Challenges toward Sustainability? Experiences and Approaches to Literary Tourism from Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Cultural Tourism

2.2. Literary Geography

2.3. Literary Tourism

“Literary tourism is a subset of cultural tourism and heritage tourism that includes places associated with literature writers, literary books and stories, literary festivals, creative arts, movies, and media productions”[31].

“Literary tourism is an opportunity to travel to the birthplaces, graves, houses, properties, and sites hosting memorabilia and relics of literary figures; such trips provide rich cultural experiences, chances to participate in literary festivals and events, and also opportunities to visualize the space where the creative thinking was formed or the place where famous literary works were created”[37].

3. Methodology

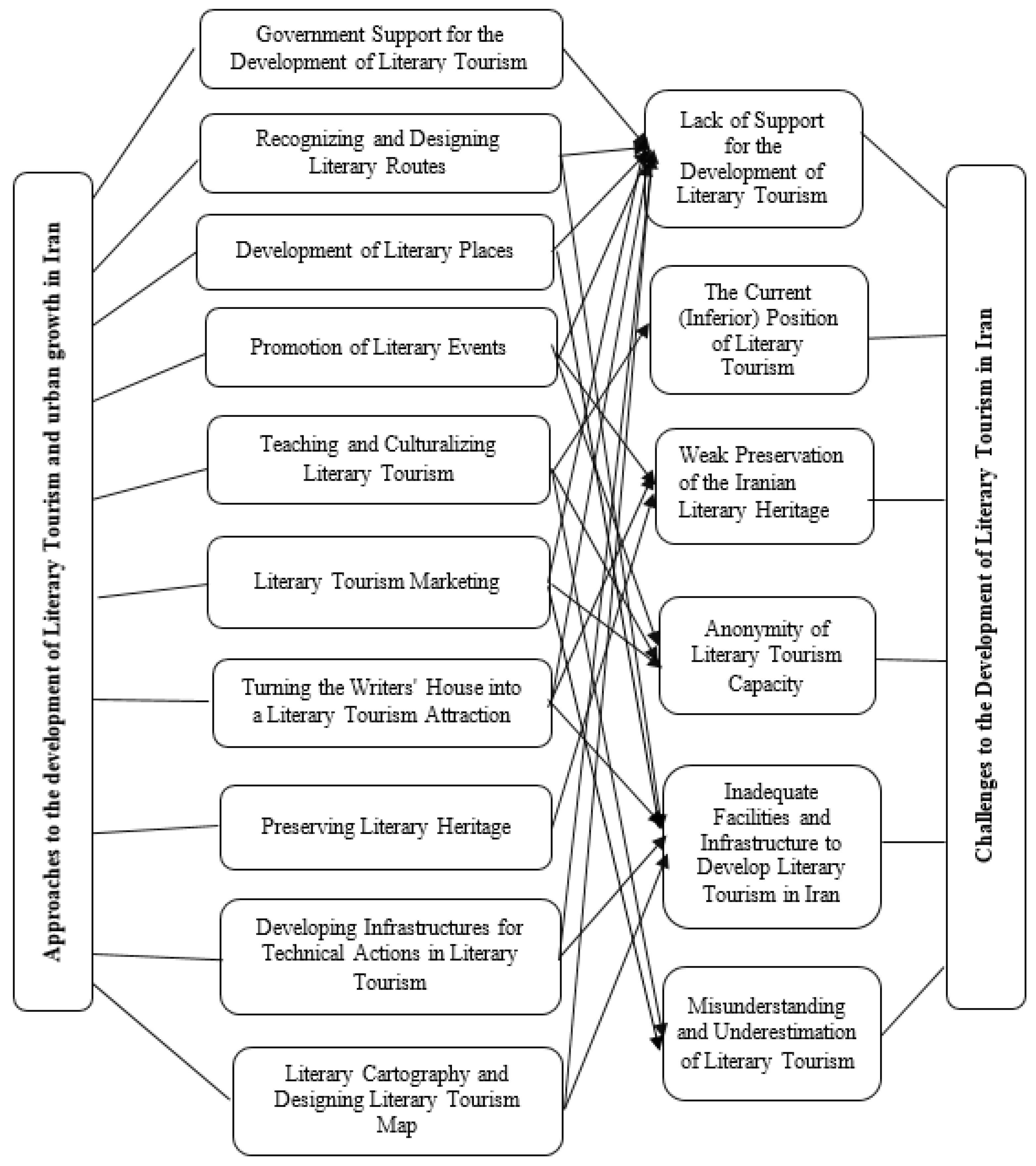

- Lack of Support for the Development of Literary Tourism;

- The Current (Inferior) Position of Literary Tourism;

- Weak Preservation of the Iranian Literary Heritage;

- Anonymity of Literary Tourism Capacities;

- Inadequate Facilities and Infrastructure to Develop Literary Tourism;

- Misunderstanding and Underestimation of Literary Tourism.

