Linking Digital HRM Practices with HRM Effectiveness: The Moderate Role of HRM Capability Maturity from the Adaptive Structuration Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

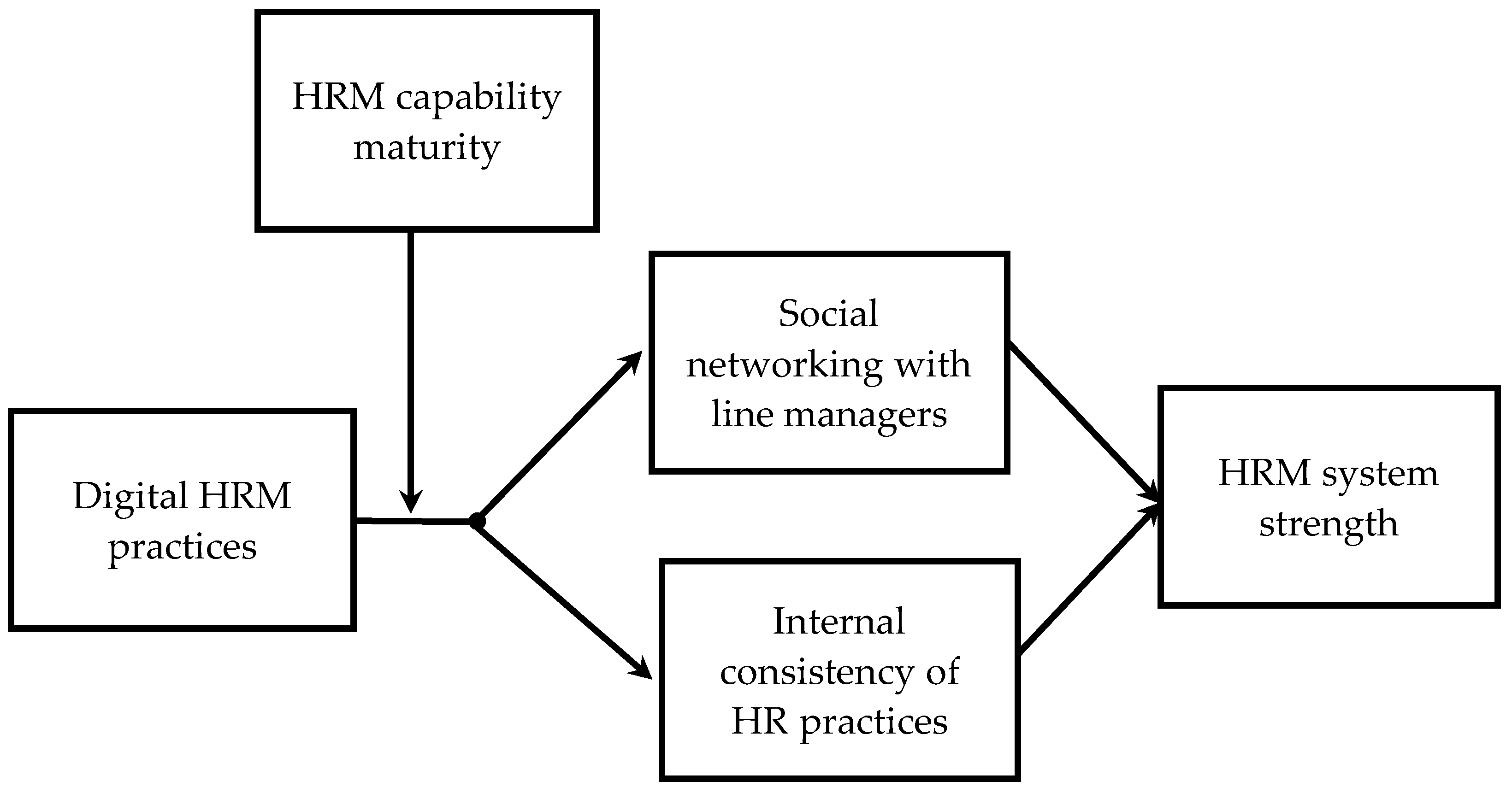

