Analyzing Determinants of Job Satisfaction Based on Two-Factor Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background

2.1. Two-Factor Theory

2.2. Job Satisfaction

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

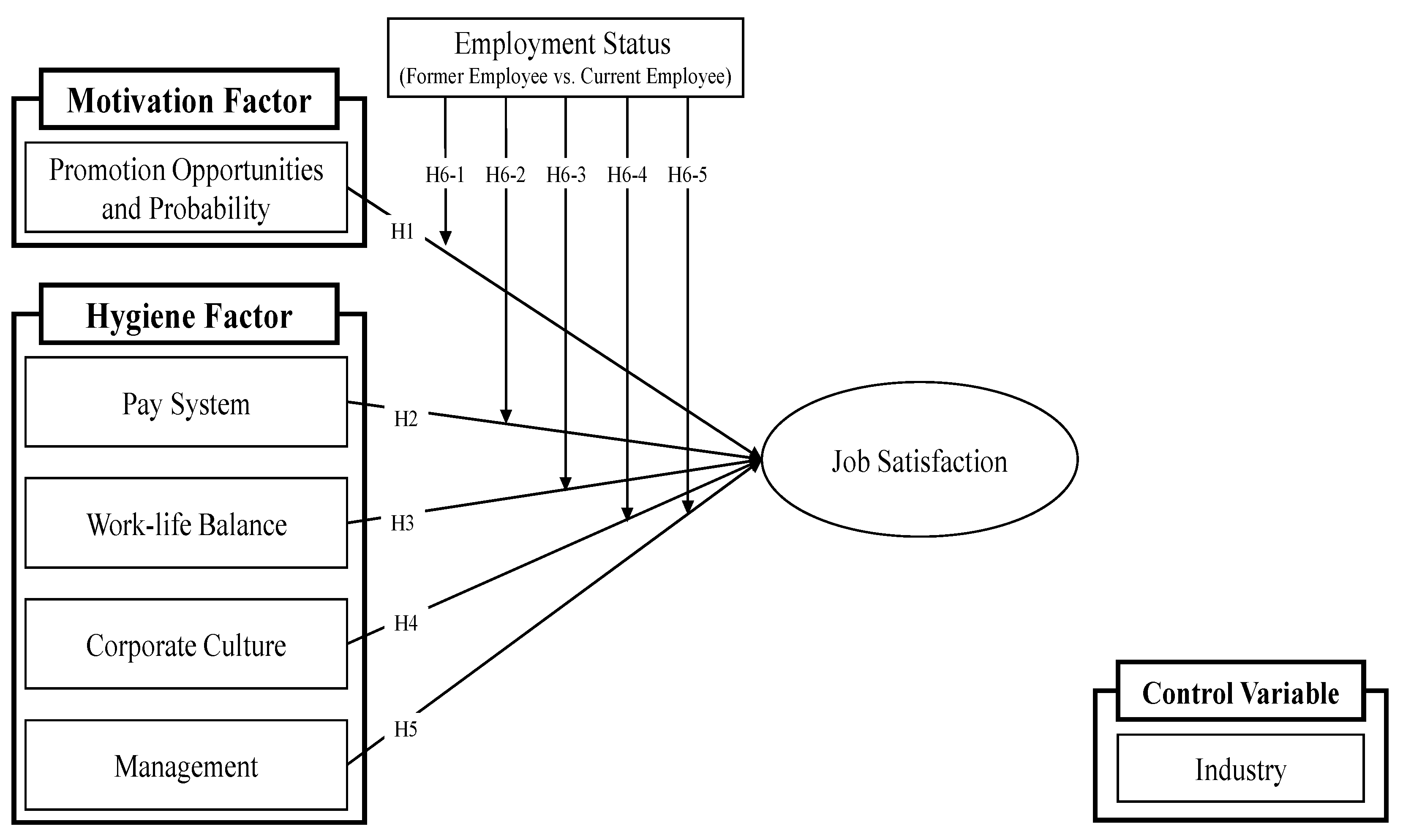

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Research Hypothesis

3.2.1. The Relationship between Promotion Opportunities/Possibilities and Job Satisfaction

