1. Introduction

There is no doubt that environmental issues are not only related to our health, but also to financial development and urbanization. However, some scholars have pointed out that the existing standards of environmental regulations are not sufficient to reduce environmental degradation [

1,

2,

3]. The current trend of natural environment degradation is becoming increasingly more obvious, which is of great concern [

4,

5]. Because of the demand for progressively stricter national environmental policies (e.g., public disclosure of enterprise environmental performance) and organizational stakeholders (e.g., employees, consumers and regulators), organizations across the world, in pursuit of sustainable development, are beginning to implement environmental policies and practices in their organizations [

6,

7]. The implementation of corporate green policies require the cooperation of employees, and employees’ workplace green behaviors (EWGBs), to a certain extent, affect corporate environmental initiatives [

8,

9]. However, the inertia of most organizational employees toward environmental issues has been hindering the advancement of corporate environmental strategies [

10]. In this context, exploration of the factors that influence employees’ pro-environmental behavior is of increasing interest to organizations and researchers [

9,

11,

12]. Organizations have begun to implement socially responsible policies and practices [

6], which require their employees to behave in “green” ways in the workplace [

8,

13]. A number of existing studies have documented that EWGBs not only contribute to organizational sustainability and the conservation of natural resources [

4,

6,

10], but also improve the environmental and financial performance of an organization [

14,

15,

16]. Thus, both scholars and practitioners have paid great attention to the factors that could give rise to these pro-social behaviors, among which environmentally specific servant leadership (ESSL) is considered to be an important enhancer [

10,

17].

Environmentally specific servant leadership is defined as “providing direction for, empowering and developing people to be pro-environmental citizens, and demonstrating humility, authenticity, interpersonal acceptance and stewardship towards employees’ pro-environmental contributions” [

12]. Robertson and Barling [

13] were the first to extend the concept of servant leadership, which focuses on facilitating followers’ well-being, development and success (e.g., [

18,

19]), to the environmental domain; then, an increasing number of studies began to examine the characteristics of ESSL and its impact on various employees’ outcomes. Environmentally specific servant leaders, who are regarded as a role model with green values, serve and help others, e.g., their subordinates, become devoted to achieving the green goals of their organizations and society [

17,

20]. Despite existing research on ESS leadership, an understanding of the mechanism explaining the relationship between ESS leadership and employees’ relevant behaviors, such as workplace green behaviors, remains lacking.

To fill this knowledge gap, this paper intends to empirically examine the relationship between ESS leadership and employee workplace green behaviors by utilizing a social learning perspective. According to social learning theory, individuals change their behaviors by imitating and learning the behaviors of role models [

21]. Employees’ perception of their leaders as role model plays an important role in their social learning process, and the existing research demonstrates that this perception can significantly influence their own ethical behaviors (e.g., [

22]). Some studies use social learning theory to explain why employees learn green behaviors from their leaders [

23], but these studies have not yet identified the mechanism that influences employees’ social learning from an ESS leader. ESS leaders strive to promote and foster green behaviors among employees through a series of green conducts, such as green empowerment, green value creation, providing assistance to followers regarding achieving environmental goals, putting the environment first, and ethical behavior toward the environment [

17], which are green role models for their subordinates, and subsequently strive to increase their EWGB. Moreover, employees’ perceived CSR moderates this relationship because employees would pick up on these signals and learn from those CSR-related organizational actions and policies and then engage in more EWGB.

