Abstract

A sustainable food system is a key target of the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The current global food system operates on market mechanisms that prioritise profit maximisation. This paper examines how small food businesses grow and develop within grassroot economies that operate on different market mechanisms. Focusing on artisan food producers and farmers’ markets, this research highlights the potential of resilient, small-scale, diverse markets as pathways to sustainable food systems. An applied critical realist, mixed-methods study was conducted at a macro (Irish food industry), meso (farmers’ markets in the region of Munster, Ireland) and micro (artisan food producers and their businesses) level. The resulting framework provides a post-growth perspective to sustainability, proposing that farmers’ markets represent an alternative market structure to the dominant industrial market, organised on mechanisms where producers ‘Mind what they make’ and ‘Make peace with enough’. In their resilience, these markets can provide pathways for structural change. This implies a call to action to reorientate policies targeting small food businesses to move beyond the concept of firms as profit-maximizing enterprises and to instead focus on a local food policy framework that reinforces the regional ‘interstices’ within which small food businesses operate to promote diversity, resilience and sustainability in the food system.

1. Introduction

The current food system is a complex and interconnected global web, largely structured on economies-of-scale, comparative advantage, specialisation and profit-maximisation [1,2,3,4,5]. It is generally built upon industrialised agricultural systems [6], concentrated and centralised supply chains [4,5], large-scale food processing firms and a consolidated marketplace of supermarket chains [5]. Food production has been cited as having the greatest ecological impact and is considered the greatest source of environmental degradation [7]. To continue on this trajectory is to move beyond our planetary boundaries [8]. An environmentally sustainable approach to the way we eat is needed [7]. The EU Farm-to-Fork Strategy aims to align the European food system with the 17 global SDGs to become a climate neutral union by 2050 [9]. Our current food system has been cited as a dysfunctional system that falls short of serving both planetary and human health [7]. A transition to a sustainable food system is important; however, the path to this could be broadly seen as split in two. In one direction, we see a technological, global perspective of capital intensification, increased specialisation and vertical integration of the supply chain, with the aim of feeding a growing population with affordable food in a sustainable way [7,8,9,10]. The other path takes a more localised, regional perspective toward food sovereignty, agro-ecology and shortening food supply chains, with the aim of achieving resilience and sustainability through re-localising the food system and emancipating it from industrial market mechanisms [1,2,3,4,5,6,11,12].

A bibliographic and literature review revealed that the most relevant current research gaps in this field include (1) the lack of studies on short food supply chains (SFSCs) in general, especially in the light of the global COVID-19 pandemic and the need for farmers to be closer to consumers; (2) how such supply chains co-exist and collaborate with conventional food chains; and (3) the perspectives of small-scale farmers participating in SFSCs [13,14]. More closely, it was identified that there was a need to study the different actors involved in SFSCs, their actual habits and behaviours, and the motivations that draw farmers towards SFSCs, as well as to apply diverse mid-level theories of the firm to investigate these supply chains [13,15,16]. This current study undertook research that contributes to closing the mentioned gaps through taking the perspective of small-scale artisan food producers operating at one of the unique (and, paradoxically, long-standing) forms of the relatively “newly coined” SFSCs that are underexplored in the literature: farmers’ markets (FMs). While there are many different structures in which SFSCs can operate (e.g., on-farm sale, internet deliveries, box delivery schemes, ‘pick your own’ and community-supported agriculture), traditional FMs, where producers and consumers exchange knowledge and interact, are found in many European countries such as Ireland, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Italy, Greece and many others. We bring novelty by exploring the actual behaviours of small-scale producers at 25 Irish FMs, uncovering different mechanisms that keep them operating at those FMs and by applying Penrose’s theory of firm growth to SFSCs. Thus, this study helps to push forward our current understanding of what happens, and why it happens at FMs and re-imagines the theory of firm growth, focusing on small-scale producers. Our contribution to the body of knowledge on SFSCs stems from providing supporting evidence for the essential role that FMs play in ensuring sustainability in global food systems and assisting small-scale artisan food producers in a post-growth era. In addition, we suggest recommendations for advancing future food policies with an emphasis on acknowledging the part that small-scale producers have in sustainability and incorporating their interests when creating better and more sustainable global food systems.

This study adopts a critical realism (CR) philosophical approach. A CR framework moves from manifest phenomena at the empirical level to identifying generative mechanisms beneath [17], where theory, though fallible, can deepen our ontological understanding of SFSCs [18] and the agency of participants in developing a business within this context [17,18]. The advantage of a CR framework is its usefulness in developing a research design that places agents (artisan food producers) within their context (both FMs and the wider context of the global food system) and through a process of retroduction seeks to uncover and explain the phenomenon under study without conflating agency with structure, thus deepening our understanding of the phenomenon and the possibility of more-targeted policy support [18,19]. Only a few studies in the SFSCs literature have taken this multi-level approach [13,20], with a tendency to focus more on normative practices of facilitating SFSCs [4,5,6,21] or assessing their sustainability [22,23,24]. A disadvantage is the conceptual complexity of CR, which is argued to impact its empirical practicality, and plausible explanation is developed based on a specific theoretical premise [25,26]. However, despite these drawbacks, the CR application of firm level theory to SFSCs creates new knowledge in the SFSC literature and addresses a gap [13] by examining these firms and reimagining firm growth for a post-growth era.

1.1. Background to the Research

Short food supply chains align with a post-growth perspective to sustainability that propounds concepts of sufficiency [27], sustainable prosperity [28], frugal abundance and open re-localisation [29]. Schumacher [27] described this as ‘small is beautiful’, where small-scale, decentralised economies are conceptualised as more resilient and have less impact on the natural environment than large-scale corporations. Although SFSCs are ideologically positioned in opposition, with the aim to reorientate the industrialised food system, in reality, national food strategies work to integrate both paths. The EU Farm-to-Fork Strategy, for example, takes a global technological perspective, while aspects also aim to strengthen the legislative framework of geographical indicators and reduce dependence on long-haul transportation [9]. SFSCs have co-existed alongside and within the conventional system for decades [21,30], where they represent a small percentage of the market share. Previous research has questioned whether SFSCs have the agency to transform the structures of the industrial food system they are embedded within and to bring about the structural change that a post-growth paradigm calls for [2,22].

The industrial food system was developed to meet the consumer demands of an urbanising population [5,10] and has undoubtedly increased food output [22]. The constant drive of economic market mechanisms toward efficiencies and scale have made access to markets and the ability to earn a livelihood for smallholders and micro-food businesses difficult [4]. This, in turn, has threatened the way of life of traditional small-scale food producers, but in some cases, has caused a re-evaluation of the role and identity of food producers in the minds of contemporary society, leading even to protests to protect producers’ interests in terms of minimum guaranteed prices and rights to continue with their traditional production methods (for example, see references [31,32]). Increased market concentration and consolidation has resulted in the loss of agricultural and local food producing jobs [6,11]. These jobs offer more than economic benefits and are ‘pillars’ to rural society, offering social and cultural values [11], and so these losses feed a further migratory flow to urban areas [10]. Urbanisation and the corresponding increase in income and changes in work organisation and family structures naturally lengthens the food-supply-chain, creating distance from agricultural production to food consumption [5]. Contemporary shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Brexit, the war in Ukraine and the increase in extreme-weather events have exposed vulnerabilities in the economic, social and environmental sustainability of these long food supply chains.

