Application of Sensory Marketing Techniques at Marengo, a Small Sustainable Men’s Fashion Store in Spain: Based on the Hulten, Broweus and van Dijk Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Frame

2.1. Sensory Marketing

- -

- Olfactory-based marketing. Humans tend to remember around 35% of what they smell [36], and the human nose can identify nearly 10,000 different smells. With a huge capacity to associate certain smells with specific situations, humankind’s olfactory sense is considered one of the most sensitive and emotional of all senses. Neuromarketing studies have revealed that 75% of human emotions are related to various smells; hence the sense of smell is significant in terms of its influence on customers’ emotional state, and, in turn, buying behavior and consumption patterns. In this regard, several studies performed by the Sense of Smell Institute (SOSI), a division of the non-profit Fragrance Foundation, indicate that while humans are only able to remember 50% of the things that they have seen after a lapse of three months, in the case of smells, their recall rate is as much as 65% even after a year has elapsed.

- -

- Sound-based marketing. After sight, the sound is the most used sense and serves to arouse strong feelings capable of influencing the relationship between consumers and brands. Specialized studies have claimed that people only remember 2% of the sounds they hear [36]; not surprisingly, sound-based marketing is invoked on fewer occasions than that involving the other senses. Nevertheless, music is a key element for building the image of a point of sale (POS) and the brand as such in the mind space of consumers, and, by extension, influences their buying habits at the POS. Likewise, using music to create the optimal shopping ambience can help stores achieve their commercial objectives. Some guidelines have also been framed around what kind of sales objective is served by different kinds of music [6]. For instance, slow music helps people relax and, therefore, to shop more sedately, thus helping increase sales. On the other hand, fast music encourages them to act and, therefore, shop more efficiently, though it does not necessarily translate into increased sales. All the same, it helps stores avoid bottlenecks and, furthermore, elevates customer satisfaction levels.

- -

- Tactile (touch-based) marketing. The sense of touch has the potential to enhance a brand’s identity as it involves an additional level of interaction, besides sight, between the customer and the product. According to recent studies, tactile marketing can also be considered to influence the “unconscious perceptions, sensations, and preferences of consumers” [37]. Tactile marketing can be employed in all contexts where consumers meet brands to subtly shape these interactions. Tactile covers the characteristics of the products themselves (e.g., texture, size, materials, etc.) and those of the POS.

- -

- Taste-based marketing. Since the sense of taste is related to emotional states, it can influence how a person understands, interprets, and responds to a brand. Taste is usually one of the main lures of food and catering businesses, ranging from bars and restaurants that serve food with a recognizable flavor to supermarkets that attract potential buyers with food tastings, to even small appliance brands.

2.2. Sustainable Menswear Market in Spain

2.3. Hulten, Broweus and van Dijk Model

3. Materials and Methods

- -

- By way of a summary outline:

- -

- Type of research: quantitative causal type, specifically quasi-experimental.

- -

- Experiment specifications: before-after type, no control group.

- -

- Treatments to be manipulated: store aroma, shop music, shop window, product rotation, POP (point of purchase) material, staff uniform.

- -

- Test units: Marengo Man shop.

- -

- Confidence level: 90%.

- -

- Criterion to be used: conservative (maximum variance) 50%.

- -

- Sample size: 50%.

- -

- Finally, the experiment to be carried out will work with a sample size of 50, resulting in a relative error of 11.63%.

- -

- This experiment was chosen because it is a relatively recently implemented model in physical shops, the results of which have yielded interesting results in terms of profitability, as demonstrated in previous research. The aim was therefore to test, in addition to economic profitability, social profitability and sustainability.

3.1. The Experimentation

- -

- Thursday, 17 January 2019. From 10 to 12 a.m. (compared to the previous Thursday at the same time).

- -

- Friday, 18 January 2019. From 6 to 8 p.m. (compared to the previous Friday at the same time).

- -

- Saturday, 19 January 2019. From 12 a.m. to 2 p.m. (compared to the previous Saturday at the same time).

- -

- Smell. A soothing and energizing atmosphere was created at Marengo using a distinctive air freshener, which was specially developed based on insights derived from an interview with the head of Sandir Olfactory Branding, a specialty provider of corporate fragrances for men.

