Abstract

Managing landfill waste is essential to sustainable resource utilization. With a focus on the luxury fashion industry, this paper highlights the role that sustainable and social innovations can play in reducing environmental waste and improving social outcomes. Elvis & Kresse is a purpose-driven case study, because it was founded to eradicate a problem that had thus far received little attention, namely the problem of disposing of end-of-life fire-hoses. From a business model and circular economy perspective, this article explains how the company’s rescue–transform–donate model has helped to build a sustainable and socially oriented yet profitable luxury brand. The analysis of the case suggests that for scholars, the typical business model canvas merits some revision beyond the current business focus on the financial bottom line to account for the social and ethical dimensions. For practitioners, this case demonstrates how the circular economy can be compatible with luxury fashion by turning waste into durable, fashionable products.

1. Introduction

Fast fashion has been criticized for promoting overconsumption and materialism [1,2]. Vast volumes of waste are produced in the manufacturing processes of the fashion industry, and these continue to rise. For instance, an estimated 800,000 tons of leather waste is generated by the global leather industry alone each year [3]. Overconsumption by society and the associated overproduction by businesses contribute to dangerous, overflowing landfills.

Luxury goods can sometimes be incompatible with sustainability by requiring rare, exotic, and unique natural materials, such as fur, leather, and ivory. The rarer and more limited the material, the more expensive and exclusive it becomes. For luxury goods in particular, which are based on exclusivity, it can be difficult to justify using more accessible alternative materials [4]. Additionally, the production of luxury goods relies on distributed global supply chains to source materials from around the world [5], thus adding to the carbon emissions for transporting materials and goods. In contrast, another aspect in the creation of luxury goods is the use of highly skilled craftspeople to produce bespoke products in small batch units. This model in the luxury industry can work in favor of sustainability if production is localized and the process incorporates a unique value-creation model centered on the circular economy. This potentiality is what is explored in this paper.

Fortunately, prominent players in every industry, including the luxury fashion one, are basing their long-term strategies on fundamental values that underpin sustainable businesses, such as transparency, slow fashion, and closing the loop. However, while some players purport to support sustainability, there is often little evidence to support their claims. In a study of the 45 luxury companies in China that published sustainability reports for the 2017–2018 period, only eight reported on the sourcing of materials for their luxury goods [6], which should be concerning given that the fashion industry accounts for 10% of annual global carbon emissions, which is more than all international flights and the maritime shipping industry combined [7]. However, young consumers of luxury goods are increasingly demanding that sustainability in terms of environmental and social issues be reflected in such goods [8].

Broadly speaking, three drivers are pushing the luxury industry to adopt sustainability: market benefits, operational benefits, and laws and regulations [9]. The focus here is on the first two of these. In terms of market benefits, consumers are increasingly demanding sustainable products and processes, including in the fast fashion sector [10], and customer interest and loyalty can be enhanced through sustainability [11]. In Italy, for instance, young consumers prefer that recycled or recyclable materials be used in the manufacture of products [8]. However, a survey also conducted in Italy found that the emergence of a sustainability bias in the fashion sector should be considered [12]. Consumers’ willingness to pay for second-hand items can be limited due to perceptions of poor quality, so price satisfaction and quality assurance are relevant drivers for producing durable garments that can be resold [12].

In terms of operational benefits, firms can rely more on local sources of raw materials and skills, thus minimizing disruption risks to its supply chain. A study of 175 US companies found that an orientation toward an advanced level of sustainability combined with a long-term perspective had the greatest positive effect on operational performance in terms of product quality, process improvements, and lead time [13].

Overstock issues are common within fashion brands, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this problem and amplified the public’s awareness of environmental and social concerns in most supply chains for clothing and accessories. Criticism of unsustainable practices is on the rise since the pandemic, prompting sustainability-driven buying decisions. For instance, 65% of McKinsey’s survey respondents in 2021 declared that their purchasing intentions had shifted toward durable, high-quality products [2]. With consumers becoming more environmentally and socially conscious, firms need to adopt new business models, products, and services to align with their customers’ beliefs and remain competitive [14].

A business model is a tool through which a company determines its competitive strategy. This model encompasses various elements, such as the value proposition or offering and value-creation and -capture, such as the activities, resources, costs, distribution channels, revenue streams, and partners that together form the competitive advantage [15]. If fashion companies, especially in the luxury sector, want to decrease their environmental impact by optimizing resource usage to reduce waste and foster social well-being, a circular economy business model can be adopted [16]. However, business models have traditionally focused, and continue to do so, on costs and revenues (i.e., the bottom line). In contrast, circular economy models return the focus to the economic and environmental aspects from a supply chain, operations, and production perspective [17]. Murray et al. [18] noticed that the literature and practice for circular economies concentrate on redesigning supply chains to achieve an ecological benefit.

Unfortunately, the social and ethical dimensions are barely mentioned, yet these should be considered as crucial aspects that contribute toward the adoption of sustainable business models [18]. Similarly, Bocken et al. [19] suggested that a systems thinking approach is needed to account for the wider consequences of circular strategies. Such an approach suggests that not only the economic and environmental aspects should be evaluated but also the social perspective. Moreover, sustainable business models should capture social value in addition to economic and environmental value. Thus, according to the archetypes of sustainable business models used by Bocken et al. [15], the primary forms of innovation are organizational, technological, and social in nature. Innovations belonging to the social category aim to enhance the positive impact of a company on society over the long term.