Farmers’ markets (FMs) provide market access and livelihoods for local small-scale producers [4,5,23,33,34]. Weber and his colleague described the emergence of alternative markets as dependent on three conditions: (1) like-minded entrepreneurial producers that are motivated and connected, (2) a producer community that constructs external boundaries and (3) adoption of market exchange value for their products [35] (p. 554). In this way, FMs are repositories of practices that form a collective identity, in opposition to the dominant forces of mass production [20,36]. They are presented as markets of ‘morally embedded economic exchange’ [33] (p. 288). Here, the food producers are embedded within their local community and engaged in relational aspects of co-production with customers and collaborations with competitors [35,36]. FMs create regional networks that provide a market rationale for the continued use of small-scale, traditional technologies [37]. However, FMs are vulnerable to economic market mechanisms that position them as niche, high-end products, providing an alternative for the affluent customer who can afford it [33,34] and, as a consequence, gentrifying neighbourhoods [34]. Although FMs’ environmental credentials have been questioned [24,33], they have grown in popularity, driven by consumer demand for sustainability within the food system [4,23,38,39].

This increase in demand for FMs creates further susceptibility to dominant market forces [40]. An example of this is the organic food movement that was set up as an alternative to industrialised food production to promote natural food consumption. The organic food market grew in popularity and thus profitability as large food retailers became interested. This growth resulted in national organic standards, competition and consolidation of organic producers, which resulted in the industrialisation of organic food production [41]. Penrose, in her The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, would describe this as ‘interstices’ or market niches that attract large corporations, where they then dominate, and the temporary ‘interstices’ are absorbed into the larger economy [42]. The prevailing perceptions of firm growth equated with success and industrial production systems can erode these ‘interstices’. From a post-growth perspective, there is a gap in our in-depth understanding of small artisan food producers’ position, and hence, it is worthy to examine the mechanisms that counter the industrialisation trend and instead promote the heterogeneity and value of small-scale artisanal production.

1.2. Theoretical Framework: Small Firm Growth and the ‘Interstices’

Currently, there exist systemic pressures to grow and scale a business [43,44]. The prevailing assumption in the small-firm growth literature is that a business grows when the external market opportunities are right and the internal firm resources are available [42,45]. Yet, the concept of small firm growth is heterogenous and multi-dimensional [46], with a tendency toward conflating micro-firms and self-employment with high-growth ventures [47]. Theory favours the latter, thus promoting economies-of-scale. Micro-enterprises are the backbone of many economies, but there is little understanding of how these micro-enterprises grow and develop [45,47]. Additionally, scaling up these enterprises can adversely affect their local communities [48] and their potential contribution to more resilient, decentralised economies [49,50]. Thus, if FMs are to contribute to food system sustainability, it is valid to examine them through the lens of firm growth theory to understand the idiosyncrasies of developing a business in these ‘interstices’ and post-growth.

Penrose’s The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, first published in 1959, is still considered a seminal theory that integrates the different factors contributing to firm growth over time [42,51]. Her theory encapsulates concepts that explore both inside the firm through the internal resources (the ‘productive opportunity set’/latent resources) and the external environment (market ‘interstices’), mediated by the entrepreneur’s ‘image’ of the marketplace [42]. We argue that a return to and a re-reading (or re-imagining) of Penrose’s theory can provide insight into small firm growth that aligns with a post-growth paradigm. Noting, in particular, her observations of managers during her case study of a large chemical company, from which her eminent The Theory of the Growth of the Firm developed, she commented they were ‘product-minded, reasonably venturesome and imaginative, but concentrating on “workmanship” and product development rather than on expansion for its own sake or for quick profits’ [52] (p. 40). Emphasising this ‘workmanship’ or a craft aspect can shift firm growth from an increase in size to an emphasis of growth as an improvement in quality as the result of a process of development [42]. This craft aspect provides a converse logic to the zealous search for efficiencies within the current industrialised food system.

Penrose, whose focus was on the growth of large firms, saw small firms as occupying niches or ‘interstices’. She described these as windows of opportunity within the structures of the economy, where small firms can exploit the residual productive opportunities left by larger firms, albeit these are vulnerable to the decisions of these large firms. Rather than leftover spaces in the marketplace, from a post-growth perspective, we view these ‘interstices’ as worthy spaces for further interrogation, particularly those niches that promote a different market logic: a ‘more-than-capital’ logic [50,53]. These small firms residing within resilient ‘interstices’ can challenge the dominant industrialised complex, providing alternative ways of doing business and providing a path to a post-growth economy [28]. The challenge to addressing a sustainable food system is daunting, especially a vision that challenges a capitalist paradigm, but by researching the markets that are taking on that challenge, insights can be gained on the mechanisms that keep these diverse economies going [50,53].

We re-examine Penrose’s theory, which is considered the foundation of the firm growth literature, by putting the small artisan producer in the context of FMs at the centre of interest. This paper examines small firm growth within these grassroot economies to understand how they endure and therefore contribute to more resilient, small-scale, decentralised and sustainable food systems. The overall objective of the paper is to provide the perspective and voice of artisan food producers on how they grow and develop their businesses at FMs in Munster, Ireland. We build on what diverse, grassroot economies can contribute to our imagining of a sustainable food system at the business level [35,49,50]. We draw on an applied critical realism (CR) framework [17,25] to illuminate the inherent tensions in artisan food production contrasted with the dominant economic market logic of efficiencies and scale. This study involved a regional, multi-level study at a macro (the Irish food industry), meso (farmers’ markets) and micro (the artisan food producer and their business) level. The resulting framework impacts policy to support local, regional markets that in turn provide a livelihood for the self-employed, micro-firm and promote small, diverse economies, short food supply chains and rural development for a more resilient, sustainable food system.

2. Materials and Methods

This research utilised an applied critical realist methodology [17,18,25,26,54,55,56,57]. Critical realism (CR) views the world as comprised of entities that possess inherent or potential powers (mechanisms) [54]. CR is a depth ontology, which is stratified into interrelated domains of the real, actual and empirical. An implication of this stratification is the use of multiple data sources and methods [26]—an attitude of being ‘maximally inclusive’ when collecting data [54]. Full ethical approval for this research study was received from the Social Research Ethics Committee in the third level education institution within which the authors reside.

2.1. The Research Context: Munster, Ireland

The empirical research is set in Munster, a province in southwest Ireland with a population of approximately 1.2 million people and an area of 24,675 km2. These specific spatial boundaries facilitated a contextualised, multi-level design. Munster is often portrayed as the food capital of Ireland [58]. It has a mix of urban/rural and private/public farmers’ markets (FMs): approximately 83 markets (no formal database exists) of various forms from seasonal to full-time, loosely governed by a set of voluntary guidelines developed by the Irish Food Board (Bord Bia, Dublin, Ireland).

Ireland has a rich food heritage, with a history of markets dating back to the 18th century, where market towns would have fish, milk, potato, and corn markets out on the open streets. In the late 18th century, a covered food market at the centre of a town was considered a sign of a prosperous and expanding city [59]. The industry evolved from subsistence agriculture in the 1950s to its ‘modernisation’ in the 1970s with membership to the EU and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) [60]. Currently, Ireland, as a small, open economy, has an internationally competitive, export-oriented agri-food sector and a vision to become a global leader in sustainable food systems driven by innovation and technology [60]. The latest Irish food strategy, Food Vision 2030 [60], recognises the need to grow a bio-diverse, carbon sequestering horticulture sector (currently representing 1% of land use, the lowest in Europe [58]), encourage rural regeneration and incorporate short food supply chains. However, the focus of this strategy is to grow Ireland’s grass-based livestock production for export, where its role in the global value chain remains the priority [60] (p. 20). This export-focused specialisation builds on Ireland’s comparative advantage, with 81% of farmed land devoted to grass (silage, hay and pasture) for cattle [58]. However, due to the biogenic methane emissions from these ruminants, Ireland’s ambition to become a global leader in sustainability and to be climate neutral by 2050 may fall short [61]. In addition, this strategic focus affects land use by rendering other endeavours, such as tillage and horticulture, as uneconomical [58]. Ireland currently imports a high proportion of cereals, vegetables and fruit that are consumed nationally, despite being able to grow a wide variety of these domestically [62,63,64]. The need for a local food policy is recognised by other countries: for example, the Scottish Parliament recently passed the Good Food Nation Bill to link government, local authorities and health boards to encourage local food procurement and the use of in-season produce. This is on foot of the UK National Food Strategy 2022 that aims to boost production in their domestic horticulture sector. Organisations in Ireland, such as The Cork Food Policy Council, have been formed to advocate for a local food policy [58] that is integrated within the national strategy to support small-scale, local food producers who sell directly into local markets [62,63] as opposed to placing them as alternative market niches [5].