- 1.

- Government Support for the Development of Literary Tourism;

- 2.

- Recognizing and Designing Literary Routes;

- 3.

- Development of Literary Places;

- 4.

- Promotion of Literary Events;

- 5.

- Teaching and Culturalizing Literary Tourism;

- 6.

- Literary Tourism Marketing;

- 7.

- Turning the Writers’ House into a Literary Tourism Attraction;

- 8.

- Preserving Literary Heritage;

- 9.

- Developing Infrastructures for Technical Actions in Literary Tourism;

- 10.

- Literary Cartography and Designing Literary Tourism Map.

4. Results

4.1. Developing Literary Tourism in Iran: New and Old Challenges

4.1.1. Lack of Support for the Development of Literary Tourism

“literary tourism in Iran as the cradle of literature has been neglected so far. This failure can have various reasons, but the most important one is the negligence of the officials in using the literary capacities of the country (…). A specific strategy for using these capacities has not been defined (…). Due to the negligence of the officials, who knows where Jalal Al-Ahmad’s house or (…) is and whether is it possible to visit them at all or not”.

4.1.2. The Current (Inferior) Position of Literary Tourism

“(…) Iran can revolutionize the tourism industry with its literary richness and poets such as Saadi, Hafez, Ferdowsi, Khayyam, Attar, and Baba Tahir; but unfortunately, this type of tourism still has no place in Iran and for this reason, Iran is deprived of its income and some of the capacities of this industry are being destroyed” [67]. “Iran despite having plenty of potentials has not been able to properly present itself as a literary tourism hub by introducing Iranian poets and literary figures and benefit from its positive effects”[68].

4.1.3. Weak Preservation of the Iranian Literary Heritage

4.1.4. Anonymity of Literary Tourism Capacities

“due to its mystical literature and ancient culture, Iran is one of the destinations in the world with great potential for the development of literary tourism which has received less attention so far (…). This requires more effective and efficient planning to benefit from this cultural and spiritual heritage. One of the first steps is designing the special path of literary tourism”[70].

4.1.5. Inadequate Facilities and Infrastructure to Develop Literary Tourism

“so far, no comprehensive plan has been developed to direct and organize this type of tourism (…). The anonymity of space-based works is one of the important problems facing the literary tourism of Iran”[27].

4.1.6. Misunderstanding and Underestimation of Literary Tourism

“Literary tourism in its modern notion and concept is not defined in our country and does not have a long history either (…) that we expect it to gain attention in our country like other countries”[71].

“Our literary tourism is limited to visiting the silent graves. If they (people) go to Konya to see Rumi’s tomb, they get acquainted with a collection; there is Mevlevi Sema Ceremony and music, but here everything is limited to one tombstone”[72].

4.2. Approaches to the Development of Literary Tourism and Urban Growth in Iran

4.2.1. Government Support for the Development of Literary Tourism

“bringing together the three vertices of government, industry and academia triangle to cooperate and consult on the ways to develop literary tourism better and more sustainable at the regional, national and local levels”, and “encouraging the government and industry to diversify the country’s tourism product by relying on the country’s valuable literary assets”.

4.2.2. Recognizing and Designing Literary Routes

“literary tourism is a form of cultural tourism that is narrative and creating based on the routes introduced by famous figures. In Iran, it is possible to define tourism routes for each of these poets and philosophers, introduce these routes, and attract tourists in honor of their birthdays and memorials. Of course, defining routes for literary tourism requires doing scientific research, defining basic concepts, and reviving historical identity, and these issues should be considered for the promotion of this form of tourism”[73].

4.2.3. Development of Literary Places

“places that carry the culture and literature of a country with them are the attraction of literary tourism. Literature in Iran is thousands of years old. Thousands of poets, writers, and literates have lived in this land whose houses and tombs can be a meeting place for those interested in literature and tourism”[74].

