Chile is experiencing deep structural transformations aimed at strengthening climate action and community participation through institutional, legal, and likely constitutional changes. This is strongly related to the ongoing political crisis, which was in evidence in October 2019, challenging traditional Chilean institutions, the political parties’ regime, and the neoliberal system designed and implemented during the dictatorship (1973–1990). Along with demands for better health services, public education, a fairer retirement system, and higher salaries—all issues related to deep structural inequalities—increasing community participation, concern for the natural environment, and climate change have been at the forefront of social demands, as well as calls for an effective decentralization of the country [

1,

2]. In this complex scenario, one of the main outcomes of this crisis has been the unprecedented possibility of writing a new constitution through an entirely democratic process. However, despite the depth, magnitude, and pace of these changes, it is unclear how the general population perceives their role in this new Chile, especially regarding climate change. This article reports the results of a survey aimed at exploring to what extent these structural transformations are also associated with cognitive and relational changes, thus reflecting a new understanding of both the environment and community participation in Chilean society.

This study is part of a wider transdisciplinary research project, whose main goal was to contribute to the community construction of constitutional bases for a society resilient to ongoing and future climate scenarios, conducted during 2020–2021 in Punta Arenas. This is the southernmost city of the American continent, the capital of the Magellan and the Chilean Antarctic Region, located on the Strait of Magellan in Patagonia. The decision to select Punta Arenas was threefold. First, the Region of Magellan is one of the areas most affected by climate change, and it is already experiencing dramatic changes, especially in the snow covering and temperature; second, it is a highly isolated region that has had to deal historically with multiple difficulties associated with the centralized Chilean State; third, diverse studies have shown that its inhabitants express a strong regional ecological identity, which integrates their particular and historical relationship with the natural environment of the region, and the difficulties of establishing a settlement in such hostile geographic and climatic conditions [

3,

4].

We use the transformation approach to climate change as a framework to analyze the results and the study context. There are different perspectives on transformation [

5]. These include systemic approaches, in which special attention has been paid to the capacities for innovation, adaptation, and learning of socioecological systems [

6,

7], as well as to the transitions of sociotechnical systems [

8]. On the other hand, structural approaches address transformations as historical processes and observe radical changes of a political or economic nature in social relations determined by power [

9,

10]. Finally, the enabling approaches integrate the previous two, paying attention to the agency capacity and the transformations’ direction and objectives [

11,

12,

13]. Here, transformation is defined as a change in the fundamental attributes of natural and human systems [

14].

Transformations are collective or individual adaptations. They can be planned, but require autonomous adaptations by individuals and organizations [

15]. In this sense, transformations are dynamic and complex processes requiring simultaneous changes in different systems [

5,

16]. Transformation also refers to a broad and often irreversible set of changes that imply profound innovation in the economic, technological, and social environments. These include changes in the way of thinking, decision-making, actions, behavior, power structures, governance systems, values, predefined goals, how energy is used and produced, and how infrastructure and natural resources are managed [

17,

18]. Accordingly, transformation can unfold in four domains [

16]: (1) cognitive (values and thinking), including significant shifts in societal beliefs, norms, values, and understandings, which may manifest as radically new concepts, ways of viewing the world or notions of progress; (2) structural (institutions and governance), referring to significant shifts in institutional arrangements and governance processes, such as major policy change, institutional reform, or new feedback and accountability mechanisms; (3) relational (interactions among actors), involving significant shifts in relationships between actors and institutions, such as moving from siloed to integrated decision-making processes, new collaborations among diverse stakeholders that enhance science–policy–practice linkages, or new accountabilities between public, private and civil society actors; and (4) functional (system behavior/outcomes), including significant changes in the behavior and function of a system, for example, the diffusion of innovative sustainability practices, or changes in technology that reshape human activities of communication, production, and consumption. This may include the significant technological or practical advances that disrupt the status quo and allow opportunities for more radical changes and sustainable outcomes [

18]. Many of these domains are mutually reinforcing, and multiple domains may need to change for transformation to occur [

5].