2.2. Data Collection and Research Parameters

All data were collected concurrently within a ten-month period (February to November 2021). The empirical data encompassed face-to-face quantitative surveys (88 artisan food producers from 25 FMs), field observations and informal conversations conducted during the survey collection (41,197 transcribed words) and semi-structured interviews with key field informants (10 experts; 55,288 transcribed words). The secondary data included three Government of Ireland National Food Strategy Documents spanning from 2020 to 2030. Table A1 details the type, purpose and analysis of data conducted at the macro, meso and micro levels of the research.

The intention is not to generalise from an empirical population, but to understand a specific phenomenon for a given population for which purposive sampling techniques were utilised [65]. All FMs that fulfilled the following research criteria were visited: (1) primarily a food market where stallholders are primary or secondary producers, (2) in operation for a minimum of three years, (3) held at a minimum weekly throughout the year, and (4) located in the Munster area. The producers operating a stall at these markets were screened, and those corresponding to the following research criteria were surveyed: (1) engaged in food production that is not fully mechanised (2) in which raw ingredients are processed into prepared food products for consumption elsewhere, and (3) in business for a minimum of three years (considered to have overcome their liability of newness). This homogenous sample aligns with small firm growth research, where like is compared with like [46].

The surveys were conducted with artisan producers face-to-face (an online form administered via a computer tablet) at their stall in the FM (except four surveys that were completed online) while they were serving and interacting with customers, taking an average of twenty-seven minutes to complete, and in some cases up to an hour. The survey captured demographic information, firm resources, previous firm growth, planned future growth, reasons for operating at a FM, satisfaction with their current business and their perception of business growth.

The markets visited ranged from urban supermarket carparks (8 public markets) to town centres (11 public markets) and open streets (6 public markets). Many artisan producers (59 participants sold at more than one market) travelled the Munster region selling at the markets that were not held on consecutive days. Breads (n = 29), confectionaries (n = 31) and condiments, such as homemade jams and preserves (n = 30), were the main products produced by the participants. Table 1 details the profile of survey participants.

Table 1.

General characteristics of survey respondents, n = 88.

In general, the questions stimulated reflections and stories from participants of their everyday business. These field observations and informal conversations were noted when the participant was busy with customers or directly afterwards. The notes were anonymised and linked with the corresponding participant survey number to synthesise the different types of data for each participant (the survey numbers ranged from #13–#100). This ethnographic aspect facilitated a deeper understanding of participants’ aspirations and everyday struggles within the contextual field they operate in.

Interviews were conducted with identified key field informants (10 interviews) purposively sampled for their professional expertise in the area of artisan food and/or FMs. Table A2 details the key informants’ roles and data collected.

2.3. Analytic Strategy

In keeping with applied CR, qualitative analyses (intensive data) of the field observations, informal conversations and interview transcripts were given priority, seeking out demi-regularities through CR thematic analysis of why small artisan food producers remained at FMs [57]. The surveys (extensive data) helped to confirm or deny the identified patterns and to give further insight into the structural relations of the field and agentic practices of small artisan food producers through descriptive analysis [17]. The documentary analysis informed an understanding of the structures at the macro level, within which policies, enterprise support agencies and other entities are embedded. The chosen documents were imported in their entirety into NVivo and were coded with reference to small firm growth, artisan food/small food business, sustainability, farmers’ markets and short food supply chains. The context and chronology of the documents were examined to provide a historical aspect of the development of culture over time [55].

Reflexive thematic analysis [65,66] and specific CR thematic analysis [57] methods were drawn on to analyse the qualitative datasets (field observations, informal conversations and interview transcripts). Three phases of coding and theme development were undertaken in NVivo (version 1.5.2). Seventy-one codes developed through several rounds, which involved a retroductive analytical strategy that moved beyond the constellations of practices and experiences at the empirical level to identify mechanisms that are activated or inhibited at the domain of the real [55,67]. The survey data consisted of nominal and ordinal scale data. Descriptive analysis and two-step cluster analysis was conducted using the SPSS software programme (version 28.0.0.0). Cluster analysis was undertaken to group cases on three categorical variables, pre-set to cluster into four categories to distinguish venture types of small artisan food producers at FMs and to facilitate examination of small firm growth within the homogeneity of each group [46]. The three variables chosen formed a meaningful typology: business structure indicated administrative responsibility and formality of the business; the production unit variable represented resources available to the business; and the self-selected category required reflection on their identity as business owners [68].

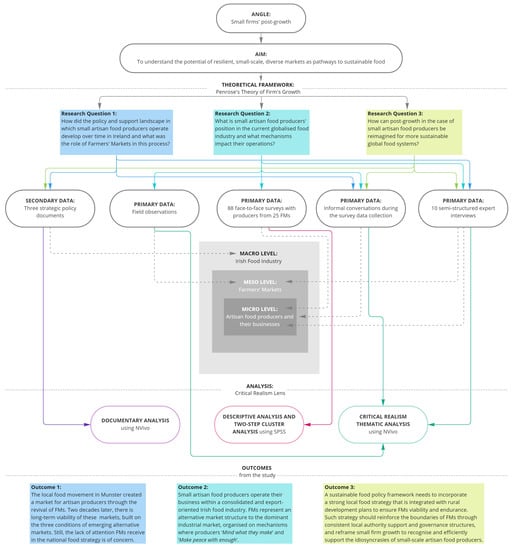

All data were considered and integrated, and are presented in the following section as one coherent piece to capture the interrelationship between contextual structures, the agency of small artisan food producers, the enactment of generative mechanisms and the resulting emergent social phenomena of operating at FMs. The different sources of data represent the complex, contextual and relational world from a CR perspective [17,25,67]. Figure 1 summarises the study’s design and shows the relationship between the main aim, theoretical framework, research questions, data collection, levels of analysis, and study outcomes.

Figure 1.

The study’s research design.

