Improving Education for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Chinese Technical Universities: A Quest for Building a Sustainable Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How to achieve a mutually beneficial relationship and build a community of interests, development, and destiny; how to use the specific features of technical universities to connect with industrial partners while focusing on applications in higher education, and to seize the opportunity of the transformation and development of technical universities.

- How to combine the particularities of the regional environment, the regional integrated development strategy and the national innovation-driven development strategy, and precisely address the necessities of the provincial and municipal industries in terms of talent training.

2. Status of Education for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Chinese Technical Universities

2.1. The Educational Concepts and Goals Are Relatively Lagging, Which Causes a Split in the Logical Relationship among Innovation, Entrepreneurship, University Major and Industry

2.2. The Educational Organization System Lacks Coherence, Which Weakens the Mechanisms Put in Place for Collaborative Education

2.3. The Curriculum Is Dull and Does Not Involve Practical or Personalized Guidance

2.4. The Incubation Platforms Are Relatively Lacking, Restricting Project Cultivation and Docking Resources

- The Ministry of Education’s entrepreneurial talent training innovation pilot zone, innovation and entrepreneurship education reform demonstration school, and innovation and entrepreneurship practice education center.

- The entrepreneurship platform and entrepreneurship demonstration base of the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

- The makerspace and university science park of the Ministry of Science and Technology.

- The demonstration base of mass innovation and entrepreneurship of the National Development and Reform Commission.

- The modern industry college of the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

