1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered our lives in many different ways. On 17 December 2019, unknown pneumonia cases were reported in Wuhan, China, which resulted in a coronavirus disease outbreak [

1]. The virus is still prevalent, and new variants are frequently being detected, such as Delta and Omicron. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), more than 259 million people had contracted coronavirus as of 24 November 2021, and the disease has taken the lives of more than 5 million individuals. Numerous countries adopted a severe and strict quarantine, with 24 h or partial curfews affecting everyday life.

Several disease outbreaks have spread globally, such as SARS, Ebola, and H1N1. However, none of them had the massive impact seen with coronavirus. The COVID-19 pandemic caused enormous disruption to the global economy [

2], and exacerbated challenges faced by many countries, such as a lack of a sustainable economic and financial system. According to the OECD, foreign direct investment flows decreased by USD 846 billion in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic-driven economic contraction, which is a 38% decrease compared to 2019 [

3]. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported in April 2020 that the pandemic was unique and different from the worldwide crisis back in 2008, creating additional challenges affecting health and the economy and causing uncertainty [

4]. Furthermore, the global economy has decreased by more than 3% and seen a gradual loss of more than USD 9 trillion. The equity market has been severely affected by liquidity problems in financial institutions all over the world [

5]. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a massive shutdown in many countries, which troubled the supply chain and trading resources. Many governments worldwide imposed serious restrictions in order to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, which had a direct influence on most sectors, including education, health, and economics. A great deal of people lost their jobs, and many businesses were forced to close due to months of non-operation. COVID-19 put many people in near-isolation with strict social distancing measures and curfews. In fact, the real cost of the pandemic will still be measured in the years to come, affecting the triple bottom line: people, planet, and profit [

6].

As for Kuwait, COVID-19 had already impacted its economy tremendously. Although Kuwait is a small country, it is considered one of the wealthiest countries in the world. It has one of the highest incomes per capita, and its economy is primarily oil dependent. In 2016, Kuwait had the sixth highest GDP per capita globally [

7]. According to World Bank data in 2019, Kuwait’s GDP per capita was more than USD 32,000. The population is around 4 million. Two-thirds of the labour force works for the government sector, where the state funds employees’ salaries. In addition, Kuwait has different fund accounts. For example, Kuwait’s sovereign fund is valued at around USD 700 billion in assets [

8]. Furthermore, Kuwait has a public reserve fund and a future generation fund.

When COVID-19 hit Kuwait, the government depleted the public reserve fund of KD 18 billion (USD 65 billion) in 2020 and thought of borrowing money to prepare for fighting the spread of COVID-19. According to the Ministry of Finance, Kuwait’s budget deficit exceeded USD 36 billion in 2020, which is 175% more than the previous year [