3. Results

3.1. Documentary Analysis and Cluster Analysis of Small Artisan Food Producers

The documentary analysis of the three national food strategies (Food Harvest 2020 [69], Food Wise 2025 [70] and Food Vision 2030 [60]) demonstrated the evolution of how artisan food and farmers’ markets are framed within policy and their diminishing significance. Food Harvest 2020 highlighted the potential of the sector to enrich tourism, regional growth and employment creation, describing artisan food as a ‘significant sector’ [69] (p. 9). Subsequently, Food Wise 2025 dedicated a section of the strategy, with specific action points, to artisan and small food businesses [70] (p. 87), recognising the significant impact they have on local economies and local farms. Finally, Food Vision 2030 mentions artisans in the goal to ‘increase primary producer diversification and resilience’ [60] (p. 116) and mentions FMs as short-supply-chains that play a role in growing the horticulture sector in balance with Ireland’s role in the global value chain. An identified issue in all food strategies is the limited size of Ireland’s domestic market, which creates difficulties in scaling a business and results in international targets. An example of this is the focus of the Bord Bia strategy to create a premium ‘Food Brand Ireland’ driven by Origin Green (Ireland’s pioneering food and drink programme for sustainability) as an umbrella, cross-sectoral brand on the world stage [71] (p. 47). As a result, FMs are framed as ‘springboards’ to the supermarket shelf and as ‘incubation units for start-up food and drink businesses’ [70] (p. 87). In contrast, Ireland’s rural development policy, Our Rural Future 2021–2025 [72] recognises the need to support, within the broader entrepreneurial ecosystem, the micro and social businesses that fill the needs in the market, particularly in rural areas, that are not attractive to commercial, profit-driven businesses, rather than encouraging these businesses to grow on the national and international stage (p. 21). This growth-critical perspective was illustrated further by the survey data, showing that most businesses had been established for at least six years (76%), owners did not plan to expand their business (73%), and the majority of participants considered FMs as a long-term and sustainable path to market (88%).

The FMs visited were evidently embedded within an industrialised food system. Supermarkets were places to procure ingredients, and the more-lucrative FMs were private markets set up in supermarket carparks. The heterogeneity of businesses operating at FMs and their endeavours to incorporate economic, social and environment aspects of their business are highlighted in the four clusters, presented in Table 2 below. Artisan food is considered a highly fragmented niche in Ireland [70]—a sub-classification of these businesses does not currently exist. The survey data showed that 64% of all participants produced their products in a rural location, yet only 13% of all participants classified themselves as full-time farmers. Cluster analysis presented the ‘on farm production’ cluster (representing all participants that operated from a production unit on the farm) as the smallest cluster, representing 18% of all participants; they also represented the highest income (69% earning over €200,000 per annum). Participants in this cluster primarily produced meat and dairy products (52%), were the least-dependent on FMs for their turnover (50% received 1–20% of their turnover from FMs) and were more nationally than regionally focused (44% supplied nationally). In contrast, the ‘domestic-oriented self-employed’ cluster was the largest group, representing 35% of overall respondents. This cluster had a less-formal structure, lower turnover (65% earned less than €50,000 turnover per annum), were more focused on serving their local market (51% serve one county or less), and FMs were their main path to market, which embedded them within FMs more than the other clusters. The ‘commercial oriented entrepreneurs’ were more structured and growth-oriented (65% not satisfied with size of business) and were also focused on the service sector and independent shops as other paths to market. The ‘commercial oriented artisan’ cluster also operated out of commercial kitchens but were less structured (76% were sole-traders or partnership) and were more focused on bakery and confectionary products (64%). ‘On farm production’ and ‘domestic oriented self-employed’ were most satisfied with their size of business, although 31% of the ‘on farm production’ cluster planned to reduce business size in the future. The main motivation to be at FMs for ‘domestic oriented self-employed’ and ‘commercial oriented entrepreneur’ clusters was to be their own boss; for the ‘on farm production’ cluster, it was passion for food (75%) and to be part of a local food system (69%); and for ‘commercial oriented artisan’, it was to be part of a community (81%) and to build relationships (81%).

Table 2.

Presentation of cluster analysis results of survey respondents 1.

Food Vision 2030 points to the challenge of social sustainability for primary producers in Ireland and the issue of gender balance in this sector [60]. There is potential to increase the ‘on farm production’ cluster and the overall representation of farmers at FMs. In addition, the survey presented an overall gender balance of males (57%) and females (43%), indicating that FMs engage both male and female artisan food producers. Further, the place-based context of FMs and the artisan producers on them provide potential to increase Irish food provenance and further engage with EU quality schemes, such as the geographical indicators (GI) that promote and protect quality agricultural products and foods. A goal of Food Vision 2030 is to increase Ireland’s GIs (currently only 7, compared to Italy with almost 300 product types registered [60]).

Further examination of the structures within the FMs demonstrated an alternative logic to the industrialised food system: one structured on social capital revealing this alternative entrepreneurial ecosystem. For example, there were cases where producers collaborated with each other to co-create a community structured of co-production (e.g., an Irish cheese producer located next to the Israeli falafel stall collaborated to create a halloumi product), bartering (e.g., a sausage producer used the kitchens of other stall owners in return for doing some work for them), shared resources (e.g., shared delivery of products organically occurred amongst producers in a rural area) and generosity (e.g., a producer allowed the new bakery to use their kitchens at night when they were not in use to ‘get them on their feet’). This illustrates alternative, grassroot markets that align with a post-growth logic, emphasising craft, local economies and convivial communities. This co-production mechanism structured the context of the FMs at the meso-level. An examination of the individual agency of the artisan producers and their business at the micro level revealed further mechanisms, as discussed in the following sections.

3.2. The Emergence and Endurance of ‘Interstices’

The modern-day establishment of FMs began in Ireland as a grassroots movement in the early 1990s in a bid to keep small farmers on their land and provide low-cost access to markets for disparate small food producers, as Rolf reminisced when he began smoking fish almost 40 years ago.

“You see there was no market for the food we made, we had to create a market […]. So, for us as small producers, we all started independently without any contact with each other, and Mrs. Allen pulled it all together. She said look there are all these cheese people, and fish mongers, and whatever, and it was all pulled together, and that creates a dynamic”.(Rolf, artisan fish smoker, #46)

This ‘pulling together’ of producers and connecting with consumers to co-create an alternate economy was enhanced by a key enduring legal entity, the Casual Trading Act 1995, that allowed public markets to take place. Further to this, in 2008, a Farmers’ Market Forum was organised by the Irish Minister for Food and Horticulture to form a common approach across government departments, agencies and local authorities to promote and strengthen the viability and prosperity of the FM system in Ireland [73]. This was the first of its kind in Ireland, and there has been no subsequent forum on FMs since. The Allen family have been prominent artisan food advocates in Munster since the 1960s, and were key to the resurgence of FMs and the re-activation of this act. Dan, an artisan baker at FMs for 30 years, credits these individuals:

“The first thing is she [Darina Allen] is the one, she fights for butchers who slaughter their own, she fights for artisans, who make black and white pudding, not the ones who use dried blood, but the ones who use fresh blood, which is very, very difficult. And free-range chicken producers, free range egg producers. All of these small high-quality people whom the health inspectors are crushing, or at that stage were crushing”.(Dan, artisan baker, #52)

These agents that ‘fight’ against ‘crushing’ external forces, whether perceived or real, to maintain an alternative market that supports their small-scale, local craft production are key entities, instigators and ‘guardians’ of the markets. Further evidence of these ‘guardians’, maintaining the culture and ‘symbolic boundaries’, was an informal conversation with a fish monger at a market, who referred to a salami producer as “24 years battling the health boards, he is a legend”. These ‘guardians’ co-ordinated to petition the government and ensure markets would not be shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdowns. There is an informal recognition of these roles, as Marcus (condiment producer, #57) pointed out in a conversation at his stall: “You see I think everyone is standing on everyone else’s shoulders here”.

