Abstract

Power systems are exposed to various physical threats due to extreme events, technical failures, human errors, and deliberate damage. Physical threats are among the most destructive factors to endanger the power systems security by intelligently targeting power systems components, such as Transmission Lines (TLs), to damage/destroy the facilities or disrupt the power systems operation. The aim of physical attacks in disrupting power systems can be power systems instability, load interruptions, unserved energy costs, repair/displacement costs, and even cascading failures and blackouts. Due to dispersing in large geographical areas, power transmission systems are more exposed to physical threats. Power systems operators, as the system defenders, protect power systems in different stages of a physical attack by minimizing the impacts of such destructive attacks. In this regard, many studies have been conducted in the literature. In this paper, an overview of the previous research studies related to power systems protection against physical attacks is conducted. This paper also outlines the main characteristics, such as physical attack adverse impacts, defending actions, optimization methods, understudied systems, uncertainty considerations, expansion planning, and cascading failures. Furthermore, this paper gives some key findings and recommendations to identify the research gap in the literature.

1. Introduction

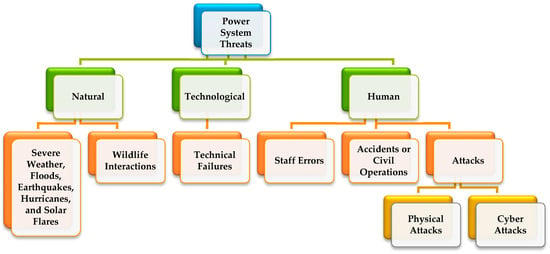

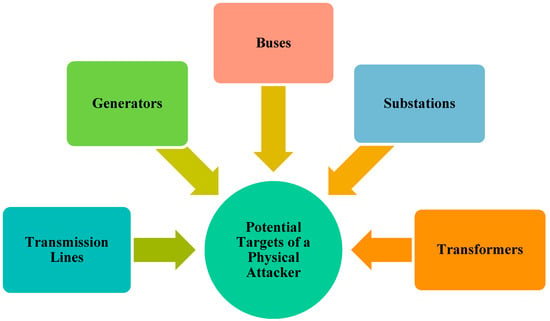

Various natural and unnatural factors may threaten power systems and their normal operation. Such factors have natural, technological, and human origins as presented in Figure 1 [1]. However, physical attacks, as a key threat, intelligently target the most critical components of power grids; they are more destructive than other threatening factors [2,3]. Figure 2 shows the potential targets in a physical attack on power systems. As this figure shows, a physical attack may target every component of the system. Among power systems components, power transmission systems are more endangered due to the dispersion of Transmission Lines (TLs) in wide geographical areas [4]. Disruption agents (physical attackers) can identify the critical TLs and target/destroy them with the aim of load interruption, imposing unserved load cost, disrupting power systems operation (e.g., creating cascading failures), imposing repair/replacement cost of targeted elements, etc.

Figure 1.

The origins of power systems threats.

Figure 2.

The potential targets of physical attacks on power systems.

On the other hand, power systems operators protect power grids by defending actions before the attack and during the restoration process [5]. For instance, installing Distributed Generation (DG) units and incorporating physical attack impacts on transmission expansion planning problems can be considered as a preventive action before the attack [6]. This is while system reconfiguration and redispatch of energy resources to prevent the loss of loads are required actions during the restoration process and until repair/replacement of targeted TLs [7]. Since power systems cannot be fully protected, the system operators estimate the impacts of physical attacks and minimize them [8]. Vulnerability analysis of power systems is an essential step to counter physical attacks. Vulnerability analysis is estimating the ability of a typical power system to follow up on the changes [9,10].

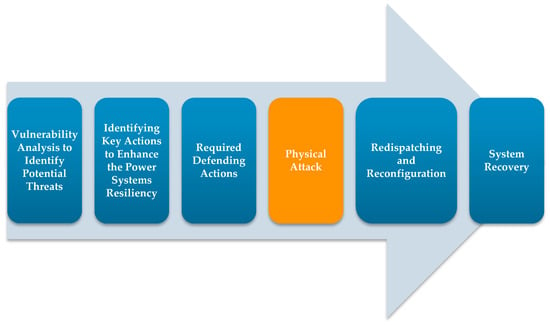

To mitigate physical attacks and conduct proper actions, estimating the characteristics of potential attacks is important [11]. From a viewpoint, the physical attack may be a single attack [12] or multiple attacks [13]. From another perspective, the attacks may be conducted in one action (during a single time interval) [14] or during a multiple time period [15]. The amount of attack resources (budget) is another factor related to the characteristics of a physical attack [16]. Understanding such characteristics can contribute to mitigating the sabotages of the power system. Different stages of power systems protection against physical attacks are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The order of protecting actions against physical attacks on power transmission systems.