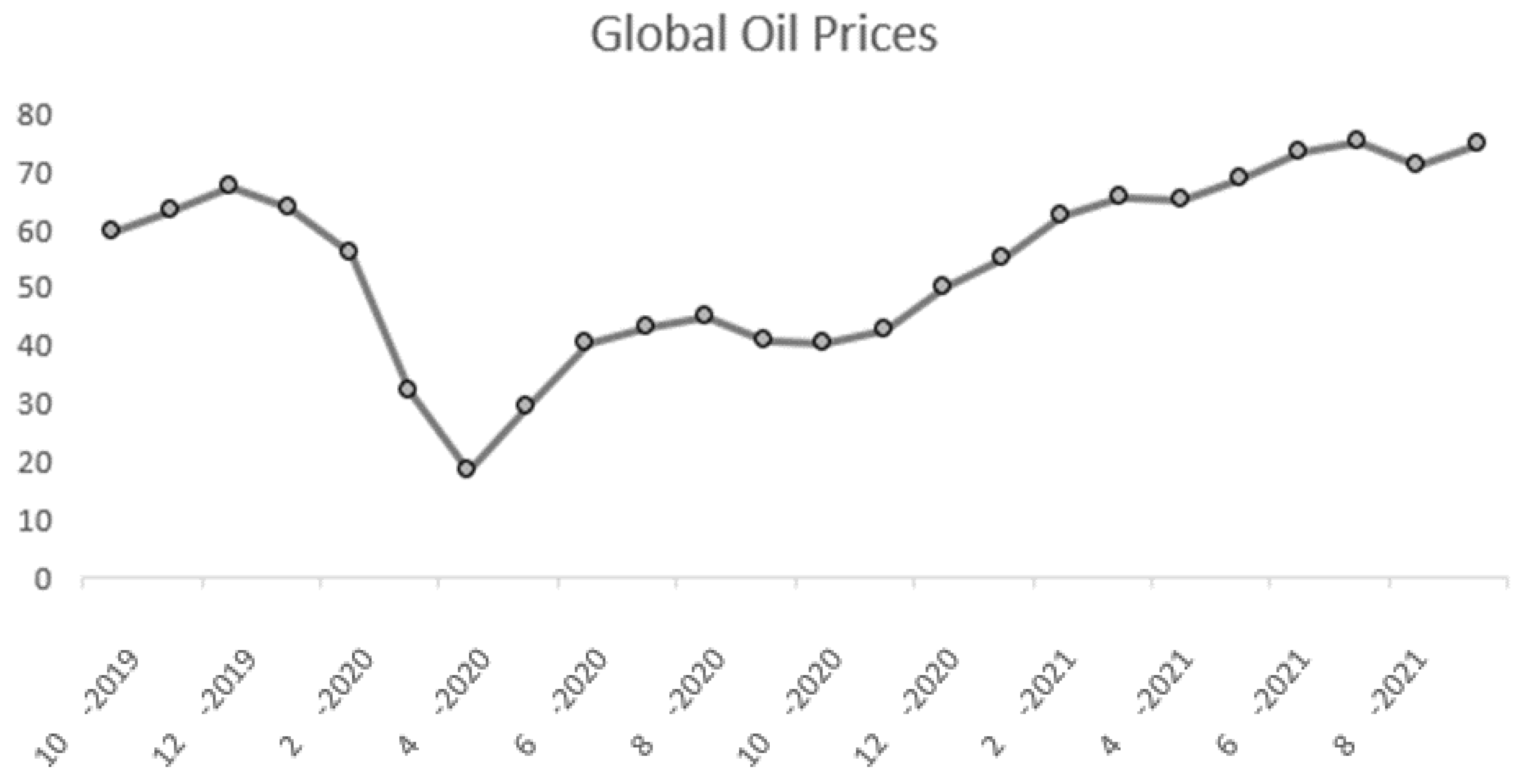

9]. The primary effect has come from a combination of forces, including shutdowns, travel restrictions, business closures, and supply chain disruptions that have hit the retail, hospitality, travel, and transportation sectors. Moreover, the collapse in the global oil prices was triggered by the coronavirus due to a shortage in demand and high supply, significantly affecting the government’s finances, as shown in

Figure 1. It is worth mentioning that most GCC countries depend heavily on oil as income revenue, including Kuwait. Therefore, the decline in oil prices greatly influenced Kuwait’s public finances. The oil revenue declined to 42.8% in 2020, which reshaped how the government responded to the crisis. Of course, this can have long-term implications for government spending that will further negatively affect economic growth. For instance, the fiscal deficit reached more than KD 13 billion or around 40% of GDP in 2020 and 9% in 2019, the weakest since the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait [

9]. It is expected that the government will further cut spending to bring the deficit under control.

Kuwait’s first coronavirus case was announced in February 2020 by the Ministry of Health [