From a theoretical perspective, how business models can be adapted to account for the social aspects of a business is explored in this study, while from a practical perspective, how the incompatibilities between the luxury sector and sustainability can be overcome is also explored. To this end, a case study of the luxury accessories brand Elvis & Kresse was reviewed to reflect on the concept of waste and how it can be reconsidered as a resource to replace the expensive raw materials normally used to produce luxury products. The paper next outlines the methods, presents the results of exploring and analyzing the case study, and reflects on the case study through a discussion of theory and practice.

2. Materials and Methods

An exploratory case study was selected, seeing as it is an acknowledged method for social science research that has been used to exemplify sustainability practices [20,21]. A purpose-driven business with an environmental and social focus on building a sustainable luxury brand was selected. The Elvis & Kresse case is unique in that in 2005, it set out to solve the unaddressed problem of waste fire-hoses in the UK. An analysis of its business model may offer lessons and provide motivation for other luxury companies seeking to adopt sustainable practices. Particular attention is paid to the supply chain in order to examine how the upstream input of alternative raw materials affects the downstream activities [9].

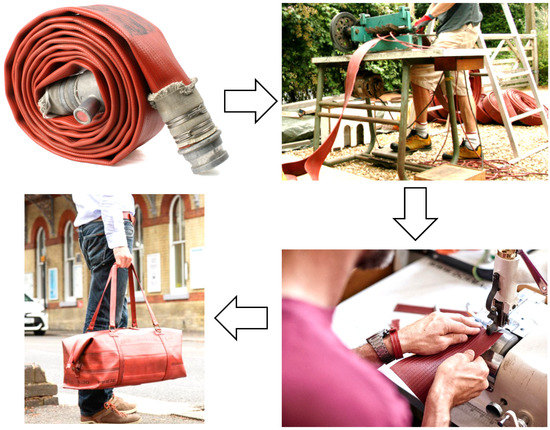

This study employed the case method based on secondary data, as conducted in prior studies to assess sustainable value creation in the luxury industry [5] and the sustainable supply chain in the fashion industry [20]. In line with these prior studies, first, data were compiled from publicly available sources, primarily podcasts, the firm’s website, annual sustainability reports, news media, and industry reports. However, a second methodological step incorporated beyond these papers is that the company and its founders were contacted after drafting the case study to verify information about the business and operational model. The company provided clarification about its history and early stages of the business as well as shared photos of the manufacturing process (Figure 1). One of the founders also reviewed the final paper and provided a signed consent for publication. Table A1 in Appendix A lists eleven interviews and podcasts that featured the founders, and these served as an important source of data. This was complemented with 19 webpages from the company’s website and blog posts, as listed in Table A2 in Appendix A. In addition, news media and annual reports from the fashion industry, as published by global consulting firms, were also accessed. These diverse sources of data helped to verify insights and therefore enhance the reliability of the findings. After listening to five of the eleven interviews, no further insights about the company’s business model were gleaned from the other six podcasts, meaning that saturation was reached in terms of data collection and analysis. Consequently, a direct discussion was held by email with one of the founders to clarify and verify the information and analysis in the paper (item 12 in Table A1).

Figure 1.

From fire-hose to handbag (photos provided by Elvis & Kresse).

Data and information about the case were compiled, structured, and presented per the questions found in prior research for documenting an innovative case study [22]. This case study template provided the authors with guidance for extracting relevant information from the various sources of data. Analytically, a business model framework that was adapted for circular economies by Lewandowski [16] was used to assess the environmental aspects of Elvis & Kresse’s business model. Next, the responsible business model framework developed by Pepin et al. [23] was used to assess the social aspects of the same business model. For discussion, several papers were reviewed to reflect upon Elvis & Kresse’s approach in comparison to existing linear and circular economy models [14,17,24,25,26,27,28].

3. Results

This section presents the results alongside some questions pertaining to the case study’s conception of innovation, the key features of the business, the business model, the operating model, diffusion, challenges, and impacts.

3.1. How Was the Innovation Conceived?

Elvis & Kresse is a design-led company that solved a waste problem that nobody else saw potential in. The company was established to prevent decommissioned fire-hoses from ending up in landfills. When Kresse Wesling and her partner Elvis arrived in the UK in 2004, they had to decide which industry they should target, the kind of product they should produce to solve the problem, and most importantly, how to have the most significant positive impact. Kresse researched the landfill situation in the UK and found that around 100 million tons of waste were being dumped in that year, and she felt a need to help solve the problem. Thus, in 2005 during a coincidental meeting with the London Fire Brigade, she discovered that damaged and decommissioned fire-hoses were ending up in landfills after 25 years of use.

This undesirable situation was occurring because fire-hoses are designed to survive fire and high-temperature environments, so the material they were made from could not be shredded and melted to produce new ones. Kresse realized that these hoses had too much potential to be sent to the scrapheap, but nobody else was looking at them as a potential material resource. Consequently, she and her partner resolved to save London’s decommissioned fire-hoses. To do this, they first had to truly analyze the problem and understand issues such as the location and amount of waste. They met with the fire-hose manufacturer to learn about the composition and lifecycle of a hose and also conducted extensive research themselves, turning themselves into experts on fire-hose waste in the process. Kresse described the challenge and opportunity as follows:

“Fire-hose can’t be recycled because it is a double wall nitrile rubber jacket that is extruded through and around a nylon woven core... because it is a composite it can’t be shredded and melted and made into new hose. We landed on luxury because our research showed that this amount of material, the type of material, the condition of the material etc. meant it was not suitable for anything else.”

