Determining the Level of Market Concentration in the Construction Sector—Case of Application of the HHI Index

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Which index would be the best suited to assess the balance of market power in the construction market?

- What are the main approaches of competition assessment in distorted markets?

- What are advantages and disadvantages of the HHI for the use in the construction sector?

- Is DEMATEL method suitable for determining the level of market concen-tration in the construction sector?

2. The Structural Approach of Market Competition

2.1. Rosenbluth Index

2.2. Maurel–Sedillot Index

2.3. Industrial Concentration Index

2.4. Hannah and Kay Index

2.5. Hause Index

2.6. Entropy Index

2.7. HHI Index

3. Methods and Data

- (1)

- Qualification—manager of a construction company.

- (2)

- At least 10 years of experience in the construction sector.

- (3)

- Experience in conditions of distorted market competition in the construction sector.

- DEMATEL method is appropriate for assessing the competitive position of a business entity.

- HHI index is suitable for determining the competitive position, considering the specificities of the construction sector.

- The HHI index affect the ability of the business entity to avoid market distortions in relation to competitors over time.

4. Results

- -

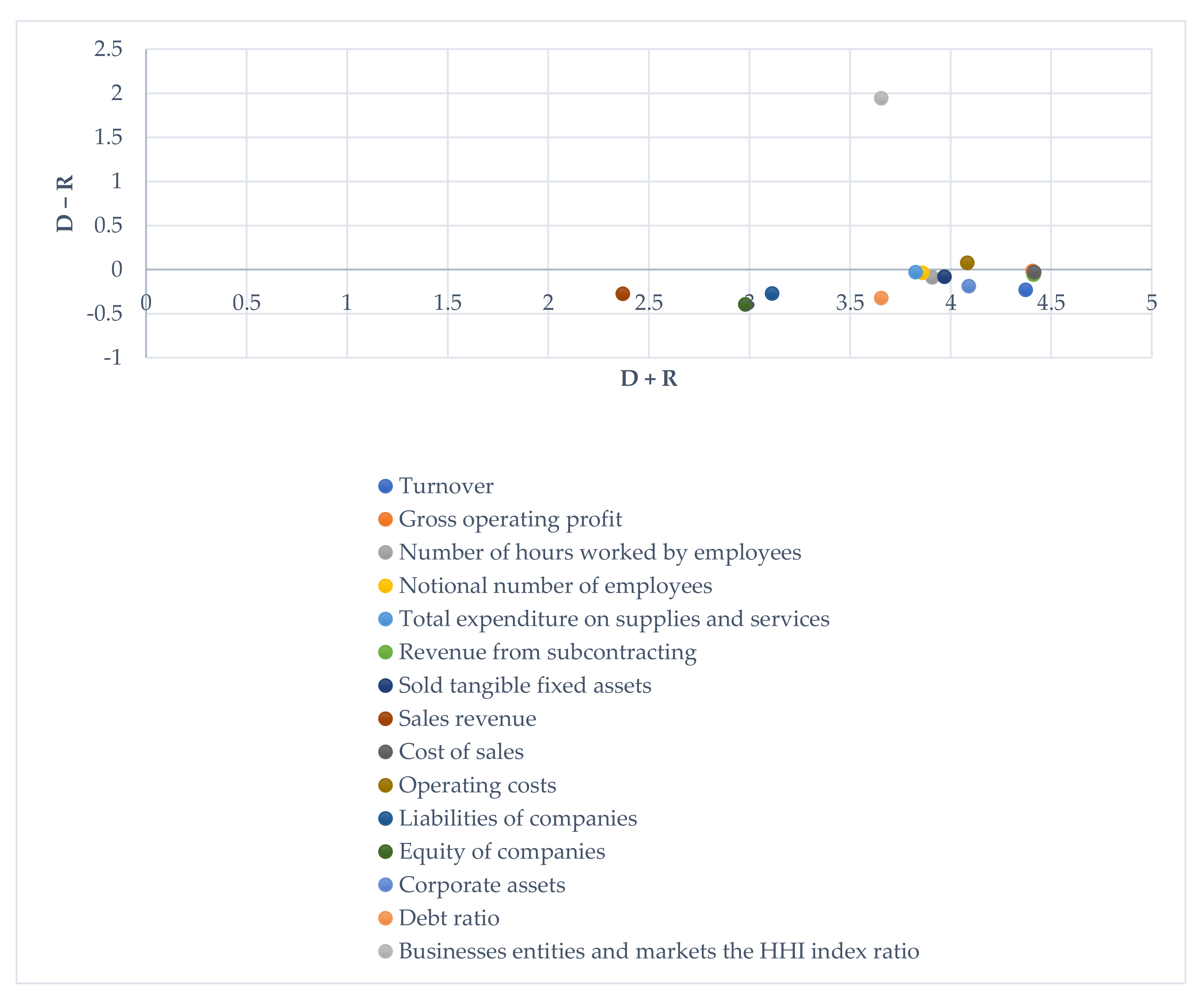

- D + R shows the level of importance between parameters, which works in the whole system. D + R shows both scores i’s impact on the entire system and influence of other system factors’ on the score in terms of importance degree. Cost of sales is ranked in the first place and next are ranked Revenue from subcontracting, Gross operating profit, Turnover, Corporate assets, Operating costs, Sold tangible fixed assets, Number of hours worked by employees, Notional number of employees, Total expenditure on supplies and services, Businesses entities and markets the HHI index ratio, Debt ratio, Liabilities of companies, Equity of companies and Sales revenue.

- -

- D − R shows the degree of a score’s impact on system. In general, the positive value of D − R represents a causal variable, and the negative value of D − R represents an effect. In this study Operating costs, Businesses entities and markets, HHI index ratio are regarded as causal variables. Turnover, Gross operating profit, Number of hours worked by employees, Notional number of employees, Total expenditure on supplies and services, Revenue from subcontracting, sold tangible fixed assets, Sales revenue, Cost of sales, Liabilities of companies, Equity of companies, corporate assets, Debt ratio are regarded as an effect.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amir, R.; Machowska, D.; Troege, M. Advertising patterns in a dynamic oligopolistic growing market with decay. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2021, 131, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androniceanu, A.; Caplescu, R.D.; Tvaronavičienė, M.; Cosmin, D. The interdependencies between economic growth, energy consumption and pollution in Europe. Energies 2021, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wisuttisak, P.; Kim, C.; Rahim, M. PPPs and challenges for competition law and policy in ASEAN. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 71, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Kliestik, T.; Novak, A. Internet of Things Smart Devices, Industrial Artificial Intelligence, and Real-Time Sensor Networks in Sustainable Cyber-Physical Production Systems. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2021, 9, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, E.; Stan, C.I.; Luțan, A.G.; Oașa, R.Ș. Internet of Things-based Real-Time Production Logistics, Sustainable Industrial Value Creation, and Artificial Intelligence-driven Big Data Analytics in Cyber-Physical Smart Manufacturing Systems. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2021, 16, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, D.; Kabir, M.; Oliver, B. Does exposure to product market competition influence insider trading profitability? J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradūnas, V.; Mikelionytė, D.; Petrauskaitė, L. Lietuvos Duonos Rinkos Koncentracijos Poveikio Kainoms Ekonominis Vertinimas: Mokslo Studija; Lietuvos Agrarinės Ekonomikos Institutas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2010; Available online: http://www.laei.lt/?mt=leidiniai&straipsnis=329&metai=2010 (accessed on 1 October 2021). (In Lithuanian)

- Maurel, F.; Sédillot, B. A measure of the geographic concentration in french manufacturing industries. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1999, 29, 575–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate for Financial And Enterprise Affairs Competition Committee. Market Definition; DAF/COMP (2012)13/REV1; Directorate for Financial And Enterprise Affairs Competition Committee: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gancevskaitė, K. Research of Competition in Lithuanian Life Insurance Market. Master’s Thesis, Vytauto Didžiojo Universitetas, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2008. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12259/124545 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Valaskova, K.; Ward, P.; Svabova, L. Deep Learning-assisted Smart Process Planning, Cognitive Automation, and Industrial Big Data Analytics in Sustainable Cyber-Physical Production Systems. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2021, 9, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loertscher, S.; Marx, L. Digital monopolies: Privacy protection or price regulation? Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2020, 71, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, W.; Kaboski, J. Exploitation of labor? Classical monopsony power and labor’s share. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 150, 102627. [Google Scholar]

- Branger, N.; Flacke, R.; Gräber, N. Monopoly power in the oil market and the macroeconomy. Energy Econ. 2020, 85, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhang, L. A new measurement of sectoral concentration of credit portfolios. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 17, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Chernenko, N. Market power issues in the reformed Russian electricity supply industry. Energy Econ. 2015, 50, 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Chileshe, M.P. Bank Competition and Financial System Stability in a Developing Economy: Does Bank Capitalization and Size Matter? BoZWorking Paper 5/2017; Bank of Zambia: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2017; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni--muenchen.de/82758/1/MPRA_paper_82758.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2019).

