Assessing the Private Sector’s Efforts in Improving the Supply Chain of Hermetic Bags in East Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, Sampling, and Data

2.2. Marketing Efficiency and Profit Margins

2.3. Analysis of Distribution Channels within the Supply Chain

3. Results

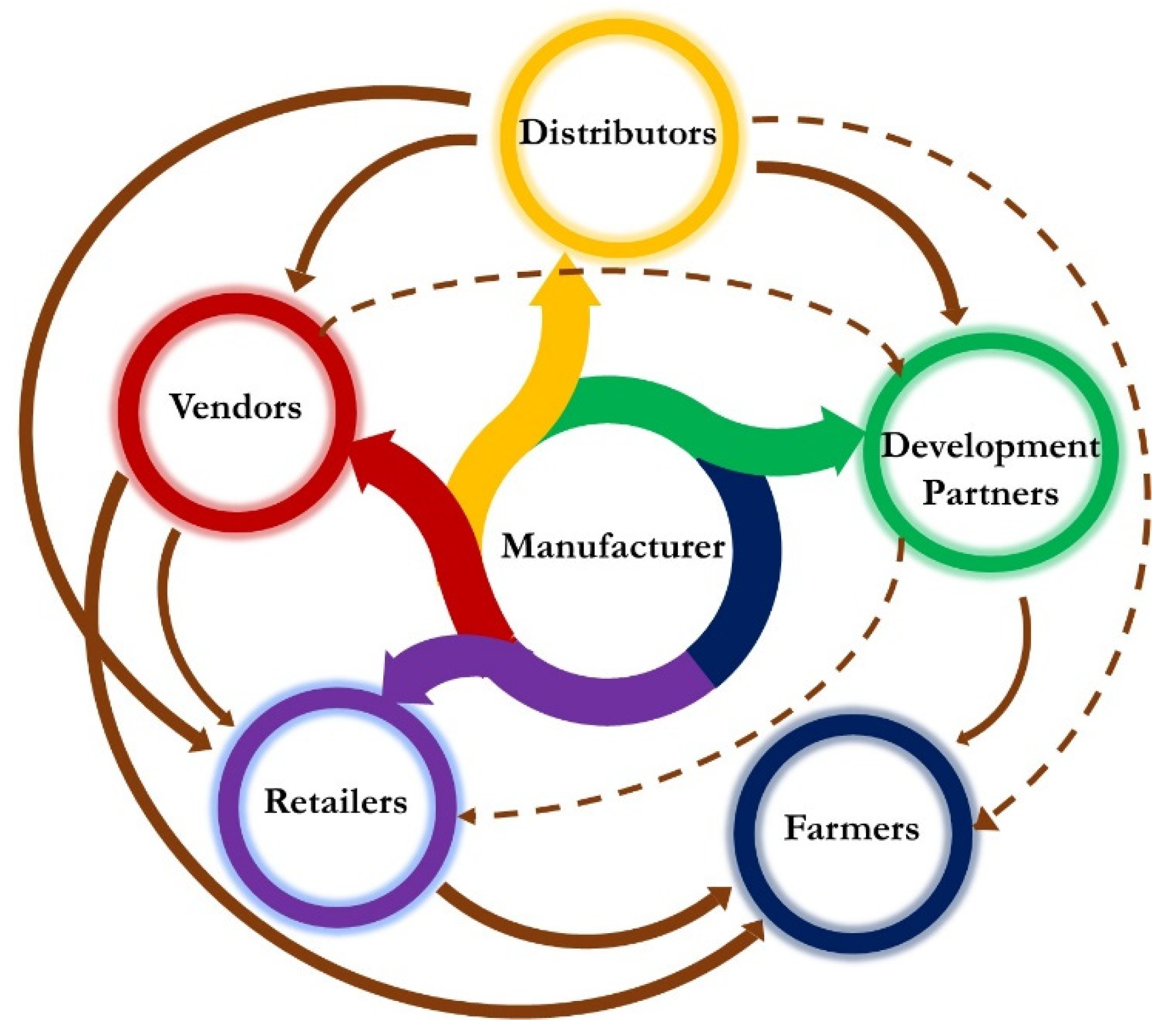

3.1. Existing Distribution Channels and Relationships between Supply Chain Actors

3.2. Characteristics of Supply Chain Actors

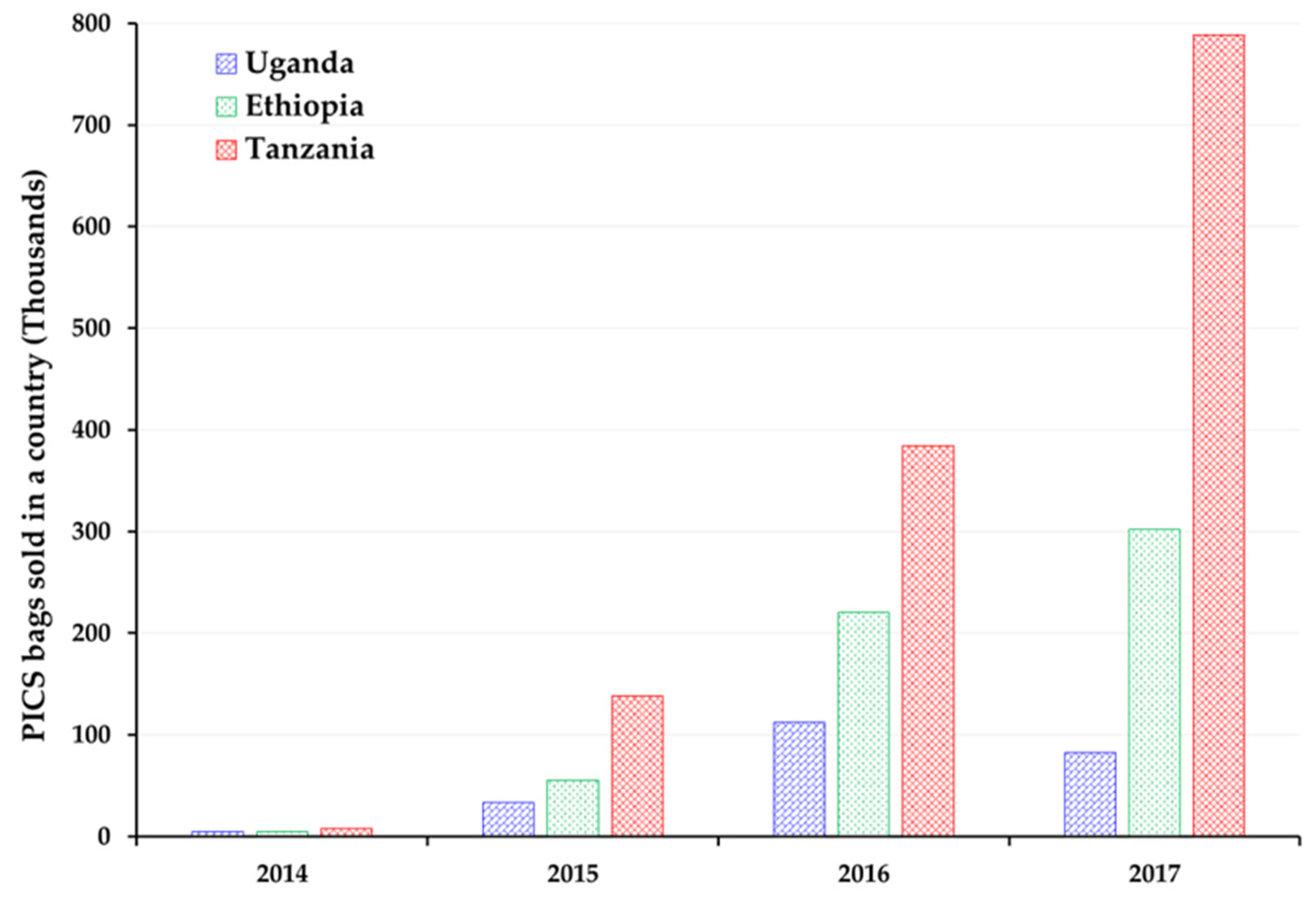

3.2.1. Manufacturers

3.2.2. Distributors

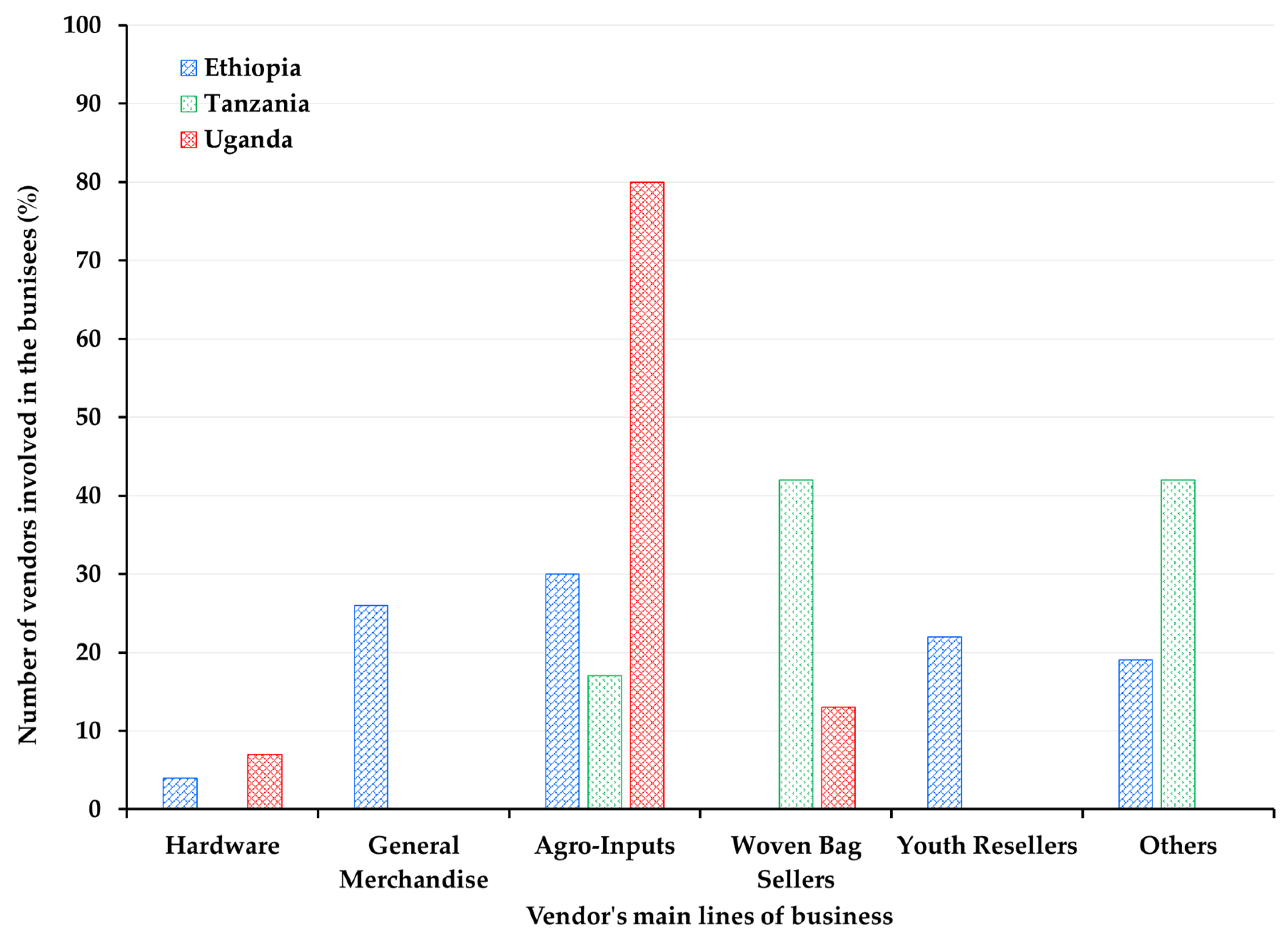

3.2.3. Vendors and Retailers

3.2.4. Farmers

3.3. Marketing Efficiency and Profit Margins

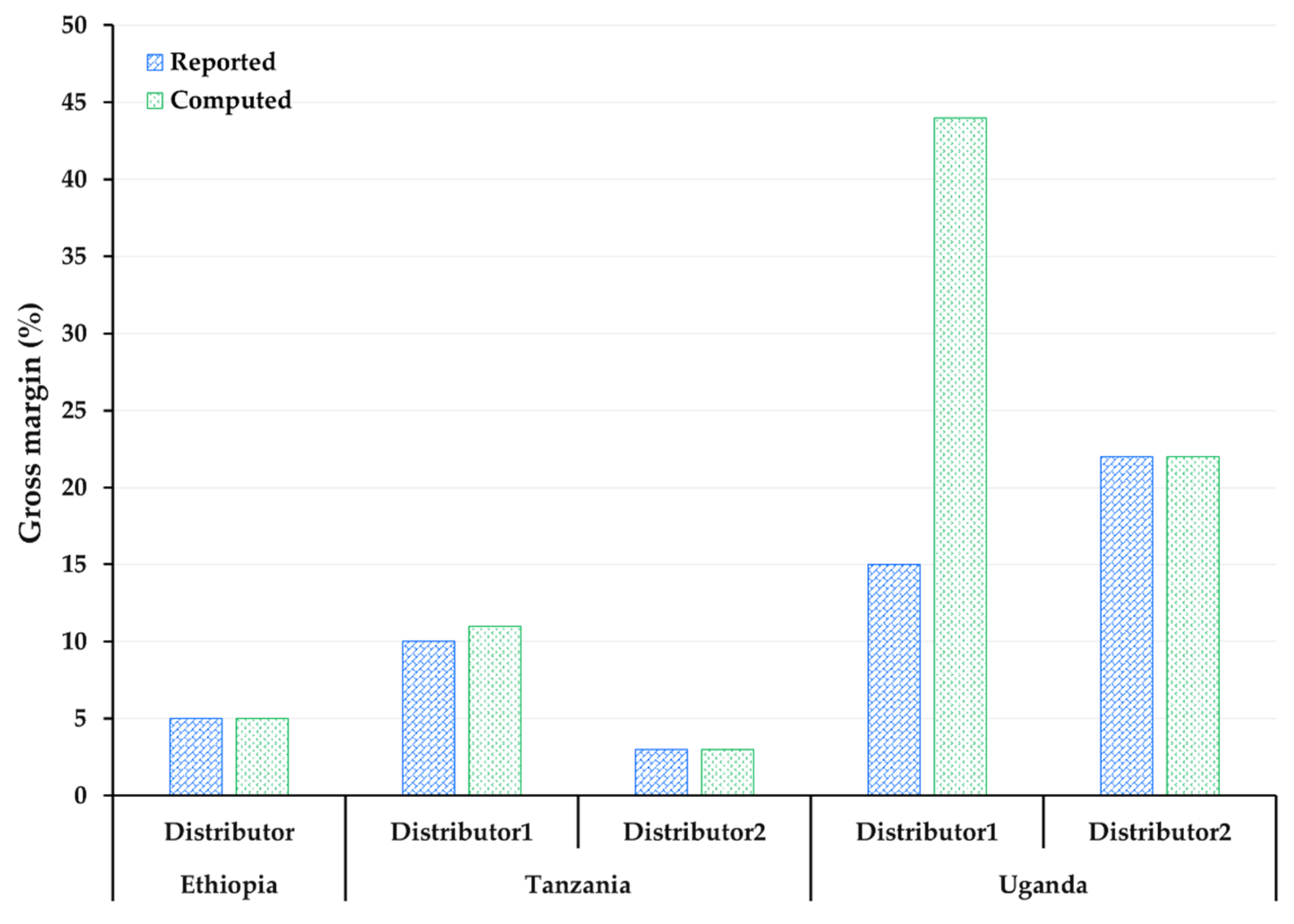

3.3.1. Marketing Efficiency

3.3.2. Profit Margins

3.4. Factors Affecting the Supply and Access to PICS Bags

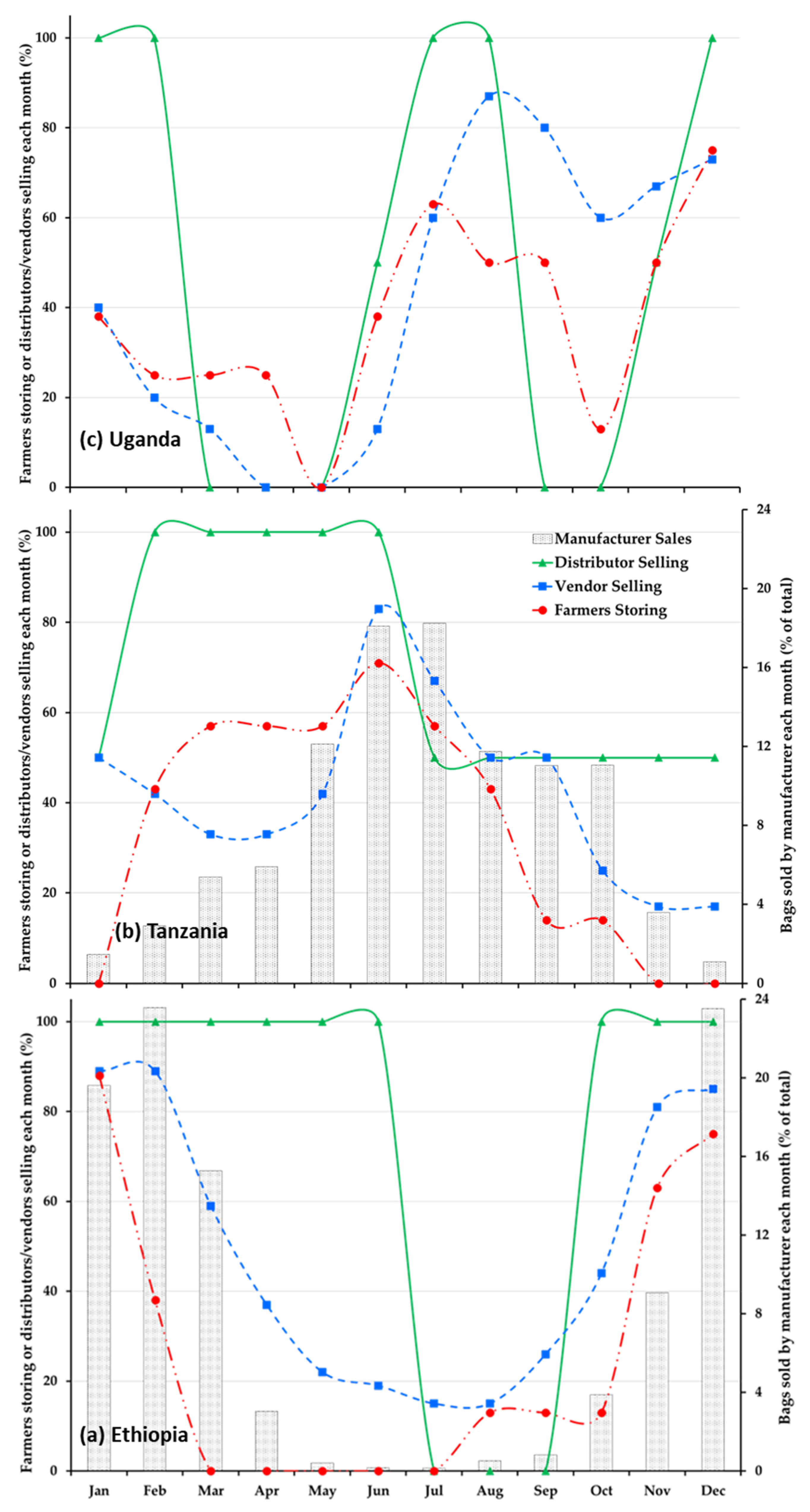

3.4.1. Seasonality

3.4.2. Availability and Timing of Supply of PICS Bags

3.4.3. Logistics—Production and Transportation Costs

3.4.4. Access to Capital

3.4.5. Pricing of PICS Bags to Farmers

4. Discussion

4.1. Distribution of the PICS Bags

