Understanding the Determinants and Motivations for Collaborative Consumption in Laundromats

Abstract

:1. Introduction

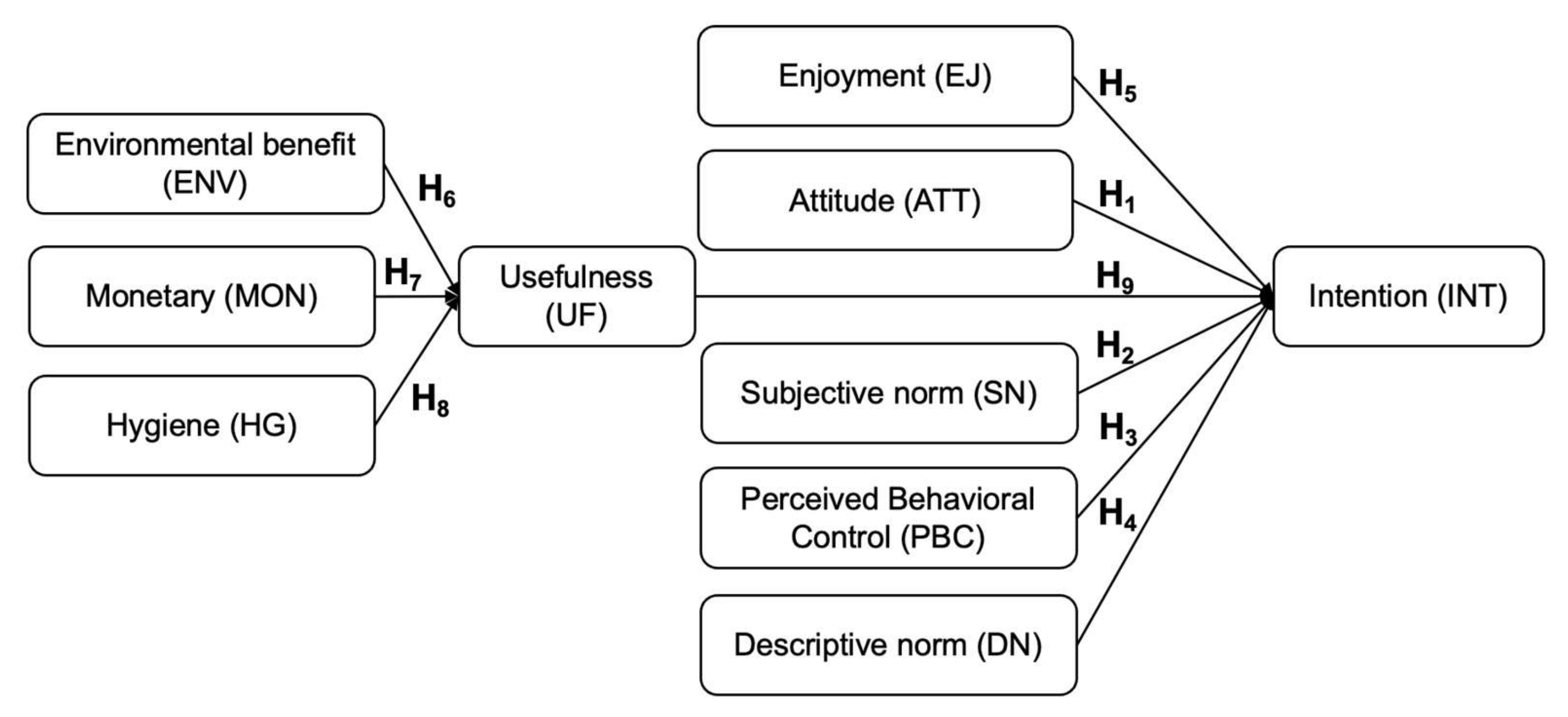

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Study Area and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