4.2.4. Promotion of Literary Events

“in literary festivals, such as the celebration of Ferdowsi’s birthday (…) it is necessary to consider aspects of literary tourism in addition to the scientific and literary ones and necessary measures should be taken to expand the sphere of internal influence as well as the sphere of external one at the same time with the literary festival as a literary tourism event”[75].

4.2.5. Teaching and Culturalizing Literary Tourism

“our ancient and contemporary literature is now almost faded in the shadow of the literature of other nations and is ignored by different segments of the country, especially the youth. So, to introduce it to the world and strengthen its position in public, it must be thought of in more attractive, creative, and less elitist ways. One of the methods that has many approaches for society is the connection between the tourism industry and the literary heritage of the country”[76].

4.2.6. Literary Tourism Marketing

“we go to Tus and Neyshabur and visit the tombs of Khayyam, Attar, Ferdowsi, and Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, but the literary tour has its own meaning and concept. It is a complete specialized tour with special audiences and tour guides specialized in literature and poetry”[77].

4.2.7. Turning the Writers’ Houses into a Literary Tourism Attraction

“in our country, despite the existence of successful and brilliant figures in the world of culture and art, almost no serious action has been taken to preserve the houses of (those) artists… The house of Jalal Al-Ahmad’s adolescence (…) can be a good place for those who are enthusiastic about this author and a place to introduce him to Iranian and non-Iranian cultural tourists”[78].

4.2.8. Preserving Literary Heritage

“one of the rich heritage of Iranians (…) is its literature. Literature is a manifestation of creativity and self-confidence (…). Literature in the cultural sphere of Iran due to its richness and undeniable diversity (…) is a treasure that (protection of it) can lead to the promotion of the name of Iran (…). The link tourism industry and literary heritage needs coherent planning”[79].

4.2.9. Developing Infrastructures for Technical Actions in Literary Tourism

“today, the tourist attraction industry is competitive around the world and it is increasingly getting technical. So there is a need for advertising, cultural promoting, and giving information (with a technical approach). Iran, with its deep cultural and literary infrastructure, is largely free from the need to create artificial tourism hubs. However, little importance is given to the country’s abundant assets in this area”.

4.2.10. ‘Literary Cartography’ and Designing Literary Tourism Maps

“the ultimate goal of this project is to design a multi-layered map with research and tourism objectives for all cities of Iran, in which other important components in a literary map such as the birthplace of writers and poets and the place of occurrence of epic narratives have also been considered”(p. 98).