2.5. The Cooperation between Professional Teachers and Entrepreneurial Mentors Is Often Not Substantive

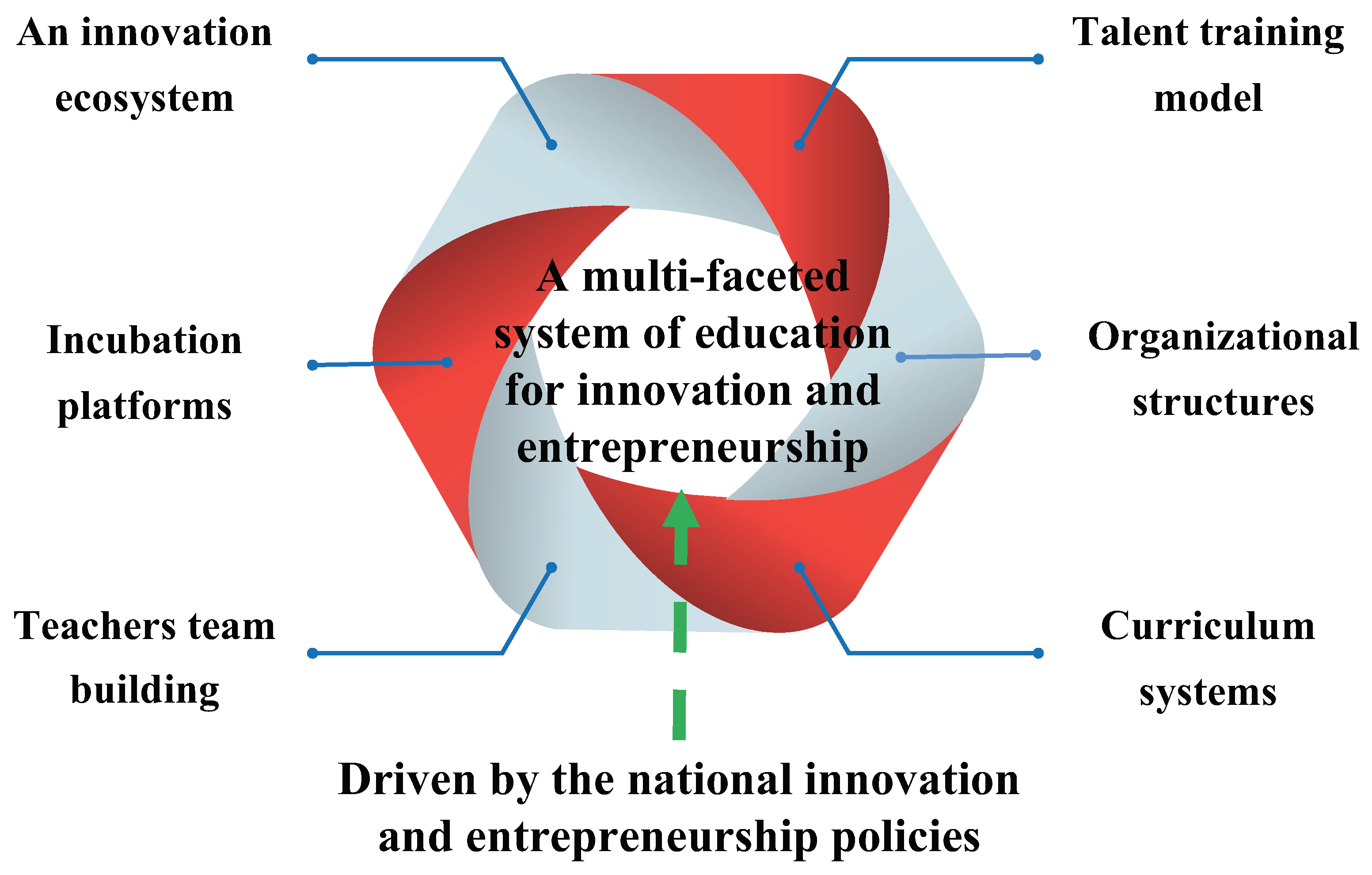

3. Necessary Measures for Improving Education for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Systemically and Conceptually

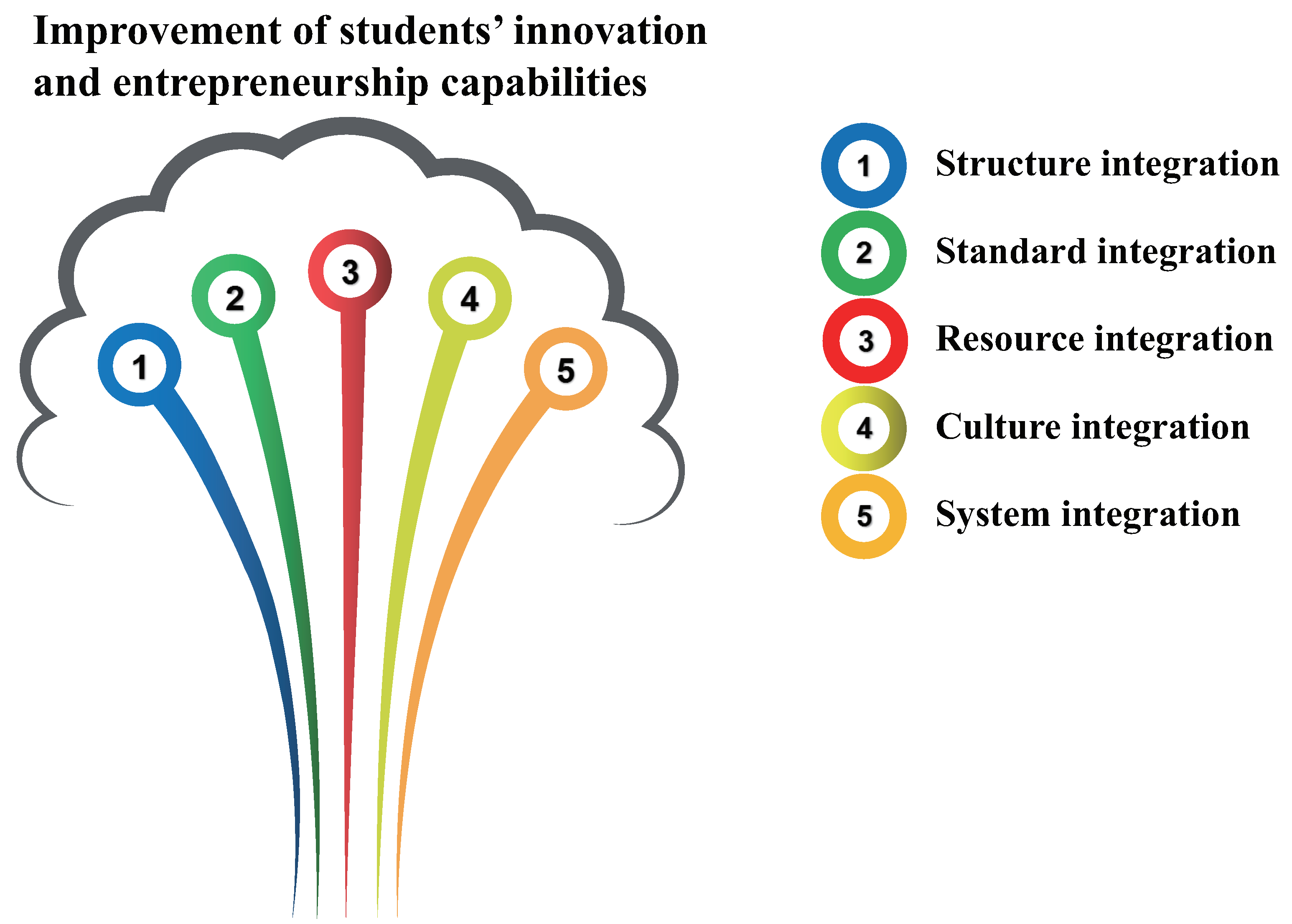

3.1. “5+1” Talent Training Model

- Integration between industrial structures and the catalogue of university specialisationsThe catalogue of specialisations in technical universities should be highly consistent and highly coupled with the orientation of regional industrial development, ideally in such a way that they would cross-promote each other. In agreement with their development goals and talent training specifications and also with the needs of the local and regional industries with regard to applications-oriented talents, technical universities need to improve the dynamic adjustment mechanism of their catalogue of specialisations in such a way as to promote the connection between enrollment, training and employment and to account for the emergence of new technological trends around the world. Finally, study plans oriented towards precise specializations and close connection with the industrial and innovation chains must be established in technical universities.