1.1. Structural Transformations toward Climate Action

The unprecedented constitutional process that started in November 2019 occurs in a post-Paris Agreement context, with severe climate change impacts already affecting the country (e.g., a 12-year mega-drought and massive wildfires) and numerous biodiversity threats. Many people with an environmental agenda were elected to be part of the constitutional assembly, representing the interest in a profound transformation of the human–nature relationship [

23,

24]. As such, a considerable number of constitutional articles in the draft phase, which will be submitted to a referendum, consecrate environmental principles related to environmental rights (e.g., the right to environmental health, the human right to water, the rights of nature, animals’ wellbeing right), environmental state duties, and an environmental institution framework. Additionally, the draft recognizes “the duty of the State to adopt actions for the prevention, adaptation, and mitigation of risks, vulnerabilities, and effects caused by the climate and ecological crisis”.

Among the principles, the draft states just climate action in view of adopting the best possible decisions in the long term, articulating: 1. incremental actions that seek to gradually make progress without affecting the essential attributes of social–ecological systems to achieve mitigation and adaptation goals, without ever going back (principle of non-regression) and progressively increasing ambition (principle of progressivity), as stopping means regressing; 2. transformative actions that imply radical changes in the attributes of social–ecological systems, either expanding, reorganizing, redirecting, or innovating in terms of beliefs, norms, and values, institutional arrangements, production and consumption systems, relationships among actors, etc. [

19,

25,

26].

If the assembly’s proposal is approved in the referendum, this could be one of the first constitutions addressing climate change more deeply, holistically, and transversally, with a solid pro-environmental component. This would help to overcome some of the contradictions and limitations of the Constitution of 1980 created during the dictatorship (e.g., the permanent tension between the right to a healthy environment, the property right and the freedom to exercise any economic activity) and establish a more ambitious and transversal form of participation through mechanisms of direct democracy (it will also be the first constitution in Chile that arises from an entirely democratic process; the first legal document prepared under the parity rule between women and men; and the first one with seats reserved for indigenous communities).

It is important to note that the Chilean Higher Courts (Courts of Appeals and Supreme Court) have also played a key role in advancing these changes. For example, some cases submitted through the constitutional protection remedy in connection with climate change have been brought as a consequence of the eventual violation of rights caused by the increase in magnitude and frequency of extreme events that would be associated with climate change, such as floods, fires, and algal blooms. At the same time, the Tribunals have reinforced the importance of participation, information, and justice access according to present environmental legislation and the Rio Declaration of 1992 [

27].

The emphasis on participation in all these structural transformations could also be interpreted as a response to what scholars have been pointing out for many years: the reduced influence of citizens in Chilean environment-related institutions and regulations through mechanisms aimed at keeping people informed or just collecting the community’s opinions [

28,

29,

30,

31]. In most cases, these procedures have not deterred authorizations to develop private initiatives that have jeopardized communities’ wellbeing and the environment’s protection. This situation has been at the core of multiple socio-environmental conflicts, including those associated with the environmental impact assessment system (EIA). Several studies [

32,

33,

34] have questioned its legitimacy, as the citizens’ participation mechanism, although compulsory, is symbolic, non-binding, and insufficient. In fact, legally, the incidence of local communities is restricted. Although the environmental, institutional framework considers public participation in the management instruments (policies, plans, standards, environmental impact evaluation), the implementation of each participation system instrument is unequal. This is the main source of socio-ecological conflicts. For instance, environmental impact evaluations are generally made without considering the territorial planning context. Consequently, local communities do not have a chance to influence critical issues such as land use, what type of projects or development are the most adequate for the place they live, which ones are more compatible with their territorial vocation, or the type and degree of impacts they are willing to tolerate.

