Ethnobotany in Iturbide, Nuevo León: The Traditional Knowledge on Plants Used in the Semiarid Mountains of Northeastern Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

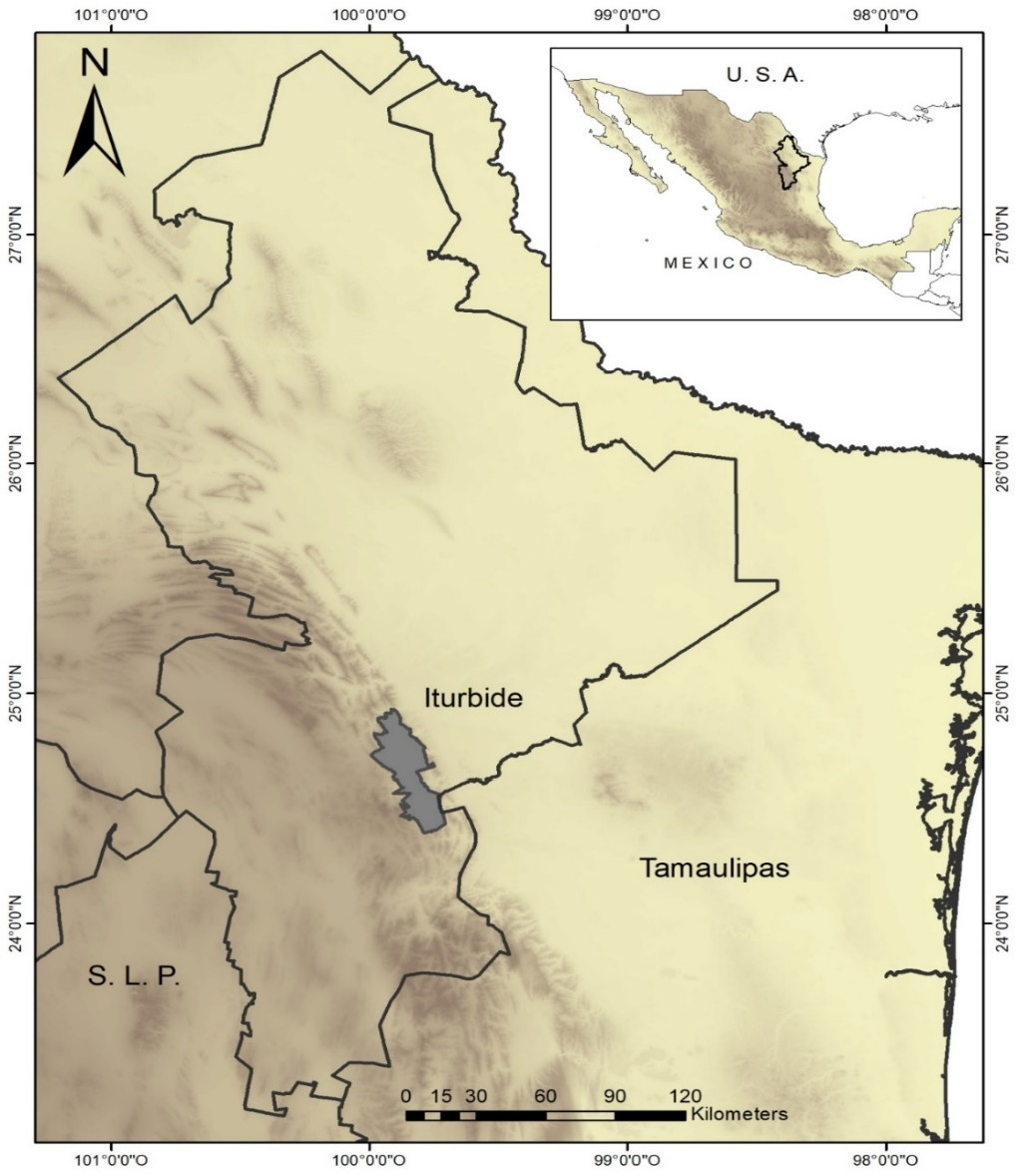

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Field Work and Interviews

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

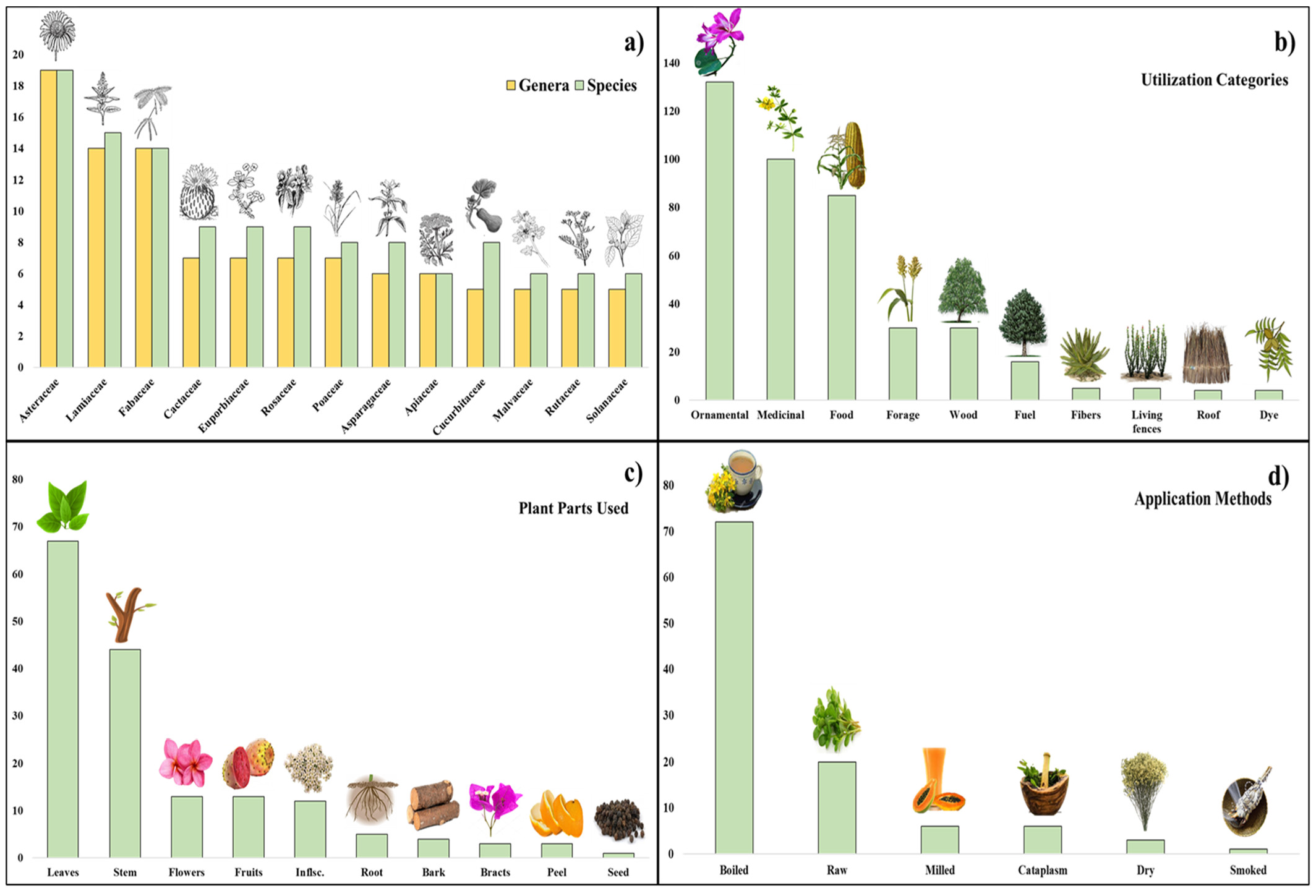

3.1. Taxa Diversity, Origin and Life Forms

3.2. Ethnobotanical Uses

3.2.1. Ornamental

3.2.2. Medicinal

3.2.3. Food

3.2.4. Forage

3.2.5. Construction and Fuel

3.2.6. Fibers

3.2.7. Live Fences

3.2.8. Dye

3.2.9. Roof

3.3. Quantitative Ethnobotanical Indices (IFC, UVI, FL)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scientific Name | Common Name | Uses (System) | Part Used | Method of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACANTHACEAE | ||||

| Hypoestes phyllostachya Baker, E, EE25323 | Paleta de pintor | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Beloperone gutatta Brendegee, N, EE25325 | Camarón | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| ACERACEAE | ||||

| Acer negundo L., EE25383 | Maple | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public parks and private gardens |

| ACTINIDIACEAE | ||||

| Actinidia deliciosa (A.Chev.) C.F.Liang & A.R.Ferguson, E, EE25447 | Kiwi | Food | Fruit (pulp) | Raw |

| ADOXACEAE | ||||

| Sambucus canadensis L., N, EE25384 | Sauco | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public parks and private gardens |

| Medicinal (respiratory system) | Inflorescences and flowers | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| AMARANTHACEAE | ||||

| Amaranthus palmeri S.Watson, N, EE25326 | Quelite | Food | Leaves and inflorescences (young) | Cook with oil or raw (previously disinfected with chlorine in water) |

| Forage | Whole plant | Raw | ||

| Beta vulgaris subsp. adanensis (Pamukç.) Ford-Lloyd & J.T. Williams, E, EE25448 | Betabel | Food | Leaves | Boiled, liquate |

