can negatively affect parts of the territory and population [47]. In the particular case of Milan–Cortina, the difference in the allocation of resources is noticeable between Milan and Venice and the respective west-east connections, when compared to the south-north links that connect these larger cities with the smaller and more isolated cohosting mountain areas. Thus, venue location choice in Olympic regions has to be carefully regarded to equally spread and multiply the event benefits for all involved populations.

For the organizers of Milan–Cortina 2026, to promote “sustainable development and cooperation in the macro-alpine region” is one of the five primary motivations for hosting the Olympic Games [49] (p. 4). This aspect is particularly important as international institutions and organizations, such as the United Nations and the European Union, are pursuing policies to promote territorial cohesion and polycentricity of urban regions, in which sustainable mobility plays a primary role [59,64]. Furthermore, ‘region-branding’ strategies—instead of the usual city-branding—can prove to be one of the biggest advantages of Olympic regions, as media exposure can contribute to the global promotion of the territory as a whole. However, in this regard, the branding name “Milan–Cortina 2026” seems to be inadequate to promote the entire Alpine macroregion—contrary to the branding name of the German private initiative “Rhein–Ruhr 2032”, which aimed at hosting the 2032 Summer Games in 14 cities of the Rhein–Ruhr polycentric region.

Finally, increased travel times between Olympic clusters might compromise daily round trips for participants and spectators. In Milan–Cortina, stakeholders might have to stay overnight to experience all Olympic sites [52]. Thus, it must be acknowledged that the move towards an Olympic region implies that mega-event planners must prepare the host’s transport network for an ‘Olympic Transport Relay’. Moreover, with that comes the additional challenge of guaranteeing that distances do not encourage the use of unsustainable modes of transport, such as air and private cars. It is important to recognize that the large number of travels performed by stakeholders generates environmental externalities, which are aggravated in Olympic regions where the need for mobility is higher. If not correctly tackled, these externalities might compromise the environmental sustainability of the event and of its legacy.

4. Conclusions

The challenges that planners face when preparing a city’s transport system for the Olympic Games are complex and diverse. Complexity comes from the high pressure that the host transport system is subject to, due to travels of regular commuters and time- and place-specific peaks of additional event demand. Diversity is associated with the specificities of each host city, the characteristics of each edition of the Games and the contemporary challenges that societies face at each particular time. In this research, the mobility problem at the Olympic Games was systematized and conceptualized, and a framework comprising eight knowledge dimensions that mega-event mobility planners have to consider was proposed. However, no efforts were put into validating the framework, leaving such a task for further developments that can potentially prove and improve it as a comprehensive tool to assist mega-event mobility planners and academics.

In summary, the mobility problem concerns three time periods: the planning (including the candidature and the preparation processes), the delivery, and the legacy. It is edition specific, subject to host and event characteristics, and occurs at different spatial scales, namely the international, the interurban, the intraurban, and the venue scales. Transport supply is provided by different modes of transport (air, rail, road, and soft modes) that are multi-user and function-specific for each spatial scale. Demand derives from two types of stakeholders, the city regular commuters and the event participants, requiring different provisions/priorities. Decision-making processes at the planning stage result in permanent/temporary actions meant to match supply with demand. They aim at optimizing supply through infrastructure/service improvement, decreasing demand through the elimination of trips or their dispersion in space and time, and/or controlling the equilibrium between both through efficiency monitoring, modal shift, and client segregation. These actions result in permanent/temporary reactions in the mobility system, which can be planned or unplanned. All pairs of action–reaction create legacies, which can be structural changes in territories or the generation of knowledge for policy making.

Following the implementation of Olympic Agenda 2020, several cities, regions, states, or countries will be allowed to be hosts of the Games. As its main objective, this research explored how the move towards an Olympic region can affect the mobility problem faced by mega-event planners. For such a purpose, the mobility concept of the Milan–Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics—the first Olympic region—was analyzed. The planning for this edition—currently undergoing its preparation stage—shows an increased concern for the performance of interurban transport, with planned interventions aimed at strengthening territorial interconnectivity and cohesion, increasing intermodal efficiency, and improving public transport services for medium and long distances, thus aiming at fostering modal shift. Moreover, all transport interventions were planned before the bid and seem aligned with the long-term plans of the territory.

