Agriculture from Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints (ANCs) in Poland, Its Characteristics, Directions of Changes and Challenges in the Context of the European Green Deal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Distribution of ANCs by Communes in Poland

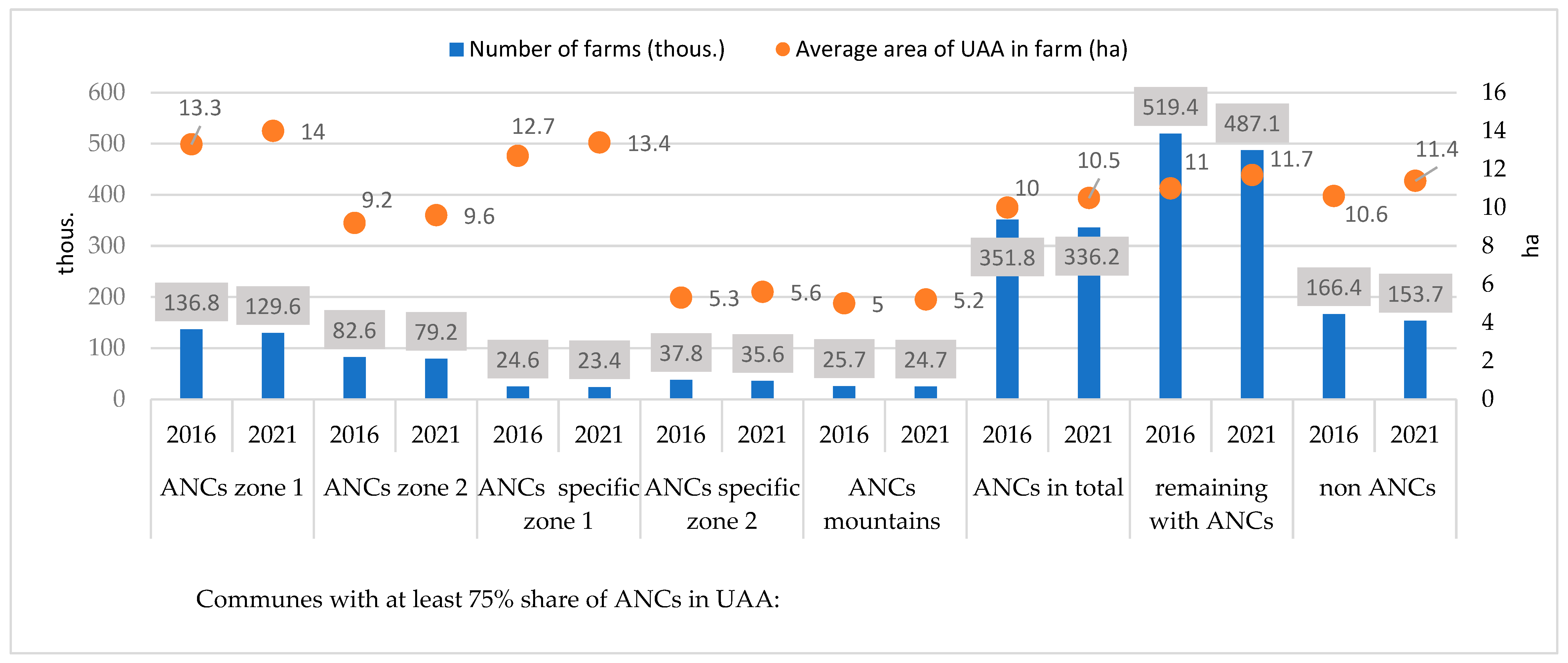

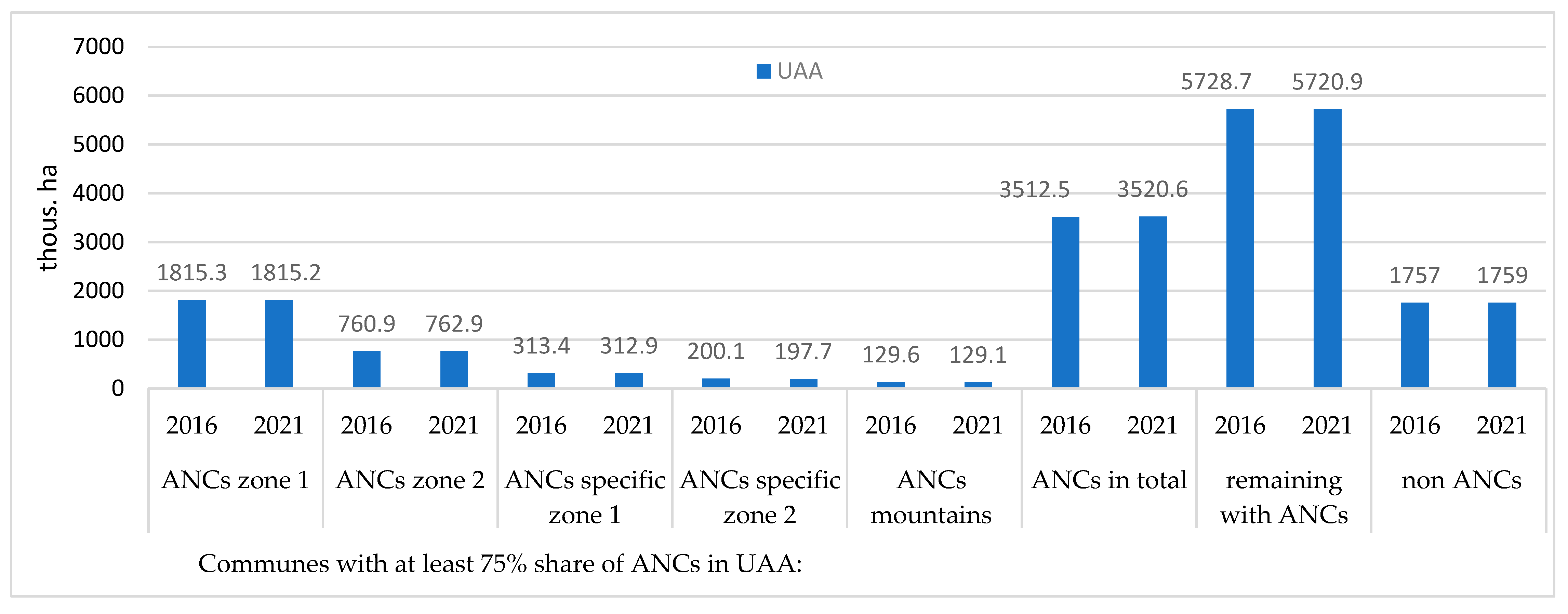

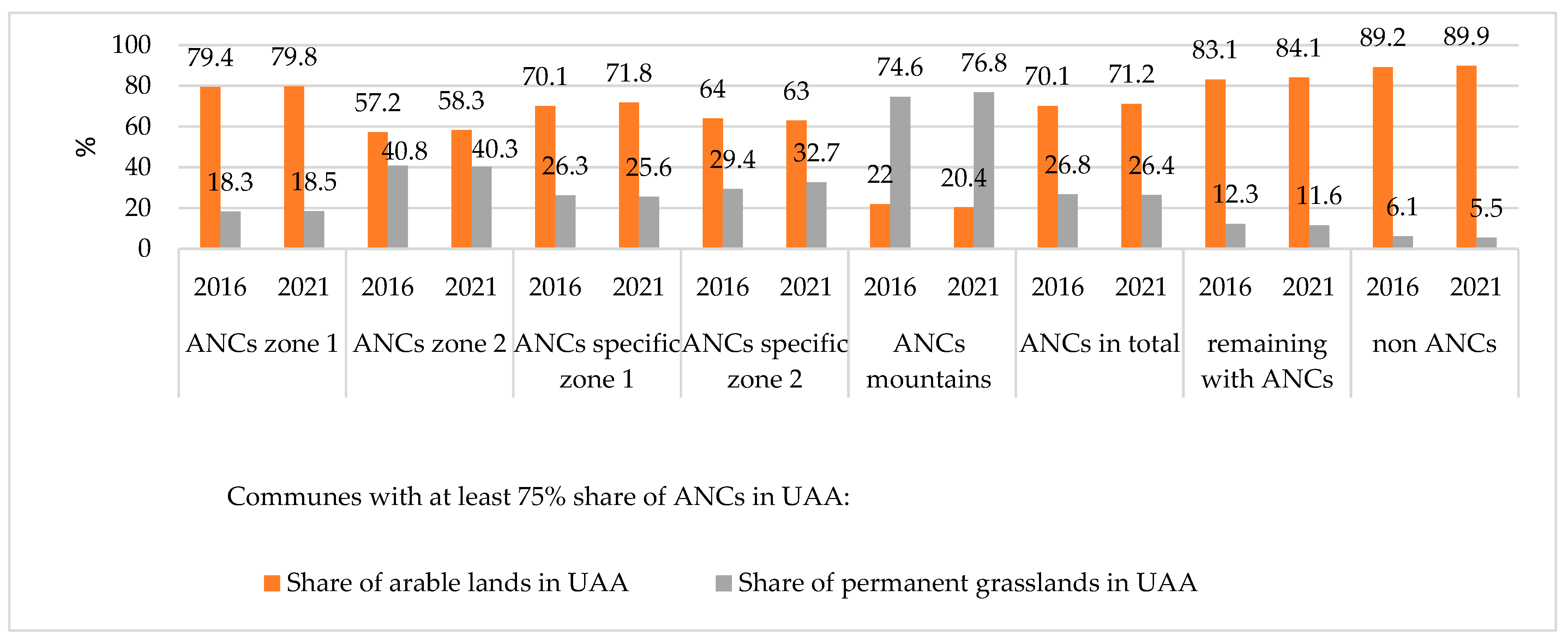

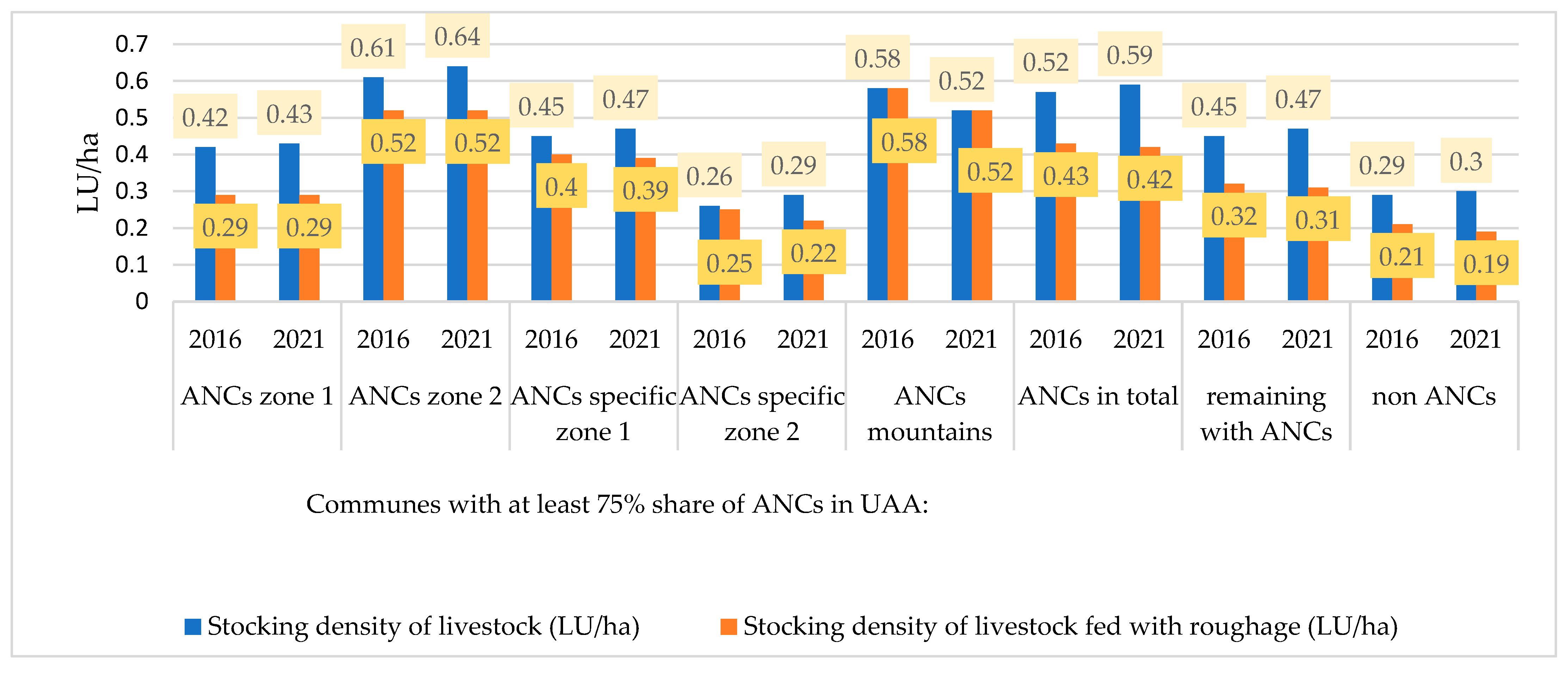

4.2. Features of Agriculture in Communes with a Particularly High Saturation of ANCs, as Compared to Other Communes in Poland

4.3. Economic Situation of Farms from ANCs Compared to Other Farms in the EU-27

4.4. Economic Situation of Farms from ANCs Compared to Other Farms in Poland

| Variable | Farms from ANCs: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Dairy Cows: | Mixed: | |||||

| Up to 25 Thous. Euro SO | (25–50 > Thous. Euro SO | Over 50 Thous. Euro SO | Up to 25 Thous. Euro SO | (25–50 > Thous. Euro SO | Over 50 Thous. Euro SO | |

| Number of farms | 187 | 490 | 792 | 711 | 406 | 402 |

| Total costs (euro/ha) | 1106.5 | 1329.9 | 1779.6 | 1072.2 | 1230.1 | 1449.3 |

| Direct costs (euro/ha) | 458.1 | 649.1 | 950.7 | 486.1 | 655.1 | 872.0 |

| Land productivity (euro/ha) | 1280.3 | 1780.1 | 2565.5 | 1082.2 | 1312.7 | 1657.9 |

| Labor productivity (euro thousand /AWU) | 9.4 | 20.5 | 51.0 | 9.4 | 20.3 | 45.3 |