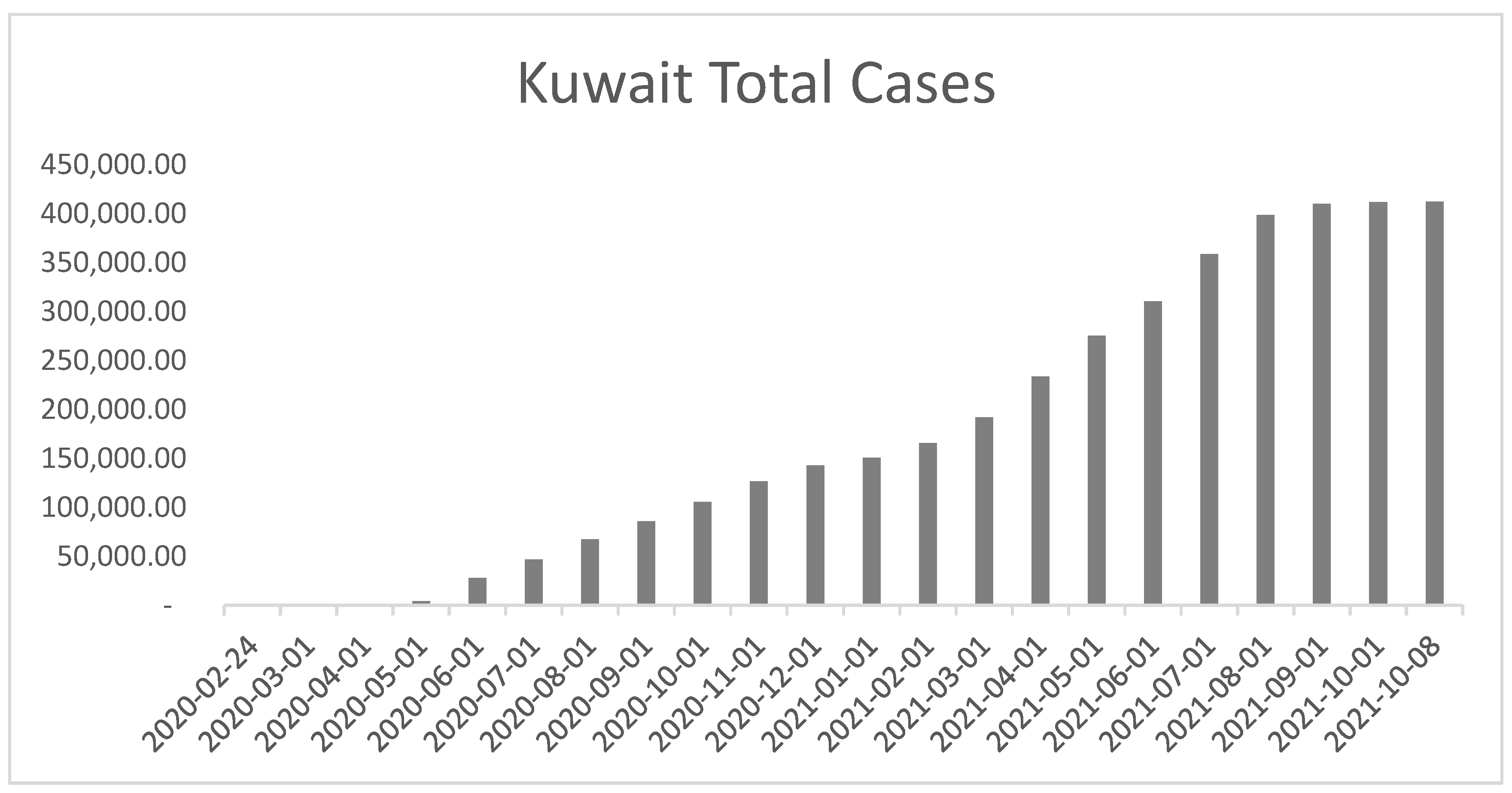

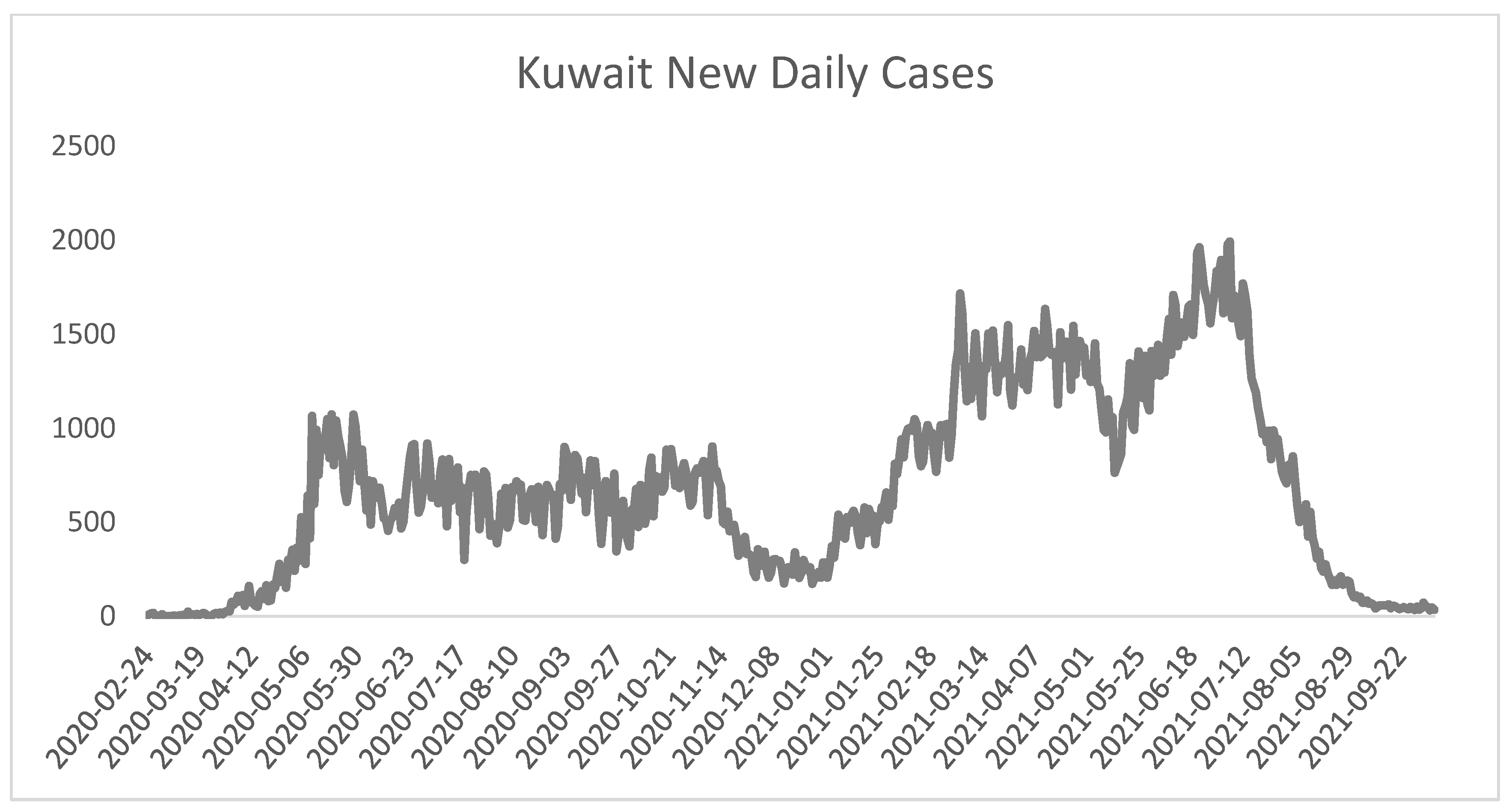

10]. COVID-19 infected more than 413 thousand people in Kuwait as of 25 November 2021, and caused more than 2400 deaths (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) [

11]. The government of Kuwait announced a public holiday starting 12 March 2020 and imposed a partial curfew (see

Table 1). Due to an increase in positive COVID-19 cases, the government set a full curfew on the 10th of May [

12]. Educational institutions were also suspended, and classes were later given online [

1]. Due to the lockdown, there was a substantial negative impact on Kuwait’s economy. For instance, many businesses closed down, with severe restrictions on industries and the service sector, which has suffered greatly as a result of limited cash flow. All flights were also suspended, except some cargo flights.

Kuwait needs a more sustainable financial system to cope with the detrimental effects that COVID-19 has initiated and move the economy towards more sustainable development. The new era of economic disaster needs an alternative financial system. Although Islamic finance is not isolated from the pandemic, it can be one of the alternative systems used to mitigate and recover from the impacts of COVID-19. Islamic banking and finance can have a genuine role in reaching the goals of sustainable development strategies. Islamic banking and finance assets have incurred an annual growth rate of 7.2% between 2013 and 2018, even climbing to the double digits in the years before 2013 since 1975 [

14].

Islamic banking and finance are essential in Kuwait’s development strategy based on higher ethical objectives, namely

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, which is a set of ethical principles and moral values covering all aspects of human life, bringing benefits and reducing harm to all humankind [

15]. Imam Al-Ghazali described

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah as the preservation of religion, human life, the mind, offspring, and wealth. Hence, Islamic finance is presumed to perform a significant task in the economic recovery plan under