- -

- Sight. A professional window dresser José Silgado was hired to design a shop window for Marengo to perk up its visual marketing and kindle shoppers’ curiosity. The second prong of this approach was product rotation, wherein the merchandise was rotated at least once every fortnight to position Marengo amongst its target shoppers as a store that strongly believes in the constant renewal of its high-quality stocks.

- -

- Hearing. A playlist was compiled based on a 2015 survey by Fundación Autor-SGAE [67] of the musical tastes of Marengo’s target customers. Songs that made it to the playlist were those with the highest listenership on radio, most frequently requested by radio listeners, and most frequently purchased and downloaded from music streaming sites, e.g., Spotify and iTunes.

- -

- Additionally, it was decided that the volume of the music should not be more than 50 decibels (“average” intensity) while its rhythm should be varied depending on the number of shoppers in the store at any point of time. Intense and rhythmic music was reserved for times with increased foot traffic and rush hours in the store and slower tracks for other occasions.

- -

- Touch. To ensure potential buyers were able to touch and feel the products on sale without much effort, all the shelves at Marengo were lowered below the average shoulder height (1.65 m), leaving only those products catering more to the shopper’s sense of sight at shoulder height. In addition, a display with accessories was placed next to the checkout counter, so customers could browse and touch other products while paying for their purchases. This exercise helped trigger impulse sales requiring low involvement (on the part of the lone shop executive).

- -

- Taste. There was no scope for taste-based sensory marketing since the merchandise under consideration was sustainable men’s clothing.

3.2. The Study Variables: Likert Scale

- Do you like this shop?

- Why?

- How often do you shop here?

- Why?

- Have you previously shopped here?

- Rate your shopping experience here on a scale of 1 to 7 (where 1 is very bad and 7, very good)

- Say whether you intend to shop here in the future on a scale of 1 to 7 (where 1 is very unlikely and 7, is very likely)