- Chortareas, G.; Noikokyris, E. Investment, firm-specific uncertainty, and market power in South Africa. Econ. Model. 2021, 96, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, S. Competition in the Financial Sector: Overview of Competition Policies; IMFWorking Paper; International Monetary Fund: Bali, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, J.; Cai, X.; Gautier, P.; Vroman, S. Multiple applications, competing mechanisms, and market power. J. Econ. Theory 2020, 190, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhou, C.; Lyu, G. Government subsidies for preventing supply disruption when the supplier has an outside option under competition. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 147, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Villaverde, J.; Mandelman, F.; Yu, Y.; Zanetti, F. The “Matthew effect” and market concentration: Search complementarities and monopsony power. J. Monet. Econ. 2021, 121, 62–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y. The side with larger network externality should be targeted aggressively? Monopoly pricing, reference price and two-sided competition. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 147, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guissoni, L.; Rodrigues, J.; Zambaldi, F. Distribution effectiveness through full- and self-service channels under economic fluctuations in an emerging market. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 545–560. [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah, D.; Siganos, A.; Veld, C. Effects of financial constraints and product market competition on share repurchases. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2021, 74, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, E.; Stehel, V. Internet of Things Sensing Networks, Artificial Intelligence-based Decision-Making Algorithms, and Real-Time Process Monitoring in Sustainable Industry 4.0. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2021, 9, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacova, M.; Lăzăroiu, G. Sustainable Organizational Performance, Cyber-Physical Production Networks, and Deep Learning-assisted Smart Process Planning in Industry 4.0-based Manufacturing Systems. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2021, 16, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirche, M.; Farris, P.; Greenacre, L.; Quan, Y.; Wei, S. Predicting Under - and Overperforming SKUs within the Distribution–Market Share Relationship. J.Retail. 2021, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Qian, L. Buy, lease, or share? Consumer preferences for innovative business models in the market for electric vehicles. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120639. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, M.; Liu, P. The browser war—Analysis of Markov Perfect Equilibrium in markets with dynamic demand effects. J. Econom. 2021, 222, 244–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Rhee, B. Retailer-run resale market and supply chain coordination. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108089. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.; Duan, Y.; Yao, Y.; Huo, J. The moderating effect of average wage and number of stores on private label market share: A hierarchical linear model analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102454. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Carvalho, M. Dynamic decision making in a mixed market under cooperation: Towards sustainability. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 241, 108270. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, A.; Bennett, D.; Kliestik, T. Product Decision-Making Information Systems, Real-Time Sensor Networks, and Artificial Intelligence-driven Big Data Analytics in Sustainable Industry 4.0. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2021, 16, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Subramanian, A. Search, product market competition and CEO pay. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, R.F.; Hollis, A.; Kesselheim, A.; Spackman, E. Reimagining Pharmaceutical Market Exclusivities: Should the Duration of Guaranteed Monopoly Periods Be Value Based? Value Health 2021, 24, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussawi, C.; Mansour, R. Competition, cost efficiency and stability of banks in the MENA region. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 82, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayoonrattana, J.; Laosuthi, T.; Chaivichayachat, B. Empirical Measurement of Competition in the Thai Banking Industry. Economies 2020, 8, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, R.; Prakash, V.; Ab-Rahim, R.; Selvarajan, S.K. Financial Development, Eciency, and Competition of ASEAN Banking Market. Asia-Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 19, 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Schøne, P.; Strøm, M. International labor market competition and wives’ labor supply responses. Labour Econ. 2021, 70, 101983. [Google Scholar]

- Gehlot, M.; Shrivastava, S. Sustainable construction Practices: A perspective view of Indian construction industry professionals. Mater.Today Proc. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmakinde, O.; Egbelakin, T.; Sher, W. Contributions of the circular economy to the UN sustainable development goals through sustainable construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 178, 106023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Bruni, L.; Zamagni, S. Non-competitive markets and elements of game theory. In The Microeconomics of Wellbeing and Sustainability; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 157–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, W.; Song, H.; Li, R.; Hao, J. Toward the construction of a circular economy eco-city: An emergy-based sustainability evaluation of Rizhao city in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Zhong, X. Prospect theory and stock returns: Evidence from foreign share markets. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2021, 69, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcysiak, A.; Pleskacz, Ż. Determinants of digitization in SMEs. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2021, 9, 300–318. [Google Scholar]

- Shevyakova, A.; Munsh, E.; Arystan, M.; Petrenko, Y. Competence development for Industry 4.0: Qualification requirements and solutions. Insights Reg. Dev. 2021, 3, 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Construction Statistics—Supply, Transformation, Consumption. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database?p_p_id=NavTreeportletprod_WAR_NavTreeportletprod_INSTANCE_nPqeVbPXRmWQ&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=pop_up&p_p_mode=view&_NavTreeportletprod_WAR_NavTreeportletprod_INSTANCE_nPqeVbPXRmWQ_nodeInfoService=true&nodeId=-2625 (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Hasan, D. HHI-based evaluation of the European banking sector using an integrated fuzzy approach. Kybernetes Int. J. Syst. Cybern. 2019, 48, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, G.; Opricovic, S. Defuzzification within a multicriteria decision model. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl.-Based Syst. 2003, 11, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Ruan, J. Analyzing Barriers for Developing a Sustainable Circular Economy in Agriculture in China Using Grey-DEMATEL Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Han, L. Does Income Diversification Benefit the Sustainable Development of Chinese Listed Banks? Analysis Based on Entropy and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index. Entropy 2018, 20, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.-K.; Nalluri, V.; Hung, H.-C.; Chang, M.-C.; Lin, C.-T. Apply DEMATEL to Analyzing Key Barriers to Implementing the Circular Economy: An Application for the Textile Sector. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Ou, S.-L.; Hsu, L.-C. A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model for Evaluating Companies’ Green Credit Rating. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Ratio | Ration Range | Ratio Form |