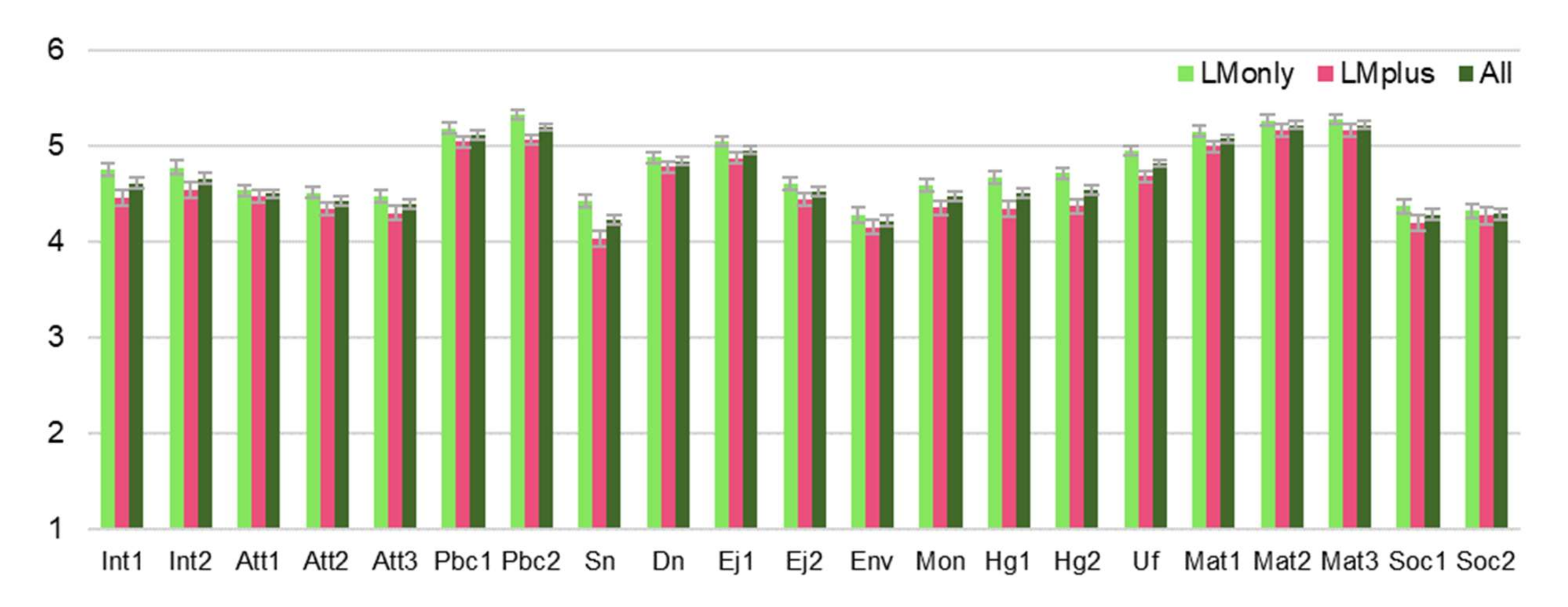

4.1. Analysis of the Measurement Variables

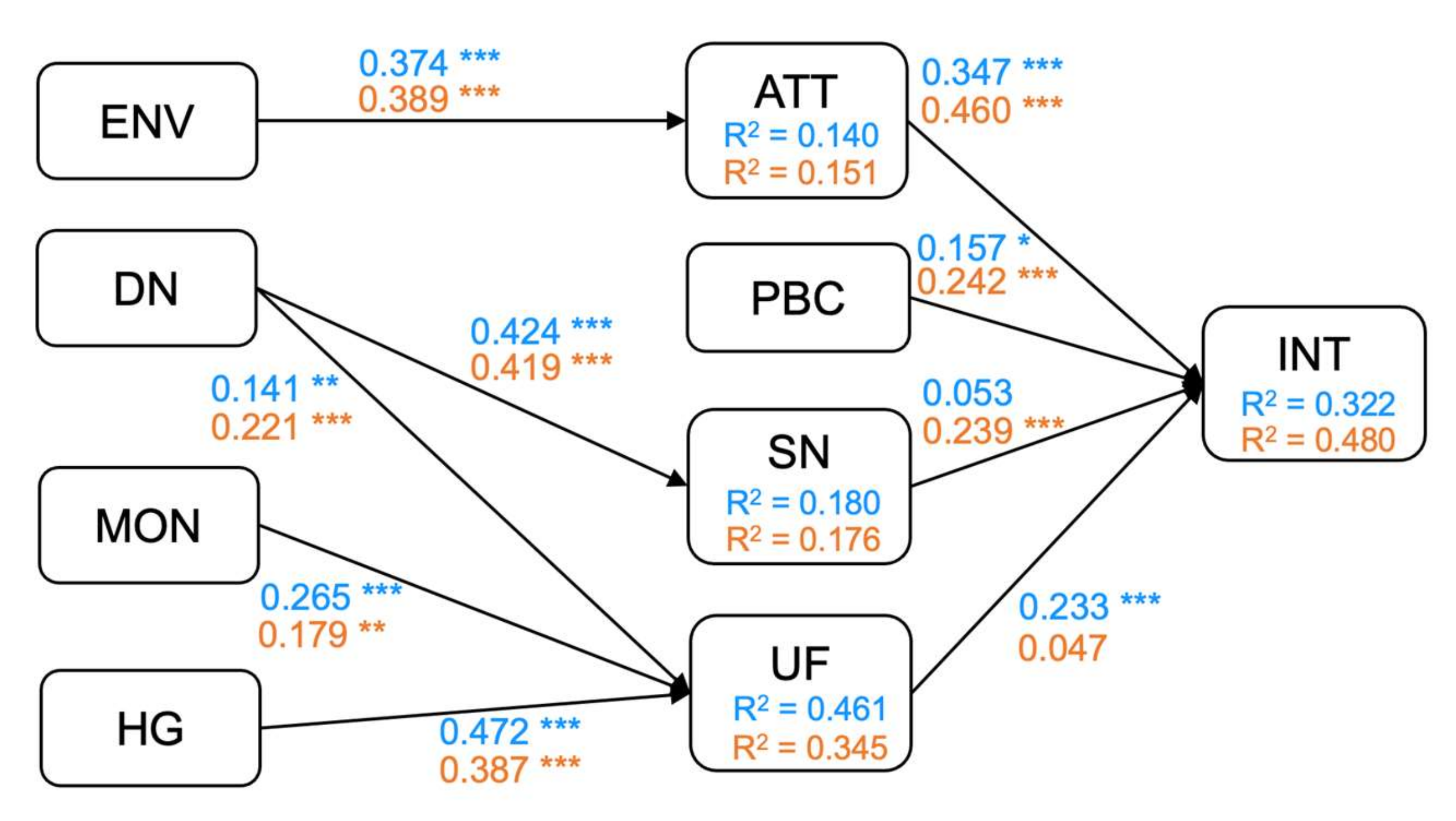

4.2. Model Evaluation

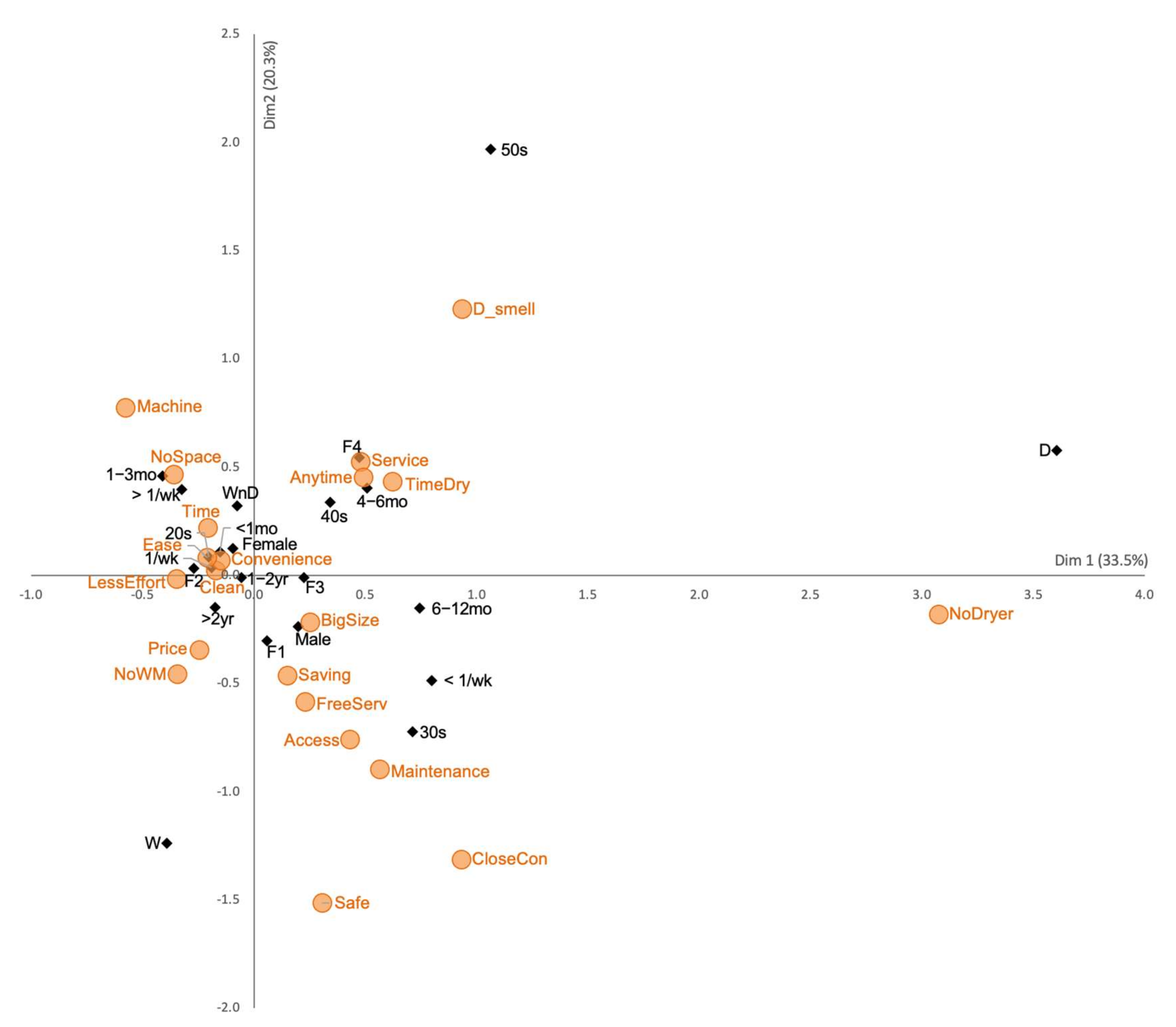

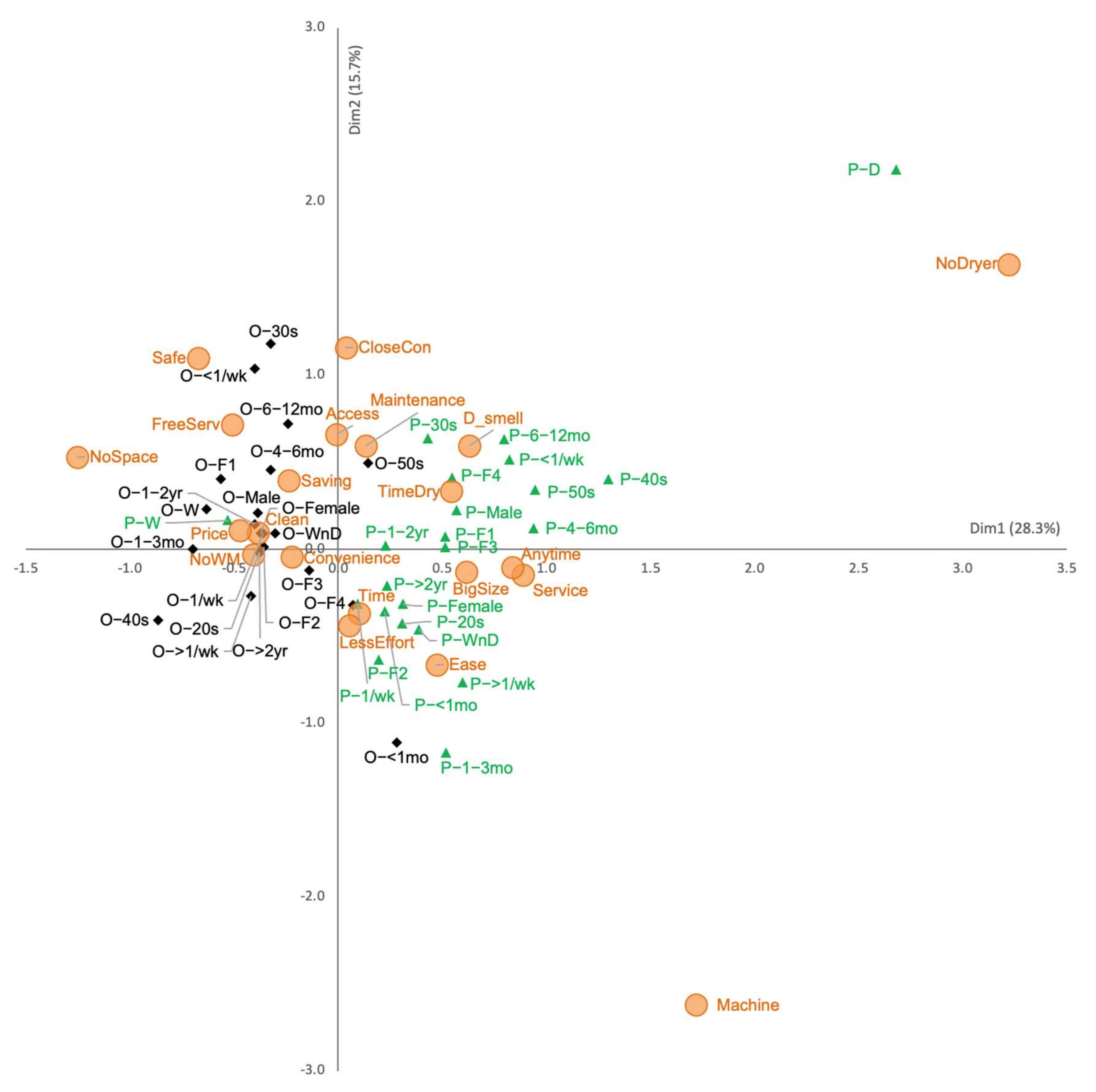

4.3. Correspondence Map of Reasons for LM Use

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

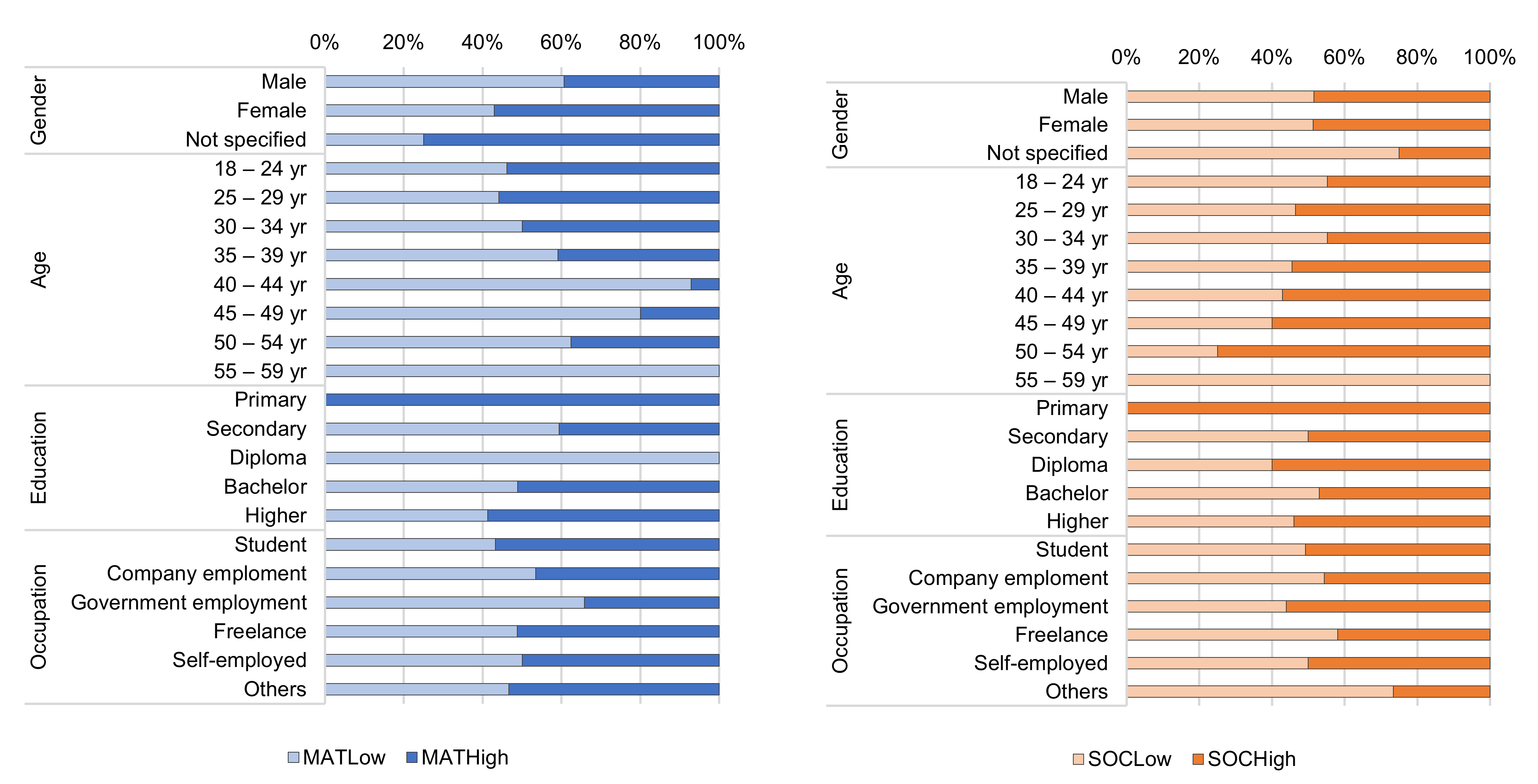

| Items | Category | All | LMonly | LMplus a | Difference between LMonly and LMplus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | 469 | 239 | 230 | ||