Overall, by constructing a conceptual model and conducting an empirical study, we sought to contribute to the literature in the following three ways. First, this study identifies and examines employees’ perception of a green role model as a social learning mechanism linking ESSL to EWGB. By exploring the mediating effect of an employee’s perception of green role models on this relationship, this study deepens the understanding of the mechanisms that shape EWGB by adopting a social learning perspective. Second, based on scholars’ categorization of EWGB into in-role and extra-role green behaviors in previous studies, this paper explores the impact of ESSL on not only in-role but also extra-role green behaviors. Employees have varying degrees of discretion in their in-role and extra-role behaviors at the workplace [

24]; thus, the same factors may have distinct impacts on employee in-role and extra-role green behaviors [

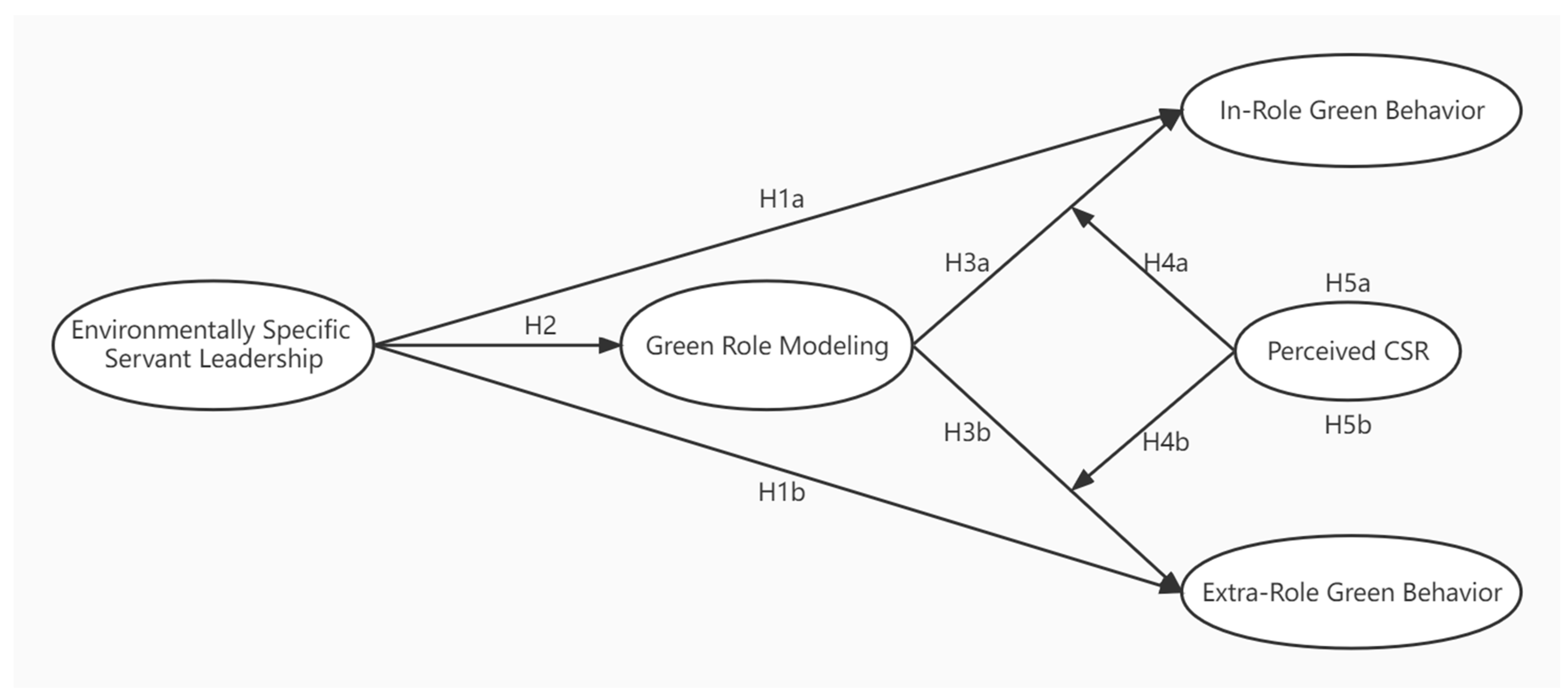

25]. Our study aims to investigate whether employees’ imitation of green role models affects employee in-role and extra-role green behaviors differently. Third, this study enriches the literature on ESSL and EWGB by clarifying when ESSL can be more effective at promoting EWGB. By integrating the mediating effects of an employee’s perceptions of green role models and the moderating effects of employees’ perceived CSR, this study provides a greater elucidation of how and under what conditions ESSL is more effective at promoting EWGB. Thus, our conceptual model is presented in

Figure 1.