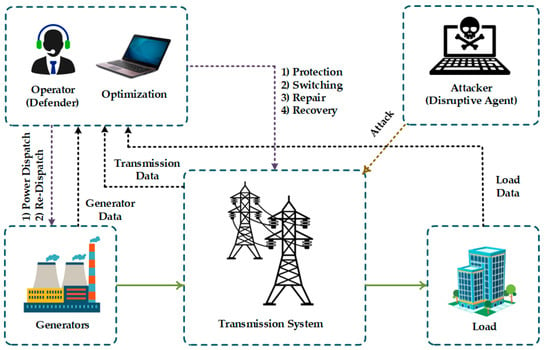

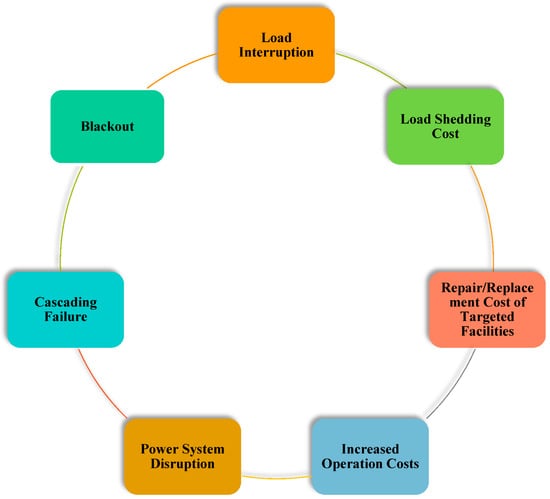

The conceptual diagram for power systems protection against physical attacks on power transmission systems is illustrated in Figure 4. According to this figure, the system operator monitors power systems conditions to reduce the loss of loads due to potential physical attacks. The adverse impacts of physical attacks are illustrated in Figure 5 which can be from a loss of load to a blackout.

Figure 4.

Conceptual diagram for protecting power systems against physical attacks on power transmission systems.

Figure 5.

Different implications of physical attacks on power transmission systems.

In the literature, many research studies have been accomplished related to power systems protection against physical attacks on TLs. Various methods have been adopted to mitigate the impacts of physical attacks on power systems. However, research studies have not been limited to test systems. A number of such research studies have focused on the vulnerability of real systems against physical attacks. The North American power transmission grid has been studied in [17] to distinguish its vulnerability against targeting the TLs. A risk-based approach has been proposed to manage the risk associated with the problem. In [18], the possible damages to the North American power grid by multiple attacks on transmission systems with high betweenness and high degree have been highlighted.

This paper deals with the previous research studies in the context of intelligent physical attacks in power systems. The proposed approaches in the literature for power systems protection are categorized and reviewed in detail. The impacts of physical attacks on cascading failures and blackouts, which are critical issues in power systems, are also reviewed. The previous research studies related to the expansion planning of power grids under physical attacks are discussed. In addition, physical attacks in distributed and reconfigurable grids and also the contribution of DG units to enhance the reliability of power systems against physical attacks are discussed. The restoration time of targeted components, as well as the unserved energy cost considered in the literature, are also studied in this paper. The test systems and objective functions and related models considered in the literature are also focused on in this review paper.

The paper is continued as follows. Section 2 discusses the adverse impacts of physical attacks on power systems, including potential load interruptions, the cost of the unserved load, cascading failures, and blackouts. The existing strategies to mitigate physical attacks on power systems are given in Section 3. In this section, probable attack characteristics, uncertainty considerations, power systems restoration after physical attacks, expansion planning, DG units, and reconfigurable systems are outlined as defense strategies against such destructive attacks. Section 4 focuses on defending objective functions against physical attacks on power systems. This section investigates single-objective, multi-objective, competitive, and multi-level optimization models related to power systems protection against physical attacks. Finally, conclusions are provided in Section 5.

2. Adverse Impacts of Physical Attacks on Power Systems

A physical attack on TLs may have different adverse impacts, such as load interruption, imposing unserved energy costs, cascading failures, etc. The system operator should estimate such impacts and optimize the power systems operation based on them. In the following, these adverse impacts are discussed.

2.1. Load Interruptions

The simplest adverse impact of a physical attack on TLs is load interruption. Some research studies [13,19,20,21] have minimized the amount of unserved energy as a single-objective model, whereas some other research studies have considered the unserved load as one of the objectives in a bi-objective [6] or a tri-objective [22] model. In addition, the loss of load in multi-level models has also been accomplished in the literature [23,24]. The methods proposed in the literature to minimize the amount of the unserved load are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

The approaches used to minimize load interruptions.

2.2. Unserved Load Costs

Imposing unserved load costs to power systems is a destructive impact of physical attacks on TLs. In a wide number of research studies, a fixed cost has been considered for lost loads, namely the penalty cost of unserved loads. In this regard, $1000/MWh [33] and $1500/MWh [6,34] have been considered for unmet demands resulting from targeting TLs by physical attacks. The variable cost for the loss of load has been considered in a research study for the value of the lost load, namely $80–120/MWh in [35]. Furthermore, in [36], the unserved load costs for both the power and gas loads have been considered as $1000/MWh and $200/Sm3 (standard cubic metric), respectively. Although, some other research studies [12,14,15,23,24,26,31,37,38] have considered unserved load cost, its value has not been mentioned.

