Social, Economic, and Financial Aspects of Modelling Sustainable Growth in the Irresponsible World during COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Voluntarily take into account: economic, legal, social, ethical and ecological aspects in economic activity;

- Take care of the development of its employees, employment growth (also employment of people from groups excluded from the labour market);

- Work towards pro-ecological investments;

- Make a lasting profit whilst creating relations between stakeholders;

- Provide services or/and environmentally friendly products, functioning as a whole;

- Build, modify and implement processes of management and organisation strategies in a company;

- Engage socially but according to the socially accepted ethical standards, sometimes exceeding legal commitments, for the stakeholders’ sake.

- Third-party shareholders;

- Natural environment;

- General social welfare.

2. Available Literature Review

- Philanthropic ones.

- Business ones.

3. Methodology

4. Research Results

5. Discussion

- Service quality index (Wjok). This is a universal index which allows us not only to evaluate insurance companies’ workers’ professionalism both in Sector I and Sector II (their knowledge, skills and experience), but also to evaluate the attitude of every employee toward prosocial factors, their and employee’s respect for them. This index defines the fraction of customers satisfied with the quality of the offered insurance service:where:

- Wjok—customer service quality index.

- JPś—average perceived quality assessment.

- JOmx—maximum expected quality score.

- Another index is the validity of appeals connected with claims settlement (Wzs), which is a combination of information from a survey questionnaire and a dataset connected with the accuracy of the decisions made by the insurance companies’ management when deciding if the incoming complaints connected with claims settlement are valid or not:where:

- Wzs—the validity of the appeals index.

- Sz—valid appeals.

- Swo—the number of appeals in total.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Palminder Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.L.; Marzec, P.E. Social capital, a theory for operations management: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 7081–7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesiński, Z.B. Management in the Region, Poland-Europe-World; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; 344p. [Google Scholar]

- Raszkowski, A. The strategy of local development as the component of creative human capital development process. In Local and Regional Economy in Theory and Practice; Sobczak, E., Bal-Domanska, B., Raszkowski, A., Eds.; Publishing House of Wroclaw University of Economics: Wroclaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, C.I. The Functions of the Executive, 13th ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938; 334p. [Google Scholar]

- Kreps, T.J. Measurement of the social performance of business. In An Investigation of Concentration of Economic Power for the Temporary National Economic Committee (Monograph No. 7); Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1940; 207p. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1953; 150p. [Google Scholar]

- Przybytniowski, J.W. Direct in the provision of insurance services in the area of Eastern Poland. Selected issues. In Dilemmas of Modern Enterprises in the Restructuring Process. Diversification-Integration-Development; Borowiecki, R., Jaki, A., Eds.; Cracow University of Economics: Kraków, Poland; Foundation of the Cracow University of Economics: Cracow, Poland, 2009; pp. 633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Gostomski, E. Social responsibility of banks in the time of financial crisis. In Social Responsibility of Financial Institutions; Bąk, M., Kulawczuk, P., Eds.; Institute for Research on Democracy and Private Enterprise: Warsaw, Poland, 2009; 39p. [Google Scholar]

- Czerwiński, B. The concept of corporate social responsibility in insurance services. Probl. Manag. 2013, 11, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalega, K. Social responsibility of business in the concept of insurance companies. In Market-Society-Culture; Kochanowski University in Kielce: Kielce, Poland, 2018; 7p. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, R.W. Fundamentals of Organization Management, 2nd ed.; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 107–139. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://piu.org.pl/2021 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Yunus, M.; Biggeri, M.; Testi, E. Social Economy and Social Business Supporting Policies for Sustainable Human Development in a Post-COVID-19 World. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresienė, D.; Keliuotytė-Staniulėnienė, G.; Kanapickienė, R. Sustainable Economic Growth Support through Credit Transmission Channel and Financial Stability: In the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Pisani, J.A. Sustainable development—Historical roots of the concept. Environ. Sci. 2006, 3, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDESA. World Economic Situation and Prospects: April 2020 Briefing, No. 136. Available online: www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/world-economic-situation-and-prospects-april2020-briefing-no-136 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Zikic, S. A modern concept of sustainable development. Prog. Econ. Sci. 2018, 5, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdell, C.A. Sustainable Development and Environmental Conservation: Major Regional Issues with Asian Illustrations. Econ. Ecol. Environ. 1996, 5, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The Private Sector and the SDGs: The Need to Move Beyond ‘Business as Usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumi, E.; Yeboah, T.; Kumi, Y.A. Private sector participation in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Ghana: Experiences from the mining and telecommunications sectors. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Green Paper. Promoting a European framework for Corporate Social Responsibility, COM(2001) 366 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; 6p.