| medicinal (gastrointestinal system), detoxify the gut | Leaves | Raw, boiled or cooked | ||

| Dye | Roots | Raw, squeezed | ||

| Beta vulgaris L. var. cicla L., E, EE25371 | Acelga | Food | Leaves | Raw, boiled or fried. |

| Chenopodium ambrosioides L., N, EE25324 | Epazote | Food | Leaves, inflorescences and flowers | Boil or cook with beans (to add flavor) |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), eliminate intestinal worms | Leaves, stems, inflorescences and flowers | Boiled, drink the solution | ||

| Condiment | Leaves and stems | Dried, crushed, added to flavor the food | ||

| Forage | Whole plant | Raw | ||

| Spinacia oleracea (L.) E.H.L.Krause, E, EE25449 | Espinaca | Food | Leaves | Raw (previusly disinfected with chlorine in water) |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system) | Leaves | Liquate, raw, to eliminate amoeba | ||

| AMARYLLIDACEAE | ||||

| Crinum asiaticum L., E, 25450 | Lirio listado | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Clivia miniata (Lindl.) Bosse, E, EE25451 | Clivia | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| ANACARDIACEAE | ||||

| Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl., N, EE25452 | Cuacharalate | Medicinal (dermic system), antiseptic, antibiotic | Bark | Boiled, used as cataplasm, wound washing |

| Mangifera indica L., E, EE25454 | Mango | Food | Fruit | Raw, mixed with green salads |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Rhus trilobata Nutt., N, EE25455 | Lantrisco, jobo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Construction | Trunks and branches | Dried, to make columns of houses, tools and fuel | ||

| Rhus virens Lindh. ex A. Gray, N, EE25456 | Lantrisco | Construction of tools and fuel | Trunks and branches | Dried, to make columns of houses, tools and fuel |

| Forage | Leaves | Raw | ||

| Schinus molle L., E, EE25457 | Pirul | Rites (soul cleansing) and religion | Small branches and leaves | Leaves are rubbed all over the individual’s body while praying |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| ANNONACEAE | ||||

| Annona muricata L., N, EE25453 | Guanábana | Food | Fruit | Raw or liquid to make fruit drinks |

| APIACEAE | ||||

| Apium graveolens L., E, EE25327 | Apio | Food | Leaves | Raw, in salads |

| Medicinal (blood system), low cholesterol | Leaves and stems | Raw | ||

| Coriandrum sativum L., EE25328 | Cilantro | Food (condiment) | Leaves | Raw or cooked in broth |

| Cuminum cyminum L., E, EE25329 | Comino | Food (condiment) | Seeds | Cooked with rice and meat |

| Daucus carota L., E | Zanahoria | Food | Root | Raw or cooked with different vegetables |

| Daucus carota L., E, EE25330 | Hierba del sapo | Medicinal (urinary system), dissolve kidney stones | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Eryngium heterophyllum Hemsl. & Rose, N, EE25504 | Perejil | Medicinal (blood system), low cholesterol and triglycerides | Root | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Food | Leaves and stems | Raw or cooked with different vegetables | ||

| Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss, E, EE25331 | Medicinal (urinary system) | Leaves | Prevents bladder infections | |

| Medicinal (blood system) | Leaves | Purifies the blood | ||

| APOCYNACEAE | ||||

| Cascabela thevetia (L.) Lippold, E, EE25503 | Cascabel | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Plumeria rubra L., N | Ramo de novia | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Vinca minor L., E, EE25220 | Teresita | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private and public gardens |

| ARACEAE | ||||

| Spathiphyllum wallisii Regel, N, EE25502 | Cuna de Moisés | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Anthurium magnificum Linden, N, EE25501 | Anturio, lampazo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Zantedeschia aethiopica (L.) Spreng., E, 25500 | Alcatraz | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| ARECAECEAE | ||||

| Brahea berlandieri (Kunth) Mart., N, EE25499 | Palmito | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Rites | Leaves | Ornaments in floral bouquets | ||

| Construction | Leafs | Roofs of houses and cabins | ||

| Cocos nucifera L., E, EE25385 | Coco | Food | Fruit | Raw pulp and its water, to make candies |

| Washingtonia filifera (Linden ex André) H.Wendl. ex de Bary, N, EE25386 | Palma | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Construction, roofs | Leaves | Dried | ||

| ASPARAGACEAE | ||||

| Agave lechuguilla Torr., N, EE25251 | Lechugilla | Healthy hair | Root | Milled, raw, used as shampoo |

| Fibers | Leaves | Leaves divided into multiple fibers used to make woven products | ||

| Food | Root | Boiled and fermented (to prepare alcoholic beverages) | ||

| Living fences | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Agave americana L. var. americana, N, EE25251b | Maguey | Food | Root | Agua miel (sap), raw or cooked to make syrup |

| Food (quiote) | Peduncle | Cooked in a well with hot stones and firewood, covered for 24 h | ||

| Food | Flowers | Cooked | ||

| Food | Root | Boiled and fermented (to prepare alcoholic beverages) | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Construction | Peduncle (dry) | Livestock keeper | ||

| Living fences | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Agave aff. scabra Ortega, N, EE25251c | Maguey, bronco | Food (quiote) | Peduncle | Cooked in a well with hot stones and firewood, covered for 24 h |

| Fibers | Leaves | Used to make ties | ||

| Living fences | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Living fences | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Asparagus setaceus Kunth, E, EE25332 | Hoja elegante | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Dasylirion berlandieri S. Watson, N, EE25253 | Sotol | Food | Root | Boiled and fermented (to prepare alcoholic beverages) |

| Religious rites | Leaves (base) | With the base of the leaves, structures similar to flowers are made that adorn the main square and streets in celebration of the patronal feast of San Pedro | ||

| Polianthes tuberosa L., N, EE25254 | Nardo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Sansevieria trifasciata Prin., E, EE25498 | Lengua de suegra | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private and public gardens |

| Yucca filifera Chabaud, N, EE25155 | Palma china | Food | Flowers (called chochas) | Raw, collected before opening and the reproductive structures are removed so that when cooking they do not make the food bitter |

| Food | Fuit (called dátiles) | Raw | ||

| Yucca filifera Chabaud, N, EE25155 | Palma china | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Raw | ||

| Yucca treculeana Carrière, N, EE25155b | Palma samandoca | Food | Flowers (called chochas) | Raw, collected before opening and the reproductive structures are removed so that when cooking they do not make the food bitter |

| Live fences | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| ASPHODELACEAE | ||||

| Kalanchoe blosfeldiana Poelln., E, EE25152 | Brujita | Ornamental, for its beautiful fleshy leaves | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Kalanchoe digremontiana Raym.-Hamet & H. Perrier, E, EE25333 | Urania | Medicinal (endocrine system), anti-inflamatory | Sap | Raw, drink the sap |

| Medicinal (gastric system), heal gastrointetinal problems | Leaves (pulp) | Raw, milled, drink the sap | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| ASTERACEAE | ||||

| Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt., N, EE25256, EE25334 | Estafiate | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), diarrhea, flatulences | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink infusion |

| Baccharis salicifolia Nutt, N, EE25258 | Jara, jarilla | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), diarrhea, flatulences | Leaves and stems | Cut into pieces, boiled in water, drink the solution |

| Calea oliveri B.L.Rob. & Greenm., N, EE25368 | Ámbula | Medicinal (nervous system), insomnia | Leaves | Boiled in water, drink the solution |

| Chrysactinia mexicana A. Gray, N, EE25370 | Hierba de San Nicolás | Medicinal (reproductive system), aphrodisiac | Leaves | Boiled in water, drink the solution |

| Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat., EE25222 | Crisantemo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Conyza filaginoides (DC.) Hieron, N, EE25497 | Simonillo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), diarrhea, colic | Leaves and stems | Boiled in water, drink the solution | ||

| Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes and cancer | Leaves and stems | Boiled in water, drink the solution | ||

| Dahlia coccinea Cav., N, EE25388 | Dalia (the representative plant of Mexico) | Ornamental, by its showy and big inflorescences with red external flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Flourensia cernua DC., N, EE25387 | Hojasé | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), constipation | Leaves | Boil only 3–4 leaves, very astringent effect and very bitter taste |

| Gnaphalium viscosum Kunth, N, EE25389 | Gordolobo | Medicinal (respiratory system), cough, throat pain | Stems, leaves, inflorescences and flowers | Boiled in water, drink the solution |

| Grindelia inuloides Willd. var. inuloides, N, EE25390 | Árnica | Medicinal (skeletal-muscular system), external wounds | Leaves and inflorescences | Boiled in hot water, drink the solution |

| Gutierrezia sarothrae (Pursh) Britton & Rusby, N, EE25496 | Amargosa | Medicinal (broken bones), | Leaves | Used as plaster (glutinous stems, sticky) |

| Gymnopserma glutinosum Less., N, EE25369 | Marica | Fibers | Branches | Dried, they |

| Household items | Leaves and stems | Dried, intertwined, tied and attached to a stick to make homemade brooms | ||

| Helianthus annuus L., N, EE24495 | Girasol | Forage | Whole plant | Raw |

| Lactuca sativa L., E, EE25391 | Lechuga | Food | Leaves | Raw, previosly disinfected with chlorine |

| Machaeranthera tanacetifolia (Kunth) Nees, N, EE25494 | Árnica | Medicinal | Leaves and inflorescences | Boiled, solution used as cataplasm |

