Efficiency Analysis of Graduate Alumni Insertion into the Labor Market as a Sustainable Development Goal

Abstract

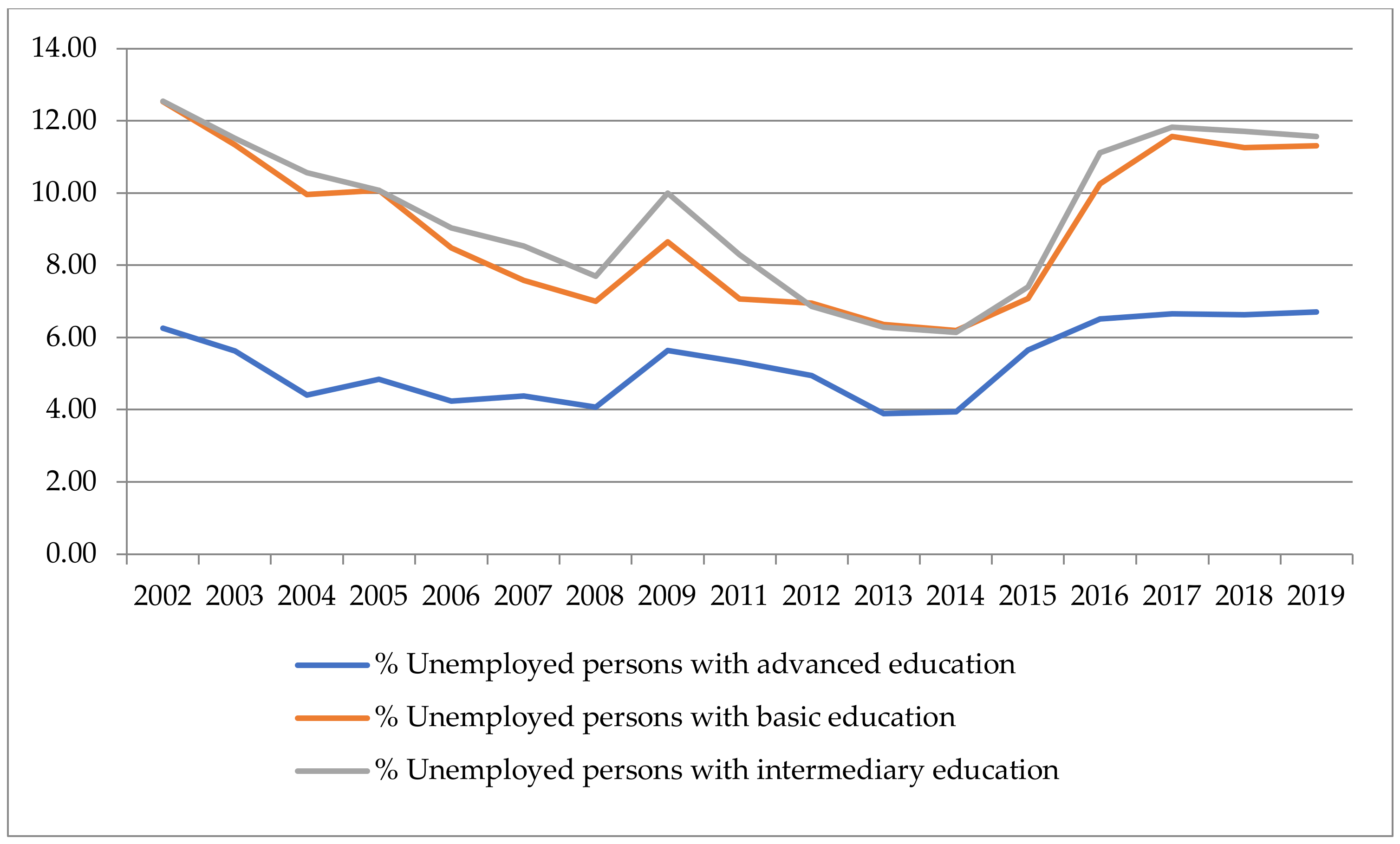

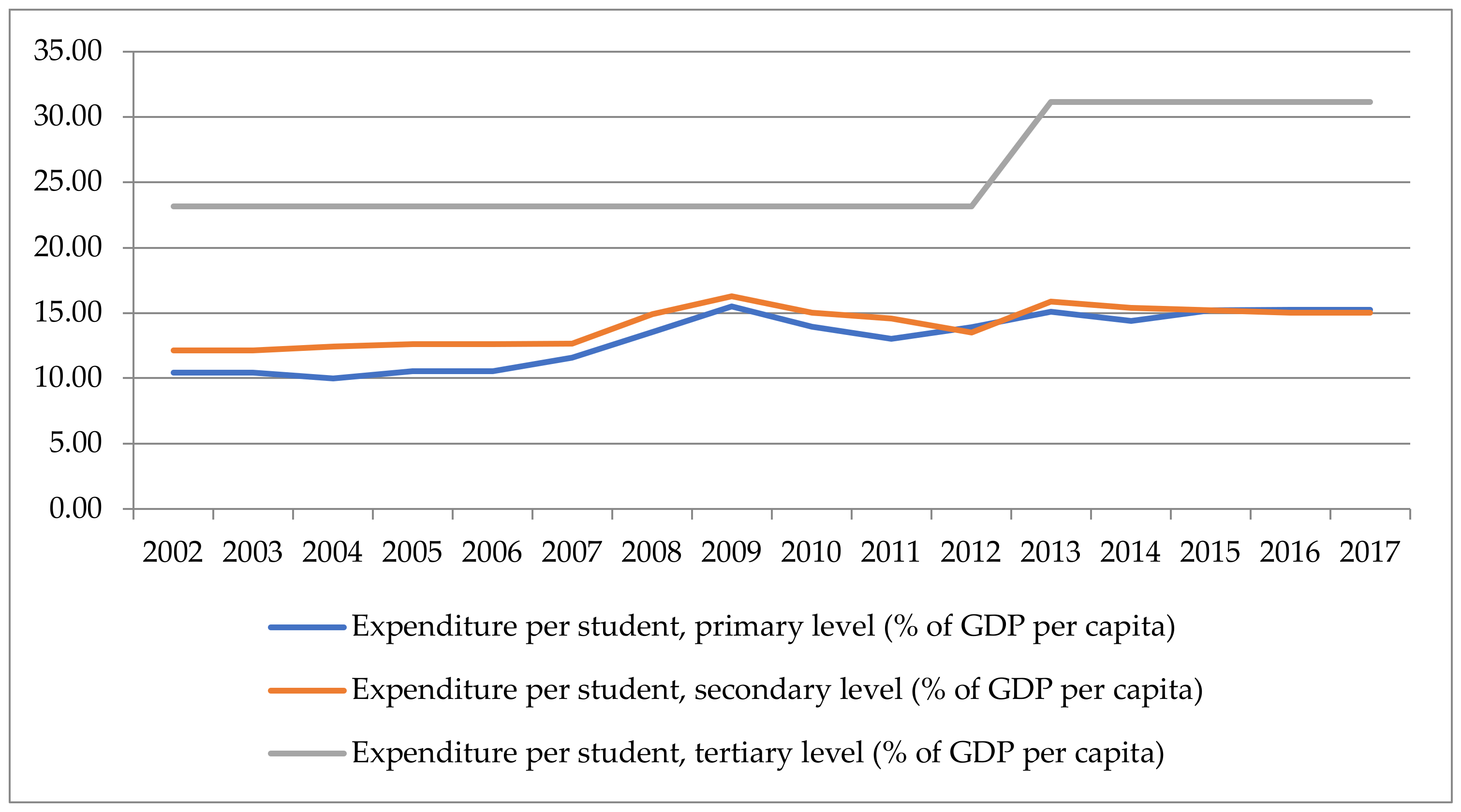

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. University Efficiency Analysis

2.2. Methodology

- Scale efficiency: the choice of the output that maximizes profit at all possible levels of production.

- Allocative efficiency: the choice of an optimal combination of inputs that minimizes production costs.