- European Commission. Green Paper. Promoting a European framework for Corporate Social Responsibility, COM(2011) 366 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; 7p.

- PN-ISO26000; Guidelines for Corporate Social Responsibility. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012.

- van Zanten, J.A.; van Tulder, R. Multinational enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2018, 1, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoć-Marković, M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Razavi, M. Women in business and leadership: Critiques and discussions. In Proceedings of the Second International Scientific Conference on Employment, Education and Entrepreneurship, Belgrade, Serbia, 16–18 October 2013; pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, E.; Tajpour, M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Demiryurek, K.; Kawamorita, H. Resilience and Knowledge-Based Firms’ Performance: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Thinking. J. Entrep. Bus. Resil. 2021, 4, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Merrow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutu, I.; Agheorghiesei, D.T.; Alecu, I.C. The Online Adapted Transformational Leadership and Workforce Innovation within the Software Development Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybytniowski, J.W. Economic insurance in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Selected Aspects of Business Insurance in Poland and around the World in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic; Przybytniowski, J.W., Grzebieniak, A., Pacholarz, W.M., Eds.; Institute of Economic Research: Olsztyn, Poland, 2021; pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brammer, S.; Branicki, L.; Linnenluecke, M.K. COVID-19, societalization, and the future of business in society. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Knowledge complexity and firm performance: Evidence from the European SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B. Power, leadership and culture as drivers of project management. Am. J. Manag. 2020, 20, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tajpour, M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Braga, V. Investigating social capital, trust and commitment in family business: Case of media firms. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.P.; Tajpour, M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Hosseini, E.; Zolfaghari, M. The impact of entrepreneurial education on technology-based enterprises development: The mediating role of motivation. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus and international business: An entrepreneurial ecosystem perspective. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 62, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Seetharaman, A.; Maddulety, K. Critical success factors influencing the adoption of digitalisation for teaching and learning by business schools. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 3481–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, C.; Ring, P.; Ashby, S.; Wardman, J.K. Resilience in the face of uncertainty: Early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjielias, E.; Christofi, M.; Tarba, S. Contextualizing small business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from small business owner-managers. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Brief #2: Putting the UN Framework for Socio-Economic Response to COVID-19 into Action: Insights. Available online: www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/covid19/Brief2-COVID-19-final-June2020.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- UNDP. COVID-19 and Human Development: Assessing the Crisis, Envisioning the Recovery. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/covid-19_and_human_development_0.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19. Sustainable Development Report 2020; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; 510p. [Google Scholar]

- UNIDO. Coronavirus: The Economic Impact—26 May 2020. Available online: www.unido.org/stories/coronavirus-economic-impact-26-may-2020 (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- UNSDG. Shared Responsibility, Global Solidarity: Responding to the Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/SG-Report-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Covid19.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Seetharaman, M.; Gallucci, J. How Global 500 Companies Are Utilizing Their Resources and Expertise during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://fortune.com/2020/04/13/global-500-companies-coronavirus-response-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Emond, L.; Maese, E. Evolving COVID-19 Responses of World’s Largest Companies. Available online: www.gallup.com/workplace/308210/evolving-covid-responses-world-largest-companies.asp (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Puławska, K. Financial Stability of European Insurance Companies during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clift, K.; Court, A. How are Companies Responding to the Coronavirus Crisis? Available online: www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/how-are-companies-responding-to-the-coronavirus-crisis-d15bed6137 (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- JUST Capital. The COVID-19 Corporate Response Tracker: How America’s Largest Employers Are Treating Stakeholders Amid the Coronavirus Crisis. Available online: https://justcapital.com/reports/the-covid-19-corporate-response-tracker-how-americas-largest-employers-are-treating-stakeholders-amid-the-coronavirus-crisis (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Responsible Business Forum. Available online: www.responsiblebusiness.com (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Przybytniowski, J.W. Responsible business not for everyone. In Management of Restructuring Processes. Concepts-Strategies-Analysis; Borowiecki, R., Jaki, A., Eds.; Cracow University of Economics: Kraków, Poland; Foundation of the Cracow University of Economics: Cracow, Poland, 2012; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Przybytniowski, J.W. Methods of Testing the Quality of Services in the Process of Managing the Property Insurance Market; Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce: Kielce, Poland, 2019; pp. 104–146. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://rf.gov.pl/baza-wiedzy/analizy-i-raporty (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Customer; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Saling, B.M.; Baharuddin, S.; Achmad, G. Effect of Service Quality and Marketing Stimuli on Customer Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Purchasing Decisions. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2016, 4, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Jung, D. The Effect of ESG Activities on Financial Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

