1. Introduction

As time goes on, there are more and more media that carry narrative stories, from the oral to the written word, then film, and now virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) [

1]. In recent years, there have been numerous studies on the application of AR, VR, and mixed reality in the physical spaces, such as museums, which consider how to unveil the multifaceted nature of objects by providing additional multimedia contents [

2,

3]. Based on smartphones and tablets as supporting hardware, some augmented skins and skeletons can be viewed by visitors at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington D. C. [

4]. Technology makes up for information that the exhibits themselves cannot directly show to the visitors. While museum exhibitions are designed to tell a story, the visitor’s journey through them is a metaphorical, a from start-to-finish way of reading the story. In museums, one can often see exhibits that bear the marks and signs of damage left by age. Although they have been skillfully restored and reinstated, or have computer-generated ‘original photographs’, the visitor may still not have a good idea of the historical or contextual information about these exhibits, and it is still up to the visitor’s imagination to expand upon them. As a result, the process of visiting an exhibition becomes a process in which the audience’s imagination is involved in the ‘conceptualization’ of the narrative story. AR technology can improve this conceptualization process by enhancing the users’ sense of presence [

5], narrative engagement and reflection. However, there is little research on AR-based narratives in other types of physical places, such as open urban spaces.

According to Diao and Lu’s view, a sustainable urban regeneration should take into account both the physical space and the inheritance of cultural resources [

6]. AR is defined as the synchronization of physical space with an overlay of dynamic digital data [

7]. This combination is usually site- or object-specific, which commonly occurs in real time through participants’ engagement with devices, and mediates the environment in a way that previous media can’t achieve [

8]. This characteristic of AR technology makes it easier to link narratives to physical places at the same time as creating a location-based experience [

9]. The application of AR in the context of urban space can physically integrate cultural resources into the physical facilities of the city and can reflect the uniqueness of the architecture in its spatial and temporal dimensions [

10]. This will help to express the diachronic factors of urban space in spatial places [

11].

AR technology allows people to see the world in a different way. From a tourism perspective, traditional tourism mainly follows a fixed itinerary, and although it is divided into individual and guided tours, tourists lack a multi-level interactive experience of the scenic spots and local culture. Further, some attractions are not open to the public in order to better preserve, for example, historical buildings. This not only affects the visitor’s overall understanding of the area, but also limits the promotion of the location. However, if AR technology is used, then it is possible to show those attractions that are not open to the public in a certain space. This would allow visitors to have a fuller picture of the information and backstory of the tourist attraction. Today, there are still old houses that have been restored and opened to the public, but for visitors, such attractions mostly mean some ruins or restorations or replicas that do not allow for a complete and deep, as well as objective, understanding of these monuments. With AR technology, however, it is possible to input real scenes from history, based on time and space into a computer and then restore them to the real scene through digital technology. In other words, the classic look of the historical sites at various points is brought to the visitor’s attention. In addition, AR technology is well placed to overcome the many limitations and allow visitors to experience the stunning beauty of the original architecture.

However, it is challenging to create an AR-based space corresponding to the features and layout of the urban physical places. Karapanos et al. found that viewers have better mental imagery when watching a video story in a physical place where the surroundings match the narrative atmosphere [

12]. Following this argument, this research introduces a non-fictional approach to create an open narrative in the physical space of the city, namely the Bund, in order to explore a new approach to sustainable urban regeneration, based on AR technology. In this approach, we want to use avatars to simulate the psychological journey of the protagonist from a first point of view, based on a real historical scene or setting, thus delivering a superior immersion.

3. Interpretation of the Cultural Information

The most important starting point for the application of augmented reality is to enhance the user’s perception of real-world space. The spatial element is therefore very important in the narrative of augmented reality. This study uses the Bund in Shanghai as an example to show how non-fiction can be used to construct space for narrative. The Bund, located on the banks of the Huangpu River in the Huangpu district of central Shanghai, is known as the Outer Huangpu Bund. This area, leased to the British from 1844, is considered to be the starting point of the old Shanghai lease and the modern history of Shanghai. Fifty-two classical and revival buildings of various styles stand in the Bund, known as the ‘World Architecture Expo’. They are significant cultural relics and typical buildings of modern China and one of the landmarks of Shanghai. In November 1996, it was listed by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China as part of the fourth batch of national key cultural relics protective units.