| Matricaria recutita L., E, EE25493 | Manzanilla | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), colic, stomach ache | Leaves | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Parthenium hysterophorus L., N, EE25492 | Amargoso | Mosquito repellent | Whole plant (dry) | Burning in the yard, smoke produced repels insects and other pests |

| Household items | Leaves and stems | Dried, intertwined, tied and attached to a stick to make homemade brooms | ||

| Tagetes lucida (Sweet) Voss, N, EE25491 | Yerbanís | Beverage | Leaves, stems, inflorescences and flowers | Boiled, drink as tea |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), stomach ache, colic, ulcer | Leaves, stems, inflorescences and flowers | Boiled, drink as tea | ||

| Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch.Bip., E, EE25490 | Altamisa | Mosquito repellent | Whole plant | Alive, inside the house |

| Medicinal (gastric system), stomach ache | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the solution | ||

| Taraxacum officinale (L.) Weber ex F. H.Wigg., E, EE25489 | Diente de león | Food | Leaves | Raw (previously disinfected with chlorine) |

| Forage | Whole plant | Raw | ||

| Trixis californica Kellogg, N, EE25488 | Árnica | Medicinal | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Zinnia elegans L., N, EE25335 | Cartulina | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private and public gardens |

| BALSAMINACEAE | ||||

| Impatiens hawkeri W. Bull, E, EE25219 | Belén | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| BEGONIACEAE | ||||

| Begonia gracilis Kunth, N, EE25236 | Begonia | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| BIGNONIACEAE | ||||

| Chilopsis linearis (Cav.) Sweet, N, EE25487 | Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private and public gardens | |

| Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth, N, EE25218 | Tronadora, San Pedro | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| BORAGINACEAE | ||||

| Cordia boisssieri A. DC., N, EE25157 | Anacahuita | Medicinal (respiratory system), pneumonia | Flowers and fruit (pulp) | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Forage | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Ehretia anacua (Terán & Berland.) I. M. Johnst., N, EE25163 | Anacua | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| BRASSICACEAE | ||||

| Brassica oleracea L., E, EE25486 | Repollo | Food | Leaves | Raw or cooked with other vegetables. |

| Lepidium peruvianum G. Chacón, E, EE25336 | Raíz peruana | Medicinal (gastrointestinal, endocrine and urinary systems) | Root | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Rorippa officinale R. Br., E, EE25485 | Berro | Medicinal (endocrine system), protstate problems | Leaves and stems | Boiled, eat and drink infusion |

| Food | Leaves | Raw (previusly disinfected with chlorine in water) or cooked with other vegetables | ||

| Raphanus sativus L., E, EE25484 | Rábano | Food | Root | Raw, in salads |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), asthma problems | Root | Raw, pulp | ||

| Medicinal (blood system), lower blood pressure | Root | Raw, pulp | ||

| BROMELIACEAE | ||||

| Ananas comosus (L.) Merr., E, EE25483 | Piña | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Food | Fruit juice | Meat tenderizer | ||

| Hechtia podantha Mez, N, EE25392 | Guapilla | Fibers | Leaves | Leaves divided into multiple fibers used to make woven products (ties) |

| Tillandsia usneoides (L.) L., N, EE25231 | Paixtle | Religious rites | Leaves | Dried, decorate the christmas tree |

| Manufacture of articles | Leaves | To make pillows | ||

| BUDDLEJACEAE | ||||

| Buddleja cordata ssp. tomentella (Standl.) E.M.Norman, N, EE25393 | Tepozán | Medicinal (skeletal-muscular system), general pain | Leaves | Boiled in water, solution used as cataplasm |

| CACTACEAE | ||||

| Cylindropuntia imbricata (Haw.) F.M.Knuth, N, EE25246 | Coyonoxtle | Medicinal (skeletal-muscular system), breaks and fissures of bones | Stems and pulp | Raw, use as cataplasm, smear the pulp on the injured area and bandage |

| Cylindropuntia leptocaulis (DC.) F.M.Knuth, N, EE25246b | Tasajillo | Medicinal (endocrine system) cancer | Stems and pulp | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Echinocactus platyacanthus Link & Otto, N, EE25482 | Biznaga burra | Food | Stems and pulp | Cooked with piloncillo (brown sugar) to make candies |

| Hylocereus undatus (Haw.) Britton & Rose, N, EE25377 | Pithaya | Food | Fruit | Raw, blended with water to make drinks |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Dye | Fruit | Raw, squeezed | ||

| Lophophora williamsii (Lem. ex Salm-Dyck) J.M. Coult., N, EE25394 | Peyote | Spiritual, religious | Whole plant | Raw, eaten in pieces or blended in water and drink the potion |

| Medicinal (skeletal-muscular system) | Whole plant or cut into pieces inside alcohol and mixed with marijuana (Cananbis sativa) | Raw, cataplasm, rubbed on sore joints | ||

| Medicinal (nervous system), insomnia | Pieces of plant | Raw, eaten in pieces or blended in water and drink the potion | ||

| Mammillaria heyderi Muehlenpf., N, EE25395 | Chilitos | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Myrtillocactus geometrizans (Mart. ex Pfeiff.) Console, N, EE25396 | Garambuyo | Living fences | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill., N, EE25397 | Nopal sin espina | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Forage | Stems (cladodes) | Raw, cut into pieces and scorched (to remove thorns) | ||

| Food | Stems (cladodes) and fruit | Peeled and cut into pieces, raw or cooked, fruit eaten raw | ||

| Medicinal (endocrine system), low cholesterol | Stems | Raw, cut into pieces and eat | ||

| Opuntia lindheimeri Engelm., N, EE25249 | Nopal | Forage | Stems (cladodes) and fruit | Raw, cut into pieces and scorched (to remove thorns), fruits eaten raw |

| Food | Stems | Raw | ||

| Medicinal (endocrine system), low cholesterol | Stems | Raw, stem pulp | ||

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), improve digestion | Stems | Raw, stem pulp, liquefied | ||

| CANNABACEAE | ||||

| Celtis leavigata Willd., N, EE25233b | Palo blanco | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Celtis pallida Torr., N, EE25233 | Granjeno | Food | Fruit | Raw or boiled to make syrup |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| CANNABINACEAE | ||||

| Cannabis sativa L., E, EE25481 | Mariguana | Medicinal (skeletal-muscular system) | Female inflorescences and leaves into alcohol and mixed with peyote | Cataplasm, rubbing on sore joints |

| Recreational, playful use | Female inflorescences | Smoked | ||

| CANNACEAE | ||||

| Canna indica L., E, EE25240 | Coyol | Ornamental, for its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| CAPRIFOLIACEAE | ||||

| Lonicera japonica Thunb., E, EE26167 | Madreselva | Ornamental, for the delicious aroma of its flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| CARICACEAE | ||||

| Carica papaya L., N, EE25480 | Papaya | Food | Fruit | Raw or in fruit salads |

| CARYOPHYLLACEAE | ||||

| Dianthus caryophyllus L., E, EE25224 | Clavel | Ornamental, for its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Dianthus deltoides L., E, EE25440 | Clavelina | Ornamental, for its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Gypsophila paniculata L., E, EE25441 | Ilusión | Ornamental, for its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| COMMELINACEAE | ||||

| Commelina coelestis Willd., N, EE25442 | Hierba del pollo | Ornamental, for its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| COSTACEAE | ||||

| Costus igneus N. E. Br., E, EE25443 | Insulina | Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| CONVOLVULACEAE | ||||

| Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam., N, EE25444 | Camote | Food | Root | Rosted or boiled |

| Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth, N, EE25445 | Manto de la virgen | Ornamental, for its beautiful purple flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| CRASSULACEAE | ||||

| Echeveria simulans Rose, N, EE25446 | Siempreviva | Ornamental, for its beautiful fleshy leaves | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (ophthalmic system), red eyes, irritated eyes | Sap | Eye drops | ||

| Sedum diffusum S. Watson, N, EE25437 | Chismes | Ornamental, for its beautiful fleshy leaves | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (ophtlmic system), red eyes, irritated eyes | Sap | Eye drops | ||

| Sedum palmeri S. Watson, N, EE25438 | Deditos | Ornamental, for its beautiful fleshy leaves | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| CUCURBITACEAE | ||||

| Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai, E, EE25151 | Sandía | Food | Fruit | Raw, cut into pieces |

| Forage (pigs) | Fruit peel | Raw | ||

| Cucumis anguria L., E, EE25364 | Pepinillo | Food | Fruit | Boiled into brine |

| Forage | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Cucumis melo L., E, EE25365 | Melón | Food | Fruit | Raw, cut into pieces |

| Forage (pigs) | Fruit peel | Raw | ||

| Cucurbita ficifolia Bouché, E, EE25366 | Chilacayote | Food | Fruit | Boiled in water with sugar to make candies |

| Forage | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Food | Fruit | Cooked with other vegetables | ||

| Cucurbita moschata Duchesne, N, EE25367 | Calabaza | Food | Fruit | Cooked or boiled in water with sugar to make candies |

| Forage | Leaves | Raw | ||

| Cucurbita pepo L., N, EE25439 | Calabaza | Food | Fruit | Cooked |

| Food | Seeds | Raw, dried, toasted and salty | ||

| Forage | Leaves and fruit | Raw | ||

| Luffa aegyptiaca Mill., E, EE25435 | Estropajo | Fibers | Inner part of dried fruit | To wash dishes or to carve skin for bathing |

| Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw., N, EE25479 | Chayote | Food | Fruit | Raw, cut into pieces or boiled |

| CUPRESSACEAE | ||||

| Cupressus arizonica Greene, N, EE25153 | Cedro | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Furniture | Wood | Dried | ||

| Religious rites | Sap (resin) | Used as incense during religious prayers | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried to make columns and beams of houses | ||

| Cupressus lousitanica Mill., E, EE25153a | Ciprés | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Furniture | Wood | Dried | ||