The founders spent considerable time exploring ways to use hoses, by cleaning them in the bathtub and using household devices such as kitchen scissors and pizza cutters to experiment with the material until they came up with the idea of making belts. From that moment on, their goal for the fire-hoses became to treasure them and craft every piece with the highest level of skill to ensure a long and healthy second life for waste.

3.2. What Key Features Make the Business Unique?

The Elvis & Kresse business encompasses three pillars, namely rescue, transform, and donate. The fire-hoses, on becoming no longer suitable for use as life-saving devices, are rescued and then transformed into classic accessories, such as wallets, handbags, and belts. Finally, half of the profits are donated to charities.

The first pillar (rescue) was originally served by giving decommissioned fire-hoses a second life, so their business operates by using only rescued materials and doing everything possible to ensure those materials have a second life for as long as possible. For Elvis & Kresse, the design process started with a problem rather than with an idea. In other words, the material and the magnitude of the problem dictated what was to be made. Then, moving beyond the fire-hose, Elvis & Kresse sought other resources that could be reclaimed. These included parachute silk for lining bags and wallets, printing blankets discarded by the off-set printing industry, and leather fragments. In 2017, they associated with the Burberry Foundation to address the immense problem of leather waste. Through a five-year partnership, the brand expects to recraft 120 tons of Burberry’s discarded leather scraps into new luxury accessories and homeware.

The second pillar (transform) in Elvis & Kresse’s DNA converts rescued materials into luxury goods. They focus on handcrafting timeless, quality, classic designs in order to make unique products that will last beyond a single season, thus defying the seasonality that prevails in the fashion industry and facilitating a long product lifespan. The company is committed to producing products that will be desirable in the long term despite their rescued origin. They recruit highly skilled craftspeople to make genuine, honest, practical accessories that will be among the best in the world. Leather fragments provided by Burberry are transformed into components to be handwoven into new hides or used in accessories, such as belts, handbags, wallets, cufflinks, and covers for phones and tablets. Furthermore, the company uses waste to support operational needs, such as by transforming jute coffee sacks into string for tags, flattening shoeboxes left at stores to make their packaging, using tea sacks to help create brochures and mailing pouches, and using auction banners from past events to line large handbags. A customer’s pre-owned family tent was even at one stage used to produce 248 dust covers and packaging items.

For the third pillar (donate), Elvis & Kresse believes that making money and doing good can go hand in hand, so its business model includes donating half of its profits to charities associated with the reclaimed resources they use. For instance, they donate half of the profits from the fire-hose-based products to the Fire Fighters Charity and half of the profits from leather-based products to the Barefoot College. Thus, giving back to society is core to how they define business success.

3.3. What Is the Business Model?

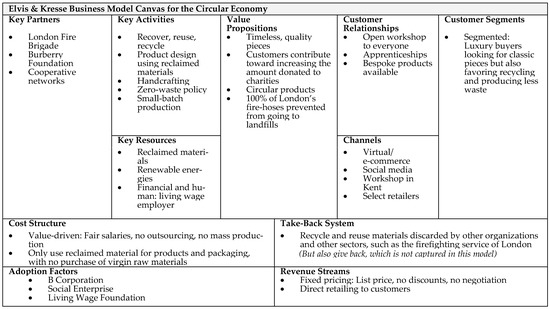

Elvis & Kresse is a purpose-driven business. To further understand Elvis & Kresse’s approach to circularity, Figure 2 depicts the company’s business model according to the Lewandowski [16] template, which builds upon the traditional business model canvas developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur [28] by adding the “Take-back system” and “Adoption factors” components. Elvis & Kresse’s business model can be understood in terms of the circular economy, which involves activities such as minimizing the use of raw materials, developing products so parts can be easily dismantled and reused in other systems, and prolonging product life through maintenance and repair. It also relies on using recycled materials to create new products, thus preventing waste material from going to landfills. Before the circular economy was a topic of interest, Elvis & Kresse called itself a backward designer, and this is what inspired it to create its system of Lego-like leather pieces to make rugs. By circularly designing their products, the leather components can be woven to make a new piece. Thus, there must be perpetual reuse and recycling with a focus on reducing consumption. However, recycling involves greater complexity than reuse and repair and generally needs more energy and water [20], so such an enterprise should be powered by renewable energy if it is not to defeat the purpose of the circular economy [29].

Figure 2.

The business model of Elvis & Kresse (authors’ work based on canvas adapted from Lewandowski [16]).

Elvis & Kresse focuses on multiple objectives as part of its business strategy, asserting that a problem cannot be solved sustainably if the solution generates another problem. Therefore, aside from rescuing materials and donating to charities, it tries to be a social enterprise and a living wage employer, a user of renewable energies, and a provider of apprenticeships. It never applies discounts to its products, with it believing that relying on discounts to sell products gives businesses an excuse to overproduce, resulting in even more waste. They saliently and proudly shun sales events such as Black Friday.