5. Discussion

5.1. Rethinking ‘Literary Tourism’ as the Engine of Tourism Development in Iran

5.2. ‘Literary Tourism’ and Sustainable Tourism Development

5.3. The Methodological Issue: The Power of Narrative Analysis and the Need for Quantitative Surveys

5.4. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Çevik, S. Literary tourism as a field of research over the period 1997–2016. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 24, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liritzis, I.; Korka, E. Archaeometry’s Role in Cultural Heritage Sustainability and Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Thomas, S.; Powell, L. The development of key characteristics of welsh island cultural identity and sustainable tourism in Wales. Sci. Cult. 2017, 3, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghanim, K.; Gardner, A.; El-Menshawy, S. The relation between spaces and cultural change: Supermalls and cultural change in Qatari society. Sci. Cult. 2017, 3, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, C.; Cormack, P. Guarding authenticity at literary tourism sites. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 686–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R. Marin Držić: A case for Croatian literary tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2008, 3, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, J.; Khalili, S.; Khalfi, A. Study of obstacles to the development of the tourism industry in IRI. J. Dev. Evol. Manag. 2010, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, N.; Rastegar, E.; Salvati, L.; Darabi, H.; Fard, N.A.; Taji, M. Motivation-based Market Segmentation in Rural Tourism: The Case of Sámán, Iran. Almatourism J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2019, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bidaki, A.Z.; Hosseini, S.H. Literary tourism as a modern approach for development of tourism in Tajikistan. J. Tour. Hosp. 2014, 3, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Saeedi, A.; Beheshti, S.M.; Rezvani, R. The main obstacles to tourism policy from the point of view of elites. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 1, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi-Farsani, N.; Saffari, B.; Shafiei, Z.; Shafieian, A. Persian literary heritage tourism: Travel agents’ perspectives in Shiraz, Iran. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 13, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabriz Municipality. Submitting the Tabriz Proposal to UNESCO as a Creative City of Literature. 2021. Available online: https://shahryarnews.ir/news/74314 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Shiraz University. Shiraz Proposal Was Submitted to UNESCO for Membership in the Creative Cities of Literature. 2019. Available online: https://shirazu.ac.ir/en (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Bell, D.; Oakley, K. Cultural Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, I.; Lund, K.A. Literary Tourism: Theories, Practice and Case Studies; CABI: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anjo, A.M.; Sousa, B.; Santos, V.; Lopes Dias, Á.; Valeri, M. Lisbon as a literary tourism site: Εssays of a digital map of Pessoa as a new trigger. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2021, 7, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, H.-C.; Robinson, M. Literature and Tourism, Reading and Writing Tourism Texts; Continuum: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, A.C.; Pereira, E. Live your readings–Literary tourism as a revitalization of knowledge through leisure. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2021, 35, 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, B. Literary tourism: Constructions of value, celebrity and distinction. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2008, 11, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, S. Cultural tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 212–213. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stiebel, L. Going on (literary) pilgrimage: Constructing the Rider Haggard literary trail. Scrut. Issues Engl. Stud. S. Afr. 2007, 12, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, D. Literary places, tourism and the heritage experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Cros, H.; McKercher, B. Cultural Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, H.I. Mark Twain’s Homes and Literary Tourism; University of Missouri Press: Columbia, MO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seyed Ghasem, L.; Nooh Pisheh, H. Literary Geography and its branches: Introduction of new interdisciplinary studies in the literature. Lit. Crit. 2016, 9, 11–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tally, R. Spatiality; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H. The construction of literary tourism site. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2009, 57, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Yu, L. Consumption of a literary tourism place: A perspective of embodiment. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppen, A.; Brown, L.; Fyall, A. Literary tourism: Opportunities and challenges for the marketing and branding of destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, N.; Shelley, J.; Morrison, A.M. The touring reader: Understanding the bibliophile’s experience of literary tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, N.; Hayes, D.; Slater, A. Reading the Landscape: The Development of a Typology of Literary Trails that Incorporate an Experiential Design Perspective. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannakis, J.N.; Davies, A. Diversifying rural economies through literary tourism: A review of literary tourism in Western Australia. J. Herit. Tour. 2012, 7, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.J. The Literary Tourist: Readers and Places in Romantic and Victorian Britain; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ommundsen, W. If It Is Tuesday, This Is Must Be Jane Austen’s: Literary Tourism and the Heritage Industry. 2014. Available online: http://www.textjournal.com.au (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Topler, P.T. Literary tourism as a successful practice implementing sustainable tourism in Slovenia. In Proceedings of the Third International Scientific Conference, Belgrade, Serbia, 8 June 2017; pp. 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; MacLeod, N.; Hart Robertson, M. Key Concepts in Tourist Studies; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, D.K. Unplanned Development of Literary Tourism in Two Municipalities in Rural Sweden. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 6, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Salvati, L.; Gemmiti, R.; Perini, L. Land degradation in Mediterranean urban areas: An unexplored link with planning? Area 2012, 44, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, R.; Brunori, E.; Smiraglia, D.; Salvati, L. Linking traditional tree-crop landscapes and agro-biodiversity in Central Italy using a database of typical and traditional products: A multiple risk assessment through a data mining analysis. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 3009–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelleri, L.; Schuetze, T.; Salvati, L. Integrating resilience with urban sustainability in neglected neighborhoods: Challenges and opportunities of transitioning to decentralized water management in Mexico City. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckett, A.G. Applying thematic analysis theory to practice: A researcher’s experience. Contemp. Nurse 2005, 19, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M.P.; Ding, G. Geo-narrative: Extending geographic information systems for narrative analysis in qualitative and mixed-method research. Prof. Geogr. 2008, 60, 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvernoy, I.; Zambon, I.; Sateriano, A.; Salvati, L. Pictures from the other side of the fringe: Urban growth and peri-urban agriculture in a post-industrial city (Toulouse, France). J. Rural Stud. 2018, 57, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, C.; Nougarèdes, B.; Sini, L.; Branduini, P.; Salvati, L. Governance changes in peri-urban farmland protection following decentralisation: A comparison between Montpellier (France) and Rome (Italy). Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, M.; Zambon, I.; Pontrandolfi, A.; Turco, R.; Colantoni, A.; Mavrakis, A.; Salvati, L. Urban sprawl and the ‘olive’ landscape: Sustainable land management for ‘crisis’ cities. Geo J. 2019, 84, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, J.A.; Gubrium, J.F. Varieties of Narrative Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mertova, P.; Webster, L. Using Narrative Inquiry as a Research Method: An Introduction to Critical Event Narrative Analysis in Research, Teaching and Professional Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Quinteiro, S.; Carreira, V.; Gonçalves, A.R. Coimbra as a literary tourism destination: Landscapes of literature. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 14, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nes, F.; Abma, T.; Jonsson, H.; Deeg, D. Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? Eur. J. Ageing 2010, 7, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, S.J. The cultural values of literary tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, S.J. Literary tourism and sustainable tourism: Promoting’ Anne of Green Gables’ in Prince Edward Island. J. Sustain. Tour. 1996, 4, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, J. Qualitative Analysis for Planning & Policy: Beyond the Numbers; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Y. From the Grand Tour to African adventure: Haggard-inspired literary tourism. S. Afr. J. Cult. Hist. 2013, 27, 132–156. [Google Scholar]