| Income (euro/ha) | 545.8 | 866.9 | 1167.4 | 335.2 | 453.2 | 573.4 |

| Income less subsidies (euro/ha) | 137.0 | 439.6 | 797.5 | −40.0 | 66.9 | 211.3 |

| Income (euro thousands/FWU) | 4.1 | 10.1 | 24.6 | 3.2 | 7.1 | 17.2 |

| Net investment rate (%) | −57.3 | −12.4 | 73.4 | −24.4 | −7.5 | 17.0 |

| Variable | Farms without ANCs: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Dairy Cows: | Mixed: | |||||

| Up to 25 Thous. Euro SO | (25–50 > Thous. Euro SO | Over 50 Thous. Euro SO | Up to 25 Thous. Euro SO | (25–50 > Thous. Euro SO | Over 50 Thous. Euro SO | |

| Number of farms | 57 | 154 | 235 | 298 | 295 | 337 |

| Total costs (euro/ha) | 1162.5 | 1596.7 | 2047.5 | 1275.2 | 1409.9 | 1636.3 |

| Direct costs (euro/ha) | 513.6 | 813.0 | 1156.3 | 601.2 | 780.3 | 981.5 |

| Land productivity (euro/ha) | 1500.5 | 2129.3 | 2966.0 | 1539.8 | 1661.1 | 2006.7 |

| Labor productivity (euro thousands/AWU) | 9.9 | 22.5 | 56.1 | 11.8 | 22.7 | 54.7 |

| Income (euro/ha) | 704.2 | 913.2 | 1265.3 | 528.5 | 586.8 | 709.3 |

| Income less subsidies (euro/ha) | 310.9 | 515.3 | 919.7 | 217.8 | 231.9 | 364.4 |

| Income (euro thousands/FWU) | 4.4 | 9.8 | 26.5 | 3.8 | 8.2 | 21.4 |

| Net investment rate (%) | −36.7 | 1.6 | 30.9 | −23.4 | 43.3 | 37.8 |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- ANCs subsidy rates contribute to the reduction of the processes of transferring agricultural land to non-agricultural purposes. In turn, a large share of Natura 2000 areas with obligatory restrictions for agricultural activities—harmful to the natural environment—minimizes the negative impact of agriculture on its condition. This is confirmed by the high share of areas with agriculture meeting the HNVf criteria;

- there is often a larger average UAA in farms. It is an understandable situation, due to the lower level of the obtained crops and in the situation of often limited possibilities of increasing the intensity of agricultural production, it is one of the basic methods of obtaining a larger scale of agricultural production and, as a result, enables achieving more favorable income from agricultural activity. This situation applies to communes with lowland ANCs;

- having poorer farming conditions entails a greater presence in the structure of agricultural land of permanent pasture, which is usually accompanied by the rearing of animals fed with roughage;

- farms contribute to a greater extent to the improvement and care of the natural environment, as evidenced by their greater propensity to conduct ecological agricultural production. For many of them, especially those who experience negative financial effects of conventional agricultural production, it is a real opportunity not only to maintain their viability, but also to increase their competitive ability, including through the development of agritourism. It must be added that the great value and diversity of the landscape is an exceptionally convincing circumstance to develop it in the areas.

- farms are characterized by lower costs per 1 ha of UAA, which results in lower production intensity. In their case, however, lower production intensity is associated with lower labor and land productivity. Farms from ANCs also obtain lower income per unit of UAA and are characterized by lower opportunities for further development. Only farms with the highest economic strength in these areas can implement investments increasing their ownership status.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stolte, J.; Tesfai, M.; Øygarden, L.; Kværnø, S.; Keizer, J.; Verheijen, F.; Panagos, P.; Ballabio, C.; Hessel, R. Soil Threats in Europe; JRC Technical Reports, EUR 27607; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. The relevance of sustainable soil management within the European Green Deal Land Use Policy. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture—Systems at Breaking Point; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Brondizio, E.S., Settele, J.J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Voluntary Guidelines for Sustainable Soil Management; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.E.; Jones, C.I. Why Do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output Per Worker than Others? Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrick, D.; Subramanian, A.; Trebbi, F. Institutions Rule. In The Primacy of Institutions over Integration and Geography in Economic Development; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, M.L.; Pereira, H.M. Towards a European Policy for Rewilding. In Rewilding European Landscapes; Pereira, H.M., Navarro, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schläpfer, F. External Costs of Agriculture Derived from Payments for Agri-Environment Measures: Framework and Application to Switzerland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiqui, P.S. Evolving economic landscapes: Why new institutional economics matters for economic geography. J. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 9, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijerink, G. New institutional economics: Douglass North and Masahiko Aoki. In Transformation and Sustainability in Agriculture: Connecting Practice with Social Theory; Vellema, S., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cory, G.A., Jr. (Ed.) The New Institutional Economics: The Perspective of Douglass North. In The Reciprocal Modular Brain in Economics and Politics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sammeck, J. A New Institutional Economics Perspective on Industry Self-Regulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J. Institution as the Fundamental Cause of Long-run Growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Aghion, P., Durlauf, S.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 385–472. [Google Scholar]