2.3. Cascading Failures

Physical attacks may cause cascading failures in TLs due to the interdependencies in transmission systems [39,40]. In addition, cascading failures are the major reason for blackouts in power systems [41]. In a physical attack, the attacker’s aim may be cascading failures, which is the most destructive result for power systems. The cascading failure impacts due to physical attacks have been studied in a number of previous research studies. In [14,37], a stochastic game model based on game theory has been presented to estimate the cascading failure attacks on transmission systems. The attacker aimed to maximize the unmet load by attacking TLs, whereas the defender aimed to minimize the same objective. A limited number of TLs could be destructed and protected by the attacker and the system defender, respectively. In [13], the cascading failure phenomenon in power systems due to sequential physical attacks on TLs has been studied, in which the aim of the attacker was to maximize the load curtailment. In [42], the vulnerability analysis of smart grids to concurrent physical attacks on transmission systems has been assessed. The multi-attack combinations were discussed from the viewpoint of the loss of generation power and time to reach the steady-state to identify the strongest attack combination (which leads to blackout) An attack combination is a set of TLs, which are concurrently or orderly targeted by the attacker. Furthermore, in [43], a Q-Learning-based approach has been used to evaluate the vulnerability of smart grids to sequential attacks. In this regard, the objective was to identify a minimal attack sequence that causes a critical system failure through cascading outages. The test power systems studied in the previous research studies, from the viewpoint of the cascading failure effect of physical attacks, are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The detailed highlight of the previous research studies related to occurring the cascading failure phenomenon caused by physical attacks.

3. Defending Actions against Physical Attacks

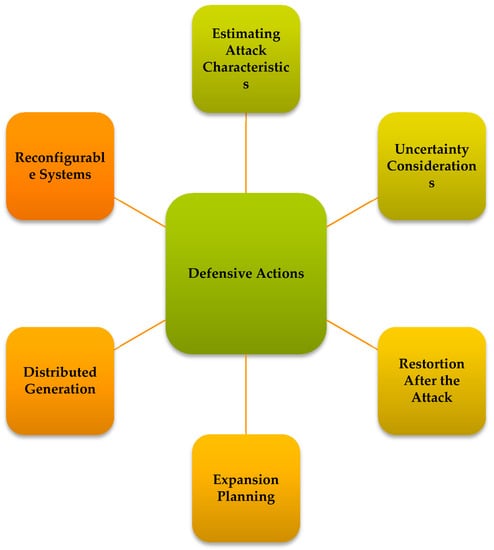

A system operator should overcome the likelihood of physical threat occurrence using the existing methods, such as estimating the characteristics of potential attacks, uncertainty evaluation, restoration of power systems after the attack, considering the impacts of physical attacks on expansion planning problems, installing DG units, and using the line switching to reconfigure them after a physical attack. There are some other approaches to improve the resilience of power systems, such as using the charging capability of electric vehicles in power grids [44,45], timely maintenance of generation units to reduce their failure probability [46], integrating energy systems to increase the energy options [47], demand-side flexibility to supply more important loads during the restoration process [48], and installing energy storage systems to cover critical loads [49]. These existing options are outlined in Figure 6. In the following, such defending actions to overcome the physical attacks are outlined.

Figure 6.

Existing options to protect power transmission systems against physical attacks.

3.1. Detection Methods for Attacks on Power Systems

Different methods have been presented in the literature to detect intentional attacks, including centralized and distributed methods. In centralized detection methods, the collected data from all major components is needed, whereas, in decentralized detection methods, the facilities share information only with their neighbors with physical connections [50]. In [51], a decentralized framework based on the waveform relaxation method has been presented in which power systems were considered as linear time-invariant systems. In this method, detection filters are entirely distributed and only limited knowledge about the system is required. The entire system was sectionalized among dispersed detecting centers, situated at transmission substations. In [52], the main concentration has been on identifying attacks on the Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition (SCADA) system. The proposed framework was based on identifying transient variations in known profiles of probabilistic-dynamical networks with unspecified system conditions. In [53], to overcome the drawback of the existing state estimation method to detect attacks, which was updated minutely, an approach based on the support vector domain has been presented, which was updated secondly. The presented method needed limited information about the characteristics of the attack and was based on dynamic changes of variables to identify affected signals compared to main signals in the normal operating condition. In [54], a bi-level model based on a sensitivity factor of changes in the lines’ flow has been introduced to detect the most damaging and unpredictable attacks. The upper level identified the attack, whereas the lower level determined the optimal alteration in related measurement devices with the lowest budget.

3.2. Estimating Attack Characteristics

To overcome physical attacks, the system operator should estimate the potential attack characteristics such as singularity/multiplicity of physical attacks and multi-period considerations. In the following, these characteristics of physical attacks are discussed.

- (a)

- Single or Multiple Attacks

The adverse impact of an attack depends on the type of attack from the viewpoint of singularity or multiplicity of such attacks. Table 3 lists the previous research studies based on singularity and multiplicity of physical attacks. As this table shows, various cases exist in the literature from single attack (attack one line) [12,55,56] to multiple attacks on 12 TLs [16,57,58,59]. Some research studies have considered one case for the physical attack, such as 6 lines to be attacked [13,60,61] or 10 lines to be attacked [62], whereas some research studies have considered a range of multiple attacks, such as 5 cases of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 lines to be attack [27].

Table 3.

Attack types (single or multiple attacks) considered in the previous research studies.