All of this has increased the lack of social legitimacy of the environmental institutions and the pressure to change them, which is at the core of the ongoing constitutional debates [

35]. Thus, Chile is experiencing a historic, profound, and unprecedented transformational process, at least in the structural dimension, that could create the conditions to reshape the relationship between people and public institutions at multiple levels [

21].

1.2. Relational and Cognitive Transformations in Community Participation

As pointed out by the IPCC [

14,

17], limiting global warming to 1.5 °C will require unprecedented societal transformations to implement a strong, rapid, and sustained reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, as well as locally relevant adaptation strategies, all of which demands broader community participation at multiple levels. Certainly, all the structural changes occurring in Chile are creating a positive context to address these challenges. However, transforming institutions, rules and regulations alone does not guarantee a broader engagement of local communities in more ambitious, committed, and lasting climate action, even with a growing environmental awareness and climate change concern in the population [

13]. In the case of Chile, power asymmetries, a profound lack of trust in the political system, and social inequalities have severely impacted how people perceive the possibilities to influence or be part of climate-related decisions and actions [

36,

37,

38,

39].

On the one hand, environmental organizations and demonstrations have proliferated in Chile in the context of the multiple socio-environmental conflicts occurring in the country in the last decade [

40,

41], and climate change-related organizations have formed important national networks (e.g., Civil Society for Climate Action SCAC) likely reflecting the growing concern on this issue among the population [

42]. On the contrary, according to the Third National Survey on the Environment and Climate Change [

43], less than 5% of the population had participated in initiatives related to environmental issues, despite very high levels of concern about climate change impacts and the state of the environment. Moreover, the presence of environmental organizations in the constitutional assembly might well reflect their capacity to organize themselves and be a legitimate democratic option for this task, but that does not necessarily mean a profound change in the way most Chileans understand community participation (e.g., only 41.5% of the people participated in that election). Thus, this push for more participatory institutions might be another expression of the top-down culture, and the representative and hierarchical type of democracy in which citizens delegate to others most responsibilities (this time to social organizations instead of traditional political parties), rather than a broader interest in actively engaging in environmental decision-making processes or climate action. It might also reflect a particular way of understanding community participation held only by certain political groups, social organizations and academic circles, and not necessarily the general public.

All in all, the literature suggests that along with efforts to improve our understanding of the multiple barriers to developing structural transformations toward a more participatory society, it is paramount to dig deeper into the cognitive and relational changes that are also needed to implement more ambitious climate action. The literature also shows us the importance of innovation in transformation, and how it must operate at collective and individual levels. For decades, Chilean scholars have focused their analysis mainly on institutional, legal, and constitutional limitations, but now structural changes are occurring, or are likely to occur. It is unclear what will happen with the people who are not part of social organizations or political parties regarding how they perceive their role in this new institutional scenario. However, transformational approaches help us to think about how to address the challenges these changes impose on structures, people, and relationships. On the other hand, the transformation framework highlights the importance of addressing these issues, showing the different dimensions and trajectories of change and the need to explore them using an integrative perspective.

1.3. The Case Study: Punta Arenas, the Southernmost City in the World

The Magellan and the Chilean Antarctic Region includes the southern part of Patagonia, the western section of Tierra del Fuego, and the adjacent archipelagos. It covers 132,033 km

2, representing 17.5% of Chile’s surface [

44]. Approximately 50% of the surface corresponds to protected wild areas, including reserves, natural monuments, and national parks, that provide diverse, numerous, and important ecosystem services at local and global levels [

45]. Its current population is 131,592 inhabitants [

46], concentrated mainly in the communes of Punta Arenas, Puerto Natales, and Porvenir, which alone account for 95.5% of the total regional population. Indicators of poverty levels are among the lowest in the country [

47], and inequality indicators are below the national average [

48]. It is one of the country’s regions with the highest level of development.