- Otay Demir, F.; Yavuz Görkem, Ş.; Rafferty, G. An inquiry on the potential of computational literary techniques towards successful destination branding and literary tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 764–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, G. Literary tourism: Brazilian literature through anglophone lenses. Transl. Stud. 2018, 11, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feely, M. Assemblage analysis: An experimental new-materialist method for analysing narrative data. Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.V. Analysing and representing narrative data: The long and winding road. Curr. Narrat. 2010, 1, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, C. A comparison of inductive and deductive approaches to teaching foreign languages. Mod. Lang. J. 1989, 73, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.A. The inductive-deductive controversy revisited. Mod. Lang. J. 1979, 63, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomamizadeh, E. Bad Fortune for Iranian Literary Tourism. 2015. Available online: http://www.donyayesafar.com/n/1394/06/25 (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Zare, H. Neglecting Literary Tourism in the Capital of Iranian Poetry and Literature. 2016. Available online: https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1395/07/14 (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Siamian Gorji, A. Literary Tourism. 2012. Available online: http://tourismscience.blogfa.com/category/1391/10/04 (accessed on 24 December 2012).

- Javan Online. Houses of Literary Figures Are Going Downhill. 2012. Available online: http://www.javanonline.ir/fa/news/1391/05/24 (accessed on 14 August 2012).

- Farahani, F. Designing the Route of Literary Tourism and Its Impact on the Economy of Iran. 2014. Available online: http://b2bnet.info/1395/12/08 (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Golbu, F. Literary Tourism Is Not Reduced to a Tombstone. 2014. Available online: https://www.mehrnews.com/news/2377434 (accessed on 27 September 2014).