The Bund has a wide variety of multi-storey and high-rise buildings. For example, the Asia Building (formerly the Shanghai Institute of Design and Metallurgy), the Shanghai Club (now the East Wind Hotel), the Shanghai Pudong Development Bank (formerly the HSBC Building), and the Jardine Matheson Building (now the Foreign Trade Mansion) are of British Classical, Neoclassical and Renaissance styles, respectively. There are also many other styles, such as French classicism, French mansion, Gothic, Baroque, modern Western, Eastern Indian, Eclectic, Chinese-Western, etc., which co-exist with the architecture of the world. Therefore, the collection of buildings stretching from Jinling Road in the south to the Waibaidu Bridge on the Suzhou River in the north are hailed as the “World Architecture Expo”. These buildings, which blend classicism and modernism, have become the symbol of Shanghai. There are 33 buildings in the Bund, some of which are still in use by the authorities. For instance, the No. 13 Shanghai Customs House, was finished in 1927, and still houses the Shanghai Customs. The No. 14 Bank of Communications building, completed in 1948, is the most recent of these buildings to be completed. Following the foundation of the state, it has been managed by the Shanghai Trade Commission. The rest of the buildings are mostly the headquarters of foreign banks and insurance companies, as well as high-class hotels. For example, No. 1 was the Asia Building, built in 1913; the Nissin Building (also known as the Shipping Building), completed in 1925, was used to house the Japanese Shipping Company. The HSBC Building (also known as the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government Building) was built in 1925. The current East Wind Hotel, which was at first the main British social club in Shanghai, had the longest bar cabinet at 110.7 feet. The then Central Hotel No. 19 is now the Peace Hotel. No. 22, the Sassoon House, was completed in 1929, and is the tallest one in the Bund and part of the Peace Hotel. Nos. 3, 6 and 18 have all been renovated and are now high-end shopping and entertainment venues and are the centres of luxury consumption in Shanghai.

Table 1 shows examples of the deconstruction of information about the representative buildings in the Bund, from a historical perspective.

4. Construction of a Non-Fiction Narrative of the Bund

In order to introduce the history of the Bund, this paper uses a non-fictional approach to create a script that deals with representative buildings. Furthermore, each building in the Bund is linked to this script. In the script, multiple characters are created, taking into account their experiences and situations, and their ‘plight’ is presented from multiple perspectives, which can hold the audience’s attention. The audience can follow the narrative line of this story as it roams through physical space, gaining access to the AR information superimposed on the building, thus enabling a ‘real-time’ and ‘experiential’ audience reception mode in real space. This script, in turn, contributes to the construction of a three-dimensional, multi-temporal mode of interactive communication. Overall, to summaries this paper, a non-fictional approach has been used to create a script, based on the historical context of the Bund (

Appendix A).