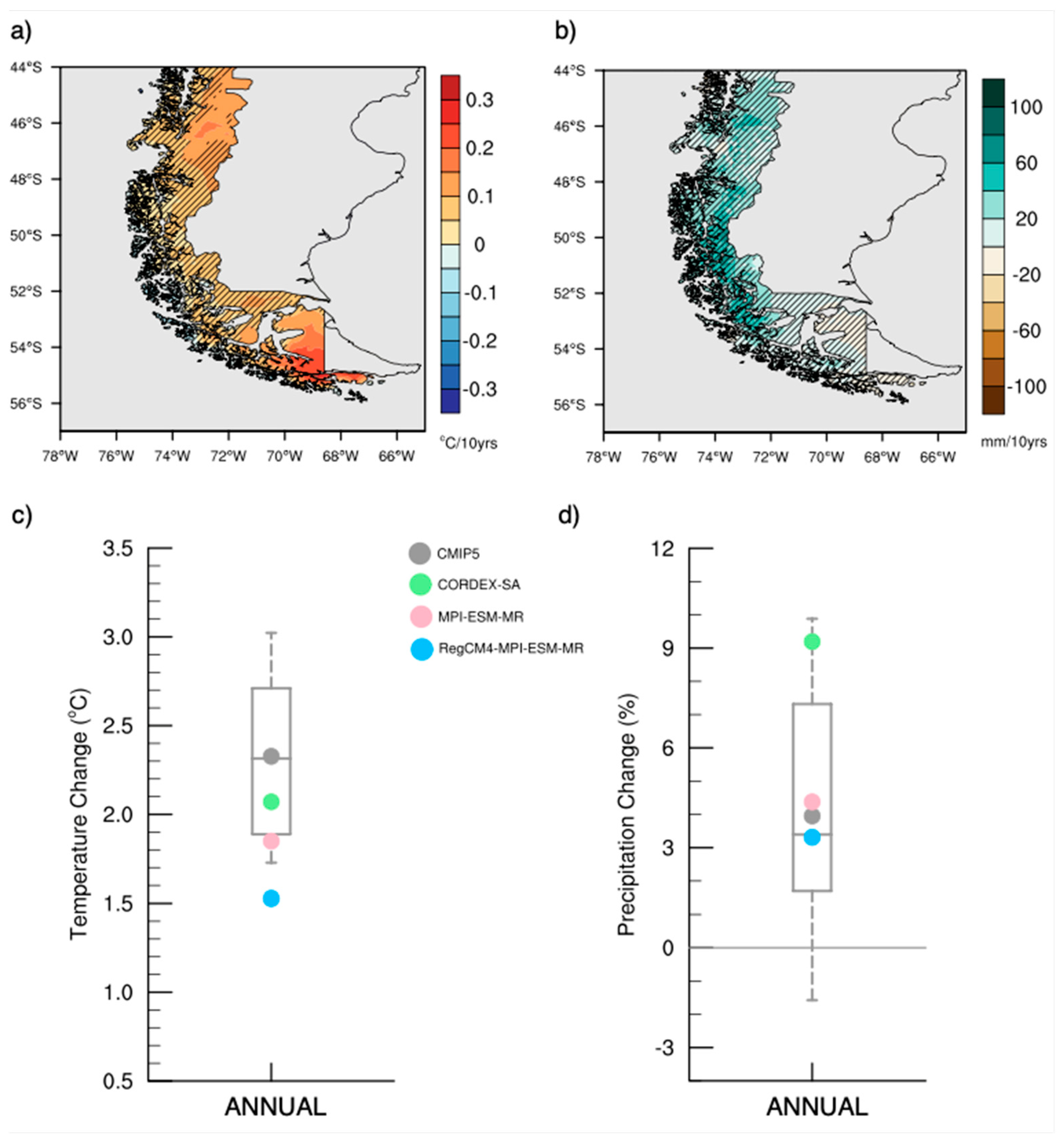

The climate of the Magallanes region (southern South America in the definition of the IPCC-AR6) features a maritime climate, with annual mean temperatures around 5–10 °C and about 5 °C differences between summer and winter (