- Menard, C.; Shirley, M.M. (Eds.) The Domain of New Institutional Economics. In Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.K. (Ed.) New Institutional Economics. In The Economics of Transaction Costs Theory, Methods and Applications; Palgrave Mcmillan: London, UK, 2003; pp. 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, R. Essays on New Institutional Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of the Regions, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commmission to the European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Commmittee and The Commmittee of the Regions, Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- European Commission. Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EU Soil Strategy for 2030, Reaping the Benefits of Healthy Soils for People, Food, Nature and Climate; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- European Commission. Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Forging a Climate—Resilient Europe the New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Recommendations to the Member States as Regards Their Strategic Plan for the Common Agricultural; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Volk, T.; Rednak, M.; Erjavec, E.; Rac, I.; Zhllima, E.; Gjeci, G.; Bajramović, S.; Vaško, Ž.; Kerolli-Mustafa, M.; Gjokaj, E.; et al. Agricultural Policy Developments and EU Approximation Process in the Western Balkan Countries; Publications Office of the European Research Centre: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Orshoven, J.V.; Terres, J.M.; Tóth, T. Updated Common Bio-Physical Criteria to Define Natural Constraints for Agriculture in Europe: Definition and Scientific Justification for the Common Criteria; Technical Factsheets, JRC EC, EUR 25203 EN; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Terres, J.M.; Tóth, T.; Wania, A.; Hagyo, A.; Koeble, R.; Nisini, L. Updated Guidelines for Applying Common Criteria to Identify Agricultural Areas with Natural Constraints; JRC EC, EUR 27950 EN; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament of the Council Establishing Rules on Support for Strategic Plans to be Drawn up by Member States under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and Financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Van Eetvelde, V.; Antrop, M. Analyzing structural and functional changes of traditional landscapes—Two examples from Southern France. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 67, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giupponi, C.; Ramanzin, M.; Sturaro, E.; Fuser, S. Climate and land use changes, biodiversity and agri-environmental measures in the Belluno province, Italy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayas, J.M.R.; Martins, A.; Nicolau, J.M.; Schulz, J.J. Abandonment of agricultural land: An overview of drivers and consequences. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2007, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolbova, M. Eligibility citeria for less-favoured areas payment in the EU countries and the position of the Czech Republic. Agric. Econ.-Czech. 2008, 54, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovai, M.; Andreoli, M. Combining Multifunctionality and Ecosystem Services into a Win-Win Solution. The case study of the Serchio River Basin (Tuscany-Italy). Agriculture 2016, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polakova, J.; Soukup, J. Results of Implementing Less-Favoured Area Subsidies in the 2014–2020 Time Frame: Are the measures of Environmental Concern Complementary? Sustainbility 2020, 12, 10534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pažek, K.; Irgolič, A.; Turk, J.; Borec, A.; Prišenk, J.; Kolenko, M.; Rozman, Č. Multi-criteria assessment of less favoured areas: A state level. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2018, 58, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Council Directive of 28 April 1975 on mountain and hill farming and farming in certain less-favoured areas (75/268/EEC). Off. J. Eur. Communities 1975, 128, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Directive relative to the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of the Directive on mountain and- hill farming and- farming in certain less favoured areas adopted by the Council on 21 January 1974. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1974, 62, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Council Regulation (EC) No 1257/1999 of 17 May 1999 on Support for Rural Development from the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF) and Amending and Repealing Certain Regulations; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1999.