There exists a support infrastructure for food businesses in Ireland, consisting mainly of soft support, such as guides to starting a food business, food law and food marketing, developed by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland: Bord Bia and Teagasc (the Irish Agriculture and Food Development Authority). The regional enterprise boards (local enterprise offices) provide mentoring, workshops and financial support to help specific businesses (those engaged in manufacturing or internationally traded services and employing fewer than 10 people) start-up and grow, through micro-finance loans (from €2000 to €25,000) as well as feasibility (maximum €15,000) start-up and business expansion (both not to exceed 50% of the investment) grants. A national initiative targeted specifically to small artisan food producers is the Food Academy Programme established in 2013 and run by Bord Bia, the local enterprise offices, and SuperValu (an Irish supermarket chain). The programme provides workshops, one-to-one mentoring and supermarket shelf space to successful participants. This provides opportunity to artisans to bring their product on to the supermarket shelf and for the stores to meet the increase in consumer demand for local and artisanal products. As Brian (food consultant working with small food businesses, #7) noted in his interview, “the retailers will give what the market wants, and the market wants local food, so they are reacting to that”. This demand can leave the producers vulnerable to economic market logic. However, an oppositional narrative was created that Brian termed “urban legends”, which was a pattern found across the informal conversations and an ‘entity’ that rationalised the logic of operating on the FM.

“There is a lot of urban legends about not getting paid, they will stiff you and drive over you rough shot. But that is not true, those days are gone that might have been 40 years ago, but not now. The large retailers are very good to deal with and are very supportive of artisan producers and they want them on their shelves, and they do pay them on time”.(Brian, food consultant working with small food businesses, #7)

This narrative extended for many participants to emancipating themselves from financial institutions and enterprise agencies and thus the perceived pressure to grow their business. ‘Minding what you make’ was a generative mechanism that furthered this resistance to growth. As one participant (meal producer, informal conversation, #31) explained “Enterprise Boards want you to buy the big machinery, you could very easily get into big debt and go under. Where are they then? You are left on your own to shoulder it. They only know growth”.

3.3. Mechanism: ‘Minding What You Make’

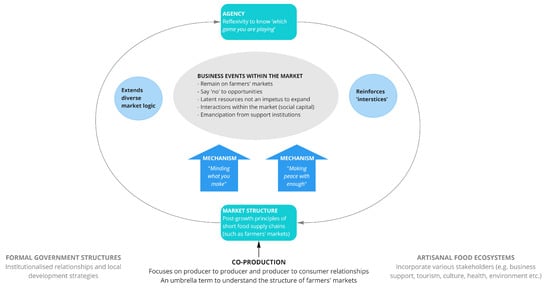

Two underlying mechanisms were identified through the critical realist analysis of field observation, survey responses and interviews that provide an explanation as to why these small-scale artisan food producers remain at FMs rather than chasing efficiencies and scale on the supermarket shelf. These were ‘Minding what you make’ and ‘Making peace with enough’, which enabled producers to say “no” to market opportunities and resist the impetus to expand through latent resources. On a subjective level, the reflexivity to know which game producers are playing reinforced the post-growth ‘interstices’ they operated within. This created a reinforcing cycle, presented in Figure 2, where individual reflexive agency further embedded the producer within the market, enabling the two mechanisms to further generate the structure of the market, creating a logic for their small-scale, localised, craft production as an alternative to the industrialised food system.

Figure 2.

Framework of the reinforcing cycle of farmers’ markets (FMs) as resilient ‘interstices’.

This perspective of small artisan food producers is further presented through the lens of small firm growth theory. In particular, we took the multiple levels of Penrose’s theory, from her concept of the ‘interstices’, the internal resources of the firm and the subjectivity of the producer to further unravel how the two identified mechanisms reinforce FMs as resilient ‘interstices’.

The ‘Minding what you make’ mechanism underlays many instances. For example, it was important customers received their products fresh, resulting in small batch production, and cooking and storage instructions were often given as part of the transaction at the market stall. Rolf illustrates this further:

“All that matters is people getting the same satisfaction from the enjoyment of what we make, that is fundamental and the rest of it is irrelevant, as far as I am concerned […]. It is about minding what you make, caring for your customer […] minding the people that support us, and we mind the people we supply. That is the game”.(Rolf, artisan fish smoker, #46)

This mechanism affected business decisions and perception of market opportunities. In some instances, it was observed that producers gave their products away for free if they were not happy with the quality or if they struggled to charge a higher price. One participant noted, “maybe I’m not mercenary enough and that is the problem, but I don’t want to charge too much for my products. I don’t want only the rich eating them. I wouldn’t be comfortable with that” (producer of salads and meals, informal conversation, #89). Saying “no” to market opportunities in order to mind the production processes meant many producers remained at the FM. A small-holding dairy farmer with six years in business described it as follows:

“Very few people handmake raw butter. There is a huge demand for it that we would never be able to satisfy. It is about making peace with that and recognising the way we think, is that every opportunity needs to be exploited. But we would be run off our feet and then we would lose what we do. It is hard to say no though”.(Dairy farmer, informal conversation, #81)

Easier routes to market exist, such as online farmers’ market platforms, which Tracy (FM consultant, #6) felt would threaten FMs. However, most participants did not use the platform (68%), and some that used it mentioned that it either complicated their business, eroded their margins, made them lose some connection with customers, or they had concerns with logistics. A further mechanism ‘Making peace with enough’ that can contribute toward explaining why producers remain at the market and are not growing on to the supermarket shelf is outlined next.

3.4. Mechanism: ‘Making Peace with Enough’

Maintaining lifestyle and time for family life was integrated into business decisions, as a participant who spent seven years at the FM (Israeli falafel maker, informal conversation, #58) discussed: “I take my time not putting myself under pressure”. This is possible because of the close relationship with customers, and hence producers are able to explain when they do not have products. One participant with five years in business (jam maker, informal conversation, #35) highlighted: “If I had to supply a shop, I’d have to be up all-night making products”. Kathy, who set up a FM in 1996 and who has seen many traders come and go, commented:

“You see really, you see it is all connected with sustainability. Are people satisfied to earn x amount and say I am so happy, I have got a good lifestyle, but I am only earning just this much. Or do they always have to be driving to be bigger and to be better and have more income, and far more outlay, and probably have the same amount. […] It is the kudos of having a bigger building or having the restaurant. I think it is the kudos. That is why people move on [from FMs]. They think they are going up a scale really”.(Kathy, FM founder and manager, #1)

Similarly, Tracy (FM consultant, #6) noted the importance of reflexivity to “knowing how big you want to get and know what it is that makes you happy”. A tendency was identified within the data to ‘Know which game you are playing’, represented at the top of Figure 1 leading to the downward arrow of reinforcing the ‘interstices’. FMs, although aligned with a post-growth paradigm, are entangled within an economic market logic. This meant that the participants needed to reflect on what market logic they resided in for the identified mechanisms to be enabled.

The economic market logic of efficiencies and scale facilitate lower prices on the supermarket shelf, which positions FMs, particularly in urban areas, as premium and upmarket. However, this was not the experience of some producers on the FMs, as one participant noted:

“We are being told that food at markets and artisan food is high-end, but really this is the traditional food, this is the real food that we used to always eat. It is now being put forward in this way as a differentiation to the cheap food we buy in the supermarket”.(condiment producer, informal conversation, #94)

The struggle and hard work involved with small-scale production was evident, as one female food producer who sold her condiments for eight years at the market described it, “I am doing everything myself, it is too much, I need to grow my well-being” (condiment producer, informal conversation, #89). Another illustration was a female food producer, 13 years at the FMs, who exclaimed, “I’m still operating hand to mouth and in order for it to be sustainable I feel I need to grow it [the business]” (condiment producer, informal conversation, #54). Tracy said about her own experience when asked about the pressures of growing a business, “It is a wonderful freeing thing to say no actually small is gorgeous” (FM consultant, #6).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