- Technical efficiency: the production of a certain level of output in which the minimum number of inputs is used.

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization (ILO). ILO: Latin America and the Caribbean Experience Slight Increase in Unemployment, Which Could Get Worse in 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/caribbean/newsroom/WCMS_735506/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Becker, G.S. Human capital revisited. In Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, P.; Mitra, D.; Ranjan, P. International trade and unemployment: Theory and cross-national evidence. J. Int. Econ. 2009, 78, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Felbermayr, G.; Prat, J.; Schmerer, H.J. Trade and unemployment: What do the data say? Eur. Econ. Rev. 2011, 55, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolós, C.B.; Gallego, M.C.; Jaén, M.D.M. The acquisition of skills for the employability of graduates. Magazine of the International Congress of University Education and Innovation (CIDUI), 2–4 July 2014; 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Algaba, M.J. Employability: New challenges in selection and training. Hum. Cap. J. Integr. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2009, 22, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Colom, M.; Peralta, P. The development of employability in the training of the tourism, hotel and gastronomic sector developed in a blended environment. In Book of Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of Educational Sciences and Development; Spanish Association of Behavioral Psychology AEPC: Granada, Spain, 2018; p. 423. [Google Scholar]

- Gillis, M.; Perkins, D.H.; Roemer, M.; Snodgrass, D.R. Economics of Development, 3rd ed.; WW Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña, O.A.E.; González, P.A.V. Education as a Motor for Integral Development: The Importance of Human Capital in Long-Term Economic and Social Growth (No. 009936); National University of Colombia-FCE-CID: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Manger, M.S.; Shadlen, K.C. Trade and Development. In The Oxford Handbook of the Political Economy of International Trade; Martin, L.L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, C.; Da Silva, J.; Monsueto, S. Objectives of Sustainable Development and Youth Employment in Colombia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birau, F.R.; Dănăcică, D.-E.; Spulbar, C.M. Social Exclusion and Labor Market Integration of People with Disabilities. A Case Study for Romania. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dincă, M.; Lucheș, D. Work Integration of the Roma: Between Family and Labor Market. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Yang, G.L. A survey and analysis of the first 40 years of scholarly literature in DEA: 1978–2016. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2018, 61, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R. La eficiencia productiva en el ámbito universitario: Aspectos claves para su evaluación. Estud. de Econ. Apl. 2007, 25, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, R.M. Productive efficiency in the university environment: Key aspects for its evaluation. Appl. Econ. Stud. 2007, 25, 793–811. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, F.G.; Capurro, A.C.; Santana, M.A.P.; Castillo, J.Q. The concept of organizational efficiency: An approach to the university. Lead. Mag. 2014, 16, 126–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gette, M.; Pordomingo, E.; Rodríguez, R.; Antonietti, L. Insercion laboral y trayectoria profesional de los contadores publicos egresados de la FCEYJ de la UNLPAM. Perspect. Cienc. Econ. Juríd. 2018, 8, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez Martín, M.M.; Morresi, S.S.; Delbianco, F. A measurement of internal efficiency in an Argentine university using the stochastic frontier method. J. High. Educ. 2017, 46, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Barquero Pérez, J.; Ruesga Benito, S. Determinant factors of the success in the labor insertion of university students: The case of Spain. Atl. Rev. Econ. 2019, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R.P.; Bastidas, G.M. Instruments for the Determination of the Factors of the Labor Insertion in University Students. Sci. J. Hallazgos 2019, 4, 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Abramo, G.; Cicero, T.; D’Angelo, C.A. A field-standardized application of DEA to national-scale research assessment of universities. J. Informetr. 2011, 5, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, Y.J.; Lu, H.; Bi, K. An AHP/DEA method for measurement of the efficiency of R&D management activities in universities. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2004, 11, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kuah, C.T.; Wong, K.Y. Efficiency assessment of universities through data envelopment analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2011, 3, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puertas, R.; Marti, L. Sustainability in universities: DEA-Greenmetric. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Afonso, A.; Santos, M. Students and Teachers: A DEA Approach to the Relative Efficiency of Portuguese Public Universities; ISEG-UTL Economics Working Paper No. 07/2005/DE/CISEP; University of Lisbon: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, D.; Costică, I.; Simionescu, L.N.; Gherghina, Ş.C. A DEA Approach towards Exploring the Sustainability of Funding in Higher Education. Empirical Evidence from Romanian Public Universities. Amfiteatru Econ. 2020, 22, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, K.H.; Prikoszovits, J.; Schaffhauser-Linzatti, M.; Stowasser, R.; Wagner, K. The impact of size and specialization on universities’ department performance: A DEA analysis applied to Austrian universities. High. Educ. 2007, 53, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Domínguez, A.; Backhouse Erazo, P.; Améstica-Rivas, L. Desertion and graduation. Measuring the efficiency of state universities in Chile. MENDIVE Educ. Mag. 2020, 18, 326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga-Martínez, F.; Fernández-Vázquez, E.; Alberto, C.L. Efficiency in public higher education on Argentina 2004–2013: Institutional decisions and university-specific effects. Lat. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visbal-Cadavid, D.; Martínez-Gómez, M.; Guijarro, F. Assessing the efficiency of public universities through DEA. A case study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres-Samuel, M.; Vásquez, C.; Viloria, A.; Borrero, T.C.; Varela, N.; Cabrera, D.; Gaitán-Angulo, M.; Lis-Gutiérrez, J.-P. Efficiency analysis of the visibility of Latin American Universities and their impact on the ranking web. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Data Mining and Big Data (DMBD 2018), Shanghai, China, 17–22 June 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Samuel, M.; Vásquez, C.L.; Luna, M.; Bucci, N.; Viloria, A.; Crissien, T.; Manosalva, J. Performance of education and research in Latin American countries through data envelopment analysis (DEA). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 170, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A. The Measurement of Efficiency and Productivity; Concept and measurement of productive efficiency; Pyramid Editions: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, M.J. The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1957, 120, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maza, F.J.; Vergara, J.C.; Navarro, J.L. Efficiency of investment in the subsidized health regime in Bolívar-Colombia. Investig. Andin. 2012, 14, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, G. Output efficiency evaluation of university human resource based on DEA. Procedia Eng. 2011, 15, 4707–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanco, M.; Bares, L.; Hrynevych, O. University Brand as a Key Factor of Graduates Employment. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2019, 3, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.B.; Lee, J.W. Comparing the efficiency of college and university employment using DEA analysis program. J. Korea Soc. Comput. Inf. 2018, 23, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Kim, W. A Statistical Analysis on Environmental Factors Affecting Education Efficiency of China’s 4-year Universities. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2018, 204, 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Data Envelopment Analysis. In Operational Research’90; Breadley, H.E., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, L.J.; Plaza, J.A. Analysis of efficiency in credit cooperatives in Spain. A methodological proposal based on data envelopment analysis (DEA). CIRIEC Mag. 2008, 63, 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, J.M. Efficiency, Productive Change and Technical Change in Spanish Banks and Savings Banks: A Non-Parametric Frontier Analysis; Institut Valencià d’Investigacions Econòmiques: Valencia, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bartual, A.M.; Garrido, R.S. Analysis of the efficiency and leadership of Spanish ports by geographical areas. J. Reg. Stud. 2011, 91, 161–184. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Inputs | Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Kuah and Wong [26] | Number of staff Number of taught course students Average students’ qualifications University expenditures (USD million) | Number of graduates from taught courses Average graduates’ results Graduation rate Graduates’ employment rate |

| Li [40] | Floor area Library collection size full-time teachers scientific research expenditure discipline level | Students’ scale six months after students graduate, the average monthly income students from when the school acquired the ability to work |

| Blanco, Bares and Hrynevich [41] | Number of national and international students enrolled in bachelor studies Number of national and international students enrolled in graduate studies National and international teaching staff related to bachelor and graduate studies | Overall score calculated for the indicator QS Graduate Employability |