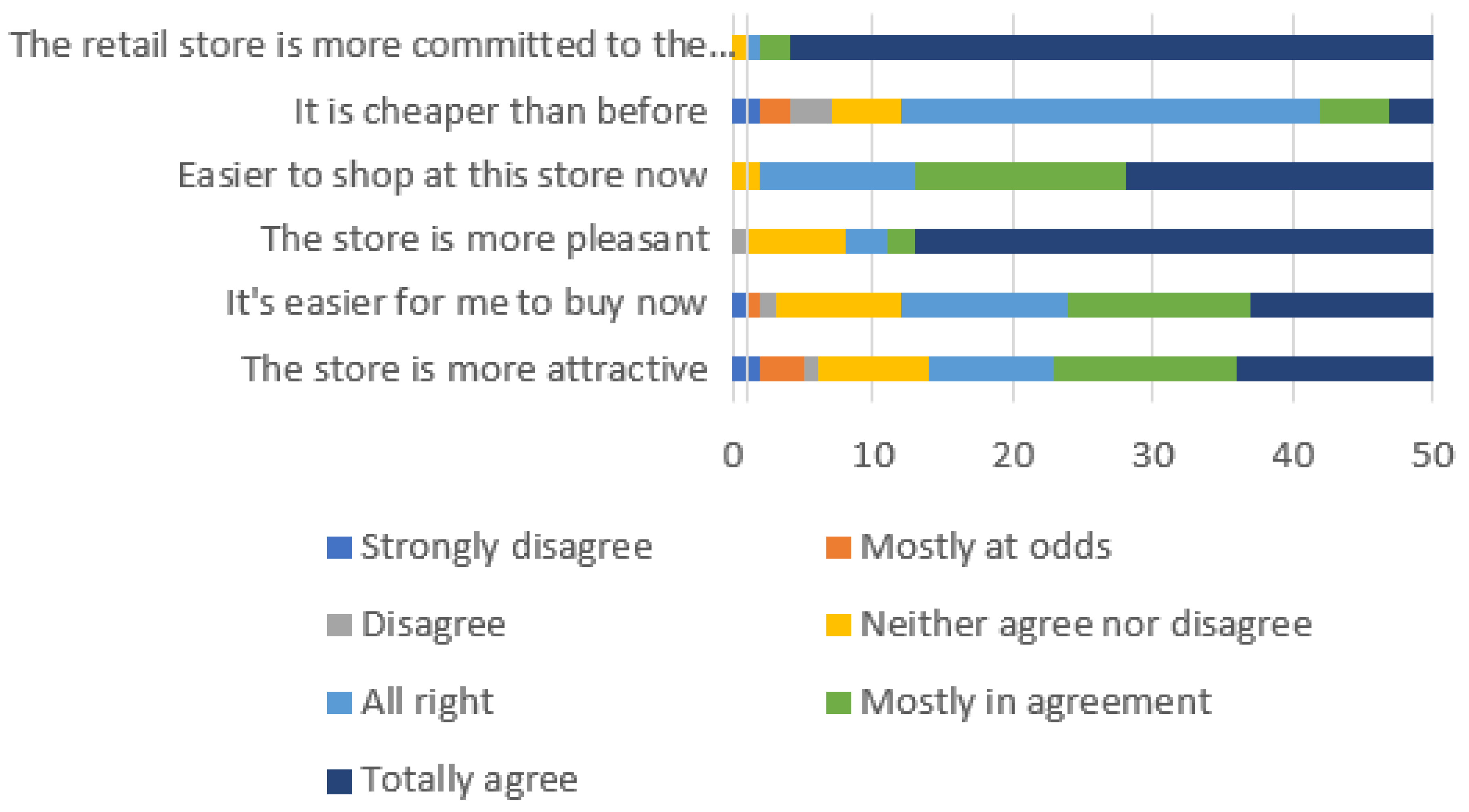

- Strongly disagree

- Mostly at odds

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- All right

- Mostly in agreement

- Totally agree

- The store is more attractive

- It is easier for me to buy now

- The store is more pleasant

- Easier to shop at this store now

- It is cheaper than before

- Is the store more engaged with the environment and development

3.3. The Study Variables: Multiple Regression Model

4. Results

4.1. Economic and profitability Results

4.2. Senses Perception

4.3. Likert Scale

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Consent for Survey

References

- Hassan, S.H.; Yeap, J.A.L.; Al-Kumaim, N.H. Sustainable Fashion Consumption: Advocating Philanthropic and Economic Motives in Clothing Disposal Behaviour. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Balice, A.; Dangelico, R.M. Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability-driven companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Sternthal, B. Ease of message processing as a moderator of repetition effects in advertising. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamacher, K.; Buchkremer, R. Measuring Online Sensory Consumer Experience: Introducing the Online Sensory Marketing Index (OSMI) as a Structural Modeling Approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Marín, G. Merchandising Retail. Comunicación en el Punto de Venta; Advook: Sevilla, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, C.J.R.; Sandoval, L.A. Modelo conceptual para determinar el impacto del merchandising visual en la toma de decisiones de compra de venta. Pensam. Gestión 2014, 36, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro, E.C.D.; Armario, E.M.; Franco, M.J.S. Comunicaciones de Marketing. Planificación y Control; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hulten, B.; Broweus, N.; van Dijk, M. Sensory Marketing; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Marín, G.; Zambrano, R.E. Marketing sensorial: Merchandising a través de las emociones en el punto de venta. Análisis de un caso. AdComunica 2018, 15, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Marín, G.; Zambrano, R.E.; Medina, I.G. El modelo de Hulten, Broweus y Van Dijk de marketing sensorial aplicado al retail español. Caso textil. Mediterr. J. Commun. 2018, 9, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, M. Brand Sense; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abril, C.; Gavilán, D.; Serra, T. Marketing olfatorio: El olor de los deseos. Mark. Ventas 2011, 103, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, O.; Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Digital Sensory Marketing: Integrating New Technologies into Multisensory Online Experience. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Cian, L.; Sokolova, T. The Power of Sensory Marketing in Advertising. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, D.; Abril, C.; Avello, M.; Manzano, R. Marketing Sensorial: Comunicar con los Sentidos en el Punto de Venta; Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Meyers-Levy, J. Distinguishing between the meanings of music: When background music affects product perceptions. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, A.K. The Buying Brain: Secrets for Selling to the Subconscious Mind; John Wiley & Sons: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonadeo, M. ODOTIPO: Historia Natural del Olfato y su Función en la Identidad de Marca; Editorial Universidad Austral: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Japutra, A.; Utami, A.F.; Molinillo, S.; Ekaputra, I.A. Influence of customer application experience and value in use on loyalty toward retailers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing; Deusto: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lick, E. Multimodal Sensory Marketing in retailing: The role of intra-and intermodality transductions. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2022, 25, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobé, M. Branding Emocional. El Nuevo Paradigma para Conectar las Marcas Emocionalmente con las Personas; Divine Egg: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom, M. Compradicción: Verdades y Mentiras Acerca de Por qué las Personas Compran; Grupo Editorial Norma: Bogotá, Colombia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Braidot, N. Neuromarketing: ¿Por Qué tus Clientes se Acuestan con Otro si Dicen que les Gustas tú? Gestión 2000: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fürst, A.; Pečornik, N.; Binder, C. All or Nothing in Sensory Marketing: Must All or Only Some Sensory Attributes Be Congruent with a Product’s Primary Function? J. Retail. 2021, 97, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. Sensory Marketing: Research on the Sensuality of Products; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- del Blanco, R. Á Fusión Perfecta: Neuromarketing; Prentice Hall: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.; García, C. The use of sensorial marketing in stores: Attracting clients through the senses. In Advances in Marketing, Customer Relationship Management, and E-Services; Musso, F., Druica, E., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ortegón, L.O.; Vela, M.R.; Pinzón, Ó.J.R. Comportamiento del consumidor infantil: Recordación y preferencia de atributos sensoriales de marcas y productos para la lonchera en niños de Bogotá. Poliantea 2015, 11, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krishna, A.; Schwarz, N. Sensory marketing, embodiment, and grounded cognition: A review and introduction. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, W.R.A.; Montes, L.S.P.; Vera, G.R. Estímulos auditivos en prácticas de neuromarketing. Caso: Centro Comercial Unicentro. Cuad. Adm. Univ. Val. 2015, 31, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Baruca, A.; Saldivar, R. Is Neuromarketing Ethical? Consumers Say Yes. Consumers Say No. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2014, 17, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, S.; Khare, K. Does Sense Reacts for Marketing-Sensory Marketing. Int. J. Manag. IT Eng. 2015, 5, 2956779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wörfel, P.; Frentz, F.; Tautu, C. Marketing comes to its senses: A bibliometric review and integrated framework of sensory experience in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 704–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, C.; Riviere, J. The concept of Sensory Marketing. Mark. Diss. 2008, 22, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.