A sustainable food system needs to balance profitability and livelihoods (economic sustainability) with broad-based benefits to society (social sustainability) and a positive or at least neutral impact on nature (environmental sustainability) [9]. To achieve this, the UN SDGs, the EU Green Deal and Ireland’s current national food strategy recognise the need for diversity within the food system. If Ireland is to become a global leader in sustainable food systems, a detailed local food policy that promotes the domestic horticulture sector, gender balance in the agricultural sector and rural regeneration is needed [61,62,63]. Within this context, this article highlighted the perspectives of small artisan food producers who operate their businesses at farmers’ markets (FMs) within a consolidated and export-oriented Irish food industry. It was found that FMs represent small-scale, decentralised markets for food producers—‘interstices’ structured by post-growth characteristics that support the local economy, create social value and are seen to someway reduce environmental externalities of the transportation and industrial food imports associated with a global food system [4,23,38]. The logic of the two mechanisms identified (‘Minding what you make’ and ‘Making peace with enough’) highlights that FMs have been adopting and promoting sustainable practices (partly due to market constraints and partly due to the mindset of the producers) since the early 1990s, when they were (re)established in Ireland. The role small artisan food producers and FMs play in the food industry was identified in the earlier national food strategies [69,70] with the establishment of the FM forum in 2008 [73] and within the current rural development plan [72]. However, the lack of organisation of any further FM forums and the lack of attention for FMs in the current national food strategy is of concern.

The FMs were structured around the mechanism of co-production, which happens when individuals not in the same organization contribute to the production of a good or a service [74,75]. This was evidenced by the efforts between different producers, and also between the producers and consumers—these dynamics and interactions created the market. Co-production as a concept can be considered an umbrella term that contributes, in this case, to understanding the structure of FMs, in which their social engagement builds trust and embeds customers within the food chain, but it can also be argued as lacking nuance to explain the phenomenon fully [75]. However, while there are other mechanisms beyond co-production (such as Formal Government Structures and Artisanal Food Ecosystems), the key advantages of the co-production concept compared to the other mechanisms is its suitability (it helps us to understand a market structure—FMs) and its focus on producer-to-producer and producer-to-consumer relationships. From a critical realist (CR) perspective, the reflexive agent’s interaction with this co-production mechanism can either reproduce or transform this structure. The endurance of these FMs is dependent on the reinforcing cycle, depicted in Figure 2, whereby their structures are continually reproduced through the collective agency of the participants. The local food movement in Munster created a market for artisan producers through the revival of FMs. Two decades later, this study found the long-term viability of these markets and their co-production structure is extended through the food producers’ agency and business development, which builds on the three conditions of emerging alternative markets developed by Weber and colleagues [35]. An extension of these three conditions has compounded the culture and structure of these ‘interstices’ to endure:

- The connection and inter-relationship of like-minded producers, further emphasised by the reflexivity to ‘Know which game you are playing’;

- External boundaries of the producer market, further enforced through symbolic boundaries such as ‘guardians of the market’ and narratives such as ‘urban legends’, to ensure the structures of the market are protected to enable the mechanisms ‘Minding what you make’ and ‘Making peace with enough’;

- Establishing fair market exchange value for their products that encompasses valuing social and environmental values.

Supporting these three conditions requires a re-imagining of Penrose’s seminal theory of firm growth, as well as shifting our collective understanding of what growth can mean in a sustainable global society, to reinforce the ‘interstices’ that emancipate these businesses from systemic pressures to grow. The emphasis should instead be on FMs’ sustainability, which is becoming increasing relevant for the food industry, yet it is perhaps overlooked in the case of these alternative markets, which, for decades, have been advocating small-scale, local craft and rural livelihoods. Rather than conceptualising these market niches as temporary windows of opportunity for small businesses, this research reframes Penrose’s ‘interstices’ as pathways to structural change toward a post-growth economy with an emphasis on sustainability. This builds further on the contribution that diverse, grassroot economies can make to post-growth research at the business level [35,49].

Additionally, a post-growth perspective of Penrose’s theory calls for reframing of her concept of latent firm resources as an impetus to expansion. Penrose developed her theory in the 1950s, an industrial age of macro-economic expansion where external limits were not considered [76]. Yet, it continues to remain the underlying assumption that when external market opportunities and internal firm resources exist, firm growth occurs [44]. An example of integrating Penrose’s theory within a circular economy model is supermarkets’ deteriorating fruit and vegetables, which can become a latent resource for artisan food producers to add value to and to sell directly to customers at FMs [77].

Small firm growth research is critical in the advice it gives policymakers and business owners, which can create systemic pressures to grow and scale a business [43,44]. From a CR perspective, explanatory theory expounds that when an entity is in place, a mechanism happens, but when empirical evidence contradicts this, plausible explanations are sought as to why this mechanism (firm growth) is inhibited [17]. In this research, the empirical data illuminated the mechanism ‘Making peace with enough’, which shifted the focus from maximising latent firm resources to balancing business with other values, such as lifestyle, family and wellbeing and emphasising the need to move beyond solely economic measurements of growth [28,53,78]. In some instances, this mechanism involved saying “no” to market opportunities, thus inhibiting firm growth. We also found the mechanism ‘Minding what you make’ emphasised the workmanship aspect of Penrose’s theory, for which growth becomes a qualitative process of development. This resulted in small artisan food producers becoming more resourceful to emancipate themselves from financial institutions and support structures that were seen to encourage firm growth, consistent with the previous literature [76]. However, the results also demonstrated the dependence on key individuals, ‘guardians of the market’, to protect and support FMs, which further identifies a need for targeted support in this area that moves beyond the economic growth paradigm.

This current study found that farmers’ motivations to join and remain at FMs were generally based on perceived social, economic and lifestyle factors. Similar observations have been made in other studies. One study in Hungary found that farmers who were more open to co-operation had specific investment plans for their farm development, and the ones who were looking to directly interact with their customers to avoid middlemen had stronger preferences for FMs compared to conventional markets, for which the relationship would be defined by binding contracts [79]. A case study of newly developed FMs in three low-income urban areas in Michigan revealed that farmers joined because they saw them as a primary livelihood strategy, a new business opportunity, recreation or a social mission [80]. Another study revealed that willingness to participate in SFSCs was affected by farmers’ competences in management, entrepreneurship, marketing, networking and co-operation, meaning that farmers’ competences significantly affected their involvement in SFSCs [81]. Thus, food policies should address this by supporting farmers in achieving more competences in the mentioned areas. It was also noted that different small-scale farmers will likely benefit from different supporting frameworks, interventions and initiatives [79], which corroborates our findings in the cluster analysis, where different cluster categories had different views about what growth meant for them in terms of the economic, social and environmental aspects of their business.

Previous literature found regionally embedded, growth-critical firms important to decentralized, regional economies [49], with the potential to contribute to flourishing communities [28] through more meaningful work and social relationships [27]. Local food markets with a wish to transform the industrial food system through short food supply chains [22,23,24,38] can also become contradictions and result in commodifying local food [3]. The ethnographic aspect of this research found that exchange value extended beyond the product to the market stall, the set-up, and the banter with customers and fellow traders. These interactions, the co-production structure and the culture of the market feed the flow of social capital beyond economic transactions [53]. However, these markets can become idealised through their potential, rather than the hybrids they are in practice, enmeshed and entangled within the global food system. FMs can be one of a few paths to market for food producers [82] as they struggle to earn a livelihood. Cluster analysis revealed varying types of small artisan food producers within this regional study, encompassing sole-traders, artisans, entrepreneurs and farmers (see Table 2). Those producers that transverse the two different market logics tended to perceive a fundamental flaw in their business, similar to the struggle and conflict experienced when there is a misfit between entrepreneurial identity and their type of business [68,82]. The reflexivity to ‘Know which game you are playing’ was a contingent condition necessary to keep artisan producers small-scale and local within a resilient market of practice and toward what could be described as a more ‘sustainable prosperity’ [28] of ‘Making peace with enough’, aligned with Schumacher’s philosophy of ‘enoughness’ [27]. This facilitated the endurance of these markets to resist the pull of the industrialised food system and remain as short food supply chains (SFSCs) with a sustainability focus, although it was a struggle to earn a livelihood. Similarities can be drawn with a Mexican study that found that organic farmers who operated at a dedicated organic FM faced increased labour requirements for organic products, lack of organic certification schemes, and issues with storage, transportation and the attraction of more consumers [83], all of which confirm the hardships that producers endure staying and surviving at a FM.