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, particularly in the COVID-19 period. Therefore, it is important to include the role of Islamic banking and finance in the circulation, development, and preservation of wealth to attain social justice. For example, there are several fundamental functions of Islamic finance in recognising

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, such as the fact that Islamic finance provides commercial opportunities to enterprises, which could generate employment opportunities. Islamic finance under

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah preserves wealth, which could help to reconstruct the economy during COVID-19. This should occur in the context of economic well-being, justice, and the equitable distribution of wealth to achieve

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah. It is important to mention that

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah is not restricted to Muslim communities, but extends to all of humankind [

16].

The research examines the role of Islamic banking and finance based on Maqasid Al-Shari’ah to answer the main research question: How can Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, namely the preservation of wealth (hifth al mal) help Kuwait’s economy in the COVID-19 era?

This research is focused on how Islamic banking and finance can contribute to sustainable development in order to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19.

2. Literature Review

Unlike the conventional banking system, the business model of the Islamic finance system is based on Islamic law or (

Shari’ah). Islamic finance is prohibited from using

Riba (usury or interest) to generate money and uses an alternative method to accumulate funds. Consequently, Islamic banks face different challenges due to the additional risk contained in comparison with the conventional banking system, that is,

Shari’ah non-compliance risk and liquidity risk, where Islamic banks cannot borrow money when needed [

17]. Furthermore, regulations of central banks concerning Islamic banks were created through the use of the conventional bank model, making it even more challenging to compare conventional and Islamic business models and their structures [

18].