|---|---|---|

| Lerner Index | 0 = L = 1 | |

| The k concentration ratio | ||

| Gini Coefficient | 0 = G = 1 | |

| The Herfindahl Hirschman Index | ||

| The Hall-Tideman Index | ||

| The Rosenbluth Index | 1/(2C) | |

| The comprehensive industrial concentration index | ||

| The Hannah and Kay Index | ||

| The U Index | ||

| The Hause Index | ||

| Entropy Measure |

| Turnover | Gross Operating Profit | Number of Hours Worked by Employees | Notional Number of Employees | Total Expenditure on Supplies and Services | Revenue from Subcontracting | Sold Tangible Fixed Assets | Sales Revenue | Cost of Sales | Operating Costs | Liabilities of Companies | Equity of Companies | Corporate Assets | Debt Ratio | HHI Index Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.21 |

| Gross operating profit | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.2 |

| Number of hours worked by employees | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.2 |

| Notional number of employees | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.18 |

| Total expenditure on supplies and services | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.18 |

| Revenue from subcontracting | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.2 |

| Sold tangible fixed assets | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.2 |

| Sales revenue | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.17 |

| Cost of sales | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.2 |

| Operating costs | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| Liabilities of companies | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| Equity of companies | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.2 |

| Corporate assets | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| Debt ratio | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.21 |

| HHI index ratio | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Turnover | Gross Operating Profit | Number of Hours Worked by Employees | Notional Number of Employees | Total Expenditure on Supplies and Services | Revenue from Subcontracting | Sold Tangible Fixed Assets | Sales Revenue | Cost of Sales | Operating Costs | Liabilities of Companies | Equity of Companies | Corporate Assets | Debt Ratio | HHI Index Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Gross operating profit | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Number of hours worked by employees | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Notional number of employees | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total expenditure on supplies and services | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Revenue from subcontracting | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Sold tangible fixed assets | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sales revenue | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cost of sales | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Operating costs | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Liabilities of companies | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Equity of companies | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Corporate assets | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| Debt ratio | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| HHI index ratio | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| R | D | D + R | D − R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover | 2.301 | 2.072 | 4.373 | −0.23 |

| Gross operating profit | 2.212 | 2.195 | 4.407 | −0.016 |

| Number of hours worked by employees | 1.999 | 1.91 | 3.909 | −0.089 |

| Notional number of employees | 1.947 | 1.912 | 3.859 | −0.035 |

| Total expenditure on supplies and services | 1.928 | 1.898 | 3.826 | −0.03 |

| Revenue from subcontracting | 2.234 | 2.177 | 4.411 | −0.058 |

| Sold tangible fixed assets | 2.026 | 1.943 | 3.969 | −0.082 |

| Sales revenue | 1.322 | 1.048 | 2.37 | −0.274 |

| Cost of sales | 2.221 | 2.193 | 4.415 | −0.028 |

| Operating costs | 2.003 | 2.079 | 4.082 | 0.076 |

| Liabilities of companies | 1.691 | 1.421 | 3.112 | −0.27 |

| Equity of companies | 1.687 | 1.292 | 2.979 | −0.395 |

| Corporate assets | 2.139 | 1.951 | 4.09 | −0.187 |

| Debt ratio | 1.989 | 1.665 | 3.654 | −0.324 |

| Businesses entities and markets the HHI index ratio | 0.856 | 2.798 | 3.655 | 1.942 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peleckis, K. Determining the Level of Market Concentration in the Construction Sector—Case of Application of the HHI Index. Sustainability 2022, 14, 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020779

Peleckis K. Determining the Level of Market Concentration in the Construction Sector—Case of Application of the HHI Index. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020779

Chicago/Turabian StylePeleckis, Kęstutis. 2022. "Determining the Level of Market Concentration in the Construction Sector—Case of Application of the HHI Index" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020779

APA StylePeleckis, K. (2022). Determining the Level of Market Concentration in the Construction Sector—Case of Application of the HHI Index. Sustainability, 14(2), 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020779