3.2.2. The Relationship between a Pay System and Job Satisfaction

3.2.3. The Relationship between Work–Life Balance Factors and Job Satisfaction

3.2.4. The Relationship between Corporate Culture and Job Satisfaction

3.2.5. The Relationship between Management and Job Satisfaction

3.2.6. Moderating Effect of Former or Current Employees

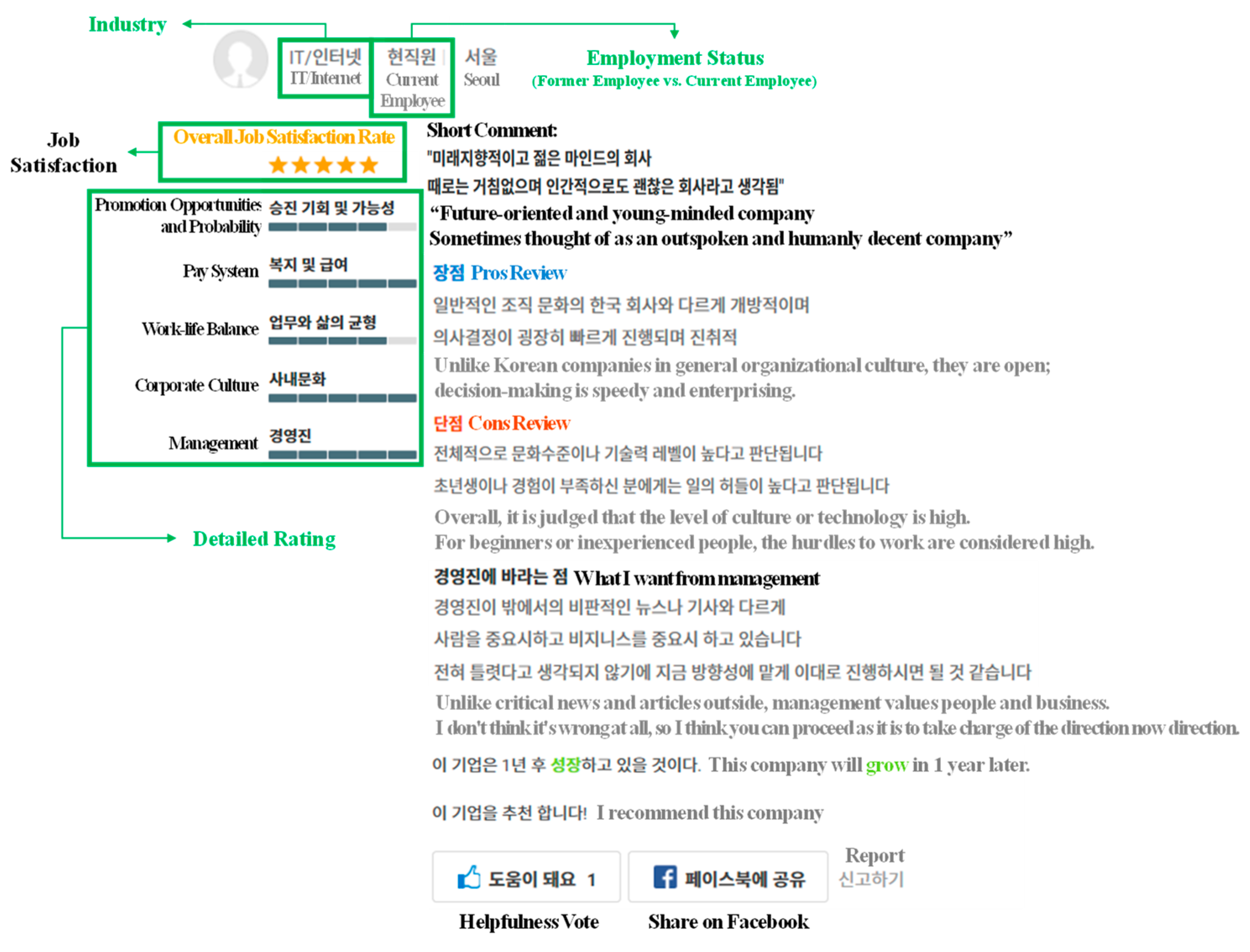

3.3. Dataset

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Analysis over All Industries