2. Theoretical Grounding and Hypothesis Development

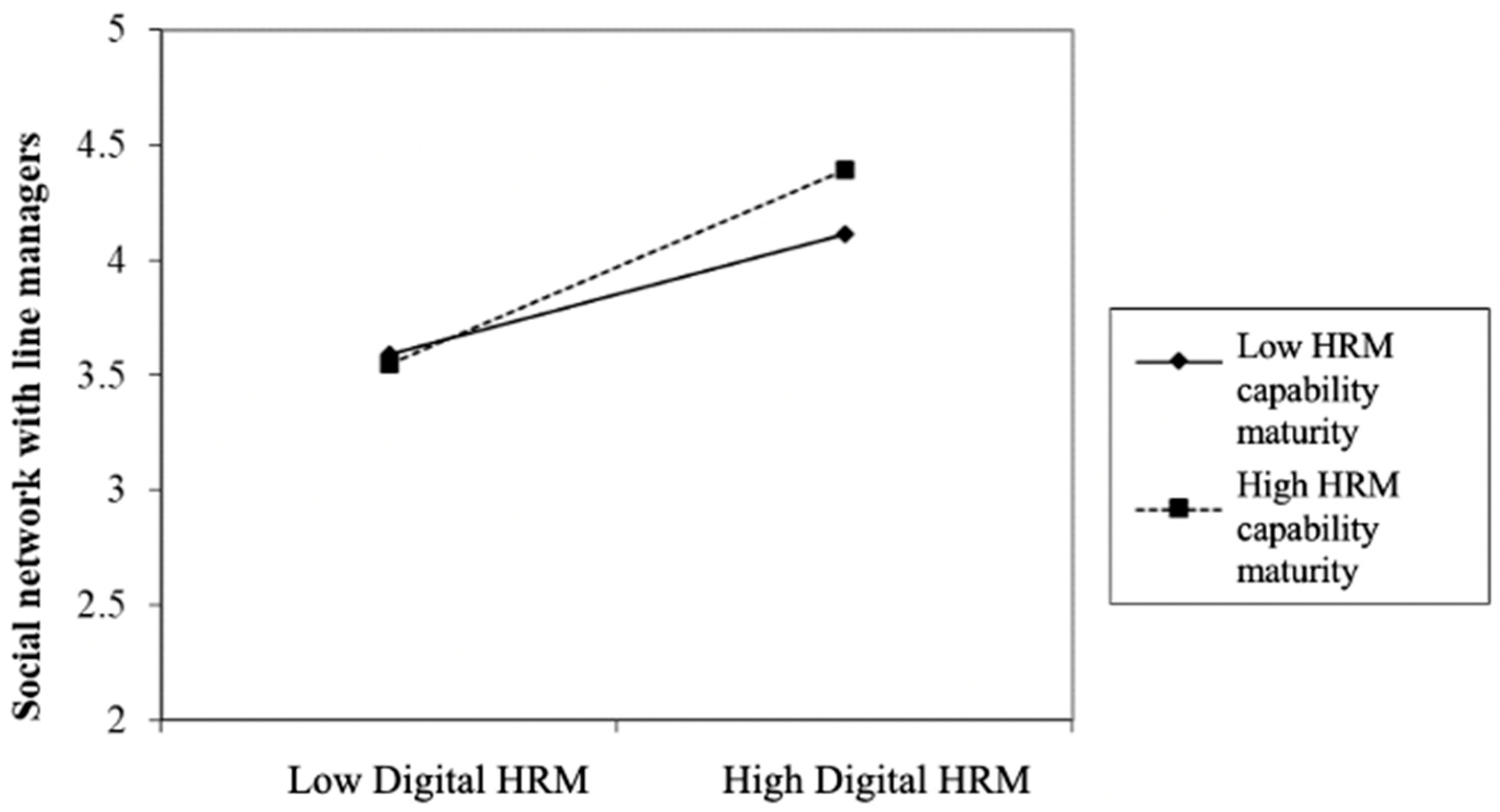

2.1. The Interactive Effect of Digital HRM Practices and HRM Capability Maturity on HR Managers’ Social Networking with Line Managers