Significant differences appear between conventional and Islamic banking systems, including their business models, structure, products, and different associated risks. The authors of [

19] argued that the moral economy nature of Islamic finance distinguishes it from conventional finance and banking, and the direct reference to the moral economy brings social justice, growth, allocation of resources, and so on. Islamic banking faces unique challenges concerning risk and is different from conventional banking; this is natural because more significant difficulties arise from the nature of the specific risks and profit/loss sharing concepts that Islamic banks must manage [

20]. The main argument about the differences in practice between conventional and Islamic banks focuses on the business structure of their models. Islamic banks were constructed using

Shari’ah compliance (conformity to Islamic law). Their banking products are derived from

Shari’ah, which prohibits them from charging interest on their business transactions, creating a significant difference in operating conditions in comparison with conventional banks. For example, [

21] examined the financial performance of interest-free Islamic banking against interest-based conventional banking in Bahrain concerning profitability, liquidity risk, and credit risk during 1992–2001 (the post-Gulf War period). Nine financial ratios were utilised for making this comparison. The results showed no significant difference between Islamic and conventional banks in terms of profitability and liquidity, with some degrees of difference in credit performance.

On the other hand, Islamic finance can enrich the sustainable development goals (SDGs) through the use of several tools involving financial stability, allocating financial resources, social inclusiveness, and environmental protection [

22]. However, other studies include evidence that Islamic finance lacks the compliance to adopt the SDGs in regard to sustainable development, which may increase the pressure from stakeholders and regulatory challenges [

6].

It is believed that the vast ethical values of Islamic finance can sustain social well-being [

23]. Some authors, including [

24,

25,

26], revealed that Islamic banks failed to address the social objectives, which created a gap between aspirations and actual practice. However, many other authors, such as [

27,

28], have discussed some improvements in the exercise of Islamic banks concerning social objectives. Moreover, several authors, such as [

29,

30], indicated that Islamic finance has the potential to emerge as an alternative to the conventional financial system, which could be used to tackle the economic crisis caused by COVID-19.

The formation of the Islamic banking system was an effort to develop a sustainable and comprehensive socioeconomic structure representative of the true identity of Islamic values. For instance, Maqasid Al-Shari’ah has five main objectives: to protect life, property, health, religion, and dignity. Maqasid Al-Shari’ah implies the preservation of order, achievement of benefit, and prevention of harm or corruption; creating equality among people and causing the law to be revered, obeyed, and effective; and enabling society to become influential, respected, and confident (Vejzagic and Smolo, 2011).

There are two main models for transactions in Islamic banking and finance [

31,

32], which are closely related to welfarist and institutional sustainability. The welfarist model represents

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, realising enhanced social well-being, for example, by providing financing to productive entrepreneurs. In comparison, the institutional sustainability model extends the shareholders’ value maximisation [

33]. In fact, most Islamic banking and finance researchers do not agree on convening the balance between the welfarist and institutional sustainability view regarding

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah measurements.

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah and Finance

Several authors [

34,

35,

36,

37] have mentioned that Imam Al-Ghazali indicated that

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah can be achieved by preserving religion, human life, mind, offspring, and wealth. Hence, the primary objectives of

Shari’ah are to establish justice, eliminate prejudice, and alleviate hardship. Additionally, [

38] stated that

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah constitutes the spirit of all Islamic finance transactions. Alternatively, the authors of [

39] believe that

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah is a more comprehensive notion that goes beyond the transactional relationships of Islamic banking and its products. Therefore, to achieve social well-being, social justice, wealth circulation, equal distribution, the education of individuals, and sustainability,

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah needs to be fulfilled and prioritised over profit maximisation motives [

37,

40].

In terms of financial transactions, the core objectives of Maqasid Al-Shari’ah are the circulation, preservation, protection and transparency of wealth, as well as wealth development. Maqasid Al-Shari’ah ensures justice in wealth circulation, preventing harm and hardship in wealth.

Therefore, the wealth preservation concept not only suggests safeguarding wealth or protection from harm. Here, preservation is more associated with wealth development and expansion, fair distribution, and allocation [

41].

Consequently, wealth preservation indicates an important role of

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah—to achieve human well-being. For example, the author of [

16,

42] states that wealth is a trust from God that requires adequate use according to the foundation of rules and ethics. Therefore, Islamic banking and finance can play an important role in achieving well-being and the sustainable development goals through

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah to promote wealth circulation, which can assist with human development and realise

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah in terms of

hifth al-mal (safeguarding wealth).

This research aims to concentrate on the role of Islamic banking and finance with regard to human well-being and sustainable development via the Maqasid Al-Shari’ah framework. Hence, the study looks at how Islamic banking and finance tools can help to rebuild the economy based on Maqasid Al-Shari’ah to revitalise social, economic, and environmental welfare, especially in the COVID-19 era.

