“Escape the Corset”: How a Movement in South Korea Became a Fashion Statement through Social Media

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Feminism Reboot in South Korea

2.2. Feminism and Fashion in South Korea

2.3. The #EscapeTheCorset Movement

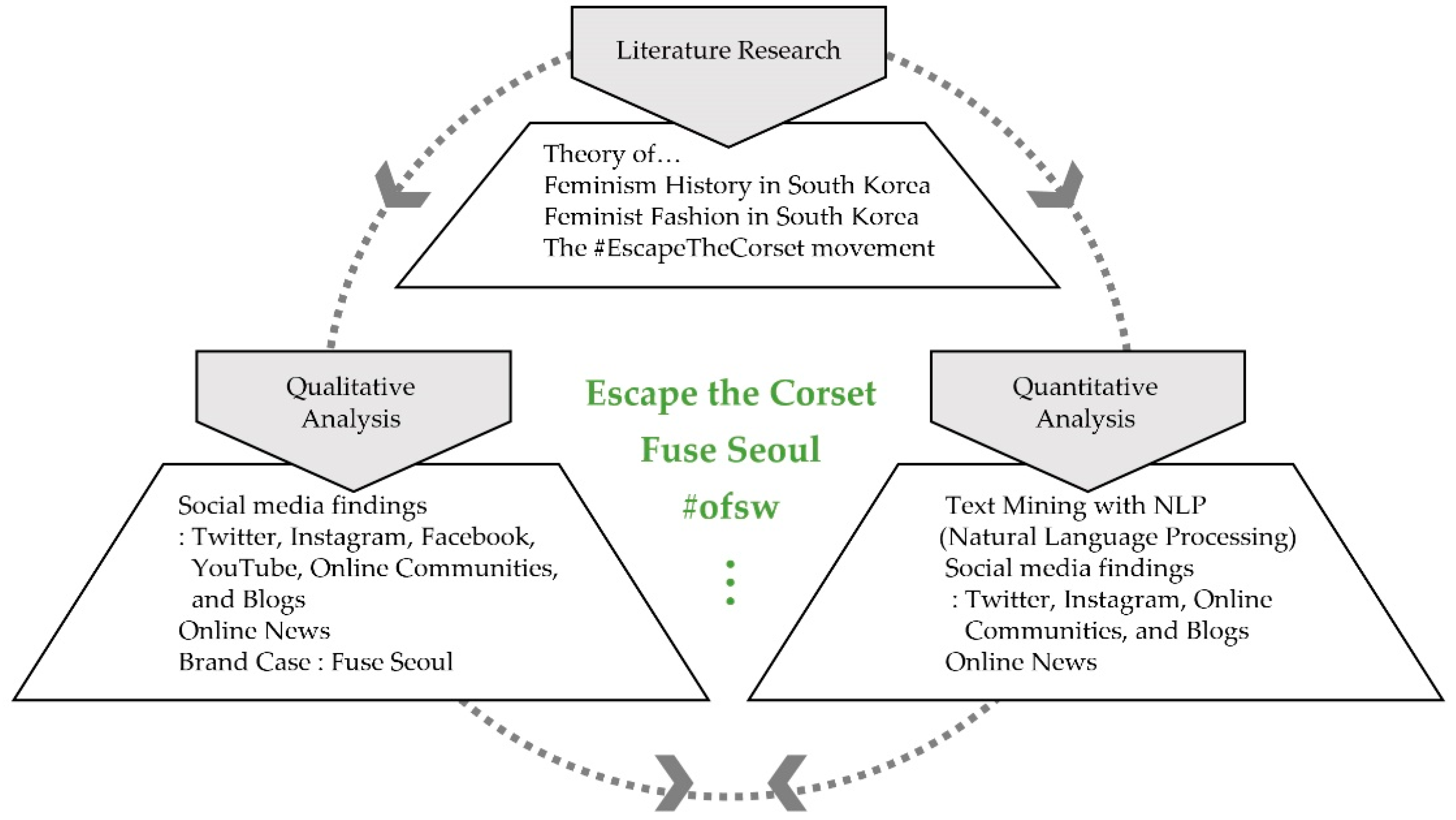

3. Methods

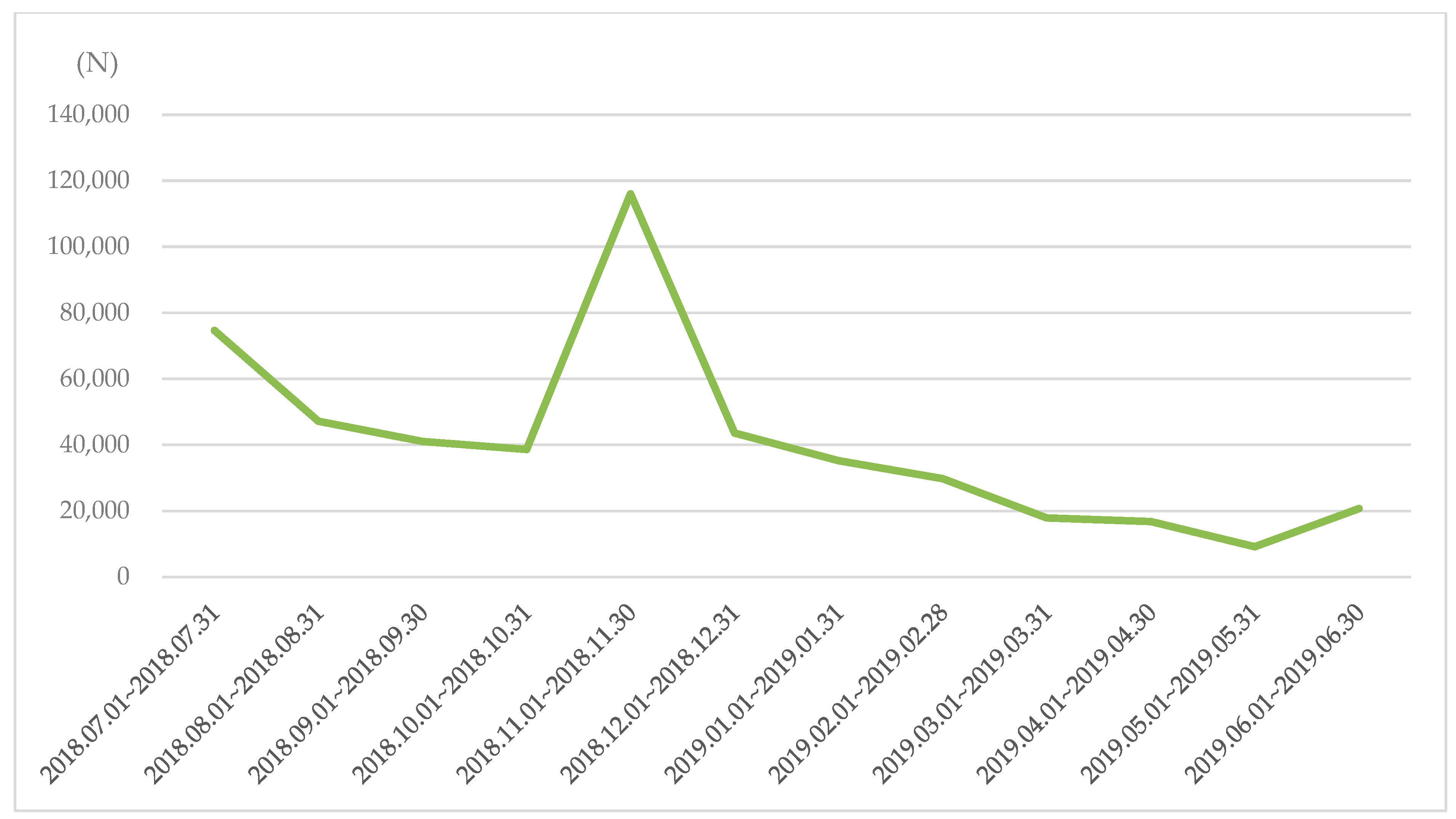

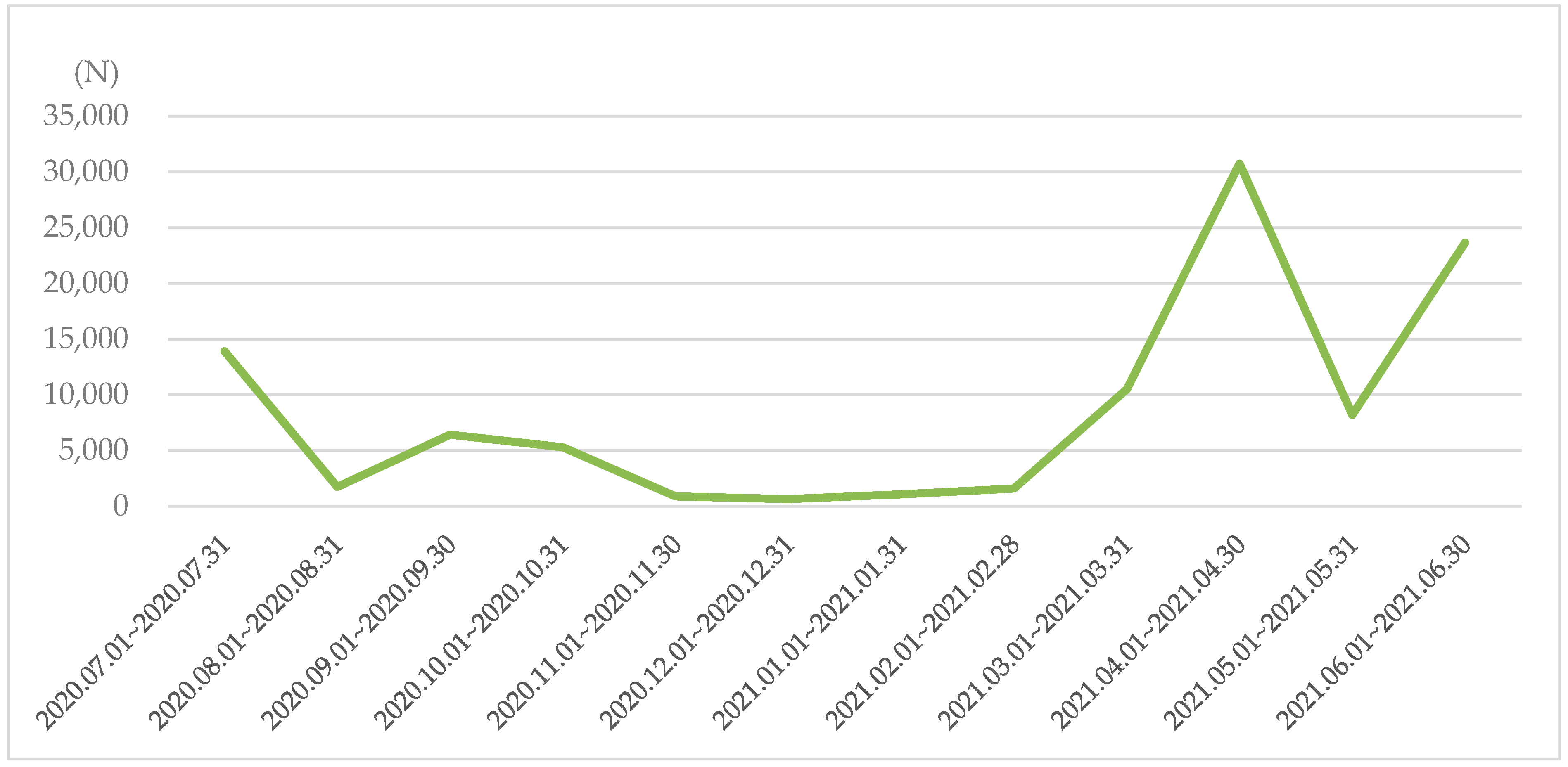

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. On the “Escape the Corset” Fashion

4.2. On the “Escape the Corset” Fashion Brand

4.3. Significance of “Escape the Corset” Fashion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETC | “Escape the corset” |