Per the open innovation approach, it considers itself a transparent business, one that is available to be learned from, and it is willing to share its ideas and business model with others hoping to replicate them. This partly explains why this study could draw on several publicly available interviews and podcasts involving the founders for data (we later successfully approached the company for further information). In addition, such transparency derives from the fact that Elvis & Kresse is a social enterprise, one that is open to replication of its business model. Its social mission directs its operations, with it dedicating half of its profits to social causes. As such, it only makes a business decision if it will likely contribute to a better world for future generations.

3.4. What Is the Operating Model?

Every piece is produced by Elvis & Kresse, with nothing being outsourced, to assure each item is ethically made and complies with their quality and environmental standards. The company functions contrary to the fast-moving consumer goods sector because it believes in slow design and production. Indeed, as all the materials are rescued, preparing and transforming them takes time. All their products are also made to last, such as by using highly robust fire-hose material, which lasts well beyond the 25 years in which it was originally used for firefighting.

Products are produced in small batches because its workshop team is happier when working on various items as opposed to mass-producing products on an assembly line model. Furthermore, quality is easier to control in smaller batches, thus avoiding over-producing stock that may subsequently be wasted. For example, some luxury firms, such as Burberry, have incinerated excess products rather than sell them at a discount, because cheap products may damage their expensive and exclusive brand image. The drawback of small batch production for Elvis & Kresse is that some of their rescued raw materials are rare and cannot be restocked on demand, so if they run out of them, they must wait until more can be rescued before continuing production. However, an advantage of this is that every Elvis & Kresse item is unique and exclusive.

As such, Elvis & Kresse does not believe that the number of people employed by a company is a measure of its success. It only has high-quality, full-time jobs and does not rely on seasonal workers, so it cannot easily scale up its production. When selecting its work team, it looks for people with the attitude, aptitude, and willingness to be part of something important that will have an impact. It tries to have a lean team without a hierarchical structure, unlike in big companies where it can be difficult to innovate. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the founders and the craftspeople managed to collectively adapt their work procedures to comply with the government’s social distancing and safety measures.

3.5. How Is the Innovation Spread?

A clear purpose, partnerships, and the production of high-quality products help to spread the company’s innovations based on word of mouth and ethical reputation. The authenticity behind Elvis & Kresse as a brand has served to capture the attention of the media and the public. It has also emphasized the importance of their work by giving back to charities, being a certified social enterprise and a founding UK B Corporation, developing strategic partnerships such as the one with Burberry Foundation, offering apprenticeships, and serving on the board of the Keep Britain Tidy charity. In addition, through retailers that carry its stock, it has managed to diffuse its products across at least nine countries.

It is also expanding by diversifying its use of rescued materials. On eradicating the problem of fire-hoses ending up in landfills in the UK, Elvis & Kresse established a partnership with Burberry Foundation to address the problem of leather waste. Then, in 2020, it set out on another mission to address the problem of 16 million aluminum cans being littered in public spaces every year in the UK as well as the two billion cans that do not get recycled because they are put in the wrong bins. It therefore proposed a complex, multifaceted solution to tackle this problem. This comprised collecting the cans and designing, testing, and open sourcing a small-scale, renewably powered forge that would be safe and easy to build and adapt. It expects this solution will be shared and used for good, but its own goal with this project is to design and produce circular aluminum hardware at Elvis & Kresse, such as belt buckles, rivets, and D-rings.

3.6. How Were the Major Challenges Overcome?

To be successful, Elvis & Kresse deems that it is essential to stay devoted to the problem, which is the avoidable disposal of waste materials in this case, and adapt the business as necessary to continue addressing it while delivering measurable real change. For instance, by remaining dedicated to solving the problem of waste fire-hoses, it has had a sustained impact even as its solution evolved over time.

Elvis & Kresse faced one of its biggest challenges before the brand was even established. After pledging to solve the problem of waste fire-hoses, it found that no factories in Western Europe wanted to work with fire-hose material because it was not leather. On searching for a processing facility, it eventually found one in Romania that decided to take a chance on it and became its first partner. Burberry later bought the entire capacity of this Romanian factory, but this was no reason for Elvis & Kresse to abandon its project because it had already found a way to solve the problem of waste fire-hoses, and its donations were increasing. It was not going to allow an external factor to derail its purpose-driven business model when everything inside the company was going so well. Consequently, it found a mill in Kent and restored it, so it could use it as its own manufacturing facility.

After setting the goal of becoming a net regenerative company by 2030, it adopted the use of renewable fuel and expanded operations at the mill to ensure sustainable growth. What had looked like a challenge turned out to be a good opportunity, because its local production made coordination less complex and reduced the risk of disruption to the supply chain, such as from Brexit, as well as reduced the carbon emissions associated with the transportation of goods and materials during the production process.