3. Methodology

Coronavirus caused uncertainty in our daily lives, requiring us to look at the multi-level impacts of COVID-19. The research approach utilises a theoretical concept in order to address the outcomes of COVID-19 and explore recovery options in the post-COVID-19 era. Hence, this study is based on the grounded theory method (GTM) [

43,

44]. The GTM was used to design a rigorous basis for qualitative research [

45]. The authors of [

44,

46] define the GTM as qualitative research strategies that offer a particular combination of implantation, conceptualising, abstracting, and theorising. It not unnecessary to specify any specific research strategy, data, or foundation using the GTM to develop a concept [

47]. However, the GTM is a systematic methodology that involves constructing a new theory in the social sciences by methodical gathering and analysis of the data available. The present study discusses the measures that can address the consequences and plan a potential economic recovery plan from coronavirus through the advantages of Islamic financial tools. The research examines the role of Islamic banking and finance based on the

Shari’ah principle (

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah), which deals with different economic, social, and environmental perspectives to answer the main research question:

How can Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, namely, the preservation of wealth, through the practice of Islamic finance, help Kuwait’s economy in the COVID-19 era?

Therefore, focusing on Kuwait, the main objective of the current study is to assess the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on Kuwait’s economy and develop policy guidelines on the mechanisms and approaches for sustainable development. The proposed model was adopted from other studies, drawing inspiration from authors such as [

48,

49] to achieve the following:

- -

To evaluate the role of Islamic finance in developing the mechanisms and supporting approaches related to improving the economy.

- -

To provide policy recommendations to stimulate the market and overall Kuwaiti economy.

4. Results and Discussion

Muslim economists agree that the primary objective of the Islamic moral economy is to form social justice, remove corruption in society, eliminate poverty, and reduce economic disparities [

50]. The Islamic economic system does not provide debt-based finance, which is considered an exploitative, unjust, and inequitable economy, but rather, e.g., through the institution of

Zakat (obligatory charity or Islamic tax). This interest-free system is a moral and ethical instrument of Islamic teachings, where the ultimate goal is to seek the pleasure of God [

51]. Interest elimination and

Zakat implementation are only considered as a single aspect of the Islamic economy. Islam aims to establish a fair and just economic order based on

Shari’ah principles. At the same time, Islamic economic system develops risk-sharing to increase stake-holding to create a sharing economy that is community-oriented and people-friendly (i.e.,

Mudharabah or profit-sharing financing, and

Musharakah or joint partnership) [

52]. For instance, Islamic banks are operating on Islamic standards, which will ensure growth with financial stability, equity, and distributive justice. Furthermore, the financier should become a fundamental investor in the profit-sharing economy, prepared to participate as an investor and an entrepreneur [

53].

Islamic banks in Kuwait play a significant role in the economy since there are five Islamic banks and five conventional banks. Kuwait’s economy mainly depends on oil for financing its budget. For example, the economy of Kuwait was seriously affected when the oil prices reached USD 20 per barrel due to low demand caused by COVID-19.

Not just oil prices were affected, but COVID-19 has changed our world in every aspect, including economic, social, and environmental sectors, creating a recession due to panic, supply and demand imbalances, shutdown strategies, and social distancing. Coronavirus developed an extreme atmosphere that negatively affected governments, businesses, and individuals, a situation that requires sustainable economic development to recover.

Islamic banking and finance can be used to aid recovery, particularly in the post-COVID-19 era. Islamic banks grow towards profitability and pooling funds, which lies at the front of the economy’s growth. For example,

Zakat payment of a nominal 2.5% of their net profit as one of the main pillars of Islam shows the significant role of Islamic banks in mitigating inequality between people and reducing poverty. As an Islamic model of taxation,

Zakat would balance the economy by distributing wealth to the community [

54]. Moreover,

Zakat would strengthen Islamic practices and help the needy due.

The role of Islamic finance is important in Kuwait’s development plan. It can play a significant role in economic recovery, particularly in the post-COVID-19 era. Islamic finance is accepted as ethical finance under the guidance of Maqasid Al-Shari’ah. For example, Islamic banks are allowed to charge administrative fees; however, they are not permitted to charge interest or shift the risk to customers. Islamic banks’ fair treatment through entrepreneurship is expected to pardon people suffering from poverty.