Relying on the theoretical foundation provided by Bandura’s social learning theory, our primary research goal was to construct an integrated model by utilizing ESSL and CSR to explore the formation of employees’ workplace green behaviors. The specific objectives were to: (1) examine whether employees’ green behavior learning processes are consistent with the role model learning perspective proposed in Bandura’s social learning theory; (2) examine whether ESSL affects the extent to which employees view their leaders as green role models; (3) explore the moderating effect of CSR in the relationship between green role modeling and employee workplace in/extra-role green behavior. Different from previous studies, our study takes the four-step process of employee social learning as an entry point to investigate the mechanism of employees imitating the green behavior of their leaders. As a result, our study can provide a new research direction to examine EWGB and provide strategic advice to organizations on human resource management to foster green behaviors among employees and to better achieve their own sustainable development goals.

5. Discussion and Implications

Faced with growing environmental problems, organizations have started to implement green policies and to take actions for environmental protection and sustainable development [

68]. EWGB as an important factor in corporate sustainable development initiatives has received increasing attention from both scholars and practitioners [

9,

11,

12]. In this context, our research aims to explore how and when employees would emulate their leaders’ green behaviors. Based on the results of the empirical study, we found that employees imitate the pro-environmental behaviors of their leaders via role modeling; meanwhile, CSR plays a moderating role in this process. Our findings are specified as follows:

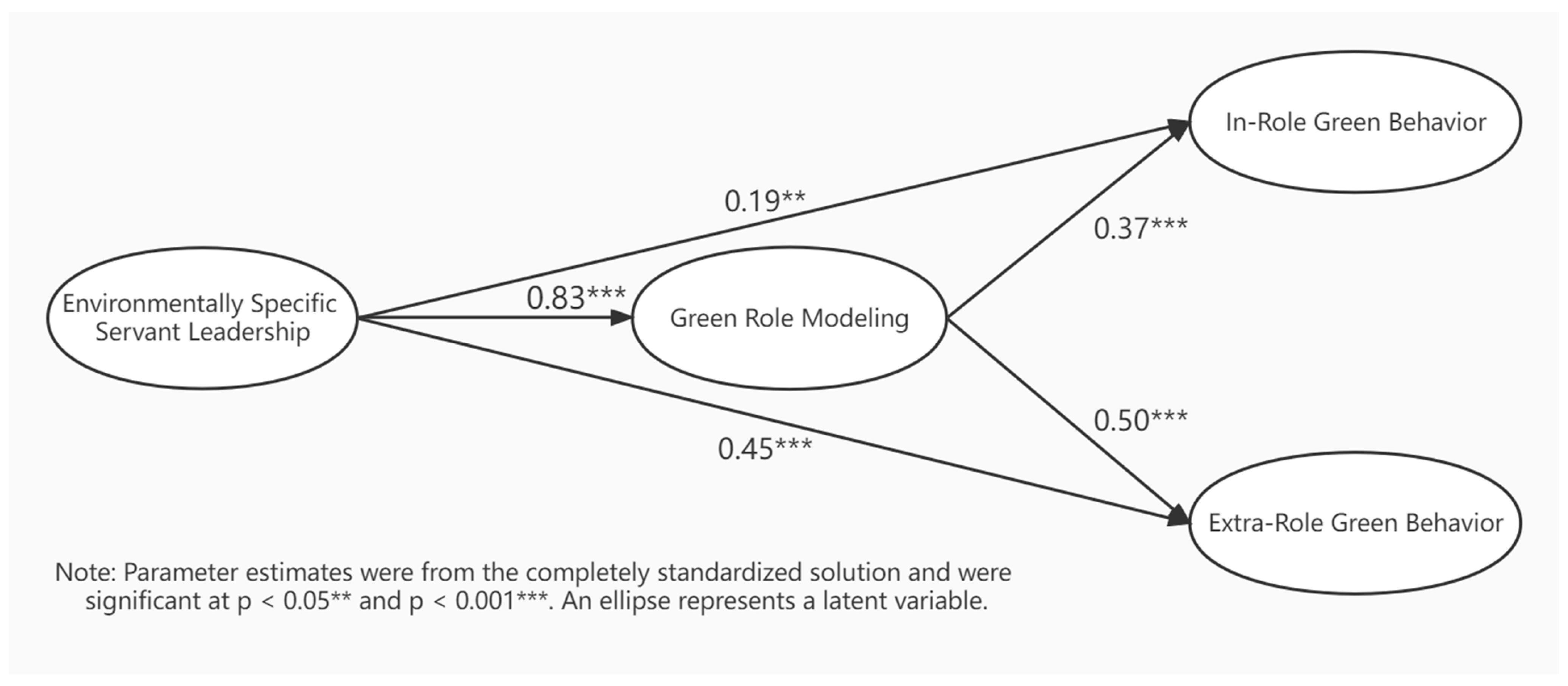

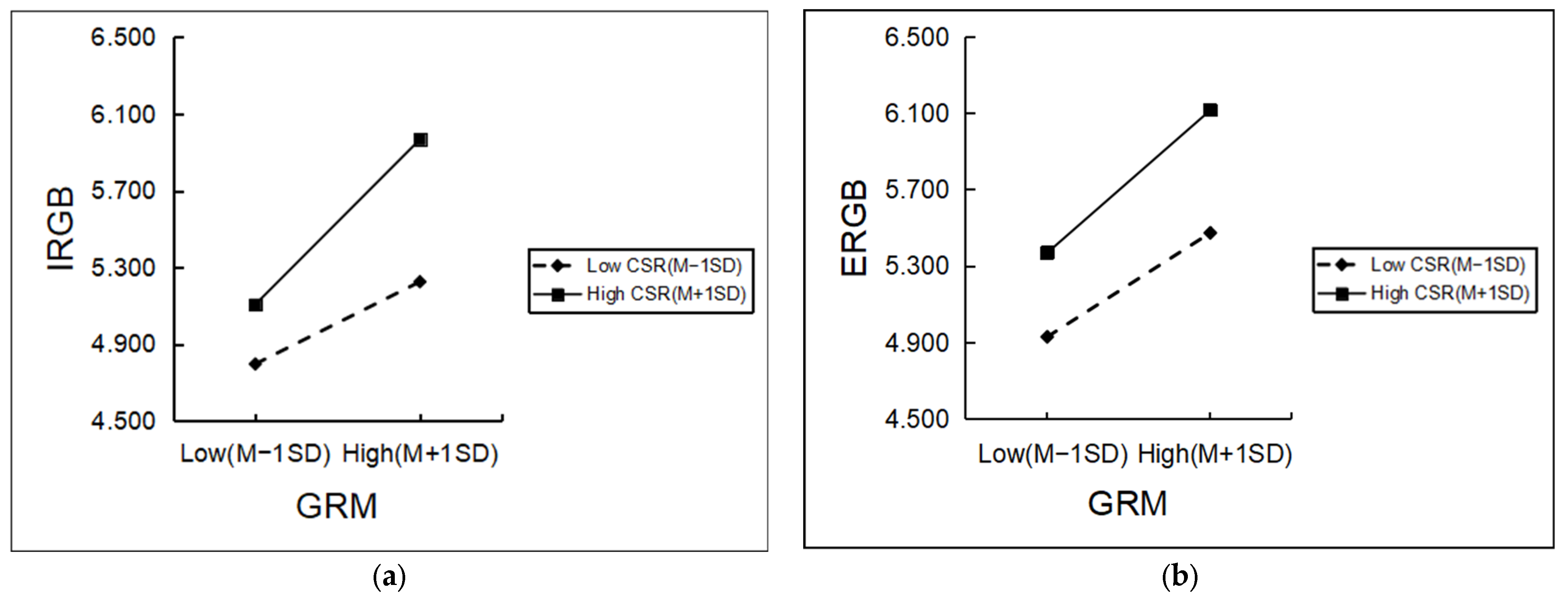

To begin, the finding that ESSL has a positive effect on both employee in-role and extra-role workplace green behaviors is consistent with that of previous literature [