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried to make columns and beams of houses | ||

| Cupressus sempervirens L., E, EE25378 | Pincel | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried to make columns and beams of houses | ||

| Juniperus flaccida Schltdl., N, EE25436 | Táscate | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried to make columns and beams of houses | ||

| Thuja occidentalis L., E, EE25172 | Tuya | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| CYCADACEAE | ||||

| Cycas revoluta Thunb., N, EE25434 | Chamal, cica | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Dioon edule Lindl., N, EE25375 | Chamal | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Food | Seeds | To make flour and tortillas | ||

| EBENACEAE | ||||

| Diospyros palmeri Eastw., N, EE25432 | Chapote | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Forage | Fruit | Raw, for cattle, sheeps, goats and pigs | ||

| Fuel | Trunks and branches | Dried | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried to make columns and beams of houses | ||

| EQUISETACEAE | ||||

| Equisetum laevigatum A. Braun, N, EE25433 | Cola de caballo | Medicinal (urinary system), kidney pain | Stems | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| EUPHORBIACEAE | ||||

| Acalypha hederacea Torr., N, EE25173 | Hierba del cáncer | Medicinal (endcorine system), cancer | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Forage | Whole plant | Raw | ||

| Croton suaveolens Torr., N, EE25478 | Salvia | Medicinal (blood system), anemia | Leaves and stems | Boiled in water, drink the infusion |

| Euphorbia pulcherrima Willd. ex Klotzsch, N, EE25156 | Noche buena | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Euphorbia dentata Michx., N, EE25261 | Golondrina | Medicinal (respiratory system), sinusitis | Leaves and stems | Boiled in water, infusion used as nasal drops |

| Euphoria milii Des Moul., E, EE25261b | Corona de Cristo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Jatropha dioica Sessé, N, EE25431 | Sangre de Drago | Medicinal (dermatologic system), hair growth, fungi | Milled, the pulp used as shampoo | |

| Medicinal (gastric system), harden the gums | Leaves and stems | Milled, chew and spit out the pulp | ||

| Ricinus communis L., E, EE25159 | Higuerilla | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Sapium sebiferum (L.) Roxb., E, EE25164 | Sapium | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Tragia ramosa Torr., N, EE25363 | Mala mujer | Medicinal (urinary system), kidney diseases | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| FABACEAE | ||||

| Arachis hypogaea L., E, EE25429 | Cacahuate | Food | Seeds | Raw |

| Forage | Leaves | Raw | ||

| Bauhinia purpurea L., N, EE25225 | Pata de vaca | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system) | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Calliandra conferta A.Gray, N, EE25430 | Charrasquillo | Forage | Leaves and fruit | Raw |

| Cercis canadensis L., N, EE25165 | Duraznillo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Cicer arietinum L., E, EE25379 | Garbanzo | Food | Seeds | Cooked |

| Erythrostemon mexicanus (A. Gray) Gagnon & G. P. Lewis, N, EE25229 | Potro | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Eysenhardtia texana Scheele, N, 25477 | Palo azul | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Lens culinaris Medik, E, EE25428 | Lenteja | Food | Seeds | Cooked |

| Pachyrhizus erosus (L.) Urb., N, EE25476 | Jícama | |||

| Phaseolus vulgaris L., N, EE25475 | Frijol | Food | Seeds | Cooked |

| Pisum sativum L., E, EE25474 | Chícharo | Food | Seeds | Cooked |

| Prosopis glandulosa var. torreyana (L.D.Benson) M.C.Johnst., N, EE25473 | Mezquite | Construction | Trunks and branches | Dried to make columns and beams of houses |

| Fuel | Trunks and branches | Charcoal | ||

| Forage | Leaves and fruit | Raw | ||

| Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Wight & Arn., N, EE25234 | Huizache | Construction | Trunks and branches | Dried |

| Fuel | Trunks and branches | Charcoal | ||

| Forage | Leaves and fruit | Raw | ||

| Vicia faba L., E, EE25238 | Haba | Food | Seeds | Cooked |

| FAGACEAE | ||||

| Quercus virginiana Mill., N, EE25166 | Encino | Construction | Wood | Dried to manufacture furniture and household goods |

| Forage | Seeds (called bellotas) | Raw | ||

| Fuel | Wood | Dried, cut into pieces | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Quercus canbyi Trel., N, EE25427 | Encino | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Construction | Wood | Dried to manufacture furniture, household goods and columns and beams of houses | ||

| Forage | Seeds (called bellotas) | Raw | ||

| Fuel | Wood | Dried, cut into pieces | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried to manufacture furniture, household goods and columns and beams of houses | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Quercus polymorpha Schltdl. & Cham., N, EE25426 | Encino | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Forage | Seeds (called bellotas) | Raw | ||

| Fuel | Wood | Dried, cut into pieces | ||

| Construction | Wood | To manufacture furniture and household goods | ||

| FOUQUERACEAE | ||||

| Fouquieria spelendens Engelm., N, EE25380 | Ocotillo, albarda | Living fences | Stems | Stems are cut and planted in rows, eventually producing root and leaves (living fences) |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| GERANIACEAE | ||||

| Pelargonium hortorum L.H. Bailey, E, EE25227 | Geranio | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| GESNERIACEAE | ||||

| Tulipa gesneriana L., E, EE25472 | Tulipán | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| HYDRANGEECEAE | ||||

| Hydrangea macrophylla (Thunb.) Ser., E, EE25471 | Hortensia | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| JUGLANDACEAE | ||||

| Carya illinionensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch, N, EE25168 | Nogal | Forage | Leaves | Raw |

| Food | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried | ||

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Medicinal (dermic system), hair dye | Bark | Boiled in water, wash hair with solution | ||

| Carya myristiciformis (F. Michx.) Nutt. ex Elliott, N, EE25470 | Nogal | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Medicinal (dermic system), hair dye | Bark | Boiled in water, wash hair with solution | ||

| Juglans major (Torr.) A. Heller, N, EE25469 | Nogal de nuez encarcelada | Forage | Leaves | Raw |

| Food | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Construction | Wood | Dried | ||

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Medicinal (dermic system), hair dye | Bark | Boiled in water, wash hair with solution | ||

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), colics | Leaves | Boiled in water | ||

| LAMIACEAE | ||||

| Hedeoma drummondii Benth., N, EE25468 | Poleo | Medicinal (nervous system), to fall asleep | Whole plant | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Lavandula angustifolia Mill., E | Lavanda | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Marrubium vulgare L., E, EE25424 | Marrubio | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system) | Leaves | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion, chew and swallow leaves and stems | ||

| Melissa officinalis L., E, EE25425 | Toronjil | Ornamental, for its delicious aroma and to repel mosquitoes | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), colics | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Mentha piperita L., E, EE25241 | Yerbabuena | Medicinal (respiratory system), cough | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion, chew and swallow leaves and stems |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), fever and cold | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Mentha spicata L., E, EE25241b | Yerbabuena | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), spasms | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), flu and asthma | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Monarda citriodora var. austromontana (Epling) B.L.Turner, N, EE25381 | Poleo cabezón, betónica | Medicinal (respiratory system), cough | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion, chew and swallow leaves and stems |

| Medicinal (nervous system), to fall asleep | Leaves | Dried, put a piece of branch under the pillow at night | ||

| Ornamental, for its delicious aroma and beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Ocimum basilicum L., E, EE25242 | Albahaca | Medicinal (nervous system), used against insomnia, to fall asleep | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Religious rites | Whole plant | Part of the flower bouquets used in pilgrimages | ||

| Origanum majorana L., E, EE25257 | Orégano | Food (condiment) | Leaves | Dried, added to broths and soups |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough and cold | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Plectranthus coleoides Benth., E, EE25362 | Vaporú | Medicinal (respiratory system), cough | Leaves and stems | Milled, mixed with glycerine and spread on the chest and nostrils |

| Religious rites | Whole plant | Dried, milled, used as incense | ||

| Ornamental, by its delicious aroma and beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Poliomintha longiflora A.Gray, N, EE25259 | Orégano de montaña | Food (condiment) | Leaves and stems | Dried, added to broths and soups |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough, throat pain | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers and aroma | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Rosmarinus officinalis L., E, EE25382 | Romero | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system) colics | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), nasal congetion | Stems, leaves and flowers | Cut into pieces, boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers and aroma | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Condiment | Leaves | Dried, added to flavor the food | ||

| Scutellaria sp., N, EE25422 | Mirto | Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers and aroma | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Teucrium cubense L., N, EE25423 | Verneba | Medicinal (fever) | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Thymus vulgaris L., E, EE25360 | Tomillo | Medicinal (respiratory system), cough and expectorant | Leaves and stems | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Medicinal (dermic system), dermic infections | Leaves | Boiled, use as cataplasm | ||