Figure 1). It is characterized by year-round precipitation of about 500 mm, with a small annual cycle and relatively small interannual variability [

49]. The region is under the year-round influence of the southern westerly winds, with peak wind magnitudes during summer [

50]. Over the period 1979–2018, the region has seen positive temperature trends of the order of 0.1–0.2 °C per decade (

Figure 1a), which is statistically significant only in some parts of the region. In recent years, there has been a significant decline in the snow cover [

51], which is correlated with a statistically significant winter warming of Punta Arenas (0.71 °C, between 1972 and 2016). In most parts of the region, the data show small increasing precipitation trends (10 to 20 mm per decade), again, most of which are not statistically significant (

Figure 1b). Punta Arenas shows a non-significant increasing precipitation trend from 1960 to 2016 [

49], but precipitation has decreased over the last five years. There is also widespread glacier mass loss associated with the warming and snow decline along the Andes, including southern Patagonia [

52,

53]. Future projections indicate further warming, although slower than the global average and the rest of the country. CMIP5 and Cordex simulations project a slight increase in precipitation under a low and high greenhouse gas concentration scenario [

54].

Figure 1d shows, for the period 2070–2099, about a 5% precipitation increase compared with the 1976–2005 period, whereas the newer set of climate projections (CMIP6) indicates a slight drying.

When analyzing the direct greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and removals of Chile by region, Magallanes is within the group of carbon-negative regions due to the absorption influenced by the land-use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) sector (

Figure 2). In 2018, this region emitted 3332 kt CO

2 eq, representing 3.0% of the national total. Stationary energy was the main emitting sector (14%), which considers the burning of fuel for power generation for industries and commercial, public, and residential buildings. On the other hand, the LULUCF sector absorbed –10,752 kt CO

2 eq in 2018, representing 16.6% of the sector at the national level, mainly produced by the native forest [

55]. Although its GHG emissions are very low, its level of emissions per capita is among the highest in the country, which is mainly associated with an inefficient use of heating systems despite the larger need for energy due to the climatic conditions [

56].

Some studies [

3,

4,

57] have shown that in this region, the regional identity is stronger than in any other part of Chile. The most salient component of this identity is the way of inhabiting this territory, influenced by extreme climatic conditions and unique ecosystems that have shaped the local culture, forming a regional ecological identity [

4,

57]. Thus, for those born here or who have lived in this territory for a long time, climate change might challenge not only their traditional way of living but also the definition of who they are. For example, a less intense and shorter snow season already has multiple impacts on people´s lives, such as the opportunity of spending more time outside of their homes than they used to in the past. This also illustrates another important aspect of the problem, the possibility of perceiving positive impacts associated with climate change due to more favorable climatic conditions. However, these changes could also trigger negative emotional responses associated with grief or anxiety [

58,

59].

All in all, it is still unclear whether this regional ecological identity is translated into a greater sense of responsibility for protecting the local natural environment, or a more active role in dealing with climate change. In recent years, different calls for building a more sustainable city or a science-based urban development have emerged from other sectors to respond to these environmental challenges. On the contrary, the salmon industry is pushing for its expansion, and massive renewable energy initiatives related to wind and green hydrogen are being considered to steer the region’s development, with multiple social and environmental uncertainties about the benefits and risks these activities could have. As a result, many environmental organizations have been formed, especially in the last decade, to oppose mining- and energy-related projects and infrastructure developments, among others, that could have severe environmental impacts.

Dealing with this conundrum will demand stronger community participation to coordinate multiple stakeholders with different values towards a common goal aimed at the protection of all these areas, safekeeping the relevant ecosystem services that are provided on local, national, and global scales, and the wellbeing of the inhabitants of this region. Thus, knowing the importance of the environment for the local identity, the projected climate change scenarios, the proliferation of environmental organizations, the economic pressures, and a constitutional transition towards more participatory and decentralized institutions, how do people in Punta Arenas perceive these challenges and their role in them?