6,

12,

17]. Moreover, our finding suggests that ESSL is indirectly related to both in-role and extra-role green behaviors through the mediation of employees’ perceived green role models. In other words, according to social learning theory, we suggest that the more leaders demonstrate ESSL, the more employees are likely to view them as green role models and to exert more in-role and extra-role green behaviors. Next, the finding suggests that employees’ perceived CSR moderates the mediating relationship between ESSL and EWGB through employees’ perceived green role models. Specifically, when employees perceive a high degree of perceived CSR, the mediated relationship between ESSL and EWGB through the perception of leaders as green role models was stronger. We believe that managers’ environmentally specific servant behaviors and organizational CSR policies and practices could promote employees’ workplace green behaviors, which contributes to the sustainability, environmental protection and societal development of society as a whole. The theoretical and practical implications of our findings are discussed below.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Through these findings, our study makes theoretical contributions to the growing body of research on green leadership and management in the following four ways.

First, as a response to Robertson and Barling’s [

13] call for research on environmentally specific servant leadership, the findings of our study expanded understanding of ESSL and confirmed the positive impact of ESSL on EWGB. A large number of studies in the existing literature focuses on the influence of leadership style on employee green behavior [

69,

70], but not enough attention has been paid to ESSL, a comparatively newly defined leadership style [

17]. Our study confirms that endeavors by an ESS leader who is willing to support and serve followers in green ways can increase employees’ green behaviors. Moreover, previous studies mainly examined the positive impact of environmentally specific servant leadership on employee extra-role green behaviors [

9,

71] rather than on employee in-role green behaviors. However, our study fully examined the positive impact of ESSL on both employee in-role and extra-role green behaviors to obtain a complete and comprehensive understanding of employee green behaviors. Servant leaders who are humble always make the development of others one of their goals at work [

28]. Thus, employees will have a much easier time accepting the work instructions from ESS leaders and behaving in a green way in the workplace. Our findings confirmed that ESSL not only positively influences an employee’s extra-role green behaviors, which echoes the findings of several studies in the literature, but also facilitates the employee’s in-role green behaviors as well.

Second, this study extends the current literature by demonstrating the mediating effect of employees’ perception of their leaders’ green role modeling on the relationship between ESSL and EWGB. Previous literature generally suggests that employees learn and imitate the green behaviors of their leaders through observational learning [

23]. Although a large number of studies have noticed this mechanism [

17,

71], empirical testing of this process is still lacking. In terms of a social learning perspective, our findings indicate that ESSL increases employees’ perceptions of their leaders as green role models and, consequently, increases their own in-role and extra-role green behaviors. Furthermore, the adoption of social learning theory will definitely enrich the theoretical boundaries of social learning theory and provide a comprehensive mechanism through which ESSL influences EWGB.

Third, drawing on social learning theory [

21], our research also contributes to EWGB research by exploring the boundary conditions in the indirect effect of ESSL on EWGB. As CSR is regarded as an effective strategy for achieving sustainability, a number of scholars have examined the role of CSR in their studies of employee green behavior [

9,

72]. Our study is the first to examine the moderating effect of employees’ perceived CSR in the ESSL literature. We provide a theoretical model and utilize empirical evidence to explain why employees’ CSR perceptions moderate the mediating relationship between ESSL and EWGB through green role modeling. We found that, for employees’ who perceive high levels of CSR, high scores on ESSL lead to a greater green role modeling effect, thus increasing employees’ green behaviors.

Fourth, the current study enhanced our understanding of ESSL and EWGB in the Chinese context. By drawing from theories regarding ESSL and EWGB developed in the Western context, we found that the results are consistent with what is expected in a Western context, which emphasizes the universal aspects of the relevant concepts and theories.