| Food (condiment) | Leaves and stems | Dried, add to stews, soups and broths | ||

| LAURACEAE | ||||

| Cinnamomum verum J.Presl., E, EE25361 | Canela | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), stomach pain, vomit | Bark | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough and throat pain | Bark | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Bark | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Medicinal (blood system), improve blood circulation | Bark | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Litsea glauscecens Kunth, N, EE25359 | Laurel | Food (condiment) | Leaves | Dried, add to stews, soups and broths |

| Ornamental, by its showy green stems | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Persea americana Mill., N, EE25170 | Aguacate | Food | Fruit | Raw, used in multiple ways |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), asthma | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Medicinal (circulatory system), arterial hypertension | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Persea podadenia S. F. Blake, N | Salsafrás | Medicinal (circulatory system), anemia | Bark | Cut into pieces, boiled, drink the infusion |

| LILIACEAE | ||||

| Allium cepa L., E, EE25358 | Cebolla | Food | Stem | Raw or boiled |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough, asthma, flu | Stem | Boiled, drink the infusion along with honey bee | ||

| Medicinal (circulatory system), improve blood circulation | Stems | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Allium sativum L., E, EE25421 | Ajo | Medicinal (circulatory system), low cholesterol, improve circulation | Stems | Boiled, drink the infusion, raw, cut into pieces, milled |

| Medicinal (dermic system), dermic wounds | Cloves | Ground garlic cloves, the pulp is smeared on the wound | ||

| Medicinal (auditive system), earache | Cloves | Milled, pulp is semeared inside the ears | ||

| Food (condiment) | Bulb (clove) | Raw or boiled, added to mutiple foods | ||

| Religious rites | Complete bulb | Dried, several bulbs braided and hung at the entrance of houses to ward off bad vibes | ||

| Allium sp., N, EE25467 | Cebollín | Medicinal (auditive system) | Bulb | Raw, milled, pulp smeared inside the ears |

| Lilium candidum L., E, EE25466 | Lirio | Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| LOMARIOPSIDACEAE | ||||

| Nephrolepis exaltata (L.) Schott, N, EE25465 | Helecho | Ornamental, by its beautiful perennial foliage | Whole plant | Planted in pots in private gardens |

| LHYTRACEAE | ||||

| Heimia salicifolia (Kunth) Link, N, EE25169 | Jarilla | Medicinal (dermic system), dermatitis | Leaves | Milled, boiled in water, use as cataplam |

| Lagerstroemia indica L., E, EE25244 | Crespón | Ornamental, by its beautiful perennial foliage and showy flowers | Whole plant | Planted in pots in public and private gardens |

| Punica granatum L., E, EE25154 | Granada | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), diarrhea | Peels | Boiled in water, drink the solution | ||

| Food | Fruit | Raw | ||

| MAGNOLIACEAE | ||||

| Magnolia grandiflora L., N, EE25171 | Magnolia | Ornamental, by its perennial foliage and beautiful white flowers | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| MALVACEAE | ||||

| Alcea rosea L., E, EE25357 | Malva rosa | Ornamental, by its big and beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Hibiscus denudatus Benth., N, EE25174 | Hibisco | Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Hibiscus syriacus L., E, EE25417 | Malva | Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Malva parviflora L., N, EE25418 | Malva de patio | Medicinal (circulatory system), varicose veins | Fruit and leaves | Boiled, drink the solution and chew and swallow the ground fruits and leaves |

| Tilia mexicana Schltdl., N, EE25419 | Tila | Medicinal (nervous system), insomnia | Dried flowers | Boiled in water, drink the solution |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens by its majestic bearing | ||

| Sida rhombifolia L., N, EE25420 | Hierba del cochino | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system) diarrhea | Immature fruit | Boiled in water, drink the infusion |

| MELIACEAE | ||||

| Azadirachta indica A.Juss., E, EEEE25265 | Neem (Nim) | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), stomach pain, cramps, constipation | Bark | Boiled in water, drink solution |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Melia azedarach L., E, EE25266 | Canelo | Medicinal (dermic system), wound, skin irritation | Bark and leaves | Boiled, infusion used as cataplasm in the wounded area |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| MORACEAE | ||||

| Ficus carica L., E, EE25268 | Higo | Food | Fruit | Raw or boiled and canned fruit |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Fruit and leaves | Raw, leaves boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Morus celtidifolia Kunth, N, EE25349 | Mora | Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Fruit | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Food | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Dye | Fruit | Raw, squeezed | ||

| MORINGACEAE | ||||

| Moringa oleifera Lam., E, EE25351 | Moringa | Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| MUSSACEAE | ||||

| Mussa x oleifera Lam., E, EE25415 | Plátano | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| MYRTACEAE | ||||

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh., E, EE25416 | Eucalipto | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), nasal congestion | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Medicinal (nervous system), stress | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Psidium guajava L., N, EE25228 | Guayaba | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), fever | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), diarrhea | Fruit | Raw, eat several fruits | ||

| Food | Fruit | Raw and canned fruits | ||

| Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L. M. Perry, E, EE25350 | Clavo | Food (condiment) | Floral buds (immature and dry) | Raw or bolied, used in multiple ways |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), constipation | Fruit | Boiled, drink the infusion or chewed | ||

| NYCTAGINACEAE | ||||

| Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd., N, EE25223 | Bugambilia | Ornamental, by its showy flowers | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Medicinal (respiratory system) | Bracts and flowers | Boiled in water, drink the solution | ||

| Mirabilis jalapa L., N, EE25252 | Maravilla | Ornamental, by its showy and beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| OLEACEAE | ||||

| Fraxinus americana L., N, EE25255b | Fresno | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Construction | Wood | Dried to make columns and beams of houses | ||

| Fraxinus cuspidata Torr., N, EE25255 | Fresno | Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Fraxinus greggi A. Gray, N, EE25255c | Barretilla | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Construction | Wood | Piles and columns for houses | ||

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Jasminum floridum Bunge, E, EE25372 | Jazmín | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Jasminum officinale L., E, EE25372b | Jazmin | |||

| Ligustrum japonicum Thunb., E, EE25162 | Trueno | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| ONAGRACEAE | ||||

| Oenothera rosea L’Hér. ex Aiton, N, EE25413 | Hierba del golpe | Medicinal (dermic system), external wounds | Whole plant | Raw, milled, smeared in the wounded area |

| PAPAVERACEAE | ||||

| Hunnemannia fumariifolia Sweet, N, EE25348 | Amapola de campo | Ornamental, by its showy yellow flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| PINACEAE | ||||

| Pinus cembroides Zucc., N, EE25353 | Piñonero | Food | Seeds | Raw |

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Pinus greggii Engelm. ex Parl., N, EE25354 | Pino | Fuel | Wood | Dried |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl., N, EE25414 | Pino blanco | Fuel | Wood | Dried |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Religious rites | Resin | In prayer altars | ||

| PIPERACEAE | ||||

| Piper nigrum L., E, EE25356 | Pimienta | Food (condiment) | Seeds | Mixed with different meals |

| PLANTAGINACEAE | ||||

| Antirrhinum majus L., E, EE25459 | Perritos | Ornamental, by its beautiful flowers | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Plantago lanceolata L., N, EE25458 | Llantés | Medicinal (endocrine system), cancer | Leaves | Boiled in water, drink the infusion |

| PLUMBAGINACEAE | ||||

| Plumbago pulchella Boiss., E, EE25158 | Júdica | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (dermic system) | Stems and leaves | Boiled, use the solution as catapalsm | ||

| POLYGONACEAE | ||||

| Polygonum punctatum Elliot, N, EE25407 | Chilillo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| POACEAE | ||||

| Arundo donax L., E, EE25408 | Carrizo | Religious rites | Stems | Religious ornaments |

| Construction | Stems | Roofs | ||

| Avena sativa L., E, EE25373 | Avena | Food | Seeds | Raw or boiled |

| Bambusa sp., E, EE25374 | Religious rites | Stems | Religious ornaments | |

| Construction | Stems | Roofs | ||

| Bouteloua curtipendula (Michx.) Torr., N, EE25409 | Banderita | Forage | Whole plants | Raw |