-W.; Lee, S.-B. Applying Effective Sensory Marketing to Sustainable Coffee Shop Business Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, F.L. Marketing en el Punto de Venta; Thomson Paraninfo: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, C.J.R.; del Río, M.E.S.; García, A.N.; Cataluña, F.J.R.; Méndez, M.B.P. Adaptación de la distribución minorista al consumidor ecológico: El caso de España y Alemania. In Nuevos Horizontes del Marketing y de la Distribución Commercial; Gutiérrez, J.A.T., Casielles, R.V., Alonso, E.E., Mieres, C.G., Eds.; Cátedra Fundación Ramón Areces de Distribución Comercial: Oviedo, Spain, 2018; pp. 355–376. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Marín, G. Shopping as a selling strategy for tourism; combination of marketing mix tools. IROCAMM Int. Rev. Commun. Mark. Mix. 2018, 1, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Zheng, J.H.; Chow, P.S.; Chow, K.Y. Perception of fashion sustainability in online community. J. Text. Inst. 2014, 105, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Lee, H.H. Young Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of sustainability in the apparel industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry Jr, J.F.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fash. Theory 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, K.Y.H. Exploring consumers’ perceptions of eco-conscious apparel acquisition behaviors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 23, 152–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Gam, H. Are fashion-conscious consumers more likely to adopt eco-friendly clothing? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 15, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Treiblmaier, H. How augmented reality impacts retail marketing: A state-of-the-art review from a consumer perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2021, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.C.; Chang, H.H.; Chang, A. Consumer personality and green buying intention: The mediate role of consumer ethical beliefs. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro Mera, A.; Miranda González, F.J.; Rubio Lacoba, S. El estado de la investigación sobre marketing ecológico en España: Análisis de revistas Españolas 1993–2013. Investig. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2016, 12, 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, D.; Foroudi, P.; Jin, Z.; Melewar, T.C. Making sense of sensory brand experience: Constructing an integrative framework for future research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 130–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepp, I.G.; Laitala, K.; Wiedemann, S. Clothing Lifespans: What Should Be Measured and How. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaolaza, U.; Orue, A.; Lizarralde, A.; Oyarbide-Zubillaga, A. Competitive Improvement through Integrated Management of Sales and Operations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xirau, M. El Sector de la Moda en España, En Cifras 2020. Forbes. 15 October 2020. Available online: https://forbes.es/empresas/78279/el-sector-de-la-moda-en-espana-en-cifras/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Zhang, L.; Hale, J. Extending the Lifetime of Clothing through Repair and Repurpose: An Investigation of Barriers and Enablers in UK Citizens. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, J. Millennial Men Increase Sales Revenues for Menswear Apparel by 64%. Linkedin, 20 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, J. La Confianza del Consumidor y las Expectativas se Desploman en Junio. Expansion, 27 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, J.; Woo, H. Investigating male consumers’ lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS) and perception toward slow fashion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakewell, C.; Mitchell, V.W. Generation Y male consumer decision-making styles. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2013, 31, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, S. Inside the mind of Gen Y. Am. Demogr. 2013, 23, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Urh, B. Lifestyle of health and sustainability-the importance of health consciousness impact on LOHAS market growth in ecotourism. Quaestus 2015, 6, 67–177. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion and Sustainability: Design for Change; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, C.; Armstrong, K.; Cano, M.B.; Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Goworek, H.; Ryding, D. Sustainability in Fashion: A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, J.M.; Dunant, C.F.; Lupton, R.C.; Cleaver, C.J.; Serrenho, A.C.H.; Azevedo, J.M.C.; Horton, P.M.; Clare, C.; Low, H.; Horrocks, I.; et al. Absolute Zero. Delivering the UK’s Climate Change Commitment with Incremental Changes to Today’s Technologies; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Binotto, C.; Payne, A. The poetics of waste: Contemporary fashion practice in the context of wastefulness. Fash. Pract. 2017, 9, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, K.M. Waste Management and Sustainable Consumption; Earthscan: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, S.; Lynes, J.; Young, S.B. Fashion interest as a driver for consumer textile waste management: Reuse, recycle or disposal. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidot, N. Cómo Funciona tu Cerebro Para Dummies; Planeta: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Autor-SGAE. Informe SGAE Sobre Hábitos de Consumo Cultural; Sociedad General de Autores y Editores de España: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Osinski, I.C.; Bruno, A.S. Categorías de respuesta en escalas tipo Likert. Psicothema Rev. Anu. Psicol. 1998, 10, 623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Diddi, S.; Yan, R.-N. Consumer Perceptions Related to Clothing Repair and Community Mending Events: A Circular Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Sales | Average Retention | Customer Satisfaction | Intention to Return | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIOR INFORMATION | Thursday, 10 January 2019, from 10 to 12 a.m. | €126.43 | 7 min | 4 | 5 |