3.7. How Is the Impact Evaluated?

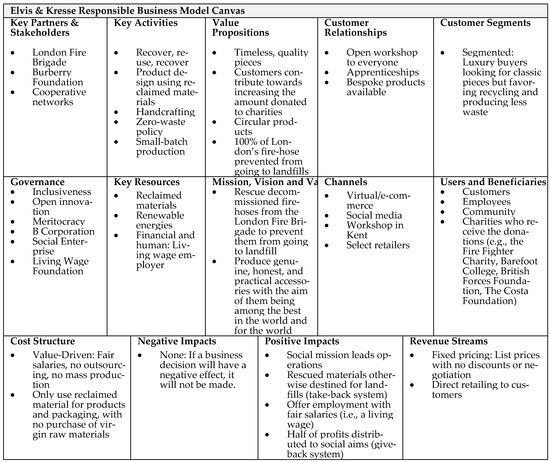

Many traditional businesses can only measure their success in one way, namely through profits. Elvis & Kresse’s impact has been recognized by becoming a certified B Corporation, which is a new type of business that aims to find a balance between the people and the planet. B Corporation certification implies that a company upholds the highest standards in its overall environmental and social performance, thus helping consumers to identify businesses that are genuinely making a difference [30]. Figure 2 was constructed to capture the impact of the business in terms of the financial and environmental bottom lines, but Figure 3 represents an alternative approach for mapping a business model without excluding the social impact. This is based on the responsible business model canvas that was developed at the Université Laval [23]. Although Elvis & Kresse does not celebrate making money as such, it does consider it because it is what allows it to remain operating. In addition, however, there are two extra measures of success, namely the amount of waste rescued from landfills and the amount of money donated to charities. Each of these three measures has equal relevance for it, and they are captured within the “Users and beneficiaries” and “Governance” fields in the responsible business model, which better reflects Elvis & Kresse’s impact-driven business.

Figure 3.

The responsible business model of Elvis & Kresse (authors’ work based on canvas adapted from Pepin, Tremblay and Audebrand [23]).

In only five years, Elvis & Kresse solved the problem of waste fire-hoses. It reclaimed more than 200 tons of them and continues to be the only reason why fire-hoses are no longer sent to landfills. The donation of half of the profits to the Fire Fighter Charity has helped enhance the lives of firefighters and their families by providing them with mental or physical therapy and food vouchers when needed. This has also resulted in invaluable support for many during the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, thanks to its partnership with Burberry Foundation, it expects to transform at least 120 tons of leather cut-offs into luxury goods, with half of the profits from this project going to the Barefoot College charity. Furthermore, although it initially aimed to sponsor only one scholarship, its business has become successful enough to cover three grants instead. This has enabled three Guatemalan women to be trained as Barefoot Solar Engineers, so they will be capable of installing renewable solar lighting systems for their villages, thus reducing carbon emissions and enhancing the social and economic wellbeing of the villagers. Additionally, thanks to a willingness to share knowledge with others, the British Council used Elvis & Kresse’s videos to inspire future entrepreneurs in Egypt, resulting in fourteen new waste-reclamation ideas to emerge.

4. Discussion

The theoretical and practical contributions of this study with respect to business models and the circular economy are discussed.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

The case study of Elvis & Kress supports the notion that sustainability can be a key driver of innovation [31]. The company lent new life and prestige to materials that were previously considered solely as waste by embracing a sustainability-led innovation perspective. It was not about pursuing a profit-oriented business idea and later trying to become sustainable [32]. The business began by looking at a sustainability-related problem that needed resolution. By viewing compliance as an opportunity rather than a statutory requirement, the company developed an operating model that in addition to not harming the environment actively helped to protect it. Elvis & Kresse relies on the circular economy to offer high quality, practical products that will have a long life, and it has been at the forefront of change by only using waste material to make products that are not only sustainable but also luxury, thereby giving them a long second life. In addition, because it produces timeless, zero-waste products, including the packaging, in a workshop powered by renewable energy, its entire value chain is more sustainable. Furthermore, through its project to rescue waste aluminum with a small-scale, renewably powered forge, Elvis & Kresse has shown it is keen to create a next-practice platform and share its sustainable innovations openly.

In contributing to the components of the business model, this case study suggests that the traditional business model canvas needs to be extended to account for the sustainability and social aspects of a business. The Lewandowski [16] canvas helped to account for the circular economy in Elvis & Kresse’s rescue and transformation pillars. The company’s contribution in rescuing hard-to-decompose materials from landfills, in addition to its recognition as a B Corporation, underpins its claim to be a sustainable brand based on a sustainable business model. However, the take-back system does not account for the give-back element of Elvis & Kresse’s business model (see Figure 2), but the responsible business model canvas of Pepin et al. [23] helped to account for the social aspect of the donation pillar.

Prior research outlined several business models for the implementation of a circular economy, with product and process design determined to be among the most prevalent approaches [33]. Indeed, Elvis & Kresse too relies on the technological dimension, in terms of both product and process design, to craft luxury and long-lasting products originally sourced from waste material. However, the company has also demonstrated the need to incorporate the social and ethical dimensions to complete the full circle of the circular economy more comprehensively in their business model. A consideration of the entire business model beyond products and processes can provide a competitive advantage to those companies who deliver value based on sustainability and social outcomes. Such innovations go beyond incremental improvements and approach a more holistic entrepreneurial and strategic form of innovation [34] that will impact every aspect of a company’s business.