- (b)

- Multi-Period Considerations

Multi-period consideration of power system problems leads to a better analysis of the performance of power systems in different stages of an attack. The system defender should evaluate the system condition and accomplish the required actions in different stages, including pre-attack, intra-attack, and post-attack stages. Despite its importance, few research studies have investigated the multi-period considerations. In some research studies [2,28,30], three time periods have been considered for the physical attack problem when multiple lines were targeted. In [36], four time periods have been considered, in which power and gas lines were considered to be physically attacked. In [43], six, eight, and five time periods for three case studies have been considered and TLs were targeted by the attacker. Twelve time periods during the year have been taken into account in [33], in which the lines were considered to be attacked by the interdiction agent. In [13], fourteen time stages have been considered to study the impact of attacking lines on cascading failure phenomenon. In some other research studies, a 24-h horizon has been considered to analyze the impact of attacking TLs [15,26]. Additionally, in [6], 4 × 24 h (four sample seasonal days) have been considered. The highlights of the above-mentioned research studies are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

The multi-period considerations in the previous research studies related to the understudy context.

3.3. Uncertainty Considerations

A defending problem against physical attacks is associated with different uncertainties. The system operator should estimate the potential physical attacks on the transmission systems by considering uncertainties in the attacker’s actions and system conditions. The existing research studies in the literature have dealt with different uncertainties. Some research studies have considered one type of uncertainty, namely uncertainty in the budget for transmission expansion [6,23,24], defended TLs [20,64], investment cost for energy storage [28], attacker resources [32], attacked TLs [25,34], load demand [43], the total number of TLs to be targeted [57], and the amount of load interruption by the attacker [60].

Several research studies have handled two types of uncertainties, including uncertainty in attack budget and restoration duration [15], uncertainty in defender budget and attacker budget [19,27,36], and uncertainty in the maximum number of TLs to be attacked and maximum number of TLs to be defended [31]. Some other research studies have dealt with three types of uncertainty sources in the physical attack problem in power systems, i.e., uncertainty in the defense budget, defense targets, and investment for DG units allocation [30], uncertainty in location, i.e., bus, of installing control center, the maximum number of TLs to be attacked, and load demand [62], and uncertainty in investment for TL switching, the maximum number of TLs allowed to be switchable, and attack budget [63].

Various types of uncertainties have been taken into consideration in some other research studies [68]. Some studies have dealt with four types of uncertainties, namely uncertainty in the maximum number of TLs that are defended, success probabilities of attacks, defense budget, and load demand [2] and the uncertainty in attack resources, defense resources, cyber-attack resources, and the proportion of post-allocated DG units [29]. In [26], five uncertainty sources, i.e., attack budget, attack time, and maximum number of concurrent attacks (maximum number of TLs to be simultaneously attacked), the total capacity of energy storage to be installed, the maximum number of buses for energy storage installation have been taken into account.

Table 5 lists the highlights of the above-mentioned research studies.

Table 5.

The uncertainty considerations in the previous research studies related to physical attacks on power systems.

3.4. System Restoration after Physical Attacks

After physical attacks, restoration of the loss of loads is followed by the system operator, especially the load that has a higher load interruption cost, i.e., the value of the lost load. Restoration duration depends on the intensity and location of physical attacks and also the characteristics of the under-attacked power systems. In some research studies, 1 h has been considered for load restoration after a single attack [12] and multiple attacks [20] on TLs. A number of other research studies have considered 2 h for restoring loads after the physical attack [26]. The uncertainty in restoration duration (2, 3, or 4 h) has been considered in [15]. Table 6 highlights the previous research studies from the viewpoint of the restoration duration of loads after the physical attack on the transmission system.

Table 6.

Considered restoration duration after the physical attack.

3.5. Expansion Planning

Expansion planning problems, particularly transmission expansion planning problems, should consider the system’s resilience against different threats, such as physical attacks. The expansion planning of power systems subjected to physical attacks on TLs decreases the system’s vulnerability against such destructive attacks. Some research studies have been accomplished in this context. A bi-objective model has been introduced in [6], in which one objective was energy not supplied, and the other objective was the total annual cost. This cost included the investment cost for new TLs and energy storage, the average cost of unserved loads, and the operation cost of generators and energy storage. In [23,24], a tri-level model for transmission expansion of power systems considering physical attacks on grid lines has been presented. The proposed approach considered the impact of physical attacks on both existing as well as planned TLs for construction. The results showed a significant improvement in the grid vulnerability. In [33], a bi-level model was introduced for generation and transmission expansion planning of power networks considering the level of immunity of TLs against physical attacks. The upper level is related to the attacker with a limited budget to destruct transmission systems to maximize the unserved load, whereas, in the lower level, the operator minimizes the Expected Energy Not Supplied (EENS) and total cost (the total cost included the investment, operation, and EENS costs). In [63], the investment for capacity expansion planning and switch placement are simultaneously optimized to enhance the resilience of reconfigurable power systems against physical attacks. A tri-objective model was introduced, in which the system planner, the attacker, and the operator optimize the total investment, system disruptions, and system performance loss after the attack, respectively.

Additionally, some research studies have incorporated the reinforcement of existing lines in the expansion planning problem. In [22], a tri-objective model has been presented based on expected load shed, expected cost of load shed, and investment cost for TLs and switches. In [25], a bi-objective model based on load shedding minimization (with the importance degree of system loads) as well as investment cost minimization has been introduced under the physical attack consideration with a limited budget of the attacker. Moreover, in [34], a risk-constrained transmission expansion planning problem subjected to the vulnerability aspect of the system against physical attacks on TLs has been introduced. The total costs, including the investment cost and the unserved energy cost, were minimized considering risk management. In Table 7, the previous research studies related to expansion planning of power systems considering system protection against physical attacks are highlighted. As this table shows, sensitivity analysis of investment cost has been accomplished in all the previous research studies.