| Gender | Male | 35.2% | 34.7% | 35.7% | Chi-square = 0.006, df = 1, p = 0.94 |

| Female | 64.0% | 63.6% | 64.3% | ||

| Not specified | 0.9% | 1.7% | 0.0% | ||

| Age | 18–24 yr | 49.5% | 54.8% | 43.9% | Mann–Whitney U = 23,055.5, p = 0.001 |

| 25–29 yr | 27.1% | 28.9% | 25.2% | ||

| 30–34 yr | 12.4% | 9.2% | 15.7% | ||

| 35–39 yr | 4.7% | 3.3% | 6.1% | ||

| 40–44 yr | 3.0% | 2.1% | 3.9% | ||

| 45–49 yr | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.3% | ||

| 50–54 yr | 1.7% | 0.4% | 3.0% | ||

| 55–59 yr | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.9% | ||

| Education level | Primary | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.4% | Chi-square = 0.066, df = 2, p = 0.968 |

| Secondary | 6.8% | 6.7% | 7.0% | ||

| Diploma | 1.1% | 1.3% | 0.9% | ||

| Bachelor | 78.5% | 78.2% | 78.7% | ||

| Higher | 13.4% | 13.8% | 13.0% | ||

| Family size | 1 person | 32.0% | 38.1% | 25.7% | Mann–Whitney U = 20,872.5, p < 0.001 |

| 2 people | 40.5% | 45.2% | 35.7% | ||

| 3 people | 10.7% | 6.7% | 14.8% | ||

| >4 people | 16.8% | 10.0% | 23.9% | ||

| Occupation | Company employee | 21.5% | 24.7% | 18.3% | Chi-square = 23.016, df = 5, p < 0.001 |

| Government employee | 8.7% | 7.1% | 10.4% | ||

| Self-employed | 14.9% | 9.6% | 20.4% | ||

| Freelance | 9.2% | 8.8% | 9.6% | ||

| Student | 42.4% | 48.5% | 36.1% | ||

| Others | 3.2% | 1.3% | 5.2% | ||

| House type | Condo/Apartment | 16.8% | 18.8% | 14.8% | Chi-square = 49.721, df = 2, p < 0.001 |