2.2. HR Managers’ Social Networking with Line Managers and HRM System Strength

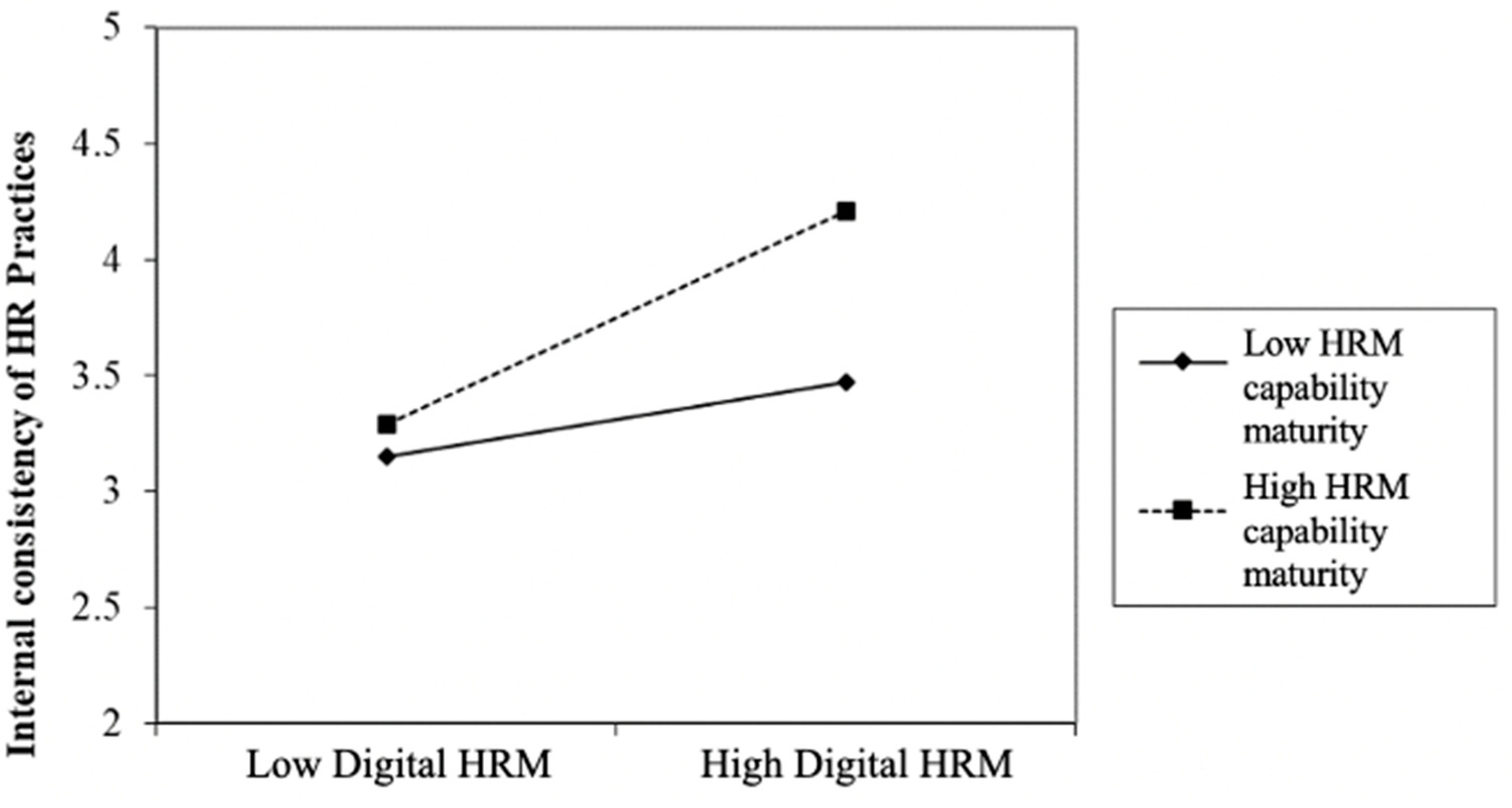

2.3. The Interactive Effect of Digital HRM Practices and HRM Capability Maturity on the Internal Consistency of HR Practices