Table 7.

Detailed highlighted of the previous research studies in the context of expansion planning of power systems with physical attack considerations.

3.6. DG Units

Load interruption is another adverse impact of physical attacks. After a physical attack and during the restoration process of unmet loads, DG units, such as renewable energy sources, diesel generators, and energy storage systems, can fully or partially supply the unserved loads. The role/application of DG units in reinforcing power networks against deliberate damages (by enhancing power grids flexibility) has been outlined in the literature. The role of energy storage systems to mitigate the impact of physical attacks has been highlighted in some research studies. A tri-level model was presented in [15], to defend TLs integrated with energy storage systems. The upper level dealt with minimizing the operation costs of generators and energy storage and also the unserved energy cost. The middle level focused on maximizing the unserved energy caused by targeting some TLs from the physical attacker. Finally, the lower level minimizes the unmet energy cost during the restoration process under different restoration duration scenarios. Moreover, in [26], the objective was to determine the optimal sizing of energy storage and improve the system’s resilience against physical attacks on multiple TLs, through a tri-level multi-period model. The impacts of the maximum number of attacked TLs and the maximum number of buses for energy storage installation have been outlined. In [28], investment for energy storage has been focused on using a multi-objective model based on the minimum unserved load and total costs (the total costs included the investment cost for energy storage and production cost of generators) with a sensitivity analysis for the investment cost.

A number of other research studies have focused on using DGs to improve the system’s resilience against physical attacks. In [27], the resilience of reconfigurable diesel-integrated radial distribution systems against physical attacks on TLs through a tri-level model has been improved. On the outer level, the system defender tried to minimize the load shedding by reconfiguration, in the middle level, the attack scenario with the maximum damage was investigated, and on the bottom level, the optimal islanding operation based on the minimum load interruption was investigated. In [29,30], a model has been evaluated for power systems protection against multiple and multi-period physical attacks on TLs during seven time periods after installing diesel generators. The problem was formulated in three levels that were related to the system defender, attacker, and operator. The aims of the levels were allocating a defensive budget on TLs and locating pre-allocated diesel generators, identifying the critical targets based on the maximal unserved demand, and optimal power flow for the healthy part of the power system, respectively. In [36], gas-electric energy systems incorporating the gas storage system were protected against physical attacks on electric and gas lines using a tri-level robust model. The outer level was related to the planner to reinforce the critical components, the middle level dealt with identifying the critical facilities by the attacker, and the bottom level was related to minimizing the total cost including the operation costs and the unserved cost of power and gas loads. Table 8 lists the detailed highlight of the previous research studies.

Table 8.

Detailed highlighted of the previous research studies related to the role of DG units in supplying unserved loads after physical attacks.

3.7. Reconfigurable Systems

Reconfiguration is an effective way to decrease the unserved energy after a physical attack. Protecting reconfigurable power systems against physical attacks has been investigated in some research studies. In [7], the IEEE RTS system (version 1996) has been considered as a reconfigurable power system subjected to attack on 2, 4, and 6 TLs. A bi-level model was presented to protect the system, in which the attacker tried to impose the maximum loss of load, whereas the system defender tried to retain the load interruption at a minimal level by re-dispatching the resources as well as line switching, i.e., the system reconfiguration. In [27], the resilience of reconfigurable radial distribution systems incorporating diesel generators against physical attacks on TLs has been studied through a tri-level model. The outer level was related to the defender, which minimizes the load interruption by reconfiguration capability of the grid, in the middle level, the attack scenario with the maximum damage was investigated, and in the bottom level, the optimal islanding operation based on the minimal unserved load was searched. IEEE 33-bus and IEEE 94-bus radial distribution systems were tested by attacking 1–5 TLs. Moreover, in [63], a modified version of the IEEE 14-bus system was considered to be planned for transmission expansion and switch installation to enable the reconfigurability of TLs against concurrent physical attacks on six TLs. The sensitivity analysis of the investment cost for TLs and switches was accomplished. Moreover, the uncertainty in attack resources was considered.

4. Objective Functions and Optimization Methods

In the literature, different objective functions have been considered for protecting power systems against physical attacks. Some research studies have introduced single-objective optimization models, such as load interruption [13], cost of unserved loads [37], investment cost for protection power systems’ components [65], and the sum of the operation cost and the cost of the loss of load [38]. A number of other research studies have focused on multi-objective models, including bi-objective [64] and tri-objective [22] models. Different objectives have been considered through multi-objective models in the previous research studies, such as load interruption, unserved load cost, operation cost, investment cost, etc. Multi-level models have been presented in some other research studies including bi-level [58] and multi-level [32] models. Interaction between the system operator and attacker, and the actions of the operator before and after the physical attack have been investigated by bi-level models, whereas tri-level models were introduced to model the interaction among the system planner, attacker, and system operator. Table 9 categorizes the previous research studies from the viewpoint of the objective function.

Table 9.

The categorization of the previous research studies from the objective function point of view.