- Integration between specialisation standards and professional requirementsTechnical universities must follow future directions of industrial development, corresponding to different specialisations and subdivisions of industries. During the period of reconstruction and reestablishment of majors and specialisations, referring to the Ministry of Education’s first-class undergraduate specialisation construction standards and engineering education professional certifications, technical universities should identify the characteristics of specialisations and then form a pattern of professional standardization and specialisation, which takes root in local industries and deepens the integration between industry and education.

- Integration between educational resources and industrial resourcesIt is necessary to establish a steering committee consisting of senior enterprise managers, industry experts and university teachers in order to formulate the blueprints of a talent training program with a multi-level curricular system and teaching materials that integrate production and education. By making use of all pooled resources, experience and know-how, technical universities can then explore the establishment of industrial colleges or research institutes that can integrate talent training, innovation and entrepreneurship, high-tech research and development, and social services.

- Integration between educational culture and enterprise cultureTechnical universities should organize lectures and various social activities to strengthen the promotion of the best practices in enterprise culture, so that the enterprise culture could find its way into the daily lives of college students. At the same time, through internship training programs, college students could adapt to the corporate culture, in order to develop professional habits and professional ethics in advance of the actual employment.

- Integration between the educational system and industrial research and development mechanismsEnterprises should formulate actual problems encountered in production and R&D as study cases for students to discuss and/or solve. As a result, on the one hand, students can learn by doing and can refine their critical thinking and problem-solving capabilities in a realistic environment, on actual real-world problems. On the other hand, this may lead to specific problems in enterprises, such as technical bottlenecks, usability issues, technological upgrades, being solved or mitigated.