4.3. Analysis of an Individual Industry

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

6.2. Academic and Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hannon, E.; Knupfer, S.; Stern, S.; Sumers, B.; Nijssen, J.T. An Integrated Perspective on the Future of Mobility, Part 3: Setting the Direction toward Seamless Mobility; McKinsey Center for Future Mobility: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Stogdill, R.M. Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications, 3rd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-00-2901-500-1. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, S. Strategic human resource practices and product innovation. Organ. Stud. 2008, 29, 821–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, W. The relationship among emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, performance, and intention to leave. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2019, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zamanan, M.; Alkhaldi, M.; Almajroub, A.; Alajmi, A.; Alshammari, J.; Aburumman, O. The influence of HRM practices and employees’ satisfaction on intention to leave. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kilani, M.H. The influence of organizational justice on intention to leave: Examining the mediating role of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. J. Manag. Strategy 2017, 8, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashmoola, B.; Ahmad, F.; Kheng, Y.K. Job satisfaction and intention to leave in SME construction companies of United Arab Emirates (UAE). Bus. Manag. Dyn. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.C.; El’Fred, H.Y. The link between organizational ethics and job satisfaction: A study of managers in Singapore. J Bus Ethics 2001, 29, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, C.C. Work Motivation in Organizational Behavior, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-08-0585-604-0. [Google Scholar]

- Alrawahi, S.; Sellgren, S.F.; Altouby, S.; Alwahaibi, N.; Brommels, M. The application of Herzberg’s two-factor theory of motivation to job satisfaction in clinical laboratories in Omani hospitals. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snydermann, B. The Motivation to Work; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959; ISBN 978-04-7137-389-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, L.Y.S.; Lin, S.W.; Hsu, L.Y. Motivation for online impulse buying: A two-factor theory perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, M.C.; Abrudan, M.M. Adapting Herzberg’s two factor theory to the cultural context of Romania. Proced. Soc. Behav. 2016, 221, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, M.A.; Surya, A.V. Two factor theory of motivation and satisfaction: An empirical verification. Ann. Data Sci. 2016, 3, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaio, T.J. Social desirability and survey. Surv. Subj. Phenom. 1984, 2, 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.R.; Mathur, A. The value of online surveys. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabirian, A.; Kietzmann, J.; Diba, H. A great place to work!? Understanding crowdsourced employer branding. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.C.; Huang, R.; Wen, Q.; Zhou, D. Crowdsourced employer reviews and stock returns. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 134, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, P.; Meschke, F.; Guthrie, J.P. Family firms, employee satisfaction, and corporate performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 34, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, S.; Ramos, R.F.; Rita, P. What drives job satisfaction in IT companies? Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2020, 70, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, R.S. Effect of motivational factors on job satisfaction of administrative staff in telecom sector of Pakistan. J. Econ. Dev. Manag. IT Financ. Mark. 2018, 10, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, F. Level of job satisfaction in Agribusiness sector in Bangladesh: An application of Herzberg two factors motivation theory. Glob. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 9, 31–59. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3875199 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Rahman, M.H.; Fatema, M.R.; Ali, M.H. Impact of motivation and job satisfaction on employee’s performance: An empirical study. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Bhattacharjee, A. A study to measure job satisfaction among academicians using Herzberg’s theory in the context of Northeast India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thant, Z.M.; Chang, Y. Determinants of public employee job satisfaction in Myanmar: Focus on Herzberg’s two factor theory. Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, B. The Impact of Personality on Job Satisfaction: A Study of Bank Employees in the Southeastern US. IUP J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 18, 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Maidani, E.A. Comparative study of Herzberg’s two-factor theory of job satisfaction among public and private sectors. Public Pers. Manag. 1991, 20, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewen, R.B. Some determinants of job satisfaction: A study of the generality of Herzberg’s theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 1964, 48, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Wigdor, L.A. Herzberg’s dual-factor theory of job satisfaction and motivation: A review of the evidence and a criticism. Pers. Psychol. 1967, 20, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.G. The effects of supervisory behavior on the path-goal relationship. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perf. 1970, 5, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitiris, L. Herzberg’s proposals and their applicability to the hotel industry. Hosp. Educ. Res. J. 1988, 12, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, T.; Enz, C.A. Motivating hotel employees: Beyond the carrot and the stick. Cornell Hotel Rest A 1995, 36, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derby-Davis, M.J. Predictors of nursing faculty’s job satisfaction and intent to stay in academe. J. Prof. Nurs. 2014, 30, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad Kotni, V.V.; Karumuri, V. Application of Herzberg Two-Factor Theory Model for Motivating Retail Salesforce. IUP J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 17, 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Hasanein, A.M. Herzberg’s theory of motivation and job satisfaction: Does it work for hotel industry in developing countries? J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 19, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rand McNally College Pub. Co.: Chicage, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1343. ISBN 978-07-6196-488-9. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, L.E. Exploration of the Usefulness of “Important” Work Related Needs as a Tool for Studies in Job Satisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, R.N.; Schermerhorn, J.R.; Hunt, J.G. Managing Organizational Behavior, 5th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 978-04-7157-750-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, W.K. Science and theory in the practice of educational administration: A pragmatic perspective. Educ. Admin. Q. 1996, 32, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Essentials of Organizational Behavior, 14th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-01-3452-385-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dessler, G. Fundamentals of Human Resource Management, 5th ed.; Pearson: Massachusetts, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-01-3474-021-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Oh, I.S.; Stoverink, A.C.; Park, H.H.; Bradley, C.; Barros-Rivera, B.A. Happy to help, happy to change? A meta-analysis of major predictors of affiliative and change-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 132, 103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, A.H.; Saiyed, A.A. Islam, institutions and entrepreneurship: Evidence from Muslim populations across nations. Int. J. Islamic Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.L. The study of organizational effectiveness. Sociol. Q. 1972, 13, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruneberg, M.M. Understanding Job Satisfaction; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-04-7026-610-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, T. Formerly Assistant Medical Officer, Imperial Chemical Industries. Ment. Health Hum. Relat. Ind. 1954, 7, 366–378. [Google Scholar]