- Aslani, M. News Interview: International Tourism Day. 2014. Available online: http://www.mehrnews.com/news/1393/07/05 (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Hekmatnia. A Passenger Named “Saadi” in the Heart of Literary Tourism. 2016. Available online: https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1395/01/31 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Shams, F.; Literary Tourism. On Shoulders of Persian Poets. World of Economy Newspaper, No. 3081. 2013. Available online: http://donya-e-eqtesad.com/news/770752/1392/09/14 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Saghaei, M. Literary Tourism and Ferdowsi’s. 2014. Available online: http://shahraraonline.com/news/40300/1393/02/25 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Noor Aghaei, A. Introduction to the National Conference on Literary Tourism. 2012. Available online: http://www.literarytourism.ir/1391/10/02 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Noor Aghaei, A. There is no Concern for Designing a Literary Tour/We are not Familiar with Our Myths. 2015. Available online: http://www.toptourism.ir/1393/12/08 (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Mortezaeifard, Z. The Dust of Oblivion on the House of Jalal. 2016. Available online: http://jamejamonline.ir/online/2570394250668240981/1395/07/15 (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Soroush Moghadam, S. The Link between Tourism and Literary Heritage. 2014. Available online: http://www.hamedanpayam.com/56446/1393/12/04 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Mehrvarz, T. Identifying the Capacities of Literary Tourism in Gilan Province. Master’s Thesis, University of Gilan, Gilan Studies Research Institute, Gilan, Iran, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, P.; Vera, A.; Tulla, A.F.; Salvati, L. Beyond urban–rural dichotomy: Exploring socioeconomic and land-use processes of change in Spain (1991–2011). Appl. Geogr. 2014, 55, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontos, K.; Syrmali, M.E.; Vavouras, I.; Karagkouni, E.; Saradakou, E.; Salvati, L. Tourism in time of crisis: Specialization, spatial diversification and potential to growth across European regions. Tourismos 2017, 12, 176–200. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, R.; Chelli, F.M.; Ciommi, M.; Musella, G.; Punzo, G.; Salvati, L. Trahit sua quemque voluptas. The multidimensional satisfaction of foreign tourists visiting Italy. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 70, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiebel, L. Hitting the hot spots: Literary tourism as a research field with particular reference to KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Crit. Arts 2004, 18, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari Chianeh, R.; Del Chiappa, G.; Ghasemi, V. Cultural and religious tourism development in Iran: Prospects and challenges. Anatolia 2018, 29, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, P.M.; Novelli, M. Tourism Development: Growth, Myths, and Inequalities; CABI: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Khodadadi, M. Challenges and opportunities for tourism development in Iran: Perspectives of Iranian tourism suppliers. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C. Tourist trap: Re-branding history and the commodification of the South in literary tourism in Mississippi. Stud. Pop. Cult. 2013, 36, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.J.; Zhang, D. Comparing literary tourism in mainland China and Taiwan: The Lu Xun native place and the Lin Yutang house. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakabati, Y. Deterrents to tourism development in Iran. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, I.; Ferrara, A.; Salvia, R.; Mosconi, E.M.; Fici, L.; Turco, R.; Salvati, L. Rural districts between urbanization and land abandonment: Undermining long-term changes in Mediterranean landscapes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Ciuraneta, S.; Durà-Guimerà, A.; Salvati, L. Not only tourism: Unravelling suburbanization, second-home expansion and “rural” sprawl in Catalonia, Spain. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Farahani, H.; Musa, G. Residents’ attitudes and perception towards tourism development: A case study of Masooleh, Iran. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1233–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Carlucci, M. The economic and environmental performances of rural districts in Italy: Are competitiveness and sustainability compatible targets? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 2446–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gay, A.; Andújar-Llosa, A.; Salvati, L. Residential mobility, gentrification and neighborhood change in Spanish cities: A post-crisis perspective. Spat. Demogr. 2020, 8, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L. ‘Rural’ sprawl, Mykonian style: A scaling paradox. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 20, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, Y.; Saaty, T.L. Marketing applications of the analytic hierarchy process. Manag. Sci. 1980, 26, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. J. Math. Psychol. 1977, 15, 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.A.; Lamata, M.T. Consistency in the analytic hierarchy process: A new approach. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl.-Based Syst. 2006, 14, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, D.; Vasile, V.; Popa, M.A.; Cristea, A.; Bunduchi, E.; Sigmirean, C.; Ciucan-Rusu, L. Trademark potential increase and entrepreneurship rural development: A case study of Southern Transylvania, Romania. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridolfi, E.; Pujol, D.S.; Ippolito, A.; Saradakou, E.; Salvati, L. An urban political ecology approach to local development in fast-growing, tourism-specialized coastal cities. Tourismos 2017, 12, 166–198. [Google Scholar]

- Salvati, L.; Carlucci, M. A composite index of sustainable development at the local scale: Italy as a case study. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 43, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C. Researching Literary Tourism; Shadows: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-Pumarola, J.; Marzal, E.O.; Llonch-Molina, N. Revealing the literary landscape: Research lines and challenges of literary tourism studies. Enl. Tour. Pathmaking J. 2020, 10, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xu, H. Aesthetic consumption in literary tourism: A case study of Liangshan. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asadi, A.; Bayat, N.; Zanganeh Shahraki, S.; Ahmadifard, N.; Poponi, S.; Salvati, L. Challenges toward Sustainability? Experiences and Approaches to Literary Tourism from Iran. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811709

Asadi A, Bayat N, Zanganeh Shahraki S, Ahmadifard N, Poponi S, Salvati L. Challenges toward Sustainability? Experiences and Approaches to Literary Tourism from Iran. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811709

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsadi, Alireza, Naser Bayat, Saeed Zanganeh Shahraki, Narges Ahmadifard, Stefano Poponi, and Luca Salvati. 2022. "Challenges toward Sustainability? Experiences and Approaches to Literary Tourism from Iran" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811709

APA StyleAsadi, A., Bayat, N., Zanganeh Shahraki, S., Ahmadifard, N., Poponi, S., & Salvati, L. (2022). Challenges toward Sustainability? Experiences and Approaches to Literary Tourism from Iran. Sustainability, 14(18), 11709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811709