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf, E, EE25410 | Zacate limón | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Medicinal (gastro-intestinal system) | Stems and leaves | Boiled, drink the infusion | ||

| Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench, E, EE25411 | Sorgo | Forage | Whole plants | Raw |

| Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers., E, EE25412 | Zacate Johnson | Forage | Whole plants | Raw |

| Zea mays L., N, EE25347 | Maíz | Food | Fruit (seeds) | Boiled or cooked with mutliple foods |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), parasites | Styles (female flowers) | Boiled in water, drink the solution | ||

| Medicinal (urinary system), kidney problems | Seeds | Milled, boiled, drink the solution | ||

| PORTULACACEAE | ||||

| Portulaca mundula I. M. Johnston, E, 25216 | Verdolaga | Food | Leaves and stems | Raw (previously disinfected with chlorine) or cooked with different foods |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens (pots) | ||

| RANUNCULACEAE | ||||

| Clematis drummondii Torr. & A.Gray, N, EE25405 | Barba de chivo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| RHAMNACEAE | ||||

| Colubrina greggii S.Watson, N | Colubrina | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| ROSACEAE | ||||

| Crataegus mexicana Moc. & Sessé ex DC., N, 25355 | Tejocote | Medicinal (endocrine system), diabetes | Fruit | Raw or boiled, drink the fruit pulp |

| Medicinal (blood system) | Fruit | Raw or boiled, drink the fruit pulp | ||

| Cydonia oblonga Mill., E, EE25346 | Membrillo | Food | Fruit | Raw or boiled to make canned fruits |

| Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl., E, EE25406 | Níspero | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Medicinal (endocrine and blood systems), diabetes and arterial hypertension | Fruit | Raw, liquefied in water | ||

| Malus domestica Borkh., E, EE25343 | Manzana | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Food | Canned fruits | Boiled | ||

| Alcoholic beverages | Fruit | Fermented | ||

| Prunus armeniaca L., E, EE25344 | Chabacano | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Prunus domestica L., E, EE25345 | Ciruelo | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Prunus persica (L.) Batsch, E, EE25150 | Durazno | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Purshia plicata (D.Don) Henr., N, EE25460 | Rosa de castilla | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), diarrhea | Leaves | Boiled, drink the solution |

| Rosa montezumae Humb. & Bonpl. ex Redout & Thory, N, EE25461 | Rosa | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| RUTACEAE | ||||

| Casimiroa pringlei (S. Wats.) Engl., N, EE25342 | Manguito | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Food | Fruit | Raw | ||

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck, E, EE25404 | Limón | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough, chest pain, throat pain | Leaves and fruit juice | Boiled, drink the solution | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck, E, EE25341 | Naranja | Food | Fruit | Raw |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough, chest pain, throat pain | Leaves and fruit peel and fruit juice | Boiled, drink the solution | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Helietta parvifolia (A. Gray) Benth., N, EE25215 | Barreta | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Construction | Wood | Dried, piles and columns for houses, fences (very durable wood) | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Ruta graveolens L., E, EE25221 | Ruda | Medicinal (respiratory system), cold | Leaves and stems | Boiled |

| Zanthoxylum fagara (L.) Sarg., N, EE25247 | Colima | Construction | Wood | Dried, piles and columns for houses |

| Forage | Leaves | Raw | ||

| Medicinal (respiratory system), asthma | Leaves | Boiled, drink the solution | ||

| Medicinal (skeletal-muscular system), arthritis | Leaves | Boiled, drink the solution | ||

| SALICACEAE | ||||

| Populus mexicana Wesm. Ex DC., N, EE25248 | Álamo, chopo | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Salix nigra Marshall, N, EE25462 | Sauce | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens |

| Fuel | Wood | Dried | ||

| SAPINDACEAE | ||||

| Koelreuteria paniculata Laxm., E, EE25238 | Alfombrilla | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| SCROPHULARIACEAE | ||||

| Leucophyllum frutescens (Berland.) I. M. Johnst., N, EE25161 | Cenizo | Medicinal (endocrine system), hepatitis | Whole plant | Cut into pieces, boiled, drink and take a bath with the solution |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Religious rites | Branches and leaves | Part of the floral bouquets used in prayers and pilgrimages | ||

| SOLANACEAE | ||||

| Capsicum annum var. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill, N, EE25217 | Chile piquín, chile quipín | Food (condiment) | Fruit | Raw |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough, phlegm | Fruit (milled) | Liquefied in water, drink (very spicy drink) | ||

| Capsicum annum var. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill, N, EE25217b | Chile japonés | Food (condiment) | Fruit | Raw |

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in public and private gardens | ||

| Capsicum annum var. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill, N, EE25217c | Chile morrón | Food (condiment) | Fruit | Raw |

| Capsicum annum var. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill, N, EE25217d | Chile jalapeño | Food (condiment) | Fruit | Raw |

| Capsicum annum var. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill, N, EE25217e | Chile serrano | Food (condiment) | Fruit | Raw |

| Medicinal (respiratory system), cough, phlegm | Fruit (milled) | Liquefied in water, drink (very spicy drink) | ||

| Datura stramonium L., N, EE25339 | Toloache | Falling in love | Leaves and seeds | Leaves (boiled in water, drink the solution), seeds (raw, chew and swallow) |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill., E, EE25403 | Tomate | Food | Fruit | Raw or cooked with other foods |

| Medicinal (skeletal-muscular system), muscular pain | Fruit | Raw, pulp, use as cataplasm | ||

| Physalis philadelphica Lam., N, EE25260 | Tomate de fresadilla | Food | Fruit | Mixed with other foods, broths, sauces and stews |

| Solanum ovigerum Dunal, E, EE25463 | Huevitos | Ornamental, by its fruits (egg-like) | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Solanum tuberosum L., E, EE25464 | Papa | Food | Root | Mixed with other foods, broths, sauces and stews |

| TURNERACEAE | ||||

| Turnera diffusa Willd. ex Schult., N, EE25340 | Damiana, hierba del venado | Medicinal (genitourinary system) | Leaves, stems and inflorescences | Boiled in water, drink the solution |

| Forage | Whole plant | Raw | ||

| URTICACEAE | ||||

| Urtica dioica L., N, EE25402 | Hiedra | Medicinal (blood system), purify the blood | Whole plant | Boiled in water, drink the solution |

| VERBENCEAE | ||||

| Lippia graveloens Kunth, N, EE25400 | Orégano | Food (condiment) | Leaves | Dried, added to different foods, broths and stews |

| Verbena canescens Kunth, N, EE25401 | Verbena | Medicinal (nervous system), insomnia | Leaves and stems | Boiled in water, drink solution and bathe with the solution |

| VITACEAE | ||||

| Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch., N, EE25160 | Viña virgen | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Vitis berlandieri Planch., N, EE25338 | Parra, vid | Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens |

| Food | Fruit | Raw | ||

| XANTHORRHOEACEAE | ||||

| Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f., E, EE25250 | Sábila | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), gastritis | Leaves | Pulp, milled, liquefied, drink the solution |

| Medicinal (dermic system), hair restauration; dermical wounds | Leaves | Pulp, smeared pulp all over hair; raw, smeared milled pulp in wounded area | ||

| Ornamental | Whole plant | Planted in private gardens | ||

| ZYGOPHYLLACEAE | ||||

| Larrea tridentata (Sessé & Moc. ex DC.) Coville, N, EE25399 | Gobernadora | Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), spasms | Leaves | Boiled in water, drink the solution |

| Medicinal (dermic system), bad smell | Leaves | Boiled in water, wash bad smelling parts of body | ||

| Smelly feet | Leaves | Dried, put leaves inside shoes | ||

| Cleaning the interior of car radiators | Leaves | Boiled in water, drained hot solution into radiator | ||

| ZINGIBERACEAE | ||||

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe, E, EE25398 | Jengibre | Food (condiment) | Root | Raw, cut into the pieces |

| Medicinal (gastrointestinal system), intestinal inflammation, fever | Root | Raw, liquefied, drink the solution | ||

| Medicinal (dermic system), external wounds | Root | Raw, milled, smeared in wounded areas |

References

- Singh, B.; Singh, B.; Kishor, A.; Singh, S.; Bhat, M.N.; Surmal, O.; Musarella, C.M. Exploring Plant-Based Ethnomedicine and Quantitative Ethnopharmacology: Medicinal Plants Utilized by the Population of Jasrota Hill in Western Himalaya. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.N.; Singh, B.; Surmal, O.; Singh, B.; Shivgotra, V.; Musarella, C.M. Ethnobotany of the Himalayas: Safeguarding Medical Practices and Traditional Uses of Kashmir Regions. Biology 2021, 10, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanum, H.; Ishtiaq, M.; Bhatti, K.H.; Hussain, I.; Azeem, M.; Mehwish, M.; Hussain, T.; Mushtaq, W.; Thind, S.; Bashir, R.; et al. Ethnobotanical and conservation studies of tree flora of Shiwalik mountainous range of District Bhimber Azad and Kashmir, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jernigan, K.A.; Belichenko, O.S.; Kolosova, V.B.; Orr, D.J. Naukan ethnobotany in post-Soviet times: Lost edibles and new medicinals. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Turpin, G.; Ens, E.; Venkataya, B.; Community Mbabaram; Rangers, Y.; Hunter, J. Building partnerships for linking biomedical science with traditional knowledge of customary medicines: A case study with two Australian Indigenous communities. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molares, S.; Ladio, A. Ethnobotanical review of the Mapuche medicinal flora: Use patterns on a regional scale. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 122, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.L.; Tamashiro, J.; Begossi, A. Ethnobotany of Riverine Populations from the Rio Negro, Amazonia (Brazil). J. Ethnobiol. 2007, 27, 46–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Ávila, A. La diversidad lingüística y el conocimiento etnobiológico. In Capital Natural de México, Conocimiento Actual de la Biodiversidad, 1st ed.; CONABIO, Ed.; CONABIO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008; pp. 497–556. [Google Scholar]