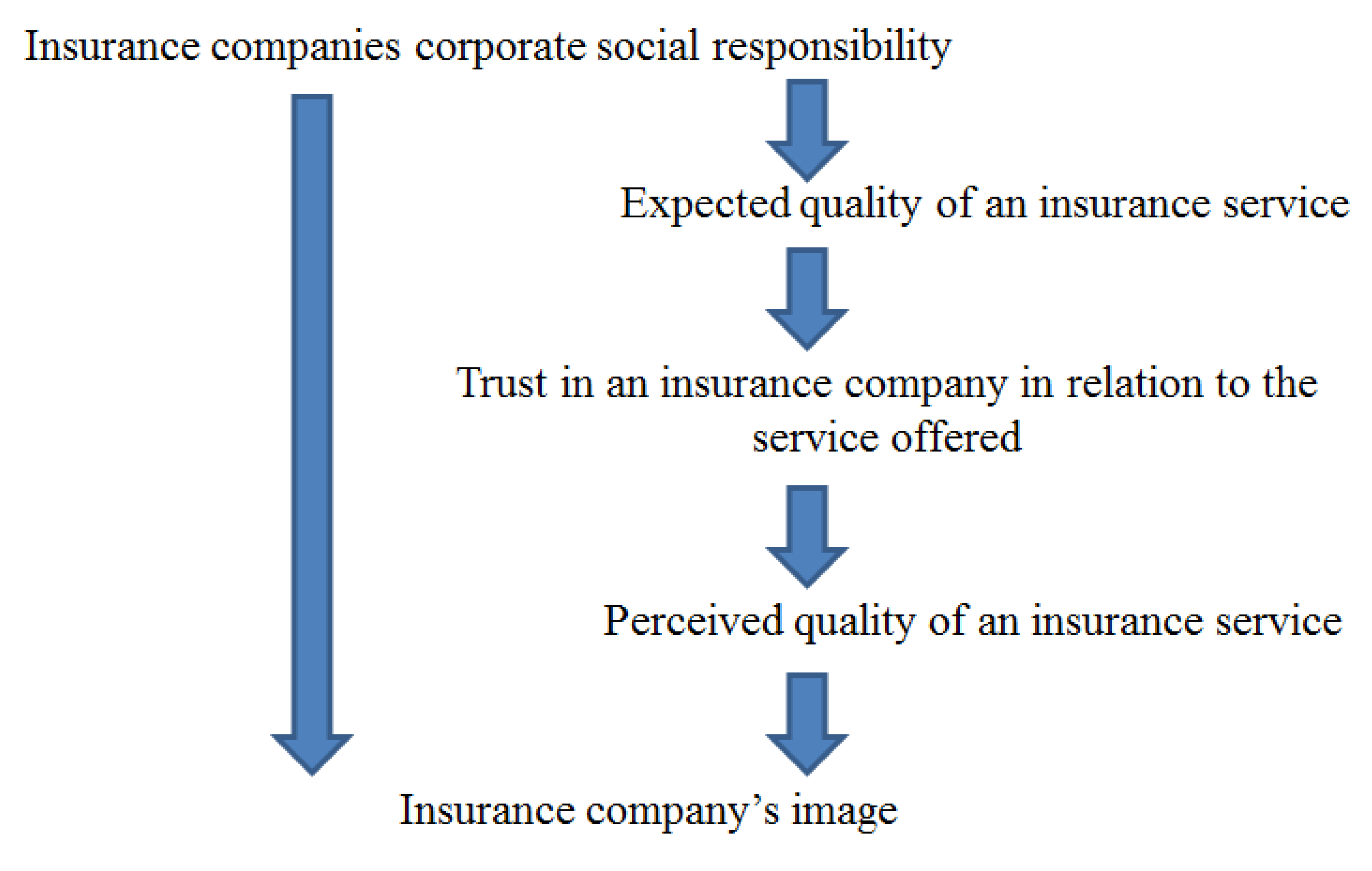

- Poolthong, Y.; Mandhachitara, R. Customer Expectations of CSR, Perceived Service Quality and Brand Effect in Thai Retail Banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2009, 27, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandhachitara, R.; Poolthong, Y. A model of customer loyalty and corporate social respoonsibility. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 7, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.M.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Corporate social responsibility and bank customer Satisfaction: A research agenda. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2008, 29, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlutova, I.; Fomins, A.; Spilbergs, A.; Atstaja, D.; Brizga, J. Opportunities to Increase Financial Well-Being by Investing in Environmental, Social and Governance with Respect to Improving Financial Literacy under COVID-19: The Case of Latvia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SDG/International Institutions | United Nations Industrial Development Organisation [UNIDO] | United Nations Sustainable Development Group [UNSDG] | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [UNDESA] | Sustainable Development Solutions Network [SDSN] and Bertelsmann Stiftung | United Nations Development Programme [UNDP] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of hunger | lack of data | − | lack of data | − | lack of data |