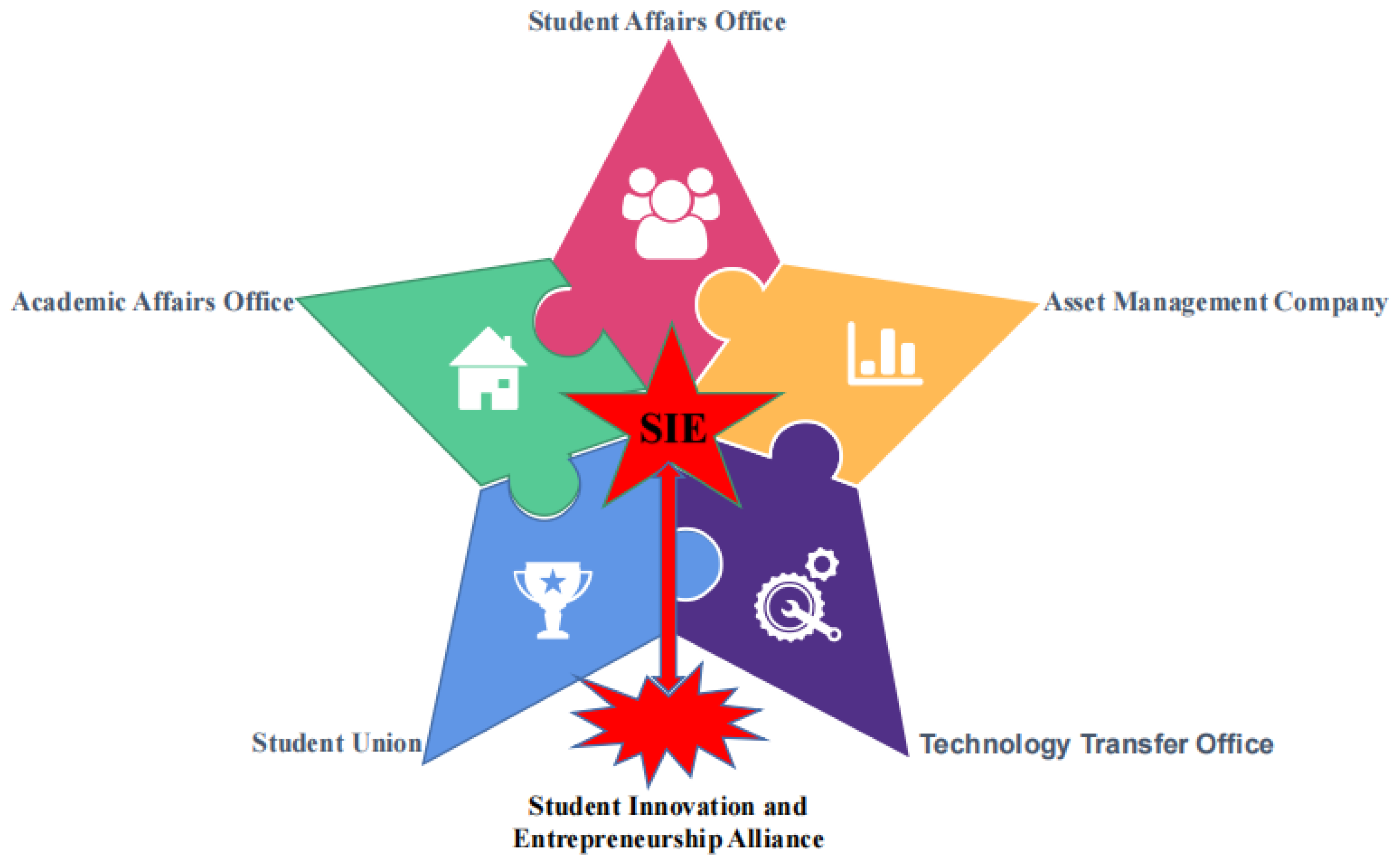

3.2. Organizational Structures for Talent Training

3.3. Curriculum Systems for Talent Training

3.4. Teacher Team Building for Talent Training

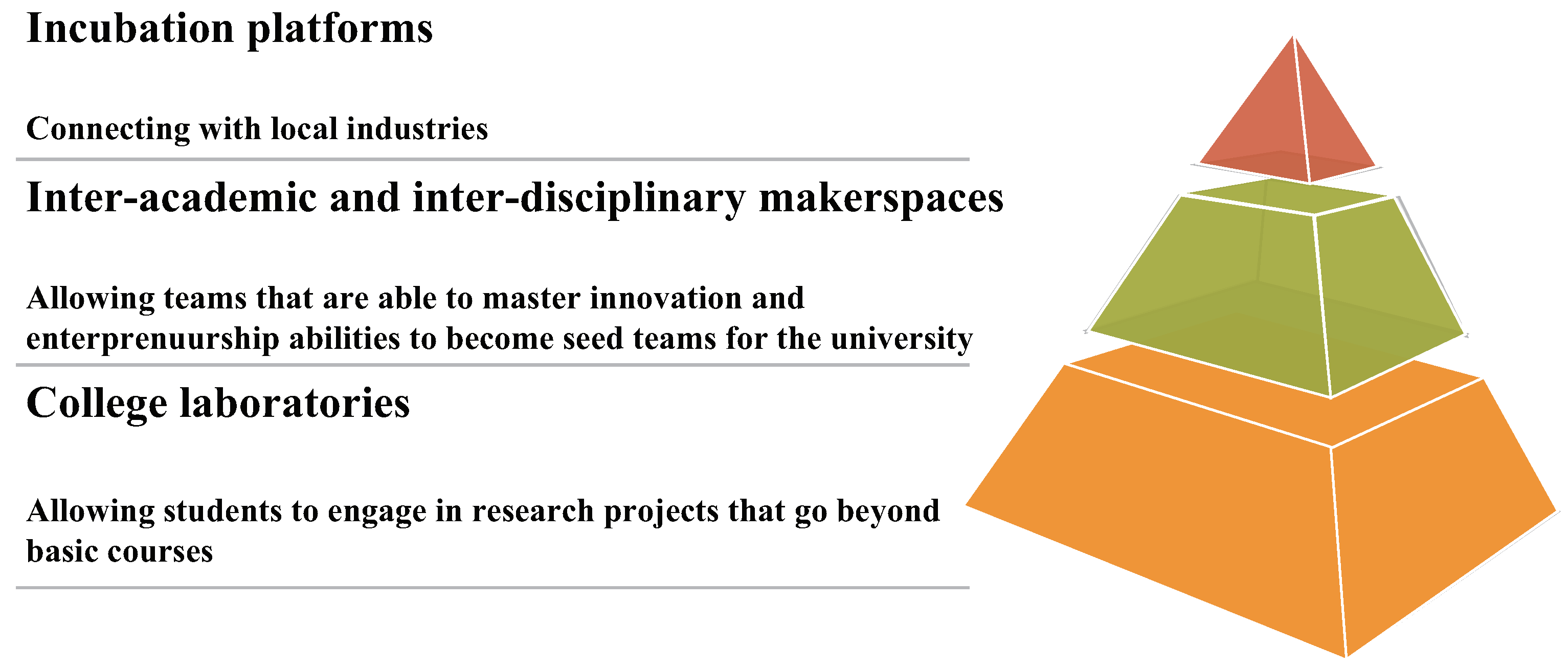

3.5. Creating Incubation Platforms for Talent Training

- Pyramid baseDepartment and schools in the university are the main units of talent training, relying on college laboratories to complete the experimental projects assigned in the curriculum of the training program in order to meet the needs of all students. The colleges should also open up a certain area of dedicated space to establish a makerspace with a distinct environment that allows students to engage in research projects that go beyond basic courses.