2.4. Internal Consistency of HR Practices and HRM System Strength

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Digital HRM Practices

3.2.2. HRM Capability Maturity

3.2.3. HR Managers’ Social Networking with Line Managers

3.2.4. Internal Consistency of HR Practices

3.2.5. HRM System Strength

3.2.6. Control Variables

4. Results

Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practice Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, G.; Chang, X.; Wang, L. The impact of HRM digitalization on firm performance: Investigating three-way interactions. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisen. Available online: https://news.alphalio.cn/PDF/2021%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E4%BA%BA%E5%8A%9B%E8%B5%84%E6%BA%90%E7%AE%A1%E7%90%86%E5%B9%B4%E5%BA%A6%E8%A7%82%E5%AF%9F-%E5%8C%97%E6%A3%AE-2021.1-49%E9%A1%B5.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Accenture. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-120/Accenture-TechVision-2020-Exec-Summary-Report-2.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Minbaeva, D.B. Building credible human capital analytics for organizational competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, U.; Jensen, T.B.; Stein, M.-K. Breaking the vicious cycle of algorithmic management: A virtue ethics approach to people analytics. Inf. Organ. 2020, 30, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Esch, P.; Black, J.S.; Ferolie, J. Marketing AI recruitment: The next phase in job application and selection. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, D. Commentary on Radical HRM innovation and competitive advantage: The Moneyball story—Moneyball lessons: The transition from HR intuition to HR analytics. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 45, 140–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler, E.E., III; Levenson, A.; Boudreau, J.W. HR metrics and analytics: Use and impact. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 27, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, A. Using workforce analytics to improve strategy execution. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiemann, W.A.; Seibert, J.H.; Blankenship, M.H. Putting human capital analytics to work: Predicting and driving business success. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, S.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Wu, L. Three-Way Complementarities: Performance Pay, Human Resource Analytics, and Information Technology. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Budhwar, P.; Patel, C.; Srikanth, N.R. May the bots be with you! Delivering HR cost-effectiveness and individualized employee experiences in an MNE. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Hitt, L. Paradox lost? Firm-level evidence on the returns to information systems spending. Manag. Sci. 1996, 42, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrave, D.; Charlwood, A.; Kirkpatrick, I.; Lawrence, M.; Stuart, M. HR and analytics: Why HR is set to fail the big data challenge. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minbaeva, D. Human capital analytics: Why aren’t we there? Introduction to the special issue. J. Organ. Eff. 2017, 4, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.S.; Webster, J. The use of technologies in the recruiting, screening, and selection processes for job candidates. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2003, 11, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddick, C.G. Human resources information systems in Texas city governments: Scope and perception of its effectiveness. Public Pers. Manag. 2009, 38, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trullen, J.; Bos-Nehles, A.; Valverde, M. From intended to actual and beyond: A cross-disciplinary view of (human resource management) implementation. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 150–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.; Konrad, A.M. Causality between high-performance work systems and organizational performance. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 973–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanctis, G.; Poole, M.S. Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarouk, T.; Harms, R.; Lepak, D. Does e-HRM lead to better HRM service? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 1332–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Han, J.H. An expanded conceptualization of line managers’ involvement in human resource management. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, J.; Kim, S. Team manager’s implementation, high performance work systems intensity, and performance: A multilevel investigation. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2690–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panos, S.; Bellou, V. Maximizing e-HRM outcomes: A moderated mediation path. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 1088–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryscynski, D.; Reeves, C.; Stice-Lusvardi, R.; Ulrich, M.; Russell, G. Analytical abilities and the performance of HR professionals. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, J.H.; Boudreau, J.W. An evidence-based review of HR Analytics. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.H.; Sodeman, W.A. The questions we ask: Opportunities and challenges for using big data analytics to strategically manage human capital resources. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, B.; Hefley, B.; Miller, S. People Capability Maturity Model (P-CMM), version 2.0; Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie-Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2009.