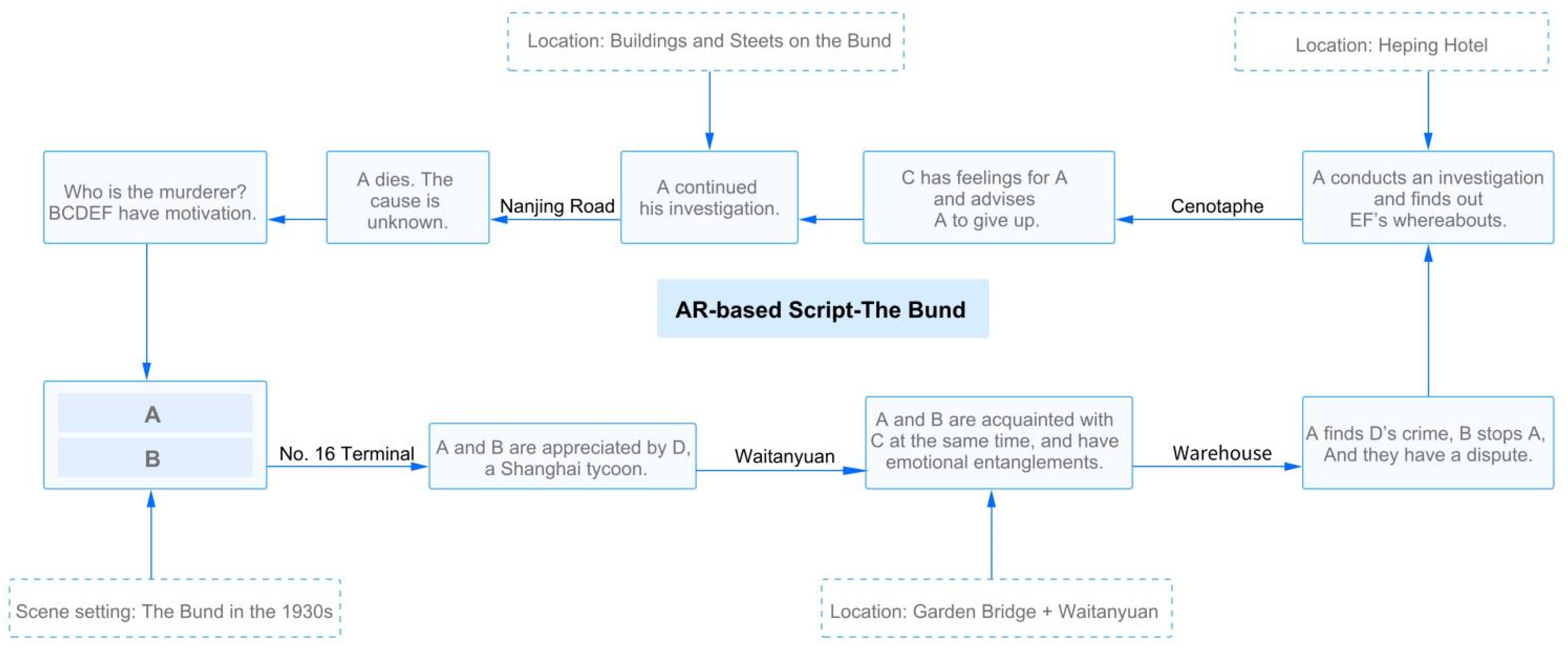

As shown in

Figure 1, the script was created using a non-fiction writing technique. At the same time, the existing historical buildings in the Bund are outlined in the context of the development of Shanghai after the opening of the Bund. Moreover, an aerial narrative line is used to connect the relationships between specific buildings in the scene. Not only does it follow the timeline and advance the plot in a non-fictional way, but it also incorporates narrative methods, such as voice-overs and flashbacks. In addition, the script has been written with the temporal dimension in mind. Specifically, in order to break the continuity of time and space, interactive plotting and montage effects are used after the narrative content of the sub-chapters.

For example,

Upon discovering the weapons, a series of questions popped into protagonist A’s head.” Who are these weapons for? Why am I here? I’m just an ordinary college student who got a job because I followed D to Shanghai.” A feels a deep sense of loss because A’s education requires A to stay away from these weapons, but A also knows that they are the very means by which D makes his money.

In this passage, the weapon in front of A is referred to as A’s clue, which the author uses to enable A to switch in time and space between the past and the present context of his life. The temporal montage effect created between the two segments, as well as the trajectory of virtual and real life, provides a hint for A to make ‘some kind of choice’. In contrast to traditional pictorial narratives, content superimposed and enhanced open-ended narratives allow for the creation of panoramic simulations of ‘virtual environments’, depending on the need for scene scripting. The creation of such, more integrated hybrid environments with reality, and an immersive sense of presence, greatly enhances the depth of the content.