| Detached house | 24.5% | 10.9% | 38.7% | ||

| Room rental | 57.4% | 69.0% | 45.2% | ||

| Tenement | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.3% | ||

| Others | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.0% | ||

| Experience of LM use | <1 month | 7.9% | 2.1% | 13.9% | Mann–Whitney U = 21,433.5, p < 0.001 |

| 1–3 months | 9.0% | 7.5% | 10.4% | ||

| 4–6 months | 8.1% | 7.1% | 9.1% | ||

| 6 months–1 year | 12.2% | 10.9% | 13.5% | ||

| 1–2 years | 24.1% | 28.0% | 20.0% | ||

| >2 years | 38.8% | 44.4% | 33.0% | ||

| Frequency of LM use | ≥4 times per week | 1.3% | 0.8% | 1.7% | Mann–Whitney U = 20,613, p < 0.001 |

| 2–3 times per week | 23.5% | 30.5% | 16.1% | ||

| 1 time per week | 53.9% | 56.1% | 51.7% | ||

| every 2 weeks | 15.8% | 12.1% | 19.6% | ||

| every 3 weeks | 1.1% | 0.4% | 1.7% | ||

| Occasional | 4.5% | 0.0% | 9.1% | ||

| Service use at LM | Wash and dry | 74.0% | 77.0% | 70.9% | Chi-square = 23.987, df = 2, p < 0.001 |

| Wash only | 20.7% | 21.8% | 19.6% | ||

| Dry only | 5.3% | 1.3% | 9.6% | ||

| Expenses | THB per wash | 44.6 | 41.3 | 48.5 | Mann–Whitney U = 21,213.5, p = 0.014 |

| THB per dry | 42.8 | 41.2 | 44.5 | Mann–Whitney U = 15,025.5, p = 0.001 | |

| Factor | Item | Std Loading a | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention (INT) | Int1 Int2 | 0.96 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.90 |

| Attitude (ATT) | Att1 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.74 |

| Att2 | 0.88 | ||||

| Att3 | 0.85 | ||||

| PBC | Pbc1 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.65 |

| Pbc2 | 0.72 | ||||

| Hygiene (HG) | Hg1 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.74 |

| Hg2 | 0.90 | ||||

| Criteria | ≥0.5 | ≥0.7 | ≥0.7 | ≥0.5 |

| Construct | INT | ATT | PBC | HG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | 0.95 | |||

| ATT | 0.53 | 0.86 | ||

| PBC | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.80 | |

| HG | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.86 |

| Indicator | Criteria | Overall | Group Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-squared/df | ≤5 | 3.806 | 2.744 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.077 | 0.061 |

| GFI | >0.80 | 0.940 | 0.919 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.958 | 0.948 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.945 | 0.922 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.932 | 0.915 |

| PNFI | >0.50 | 0.581 | 0.567 |

| PCFI | >0.50 | 0.590 | 0.583 |

References

- Heiskanen, E.; Jalas, M. Can services lead to radical eco-efficiency improvements? A review of the debate and evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2003, 10, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Eight types of product–service system: Eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-Based Consumption: The Case of Car Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, J. The Age of Access: The New Culture of Hypercapitalism, Where All of Life Is a Paid-For Experience; Author Putnam Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gullstrand Edbring, E.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: Motivations and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, T.; Riedelsheimer, T.; Gogineni, S.; Klemichen, A.; Stark, R. Systematic Literature Review—Effects of PSS on Sustainability Based on Use Case Assessments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.J.; van Halen, J.G.; te Riele, H.; Rommens, P.J.M. Product Service Systems, Ecological and Economic Basics; Ministry of Environment: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1999.