- Pyramid bodyThe universities rely on the establishment of entrepreneurship parks or science parks open to college students and on well-funded industrial colleges to form inter-academic and inter-disciplinary makerspaces and then dynamically select distinguishing teams and projects from different schools to enter this makerspace. In the context of the integration between industry and education, the university provides venues, facilities and supporting policies, through the collaborative assistance of professional teachers on campus and entrepreneurship mentors off-campus, for resident teams and projects that accept re-cultivation, re-polishing and re-incubation. The teams that are able to master innovation and entrepreneurship abilities become seed teams for the university and are intended to be active on the stage of various innovation and entrepreneurship university activities.

- Pyramid topThe successful teams trained on campus are recommended to enter the off-campus incubation platform, connect with local industries, and continue to acquire experience and grow in the market environment. These successful teams will not, hopefully, break up when they graduate, getting rid of the greenhouse effect in the post-campus era, and continue to have strong vitality. A few years later, their growth and achievements will have a demonstrative, positive impact on the student teams on campus. A similar phenomenon occurred for Stanford University, known as the “Heart of Silicon Valley”, since nearly 80% of well-known companies in Silicon Valley such as Apple, Google, Hewlett-Packard, Yahoo, Cisco, and so forth are the results of collaborative entrepreneurship between Stanford University’s teachers and students.