| ETC-F | “Escape the corset” fashion |

| ETC-M | “Escape the corset” movement |

References

- Kim, E.J. Online feminism as fourth wave: Contemporary feminism’s politics and technology. Korean Fem. Philos. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looft, R. #girlgaze: Photography, fourth wave feminism, and social media advocacy. Continuum 2017, 31, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woman Sense. Escape the Corset Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.smlounge.co.kr/woman/article/41919 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Nelson, J.L. Dress reform and the bloomer. J. Am. Cult. 2000, 23, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, N. The Beauty Myth; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- The Independent. South Korean Women Destroying Makeup in Protest against Stringent Beauty Standards. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/south-korean-women-makeup-destroy-strict-beauty-standards-social-media-a8607396.html (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- CNN. Escape the Corset: How South Koreans are Pushing Back Against Beauty Standards. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/south-korea-escape-the-corset-intl/index.html (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- New York Times. South Korea Loves Plastic Surgery and Makeup. Some Women Want to Change That. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/23/business/south-korea-makeup-plastic-surgery-free-the-corset.html (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- ABC News. Escape the Corset. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-20/south-korean-women-escape-the-corset/11611180?nw=0 (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- TeenVOGUE. An San, South Korean Olympic Archer, Criticized for Her Short Haircut. Available online: https://www.teenvogue.com/story/south-korean-olympic-archer-an-san-criticized-for-short-haircut (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Yun, J.Y. The dynamics of resistant body, insect of the refusal of marriage: The imperceptible body that does not subjugate itself to the regime of male domination. Korean J. Cult. Sociol. 2019, 27, 53–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.S. Feminism’s geologico-economico-affect dynamic: Analysis on the movement of A-corset through the concepts of deterritorialization-work-affect-material. J. Korean Philos. Soc. 2019, 150, 59–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.R. The Movement of ‘Tal-Corsets’ (taking off all corsets), #getreadywithme: Popular feminism in the digital economy. J. Korean Women’s Stud. 2019, 35, 43–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.J. Analysis of changes in Korean female consumers’ interest in beauty products due to the spread of the Escape the Corset Movement. In Proceedings of the KMIS International Conference 2019, Gyeongju, Korea, 25 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, P.E. Feminist ecological economics and sustainability. J. Bioecon. 2007, 9, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.; Murray, A. Sustainability as a lens to explore gender equality: A missed opportunity for responsible management. In Integrating Gender Equality into Business and Management Education; Flynn, P.M., Haynes, K., Kilgour, M.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Do You Know All 17 SDGs? Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Wu, S.R.; Shirkey, G.; Celik, I.; Shao, C.; Chen, J. A Review on the adoption of AI, BC, and IoT in sustainability research. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, D. Sustainability, feminist visions, and the utopian tradition. J. Plan. Lit. 1995, 9, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyunanda, V.F.; Palacios Ramírez, J.; López-Martínez, G.; Meseguer-Sánchez, V. State ibuism and women’s empowerment in Indonesia: Governmentality and political subjectification of Chinese Benteng women. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J. En-gendering notions of leadership for sustainability. Gend. Work. Organ. 2011, 18, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jia, Z.; Yan, S. Does gender matter? The relationship comparison of strategic leadership on organizational ambidextrous behavior between male and female CEOs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G. Revolutionary Feminism: The Mind and Career of Mary Wollstonecraft; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge Dictionary. Feminism. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/feminism (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Jeong, J.W.; Lee, E.A. Gender training to enhance university students’ gender sensitivity—Focusing on <Women’s. Studies> curriculum. Korean J. Gen. Educ. 2018, 12, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Eum, H.J. The history and contemporary meanings of feminist pedagogy: Some analyses on women’s studies as liberal arts in college. J. Korean Women’s Stud. 2019, 35, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.K. Gender policy paradigm and construction of the meaning of the ‘gender perspective’: Theoretical review of the history of policy in South Korea. Korean Assoc. Women’s Stud. 2016, 32, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. MOGEF History. Available online: http://www.mogef.go.kr/eng/am/eng_am_f005.do (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Ryu, Y.K.; Kim, Y.M. An exploratory study on gender conflict perception in Korea: Focused on moderating effect of gender. Korea Soc. Policy Rev. 2019, 26, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica. Feminism. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/feminism (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- The Women’s News. The Little Ball that ‘Megalia’ Fired. Available online: http://www.womennews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=182671 (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Yun, J.Y. Megalian controversy as a revolutionary mirror: Is it possible man-hating? Korean Fem. Philos. 2015, 24, 5–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.M. Late modern misogyny and feminist politics: The case of IlBe, megalia, and Womad. J. Korean Women’s Stud. 2018, 34, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Women’s News. Megalia and Sisters who Led the Closure of SoraNet and Misogyny Public Debate. Available online: http://www.womennews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=94529 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Cho, J.H. The contentiousness of Korean women’s movement: From the perspectives of strategic action fields theory and practice theory. Econ. Soc. 2019, 123, 110–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilda. Counting the Issues of Feminism in 2017. Available online: https://www.ildaro.com/8088 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Na, Y. In 2016, the ‘black protest’ began to make the ‘abolition of abortion crime’ political agenda. Issues Fem. 2017, 17, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.N.; Choi, K.J. History of legal disputes and legislation & amendment of Korean criminal abortion: Focusing on social & political background. J. Democr. Hum. Rights 2020, 20, 169–206. [Google Scholar]