- Hannon, J.; Jelf, G.; Brandes, D. Human resource information systems: Operational issues and strategic considerations in a global environment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1996, 7, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarouk, T.; Parry, E.; Furtmueller, E. Electronic HRM: Four decades of research on adoption and consequences. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 2, 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Zapata-Phelan, C.P. Trends in theory building and theory testing: A five-decade study of the Academy of Management Journal. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1281–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaosar, G.A.A.; Hoque, M.R.; Bao, Y. Investigation on the precursors to and effects of human resource information system use: The case of a developing country. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1485131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Kurnia, S. Antecedents and outcomes of human resource information system (HRIS) use. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2012, 6, 603–623. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, S.D.; Lepak, D.P.; Bartol, K.M. Virtual HR: The impact of information technology on the human resource professional. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudi, E.; Park, S.M. Unveiling the value creation process of electronic human resource management: An Indonesian case. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 83–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaszewski, K.M.; Stone, D.L.; Stone-Romero, E.F. The effects of the ability to choose the type of human resources system on perceptions of invasion of privacy and system satisfaction. J. Bus. Psychol. 2008, 23, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, B.; Morath, R.; Curtin, P.; Heil, M. Public sector use of technology in managing human resources. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2006, 16, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.; Björkman, I. In the eyes of the beholder: The HRM capabilities of the HR function as perceived by managers and professionals. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2015, 25, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, E. An examination of e-HRM as a means to increase the value of the HR function. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1146–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voermans, M.; van Veldhoven, M. Attitude towards E-HRM: An empirical study at Philips. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, V.Y.; Lafleur, G. Information technology usage and human resource roles and effectiveness. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 47, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruël, H.; Van der Kaap, H. E-HRM usage and value creation. Does a facilitating context matter? Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 26, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.G.R.; Masum, A.K.M.; Beh, L.-S.; Hong, C.S. Critical factors influencing decision to adopt human resource information system (HRIS) in hospitals. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustad, E.; Munkvold, B.E. IT-supported competence management: A case study at Ericsson. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2005, 22, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masum, A.K.M.; Alam, M.G.R.; Alam, M.S.; Azad, M.A.K. Adopting factors of electronic human resource management: Evidence from Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovations in Science, Engineering and Technology (ICISET), International Islamic University Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh, 28–29 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Qi, X.; Jinnah, M.S. Factors affecting the adoption of HRIS by the Bangladeshi banking and financial sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3, 1262107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaosar, G.M.A.A. Determinants of the Adoption of Human Resources Information Systems in a Developing Country: An Empirical Study. Int. Technol. Manag. Rev. 2017, 6, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cascio, W.; Boudreau, J. Investing in People: Financial Impact of Human Resource Initiatives; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, K.C.; Valentine, M.A.; Christin, A. Algorithms at work: The new contested terrain of control. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 366–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, F.L. Modeling an HR shared services center: Experience of an MNC in the United Kingdom. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 45, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Guo, Y.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. A conceptual artificial intelligence application framework in human resource management. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Electronic Business, Guilin, China, 2–6 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier, S.; Piazza, F. Artificial intelligence techniques in human resource management—A conceptual exploration. In Intelligent Techniques in Engineering Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G.; Reddington, M. Theorizing the links between e-HR and strategic HRM: A model, case illustration and reflections. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1553–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, S. Research in e-HRM: Review and implications. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; McMahan, G.C. Theoretical perspectives for strategic human resource management. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Collins, C.J. Human resource management and unit performance in knowledge-intensive work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambe, P.; Cappelli, P.; Yakubovich, V. Artificial intelligence in human resources management: Challenges and a path forward. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, V.Y.; Petit, A. Conditions for successful human resource information systems. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 36, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruël, H.; Bondarouk, T.; Looise, J.K. E-HRM: Innovation or irritation. An explorative empirical study in five large companies on web-based HRM. Manag. Rev. 2004, 15, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D.P.; Liao, H.; Chung, Y.; Harden, E.E. A conceptual review of human resource management systems in strategic human resource management research. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 25, 217–271. [Google Scholar]

- Minbaeva, D.; Pedersen, T.; Björkman, I.; Fey, C.F.; Park, H.J. MNC knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity, and HRM. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 34, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.; Gupta, N. Human resource management practices and organizational effectiveness: Internal fit matters. J. Organ. Eff. 2016, 3, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Messersmith, J.G.; Lepak, D.P. Walking the tightrope: An assessment of the relationship between high-performance work systems and organizational ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1420–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Su, Z.X.; Wright, P.M. The “HR-line-connecting HRM system” and its effects on employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauff, S.; Alewell, D.; Katrin Hansen, N. HRM system strength and HRM target achievement—Toward a broader understanding of HRM processes. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall College Div.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, P.; Minette, K.; Joy, D.; Michaels, J. The use of an automated employment recruiting and screening system for temporary professional employees: A case study. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2004, 43, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oiry, E. Electronic Human Resource Management: Organizational Responses to Role Conflicts Created by E-Learning. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2010, 13, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beulen, E. The contribution of a global service provider’s Human Resources Information System (HRIS) to staff retention in emerging markets: Comparing issues and implications in six developing countries. Inf. Technol. People 2009, 22, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-H. Electronic human resource management and organizational innovation: The roles of information technology and virtual organizational structure. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.K. Human capital analytics: The winding road. J. Organ. Eff. 2017, 4, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.-J. Application and development of the people capability maturity model level of an organisation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.S.; Tahmasebi, R.; Yazdani, H. Maturity assessment of HRM processes based on HR process survey tool: A case study. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 610–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.; Younas, M.; Saeed, T. Impact of Moderating Role of e-Administration on Training, Perfromance Appraisal and Organizational Performance. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2017, 10, 3764–3770. [Google Scholar]