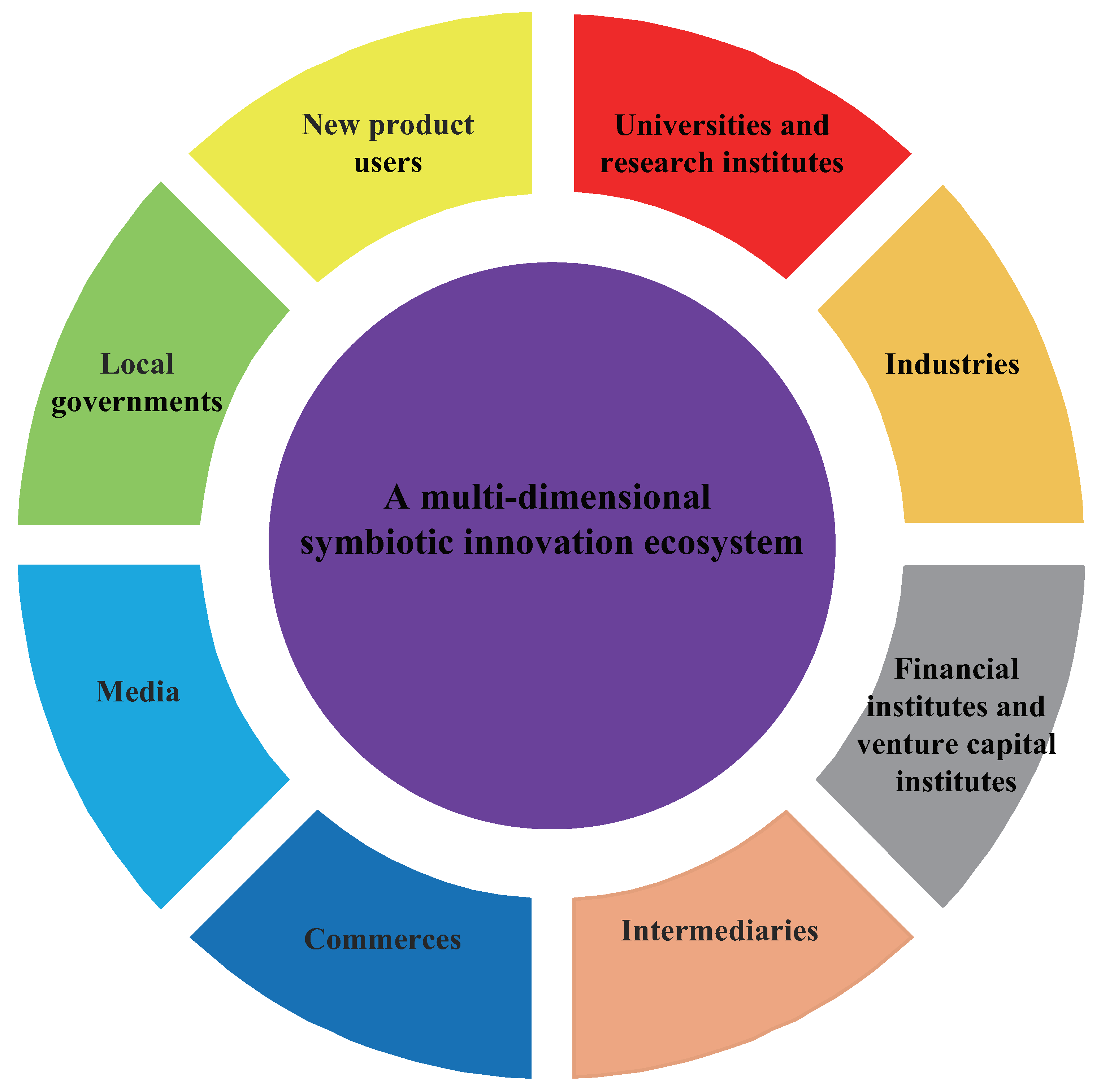

3.6. Building an Innovation Ecosystem for Talent Training

- Local governments: Adopt subsidy strategies to promote innovation and ensure the participation of interested parties by providing incentives to cooperate [29].

- New product users: Discovering and then meeting the needs of new product users promotes scientific and technological innovation, keeping the product up with the times.

- Universities and research institutes: Cultivate talents with innovative ability and pioneering spirit and ensure their cooperation with industrial partners to the best of their abilities by utilizing the support of off-campus organizations and trade associations.

- Industrial partners: One of the main parties in the collaboration, enjoying the support of the local government. Ensure the transfer of teachers’ and students’ knowledge and research to the assembly lines by preparing the basis for implementing the scientific knowledge gained in the academic stage.

- Financial institutions and venture capital institutions: As these institutions are well aware of the regional financial policies and economic development trends, they can play an effective role in selecting and financing the industrialization of worthy scientific and technological achievements.

- Intermediaries: Give full play to the role of bridges and ties, so that the elements of innovation can be effectively connected and gathered.

- Commerces: Build channels for the purchase of raw materials and for product sales.

- Media: The national and local innovation policies cannot be fully accepted by people without vigorous media propaganda. The promotion of new technologies and new products cannot be done without mediatic cooperation. The media is like a window that allows us to peek into the world of innovation.

4. The Design of the MPEIE Method and Its Usage

Data Sources and Motivations for the Choices of Performance Indicators

- Document review: All official documents related to the education for innovation and entrepreneurship in China have been reviewed.

- Interviews: It has been attempted to engage teachers, students and off-campus mentors in one-on-one conversations. A total of 115 teachers and mentors outside the university and 853 students from 13 schools accepted to be subjects of our interviews.

- Focus groups: Discussions has been started in a group of people involved in the symbiotic innovation ecosystems, questions relevant to the subject of our research being asked and answered.

- Surveys: A total of 2693 questionnaires with open-ended questions have been distributed on-line, of which 2586 were effectively recovered.

- Secondary research: Related books and scholarly articles have been surveyed, existing data being collected as text or images.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, New High-tech Strategy “Innovation for Germany”. 2014. Available online: https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/EN/Artikel/Technology/high-tech-strategy-for-germany.html (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Ministère de l’Économie des Finances et de la Relance, New Industrial France. 2015. Available online: https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/PDF/web-dp-indus-ang.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, FY2018 Measures to Promote Manufacturing Technology (White Paper on Monodzukuri 2019). 2019. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2019/06/20190611002/20190611002_02.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Gartner, W.; Vesper, K. Experiments in entrepreneurship education: Success and failures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 9, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewrick, M.; Omar, M.; Raeside, R.; Sailer, K. Education for entrepreneurship and innovation: “Management capabilities for sustainable growth and success”. World Journal of Enterprenuership. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ankrah, S.; Al-Tabbaa, O. Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Sahut, J.M.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Hikkerova, L. The effects of government subsidies on the sustainable innovation of university-industry collaboration. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121233. [Google Scholar]

