Falling Apart and Coming Together: How Public Perceptions of Leadership Change in Response to Natural Disasters vs. Health Crises

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Leadership for the Greater Good

2.1.1. Outcomes

2.1.2. Trust and Legitimacy

2.1.3. Responsiveness and Balance

2.2. Perceptions of Leadership in Times of Crisis

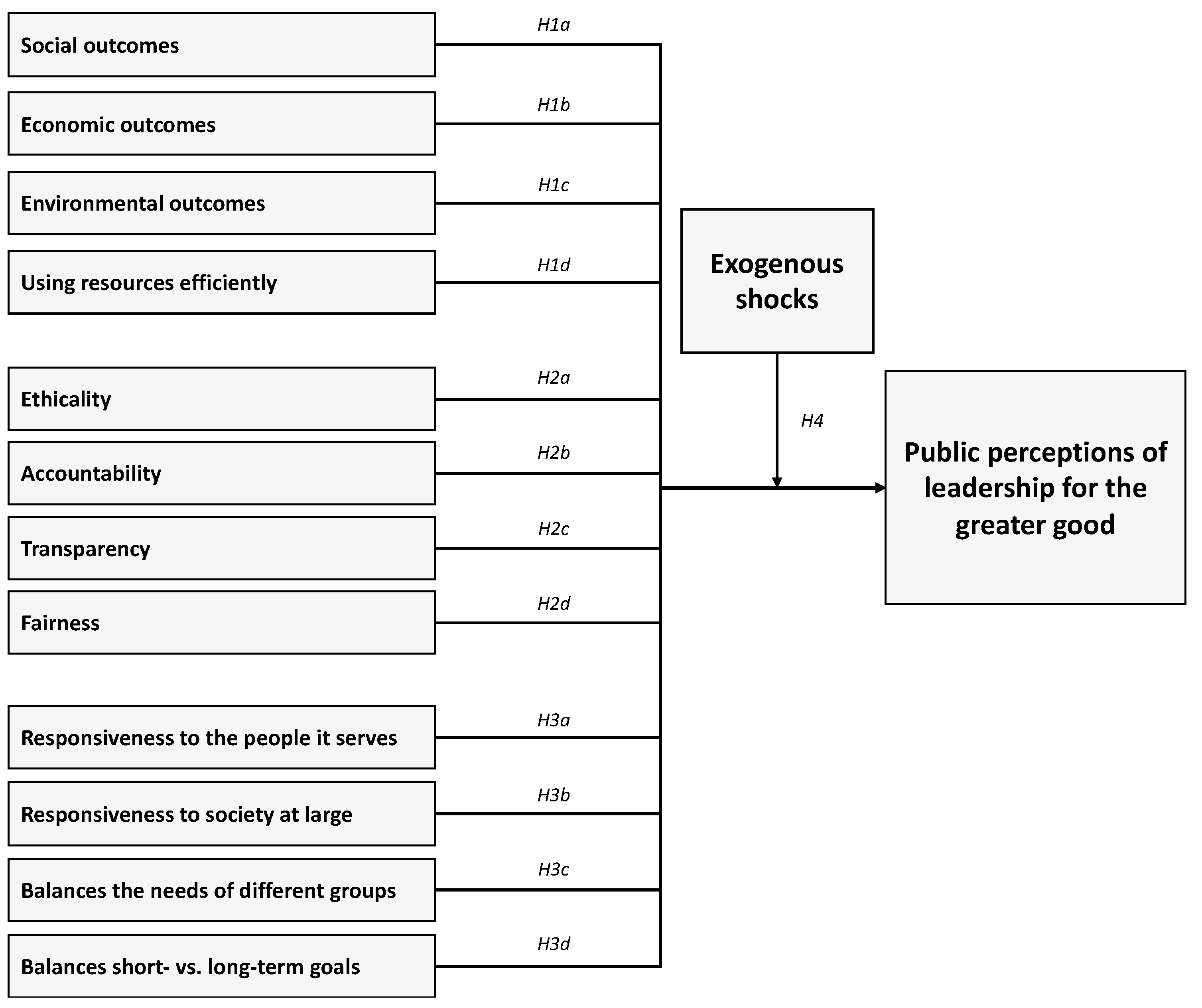