| Quality of Life | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lack of poverty | − | − | − | − | − |

| Quality of education | − | − | − | −/+ | − |

| Innovation | − | lack of data | −/+ | ||

| GDP growth | − | − | − | − | − |

| Sustainable community | lack of data | − | lack of data | −/+ | − |

| Climate improvement | + | −/+ | lack of data | lack of data | lack of data |

| Justice | − | − | −/+ | lack of data | |

| Strong institutions | − | − | −/+ | lack of data | |

| Infrastructure | − | lack of data | lack of data | −/+ | lack of data |

| Fewer inequalities | − | − | − | − | − |

| Clearwater | + | − | lack of data | −/+ | lack of data |

| Appropriate job | − | − | − | − | − |

| Sustainable city | lack of data | − | lack of data | −/+ | − |

| Insurance Companies Sector II | 2010 | 2013 | 2017 | 2020 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Complaints ** | Insurance Company’s Market Share | Structure of the Number of Complaints | Complaints Index | Number of Complaints ** | Insurance company’s Market Share | Structure of the Number of Complaints | Complaints Index | Number of Complaints ** | Insurance Company’s Market Share | Structure of the Number of Complaints | Complaints Index | Number of Complaints ** | Insurance Company’s Market Share | Structure of the Number of Complaints | Complaints Index | |

| Link 4 TU SA. | 530 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 510.0 | 344 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 168.8 | 234 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 152.9 | 330 | 1.2 | 3.7 | 308.3 |

| Generali TU S.A. | 549 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 160.6 | 738 | 2.3 | 5.7 | 247.8 | 509 | 2.0 | 6.1 | 305.0 | 531 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 260.9 |

| TUW TUW | 189 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 150.0 | 95 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 133.3 | 190 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 150.0 | 233 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 260.0 |

| UNIQA TU S.A. | 474 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 121.1 | 665 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 167.7 | 242 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 107.4 | 468 | 2.1 | 5.3 | 252.4 |

| Gothaer TU S.A. * | 403 | 3.9 | 2.1 | 53.8 | 367 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 164.7 | 262 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 193.8 | 183 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 161.5 |

| TU Compensa S.A. VIG | 389 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 108.6 | 226 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 117.1 | 234 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 63.6 | 374 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 123.5 |

| TU Allianz Polska S.A. | 620 | 7.6 | 6.0 | 78.9 | 536 | 6.7 | 4.2 | 62.7 | 424 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 76.1 | 506 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 103.6 |

| PZU S.A. | 2142 | 34.9 | 20.7 | 59.3 | 3013 | 36.6 | 23.4 | 63.9 | 2241 | 36.5 | 26.7 | 73.2 | 2932 | 39.0 | 33.0 | 84.6 |

| STU Ergo Hestia S.A. | 878 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 81.7 | 885 | 11.1 | 6.9 | 62.2 | 781 | 14.4 | 9.3 | 64.6 | 890 | 13.2 | 10.0 | 75.8 |

| TUW Pocztowe | 24 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 200.0 | 34 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 300.0 | 35 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 200.0 | 21 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 66.7 |

| TUiR WARTA S.A. | 1221 | 8.6 | 11.8 | 137.2 | 1469 | 13.9 | 11.4 | 82.0 | 844 | 13.8 | 10.1 | 73.2 | 797 | 15.9 | 9.0 | 56.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przybytniowski, J.W.; Borkowski, S.; Grzebieniak, A.; Garasyim, P.; Dziekański, P.; Ciesielska, A. Social, Economic, and Financial Aspects of Modelling Sustainable Growth in the Irresponsible World during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912480

Przybytniowski JW, Borkowski S, Grzebieniak A, Garasyim P, Dziekański P, Ciesielska A. Social, Economic, and Financial Aspects of Modelling Sustainable Growth in the Irresponsible World during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912480

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzybytniowski, Jarosław Wenancjusz, Stanisław Borkowski, Andrzej Grzebieniak, Petro Garasyim, Paweł Dziekański, and Anna Ciesielska. 2022. "Social, Economic, and Financial Aspects of Modelling Sustainable Growth in the Irresponsible World during COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912480

APA StylePrzybytniowski, J. W., Borkowski, S., Grzebieniak, A., Garasyim, P., Dziekański, P., & Ciesielska, A. (2022). Social, Economic, and Financial Aspects of Modelling Sustainable Growth in the Irresponsible World during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 14(19), 12480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912480