Nevertheless, FMs were found to have an important role to play in supporting sustainable local food systems in Ireland. Other studies have also recognised the importance of FMs for sustainability. For example, in the case of an SFSC in Brazil, it was found that organic street-market characteristics can contribute to more-sustainable supply chains [84]. A study done in Czechia and Ukraine highlighted that FMs are important signals of sustainable consumption, and that relevant marketing strategies should include an emphasis on social relationships with food, such as the role of farmers, markets, food festivals and alike, which can promote healthy eating [85]. Another study from Australia argued that FMs promote conscious consumption, provide support for local businesses and produce, enhance cultural and gastronomic heritage and, as a by-product of their contribution to the sustainability of the local food systems where they operate, FMs have the potential to offer authentic, social activities that support more-sustainable forms of tourism (e.g., proximity and slow tourism) [86]. Interestingly, a comparative study of metropolitan FMs in Minneapolis and Vienna found that they had different purposes, missions or goals: FMs in Vienna served mostly as spaces for everyday food shopping, while FMs in Minneapolis were mission-oriented and exhibited values related to environmental and social concerns and broader awareness of food and farming issues [87]. This suggests that a stronger, focused sense of values and mission promoted at each FM could potentially bring even more benefits to sustainable SFSCs.

An additional value of the FMs for sustainability was reflected in mentioned mutually beneficial interactions and exchanges between producers and consumers, which was noted in the current study and was consistent with other similar studies. For example, a study in Romania found that through FMs, consumers gained access to local products at a lower cost and learned how their products were made at the so-called piaţa, while farmers retained some profit by elimination of wholesalers and achieved increased interaction and customer loyalty [88]. Moreover, in the USA, evidence shows that FMs provide a platform where farmers can educate consumers on agroecological techniques used, and in turn receive feedback through consumers’ purchasing behaviour [89], which can help to better align food demand and supply. By incorporating trust elements and emotional relationships, FMs can increase consumers’ purchase intentions [90] and contribute to more sustainable and healthier food consumption.

It is evident that the global industrialised food system needs to transform to a sustainable food system. In ecological thought, diversity breeds resilience [50], which highlights the importance of supporting diverse markets such as FMs. However, policy and theory can side-line these ‘everyday’ micro businesses in favour of entrepreneurial ventures defined by their propensity to grow, such as the ‘Silicon Valley’ business model [47]. Research has shown that SFSCs foster local food production, reconnect consumers with the producers of their food, create regional, diversified economies and promote rural regeneration [4,5,6,23]. They represent a path to food sovereignty and a sustainable food system in Ireland that should not be ignored, with potential to be the backbone of local food, an integral part of the economy and to contribute to Ireland’s identity [82] (p. 2). As a precondition for greater justice and sustainability, the right of people to define their agri-food systems should be an integral part of reimagining small firms’ post-growth era, and small artisan food producers have an important role to play in the quest to re-politicise food [91]. The potential of an FM system is illustrated in Paris, with over 70 FMs and 5000 traders operating in the city, supported by over 30% of the Paris population and where local authorities provide all services (stalls, electricity, water and cleaning) [73]. A sustainable food policy framework in Ireland and other countries needs to incorporate a strong local food strategy that is integrated with rural development plans to ensure FM viability and endurance. Such a strategy should work in two main ways: firstly, to reinforce the boundaries of FMs through consistent local authority support and governance structures, and secondly, to reframe small firm growth for small artisan food producers to recognise and efficiently support the idiosyncrasies of such producers; for example, in a way, this research identified two unique mechanisms (‘Making peace with enough’ and ‘Minding what you make’) as a starting point. In addition, various action plans should particularly focus on the importance of sustainable food farms for people in rural and urban areas in an environmental, social and economic sense, as well as apply participatory development approaches and work towards ensuring socio–environmental justice, including sustainable food and access to food outlets such as FMs [92].

In the future, it is likely that some rural resources and lands, for example less-favoured areas that have the potential for alternative development (a good example is the former mining area outlined in [93]), as well as the idea of agri-food entrepreneurship, will become increasingly interesting to various domestic and foreign investors. While such investments are welcome, they might shift the patterns of ownership and control over agricultural resources, influence farmland values and affect rural communities [94]. For example, in the case of the Canadian and Australian grain sectors, it was found that farmland and agricultural investment schemes faced many challenges: from the lack of willingness of domestic capital to invest in the country’s agricultural sector, to concerns about ‘land grabs’, prompting governments to scrutinise purchases and tighten ownership rules [95]. It will be of great importance to ensure through policy mechanisms that any domestic or foreign investment in the agri-food sector, and especially in SFSCs such as FMs, protects the interests and autonomy of small artisan food producers in Ireland and enhances their sustainability.

Digitalisation of small-scale artisan food producers’ business operations was addressed in this study through questions on the usage and perceived benefits and threats of an online FM platform. While it was found that most participants did not use an online platform, digitalisation of SFSCs is nevertheless an important component that needs to be accounted for in new food policies to ensure sustainability for food producers. AI and digitalisation show great potential to assist in the transition towards a sustainable food system, but farmers are considered the weakest link in the farm-to-fork data space, especially as some of the key barriers to digitalisation and exchange of technological knowledge in rural areas are socio–cultural ones related to an aging and sparse population [96,97]. To build a sustainable global food system, SFSCs need to become more adaptable, flexible, resilient and traceable, and FMs should not be neglected in this restructuring process [98]. Hence, food policies need to envisage a space for FM digitalisation and account for accompanying data use, access and rights, support farmers’ digital literacy and adaptive capacities, and consider global data commons databases that will allow meaningful innovation and avoid information asymmetries [99]. In addition, support in areas such as website and social media marketing, and readily available market intelligence, sales analytics with real-time data and sales forecasting to efficiently co-ordinate production and demand while also reducing food waste [77,100] could offer immediate benefits to small-scale producers.

In conclusion, a local food policy has the potential to increase the ‘on farm production’ cluster identified in this research, support Ireland’s domestic horticulture sector and emphasise the social sustainability of primary producers, identified by Food Vision 2030 as an often overlooked dimension of sustainability [60] (p. 11). Penrose’s theory has informed firm growth for over fifty years—now is the time to revise small firm growth within the context of sustainability to incorporate social and environmental values.