- Melián-González, S.; Bulchand-Gidumal, J.; López-Valcárcel, B.G. New evidence of the relationship between employee satisfaction and firm economic performance. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 906–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, L.M.; Judge, T.A. Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration. Univ. Mich. Alliance Soc. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seashore, S.E.; Taber, T.D. Job satisfaction indicators and their correlates. Am. Behav. Sci. 1975, 18, 333–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.C.; Kendall, L.M.; Hulin, C.L. The Measurement of Satisfaction in Work and Retirement: A Strategy for the Study of Attitudes; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, Y. Determinants of job satisfaction of federal government employees. Public Pers Manag. 1997, 26, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; de Almeida, H. Work engagement, social support, and job satisfaction in Portuguese nursing staff: A winning combination. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 36, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J. Spillover of workplace IT satisfaction onto job satisfaction: The roles of job fit and professional fit. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H.N.; John, J.E. Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for teaching math: Relations with teacher and student outcomes. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.G.; West, M.A.; Shackleton, V.J.; Dawson, J.F.; Lawthom, R.; Maitlis, S.; Robinson, D.L.; Wallace, A.M. Validating the organizational climate measure: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Forde, C.; Spencer, D.; Charlwood, A. Changes in HRM and job satisfaction, 1998–2004: Evidence from the Workplace Employment Relations Survey. Hum. Resour. Manag J. 2008, 18, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, A.; Sarpan, S.; Ramlan, R. Influence of promotion and job satisfaction on employee performance. J. Account. Bus. Financ. Res. 2018, 3, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarsch, H.J.; Shearer, B. Piece rates, fixed wages, and incentive effects: Statistical evidence from payroll records. Int. Econ. Rev. 2000, 41, 59–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, M.A.; Ward, M. Improving nurse retention in the National Health Service in England: The impact of job satisfaction on intentions to quit. J. Health Econ. 2001, 20, 677–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergamit, M.R.; Veum, J.R. What is a promotion? ILR Rev. 1999, 52, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, A.; Forth, J.; Stokes, L. Does employees’ subjective well-being affect workplace performance? Hum. Relat. 2017, 70, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Searching for happiness at work. Psychologist 2007, 20, 726. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamam, F.L.; Teng, S.S.; Abdullah, F.Z. Reward management and job satisfaction among frontline employees in hotel industry in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. 2014, 144, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terera, S.R.; Ngirande, H. The impact of rewards on job satisfaction and employee retention. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, B. Shaping the future research agenda for compensation and benefits management: Some thoughts based on a stakeholder inquiry. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Bosma, H.; Peter, R.; Siegrist, J. Job strain, effort-reward imbalance and employee well-being: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamermesh, D.S. The changing distribution of job satisfaction. J. Hum. Resour. 2001, 36, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynes, S.L.; Gerhart, B. Compensation in Organizations: Current Research and Practice; Pfeiffer: Wasnington, WA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-07-8795-274-7. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. Unequal pay, unequal responses? Pay referents and their implications for pay level satisfaction. J. Manag. Studies 2001, 38, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machová, R.; Zsigmond, T.; Zsigmondova, A.; Seben, Z. Employee satisfaction and motivation of retail store employees. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2022, 1, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeyer, C. Work-life initiatives: Greed or benevolence regarding workers’ time? Trends Oraganizational Behav. 2000, 7, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, S.R.; MacDermid, S.M. Multiple roles and the self: A theory of role balance. J. Marriage Fam. 1996, 58, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.H.; Song, B.G. Study on the Effect of Police Officer’s Awareness of Work-Life Balance on Job Satisfaction -Mediation Effects of Intrinsic Motivation-. Korean Police Stud. Rev. 2014, 13, 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Keeton, K.; Fenner, D.E.; Johnson, T.R.; Hayward, R.A. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work–life balance, and burnout. Obs. Gynecol. 2007, 109, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, B.B.; Briggs, T.E.; Huff, J.W.; Wright, J.A.; Neuman, G.A. Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: A meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wanrooy, B.; Bewley, H.; Bryson, A.; Forth, J.; Freeth, S.; Stokes, L.; Wood, S. The 2011 Workplace Employment Relations Study: First Findings; Department for Business, Innovation & Skills: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-08-5605-770-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, N.; Liang, J.; Roberts, J.; Ying, Z.J. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2015, 130, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechty, J.M.; Anderson, E.A. Flexible workplace policies: Lessons from the federal alternative work schedules act. Fam. Relat. 2007, 56, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, T.E.; Kennedy, A.A. Culture: A new look through old lenses. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1983, 19, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallach, E.J. Organizations: The cultural match. Train. Dev. J. 1983, 37, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C.W.; Harrison, G.L.; McKinnon, J.L.; Wu, A. The organizational culture of public accounting firms: Evidence from Taiwanese local and US affiliated firms. Account. Organ. Soc. 2002, 27, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil, K.; Wakefield, D.B.; Cloutier, M.M.; Tennen, H.; Hall, C.B. Organizational culture predicts job satisfaction and perceived clinical effectiveness in pediatric primary care practices. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H. The Central Role of Communication in Developing the Job Satisfaction and Its Impact on Organizational Performance. Speech Commun. 2012, 19, 96–123. [Google Scholar]