Exogenous Shocks

2.3. Overview of Study

3. Method

3.1. Scale Development

3.2. Participants and Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

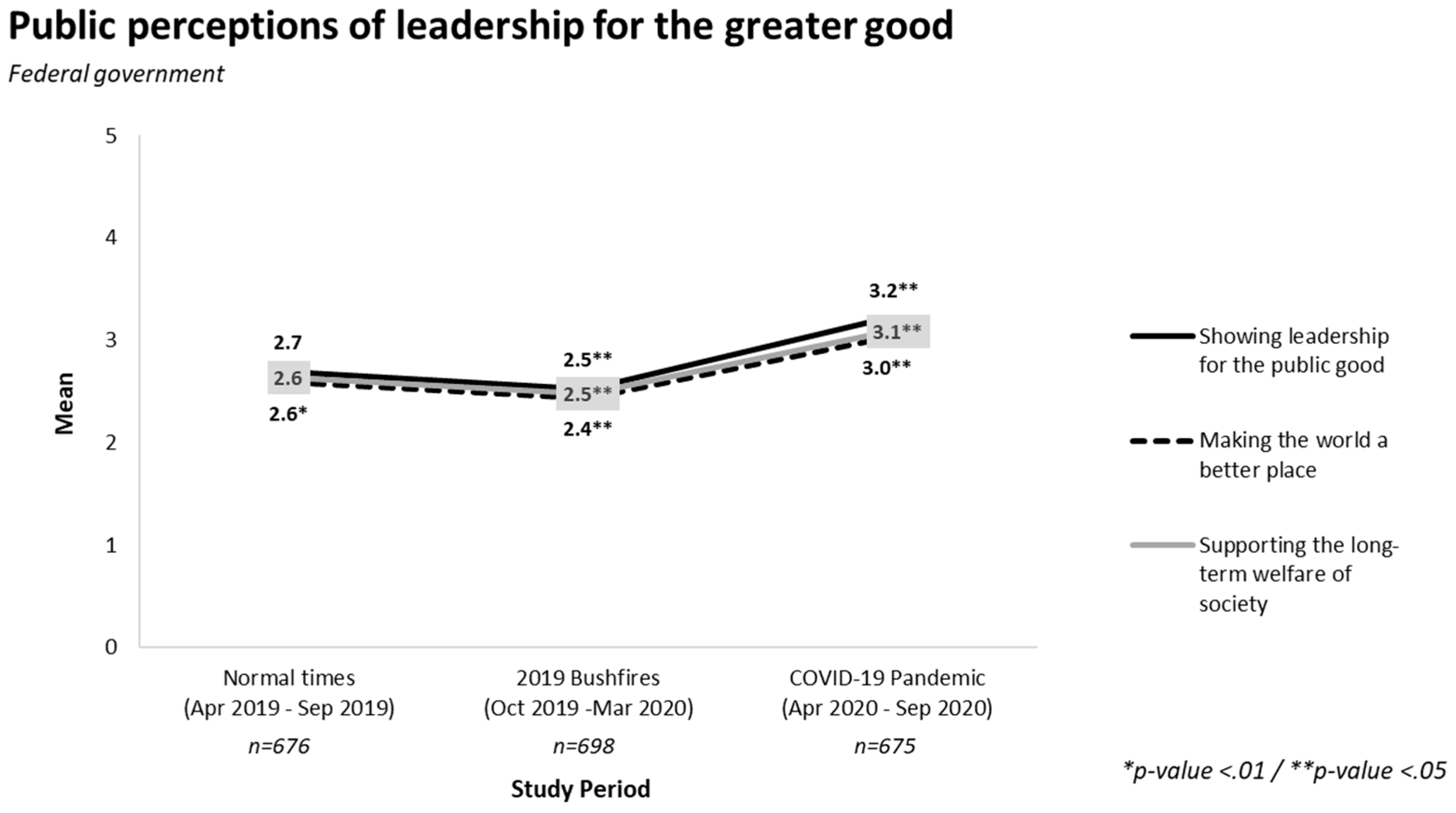

4.2. Longitudinal Analysis

4.3. Test of Formative Measurement Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Perceptions of Leadership in Times of Crisis