On the technical side of creation, given that the object of study, the international architecture of the Bund, spans several kilometres in a realistic setting, the coupling between the differences in location, and the overall narrative structure based on augmented reality, had to be taken into account when creating the narrative script for the scenes in question. According to Gwilt, from a creative perspective, AR creates scenes that bring digital content into physical space, meaning that new meanings can be created for ever-changing places and scenes [

29]. Conceptually, the virtual images superimposed by AR are not intended to mimic the phenomenon of one space being replaced by another, rather they are intended to understand the complex relationships between them.

Table 2 illustrates how the buildings of the Bund and their cultural information are integrated into the script.

As can be seen, the script is based on the history of the Bund, and most of these scenes are not directly visible in the present day. A scholar of cognitive narrative, Ryan introduced the concept of cognitive maps into narratology. This has also facilitated the integration of narratology and geography, expanding the path of narratology to the study of spatial history [

30]. Whereas the characteristics of AR can link the narrative and places more directly and closely. For example, based on this concept, visitors, especially as their knowledge and experience is usually limited to historical contexts, can also view some of the missing content without the need for an interface, through a specialised device (e.g., a mobile phone or a tablet). Instead, the use of AR can “provide concrete visual clues about past events and representations of content, and leave room for the visitor’s imagination” [

31].

Figure 2 shows the historic look of the Shaxun Building, the predecessor of the Heping Hotel, that Cyberverse has attached to it and displayed on the mobile phone interface.

In non-fiction script design, the author chooses the right characters as ‘avatars’ and observes and experiences the development of the narrative from a first-person perspective. The author needs the characters to be present, to feel present and to think in the present. For example, in this study, the author acts as a waiter in Character D’s mansion and observes the various characters in the narrative from their perspective. The audience can also perceive the presence of the author’s thoughts in the development of the narrative. Taken together, this feature of the non-fiction approach gives the narrative scripts in this study a greater sense of feeling. The narrative script in this study has a greater sense of resonance and presence precisely because of the presence of non-fictional creations. It gives the viewer an experience that is usually one of participatory viewing rather than simple information delivery and passive reception. Furthermore it is aligned with AR technology as virtual information is overlaid on the real world. It is conceived as a narrative that can transcend history as well as time and spatial reality.

5. Sustainable Cultural Resources: An Immersive Urban Experience Scene

The integration of new technologies with urban cultural venues has been developed over the years. Guangzhou Daily established a new media technology support center, with the Original Technology Department as the core, to produce content products with timeliness, visibility and immersion, working with the content production team. In 2020, the technical team involved in the production of “VR Takes You Behind the Scenes of the Cantonese Opera”, assisted journalists in filming scenes such as backstage dressing rooms, rehearsal rooms and stages, respectively, using panoramic filming equipment. Taking the dressing room as an example, the dressing room became a virtual reality space under the 360-degree VR lens, as shown in

Figure 3.

Unlike VR, AR allows virtual information to be better associated with landmarks by projecting digital objects into the real environment. These landmarks, in turn, are not only carriers of historical memories, but also of cultural heritage. With the help of AR, the history of the buildings can be presented virtually. Users can also be able to break the limits of physical space and time and learn a wealth of information related to their past lives through multiple devices. For example, the Guangzhou Thirteen Hongs Museum l collaborated with an AR technology company to launch an AR guided tour function in 2018. Visitors can scan the cultural exhibits in the museum through a customised app and listen to an audio guide while viewing digital images of the artefacts on the screen. On the electronic screen, visitors can select their favourite exhibits, adjust them to the right size and position, then take a photo with them. In 2020, the Liangzhu Museum in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, launched an AR glasses tour, giving visitors the additional option to immerse themselves in the past lives of exhibits, rather than being limited to voice or manual tours. At the same time, this AR technology supports offline voice recognition and can also reconstruct historical scenes that cannot be restored during traditional manual and audio tours. As well as museums, AR technology has also been used in the restoration of the Da Shui Fa site. Baidu’s AR technology department connected the old Summer Palace site to the actual site, allowing a ‘complete’ view of the Da Shui Fa through a handheld mobile AR device. On the screen, the original scattered stones and pillars are presented in the form of layers of line sketches. The framework of the building erected amidst the shattered remains is colored in layer by layer. As visitors move around the site, they can see how the Da Shui Fa would have looked from different angles.