COVID-19 poses a challenge to Islamic banks in Kuwait. For instance, Islamic banks have a significant market share in small and medium enterprise sectors, as well as in retail lending, which suffered severe impacts during the pandemic. The lockdown that was imposed on the country affected all businesses, including Islamic banks. The government of Kuwait implemented a quantitative easing (QE) program, which deferred all conventional and Islamic finances, leaving banks with liquidity problems. Therefore, Islamic banks have no alternative but to support the government initiative to ease the burden of the majority of the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, all Islamic banks offered deferment of instalments to all customers regardless of their financial circumstances. In addition, Islamic banks played an essential role in supporting philanthropic societies in order to help people with curfew and deliver food, products, and services to prevent theft, violence, and crime.

Role of Islamic Banking and Finance

Islamic banks have a number of financial facilities, including

Sukuk (Islamic bond),

Zakat (mandatory donation),

Qardh-Al-Hassan (benevolent loan), and

Waqf (philanthropic deed or endowment) that can be utilised for mitigating the impact of coronavirus. In fact, Islamic banking and finance are believed to be secure financing, providing steady growth, stimulating financial stability, and reducing unemployment [

49]. Islamic finance prohibits

Riba,

Gharar, and excessive speculation, which lead to unfairness and unethical practice. Unethical practices may result in economic challenges, including income inequality and financial exclusion. Therefore, the role of Islamic finance is vital to reduce the issues of income inequality, financial exclusion, and unemployment.

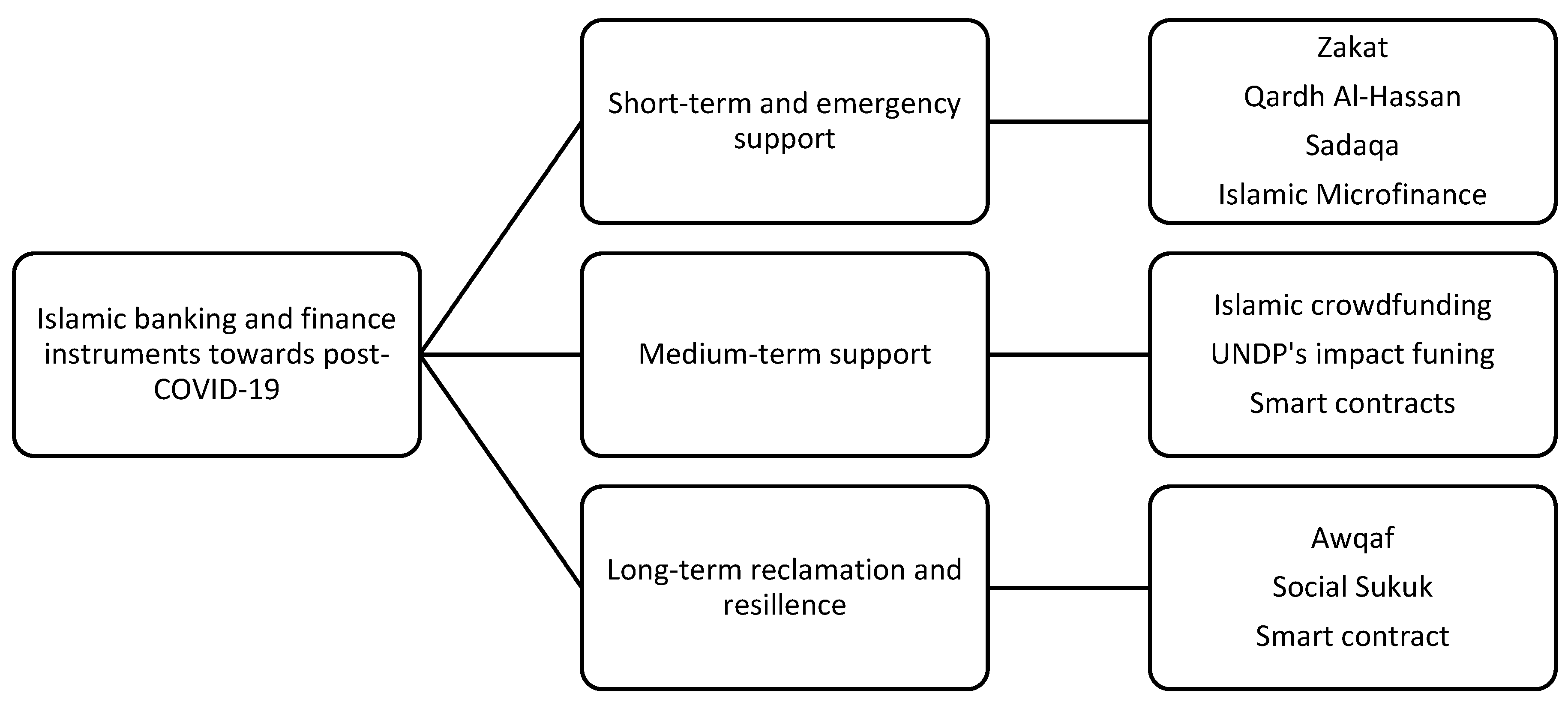

Islamic banking and finance concentrate on wealth distribution, not wealth accumulation; hence, they offer different tools to help society recover from COVID-19. For example, as seen in

Figure 4, in the short term, Islamic finance can provide the necessary funds to counter poverty and help with employment generation. Hence,

Zakat can play a vital role in providing urgent financial support to the needy.