5.2. Drivers of Leadership Perceptions

5.3. Theoretical Contribution

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Applications for Leaders and Conclusions

7.1. Practical Implications

7.2. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M. Responsible Leadership in a Stakeholder Society—A Relational Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pless, N.M.; Sengupta, A.; Wheeler, M.A.; Maak, T. Responsible Leadership and the Reflective CEO: Resolving Stakeholder Conflict by Imagining What Could be Done. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.A. Responsible Leadership. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Leadership Studies; Goethals, G.R., Allison, S.T., Sorenson, G.J., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, in press.

- Benn, S.; Dunphy, D.; Griffiths, A. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bodolica, V.; Spraggon, M. An Examination into the Disclosure, Structure, and Contents of Ethical Codes in Publicly Listed Acquiring Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; t’Hart, P.T. Public Leadership in Times of Crisis: Mission Impossible? Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Kuipers, S.; Overdijk, W. Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Framework for Assessment. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 18, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boin, A.; Hart, P.; Kuipers, S. The Crisis Approach. In Handbook of Disaster Research. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu, N.; Van Wart, M. Making Matters Worse: An Anatomy of Leadership Failures in Managing Catastrophic Events. Adm. Soc. 2008, 40, 711–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohrstedt, D.; Bynander, F.; Parker, C.; t Hart, P. Managing Crises Collaboratively: Prospects and Problems—A Systematic Literature Review. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2018, 1, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, S.G.; Gray, S.; Bednall, T.; Pallant, J.; Wheeler, M.; Demsar, V. Australian Leadership Index: 2020 National Survey Report; Swinburne University of Technology: Melbourne, Australia; Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/310712 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Wilson, S.; Pallant, J.; Bednall, T.; Gray, S. Australian Leadership Index: 2019 National Survey Report; Swinburne University of Technology: Melbourne, Australia. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/306040 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Brookes, S.; Grint, K. A New Public Leadership Challenge? In The New Public Leadership Challenge; Brookes, S., Grint, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.H. Recognizing Public Value; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, R.S. Integrative public leadership: Catalyzing collaboration to create public value. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J. Whose Interests? Why Defining the ‘Public Interest’ Is Such a Challenge. The Conversation, 22 September 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/whose-interests-why-defining-the-public-interest-is-such-a-challenge-84278 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Wilson, S.G. Leadership for the Common Good. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Leadership Studies; Goethals, G.R., Allison, S.T., Sorenson, G.J., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, in press.