5.2. Practical Implications and Policy Suggestions

Green management is a contemporary global concern, and our study on ESSL in encouraging and motivating EWGB has important managerial implications. The findings of our model suggest that if enterprises wish to inspire green behaviors of their subordinates, an effective way is to actively take on corporate social responsibility and encourage leaders to act in a green manner so that they can serve as green role models by their subordinates.

More specifically, organizations should estimate, develop and reward ESS leadership behaviors. For instance, more attention should be paid to the recruitment and promotion process during which the organizations select potential leaders who exhibit ESS leadership. Moreover, the traits of ESS leadership could be added to the criteria for a performance appraisal system and a reward system for these leaders. For example, the organization could give extra bonuses to leaders who promote electricity conservation among their subordinates. In addition, we suggest that the HRM department consider providing relevant training programs to leaders for ESS leadership development. This suggestion regarding HRM practices can help leaders emphasize ESS leadership behaviors and act as green role models.

Furthermore, our research also points out that employees’ green behaviors are influenced by their perceptions of their leaders. Therefore, organizations should pay equal attention to leaders and subordinates during the implementation of green policies. For example, in training process, organizations should encourage subordinates to discover the good qualities of their leaders and regard them as green role models, which can help to facilitate the social learning process of their employees.

Finally, as the results of model testing indicated, a high level of perceived CSR can promote employee workplace in-role and extra-role green behaviors because the employees can learn directly from organizational CSR values and actions. Therefore, we believe that organizational CSR practices can help create a pro-social and pro-environmental atmosphere and climate within the organization. These CSR practices, which are beneficial for individual and team development, trigger leaders to exhibit servant behaviors toward environmental goals. Thus, it is essential for organizations to adopt CSR practices to create a “green” climate to motivate not only the leaders but also the employees. In summary, organizations should adopt specific HRM practices and CSR behaviors to increase the “green” climate to increase employees’ green behaviors.

Based on the results of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed: The government should encourage enterprises to adopt CSR behaviors, implement relevant management practices and engage in environmentally friendly activities. On the one hand, we suggest that the Chinese government should target distinct policy arrangements toward enterprises with different types of ownership. First, it is important to develop a supervision mechanism to monitor the CSR-related or environmental behaviors of state-owned enterprises, e.g., whether the enterprise publishes proper annual CSR reports or whether the enterprise has an environmental policy and behaves in an environmentally friendly way. Second, the government could motivate non-state-owned enterprises to play an important role in CSR implementation and environmental protection. On the other hand, the central government should establish a proper performance evaluation mechanism with both financial and non-financial performance standards, e.g., environmental standards for local governments. Meanwhile, the government could appeal to relevant non-governmental or non-profit organizations to participate in monitoring enterprises’ green behaviors.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the fact that this study makes theoretical contributions to the literature and practical implications to practitioners, it still has some limitations that should be noted. First, all the variables in our study were self-reported by employees in the data collection process, which perhaps leads to common method bias. Although common method bias was avoided to some extent in our study due to the two-wave time-lag design [

57], common method bias cannot be completely eliminated. Therefore, we suggest that future studies could select data from multiple sources for their studies, such as supervisors being invited to rate employees’ green behaviors. Moreover, the adoption of employee self-reports for data collection may suffer from a lack of objectivity. Although a meta-analysis pointed out that self-reported data are correlated with actual data in terms of green behavior [

73], we recommend scholars utilize more objective data for future studies to validate the study. Second, this study considers employees’ perceived green role model of leadership as mediating factors. However, from the perspective of social learning theory [

21], we believe that other factors also affect the learning effectiveness of employees. Thus, we suggest that future studies consider other factors at the organizational, team and individual levels as mediating factors for the study. Third, our study only considered CSR as a boundary condition that influences the social learning process of employees’ green behaviors. We believe that more variables have an impact on the social learning process of employees, and future studies can consider variables such as organizational identity, individual green values, and green self-efficacy. Fourth, we have only tested our theory in the Chinese context, and future studies may consider extending our theory to different cultural contexts for validation.