- Artz, B.M.; Goodall, A.H.; Oswald, A.J. Boss competence and worker well-being. IlR Rev. 2017, 70, 419–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Gray, D.; McHardy, J.; Taylor, K. Employee trust and workplace performance. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 116, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.S.; Ambrose, M.L. Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. J Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.L.; Frink, D.D. The effects of organizational restructure on employee satisfaction. Group Organ. Manag. 1996, 21, 278–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roethlisberger, F.J.; Dickson, W.J. Management and the Worker, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-02-0350-301-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, W.H.; Griffeth, R.W.; Hand, H.H.; Meglino, B.M. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.J. Good Green Jobs in a Global Economy: Making and Keeping New Industries in the United States; MIT Press: Massachusett, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-02-6201-822-7. [Google Scholar]

- Khapova, S.N.; Arthur, M.B.; Wilderom, C.P.; Svensson, J.S. Professional identity as the key to career change intention. Career Dev. Int. 2007, 12, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.; Parker, A. Employee Turnover. In Mentoring Millennials in an Asian Context; Emerald Publ. Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, S.P.; Martinez, L. The moderating role of career progression on job mobility: A study of work–life conflict. J. Hosp. Tour Res. 2018, 42, 1106–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Brit. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutte, C.G.; Messick, D.M. An integrated model of perceived unfairness in organizations. Soc. Justice Res. 1995, 8, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, R.; Konovsky, M.A. Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneman, R.L.; Greenberger, D.B.; Fox, J.A. Pay increase satisfaction: A reconceptualization of pay raise satisfaction based on changes in work and pay practices. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, E.R.; Rosen, Å. Performance pay and adverse selection. Scand. J. Econ. 2005, 107, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vegchel, N.; De Jonge, J.; Bosma, H.; Schaufeli, W. Reviewing the effort–reward imbalance model: Drawing up the balance of 45 empirical studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.E.; Danish, R.Q.; Munir, Y. The impact of pay and promotion on job satisfaction: Evidence from higher education institutes of Pakistan. Am. J. Econ. 2012, 2, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.O.; Fields, Z. Compensation management and employee job satisfaction: A case of Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 41, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, G.F.; Ash, R.A.; Bretz, R.D. Benefit coverage and employee cost: Critical factors in explaining compensation satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 1988, 41, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E. Job satisfaction in Britain. Brit. J. Ind. Relat. 1996, 34, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwani, S.B.; Wall, M. A direct test of the efficiency wage model using UK micro-data. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 1991, 43, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.I. Can wage increases pay for themselves? Tests with a productive function. Econ. J. 1992, 102, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.S.; Mukerjee, S.; Sestero, A. Work-family benefits: Which ones maximize profits? J. Manag. Issues 2001, 13, 28–44. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604332 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Moen, P.; Kelly, E.L.; Fan, W.; Lee, S.R.; Almeida, D.; Kossek, E.E.; Buxton, O.M. Does a flexibility/support organizational initiative improve high-tech employees’ well-being? Evidence from the work, family, and health network. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2016, 81, 134–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belias, D.; Trivellas, P.; Koustelios, A.; Serdaris, P.; Varsanis, K.; Grigoriou, I. Human resource management, strategic leadership development and the Greek tourism sector. In Tourism, Culture and Heritage in a Smart Economy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, V. Identifying organizational culture and subcultures within Greek public hospitals. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2008, 22, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffar, N.; Obeidat, A. The effect of total quality management practices on employee performance: The moderating role of knowledge sharing. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y. Relationship between organizational culture, leadership behavior and job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Brief, A.P. Feeling good-doing good: A conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M.; Sutton, R.I.; Pelled, L.H. Employee positive emotion and favorable outcomes at the workplace. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Graen, G. Generalizability of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.P.; Gobdel, B.C. The vertical dyad linkage model of leadership: Problems and prospects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perf. 1984, 34, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, C.C.; Herd, A.M.; Steiner, D.D. Attributional conflict between managers and subordinates: An investigation of leader-member exchange effects. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A., Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Admin. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, E.P.; Shaw, K.L.; Stanton, C.T. The value of bosses. J. Labor Econ. 2015, 33, 823–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Wormley, W.M. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. Job characteristics, employee voice and well-being in Britain. Ind. Relat. J. 2008, 39, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiresmaili, M.; Moosazadeh, M. Determining job satisfaction of nurses working in hospitals of Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2013, 18, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Sourdif, J. Predictors of nurses’ intent to stay at work in a university health center. Nurs. Health Sci. 2004, 6, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, T. Why You Shouldn’t Ignore Glassdoor. HR Magazine 2015. Available online: https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/content/features/why-you-shouldn-t-ignore-glassdoor (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Eu, Y.S.; Kim, J.M. Personal characteristics of the food industry employees influence to the organizational commitment: Moderating effect of gender and major. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2012, 15, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Yeying, Y.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, D.C. A Study on Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction of Chinese Bankers and the Moderating Effect of Demographic Characteristics. Manag. Inf. Syst. Rev. 2014, 33, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motivation Factors | Hygiene Factors |

|---|---|

| Achievement | Company Policy & Administration |

| Recognition | Supervision·Technical |

| Work Itself | Interpersonal Relation |

| Responsibility | Working Conditions |

| Advancement | Salary |

| Possibility of Growth | Personal Life |

| Status | |

| Job Security |

| Researchers | Constructs |

|---|---|

| [45] | Job Performance, Company Culture, Job Autonomy and Diversity, etc. |

| [19] | Compensation and Benefits, Manager, Work–life Balance, etc. |

| [46] | Salary, Status, Job Stability, Recognition, Sense of Belonging, etc. |

| [47] | Salary and Welfare, Work–life Balance, Management Leadership, etc. |

| [48] | Work Environment, Work Type, Compensation, etc. |

| [49] | Job Characteristics, Organizational Environment, Age, Gender, Education, etc. |

| [50] | Job Itself, Salary, Promotion, Supervision, Peer Relationships |

| [51] | Salary, Promotion Opportunities, Role Clarity, Peer Relationships |

| [52] | Personal Factors (Ability, Competency, Beliefs), Environmental Factors (Salary, Promotion, Relationship with Boss and Colleagues) |

| [53] | Working Conditions, Job Suitability |

| [54] | Compensation, Welfare, Job Itself, Supervision |

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Industry | Nine industries including IT web communication, construction, education, media design, service, trade/transport, banking and finance, pharmaceutical/medical welfare, and chemical manufacturing |

| Employment Status | Former or Current employee (binary scale) |

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | Overall job satisfaction (5-point scale) |

| Promotion Opportunities and Probability (PO) | Satisfaction with HR system within the organization (5-point scale) |

| Pay System (PS) | Satisfaction with pay system or wages within the organization (5-point scale) |

| Work–life Balance (WB) | Satisfaction with balance of work and life (5-point scale) |