| Jeong and Lee [42] | Participants in employment programs A language teacher Family economic volunteer Job target | Worker |

| Zhang and Kim [43] | Number of professors Number of students University student-professor ratio Campus scale Library area per student Annual science and technology funding | Employment rate Graduate employment competitiveness index Local advanced study rate Overseas advanced study rate |

| Variable | Weighting Factor (%) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| University reputation in labor matters | 30% | Value that employers assign to the universities that offer the most competent, innovative and effective graduates. |

| Graduate students | 25% | Number of students who have obtained the consideration of innovative, creative, wealthy, entrepreneurial, and/or philanthropic persons in the world. |

| Relations between universities and companies | 25% | This indicator has two parts. First, using Elsevier’s Scopus database to establish which universities are successfully collaborating with international companies. Second, it considers associations related to job placement that are reported by institutions and validated by the QS research team. |

| Participation of employers in university activities for employment | 10% | This indicator involves adding the number of entrepreneurs who have actively participated in a university campus in the last twelve months, allowing students the opportunity to network and obtain information on how to work in their companies. This “active presence” can take the form of participating in career fairs, organizing company presentations, or any other self-promotional activity. |

| University employment rate | 10% | Measures the proportion of graduates (excluding those who choose to continue studying or are not available for work) in full or part-time employment within 12 months of graduation. |

| Number | University | Country of Origin | Foundation Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pontifical Catholic University of Chile | Chile | 1888 |

| 2 | University of Sao Paulo | Brazil | 1934 |

| 3 | Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Studies | Mexico | 1943 |

| 4 | National Autonomous University of Mexico | Mexico | 1910 |

| 5 | University of the Andes | Colombia | 1948 |

| 6 | National University of Colombia | Colombia | 1867 |

| 7 | Adolfo Ibanez University | Chile | 1953 |

| 8 | University of Chile | Chile | 1842 |

| 9 | State University of Campinas | Brazil | 1962 |

| 10 | Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina | Argentina | 1958 |

| 11 | Pontifical Catholic University of Peru | Peru | 1917 |

| 12 | Anahuac University | Mexico | 1964 |

| 13 | Federal University of Rio de Janeiro | Brazil | 1920 |

| 14 | National Polytechnic Institute | Mexico | 1936 |

| 15 | Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico | Mexico | 1946 |

| 16 | Technological Institute of Buenos Aires | Argentina | 1959 |

| 17 | Pontifical Javeriana University | Colombia | 1623 |

| 18 | Pontifical Catholic University of Sao Paulo | Brazil | 1946 |

| 19 | Austral University | Argentina | 1991 |

| 20 | Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon | Mexico | 1933 |

| 21 | University of Antioquia | Colombia | 1803 |

| 22 | University of the Americas Puebla | Mexico | 1940 |

| 23 | University of Palermo | Argentina | 1986 |

| 24 | Rosario University | Colombia | 1653 |

| 25 | Diego Portales University | Chile | 1982 |

| 26 | Iberoamerican University | Mexico | 1943 |

| 27 | Federico Santa Maria Technical University | Chile | 1931 |

| 28 | Torcuato Di Tella University | Argentina | 1991 |

| 29 | University of Brasilia | Brazil | 1962 |

| 30 | Federal University of Minas Gerais | Brazil | 1927 |

| 31 | Federal University of São Paulo | Brazil | 1933 |

| Type | Variable | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product (Output) | (QS) Overall score | Overall score calculated for the QS Graduate Employability indicator | |

| Supplies (Inputs) | (I.1) Undergraduate students | (I.1.1) National undergraduate students | Number of students enrolled in national and foreign undergraduate studies |

| (I.1.2) International undergraduate students | |||

| (I.2) Graduate students | (I.2.1) National Graduate students | Number of students enrolled in graduate studies, both national and foreign | |

| (I.2.2) International graduate students | |||

| (I.3) Teaching staff | (I.3.1) National teaching staff | Professors who give lectures at national or foreign undergraduate and graduate programs | |