For Elvis & Kresse, designing and producing luxury products while addressing environmental concerns supports sustainable innovation, while donating half of the profits to charity supports social innovation. The company therefore targets a self-sustaining rather than a profit-maximizing business, such as by electing not to engage in sales and discounts, thus steering consumers away from overconsumption. With its process innovations concentrating on a social purpose for the products it sells, its operational impact on the planet and the people it trains and hires, and its distribution of profits, it serves as a social enterprise that is focused on a triple bottom line [35]. Thus, the analysis of this case study found that a strong relationship exists between the pursuit of sustainability for the environment and social wellbeing, thus addressing demands from consumers for luxury companies to pursue goals beyond simply economic ones [8].

In contributing to components of the circular economy, those described in the existing literature were also reviewed. The circular economy, or circularity, implies that the need for new raw materials is reduced by reusing or recycling existing ones. This model is usually underpinned by the “3R” principles of energy and materials, which comprises reducing, reusing, and recycling. However, as the role of sustainability as a driver of innovation has grown, several authors have recently proposed recover, redesign, and remanufacture, as a further three “Rs” that should be considered when pursuing a circular economy approach [14,24,25]. Moreover, these have been expanded further to the 10Rs outlined by Kirchherr et al. [17], which also include refuse, rethink, repair, refurbish, and repurpose. The circular economy can also reuse, repair, and remanufacture products that have been reclaimed from their current users [27,36].

The Elvis & Kresse case study shows that “rescue” can also be a fundamental component of the circular economy and serve as a basis for achieving sustainability. It resembles “recover” in that what would be considered waste is instead used to create further value. However, it differs in that recover would better suit the manufacturing process in creating a feedback loop to reduce waste as much as possible. While Elvis & Kresse do follow a recover approach to reduce the waste output from their own manufacturing processes, the fire-hoses, the core basic resource upon which the whole business model is built, are rescued from landfills and come from another industry with which it has had no association. Based on this starting point for which raw material to use in production, this case study shows that a new business model for a sustainable and social impact, one that is based on the circular economy, can be developed from scratch based on waste from a presumably unrelated industry. In this case, it was fire-hoses discarded by the firefighting sector at one end and the luxury goods sector at the other end. This case study therefore shows that sustainability is not just about improving a part of the supply chain but rather even linking the supply chains of disparate industries. It is also about rethinking the whole notion of luxury products, such that it goes beyond using rare, exotic, and valuable natural materials and relying on short-term seasonal consumption patterns.

4.2. Practical Implications

New strategies for sustainable production and consumption could change the landscape of the fashion industry and the nature of competition [37]. The global fashion industry generates around 53 million tons of fabric each year, and over 70% of this is sent to landfills, with less than 1% being recovered to produce new garments [2]. The fashion industry is acclaimed for being one of the most creative industries, but considering the vast amount of waste it generates, it has become necessary for designers to address this problem by rescuing waste materials and giving them a second life. However, despite the growing noise about the waste in the fashion industry, efforts to confront this issue are still at an early phase. Furthermore, despite the increasing number of solutions, the root problems of over-production and over-consumption remain unaddressed [2].

Over-production leads to excessive inventory, resulting in markdowns that in turn promote over-consumption [38]. As the consumption of clothes increases, the fashion industry’s impacts do as well, making it one of the principal polluters [1]. This issue has arisen in part due to the quick turnaround in new styles that has been driven by competition among large clothing retailers since the 1990s. For instance, the lifecycle of fashion trends and products halved between 1992 and 2002, thus increasing the rate at which clothes are consumed and discarded [1]. The addition of more seasons every year by the fashion industry (e.g., autumn, winter, spring, summer, Halloween, Christmas, Easter, spring break, etc.) and the motivation for retailers to restock more frequently to attract consumers has only exacerbated the problem.

In contrast, Elvis & Kresse opted for the slow fashion production of classical pieces that will last well beyond any single season. If other manufacturers and retailers too adopt such an approach, it could help increase consumers’ awareness of the over-consumption issue, leading to a more sustainable industry. Elvis & Kresse has developed a business model that not only fits with the circular economy but is also purpose-driven, and underpinned by a rescue–transform–donate model. In contrast to the findings of a prior study of sustainability in ten Italian producers of luxury clothes and leather footwear, where the focus was on practices geared toward reducing the negative impacts associated with current operations, the Elvis & Kresse case exemplifies how radical strategies can be used to address root problems by using a material that is completely different to the usual raw leather [39,40].

The firm rescues items that were destined for landfills, where they would take many years to disintegrate and decompose. Instead, it leverages the material’s robust properties to build durable luxury products, with half of the resulting profits donated to charitable causes, thus furthering the sustainability agenda. The company also relies on the goodwill of its customers in supporting such causes. By setting up the fire-hose-rescue project and sustainably and ethically engaging with the problem, Elvis & Kresse is helping to achieve three of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN, namely decent work and economic growth, industry and infrastructure innovation, and responsible consumption and production. Indeed, a greater engagement with the circular economy could help achieve the SDGs by 2030.

While small players such as Elvis & Kresse can prove that something is worthwhile and feasible, fully tackling the environmental waste problem would need a circular economy approach to be adopted not just by niche luxury companies but also leading global players. Such a business model would require reduced consumption of luxury and fashionable goods, because there simply are not enough exotic raw materials available, or for that matter even more common materials such as polyester and cotton [39]. Although Elvis & Kresse found a way to tackle the problem of waste fire-hoses, there remain many other problems to solve. Thus, to reduce the current negative impact of the fashion industry on the environment, more brands need to encourage customers to consume less. By eradicating over-production, removing discounts, and encouraging the selection of sustainable alternatives, a positive impact on the triple bottom line may be gradually achieved [2].