- Lira, R.; Casas, A.; Blancas, J. Ethnobotany of Mexico, Interactions of People and Plants in Mesoamérica, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez-Elizondo, R.E.; González-Elizondo, M.; Castro-Castro, A.; González-Elizondo, M.S.; Tena-Flores, J.A.; Chairez-Hernández, I. Comparison of traditional knowledge about edible plants among young Southern Tepehuans of Durango, Mexico. Bot. Sci. 2021, 99, 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonta, M.; Pulido-Silva, M.T.; Diego-Vargas, T.; Vite-Reyes, A.; Vovides, A.P.; Cibrián-Jaramillo, A. Ethnobotany of Mexican and northern Central American cycads (Zamiaceae). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamombe-Manduna, I.; Vibrans, H.; Vázquez-García, V. Género y conocimientos etnobotánicos en México y Zimbabwe, un estudio comparativo. Sociedades rurales. Prod. Y Medio Ambiente 2009, 9, 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Castillón, E.; Villarreal-Quintanilla, J..; Encina-Domínguez, J.A.; Jurado-Ybarra, E.; Cuéllar-Rodríguez, L.G.; Garza-Zambrano, P.; Arévalo-Sierra, J.R.; Cantú-Ayala, C.M.; Himmelsbach, W.; Salinas-Rodríguez, M.M.; et al. Ethnobotanical biocultural diversity by rural communities in the Cuatrociénegas Valley, Coahuila; Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salick, J.; Fang, Z.; Byg, A. Eastern Himalayan alpine plant ecology, Tibetan ethnobotany, and climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, F.; Afza, R.; Mustafa, G. Ethnobotany and sustainable utilization of plants in the Potohar Plateau, Pakistan. In Biodi-Versity, Conservation and Sustainability in Asia Prospects and Challenges in South and Middle Asia, 1st ed.; Öztürk, M., Mulk-Khan, S., Altay, V., Efe, R., Egamberdieva, D., Khassanov, F.O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 911–929. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Traditional ecological knowlegde in perspective. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Concepts and Cases, 2nd ed.; International Programo n Traditional Ecological Knowledge/International Development Research Centre/Canadian Museum of Nature: Otario, Canada, 1993; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pierotti, R.; Wildcat, D. Traditional ecological knowledge: The thrid alternative (comentary). Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, N.; Abbott, L.K.; Negrete-Yankelevich, S.; Andrés, P. Farmes´ knowledge and use of soil fauna in agriculture: A worldwide review. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 3, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Hunn, E. The Utilitarian Factor in Folk Biological Classification. Am. Anthropol. 1982, 84, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunn, E. A Zapotec natural history. In Tree, Herbs and Flowers, Birds, Beasts, and Bungs in the Life of San Juan Gbëë, 1st ed; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nabhan, G.P.; Daugherty, E.; Hartung, T. Health Benefits of the Diverse Volatile Oils in Native Plants of Ancient Ironwood-Giant Cactus Forests of the Sonoran Desert: An Adaptation to Climate Change? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI). Catálogo de las lenguas indígenas nacionales: Variantes lingüísticas de México con sus autodenominaciones y referencias geoestadísticas. In Primera Sección; Diario Oficial de la Federación México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rzedowski, J. Vegetación de México, 1st ed.; Editorial Limusa: CDMX, Mexico, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, E.; Soto, B.; Garza, M.; Villarreal, J.A.; Jiménez, J.; Pando, M.; Sánchez-Salas, J.; Scott-Morales, L.; Cotera-Correa, L. Medicinal plants in the southern region of the State of Nuevo León, México. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Castillón, E.; Villarreal-Quintanilla, J.A.; Rodríguez-Salinas, M.M.; Encinas-Domínguez, A.; González-Rodríguez, H.; Romero-Figueroa, G.; Arévalo, J.R. Ethnobotanical Survey of Useful Species in Bustamante, Nuevo León, Mexico. Hum. Ecol. 2017, 46, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, E.; Villarreal, J.A.; Cantú, C.; Cabral, I.; Scott, L.; Yen, C. Ethnobotany in the Cumbres de Monterrey National Park, Nuevo León, México. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Castillón, E.; Garza-López, M.; Villarreal-Quintanilla, J.Á.; Salinas-Rodríguez, M.M.; Soto-Mata, B.E.; González-Rodríguez, H.; González-Uribe, D.U.; Cantú-Silva, I.; Carrillo-Parra, A.; Cantú-Ayala, C. Ethnobotany in Rayones, Nuevo León, México. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceuterick, M.; Vandebroek, I.; Torry, B.; Pieroni, A. Cross-cultural adaptation in urban ethnobotany: The Colombian folk pharmacopoeia in London. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 120, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandebroek, I.; Balick, M.J. Globalization and Loss of Plant Knowledge: Challenging the Paradigm. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Aziz, M.; Ullah, Z.; Pieroni, A. Wild Food Plant Gathering among Kalasha, Yidgha, Nuristani and Khowar Speakers in Chitral, NW Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrino, E.V.; Wagensommer, R.P. Crop Wild Relatives (CWRs) Threatened and Endemic to Italy: Urgent Actions for Protection and Use. Biology 2022, 11, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, C.R. Ethnobotany and the Loss of Traditional Knowledge in the 21st Century. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Avilez, W.; de Medeiros, P.M.; Albuquerque, U.P. Effect of Gender on the Knowledge of Medicinal Plants: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 6592363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrone, J.J. Hacia una síntesis biogeográfica de México. Rev. Mex. Biodiv. 2005, 76, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrone, J.J. Mexican biogeographic provinces: Map and shapefiles. Zootaxa 2017, 4277, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Síntesis Geográfica de Nuevo León; Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto: Nuevo León, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- González-Medrano, F. Las Comunidades Vegetales de México, 2nd ed.; Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Natura-les/Instituto Nacional de Ecología: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, E.; Arévalo, J.R.; Villarreal, J.A.; Salinas-Rodríguez, M.M.; Encina-Domínguez, J.A.; González-Rodríguez, H.; Cantú-Ayala, C.M. Classification and ordination of main plant communities along an altitudinal gradient in the arid and temperate climates of northeastern Mexico. Sci. Nat. 2015, 102, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Quintanilla, J.A.; Estrada-Castillón, E. Flora de Nuevo León. In Listados Florísticos de México XXIV, 1st ed.; Univer-sidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thiers, B. Index Herbariorum: A Global Directory of Public Herbaria and Associated Staff. New York Botanical Garden´s Virtual Herbarium. 2022. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Martin, G.J. Ethnobotany, 1st ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE). ISE Code of Ethics. 2006. Available online: http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Cunha, L.; Lucena, R.; Alves, R.R.N. Methods and Techniques in Ethnobiology and Ethnoecology, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J.H. Bioststistical Analysis, 1st ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T. Paleontological Data Análisis, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Blackwell, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.A.; Albuquerque, U.P. Técnicas para análise de dados etnobotânicos. In Métodos e Técnicas na Pesquisa Etnobotanica, 1st ed.; Albuquerque, P., Paiva de Lucena, R.F., Cunha, L.V., Eds.; NUPEEA: Pernambuco, Brazil, 2004; pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.; Zohara, Y.; Amotz, D.; Palewitch, D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, M.A. An ethnobotany of Baja California´s Kumeyaay Indians. 2012. Available online: https://digitallibrary.sdsu.edu/islandora/object/sdsu%3A3815 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Farfán, B.; Casas, A.; Ibarra-Manríquez, G.; Pérez-Negrón, E. Mazahua Ethnobotany and Subsistence in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2007, 61, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Flores, M.; Lira, R.; Dávila, P. Estudio etnobotánico de Zapotitlán Salinas, Puebla. Acta Bot. Mex. 2007, 79, 13–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X. Assessment of Aesthetic Quality of Urban Landscapes by Integrating Objective and Subjective Factors: A Case Study for Riparian Landscapes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazos-Chavero, E.; Álvarez-Buylla, M.A. Ethnobotany in a tropical-humid region: The home gardens of Balzpaote, Veracruz, Mexico. J. Ethnob. 1988, 8, 45–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rendón-Correa, A.; Fernández-Nava, R. Plantas con potencial uso ornamental del estado de Morelos, México. Polibotánica 2007, 23, 121–165. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Negrón, E.; Dávila, P.; Casas, A. Use of columnar cacti in the Tehuacán Valley, Mexico: Perspectives for sustainable management of non-timber forest products. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Vega, D.E.; Verde-Star, M.J.; Salinas-González, N.; Rosales-Hernández, B.; Estrada-García, I.; Mendez-Aragón, P.; Carranza-Rosales, P.; González-Garza, M.T.; Castro-Garza, J. Antimycobacterial activity of Juglans regia, Juglans mollis, Carya illinoensis and Bocconia frutescens. Phytotherapy Res. 2008, 22, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghogar, A.; Jiraungkoorskul, K.; Jiraungkoorskul, W. Paper Flower, Bougainvillea spectabilis: Update Properties of Traditional Medicinal Plant. J. Nat. REMEDIES 2016, 16, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pío-León, J.F.; Nieto-Garibay, A.; León-de-la Luz, J.L.; Delgado-Vargas, F.D.; Vega-Aviña, R.; Ortega-Rubio, A. Plantas silvestres consumidas como tés recreativos por grupos de rancheros en Baja California Sur, México. Acta Bot. Mex. 2018, 123, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Reimers, E.A.; Fernández-Cusimamani, E.; Lara-Rodríguez, E.A.; Zepeda-del-Valle, J.M.; Polesny, Z.; Pawera, L. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Zacatecas state, Mexico. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2018, 87, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO World Health Organization. “ICD-10 Version:2010” International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/en (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Arsenov, D.; Župunski, M.; Pajević, S.; Nemeš, I.; Simin, N.; Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Watson, M.; Aloliqi, A.A.; Mimica-Dukić, N. Roots of Apium graveolens and Petroselinum crispum—Insight into Phenolic Status against Toxicity Level of Trace Elements. Plants 2021, 10, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supratman, U.; Fujita, T.; Akiyama, K.; Hayashi, H.; Murakami, A.; Sakai, H.; Koshimizu, K.; Ohigashi, H. Anti-tumor Promoting Activity of Bufadienolides from Kalanchoe pinnata and K. daigremontiana × butiflora. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Chávez, T.; Ramírez-Apan, M.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Martínez-Vázquez, M. Principles of the bark of Amphipterygium adstringens (Julianaceae) with anti-inflammatory activity. Phytomedicine 2004, 11, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Hernández, M.A.; Flores-Merino, M.V.; Sánchez-Flores, J.E.; Burrola-Aguilar, C.; Zepeda-Gómez, C.; Nieto-Trujillo, A.; Estrada-Zúñiga, M.E. Photoprotective Activity of Buddleja cordata Cell Culture Methanolic Extract on UVB-Irradiated 3T3-Swiss Albino Fibroblasts. Plants 2021, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, J.M.; Sato, P.T.; Howald, W.N.; McLaughlin, J.L. Peyote Alkaloids: Identification in the Mexican Cactus Pelecyphora aselliformis Ehrenberg. Science 1972, 176, 1131–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, H.; Steele, B.; Bryant, J.; Toyang, N.; Ngwa, W. Non-Cannabinoid Metabolites of Cannabis sativa L. with Therapeutic Potential. Plants 2021, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarić, S.; Mitrović, M.; Pavlović, P. Review of Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Study of Thymus serpyllum L. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wet, H.; Nkwanyana, M.; van Vuuren, S. Medicinal plants used for the treatment of diarrhoea in northern Maputaland, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Tlahque, J.; Aguirre-Mancilla, C.L.; López-Palestina, C.; Fernández, R.E.S.; Hernández-Fuentes, A.D.; Torres-Valencia, J.M. Constituents, Antioxidant and Antifungal Properties of Jatropha dioica var. dioica. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19852433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Mahmood, T.; Ali, M.; Saeed, A.; Maalik, A. Pharmacological importance of an ethnobotanical plant: Capsicum annuum L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentini, F.; Venza, F. Wild food plants of popular use in Sicily. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezekwe, M.O.; Omara-Alwala, T.R.; Membrahtu, T. Nutritive characterization of purslane accessions as influenced by planting date. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 1999, 54, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, S.S.; Chung, F.L.; Richie, J.P.; Akerkar, S.A.; Borukhova, A.; Skowronski, L.; Carmella, S.G. Effects of watercress con-sumption on metabolism of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen in smokers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1995, 4, 877–884. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, C.I.R.; Haldar, S.; Boyd, L.A.; Bennett, R.; Whiteford, J.; Butler, M.; Pearson, J.R.; Bradbury, I.; Rowland, I.R. Watercress supplementation in diet reduces lymphocyte DNA damage and alters blood antioxidant status in healthy adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Alonso, M.T.; Bye, R.; López-Mata, L.; Pulido-Salas, M.T.P.; de Tapia, E.M.; Koch, S.D. Etnobotánica de la cultura teotihuacana. Bot. Sci. 2014, 92, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, H.S. Origin of the common bean, Phaseolus vulgaris. Econ. Bot. 1969, 23, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loko, L.E.Y.; Toffa, J.; Adjatin, A.; Akpo, A.J.; Orobiyi, A.; Dansi, A. Folk taxonomy and traditional uses of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) landraces by the sociolinguistic groups in the central region of the Republic of Benin. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouad, H.; Haloui, M.; Rhiouani, H.; El Hilaly, J.; Eddouks, M. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes, cardiac and renal diseases in the North centre region of Morocco (Fez–Boulemane). J. Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2001, 77, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Galván, J.; Reyna-González, M.; Chico-Romero, P.A.; Martínez-Ruiz, N.D.R.; Núñez-Gastélum, J.A.; Monroy-Sosa, A.; Ruiz-May, E.; Fernández, R.G. Seed Characteristics and Nutritional Composition of Pine Nut from Five Populations of P. cembroides from the States of Hidalgo and Chihuahua, Mexico. Molecules 2019, 24, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, J.A.; Ulibarri, E.A.; Puentes, J.P.; Costantino, F.B.; Arenas, P.M.; Pochettino, M.L. Leguminosas medicinales y ali-menticias utilizadas en la conurbación Buenos Aires-La Plata, Argentina. Bol. Lat. Car. Plantas Med. Arom. 2011, 10, 443–455. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, R.W.; Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Sikharulidze, S.; Kikvidze, Z.; Kikodze, D.; Tchelidze, D.; Khutsishvili, M.; Batsatsashvili, K.; Hart, R.E. A comparative ethnobotany of Khevsureti, Samtskhe-Javakheti, Tusheti, Svaneti, and Racha-Lechkhumi, Republic of Georgia (Sakartvelo), Caucasus. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; De, S.; Belkheir, A. Avena sativa (Oat), A Potential Neutraceutical and Therapeutic Agent: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Bonnländer, B.; Lang, S.C.; Pischel, I.; Forster, J.; Khan, J.; Jackson, P.A.; Wightman, E.L. Acute and Chronic Effects of Green Oat (Avena sativa) Extract on Cognitive Function and Mood during a Laboratory Stressor in Healthy Adults: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study in Healthy Humans. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M. Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. In Yam bean Pachyrhizus DC, 1st ed.; International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva, A.; Carrascosa, C.; Ramos, F.; Raheem, D.; Raposo, A. Agave Syrup: Chemical Analysis and Nutritional Profile, Applications in the Food Industry and Health Impacts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camou-Guerrero, A.; Reyes-Garcia, V.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Casas, A. Knowledge and Use Value of Plant Species in a Rarámuri Community: A Gender Perspective for Conservation. Hum. Ecol. 2007, 36, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, A.; López-García, S.; Basurto-Peña, F. Content of Nutrient and Antinutrient in Edible Flowers of Wild Plants in Mexico. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2007, 62, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, R.F.; Trujillo, S. Ethnobotany of Ferocactus histrix and Echinocactus platyacanthus (Cactaceae) in the Semiarid Central Mexico: Past, Present and Future. Econ. Bot. 1991, 45, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M.P. The origins of an important cactus crop, Opuntia ficus-indica (Cactaceae): New molecular evidence. Am. J. Bot. 2004, 91, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglese, P.; Basile, F.; Schirra, M. Cactus pear fruit production. In Cacti: Biology and Uses, 1st ed.; Nobel, P., Ed.; University of California/Berkeley: California, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, R.; Caballero, J. Ethnobotany of the Wild Mexican Cucurbitaceae. Econ. Bot. 2002, 56, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, B.E.; Gressel, J. Dealing with the Evolution and Spread of Sorghum Halepense Glyphosate Resistance in Argentina, 1st ed.; Consultancy Report to SENASA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dejene, T.; Agamy, M.S.; Agúndez, D.; Martín-Pinto, P. Ethnobotanical Survey of Wild Edible Fruit Tree Species in Lowland Areas of Ethiopia. Forests 2020, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants of Slovakia. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, S.; Fresnedo, J.; Mathuriau, C.; López, J.; Andrés, J.; Muratalla, A. The edible fruit species in Mexico. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1767–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargıoğlu, M.; Cenkci, S.; Serteser, A.; Konuk, M.; Vural, G. Traditional Uses of Wild Plants in the Middle Aegean Region of Turkey. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre, L.; Cummins, I.; Logan-Hines, E. Agave americana and Furcraea andina: Key Species to Andean Cultures in Ecuador. Bot. Sci. 2018, 96, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin-Hart, K.; Cox, P.A. A cladistic approach to comparative ethnobotany: Dye plants of the southwestern United States. J. Ethnobiol. 2000, 2082, 303–325. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, A.; Caballero, J.; Valiente-Baunet, A. Use, management and domestication of columnar cacti in South Central Mexico: A historical perspective. J. Ethnobiol. 1999, 19, 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo-Urbina, C.J.; Álvarez-Ríos, G.D.; Zárraga, L.C. Edible flowers commercialized in local markets of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, Mexico. Bot. Sci. 2021, 100, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, C.C.; Williams, M.; Brennan, A.; Woeste, K.; Jacobs, J.; Hoban, S.; Moore, M.; Romero-Severson, J. Save Our Species: A Blueprint for Restoring Butternut (Juglans cinerea) across Eastern North America. J. For. 2020, 119, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes-de-Araújo, F.; de-Paulo, F.D.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Underutilized plants of the Cactaceae family: Nutritional aspects and technological applications. Food Chem. 2021, 362, 130196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felger, R.; Joyal, E. The palms (Arecaceae) of Sonora, Mexico. Aliso 1999, 18, e22275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saslis-Lagoudakis, C.H.; Klitgaard, B.B.; Forest, F.; Francis, L.; Savolainen, V.; Williamson, E.M.; Hawkins, J.A. The Use of Phylogeny to Interpret Cross-Cultural Patterns in Plant Use and Guide Medicinal Plant Discovery: An Example from Pterocarpus (Leguminosae). PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, Y.G.; Alcántara, M.R.M.; Zerón, H.M. Eryngium heterophyllum and Amphipterygium adstringens Tea Effect on Triglyceride Levels; A Clinical Trial. Tradit. Integr. Med. 2019, 4, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]