Regarding limitations, this research focused on a specific geographic location within a specific industry at a specific time, consciously examining the producers’ perspective as opposed to other stakeholders. The exploratory findings are contingent on context. Theoretical leanings toward a post-growth narrative also play a role in the account. Given a theory-laden epistemology and a theory-independent ontology, other plausible explanations of firm growth for the small artisan food producer are possible based on other theoretical redescriptions. However, the mechanisms identified and the developed framework provide a starting point for further research on sustainable food systems at the business level. Application of the framework in other regions and communities would inform interesting comparative research. Further in-depth longitudinal research into the situated micro-processes and practices of small artisan food producers and their businesses in short food supply chains would inform more nuanced local food policies and provide deeper detail of post-growth structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.C., J.B. and L.R.; methodology, R.C., J.B. and L.R.; software, R.C.; validation, R.C.; formal analysis, R.C.; investigation, R.C.; resources, R.C., J.B. and L.R.; data curation, R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C., J.B. and L.R.; visualisation, R.C. and L.R.; supervision, J.B. and L.R.; project administration, J.B. and L.R.; funding acquisition, R.C., J.B and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Irish Research Council, grant number GOIPG/2020/1305.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the UCC Code of Research Conduct and approved by the Social Research Ethics Committee of University College Cork, Ireland (Log 2020-167 and approval 22 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will not be made available at this point in time since the research is still ongoing and because this study is part of a bigger project with an end date in late 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Data sources at multiple levels: purpose, type and analysis conducted.

Table A1.

Data sources at multiple levels: purpose, type and analysis conducted.

| Level | Purpose | Types of Data | Data Collected | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macro | Provides context to position FMs as ‘interstices’ within the structures of the Irish food system | Irish government strategies and farmers’ market documents | 3 National Food Strategies: Food Harvest 2020: published 2010 [69] Food Wise 2025: published 2015 [70] Food Vision 2030: published 2020 [60] Irish Government Strategy: Our Rural Future: published 2021 [72] Irish Food Board Strategy: Nurturing a Thriving Future: published 2022 [71] 3 Farmers’ Market documents: Local Authority Forum on Farmers’: published 2008 [73] Guide to Food Markets in Ireland: published 2013 [82] Village Market Handbook: published 2012 [101] | Full documents imported into NVivo (version 1.5.2). Content analysis and themes developed around small firm growth, artisan food, FMs and short food supply chains and sustainability. |

| Key field informant interviews | Enterprise Support Officers (3), Food Consultants (2), FM manager (1), FM consultant (1), Market insurance broker (1) Total: 8 Interviews, 37,940 words | CR thematic analysis of interview transcripts in NVivo. | ||

| Meso | The structure of relations between individuals in the field. Surveys were based around their motivation to be at FMs and their previous growth and planned future business growth. | Face-to-face survey questions were demographically based, tick-all-that-apply options, 5-point Likert scale and open-ended questions | 88 participants—25 FMs | Descriptive analysis in SPSS (version 28.0.0.0). Simple frequencies are examined, and central tendencies are detected through the mode; two-step cluster analysis. |

| These interviews were with 2 small artisan food producers that have stalls at Cork markets since their (re)establishment in the early 1990s. Termed ‘Master Artisan’ due to their long tenure. | ‘Master Artisan’ experts identified by their long tenure and dedication to FMs | 2 interviews, 17,348 words | CR thematic analysis of interview transcripts in NVivo. | |

| Micro | Small artisan food producers’ perceptions and ‘image’ of the marketplace, past and present experiences. | Field observations and informal conversations | 25 FMs visited, 33,900 words | CR thematic analysis of field notes in NVivo. |

| Recorded informal conversations with AFEs | 5 artisan producers, 7297 words | CR thematic analysis of interview transcripts NVivo |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Research participants, name, role and data collected.

Table A2.

Research participants, name, role and data collected.

| Surveys with Informal Conversations (Not Audio Recorded) and Field Observations | Gender | Role | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants #13–#100 (88 participants in total) Note: Participant # is matched to survey response number | 50 male, 38 female | Artisan food producers who use FMs as one of their paths (or only path) to market, are engaged in food production that is not fully mechanised, for which raw ingredients are processed into prepared food products for consumption elsewhere, and who have been in business for a minimum of three years (considered to have overcome their liability of newness). | Average duration of face-to-face survey and informal conversations, 27 min. Conversations were transcribed verbatim where possible, sometimes during the conversation, while the participant was serving customers or directly after the encounter, 33,900 words. |

| Semi-structured interviews (pseudonym) | |||

| Kathy, Interview 1 | Female | Manages a public urban famers’ market that she founded in 1996; also sells her own grown vegetables at two markets. | 50 min interview, 5629 words |

| Mark, Interview 3 | Male | Manager and support officer for incubator kitchen (government initiative for food ventures) and also operates as a food safety consultant. | 20 min interview, 1991 words |

| Nancy, Interview 4 | Female | Enterprise support officer (urban). | 60 min interview, 4797 words |

| Tracy, Interview 6 | Female | FM consultant for Bord Bia (Irish State Food Board); also sells meat produce from the family farm at one FM (outside the region under research). | 50 min interview, 5619 words |

| Brian, Interview 7 | Male | Food business consultant since 2001. | 40 min interview, 4713 words |

| Mary, Interview 8 | Female | Enterprise support officer (rural). | 40 min interview, 5544 words |

| Tom, Interview 9 | Male | Specialised market traders’ insurance broker for 40 years. | 60 min interview, 3036 words |

| Frank, Interview 10 | Male | FM manager and retired trader (rural markets). | 100 min interview, 6611 words |

| ‘Master Artisan’ interviews (pseudonym and matched to survey response number) | |||

| Rolf, Interview 2, #46 | Male | Artisan fish smoker, 40 years trading at FM, original trader in three FMs. | 100 min interview, 9989 words |

| Dan, Interview 5, #52 | Male | Artisan baker, 30 years trading at FMs, original trader in two markets. | 90 min interview, 7359 words |

| Audio-recorded informal conversations (pseudonym and matched to survey response number) | |||

| Maria, #83 | Female | Condiments (horticulturist) | 5 min, 403 words |

| Martin, #79 | Male | Dairy (cheese producer) | 30 min, 2156 words |

| Willian, #100 | Male | Beverages (farmer) | 20 min, 2002 words |

| Olive, #69 | Female | Condiment producer | 5 min, 613 words |

| Marcus, #57 | Male | Condiment producer | 30 min, 2123 words |

References

- Tencati, A.; Zsolnai, L. Collaborative enterprise and sustainability: The case of Slow Food. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 3, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, H. Food and agricultural systems for the future: Science, emancipation and human flourishing. J. Crit. Realism 2015, 14, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, S. The case for studying non-market food systems. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzębowski, S.; Bourlakis, M.; Bezat-Jarzębowska, A. Short food supply chains (SFSC) as local and sustainable systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO). Short Food Supply Chain for Promoting Local Food on Local Markets. 2020. Available online: https://tii.unido.org/sites/default/files/publications/SHORT%20FOOD%20SUPPLY%20CHAINS.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- La Trobe, H.L.; Acott, T.G. Localising the global food system. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2000, 7, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willet, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermuelen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Sustainability. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy: For a fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/system/files/2020-05/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Farrell, M.; Murtagh, A.; Weir, L.; Conway, S.F.; McDonagh, J.; Mahon, M. Irish organics, innovation and farm collaboration: A pathway to farm viability and generational renewal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. COVID-19 and the Role of Local Food Production in Building More Resilient Local Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Liang, Y.; Bai, Y. Mapping the intellectual structure of short food supply chains research: A bibliometric analysis. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2834–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneck Barbosa, M. Uncovering research streams on agri-food supply chain management: A bibliometric study. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 28, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciarotti, C.; Torregiani, F. The logistics of the short food supply chain: A literature review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R. European and United States Farmers’ Markets: Similarities, Differences and Potential Developments. In Proceedings of the 113th EAAE Seminar “A Resilient European Food Industry and Food Chain in a Challenging World”, Chania, Crete, Greece, 3–6 September 2009; Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/58131/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Danermark, B.; Ekström, M.; Jakobsen, L.; Karlsson, J. Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences; Routledge Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]