| (I.3.2) Foreign professors | |||

| Measures | QS | (I.1.1) | (I.1.2) | (I.2.1) | (I.2.2) | (I.3.1) | (I.3.2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance | 228.163928 | 734,212,950 | 216826.087 | 53,116,497.4 | 194147.661 | 7,387,006.84 | 41,942.7742 |

| Standard deviation | 15.354784 | 27,544.2683 | 473.34303 | 7408.57931 | 448.154447 | 2762.83195 | 208.184694 |

| Quasi variance | 235.769392 | 758,686,715 | 224 053.624 | 54,887,047.3 | 200,842.408 | 7,633,240.41 | 43,340.8667 |

| Median | 20.8 | 13,831.95 | 114.3 | 2833.05 | 198.28 | 1459 | 90 |

| Kurtosis coefficient | 1.85879361 | 3.7972693 | 2.51801821 | 5.17050646 | 14.183411 | 11.7251631 | 10.2494093 |

| Asymmetry coefficient | 1.6635453 | 2.01239477 | 1.68815632 | 2.23745989 | 3.43421411 | 3.13510568 | 3.18941097 |

| Maximum | 73.6 | 113,551.2 | 1731.38 | 30,222.46 | 2351.24 | 14124 | 949 |

| Minimum | 20.8 | 1448.18 | 0 | 459.2 | 0 | 146 | 0 |

| Ranking | 52.8 | 112,103.02 | 1731.38 | 29,763.26 | 2351.24 | 13,978 | 949 |

| Group Number | University | Score | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iberoamerican University | 100 | 0 |

| Torcuato Di Tella University | 100 | 0 | |

| Adolfo Ibanez University | 100 | 0 | |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina | 100 | 0 | |

| Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Studies | 100 | 0 | |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Chile | 100 | 0 | |

| 2 | University of the Andes | 98.41 | 1.59 |

| Technological Institute of Buenos Aires | 92.5 | 7.5 | |

| University of Sao Paulo | 90.08 | 9.92 | |

| 3 | Austral University | 86.38 | 13.62 |

| University of the Americas Puebla | 86.21 | 13.79 | |

| Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico | 83.81 | 16.19 | |

| Federico Santa María Technical University | 81.66 | 18.34 | |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Sao Paulo | 80.17 | 19.83 | |

| 4 | Rosario University | 76.62 | 23.38 |

| Pontifical Catholic University of Peru | 76.43 | 23.57 | |

| Anahuac University | 70.45 | 29.55 | |

| 5 | National Autonomous University of Mexico | 69.29 | 30.71 |

| State University of Campinas | 68.45 | 31.55 | |

| National university of Colombia | 64.98 | 35.02 | |

| University of Chile | 60.62 | 39.38 | |

| 6 | Federal University of Sao Paulo | 56.29 | 43.71 |

| University of Palermo | 53.55 | 46.45 | |

| 7 | University of Antioquia | 49.35 | 50.65 |

| Federal University of Rio de Janeiro | 47.37 | 52.63 | |

| Diego Portales University | 45.11 | 54.89 | |

| Pontifical Javeriana University | 44.27 | 55.73 | |

| Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon | 41.83 | 58.17 | |

| 8 | National Polytechnic Institute | 34.22 | 65.78 |

| Federal University of Minas Gerais | 33.26 | 66.74 | |

| University of Brasilia | 29.41 | 70.59 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blanco, M.; Bares, L.; Ferasso, M. Efficiency Analysis of Graduate Alumni Insertion into the Labor Market as a Sustainable Development Goal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020842

Blanco M, Bares L, Ferasso M. Efficiency Analysis of Graduate Alumni Insertion into the Labor Market as a Sustainable Development Goal. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020842

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlanco, Miguel, Lydia Bares, and Marcos Ferasso. 2022. "Efficiency Analysis of Graduate Alumni Insertion into the Labor Market as a Sustainable Development Goal" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020842

APA StyleBlanco, M., Bares, L., & Ferasso, M. (2022). Efficiency Analysis of Graduate Alumni Insertion into the Labor Market as a Sustainable Development Goal. Sustainability, 14(2), 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020842