4.1. Single-Objective Models

Some research studies have investigated the physical attack problem with the aim of minimum unserved load for attacking lines [13,19,20,21]. The unserved load cost was the objective of some other research studies to protect power systems against attacking lines [12,37]. In [38], the sum of operation cost and the cost of the loss of load has been considered as the objective function [38]. The investment cost for protection was considered in [65] for TLs protection. The vulnerability of the power network in the case of physical attacks on transmission systems has been investigated in a wide number of research studies [42,43,55,66]. Detailed highlights of the above-mentioned references, which have adopted a single-objective model are presented in Table 10. As this table shows, the optimization models have been solved by optimization algorithms, such as game theory [12,20], Column-and-constrains generation (C&CG) algorithm [21], greedy algorithm [38], or software tools, such as GAMS software [66], MATLAB toolboxes [13,37], Python [19], cascading failure simulators [42,43], and CPLEX Optimization Studio [65]. Most of these research studies have adopted IEEE RTS and IEEE 30-bus test systems for numerical simulation.

Table 10.

The detailed highlight of the previous research studies with single-objective optimization.

4.2. Multi-Objective Models

Considering more than one objective function can lead to a better system optimization against physical attacks. A number of research studies have introduced bi-objective models to mitigate the implications of physical attacks on TLs [6,25,28,34]. Tri-objective models have been employed in [22] to defend power systems against such attacks. Table 11 lists the detailed highlights of the previous research studies, which have adopted multi-objective models for power systems protection against physical attacks. These optimization models were solved using GAMS software [6,25,28,34] and branch-and-cut software [22].

Table 11.

Detailed highlights of the previous research studies with multi-objective optimization.

4.3. Competitive Models

Competitive models for simulating the competitiveness between the system operator and physical attacker have been focused on in some research studies. In such models, the system operator predicts the behavior of the attacker in targeting TLs. These optimization models were solved using optimization methods, including genetic algorithm [16], game theory [64], Markov decision processes [56] and Spectral graph theory [67], and software tools, including GAMS software [60], MATPOWER toolbox [14], and CPLEX Optimization Studio [63]. Table 12 lists the detailed highlights of these research studies.

Table 12.

Detailed highlights of the previous research studies with competitive optimization models.

4.4. Multi-Level Models

Some research studies have introduced multi-level models for power systems protection against deliberate outages of TLs caused by an attacker. Bi-level models were presented for interaction between attacker and defender/operator, whereas tri-level models were introduced for interactions among planner, attacker, and operator. In some research studies, bi-level models have been introduced to mitigate the implications of physical attacks on TLs [2,7,33,35,57,58,62]. Tri-level model have been focused on some other research studies for attacking TLs [15,23,24,26,27,29,30,31,32,59,61] and electric and gas lines [36]. Table 13 and Table 14 outline the previous research studies, which have, respectively, adopted bi-level and tri-level models to mitigate the impacts of physical attacks on power systems. As this table shows, these optimization models have been solved by optimization methods, including genetic algorithm [7] and C&CG method [26], and software tools, such as MATLAB toolbox [2,31] and GAMS software [33,57].

Table 13.

Detailed highlights of the previous research studies with bi-level optimization models.

Table 14.

Detailed highlights of the previous research studies with tri-level optimization models.

5. Conclusions

This paper reviews the previous research studies related to existing strategies for protecting power systems against physical attacks on power Transmission Lines (TLs). In this regard, defensive approaches and technologies to overcome the deliberate and destructive actions of attackers were outlined. The adverse impacts of physical attacks, such as causing load interruption, imposing unserved load costs, repair or replacement costs of targeted facilities, and cascading failures (to increase the load interruption or blackout), were discussed. The defensive actions, such as reconfiguration of power TLs, installing energy storage systems and DG units, system restoration after the attack, and defensive-based expansion planning, were outlined. The objective functions, optimization methods, understudied systems, etc., were also reviewed in this paper. The existing gaps in the literature are highlighted as follows:

- The role of different players in a defensive plan against physical attacks has not been well-discussed. Each defensive plan includes several players, such as the system planner, system operator, disruptive agent, customers, policy-maker, power grid, etc.

- Dynamic aspects of power systems, when TLs are targeted by physical attacks, have not been studied.

- The cost of the unserved load has not been well-focused on in the literature of the understudied context.

- Few research studies have considered a practical multi-period time horizon. Most of them have been focused on a single time interval. Multi-period time horizons should be more studied in future research studies.

- Multi-objective models mainly include bi-objective models, whereas, in practical problems, more than two objectives may be needed to be taken into account.

- Considerations of distributed energy resources only have included diesel generators, whereas renewable energy sources will be the main distributed energy systems in the near future.

The above-mentioned gaps are needed to be focused on in future research studies. In future studies, protection strategies against physical attacks on the other components of power systems, including generation units, buses, substations, transformers, circuit breakers, protective devices, etc., will be discussed. Moreover, technical details of security constraints considered in the literature will be reviewed.