- Hutschenreiter, G.; Zhang, G. China’s Quest for Innovation-Driven Growth—The Policy Dimension. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2007, 7, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, A.P. Systems engineering and information technology: Catalysts for total quality in industry and education. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1992, 22, 833–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P.F. Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Practice and Principles. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 1985, 4, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, C. A Research on the Mode of Cultivation of Innovative Talents in Engineering Undergraduate A Case Study of Rose-Hulman Technology Institute. Res. High. Educ. Eng. 2007, 3, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nataraajan, R.; Angur, M.G. Innovative ability and entrepreneurial activity: Two factors to enhance “quality of life”. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Build Innovation Chain of Yangtze River Economic Belt to Promote Transformation and Upgrading of Regional Economy. China Dev. 2015, 15, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, F.; Wei, K.; Chen, Y.; Ju, M. Construction of an index system for qualitative evaluation of undergraduate nursing students innovative ability: A Delphi study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4379–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainow, R. Training and education of entrepreneurs: The current state of the literature. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 1986, 3, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A.A. Enterprise Culture and Education: Understanding Enterprise Education and Its Links with Small Business, Entrepreneurship and Wider Educational Goals. Int. Small Bus. J. 1993, 11, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkema, S.; Schout, H. Incorporating student-centred learning in innovation and entrepreneurship education. Eur. J. Educ. 2010, 43, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, H.; Hong, W.C. Sustainable development evaluation of innovation and entrepreneurship education of clean energy major in colleges and universities based on SPA-VFS and GRNN optimized by chaos bat algorithm. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusikka, T.; Kinnunen, T.K.; Kostiainen, J. Public transport innovation platform boosting Intelligent Transport System value chains. Util. Policy 2020, 62, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.S.; Zheng, Z.X.; Chen, J. A multi-platform collaboration innovation ecosystem: The case of China. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeslag-Kreunen, M.G.M.; Van der Klink, M.R.; Van den Bossche, P.; Gijselaers, W.H. Leadership for team learning: The case of university teacher teams. High. Educ. 2017, 75, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bray, M.J.; Lee, J.N. University revenues from technology transfer: Licensing fees versus equity positions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, C.S.; Einar, R.; Rooksby, J.H. Beyond formal university technology transfer: Innovative pathways for knowledge exchange. J. Technol. Transf. 2020, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H. The Triple Helix: University-Industry-Government Innovation in Action; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The triple helix—University-industry-government relations: A laboratory for knowledge-based economic development. EASST Rev. 1995, 14, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The endless transition: A “triple helix” of university–industry–government relations. Minerva 1998, 36, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “Mode 2” to a triple helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, M.V.; Shaw, J.M. Teaching engineering innovation, design, and leadership through a community of practice. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 31, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Elsner, W.; Zhang, Z.; Berger, R. Collaborative innovation and policy support: The emergence of trilateral networks. Appl. Econ. 2019, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A.; Chatterjee, S. A design science research methodology for information systems research. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Pinto, E.B.; Machado, R.J.; Araújo, M.; Pontes, A. A program and project management approach for collaborative university-industry R&D funded contracts. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 64, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar]

- D’Este, P.; Patel, P. University–industry linkages in the UK: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Res. Policy 2007, 36, 1295–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Neely, A.; Walsh, K. How should firms evaluate success in university–industry alliances? A performance measurement system. R&D Manag. 2011, 41, 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Seppo, M.; Lilles, A. Indicators measuring university-industry cooperation. Discuss. Est. Econ. Policy 2012, 20, 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Tijssen, R.J.; Van Leeuwen, T.N.; Van Wijk, E. Benchmarking university-industry research cooperation worldwide: Performance measurements and indicators based on co-authorship data for the world’s largest universities. Res. Eval. 2009, 18, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Pinto, E.B.; Araújo, M.; Magalhães, P.; Machado, R.J. A method for measuring the success of collaborative university-industry R&D funded contracts. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 121, 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.; Barbosa, J.; Pinto, E.B.; Araújo, M.; Machado, R.J. Applying a method for measuring the performance of university-industry R&D collaborations: Case study analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 164, 424–432. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Phase Weight | Process Component | Component Weight | Performace Indicator | PI Weight | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation phase | 30% | Organizational structure | 20% | 1. Percentage of administrative offices guaranteeing education for innovation and entrepreneurship | 30% | |

| 2. Percentage of student organizations involved in education for innovation and entrepreneurship | 30% | |||||

| 3. Rate of off-campus collaborators with their participation in education for innovation and entrepreneurship (performed/planned) | 40% | |||||

| Curriculum | 30% | 4. Rate of elementary courses (performed/planned) | 25% | |||

| system | 5. Rate of intermediate courses (performed/planned) | 25% | ||||

| 6. Rate of advanced courses (performed/planned) | 25% | |||||

| 7. Rate of elite courses (performed/planned) | 25% | |||||

| Teacher team | 20% | 8. Average h-index of the academic staff | 25% | [34] | ||

| 9. Percentage of off-campus mentors with a higher education qualification | 25% | [34] | ||||

| 10. Percentage of school teachers with past experience | 10% | |||||

| 11. Percentage of school teachers satisfied with the contribution of their participation | 20% | |||||

| 12. Percentage of off-campus mentors satisfied with the contribution of their participation | 20% | |||||

| Incubation platform | 30% | 13. Average number of laboratories provided by each college | 50% | |||

| 14. Number of makerspaces provided by the university | 50% |

| Phase | Phase Weight | Process Component | Component Weight | Performace Indicator | PI Weight | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits | 70% | Collaboration | 10% | 15. Rate of steering committee meetings (performed/planned) | 25% | [32] |

| delivery | intensity | 16. Rate of workplace meetings (performed/planned) | 25% | [32] | ||

| phase | 17. Rate of progress meetings (performed/planned) | 25% | [32] | |||

| 18. Rate of result-sharing events (performed/planned) | 25% | [32] | ||||

| Human capital | 15% | 19. Rate of students win awards in subject competitions | 30% | |||