- Sluga, H. Politics and the Search for the Common Good; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C. Leadership for the Common Good: Tackling Public Problems in a Shared-Power World; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, B.C.; Bryson, J.M. Special issue on public integrative leadership: Multiple turns of the kaleidoscope. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.; Crosby, B.; Stone, M.M. The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, L. What do we Expect of Public Leaders? In The New Public Leadership Challenge; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, N.; Kaufman, S. Avoiding Theoretical Stagnation: A Systematic Review and Framework for Measuring Public Value. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebble, M. Public Value and the Ideal State: Rescuing Public Value from Ambiguity. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2012, 71, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.; Wanna, J. The Limits to Public Value, or Rescuing Responsible Government from the Platonic Guardians. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2007, 66, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, C. Paradoxes and Prospects of ‘Public Value’. Public Money Manag. 2011, 31, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman. 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/trust/2021-trust-barometer (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Kempster, S.; Carroll, B. Introduction: Responsible Leadership-Realism and Romanticism. In Responsible Leadership-Realism and Romanticism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Miska, C.; Mendenhall, M.E. Responsible Leadership: A Mapping of Extant Research and Future Directions. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T.; Waldman, D.A. Different approaches toward doing the right thing: Mapping the responsibility orientations of leaders. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, S.; Parry, K.; Maak, T. Leadership of Purpose: In Search of Good Dividends. In Good Dividends: Responsible Leadership of Business Purpose; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Haksever, C.; Chaganti, R.; Cook, R.G. A Model of Value Creation: Strategic View. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 49, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooten, L.P.; James, E.H. Linking crisis management and leadership competencies: The role of human resource development. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2008, 10, 352–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozacik, S.M. Crisis communications for boards and executives. Corp. Board 2003, 24, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger, M.W.; Ulmer, R.R.; Novak, J.M.; Sellnow, T. Post-crisis discourse and organizational change, failure and renewal. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2005, 18, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovski, D. Management mistakes as causes of corporate crises: Managerial implications for countries in transition. Total Qual. Manag. 2009, 20, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaques, T. Crisis leadership: A view from the executive suite. J. Public Aff. 2012, 12, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalshoven, K.; Den Hartog, D.N.; De Hoogh, A.H.B. Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Pless, N.M.; Maak, T. Development of a Scale Measuring Discursive Responsible Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douglas, B.; Wodak, J. Foreword: Defining and defending the public interest in Australia. In Who Speaks for and Protects the Public Interest in Australia? Essays by notable Australians; Douglas, B., Wodak, J., Eds.; Australia21: Weston, ACT, Australia, 2015; pp. 2–3. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/237506 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus. In Handbook of Item Response Theory: Volume 3: Applications; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Riefler, P.; Roth, K.P. Advancing Formative Measurement Models. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smee, B. Like Nothing We’ve Seen: Queensland Bushfires Tear through Rainforest. The Guardian Australia, 9 September 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/sep/09/like-nothing-weve-seen-queensland-bushfires-tear-through-rainforest (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Chapman, A. NSW State of Emergency Declared While Bushfires Also Burn in Queensland, South Australia and WA. 7news Australia, 12 November 2019. Available online: https://7news.com.au/news/bushfires/nsw-state-of-emergency-declared-while-bushfires-also-burn-in-queensland-south-australia-and-wa-c-551562 (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Zhou, N. Former Australian Fire Chiefs Say Coalition Ignored Their Advice Because of Climate Change Politics. The Guardian Australia, 13 November 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/nov/14/former-australian-fire-chiefs-say-coalition-doesnt-like-talking-about-climate-change (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Stanley, J. Why Is the Government Refusing to Link Bushfires to Climate Change? The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November 2019. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/national/why-is-the-government-refusing-to-link-bushfires-to-climate-change-20191113-p53a7l.html (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Thomas, T.; Wilson, A.; Tonkin, E.; Miller, E.R.; Ward, P.R. How the Media Places Responsibility for the COVID-19 Pandemic–An Australian Media Analysis. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkington, J. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, R.S.; Buss, T.F.; Kinghorn, C.M. Transforming Public Leadership for the 21st Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kempster, S.; Maak, T.; Parry, K. The Good Dividends: A Systemic Framework of Value Creation. In Good Dividends: Responsible Leadership of Business Purpose; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, D.R.; Hoyt, C.L. For the Greater Good of All: Perspectives on Individualism, Society, and Leadership; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques-Gomes, L. Robodebt: Court Approves $1.8 bn Settlement for Victims of Governments Shameful Failure. The Guardian. 2021. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jun/11/robodebt-court-approves-18bn-settlement-for-victims-of-governments-shameful-failure (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Villela, M.; Bulgacov, S.; Morgan, G. B Corp certification and its impact on organizations over time. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 170, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Model | χ² | DF | p | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Factor | 801.779 | 90 | 0.000 | 0.913 | 0.119 | 0.041 | 18,530.806 |

| 2 Factor EFA | 228.525 | 76 | 0.000 | 0.981 | 0.060 | 0.017 | 18,046.219 |

| 3 Factor EFA | 111.195 | 63 | 0.000 | 0.994 | 0.037 | 0.011 | 18,011.221 |

| 4 Factor EFA | 83.730 | 51 | 0.000 | 0.996 | 0.034 | 0.008 | 18,059.755 |

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.46 *** (0.04) | 0.47 *** (0.04) | 0.48 *** (0.05) |