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, P. The Evolution of Social Commerce: The People, Management, Technology, and Information Dimensions. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 31, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Basu, M.; Saito, O. What and how are we sharing? A systematic review of the sharing paradigm and practices. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurisu, K.; Ikeuchi, R.; Nakatani, J.; Moriguchi, Y. Consumers’ motivations and barriers concerning various sharing services. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 308, 127269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C.; Lutz, C. What’s mine is yours (for a nominal fee)—Exploring the spectrum of utilitarian to altruistic motives for Internet-mediated sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S.J.; Gleim, M.R.; Perren, R.; Hwang, J. Freedom from ownership: An exploration of access-based consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.; Mattsson, J. Understanding collaborative consumption: Test of a theoretical model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 118, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wen, H. How Is Motivation Generated in Collaborative Consumption: Mediation Effect in Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, M. Collaborative consumption practices in Southeast Asian cities: Prospects for growth and sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Mugge, R.; Bom, C.A.; Lemstra, H.-J. Pay-per-use business models as a driver for sustainable consumption: Evidence from the case of HOMIE. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigüenza, C.P.; Cucurachi, S.; Tukker, A. Circular business models of washing machines in the Netherlands: Material and climate change implications toward 2050. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasawa, E.; Suzuki, Y.; Moon, D.; Nakatani, J.; Sugiyama, H.; Hirao, M. Designing Interventions for Behavioral Shifts toward Product Sharing: The Case of Laundry Activities in Japan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klint, E.; Peters, G. Sharing is caring-the importance of capital goods when assessing environmental impacts from private and shared laundry systems in Sweden. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laundrycity. The History of Laundromat. 2020. Available online: https://www.sudzmoundlaundry.com/the-history-of-laundromat/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Jitpleecheep, P. Clean as a Whistle. 2019. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1712596/clean-as-a-whistle/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Rungfapaisarn, K. Maru Laundry Takes Coin-Operated Laundry Machines into New Era. 2019. Available online: https://www.nationthailand.com/business/30372839/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Department of Business Development. Twelve Business Trends for 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.dbd.go.th/news_view.php?nid=469419433/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Retamal, M.; Schandl, H. Dirty Laundry in Manila: Comparing Resource Consumption Practices for Individual and Shared Laundering. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 22, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.; Amasawa, E.; Hirao, M. Laundry Habits in Bangkok: Use Patterns of Products and Services. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, B. Do environmental concern and perceived risk contribute to consumers’ intention toward buying remanufactured products? An empirical study from China. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.K.; Mun, J.M.; Chae, Y. Antecedents to internet use to collaboratively consume apparel. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 20, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Lunardo, R.; Benoit-Moreau, F. Sustainability of the sharing economy in question: When second-hand peer-to-peer platforms stimulate indulgent consumption. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Materialism: Trait Aspects of Living in the Material World. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, S.S.; Baker, S.M. An integrative review of material possession attachment. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2004, 1, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chiangmai Provincial Public Health Office. Population in Chiang Mai 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.chiangmaihealth.go.th/cmpho_web/detail_article2.php?info_id=670/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Millsap, R. Using the Bollen-Stine Bootstrapping Method for Evaluating Approximate Fit Indices. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2014, 49, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevitt, J.; Hancock, G. Performance of Bootstrapping Approaches to Model Test Statistics and Parameter Standard Error Estimation in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2001, 8, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doey, L.; Kurta, J. Correspondence Analysis applied to psychological research. Tutorials Quant. Methods Psychol. 2011, 7, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, D.; Antoniou, C.; Waddell, P. Factors affecting the adoption of vehicle sharing systems by young drivers. Transp. Policy 2013, 29, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, P.; Mai, R.; Hoffmann, S. When do materialistic consumers join commercial sharing systems. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4215–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bound, J.; Brown, C.; Mathiowetz, N. Measurement Error in Survey Data. In Handbook of Econometrics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 5, pp. 3705–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Item | Questionnaire Statement | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention (INT) | Int1 | I want to use LMs in the future. | [15]; [17] |

| Int2 | I expect to continue using LMs in the future. | ||

| Attitudes (ATT) | Att1 | Sharing goods and services are a positive thing. | [15] |

| Att2 | Sharing or CC is a better mode of consumption than selling and buying individually. | ||

| Att3 | I find participating in CC of goods and services such as using LM is a good move. | ||

| PBC | Pbc1 | LMs are flexible, I can do laundry anytime. | [31] |

| Pbc2 | Using LMs is easy. | ||

| Subjective norm (SN) | Sn | My family or people close to me encourage me to use LMs. | [17] |

| Descriptive norm (DN) | Dn | Other people use LMs. * | |

| Enjoyment (EJ) | Ej1 | Using LMs is pleasant. | [17] |

| Ej2 | I enjoy using LMs. | ||

| Environmental benefits (ENV) | Env | Using LMs is a sustainable consumption choice. | [15] |

| Monetary benefits (MON) | Mon | Using LMs is worth the money. | [17] |

| Hygiene (HG) | Hg1 | Using LMs is clean. * | |

| Hg2 | Using LMs is hygienically safe. * | ||

| Usefulness (UF) | Uf | The advantages of LMs outweigh the disadvantages. | [17] |

| Materialism (MAT) | Mat1 | I would be happier if I could afford to buy more things. | [14], [36] |

| Mat2 | I want to be rich enough to buy anything I want. | ||

| Mat3 | I would rather buy something I need than borrow or rent it. | ||

| Sociability (SOC) | Soc1 | I prefer working with others rather than being alone. | [14] |

| Soc2 | I love to be with people. |

| Items | Standardized Effects on INT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 469) | Group Analysis (n = 469) | ||||||||

| LMonly (n = 239) | LMplus (n = 230) | ||||||||

| Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| ATT | 0.41 *** | - | 0.41 *** | 0.35 *** | - | 0.35 *** | 0.46 *** | - | 0.46 *** |