| Friday, 11 January 2019, from 6 to 8 p.m. | €136.15 | 7 min | 4 | 5 | |

| Saturday, 12 January 2019, from 12 a.m. to 2 p.m. | €221.59 | 16 min | 5 | 5 | |

| EXPERIMENT | Thursday, 17 January 2019, from 10 to 12 a.m. | €183.25 | 14 min | 6 | 7 |

| Friday, 18 January 2019, from 6 to 8 p.m. | €189.78 | 15 min | 7 | 7 | |

| Saturday, 19 January 2019, from 12 a.m. to 2 p.m. | €250.46 | 19 min | 7 | 7 |

| Visual | Olfactory | Sound | Haptic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior | 27 | 2 | 24 | 5 |

| Post | 43 | 39 | 44 | 15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Marín, G.; Alvarado, M.d.M.R.; González-Oñate, C. Application of Sensory Marketing Techniques at Marengo, a Small Sustainable Men’s Fashion Store in Spain: Based on the Hulten, Broweus and van Dijk Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912547

Jiménez-Marín G, Alvarado MdMR, González-Oñate C. Application of Sensory Marketing Techniques at Marengo, a Small Sustainable Men’s Fashion Store in Spain: Based on the Hulten, Broweus and van Dijk Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912547

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Marín, Gloria, María del Mar Ramírez Alvarado, and Cristina González-Oñate. 2022. "Application of Sensory Marketing Techniques at Marengo, a Small Sustainable Men’s Fashion Store in Spain: Based on the Hulten, Broweus and van Dijk Model" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912547

APA StyleJiménez-Marín, G., Alvarado, M. d. M. R., & González-Oñate, C. (2022). Application of Sensory Marketing Techniques at Marengo, a Small Sustainable Men’s Fashion Store in Spain: Based on the Hulten, Broweus and van Dijk Model. Sustainability, 14(19), 12547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912547