However, both exhibits in museums and Dashuifa in the Old Summer Palace are separate cultural sites, and aims to integrate the scattered cultural sites into some open places in the city, such as the Bund in Shanghai. Generally, people’s first impression of Shanghai is of the Bund, as it is the city’s calling card. As the city grows and changes, the Bund itself is also changing. It is well known that the Bund is located on the banks of the Huangpu River in the Huangpu District of Shanghai. Through AR technology, it is possible to show people the past of these buildings and the stories that cannot be told, thus making the intangible cultural meaning of ‘history’ visible. Through the medium of architecture, people can really see what makes the Bund the ‘root of Shanghai’s history and culture’. At present, the way people visit the site is still mainly a sightseeing tour. Most of these people follow a guided tour, and individual tourists are fond of taking photographs. However, all these approaches only allow the visitor to passively accept the city. AR can change this situation. It allows visitors to go from passive to active, exploring each and every sight in the city through a script-like experience. This greatly increases the motivation of visitors, thus increasing their goodwill towards the city and better reflecting its character. In addition, AR has a strong endogenous nature. For a long time, tourists have mostly been sightseeing tourists, and only for the sake of sightseeing. This type of sightseeing has resulted in visitors not having a deep impression of the destination and scenic spots. Compared to a real tour guide, a virtual tour guide created through AR technology is more approachable and interacts more freely with the visitor. In this way, the distance to the visitor is reduced, thus making sightseeing more personal and independent. It is a novel experience that also deepens the visitor’s impression of the destination. In addition, AR is highly realistic. Through the combination of panoramic projection and AR, scenes that cannot be viewed up close, can be highly recreated. All of these interactions can enhance the stickiness of users and bring a constant stream of visitors to the scenic spot. Further, a user evaluation function can be added to the AR system, allowing visitors to give their opinions and comments on the scenic spot. This can promote a better development of the scenic spot and provide better services to visitors, thus enhancing the competitiveness of the tourist destination.

Rooted in the city, its urban cultural resources can be overlooked in the process of urban modernization, which makes it difficult to maintain the city’s historical and cultural contexts [

6]. Through a non-fiction approach, we explore a narrative perspective that combines physical space and cultural context, as well as finding ways to reproduce and present the cultural resources of the city.

As a media, this paper finds that the application of AR technology can enhance the presence of the Bund’s cultural resources and create a new scene, unlike anything the city has seen before. A distinctive feature of media technology since the early days of its development has been that it breaks the obligatory link between information delivery and the shared space [

32]. Different from old media tools, however, technologies such as VR, AR and MR have broken the boundaries between content and audience through interactivity, resulting in thoroughly different sensory experiences. Boundaries are just similar to “the fourth wall” between the theatre stage and the audience. On a proscenium stage, there are generally three walls in the space, but actors and actresses on the stage are prone to imagine a virtual wall to separate the stage from the auditorium that enables them to better immerse themselves in the performance while ignoring the reactions of the audience. By contrast, the audience, if indulged in the performance, tends to ignore the wall. Similarly, in cases such as being fully immersed in the storyline of a movie, or paying too much attention to the movements, routes and operations of a game while ignoring other people and things, people’s minds are already immersed in the world inside the screen although they are physically sitting on the other side of the screen. A screen is similar to a wall connecting another world, through which those in a state of immersiveness seem to enter the other world. People become aware of this wall since they can perceive the existence of boundaries, such as the entrance of the stage and the screens of mobile phones and computers.