- MBN. Hyehwa Station is Crowded with Protest against Hongdae Molka Biased Investigation. “Only Women can Attend”. Available online: https://www.mbn.co.kr/news/society/3535843 (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Hankyoreh. How did the Anger of ‘Inconvenient Courage’ Change Korean Society. Available online: https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/876251.html (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Sisa Journal. Feminism has Degenerated? "The Mirroring Expiration Date Ends”.. Available online: http://www.sisajournal.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=176506 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- JoongAng Ilbo. [Graphictelling] ‘Illegal Shooting’ Happens 16 Cases Per a Day… Half of Perpetrators are ‘Acquaintances’. Available online: https://news.joins.com/article/23798968 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Bordo, S. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture and the Body; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Erkal, M.M. The cultural history of the corset and gendered body in social and literary landscapes. Eur. J. Lang. Lit. 2017, 3, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leach, W. True Love and Perfect Union the Feminist Reform of Sex and Society; Basic Books, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gattey, C.N. The Bloomer Girls; Coward-McCann: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Money Today. Words Spilled on a T-shirt … Chanel and Dior said. “Feminism is All the Rage”. Available online: https://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2020082109130627212 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Huff Post Korea. There is a Designer who Supported #METOO Movement at Seoul Fashion Week. Available online: https://www.huffingtonpost.kr/entry/missgee-collection_kr_5ab8a4eae4b0decad04b8048 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Noh, H.K. Ugly rights in the post-Corset era. Lit. Crit. Today 2018, 111, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.Y. Escape-the-corset. J. Fem. Theor. Pract. 2019, 41, 138–150. [Google Scholar]

- Femiwiki. Out of the Corset. Available online: https://fmwk.page.link/Hw3N (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Kyunghyang Shinmun. I Refuse Long Hair and Make up Vol. 1020. Women’s Press ‘#EscapetheCorset’ movement. Available online: https://www.khan.co.kr/feature_story/article/201805310600015 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Hankyoreh. 60,000 People gathered at the third Hyehwa Station protest ‘denounce the biased investigation of illegal shooting’. Available online: https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/852321.html (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Newsis. Marching on The Young Femi... “Feminism Is Survival Skills, Escape the Corset Is Liberation”. Available online: https://mobile.newsis.com/view.html?ar_id=NISX20180622_0000343932 (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- LinaBae YouTube. I’m Not Pretty [Video]. Available online: https://youtu.be/Zq51xKG-hyU (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- New South, 1. ‘Escape the Corset Generation’ A Woman in Her 20s bought a Car Instead of Doing Make-Up and Cosmetic Surgery. Available online: https://www.news1.kr/articles/3715860 (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- The Guardian. Escape the Corset: South Korean Women Rebel against Strict Beauty Standards. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/26/escape-the-corset-south-korean-women-rebel-against-strict-beauty-standards (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- BBC News. Why Women in South Korea are Cutting ‘the Corset’. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46478449 (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- NPR. South Korean Women “Escape the Corset” and Reject their Country’s Beauty Ideals. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/05/06/703749983 (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Yun, J.S.; Yunkim, J.Y. Declaration of Tal-Corset; April Books: Goyang, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.K. Escape the Corset: The Coming Imagination; Hani Book: Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wilding, F. Where is feminism in cyberfeminism? N. Paradoxa 1998, 2, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, P.; Gómez, N.R.; Roa, A.F.; Whitson, R. Reviving feminism through social media: From the classroom to online and offline public spaces. Gend. Educ. 2020, 32, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, E.; Fisher, J. Tweeting back while shouting back: Social media and feminist activism. Fem. Psychol. 2018, 28, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braudel, F. The Structures of Everyday Life: The Limits of the Possible; Collins: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle, J. The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Social Theory; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, A. Cut the Protein Hijab and Take off the Bra…The Reason why They Took off Their Jackets. Available online: https://www.donga.com/news/Society/article/all/20180608/90466343/1 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- BBC News Korea. Escape the Corset: Bullying without Makeup… Teenage Women Shouting Escape the Corset. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/korean/news-44329328 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- The Women’s News. No Volume-Up Bra and Bralette, Boxers Instead of Triangular Panties. Available online: http://www.womennews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=183975 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Ssunews. Tighten Women with ‘Beauty’. Available online: http://www.ssunews.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=6518 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- The Women’s News. I Threw Away My Bra Today. Available online: http://www.womennews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=143809 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Kang, J.H.; Geum, K.S. A study on the feminism in contemporary fashion design. J. Korean Soc. Costume 1996, 30, 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- KTNews. Kim Soo-Jung, CEO of Fuse Seoul—“Is There Any Women’s Clothes That Are as Comfortable as Men’s Clothes?”. Available online: https://www.ktnews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=116032 (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Hankook Ilbo. “Let Me Tell You the Truth about Women’s Clothing”. Unusual YouTube Goes Viral. Available online: https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201907290958062368 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Femiwiki. Escape the Corset. Available online: https://fmwk.page.link/5AwR (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Koreabamboo Facebook. Post#41024. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/koreabamboo/posts/929813513888629 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Merriam-Webster. Anti-Fashionable. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anti-fashionable (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Im, S.Y.; Ha, J.S. A Study on the Specificity of Anti-Fashion in the 21st Century—Focused on Articles from the New York Times from 2000 to 2020. Korean Soc. Fash. Des. 2021, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ranking | July 2018–June 2019 | July 2019–June 2020 | July 2020–June 2021 | July 2021–June 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | corset | female | corset | female |