- European Commission. Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005 of 20 September 2005 on Support for Rural Development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Stuczyński, T.; Filipiak, K.; Kozyra, J.; Górski, T.; Jadczyszyn, J. Obszary o Niekorzystnych Warunkach Gospodarowania w Polsce; ISSPC-SRI: Pulawy, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dax, T. The redefinition of Europe’s Less Favoured Areas. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Conference-Rural Development in Europe Funding European Rural Development in 2007–2013, London, UK, 15–16 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Keenleyside, C.; Tucker, G.M. Farmland Abandonment in the EU: An Assessment of Trends and Prospects; Report Prepared for WWF Institute for European Environmental Policy; Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klepacka-Kołodziejska, D. Does Less Favoured Areas Measure support sustainability of European rurality? The Polish experience. Rural Areas Dev. 2010, 7, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawalińska, K.; Giesecke, J.; Horridge, M. The consequences of Less Favoured Area support a multi-regional CGE analysis for Poland. Agric. Food Sci. 2013, 22, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova-Mateva, Y. Effects of Less Favoured Areas support in territories with natural constraints. Trakia J. Sci. 2017, 15, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, K.; Eliasson, A.; Jones, R.; Le Bas, C.; Nachtergaele, F.; Pistocchi, A.; Ramos, F.; Rossiter, D.; Terres, J.M.; van Orshoven, J.; et al. Guidelines for Application of Common Criteria to Identify Agricultural Areas with Natural Handicaps; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2009; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, A.; Jones, R.J.A.; Nachtergaele, F.; Rossiter, D.G.; Terres, J.; van Orshoven, J.; Le Bas, C. Common criteria for the redefinition of intermediate less favoured areas in the European Union. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, R.P.O.; Fealy, R.; Creamer, R.E.; Towers, W.; Harty, T.; Jones, R.J.A. A review of the role of excess soil moisture conditions in constraining farm practices under Atlantic conditions. Soil Use Manag. 2012, 28, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on Support for Rural Development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Soulis, K.X.; Kalivas, D.P.; Apostolopoulos, C. Delimitation of Agricultural Areas with Natural Constraints in Greece: Assessment of the Dryness Climatic Criterion Using Geostatistics. Agronomy 2018, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Łopatka, A.; Koza, P. Assessment of the Functioning of Farms in Less-Favored Areas and in Areas of Significant Natual Value (LFA Specific type Zone I). Probl. Agric. Econ. 2020, 3, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerstwo Rolnictwa. Rozporządzenie Ministra Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi z dnia 1 lutego 2019 r. Zmieniające Rozporządzenie w Sprawie Szczegółowych Warunków i Trybu Przyznawania Pomocy Finansowej w Ramach Działania „Płatności dla Obszarów z Ograniczeniami Naturalnymi Lub Innymi Szczególnymi Ograniczeniami” Objętego Programem Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich na Lata 2014–2020; Ministerstwo Rolnictwa: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20190000262/O/D20190262.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Pastusiak, R.; Soliwoda, M.; Jasiniak, M.; Stawska, J.; Pawłowska-Tyszko, J. Are Farms Located in Less-Favoured Areas Financially Sustainable? Empirical Evidence from Polish Farm Households. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development in Poland. Informacja o Nowej Delimitacji ONW. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/delimitacja-onw-wedlug-nowych-zasad-ue (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- European Commission. Fine-Tuning in Areas Facing Significant Natural and Specific Constraints; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; p. 7. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/w11_anc_guidance_fine-tuning.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Jadczyszyn, J.; Kopiński, J.; Kuś, J.; Łopatka, A.; Madej, A.; Matyka, M.; Musiał, W.; Siebielec, G. Rolnictwo na Obszarach Specyficznych. Powszechny Spis Rolny 2010; Central Statistical Office: Warsaw, Poland, 2013.

- Zieliński, M. Environmental, organizational, and economic implications for agriculture in areas with different share of the Natura 2000 network. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2022, 371, 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łopatka, A.; Koza, P.; Siebielec, G. Propozycja Metodyki Wydzieleń Zasięgów Obszarów ONW Typ Specyficzny wg tzw. Kryteriów Krajowych, 2017; ISSPC-SRI: Pulawy, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prandecki, K.; Wrzaszcz, W.; Zieliński, M. Environmental and Climate Challenges to Agriculture in Poland in the Context of Objectives Adopted in the European Green Deal Strategy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laktić, T.; Malovrh, S.P. Stakeholders Participation in Natura 2000 Management Program: Case Study of Slovenia. Forests 2018, 9, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Technical Handbook on the Monitoring and Evaluation Framework of the Common Agricultural Policy 2014–2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- European Commission. Working Dokument: Practices to Identify, Monitor and Assess HNF Farming in RDPs 2014–2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Gardi, C.; Visioli, G.; Conti, F.D.; Scotti, M.; Menta, C.; Bodini, A. High Nature Value Farmland: Assessment of Soil Organic Carbon in Europe. Front. Environ. Sci. 2016, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, Y. Trends in High Nature Value farmland studies: Asystematic review. Eur. J. Ecol. 2017, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jadczyszyn, J.; Zieliński, M. Assessment of farms from High Nature Value Farmland areas in Poland. Ann. PAAAE 2020, 22, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzaszcz, W.; Zieliński, M. Sustainable Development of Agriculture in Poland—Towards Organization and Biodiversity Improvement? Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 11, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmieliński, P.; Wrzaszcz, W.; Zieliński, M.; Wigier, M. Intensity and Biodiversity: The ‘Green’ Potential of Agriculture and Rural Territories in Poland in the Context of Sustainable Development. Energies 2022, 15, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Generated by the Agency for Restructuring and Modernization of Agriculture in Poland on the Basis of Farm Payment Applications for the 2016 and 2021 Campaigns in Terms of Communes, Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/arimr (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Data Generated by the Agency for Restructuring and Modernization of Agriculture in Poland Based on Applications of Farms for Organic Payments for the 2021 Campaign, Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/arimr (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Li, L.; Wen, Z.; Wei, S.; Lian, J.; Ye, W. Functional Diversity and Its Influencing Factors in a Subtropical Forest Community in China. Forests 2022, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mites, M.; García-Mozo, H.; Galán, C.; Oña, E. Analysis of the Orchidaceae Diversity in the Pululahua Reserve, Ecuador: Opportunities and Constraints as Regards the Biodiversity Conservation of the Cloud Mountain Forest. Plants 2022, 11, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zeng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, D.; Liu, W.; Ma, Z.; Wu, B. Assessing the Impact of Soil on Species Diversity Estimation Based on UAV Imaging Spectroscopy in a Natural Alpine Steppe. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natura 2000 w Polsce. Available online: https://natura2000.gdos.gov.pl/natura-2000-w-polsce,GDOŚ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Statistics Poland. Informacja o Wstępnych Wynikach Powszechnego Spisu Rolnego 2020; The Agriculture Census 2020; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- Prišenk, J.; Turk, J. Assessment of Concept between Rural Development Challenges and Local Food Systems: A Combination between Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis and Econometric Modelling Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziętara, W.; Mirkowska, M. The Green Deal: Towards Organic Farming or Greening of Agriculture? Probl. Agric. Econ. 2021, 3, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Generated from the FADN in the Years 2018–2020. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/880bbb5b-abc9-4c4c-9259-5c58867c27f5/library/ec2965e9-dd36-4e13-8ce1-649a3f8b681e?p=1&n=10&sort=modified_DESC (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Abramczuk, Ł.; Augustyńska, I.; Czułowska, M.; Skarżyńska, A. Produkcja, Koszty i Dochody Wybranych Działalności Rolniczych w Latach 2018–2019; IAFE-NRI: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abramczuk, Ł.; Augustyńska, I.; Czułowska, M.; Goławska, M. Produkcja, Koszty i Dochody Wybranych Działalności Rolniczych w Latach 2019–2020; IAFE-NRI: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Data Generated by the Polish FADN in the Years 2018–2020, Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://fadn.pl/ (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Papić, R. Rural development policy on areas with natural constraints in the Republic of Serbia. Econ. Agric. 2022, 69, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwicz, L. Inventing New Institutions: The Design Perspective. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1987, 69, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Definition and Threshold Value | Coverage in Poland (% of UAA) |