Author Contributions

O.S.: Writing—original draft; B.M.-I.: Investigation and validation, resources, conceptualization, writing—review and editing; F.M.: Formal analysis, investigation and validation, conceptualization, writing—review and editing; Z.A.-M.: review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bompard, E.; Huang, T.; Wu, Y.; Cremenescu, M. Classification and trend analysis of threats origins to the security of power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2013, 50, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, D.; Diao, R.; Wang, Z. Robust optimization for transmission defense against multi-period attacks with uncertainties. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 121, 106154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Nazri, G.A.; Saif, M. A fast fault detection and identification approach in power distribution systems. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Power Generation Systems and Renewable Energy Technologies, Istanbul, Turkey, 26–27 August 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bompard, E.; Gao, C.; Masera, M.; Napoli, R.; Russo, A.; Stefanini, A.; Xue, F. Approaches to the Security Analysis of Power Systems: Defence Strategies Against Malicious Threats; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rashidzadeh, R. An Overview of IoT-Enabled Monitoring and Control Systems for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2021, 24, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, H.; Latify, M.A.; Reza Yousefi, G. Optimal Coordinated Expansion Planning of Transmission and Electrical Energy Storage Systems under Physical Intentional Attacks. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila, E.L.; López-Lezama, J.M.; Muñoz-Galeano, N. An Approach to the Power System Interdiction Problem Considering Reconfiguration. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 2313–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Wang, X.; Tolbert, L.M.; Li, F.; Peng, F.Z.; Ning, P.; Amin, M. A resilient real-time system design for a secure and reconfigurable power grid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2011, 2, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, Å.J. Using graph models to analyze the vulnerability of electric power networks. Risk Anal. 2006, 26, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rashidzadeh, R. Impact of stealthy false data injection attacks on power flow of power transmission lines—A mathematical verification. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 142, 108293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Sanjari, M.; Saif, M. A Real-Time Blockchain-Based Multifunctional Integrated Smart Metering System. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Kansas Power and Energy Conference (KPEC), Manhattan, KS, USA; 2022; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar, M.H.; Kheradmandi, M.; Pirayesh, A. A Linear Game Framework for Defending Power Systems against Intelligent Physical Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 6592–6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, B.; Xie, K.; Chao, H.; Zhou, P. A Sequential Coordinated Attack Model for Cyber-Physical System Considering Cascading Failure and Load Redistribution. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration, EI2, Beijing, China, 20–22 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Li, P. Cascading Failure Attacks in the Power System. In Security of Cyber-Physical Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K.; Wang, Y.; Shi, D.; Illindala, M.S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. A Resilient Power System Operation Strategy Considering Transmission Line Attacks. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 70633–70643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.M.; Fernández, F.J. A genetic algorithm approach for the analysis of electric grid interdiction with line switching. In Proceedings of the 2009 15th International Conference on Intelligent System Applications to Power Systems, Curitiba, Brazil, 8–12 November 2009; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff, J.S.; Restrepo, C.E.; Zimmerman, R. Risk-management and risk-analysis-based decision tools for attacks on electric power. Risk Anal. 2007, 27, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, R.; Crucitti, P.; Albert, R.; Latora, V. Modeling cascading failures in the North American power grid. Eur. Phys. J. B 2005, 46, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Georgiadis, D.; Ng, T.S.; Sim, M. An optimization model for power grid fortification to maximize attack immunity. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 99, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Dong, Z.Y.; Hill, D.J.; Xue, Y.S. Exploring reliable strategies for defending power systems against targeted attacks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2011, 26, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Yao, L.; Li, F. A multi-uncertainty-set based two-stage robust optimization to defender–attacker–defender model for power system protection. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 169, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, M.; Arroyo, J.M.; Alguacil, N. Vulnerability-constrained transmission expansion planning: A stochastic programming approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2007, 22, 1436–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, H.; Latify, M.A.; Yousefi, G.R. Tri-level transmission expansion planning under intentional attacks: Virtual attacker approach—Part I: Formulation. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2019, 13, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, H.; Latify, M.A.; Yousefi, G.R. Tri-level transmission Expansion planning under intentional attacks: Virtual attacker approach—Part II: Case studies. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2019, 13, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, N.; Carrión, M.; Arroyo, J.M. Transmission network expansion planning under deliberate outages. In Handbook of Power Systems I. Energy Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 365–389. ISBN 9780947649289. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K.; Shi, D.; Li, H.; Illindala, M.; Peng, D.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z. A Robust Energy Storage System Siting Strategy Considering Physical Attacks to Transmission Lines. In Proceedings of the 2018 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Fargo, ND, USA, 9–11 September 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Bie, Z. Tri-level optimal hardening plan for a resilient distribution system considering reconfiguration and DG islanding. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Sepahvand, M.; Amraee, T.; Nikoofard, A. A Game Framework to Confront Targeted Physical Attacks Considering Optimal Placement of Energy Storage. In Proceedings of the 2019 Smart Grid Conference (SGC), Tehran, Iran, 18–19 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T. A tri-level optimization model for power grid defense with the consideration of post-allocated DGs against coordinated cyber-physical attacks. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 130, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T. Robust Optimization for Microgrid Defense Resource Planning and Allocation against Multi-Period Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 5841–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Huang, S.; Zhang, T. Optimal deception strategies in power system fortification against deliberate attacks. Energies 2019, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Wang, L. An improved defender-attacker-defender model for transmission line defense considering offensive resource uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 2534–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, H.; Latify, M.A.; Yousefi, G.R. Coordinated generation and transmission expansion planning for a power system under physical deliberate attacks. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 96, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.M.; Alguacil, N.; Carrión, M. A risk-based approach for transmission network expansion planning under deliberate outages. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2010, 25, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ren, K.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Optimal budget deployment strategy against power grid interdiction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings—IEEE INFOCOM, Turin, Italy, 14–19 April 2013; pp. 1160–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wei, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Qiu, F.; Correa-Posada, C.M.; Mei, S. Robust Defense Strategy for Gas-Electric Systems Against Malicious Attacks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 2953–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Salinas, S.; Li, M.; Li, P.; Loparo, K.A. Cascading Failure Attacks in the Power System: A Stochastic Game Perspective. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 2247–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bier, V.M.; Gratz, E.R.; Haphuriwat, N.J.; Magua, W.; Wierzbicki, K.R. Methodology for identifying near-optimal interdiction strategies for a power transmission system. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2007, 92, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M. Review on modeling and simulation of interdependent critical infrastructure systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014, 121, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.J.; Cao, Y.J.; Wang, G.Z.; Ding, L.J. Analysis of cascading failure in electric grid based on power flow entropy. Phys. Lett. Sect. A Gen. At. Solid State Phys. 2009, 373, 3032–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, Y.; Warnier, M.; Kooij, R.E.; Brazier, F.M.T. A robustness metric for cascading failures by targeted attacks in power networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control, Evry, France, 10–12 April 2013; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.; Ni, Z. Vulnerability analysis for simultaneous attack in smart grid security. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Power and Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 23–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; He, H.; Zhong, X.; Tang, Y. Q-Learning-Based Vulnerability Analysis of Smart Grid against Sequential Topology Attacks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, O.; Nazari-Heris, M.; Abapour, M.; Taheri, S.S.; Zare, K. Improving reliability of distribution networks using plug-in electric vehicles and demand response. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2019, 7, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, O.; Oshnoei, A.; Mohammadi-ivatloo, B.; Vahidinasab, V. A comprehensive review on electric vehicles smart charging: Solutions, strategies, technologies, and challenges. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, O.; Mohammadpour Shotorbani, A.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Sadiq, R.; Hewage, K. Risk-averse maintenance scheduling of generation units in combined heat and power systems with demand response. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 107960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, O.; Oshnoei, A.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Vahidinasab, V. Concept, Definition, Enabling Technologies, and Challenges of Energy Integration in Whole Energy Systems To Create Integrated Energy Systems. In Whole Energy Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghian, O.; Moradzadeh, A.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Vahidinasab, V. Active Buildings Demand Response: Provision and Aggregation. In Active Building Energy Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 355–380. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghian, O.; Oshnoei, A.; Khezri, R.; Muyeen, S.M. Risk-constrained stochastic optimal allocation of energy storage system in virtual power plants. J. Energy Storage 2020, 31, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Guerrero, J.M.; Xie, P.; Han, R.; Vasquez, J.C. Brief Survey on Attack Detection Methods for Cyber-Physical Systems. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 5329–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, F.; Pasqualetti, F.; Bullo, F. Distributed detection of cyber-physical attacks in power networks: A waveform relaxation approach. In Proceedings of the 2011 49th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing, Allerton, Monticello, IL, USA, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 1486–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Do, V.L.; Fillatre, L.; Nikiforov, I. A statistical method for detecting cyber/physical attacks on SCADA systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Control Applications (CCA), Juan Les Antibes, France, 8–10 October 2014; pp. 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, W.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Yuan, K.; Wang, Y. Detection Scheme against Cyber-Physical Attacks on Load Frequency Control Based on Dynamic Characteristics Analysis. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 13, 2859–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shahidehpour, M.; Alabdulwahab, A.; Abusorrah, A. Bilevel Model for Analyzing Coordinated Cyber-Physical Attacks on Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 7, 2260–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zio, E.; Golea, L.R. Analyzing the topological, electrical and reliability characteristics of a power transmission system for identifying its critical elements. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2012, 101, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.Y.T.; Yau, D.K.Y.; Lou, X.; Rao, N.S.V. Markov game analysis for attack-defense of power networks under possible misinformation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 1676–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, A.; Arroyo, J.M.; Alguacil, N. Analysis of electric grid interdiction with line switching. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2010, 25, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zeng, B. Vulnerability analysis of power grids with line switching. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 2727–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zhao, L.; Zeng, B. Optimal power grid protection through a defender-attacker-defender model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014, 121, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.M.; Galiana, F.D. On the solution of the bilevel programming formulation of the terrorist threat problem. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2005, 20, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Shi, L. Modeling an Attack-Mitigation Dynamic Game-Theoretic Scheme for Security Vulnerability Analysis in a Cyber-Physical Power System. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 30322–30331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraati, M.; Aref, Z.; Latify, M.A. Vulnerability Analysis of Power Systems under Physical Deliberate Attacks Considering Geographic-Cyber Interdependence of the Power System and Communication Network. IEEE Syst. J. 2018, 12, 3181–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Sansavini, G. Optimizing power system investments and resilience against attacks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 159, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Shi, L.; Yao, L.; Masoud, B. Electric grid vulnerability assessment under attack-defense scenario based on game theory. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, Hong Kong, China, 8–11 December 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nezamoddini, N.; Mousavian, S.; Erol-Kantarci, M. A risk optimization model for enhanced power grid resilience against physical attacks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 143, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shahidehpour, M.; Alabdulwahab, A.; Abusorrah, A. Analyzing locally coordinated cyber-physical attacks for undetectable line outages. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar, A.; Meza, J.; Donde, V.; Lesieutre, B. Optimization strategies for the vulnerability analysis of the electric power grid*. SIAM J. Optim. 2010, 20, 1786–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F. Emerging challenges in smart grid cybersecurity enhancement: A review. Energies 2021, 14, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).