As society’s mindset for consumption habits shifts, especially among younger consumers, brands’ sustainability practices are becoming a major concern when it comes to buying luxury fashion items. Hence, firms should review their processes from top to bottom and take stock of their ecological and social impact on the planet. In the future, sustainability credentials will determine consumers’ brand loyalty [41,42]. Hence, companies should focus on circular business models for their product offerings, as well as circular supply chains and circular customer experiences [42]. Supply chains, for example, could be modified according to real product demand, thus avoiding over-consumption and the controversial practice of destroying excess stock to keep prices high. This wastes finite and precious raw materials [43,44]. Companies can exploit their creativity to reinvent materials, produce new textiles, or repurpose waste to make innovative garments or accessories, as exemplified by Elvis & Kresse.

External factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic can trigger companies and consumers to act. During times of dire need, zero-waste production is more efficient and promotes sustainability. For instance, the plastic waste from 3D printers has been recycled for reuse as raw material for further use in 3D printing operations, as exhibited in the case of manufacturing personal protection equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic [45]. Companies should however also guide and support consumer behavior toward circularity. Consumers could be crucial players in circular fashion, because repairing a single item and extending its lifecycle by at least nine months would help decrease the fashion industry’s carbon emissions by 30% [41]. Thus, new products and circular business models that promote repairing, reselling, and renting items may be incorporated within the operations of luxury fashion firms. New marketplaces and platforms are needed where consumers can rent or buy durable second-hand items [42]. Companies then need to aim to be successful not just only among their consumers but also their employees. A purpose-driven business model gives daily work real meaning and a motivation to innovate, demonstrating that making profits is not the only reason for a company to exist [46].

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

While the strength of this study lies in being a deep exposition of a single innovative case study in the luxury fashion sector, the findings may not be applicable to all companies or sectors. The luxury fashion and fast fashion sectors are increasingly being called upon to do their part for sustainability. But while the approaches outlined here can work well for the luxury sector, it may not be easy to replicate them in fast fashion. Further studies could therefore be conducted to explore similar practices and outcomes for other sectors. Studies could use primary data-collection techniques, such as ethnography, to observe the practices and decision-making challenges of purpose-driven businesses such as Elvis & Kresse in order to enrich and generalize this case study’s conclusions. Studies could empirically assess the extent to which luxury fashion companies incorporate performance-assessment methods for the circular economy [26]. This paper focused on the business model of a manufacturing-intensive company, which suggests that circular manufacturing deserves a particular focus as well [27]. For manufacturing companies, data sharing and information management are crucial to support circular manufacturing particularly for complex products. Consequently, how companies gather and use information about the characteristics of the materials used for circular manufacturing will be important to consider in future research [47,48]. As the company’s products reach end-of-life, research can evaluate the number of optimal times the fire-hose material can be reused. A recent study has developed a model of reuse efficiency taking into account several factors such as product demand, end-of-life collection, durability, and rate of deterioration of material, which may be applied to this and other similar companies [49]. Finally, sustainability can arise from the use of frugal resources in innovative ways [50]. This study of Elvis & Kresse suggests that even though the waste material itself may not cost anything, detailed cost evaluations of the expense and effort of reclaiming and preparing waste to be ready for use as a raw material for new products may reveal that the process may not sometimes be frugal at all.

5. Conclusions

This case study offers lessons for the study and practice of sustainability. For scholars, the case analysis suggests that the traditional business model canvas needs to be revised beyond the current focus on the financial bottom line in order to account for the social and ethical dimensions of business. The responsible business model is one way to do so [23]. For practitioners, the case study demonstrates how the circular economy can work for luxury goods. The purpose of Elvis & Kresse’s business, which embraces the rescue–transform–donate business model, demonstrates that even though the waste issues affecting the environment are not easy to tackle, a meaningful difference can be made by rethinking the value of waste material and redesigning traditional business models. The more the company rescues, the more it transforms, and subsequently the more it donates. Elvis & Kresse has proven that the luxury sector can be successful by moving away from typical luxury value chains that are dependent on the use of rare and exotic materials combined with cheap, globalized supply of resources and labor. As social and environmental concerns grow, more companies could follow suit in aligning luxury fashion with sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su141911805/s1.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this study, from conceptualization to final revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, but the article processing charge for open access was paid for by the MBS College of Business and Entrepreneurship, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This manuscript uses data obtained from the Elvis & Kresse company by securing appropriate permission. The signed consent is uploaded as Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Interviews and podcasts that served as data sources.

Table A1.

Interviews and podcasts that served as data sources.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A2.

Webpages and blogs that served as data sources.

Table A2.