|---|---|---|

| Low temperature * | Length of growing period (number of days) defined by number of days with daily average temperature > 5 °C ≤ 180 days | ** |

| Thermal-time sum (degree-days) for growing period defined by accumulated daily average temperature > 5 °C ≤ 1500 degree-days | 3.1 | |

| Dryness * | Ratio of the annual precipitation (P) to the annual potentialevapotranspiration (PET) ≤ 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Excess Soil Moisture * | Number of days at or above field capacity ≥ 230 days | ** |

| Limited Soil Drainage | Wet within 80 cm from the surface for over 6 months, or wet within 40 cm for over 11 months * | ** |

| Poorly or very poorly drained soil | ** | |

| Gleyic color pattern within 40 cm from the surface | 0.6 | |

| Unfavorable Texture and Stoniness | ≥15% of topsoil volume is coarse material, including rock outcrop, boulder | 0.9 |

| Texture class in half or more (cumulatively) of the 100cm soil surface is sand, loamy sand defined as: silt% + (2 x clay %) ≤ 30% | 41.3 | |

| Topsoil texture class is heavy clay (≥ 60% clay) | ** | |

| Organic soil (organic matter ≥ 30%) of at least 40 cm | 5.5 | |

| Topsoil contains 30% or more clay and there are vertic properties within 100 cm of the soil surface | 0.3 | |

| Shallow Rooting Depth | Depth (cm) from soil surface to coherent hard rock or hard pan ≤ 30 cm | 0.3 |

| Poor Chemical Properties | Salinity: ≥ 4 deci-Siemens per meter (dS/m) in topsoil | ** |

| Sodicity: ≥ 6 Exchangeable Sodium Percentage (ESP) in half or more (cumulatively) of the 100 cm soil surface layer | ** | |

| Soil Acidity: pH ≤ 5 (in water) in topsoil | 1.7 | |

| Steep Slope | Change of elevation with respect to planimetric distance (%) ≥ 15% | 3.1 |

| Variable | Communes with at Least 75% Share of ANCs in UAA: | Remaining Communes with ANCs | Communes without ANCs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCs Zone 1 | ANCs Zone 2 | ANCs Specific Zone 1 | ANCs Specific Zone 2 | ANCs Mountains | ANCs in Total | |||

| Number of communes | 286 | 184 | 50 | 83 | 64 | 632 | 850 | 328 |

| APAV indicator (points) | 61.0 | 44.6 | 63.0 | 59.5 | 40.3 | 55.0 | 72.6 | 86.5 |

| NTI indicator (points) | 39.9 | 54.1 | 48.6 | 59.5 | 60.1 | 44.5 | 29.5 | 21.3 |