4.2. Market Building-Demand Creations

4.3. Marketing Efficiency and Profit Margins

4.4. Factors Affecting the Supply and Access to PICS Bags

4.4.1. Seasonality

4.4.2. Inventory Management and Timing of Supply of PICS Bags

4.4.3. Supply Chain Development Strategy

4.5. Access to Capital

4.6. Pricing of PICS Bags

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santos, C.A.F.; Da Costa, D.C.C.; Da Silva, W.R.; Boiteux, L.S. Genetic analysis of total seed protein content in two cowpea crosses. Crop Sci. 2012, 52, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitonga, Z.M.; De Groote, H.; Kassie, M.; Tefera, T. Impact of metal silos on households’ maize storage, storage losses and food security: An application of a propensity score matching. Food Policy 2013, 43, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larochelle, C.; Alwang, J.R. Impacts of Improved Bean Varieties on Food Security in Rwanda Impacts of Improved Bean Varieties on Food Security in Rwanda. In Proceedings of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, 2014 Annual Meeting, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 27–29 July 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, K.; Wong, M. Evaluating seasonal food storage and credit programs in east Indonesia. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 115, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutiga, S.K.; Mushongi, A.A.; Kangéthe, E.K. Enhancing Food Safety through Adoption of Long-Term Technical Advisory, Financial, and Storage Support Services in Maize Growing Areas of East Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoulaye, T.; Ainembabazi, J.H.; Alexander, C.; Baributsa, D.; Kadjo, D.; Moussa, B.; Omotilewa, O.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Shiferaw, F. Postharvest Loss of Maize and Grain Legumes in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from Household Survey Data in Seven Countries; EC-807-W; Purdue Extension: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Alexander, C.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. A simple methodology for measuring profitability of on-farm storage pest management in developing countries. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2014, 58, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WorldBank. Missing Food: The Case of Postharvest Grain Losses in Sub-Saharan Africa; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski, B.; Hanson, C.; Lomax, J.; Kitinoja, L.; Waite, R.; Searchinger, T. Toward a Sustainable Food System: Reducing Food Loss and Waste; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stathers, T.; Holcroft, D.; Kitinoja, L.; Mvumi, B.M.; English, A.; Omotilewa, O.; Kocher, M.; Ault, J.; Torero, M. A scoping review of interventions for crop postharvest loss reduction in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affognon, H.; Mutungi, C.; Sanginga, P.; Borgemeister, C. Unpacking Postharvest Losses in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Meta-Analysis. World Dev. 2015, 66, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, H.; Kimenju, S.C.; Likhayo, P.; Kanampiu, F.; Tefera, T.; Hellin, J. Effectiveness of hermetic systems in controlling maize storage pests in Kenya. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2013, 53, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndewga, M.K. Effectiveness and economics of hermetic bags for maize storage: Results of a randomized controlled trial in Kenya. Crop Prot. 2016, 90, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Njoroge, A.W.; Affognon, H.D.; Mutungi, C.M.; Manono, J.; Lamuka, P.O.; Murdock, L.L. Triple bag hermetic storage delivers a lethal punch to Prostephanus truncatus (Horn) (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) in stored maize. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2014, 58, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.B.S.B.; Baributsa, D.; Woloshuk, C. Assessing Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) bags to mitigate fungal growth and aflatoxin contamination. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2014, 59, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, L.L.; Margam, V.; Baoua, I.; Balfe, S.; Shade, R.E. Death by desiccation: Effects of hermetic storage on cowpea bruchids. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2012, 49, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baributsa, D.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Murdock, L.; Moussa, B. Profitable chemical-free cowpea storage technology for smallholder farmers in Africa: Opportunities and challenges. Gates Open Res. 2019, 3, 853. [Google Scholar]

- Baributsa, D.; Njoroge, A.W. The use and profitability of hermetic technologies for grain storage among smallholder farmers in eastern Kenya. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2020, 87, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainville, D.; Ness-Edelstein, B. AgResults Evaluation: Kenya On-Farm Storage Challenge Project. Sustainability Assessment; Prepared for the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office and the AgResults Steering Committee; Abt Associates: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baributsa, D.; Ignacio, M.C. Developments in the use of hermetic bags for grain storage. In Advances in Postharvest Management of Cereals and Grains; Maier, D.E., Ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78676-352-5. [Google Scholar]