Computers have now evolved from tools for content production (mimicking the functions of typewriters, paint brushes, etc.) to equipment that can be used to create, store, distribute information and access all media. Lev Manovich characterized the way computers present media content as “human-computer cultural interface interaction” [

33]. At this time, the user no longer interacts with the computer, but with the culture that it carries. The computer is thus a tool or medium for human interaction with culture, similar to newspapers, magazines and books. A combination of screen and computer has become the main method of rapid access to media information. Reality, framed in a rectangular screen, has clear boundaries, as well as being irreversible and untamperable. Furthermore, only the content presented on the screen is given an essence, being illuminated and thus viewed by people. An AR-based space, by contrast, is one in which there is barely the slightest visual blind spot for the viewer. As such, they can be seen as being ‘pulled in’ from outside the story or event. In other words, there is an immersion of the viewer’s mind in the space constructed by the media, and the perceptual boundaries between the physical world and the media space become blurred. In previous technological environments, such media spaces were more often presented on a screen, in people’s conscious imagination. In contrast, technologies such as AR and VR allow for the direct construction of a space that emphasises the viewer’s first perspective of perception and experience. Within it, people can interact directly with the environment constructed by VR technology, rather than through a third perspective. The development of networked information technologies has made both digital presence and remote presence possible, in addition to the physical corporeal presence. Human perception through the direct senses is weakened and the ‘innate instrumental perceptual experience’ is replaced by technological perception [

34]. Technologies such as VR and MR are similar to building an immersive environment, that is to say building a reality that is closer to the human body’s most primal sensory experiences. When people wear devices with extended sensory capabilities, the sense of ‘being there’ acts directly on the body’s perceptual system, allowing people to consciously include their own bodily feelings and life experiences in their associations. Humans can feel the presence of their bodies through the perception and practice of the spaces constructed by the media technology system, realising the ‘re-perception’ of the body in the process of communication. In this case, a virtual body can exist in the constructed space as an ‘avatar’ of the real body. This is a new way of presenting the subject [

35].

In the age of mass media, due to the existence of communication, many things are actually inaccessible to people on the spot, so they act more as observers of the scene. At the same time, their bodies have difficulty in accessing the communication network directly and achieving live communication, and they can only rely on symbols to connect with other subjects. Thus, it is necessary to create a sense of reality and immersion through imagination. The “sensory hegemony of the visual centre” has changed, as the incarnation’s presence in the hybrid space relies more on various interactive activities [

36]. This also characterises the multisensory, immersive interaction of scenes in AR-based spaces.

The words and phrases of written language take the form of abstract symbols that have existed independently of humans from the very beginning. Human perceptions and ideas are systematically presented through media. In the era of images, the three-dimensional world is condensed onto a two-dimensional screen. This is then converted by the eye into pulses with specific frequencies that activate the relevant image information stored on biomolecules in the brain, allowing the brain to perceive the information more directly. In the age of immersive communication, the body is “immersed” in the communication field as the interface for information interaction. The original text- and image-oriented communication model is weakened and replaced by an immersive communication model centred on real-time human participation and aided by the activation of sensory resonance. Thereby, in the era of interpersonal interactive spoken communication, new analogue scenarios characterised by “voice narration” are created. The immersion model of communication echoes the ‘dialogic’ model of communication advocated by Idealism by changing the narrative style of the media and diminishing the function of symbols as media. The presentation of symbols in a unified form maintains the communicative paradigm of the text, while eliminating the differences and homogeneity of the narrator’s personal image. The logic of this idea is that once information is presented in symbolic form, the value of dialogue is reduced. Thus, once the simulated scenario dominated by ‘voice narration’ is restored, information with the individual as the subject of communication will be represented. Instead, the human figure will be restored in a virtual space without borders, with diachronic and synchronic coexistence.

Linear or non-linear narratives based on traditional media are characterized by a flattening of the structure. In contrast, this AR technology-based narrative, through non-fiction offers a new spatial dimension. The guide centred ‘closed-loop’ narrative text is broken, and the original one-way story structure becomes a multi-path/multi-exit tour with each ‘approach’ and ‘interaction’ of the visitor. This immersive interaction can transform the visitor’s cultural experience of the city, and the underlying cultural messages can be uncovered. One of the things that is often missing from urban cultural resources is how to bring the historical stories of what happened on the sites more directly to the visitor. This would facilitate the integration of the physical spaces in the city with the inner stories, thus strengthening the local cultural identity. The concept of narrative in a non-fictional way can help to integrate scattered cultural resources. Connecting these cultural resources located in different parts of the city in an orderly manner brings the cultural value of the city into sharper focus.