| 2 | female | corset | female | corset |

| 3 | movement | movement | movement | woman |

| 4 | Tal-Co | woman | woman | movement |

| 5 | woman | makeup | feminism | society |

| 6 | man | Tal-Co | Tal-Co | notion |

| 7 | feminism | feminism | society | man |

| 8 | society | clothes | clothes | Tal-Co |

| 9 | male | English | default | diary |

| 10 | makeup | German | man | the middle class |

| Ranking | July 2018–June 2019 | July 2019–June 2020 | July 2020–June 2021 | July 2021–June 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ridicule | nasty | comfortable(+) | positive(+) |

| 2 | curse | good(+) | good(+) | disabled |

| 3 | violence | beautiful(+) | misogyny | hate |

| 4 | misogyny | detest | pretty(+) | curse |

| 5 | swear word | hate | support(+) | nondescript |

| 6 | pretty(+) | beauty(+) | great(+) | ridicule |

| 7 | logical(+) | human(+) | refuse | pretty(+) |

| 8 | chuckle(+) | anger | ridicule | not familiar |

| 9 | recommend(+) | noxious | convenient(+) | misogyny |

| 10 | inexpensive(+) | support(+) | wish(+) | comfortable(+) |

| Ranking | July 2018–June 2019 | July 2019–June 2020 | July 2020–June 2021 | July 2021–June 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seoul | Seoul | Seoul | Seoul |

| 2 | clothes | clothes | clothes | clothes |

| 3 | shopping mall | trousers | trousers | size |

| 4 | trousers | shopping mall | drawers | desert |

| 5 | size | refrigerator | refrigerator pants | lamb |

| 6 | shirt | refrigerator pants | refrigerator | trousers |

| 7 | model | size | Hanbok | coin |

| 8 | woman | suit | size | TV |

| 9 | corset | shirt | modernized Hanbok | prime cost |

| 10 | Hawaiian shirt | womenswear | desert | hooded t-shirt |

| Ranking | July 2018–June 2019 | July 2019–June 2020 | July 2020–June 2021 | July 2021–June 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | improve(+) | nice(+) | good(+) | new(+) |

| 2 | win(+) | comfortable(+) | attach | new model(+) |

| 3 | pleasure(+) | attach | durable(+) | wish(+) |

| 4 | doubt | like(+) | comfortable(+) | possible |

| 5 | good(+) | look good(+) | fresh(+) | good(+) |

| 6 | do it well(+) | worth(+) | insufficiently-dressed | the best(+) |

| 7 | work well(+) | the best(+) | sale(+) | highly recommended(+) |

| 8 | nice(+) | good(+) | expectation(+) | discrimination |

| 9 | recommend(+) | cheer(+) | thankful(+) | comfortable(+) |

| 10 | perfect(+) | trust(+) | curse | thankful(+) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, Y.; Lee, S. “Escape the Corset”: How a Movement in South Korea Became a Fashion Statement through Social Media. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811609

Shin Y, Lee S. “Escape the Corset”: How a Movement in South Korea Became a Fashion Statement through Social Media. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811609

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Yeongyo, and Selee Lee. 2022. "“Escape the Corset”: How a Movement in South Korea Became a Fashion Statement through Social Media" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811609

APA StyleShin, Y., & Lee, S. (2022). “Escape the Corset”: How a Movement in South Korea Became a Fashion Statement through Social Media. Sustainability, 14(18), 11609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811609