| PBC | 0.19 *** | - | 0.19 *** | 0.16 * | - | 0.16 * | 0.24 *** | - | 0.24 *** |

| SN | 0.16 *** | - | 0.16 *** | 0.05 | - | 0.05 | 0.24 *** | - | 0.24 *** |

| DN | - | 0.09 *** | 0.09 *** | - | 0.06 | 0.06 | - | 0.11 *** | 0.11 *** |

| ENV | - | 0.16 *** | 0.16 *** | - | 0.13 *** | 0.13 *** | - | 0.18 *** | 0.18 *** |

| MON | - | 0.03 *** | 0.03 *** | - | 0.06 *** | 0.06 *** | - | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| HG | - | 0.06 *** | 0.06 *** | - | 0.11 *** | 0.11 *** | - | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| UF | 0.14 *** | - | 0.14 *** | 0.23 *** | - | 0.23 *** | 0.05 | - | 0.05 |

| Path | Overall (n = 469) | LMonly (n = 239) | LMplus (n = 230) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE 1 | p | Effect | SE 1 | p | Effect | SE 1 | p | |

| via attitude | |||||||||

| ENV → ATT → INT | 0.148 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.113 | 0.045 | 0.001 | 0.184 | 0.057 | 0.001 |

| via subjective norms | |||||||||

| DN → SN → INT | 0.100 | 0.038 | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.038 | 0.510 | 0.131 | 0.046 | 0.002 |

| via usefulness | |||||||||

| DN → UF → INT | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.039 | 0.021 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.358 |

| MON → UF → INT | 0.033 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.066 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.306 |

| HG → UF → INT | 0.067 | 0.027 | 0.007 | 0.137 | 0.053 | 0.004 | 0.019 | 0.029 | 0.434 |

| Category | No. | Label | Reason | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessity | (1) | NoSpace | No space for washing machine/drying | 6 |

| (2) | NoDryer | No dryer | 8 | |

| (3) | NoWM | No washing machine | 50 | |

| Quality of LM service | (4) | Safe | Feeling LM as safe place to use | 6 |

| (5) | Machine | Good quality of machines | 3 | |

| (6) | BigSize | Availability of big loading size | 15 | |

| (7) | Clean | Cleanliness | 85 | |

| (8) | D_smell | Dryer use to avoid unpleasant smell | 10 | |

| (9) | Service | Extra laundry services (i.e., folding and service staff) | 12 | |

| (10) | FreeServ | Other free services (i.e., Wi-Fi and waiting area) | 17 | |

| Money-saving | (11) | Price | Affordable price | 55 |

| (12) | Saving | Saving on products and utilities used at home (i.e., detergent, water, and electricity) | 14 | |

| Time-saving | (13) | Time | Time-saving/speed | 158 |

| (14) | TimeDry | Time-saving to use dryer | 93 | |

| Convenience | (15) | Access | Good access from living places | 57 |

| (16) | Maintenance | Unnecessity of maintenance | 8 | |

| (17) | Convenience | Convenience | 295 | |

| (18) | Anytime | Usage at anytime | 13 | |

| (19) | LessEffort | Less efforts for laundry | 32 | |

| (20) | Ease | Easy to use | 66 | |

| (21) | CloseCon | Good access to convenience stores | 6 | |

| Total count | 1009 | |||

| Category | Sub-Category | Label | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM usage condition | (a) Service use at LM | (a-1) | W | Wash only |

| (a-2) | D | Dry only | ||

| (a-3) | WnD | Wash and dry | ||

| (b) Experience of LM use | (b-1) | <1 month | <1 month | |

| (b-2) | 1–3 month | 1–3 months | ||

| (b-3) | 4–6 month | 4–6 months | ||

| (b-4) | 6–12 month | 6 months–1 year | ||

| (b-5) | 1–2 years | 1–2 years | ||

| (b-6) | >2 years | >2 years | ||

| (c) Frequency of LM use | (c-1) | <1/week | <1 time per week | |

| (c-2) | 1/week | 1 time per week | ||

| (c-3) | >1/week | >1 time per week | ||

| Socio-demographics | (d) Age | (d-1) | 20 s | 18–29 years old |

| (d-2) | 30 s | 30–39 years old | ||

| (d-3) | 40 s | 40–49 years old | ||

| (d-4) | 50 s | 50–59 years old | ||

| (e) Gender | (e-1) | Female | female | |

| (e-2) | Male | male | ||

| (f) Family size | (f-1) | F1 | 1 | |

| (f-2) | F2 | 2 | ||

| (f-3) | F3 | 3 | ||

| (f-4) | F4 | more than 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phuphisith, S.; Kurisu, K. Understanding the Determinants and Motivations for Collaborative Consumption in Laundromats. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911850

Phuphisith S, Kurisu K. Understanding the Determinants and Motivations for Collaborative Consumption in Laundromats. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911850

Chicago/Turabian StylePhuphisith, Sarunnoud, and Kiyo Kurisu. 2022. "Understanding the Determinants and Motivations for Collaborative Consumption in Laundromats" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911850

APA StylePhuphisith, S., & Kurisu, K. (2022). Understanding the Determinants and Motivations for Collaborative Consumption in Laundromats. Sustainability, 14(19), 11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911850