Aimed at helping to understand a new and unexplored problematic, the results of this study, however, show some limitations, and because they derive from exploratory research, cannot yet be taken as conclusive. First, Milan–Cortina 2026 is the only case of an Olympic region, and resorting only to this case study might not be indicative of a paradigmatic change. Second, the analysis of mobility planning resorted only to candidature files, which might serve to understand the planned actions, but are not guarantees that such actions are to be fully carried out. Third, because Milan–Cortina 2026 is still in an early stage of preparation, many things can change until the actual delivery of the Games (only time will allow to fully observe the effects on mobility planning of expanding the host’s spatial scale).

Nonetheless, this study has shown that the move towards an Olympic region potentially brings several new concerns for mega-event planners. Since planned transport infrastructure interventions extend through longer links, they become increasingly expensive and subject to risks, requiring longer completion times. Involving more cities in the mobility problem also increases its diversity, raising opportunities and threats in regard to governance and equity issues. Between relatively distant cities, mobility at the interurban scale becomes particularly relevant and demand becomes spatially dispersed, which is expected to put less pressure on infrastructure capacities but increase the importance of delivering efficient transport services for medium and long distances. In this aspect, railway transport plays an increasingly important role. Moreover, ensuring a well-functioning intermodal transport system is likely to become vital to effectively change modal shift behaviors and promote more sustainable mobility, especially when impacted host populations are larger. The planned actions to solve the mobility problem in Olympic regions do not differ much in nature from the ones adopted by previous hosts, but the scale at which some of them need to be implemented significantly changes. The reactions, however, can become less predictable, as commuters are provided with several mode and route choices, which, for medium and long distances, might compromise the expected modal shift. Finally, one of the most relevant potential legacies of hosting the Games at a regional scale is the enhancement of interconnectivity and territorial cohesion of the ever-expanding contemporary urban regions, in line with the sustainability concerns of modern societies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.d.S., R.M. and M.D.; Formal analysis, S.D.V.; Investigation, G.L.d.S.; Methodology, G.L.d.S. and R.M.; Supervision, R.M.; Validation, S.D.V.; Writing–original draft, G.L.d.S.; Writing–review & editing, R.M., M.D. and S.D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia—FCT, Portugal” and funding number is “SFRH/BD/146177/2019”, which refers to Gustavo Lopes dos Santos’ PhD project “Sustainable Urban development and Mega-Events: The impacts of the Olympic Agenda 2020 in future Olympic Legacies”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bovy, P. Athens 2004 Olympic Games Transport. Str. Verkehr 2004, 7–8, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bovy, P. Solving outstanding mega-event transport challenges: The Olympic experience. Public Transp. Int. 2006, 6, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kassens-Noor, E. Sustaining the Momentum. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2187, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOC. Olympic Agenda 2020—Olympic Games: The New Norm; IOC: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Budzier, A.; Lunn, D. Regression to the tail: Why the Olympics blow up. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2021, 53, 233–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassens-Noor, E. Transport Legacy of the Olympic Games, 1992–2012. J. Urban Aff. 2012, 35, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essex, S.; Chalkley, B. Mega-sporting events in urban and regional policy: A history of the Winter Olympics. Plan. Perspect. 2004, 19, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Pitts, A. A brief historical review of Olympic urbanization. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2006, 23, 1232–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.R.; Gold, M.M. Olympic Cities: City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2016, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, D.; Dickinson, J.; Calver, S. Planning transport for special events: A conceptual framework and future agenda for research. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Delbosc, A. Assessing Travel Demand Management for the Summer Olympic Games. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2011, 2245, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovy, P. No Transport White Elephants. Siemens ITS Mag. Intell. Traffic Syst. 2010, 2, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes dos Santos, G.; Gonçalves, J. The Olympic Effect in Strategic Planning: Insights from Candidate Cities. Plan. Perspect. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]