| focused on creating positive social outcomes | 0.09 *** (0.02) | 0.09 *** (0.02) | 0.11 ** (0.03) |

| focused on creating positive economic outcomes | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.04 (0.02) |

| focused on creating positive environmental outcomes | 0.05 ** (0.02) | 0.07 ** (0.02) | 0.06 * (0.03) |

| transparent | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.03) |

| demonstrating high ethical standards | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.12 *** (0.03) |

| be accountable for their actions | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.11 *** (0.03) |

| be responsive to society’s needs | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.11 *** (0.02) | 0.14 *** (0.03) |

| responsive to the people it serves | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.10 ** (0.03) |

| balancing the needs of different groups | 0.05 * (0.02) | 0.05 * (0.02) | 0.01 (0.03) |

| balancing long-term and short-term goals | 0.09 *** (0.02) | 0.09 *** (0.02) | 0.10 ** (0.03) |

| using resources efficiently | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.03) |

| treating people fairly | 0.08 *** (0.02) | 0.08 *** (0.02) | 0.09 ** (0.03) |

| Bushfires (main effect) | −0.07 * (0.03) | −0.07 (0.10) | |

| COVID (main effect) | 0.19 *** (0.03) | 0.15 (0.11) | |

| Bushfires × focused on creating positive social outcomes | −0.04 (0.06) | ||

| Bushfires × focused on creating positive economic outcomes | 0.03 (0.04) | ||

| Bushfires × focused on creating positive environmental outcomes | 0.02 (0.05) | ||

| Bushfires × transparent | −0.06 (0.05) | ||

| Bushfires × demonstrating high ethical standards | −0.04 (0.06) | ||

| Bushfires × be accountable for their actions | 0.02 (0.05) | ||

| Bushfires × be responsive to society’s needs | −0.04 (0.06) | ||

| Bushfires × responsive to the people it serves | 0.03 (0.06) | ||

| Bushfires × balancing the needs of different groups | 0.10 (0.05) | ||

| Bushfires × balancing long-term and short-term goals | 0.04 (0.05) | ||

| Bushfires × using resources efficiently | −0.01 (0.05) | ||

| Bushfires × treating people fairly | −0.06 (0.06) | ||

| COVID × focused on creating positive social outcomes | −0.01 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × focused on creating positive economic outcomes | 0.00 (0.04) | ||

| COVID × focused on creating positive environmental outcomes | 0.00 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × transparent | −0.02 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × demonstrating high ethical standards | 0.02 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × be accountable for their actions | 0.01 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × be responsive to society’s needs | −0.05 (0.06) | ||

| COVID × responsive to the people it serves | 0.06 (0.06) | ||

| COVID × balancing the needs of different groups | 0.07 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × balancing long-term and short-term goals | −0.07 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × using resources efficiently | 0.00 (0.05) | ||

| COVID × treating people fairly | 0.02 (0.05) | ||

| R² | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wheeler, M.A.; Bednall, T.; Demsar, V.; Wilson, S.G. Falling Apart and Coming Together: How Public Perceptions of Leadership Change in Response to Natural Disasters vs. Health Crises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020837

Wheeler MA, Bednall T, Demsar V, Wilson SG. Falling Apart and Coming Together: How Public Perceptions of Leadership Change in Response to Natural Disasters vs. Health Crises. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020837

Chicago/Turabian StyleWheeler, Melissa A., Timothy Bednall, Vlad Demsar, and Samuel G. Wilson. 2022. "Falling Apart and Coming Together: How Public Perceptions of Leadership Change in Response to Natural Disasters vs. Health Crises" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020837

APA StyleWheeler, M. A., Bednall, T., Demsar, V., & Wilson, S. G. (2022). Falling Apart and Coming Together: How Public Perceptions of Leadership Change in Response to Natural Disasters vs. Health Crises. Sustainability, 14(2), 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020837