- Bissola, R.; Imperatori, B. The unexpected side of relational e-HRM: Developing trust in the HR department. Empl. Relat. 2014, 36, 376–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, S.M. The link between e-HRM use and HRM effectiveness: An empirical study. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 1281–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J.; Lin, P.-F.; Lu, C.-M.; Tsao, C.-W. The moderation effect of HR strength on the relationship between employee commitment and job performance. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2007, 35, 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S.J.; Li, M.; Restubog, S.L.D. Management, organizational justice and emotional exhaustion among Chinese migrant workers: Evidence from two manufacturing firms. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2012, 50, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sels, L.; De Winne, S.; Maes, J.; Delmotte, J.; Faems, D.; Forrier, A. Unravelling the HRM—Performance link: Value-creating and cost-increasing effects of small business HRM. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenole, N.; Ferrar, J.; Feinzig, S. The Power of People: Learn How Successful Organizations Use Workforce Analytics to Improve Business Performance; FT Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mondore, S.; Douthitt, S.; Carson, M. Maximizing the impact and effectiveness of HR analytics to drive business outcomes. People Strategy 2011, 34, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, J.; Cascio, W. Human capital analytics: Why are we not there? J. Organ. Eff. 2017, 4, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H.; Harris, J.; Shapiro, J. Competing on Talent Analytics. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, F. Impact of Human Resource Information System (HRIS): Substituting or Enhancing HR Function. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1425905 (accessed on 19 January 2011).

- Lego, J. Creating a business case for your organization’s web-based HR initiative. In Web-Based Human Resources; AJ Walker, R.M., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York City, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Organization Age | 15.64 | 17.35 | |||||||||||||||

| 2.Organization Dummy 1 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.15 ** | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Organization Dummy 2 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.10 ** | 0.34 ** | |||||||||||||

| 4. Organization Dummy 3 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.26 ** | 0.49 ** | ||||||||||||

| 5. Organization Dummy 4 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.17 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.25 ** | |||||||||||

| 6. Organization Dummy 5 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.15 ** | 0.06 * | 0.20 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.11 ** | ||||||||||

| 7. Organization Dummy 6 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.11 ** | 0.05 | 0.15 ** | 0.05 * | 0.09 ** | 0.25 ** | |||||||||

| 8. Organization Dummy 7 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.06 * | 0.25 ** | 0.44 ** | ||||||||

| 9. Organization Dummy 8 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.14 ** | 0.02 | 0.12 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.32 ** | |||||||

| 10. Digital HRM practices | 4.05 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.05 * | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 * | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 * | 0.04 | 0.93 | |||||

| 11. HR managers’ social networking with line managers | 3.66 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.11 ** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 * | 0.24 ** | |||||

| 12. Internal consistency of HR practices | 3.46 | 1.22 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.07 ** | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.17 ** | 0.21 ** | ||||

| 13. HRM capability maturity | 2.66 | 1.14 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.11 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.24 ** | |||

| 14. HRM system strength | 3.95 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.08 * | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 ** | 0.05 * | 0.04 | 0.06 * | 0.06 * | 0.71 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.91 | |

| Model | c2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Δc2 (Δdf) | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model | 2665.70 (929) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| Four-factor model | 2735.33 (932) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 69.63 (3) | 0.03 |

| Three-factor model | 3156.90 (935) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.04 | 491.20 (6) | 0.03 |

| Two-factor model | 3157.26 (936) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.04 | 491.56 (7) | 0.03 |