| Natura 2000 share in the total area (%) | 22.1 | 33.0 | 34.9 | 28.7 | 51.7 | 28.2 | 17.6 | 9.6 |

| Share of the HNVf with moderate natural value in total UAA (%) | 26.1 | 47.9 | 35.6 | 39.6 | 83.2 | 35.9 | 19.7 | 10.4 |

| Share of the HNVf of high natural value in total UAA (%) | 16.7 | 32.4 | 25.5 | 26.1 | 37.8 | 21.9 | 11.3 | 4.3 |

| Share of the HNVf with extremely high natural value in total UAA (%) | 13.3 | 25.9 | 20.6 | 22.4 | 34.8 | 17.5 | 8.6 | 3.3 |

| Variable | Communes with at Least 75% Share of ANCs in UAA: | Remaining Communes with ANCs | Communes without ANCs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCs Zone 1 | ANCs Zone 2 | ANCs Specific Zone 1 | ANCs Specific Zone 2 | ANCs Mountains | ANCs in Total | |||

| Number of organic farms (thous.) | 2.8 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 6.9 | 4.8 | 0.7 |

| Average UAA of an organic farm (ha) | 51.7 | 30.8 | 45.8 | 29.7 | 26.1 | 39.9 | 40.7 | 30.3 |

| Share of organic farms with livestock production (%) | 33.3 | 51.7 | 41.9 | 48.6 | 83.2 | 26.0 | 36.2 | 22.6 |

| Ecological UAA (thousand ha), including: | 89.7 | 29.2 | 22.1 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 156.6 | 109.5 | 12.9 |

| -arable land (thousand ha) | 83.5 | 24.7 | 19.8 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 141.7 | 97.0 | 11.0 |

| -permanent grassland (thousand ha) | 5.3 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 12.7 | 8.7 | 0.6 |

| -permanent crops (thousand ha) | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 1.3 |

| Share of UAA with organic production in its total area supported under the CAP 2014-2020 (%) | 20.9 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 36.4 | 25.4 | 3.0 |

| Share of UAA with organic production supported under CAP 2014-2020 in total UAA (%) | 4.9 | 3.8 | 7.1 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 0.7 |

| Variable | Communes with at Least 75% Share of ANCs in UAA: | Remaining Communes with ANCs | Communes without ANCs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCs Zone 1 | ANCs Zone 2 | ANCs Specific Zone 1 | ANCs Specific Zone 2 | ANCs Mountains | ANCs in Total | |||

| Share of cereals in arable lands (%) | 73.5 | 77.6 | 67.6 | 59.9 | 42.6 | 75.9 | 71.2 | 69.3 |

| Share of structure-forming plants and grasses in arable lands (%) | 10.9 | 14.8 | 18.3 | 27.8 | 49.9 | 12.7 | 8.7 | 6.3 |

| Share of root crops in arable lands (%) | 3.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| Share of oilseeds in arable lands (%) | 8.7 | 1.4 | 8.4 | 6.1 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 11.2 | 15.1 |

| Share of fallow lands and fallow lands with honey plants in arable lands (%) | 1.8 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| Share of plants remaining in arable lands (%) | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| Shannon–Wiener index (%) | 2.55 | 2.25 | 2.44 | 1.88 | 1.28 | 2.47 | 2.43 | 2.18 |

| Variable | Farms from ANCs: | Farms without ANCs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Total (without ANCs Mountains) | Mountains | ||

| Total costs (euro/ha) | 1648.5 | 1560.7 | 2627.4 |

| Direct costs (euro/ha) | 709.1 | 618.4 | 1133.0 |

| Land productivity (euro/ha) | 1533.7 | 1301.3 | 2763.7 |

| Labor productivity (euro thousand/AWU) | 63.6 | 39.3 | 77.1 |

| Income (euro/ha) | 283.7 | 267.3 | 489.9 |

| Income without subsidies (euro/ha) | −104.5 | −253.6 | 139.6 |

| Income (euro thousands/FWU) | 21.8 | 15.2 | 29.3 |

| Net investment rate (%) | 23.2 | 11.8 | 24.8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zieliński, M.; Koza, P.; Łopatka, A. Agriculture from Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints (ANCs) in Poland, Its Characteristics, Directions of Changes and Challenges in the Context of the European Green Deal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911828

Zieliński M, Koza P, Łopatka A. Agriculture from Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints (ANCs) in Poland, Its Characteristics, Directions of Changes and Challenges in the Context of the European Green Deal. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911828

Chicago/Turabian StyleZieliński, Marek, Piotr Koza, and Artur Łopatka. 2022. "Agriculture from Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints (ANCs) in Poland, Its Characteristics, Directions of Changes and Challenges in the Context of the European Green Deal" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911828

APA StyleZieliński, M., Koza, P., & Łopatka, A. (2022). Agriculture from Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints (ANCs) in Poland, Its Characteristics, Directions of Changes and Challenges in the Context of the European Green Deal. Sustainability, 14(19), 11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911828