| Corporate Culture (CC) | Satisfaction with the culture established within the organization (5-point scale) |

| Management (MG) | Satisfaction with relationship with management or boss’s treatment (5-point scale) |

| Former Employees | Current Employees | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 224,731 | 130,486 | 355,199 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| JS | 3.17 | 1.030 | 355,199 |

| PO | 2.98 | 1.019 | 355,199 |

| PS | 3.09 | 1.109 | 355,199 |

| WB | 3.03 | 1.226 | 355,199 |

| CC | 3.06 | 1.144 | 355,199 |

| MG | 2.68 | 1.080 | 355,199 |

| JS | PO | PS | WB | CC | MG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS | 1 | |||||

| PO | 0.531 ** | 1 | ||||

| PS | 0.594 ** | 0.456 ** | 1 | |||

| WB | 0.561 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.379 ** | 1 | ||

| CC | 0.626 ** | 0.434 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.558 ** | 1 | |

| MG | 0.626 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.602 ** | 1 |

| Path | B | β | S.E. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ref: IT Web Communication | |||

| Construction→JS | 0.065 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.006 |

| Education→JS | 0.028 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.006 |

| Media Design→JS | 0.043 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.005 |

| Service→JS | 0.013 ** | 0.004 ** | 0.004 |

| Trade/Transport→S | 0.032 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.004 |

| Banking and Finance→JS | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| Pharmaceutical/Medical Welfare→JS | −0.013 ** | −0.003 ** | 0.005 |

| Chemical Manufacturing→JS | 0.034 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.004 |

| PO→JS | 0.165 *** | 0.163 *** | 0.001 |

| PS→JS | 0.237 *** | 0.255 *** | 0.001 |

| WB→JS | 0.171 *** | 0.204 *** | 0.001 |

| CC→JS | 0.196 *** | 0.218 *** | 0.001 |

| MG→JS | 0.186 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.001 |

| SMC | 0.612 | ||

| Former Employees | Current Employees | Path Differences between Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | B | β | S.E. | B | β | S.E. | |

| Ref: IT Web Communication | |||||||

| Construction→JS | 0.055 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.075 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.008 | −1.783 |

| Education→JS | 0.027 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.064 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.01 | −3.143 ** |

| Media Design→JS | 0.055 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.006 | 0.052 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.008 | 0.347 *** |

| Service→JS | 0.034 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 3.148 ** |

| Trade/Transport→JS | 0.045 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.005 | 0.028 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.006 | 2.006 * |

| Banking and Finance→JS | 0.006 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0.004 | 0.007 | −0.732 |

| Pharmaceutical/Medical Welfare→JS | −0.012 *** | −0.003 *** | 0.006 | −0.017 | −0.004 | 0.007 | 0.527 |

| Chemical Manufacturing→JS | 0.049 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 6.39 *** |

| PO→JS | 0.143 *** | 0.141 *** | 0.002 | 0.194 *** | 0.192 *** | 0.002 | −19.138 *** |

| PS→JS | 0.232 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.002 | 0.249 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.002 | −6.799 *** |

| WB→JS | 0.164 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.001 | 0.173 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.002 | −4.054 *** |

| CC→JS | 0.205 *** | 0.226 *** | 0.002 | 0.178 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.002 | 9.813 *** |

| MG→JS | 0.199 *** | 0.206 *** | 0.002 | 0.173 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.002 | 9.604 *** |

| SMC | 0.600 | 0.625 | |||||

| Path | IT Web Communication | Construction | Education | Media Design | Service |

| PO→JS | 0.193 *** | 0.161 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.140 *** | 0.150 *** |

| PS→JS | 0.250 *** | 0.270 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.245 *** | 0.253 *** |

| WB→JS | 0.170 *** | 0.192 *** | 0.219 *** | 0.169 *** | 0.180 *** |

| CC→JS | 0.218 *** | 0.221 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.204 *** |

| MG→JS | 0.206 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.225 *** | 0.230 *** | 0.211 *** |

| SMC | 0.602 | 0.631 | 0.657 | 0.609 | 0.564 |

| Trade/Transport | Banking and Finance | Pharmaceutical/Medical Welfare | Chemical Manufacturing | ||

| PO→JS | 0.158 *** | 0.167 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.169 *** | |

| PS→JS | 0.227 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.263 *** | |