| Relationships | Social Networking with Line Managers | Internal Consistency of HR Practices | HRM System Strength | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95%CI | B | SE | 95%CI | B | SE | 95%CI | |

| Direct Effect | |||||||||

| Organization Age | 0.00 * | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 * | 0.00 | [0.01, 0.00] | 0.00 | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.00] |

| Organization Dummy 1 | 0.16 | 0.11 | [0.37, 0.05] | 0.30 | 0.17 | [0.02, 0.63] | 0.03 | 0.08 | [0.12, 0.20] |

| Organization Dummy 2 | 0.20 | 0.11 | [0.41, 0.00] | 0.29 | 0.15 | [0.01, 0.59] | 0.04 | 0.08 | [0.20, 0.12] |

| Organization Dummy 3 | 0.18 | 0.11 | [0.38, 0.04] | 0.23 | 0.16 | [0.07, 0.55] | 0.05 | 0.08 | [0.20, 0.12] |

| Organization Dummy 4 | 0.10 | 0.12 | [0.33, 0.13] | 0.12 | 0.17 | [0.21, 0.43] | 0.09 | 0.08 | [0.25, 0.06] |

| Organization Dummy 5 | 0.31 ** | 0.10 | [0.51, 0.11] | 0.50 *** | 0.14 | [0.80, 0.22] | 0.02 | 0.07 | [0.14, 0.12] |

| Organization Dummy 6 | 0.12 | 0.09 | [0.30, 0.05] | 0.23 | 0.13 | [0.47, 0.02] | 0.05 | 0.06 | [0.06, 0.17] |

| Organization Dummy 7 | 0.05 | 0.09 | [0.23, 0.12] | 0.28 * | 0.13 | [0.52, 0.03] | 0.03 | 0.05 | [0.07, 0.14] |

| Organization Dummy 8 | 0.01 | 0.09 | [0.19, 0.18] | 0.27 * | 0.13 | [0.52, 0.01] | 0.04 | 0.06 | [0.15, 0.08] |

| Digital HRM practices | 0.34 *** | 0.04 | [0.26, 0.40] | 0.31 *** | 0.05 | [0.22, 0.40] | 0.81 *** | 0.03 | [0.75, 0.86] |

| HR managers’ social net-working with line managers | 0.10 *** | 0.02 | [0.07, 0.14] | ||||||

| Internal consistency of HR practices | 0.03 ** | 0.01 | [0.01, 0.06] | ||||||

| Interactive effect | |||||||||

| HRM capability maturity | 0.06 *** | 0.02 | [0.03, 0.10] | 0.22 *** | 0.03 | [0.17, 0.27] | 0.02 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.04] |

| Digital HRM practices HRM capability maturity | 0.08 * | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.14] | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | [0.06, 0.23] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.05] |

| Relationships | (DHRM→Social Networking with Line Managers → HRM System Strength) | (DHRM→Internal Consistency of HR Practices → HRM System Strength) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95%CI | B | 95%CI | |

| Indirect relationship | 0.04 *** | [0.02, 0.05] | 0.01 * | [0.00, 0.02] |

| Conditional indirect relationships | ||||

| High HRM capability maturity (+1SD) | 0.05 *** | [0.03, 0.07] | 0.02 * | [0.01, 0.03] |

| Low HRM capability maturity (−1SD) | 0.02 ** | [0.01, 0.04] | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.01] |

| Difference between high and low | 0.02 * | [0.00, 0.04] | 0.01 * | [0.00, 0.03] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, G. Linking Digital HRM Practices with HRM Effectiveness: The Moderate Role of HRM Capability Maturity from the Adaptive Structuration Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14021003

Wang L, Zhou Y, Zheng G. Linking Digital HRM Practices with HRM Effectiveness: The Moderate Role of HRM Capability Maturity from the Adaptive Structuration Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14021003

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lijun, Yu Zhou, and Guoyang Zheng. 2022. "Linking Digital HRM Practices with HRM Effectiveness: The Moderate Role of HRM Capability Maturity from the Adaptive Structuration Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14021003

APA StyleWang, L., Zhou, Y., & Zheng, G. (2022). Linking Digital HRM Practices with HRM Effectiveness: The Moderate Role of HRM Capability Maturity from the Adaptive Structuration Perspective. Sustainability, 14(2), 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14021003