- Govereh, J.; Muchetu, R.G.; Mvumi, B.M.; Chuma, T. Analysis of distribution systems for supply of synthetic grain protectants to maize smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe: Implications for hermetic grain storage bag distribution. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2019, 84, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baributsa, D.; Abdoulaye, T.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Dabiré, C.; Moussa, B.; Coulibaly, O.; Baoua, I. Market building for post-harvest technology through large-scale extension efforts. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2014, 58, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouhoheflin, T.; Coulibaly, J.Y.; D’Alessandro, S.; Aitchédji, C.C.; Damisa, M.; Baributsa, D.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Stephen, D.A.; Aitchédjid, C.C.; Damisae, M.; et al. Management lessons learned in supply chain development: The experience of PICS bags in West and Central Africa. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotilewa, O.J.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Ainembabazi, J.H. Subsidies for Agricultural Technology Adoption: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment with Improved Grain Storage Bags in Uganda. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 101, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabé, M.M.; Baoua, I.B.; Baributsa, D. Adoption and Profitability of the Purdue Improved Crop Storage Technology for Grain Storage in the South-Central Regions of Niger. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, B.; Abdoulaye, T.; Coulibaly, O.; Baributsa, D.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. Adoption of on-farm hermetic storage for cowpea in West and Central Africa in 2012. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2014, 58, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.H.; Wani, M.H.; Zargar, B.A.; Wani, S.A.; Kubrevi, S.S. Pesticide Delivery System in Apple Growing Belt of Kashmir Valley. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2012, 25, 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Shayashone Youth Entrepreneurship in Ethiopia. Available online: https://shayashone.com/eventandstories/youth-entrepreneurship-ethiopia (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- AGRA. Assessment of Fertilizer Distribution Systems and Opportunities for Developing Fertilizer Blends; Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, T.; Kirama, S.L.; Selejio, O. The Supply of Inorganic Fertilizers to Smallholder Farmers in Tanzania; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Rhee, B.-D. Trade credit for supply chain coordination. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 214, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C.S. Social enterprises as supply-chain enablers for the poor. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2011, 45, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianu, J.N.; Mairura, F.; Ekise, I.; Chianu, J.N. Farm input marketing in western Kenya: Challenges and opportunities. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 3, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Baributsa, D.; Djibo, K.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Moussa, B.; Baoua, I. The fate of triple-layer plastic bags used for cowpea storage. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2014, 58, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Region (District) | Survey Period | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-performing | Low-performing | ||

| Ethiopia | Oromia (Jimma, Limu) | Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR; Butajira, Walaita Sodo, Sawla, and Arba Minch) | April, 2018 |

| Tanzania | Southern Highlands (Mbeya, Mbinga, Mwanza) | Dar es Salaam | January, 2018 |

| Uganda | Northern (Lira, Gulu, Aduku) | Eastern (Iganga, Jinja, Lugazi, Bugiri, Mbale) | November, 2017 |

| Country | Manufacturer | Distributor | Vendors | Development Partners/NGOs | Famers Focus Groups | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | 1 | 1 | 27 | 5 | 8 | 42 |

| Tanzania | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 25 |

| Uganda | 0 | 2 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 31 |

| Total | 2 | 5 | 54 | 14 | 23 | 98 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omotilewa, O.J.; Baributsa, D. Assessing the Private Sector’s Efforts in Improving the Supply Chain of Hermetic Bags in East Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12579. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912579

Omotilewa OJ, Baributsa D. Assessing the Private Sector’s Efforts in Improving the Supply Chain of Hermetic Bags in East Africa. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12579. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912579

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmotilewa, Oluwatoba J., and Dieudonne Baributsa. 2022. "Assessing the Private Sector’s Efforts in Improving the Supply Chain of Hermetic Bags in East Africa" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12579. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912579

APA StyleOmotilewa, O. J., & Baributsa, D. (2022). Assessing the Private Sector’s Efforts in Improving the Supply Chain of Hermetic Bags in East Africa. Sustainability, 14(19), 12579. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912579