| WB→JS | 0.223 *** | 0.226 *** | 0.189 *** | 0.229 *** | |

| CC→JS | 0.218 *** | 0.223 *** | 0.233 *** | 0.206 *** | |

| MG→JS | 0.201 *** | 0.177 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.168 *** | |

| SMC | 0.582 | 0.619 | 0.612 | 0.628 |

| PO→JS | PS→JS | WB→JS | |||||||

| Path | Former Employee | Current Employee | Coefficient | Former Employee | Current Employee | Coefficient | Former Employee | Current Employee | Coefficient |

| IT Web Communication | 0.177 *** | 0.206 *** | −3.744 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.273 *** | −4.397 *** | 0.164 *** | 0.164 *** | 0.554 |

| Construction | 0.128 *** | 0.195 *** | −4.966 *** | 0.264 *** | 0.284 *** | −1.300 | 0.192 *** | 0.181 *** | 1.497 |

| Education | 0.098 *** | 0.174 *** | −6.225 *** | 0.258 *** | 0.279 *** | −1.320 | 0.228 *** | 0.197 *** | 2.075 * |

| Media Design | 0.119 *** | 0.184 *** | −5.761 *** | 0.253 *** | 0.236 *** | 2.051 * | 0.161 *** | 0.176 *** | −1.071 |

| Service | 0.138 *** | 0.179 *** | −4.654 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.275 *** | −3.423 *** | 0.173 *** | 0.186 *** | −1.098 |

| Trade/Transportation | 0.139 *** | 0.187 *** | −6.203 *** | 0.225 *** | 0.241 *** | −2.466 * | 0.204 *** | 0.241 *** | −2.775 ** |

| Banking and Finance | 0.141 *** | 0.201 *** | −6.720 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.274 *** | −2.188 * | 0.208 *** | 0.239 *** | −3.270 ** |

| Pharmaceutical & Medical Welfare | 0.168 *** | 0.184 *** | −1.225 | 0.255 *** | 0.267 *** | −1.402 | 0.175 *** | 0.202 *** | −2.294 ** |

| Chemical Manufacturing | 0.144 *** | 0.194 *** | −10.170 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.274 *** | −2.785 ** | 0.219 *** | 0.234 *** | −1.398 |

| CC→JS | MG→JS | SMC | |||||||

| Path | Former Employee | Current Employee | Coefficient | Former Employee | Current Employee | Coefficient | Former Employee | Current Employee | |

| IT Web Communication | 0.224 *** | 0.206 *** | 2.977 ** | 0.218 *** | 0.204 *** | 3.981 *** | 0.592 | 0.608 | |

| Construction | 0.223 *** | 0.214 *** | 1.421 | 0.207 *** | 0.175 *** | 3.718 *** | 0.621 | 0.636 | |

| Education | 0.203 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.415 | 0.228 *** | 0.216 *** | 1.567 | 0.637 | 0.676 | |

| Media Design | 0.253 *** | 0.224 *** | 3.163 ** | 0.231 *** | 0.235 *** | 1.439 | 0.601 | 0.616 | |

| Service | 0.204 *** | 0.200 *** | 0.382 | 0.208 *** | 0.190 *** | 1.978 * | 0.553 | 0.597 | |

| Trade/Transportation | 0.224 *** | 0.200 *** | 3.128 ** | 0.212 *** | 0.194 *** | 3.134 ** | 0.574 | 0.593 | |

| Banking and Finance | 0.241 *** | 0.197 *** | 4.697 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.164 *** | 3.929 *** | 0.612 | 0.621 | |

| Pharmaceutical & Medical Welfare | 0.253 *** | 0.201 *** | 5.117 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.404 | 0.596 | 0.618 | |

| Chemical Manufacturing | 0.219 *** | 0.189 *** | 6.052 *** | 0.177 *** | 0.165 *** | 3.403 *** | 0.618 | 0.640 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, B.; Lee, C.; Choi, I.; Kim, J. Analyzing Determinants of Job Satisfaction Based on Two-Factor Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912557

Lee B, Lee C, Choi I, Kim J. Analyzing Determinants of Job Satisfaction Based on Two-Factor Theory. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912557

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Byunghyun, Changjae Lee, Ilyoung Choi, and Jaekyeong Kim. 2022. "Analyzing Determinants of Job Satisfaction Based on Two-Factor Theory" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912557

APA StyleLee, B., Lee, C., Choi, I., & Kim, J. (2022). Analyzing Determinants of Job Satisfaction Based on Two-Factor Theory. Sustainability, 14(19), 12557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912557