Zakat has been shown to be a primary driving force in the economic system. In history,

Zakat was used as a primary source of state income, which plays an important part in

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah. As one of the central pillars of Islam,

Zakat can build social relations between the rich and the poor. More importantly, as a socio-economic mission,

Zakat is used as a mechanism that reduces the limits of inequality [

55]. For example, [

50] shows that the use of a high ratio of

Zakat by Islamic banks in the real investment sector indicates a high level of well-being in the community. Hence,

Zakat payment illustrates the significant role of Islamic banks and is an act of worship to mitigate the gap between the wealthy and the needy to overcome poverty.

Qardh Al-Hassan is considered one of the powerful instruments in Islamic banking and finance. It could be used as a potential means to aid recovery from COVID-19, especially for SMEs and individuals [

56].

Sadaqa (voluntary donation) can be used to support the individuals stuck in the lockdown and who lost their jobs due to COVID-19. Islamic financial institutions and banks would be the best option for

Sadaqa distribution in order to achieve efficiency in this process [

5]. In addition, Islamic microfinance stimulates entrepreneurs and can diminish unemployment and reduce poverty. At the same time, Islamic microfinance is considered to be one of the branches of Islamic banking tools, which can be used to provide financial assistance primarily to those who do not have access to the banking system. For instance, small-scale financial services can be used for people below the poverty line to generate income by engaging them with a self-employment project [

57].

Islamic finance focuses on the equity mode of financing instead of debt mode. For example, in the medium-term support stage, Islamic finance can help the changes and needs of financing sources for machine equipment. Islamic financial instruments including

Mudharabah (profit sharing financing),

Musharakah (joint partnership), and

Murabaha (cost-plus financing) can be utilised to enhance the economy and align financing activities with the SDGs. For example, AlBaraka Bank in 2018 introduced a USD 600 million initiative in collaboration with UNDP, which covers different regions such as the Middle East and North Africa, Asia, and Europe [

49].

Salam (sale of a deferred commodity for a current price) and

Istisna (build or manufacture an asset) sales contracts could be used by Islamic banks and governments to enhance the liquidity of the private sector and contribute to their survival. Finally, the

Ijarah (renting or leasing) contracts could help the individuals and SMEs affected by COVID-19 [

5].

In long-term reclamation and resilience, Islamic banking and finance tools such as Sukuk, Awqaf, and intelligent contracts can be utilised for fighting the economic impact of COVID-19 and facilitate economic, social, and environmental recovery towards sustainable development. The Islamic Development Bank (IDB) issued in June 2020 the first Sukuk in the world in order to mitigate the health and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in its member countries, totalling USD 1.5 billion with a five-year tenure.

5. Conclusions

Due to the effect of COVID-19 on the economy, it is obvious that there is a need to pursue long-term sustainability, including economic, social, and environmental sectors. This issue cannot be compromised or have temporary solutions. The research posits the role of Islamic finance as an alternative type of finance, offering guidelines to reduce the diverse impact of coronavirus and to improve and ascertain some possible solutions through which recovery from the COVID-19 disaster can be achieved.

The results should provide direction for policymakers in Kuwait regarding how Islamic banking and finance should be utilised to stimulate the economy. Islamic banking and finance can offer human well-being and sustainable development via achieving Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, thereby playing an important role in wealth distribution among wider society by avoiding the concentration of wealth among the wealthy and providing fair employment opportunities. This includes wealth expansion and growth, protection from harm, and adequate circulation. Islamic banking and finance offer proper tools through which to preserve wealth in the economy.

Some argue that Islamic banking and finance, with their current structure, cannot significantly influence the development of the societies in which they operate. However, this does not mean that the Islamic banking sector cannot impact economic growth. Islamic banks and financial institutions should adapt their financing tools to elevate the harm affecting society due to the COVID-19 pandemic and contribute to the achievement of human well-being. In addition, to achieve Maqasid Al-Shari’ah, Islamic banking and finance should reach a balance in economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

Even though there is no single policy or country to be taken as a great example in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis, this research, using Kuwait as a case study, can help facilitate potential solutions utilising Islamic finance tools in other countries.