| 20. Rate of students win awards in top innovation and entrepreneurship competitions | 30% | |||||

| 21. Rate of university graduates serving local industries | 40% | [34] | ||||

| New knowledge | 10% | 22. Rate of publications (performed/planned) | 50% | [33] | ||

| 23. Rate of joint publications (performed/planned) | 50% | [35] | ||||

| Technology | 10% | 24. Rate of patent application (performed/planned) | 100% | [33] | ||

| achievements | ||||||

| Education | 20% | 25. Rate of teaching achievement award (performed/planned) | 20% | |||

| achievements | 26. Rate of publishing innovation and entrepreneurship textbooks (performed/planned) | 20% | ||||

| 27. Rate of innovation and entrepreneurship research project application (performed/planned) | 20% | |||||

| 28. Rate of innovation and entrepreneurship lectures (performed/planned) | 20% | |||||

| 29. Rate of innovation and entrepreneurship social activities (performed/planned) | 20% | |||||

| Incubation achievements | 20% | 30. Rate of projects incubated by the industry collaborators (performed/planned) | 30% | |||

| 31. Rate of university graduates starting their own businesses | 30% | |||||

| 32. Rate of provincial and national incubation platforms (performed/planned) | 40% | |||||

| Financing | 15% | 33. Rate of government funding (performed/planned) | 20% | |||

| achievements | 34. Rate of university funding (performed/planned) | 20% | ||||

| 35. Rate of enterprise funding (performed/planned) | 20% | |||||

| 36. Rate of bank and other financial institution funding (performed/planned) | 20% | |||||

| 37. Rate of Angel investor funding (performed/planned) | 20% |

| PI | Result | Score | Weighted Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 83% | 5 | 0.09 |

| 2 | 75% | 4 | 0.072 |

| 3 | 5/7 = 71% | 4 | 0.096 |

| 4 | 1/1 = 100% | 5 | 0.1123 |

| 5 | 7/13 = 54% | 3 | 0.0675 |

| 6 | 5/13 = 39% | 2 | 0.045 |

| 7 | 4/2 = 200% | 5 | 0.1125 |

| 8 | 82% | 5 | 0.075 |

| 9 | 73% | 4 | 0.06 |

| 10 | 76% | 4 | 0.024 |

| 11 | 65.8% | 4 | 0.048 |

| 12 | 68% | 4 | 0.048 |

| 13 | 100% | 5 | 0.225 |

| 14 | 69% | 4 | 0.18 |

| 15 | 7/10 = 70% | 4 | 0.07 |

| 16 | 7/10 = 70% | 4 | 0.07 |

| 17 | 6/8 = 75% | 4 | 0.07 |

| 18 | 6/10 = 60% | 4 | 0.07 |

| 19 | 110% | 5 | 0.1575 |

| 20 | 50% | 3 | 0.0945 |

| 21 | 85% | 5 | 0.21 |

| 22 | 35/50 = 70% | 4 | 0.14 |

| 23 | 8/15 = 54% | 3 | 0.105 |

| 24 | 16/20 = 80% | 5 | 0.35 |

| 25 | 1/2 = 50% | 3 | 0.084 |

| 26 | 2/1 = 200% | 5 | 0.14 |

| 27 | 345/200 = 173% | 5 | 0.14 |

| 28 | 15/20 = 75% | 4 | 0.112 |

| 29 | 10/12 = 83% | 5 | 0.14 |

| 30 | 15/13 = 115% | 5 | 0.21 |

| 31 | 56% | 3 | 0.126 |

| 32 | 2/3 = 67% | 4 | 0.224 |

| 33 | 35/50 = 70% | 4 | 0.084 |

| 34 | 50/200 = 25% | 2 | 0.042 |

| 35 | 20/30 = 67% | 3 | 0.063 |

| 36 | 5/20 = 25% | 2 | 0.042 |

| 37 | 5/20 = 25% | 2 | 0.042 |

| Overall score | 4.0415 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, M.; Zhang, H.; Georgescu, P.; Li, T.; Zhang, B. Improving Education for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Chinese Technical Universities: A Quest for Building a Sustainable Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020595

Lv M, Zhang H, Georgescu P, Li T, Zhang B. Improving Education for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Chinese Technical Universities: A Quest for Building a Sustainable Framework. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020595

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Min, Hong Zhang, Paul Georgescu, Tan Li, and Bing Zhang. 2022. "Improving Education for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Chinese Technical Universities: A Quest for Building a Sustainable Framework" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020595

APA StyleLv, M., Zhang, H., Georgescu, P., Li, T., & Zhang, B. (2022). Improving Education for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Chinese Technical Universities: A Quest for Building a Sustainable Framework. Sustainability, 14(2), 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020595