Webpages and blogs that served as data sources.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Cobbing, M.; Vicaire, Y. Timeout for Fast Fashion; Greenpeace: Hamburg, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-international-stateless/2018/01/6c356f9a-fact-sheet-timeout-for-fast-fashion.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- McKinsey & Co. State of Fashion Report. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/state%20of%20fashion/2021/the-state-of-fashion-2021-vf.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Elvis & Kresse. An Interview with Burberry—Kresse Wesling of Elvis & Kresse. Available online: https://www.elvisandkresse.com/blogs/news/interview-burberry-elvis-kresse (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- De Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, H.; Lee, P. An exploratory study of the mechanism of sustainable value creation in the luxury fashion industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, D.; Bassanini, F. Reporting sustainability in China: Evidence from the global powers of luxury goods. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. How Much Do Our Wardrobes Cost to the Environment? Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/09/23/costo-moda-medio-ambiente (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Pencarelli, T.; Ali Taha, V.; Škerháková, V.; Valentiny, T.; Fedorko, R. Luxury Products and Sustainability Issues from the Perspective of Young Italian Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case-based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wang, Y.; Lo, C.; Shum, M. The impact of ethical fashion on consumer purchase behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Etsy, D.; Winston, A. Green to Gold; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Colasante, A.; D’ Adamo, I. The circular economy and bioeconomy in the fashion sector: Emergence of a “sustainability bias”. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croom, S.; Vidal, N.; Spetic, W.; Marshall, D.; McCarthy, L. Impact of social sustainability orientation and supply chain practices on operational performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 2344–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the business models for circular economy—Towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar]

- Zajko, K.; Hojnik, B.B. Social franchising model as a scaling strategy for ICT reuse: A case study of an international franchise. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, M.; Attaelmanan, I.; Imbuldeniya, A.; Harris, M.; Darzi, A.; Bhatti, Y. From Malawi to Middlesex: The case of the Arbutus Drill Cover System as an example of the cost-saving potential of frugal innovations for the UK NHS. BMJ Innov. 2018, 4, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, M.; Tremblay, M.; Audebrand, M. Responsible Business Model Canvas. Université Laval. Available online: https://www4.fsa.ulaval.ca/en/research/educational-leadership-chairs/developpement-esprit-entreprendre-entrepreneuriat/responsible-business-model-canvas/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Urbinati, A.; Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Chiaroni, D.; Terzi, S. Circular business models in the European manufacturing industry: A multiple case study analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Rocca, R.; Terzi, S. Circular Economy performance assessment methods: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Taisch, M. A literature review on circular economy adoption in the manufacturing sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van Buren, N.; Demmers, M.; van der Heijden, R.; Witlox, F. Towards a Circular Economy: The Role of Dutch Logistics Industries and Governments. Sustainability 2016, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certified B Corporation. About B Corps. Available online: https://bcorporation.uk/about-b-corps (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Nidumolu, R.; Prahalad, C.; Rangaswami, M. Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gardetti, M. Sustainable Management of Luxury; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, Z.; Maqbool, A.; Haleem, A.; Pathak, R.D.; Samson, D. Analyzing the business models for circular economy im-plementation: A fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Oper. Manag. Res. 2021, 14, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempels, C.; Hoffmann, J. Sustainable Innovation Strategy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, Y.; Prabhu, J. Frugal Innovation and Social Innovation: Linked Paths to Achieving Inclusion Sustainably, In Handbook of Inclusive Innovation: The Role of Organizations, Markets and Communities in Social Innovation; George, G., Baker, T., Tracey, P., Joshi, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 354–376. [Google Scholar]

- Gorissen, L.; Vrancken, K.; Manshoven, S. Transition Thinking and Business Model Innovation—Towards a Transformative Business Model and New Role for the Reuse Centres of Limburg, Belgium. Sustainability 2016, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Hassi, L. Emerging design strategies in sustainable production and consumption of textiles and clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 13, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L. Fashion marketing. Text. Prog. 2013, 45, 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Granskog, A.; Lobis, M.; Magnus, K. The Future of Sustainable Fashion. McKinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-future-of-sustainable-fashion (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Bittner, M. Is Luxury Resale the Future of Fashion? McKinsey& Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/is-luxury-resale-the-future-of-fashion (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Rothschild, V. For H&M, the Future of Fashion is Both ‘Circular’ and Digital. McKinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/for-h-and-m-the-future-of-fashion-is-both-circular-and-digital (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Dalton, M. Why Luxury Brands Burn Their Own Goods. Wall Street Journal. 6 September 2018, p. 2. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/burning-luxury-goods-goes-out-of-style-at-burberry-1536238351 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Karaosman, H.; Perry, P.; Brun, A.; Morales-Alonso, G. Behind the runway: Extending sustainability in luxury fashion supply chains. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaros, A.; Laskaris, N.; Piromalis, D.; Ganetsos, T. Manufacturing Zero-Waste COVID-19 Personal Protection Equipment: A Case Study of Utilizing 3D Printing While Employing Waste Material Recycling. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameel, F.; Jameel, H.; Schwartz, D.; Youssef, A. How ALJ—A ‘75-Year-Old Start-Up’—Leads with Purpose. McKinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/how-alj-a-75-year-old-start-up-leads-with-purpose (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Acerbi, F.; Sassanelli, C.; Terzi, S.; Taisch, M. A Systematic Literature Review on Data and Information Required for Circular Manufacturing Strategies Adoption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Sassanelli, C.; Taisch, M. A conceptual data model promoting data-driven circular manufacturing. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022; Online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, S. Reuse-efficiency model for evaluating circularity of end-of-life products. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 171, 108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Agarwal, N.; Bhatti, Y.; Levänen, J. Frugal innovation: Antecedents, mediators, and consequences. Create. Innov. Manag. 2022, 31, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).